Abstract

Objective

To examine the proportion of healthcare visits are delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants versus physicians and how this has changed over time and by clinical setting, diagnosis, and patient demographics.

Design

Cross-sectional time series study.

Setting

National data from the traditional Medicare insurance program in the USA.

Participants

Of people using Medicare (ie, those older than 65 years, permanently disabled, and people with end stage renal disease), a 20% random sample was taken.

Main outcome measures

The proportion of physician, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant visits in the outpatient and skilled nursing facility settings delivered by physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, and how this proportion varies by type of visit and diagnosis.

Results

From 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2019, 276 million visits were included in the sample. The proportion of all visits delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in a year increased from 14.0% (95% confidence interval 14.0% to 14.0%) to 25.6% (25.6% to 25.6%). In 2019, the proportion of visits delivered by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant varied across conditions, ranging from 13.2% for eye disorders and 20.4% for hypertension to 36.7% for anxiety disorders and 41.5% for respiratory infections. Among all patients with at least one visit in 2019, 41.9% had one or more nurse practitioner or physician assistant visits. Compared with patients who had no visits from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, the likelihood of receiving any care was greatest among patients who were lower income (2.9% greater), rural residents (19.7%), and disabled (5.6%).

Conclusion

The proportion of visits delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the USA is increasing rapidly and now accounts for a quarter of all healthcare visits.

Introduction

The number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants is increasing in the United States of America. From 2019 to 2031, the Bureau of Labour Statistics estimates that the number of nurse practitioners will increase from 200 000 to 359 000 (80 percent growth), whereas the number of physician assistants will increase from 120 000 to 178 000 (48 percent growth).1 However, to date, quantifying the proportion of care and the type of care provided by nurse practitioners and physician assistants has been hampered by the use of indirect billing (also called incident-to or shared visit billing). With indirect billing, the nurse practitioner or physician assistant provides most of the care for a patient but the bill for the service is submitted under a supervising physician.2 A novel method, published in 2022, described how to identify indirect billing visits and estimated that nationally between 2010 and 2018, 44% of all nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits in the US were billed indirectly.3 Therefore, prior research that only examines the visits directly billed by an nurse practitioner or physician assistant substantially underestimates their involvement in the US health care system and conversely overestimates the involvement of physicians.3 4

To better characterise the involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the US health care system, we identified indirect billing in traditional Medicare claims to estimate the proportion of visits delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants and how this varied by clinical setting and diagnosis and by patient demographics.3 We also characterize which patients are more likely to receive care from an nurse practitioner or physician assistant.

Methods

Healthcare staff and their role in visits with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are employed worldwide, albeit in lower rates compared with the US (appendix methods).5 6 In the US, nurse practitioners and physician assistants are required to earn a graduate degree, complete a specified schedule of clinical training, and acquire appropriate certifications and licenses.7 Each state has its own regulations dictating their practice.8 9 Unlike scope of practice laws for physician assistants, which are generally consistent across states and require physician assistants to work with a physician,9 scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners varies widely across states. The American Association of Nurse Practitioners has characterized the scope of practice laws for nurse practitioner for each state as either full, reduced, or restricted.8 In a full scope of practice state, a nurse practitioner can practice fully independently and may have their own clinic.

The relative role of the nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and physician will vary in individual visits. In many visits involving a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, the physician does not see the patient and is not involved in the diagnosis and management of the patient.10 11 In other visits, the supervising physician may provide advice to the nurse practitioner or physician assistant at the time of the visit but does not physically see the patient. Physicians may also physically see the patient and have a more substantive role, particularly for visits in nursing facilities. Substantial ambiguity and controversy surrounds the billing guidelines and what is required when a visit is billed indirectly by a physician.12

Consistent with new guidelines by the US federal government for a form of indirect billing,13 when a visit is labelled as a nurse practitioner or physician assistant visit, we assume the visit is assigned to the clinician who spent the most time in history taking, physical exam, decision making, and management.

Data source

We used a 20% random sample of traditional Medicare claims data from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2019 (see appendix for detail on data source). Medicare is the health insurer for people older than 65 years, permanently disabled, and people with end stage renal disease. Medicare accounts for roughly 20% of the US population and 23% of health care spending.14 Depending on the year in our cohort, traditional Medicare includes 61% to 71% of all people enrolled in Medicare (details in appendix). We excluded data from 2020 forward because we were concerned that care delivery changes related to the pandemic could distract from our key goal, which was to investigate the involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in care delivery.

We identified all visits, both telemedicine and in-person, in the settings of outpatients (eg, office, hospital outpatient, retail clinics, and urgent care) or nursing facilities (eg, skilled nursing facility, hospice, and assisted living facility); we excluded visits in the inpatient and emergency department. Details on the codes used to identify and categorize visits and the full list of clinical settings are in the appendix.

Patient, visit, and county characteristics

We characterized patients by age, sex, race and ethnicity, low income (as captured by also being enrolled Medicaid, a public health insurance program that covers many Americans on low incomes), urban or rural residence, and region of the county.

Visits were categorized by diagnosis using the Clinical Classification Software Refined15 system and the primary diagnosis for the visit.16 17 For physician visits, we identified the specialty using the listed specialty (appendix).18 Primary care providers were defined as physicians with a specialty of general internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, or geriatric medicine. We also divided visits into those in the outpatient versus nursing facility settings.

We characterized counties by their 2019 state-level nurse practitioner scope of practice8 and by rurality (defined in appendix).19 20 We hypothesized that states with restricted scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners would have fewer nurse practitioner visits because these nurses are less able to deliver care independently compared with those working in states with full scope of practice laws.21 22 Physicians are in relatively short supply in rural communities,23 therefore, we hypothesized that nurse practitioners and physician assistants would account for a larger proportion of visits in rural areas.

Identifying visits misclassified as physician visits due to indirect billing

Details on how we used prescriptions to identify indirectly billed visits and the validity of this approach are available in a prior publication,3 as well as in the appendix. Briefly, we first identified all visits billed by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or physicians. Secondly, we found visits with an associated prescription. An associated prescription was one written by an nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or physician one day before, on, or one day after the visit. We selected a one day window because this timeline provides more confidence that the prescription was made during the associated visit. If the nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or physician on the prescription and visit were the same, we categorized the visit as billed directly. However, if the clinicians on the visit and the prescription were different, with the prescription written by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant and visit billed by a physician, we considered these situations as potentially indirectly billed. From this group of potentially indirectly billed visits, we eliminated visits where whether the nurse practitioner or physician assistant provided care was unclear and therefore our estimate on the proportion of visits provided by nurse practitioner or physician assistant may be conservative. For example, we excluded visits if more than one prescription was given from different nurse practitioners or physician assistants during the time window because the related visit and prescription were not clear. The full list of exclusions in the appendix.

Extrapolating patterns observed among visits with a prescription to all visits

Our method of identifying visits indirectly billed can only be used for visits with an associated prescription. The second step in the method was to extrapolate patterns observed in visits with a prescription to those without a prescription. To do so, we used an inverse probability weighting procedure.24 For each visit, we estimated the probability (along with the 95% confidence interval) that the visit would have an associated prescription based on clinical setting, condition, patient characteristics, and geography. For visits with an associated prescription, we applied the inverse of that predicted probability as the weight for that visit in our analyses. This method assumed that the rate of indirect billing observed in a given visit with a prescription is the same as the rate of indirect billing observed in a similar visit in terms of setting, condition, patient characteristics, and geography, without a prescription (further explanation of why the weighting is needed and details on the variables used are provided in the appendix).

As a sensitivity analysis, we used a different method of generalizing from visits with an associated prescription to all visits. For each visit with a prescription, we used a regression model where the outcome was whether the visit was indirectly billed, and the predictor variables were the same visit characteristics used that were previously described. For each visit without a prescription, we estimated the likelihood that the billing was indirect using the regression coefficients from this model and the visit characteristics. This sensitivity analysis resulted in similar findings (details on method and comparison of results in the appendix). In both methods, standard errors were adjusted for patient level clustering.

Statistical analyses

For each year, we measured the mean number nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and physician visits (with and without prescription) per patient in the cohort (including those without visits) as well as the proportion of all visits provided by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. We also examined how the proportion varies by type of visit and by condition categories. We focused on the 27 most common condition categories, with each condition accounting for more than 1% of total visits and collectively 76% of all visits in 2019. Standard errors were adjusted for patient level clustering.

Some researchers have hypothesized that more visits are by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in communities with fewer physicians.25 To understand whether there were more nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits per patient in communities with fewer physician visits per patient, we divided zip codes into deciles of the number of physician visits per patient. We used observed physician visits per capita versus physicians working in the community per capita because we believe these values better capture the true supply of physicians. Data for physicians working includes physicians who do not provide care to Medicare patients (eg, military physicians) and do not distinguish between part-time and full-time physicians. To ensure stable estimates, we excluded zip codes with fewer than five people enrolled in our data. We selected the five because this number represented the bottom decile of zip codes in our sample.

To characterize which patients were more likely to receive care from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, we used a multivariable patient-level logistic regression of the likelihood of receiving any care from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (defined as yes or no) among people who received at least one visit in 2019 (table 1). This analysis used the unweighted sample. Our predictors included patient characteristics (defined previously), and nurse practitioner scope of practice laws (defined as either restricted, reduced, or full). We presented average marginal effects, which is the average of predicted changes in fitted values for a one unit change for a given covariate.26 As a sensitivity analysis, we limited our analysis to patients with at least three total visits (physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant visits) to ensure stable estimates. We selected three because this number was the median value in the distribution of total visits (appendix).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with at least one nurse practitioner or physician assistant visit in 2019. Data percentage, unless otherwise specified

| Characteristics | Patients with at least one visit (n=6 806 540) |

Patients with no visit (n=9 443 340) |

Estimated likelihood of at least one visit, percentage point difference (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 41.9 | 58.1 | — |

| Race/ethnicity: | |||

| White | 43.1 | 56.9 | Reference |

| Black | 40.5 | 59.5 | −4.9 (−5.1 to −4.7) |

| Other | 34.7 | 65.3 | −5.8 (−6.2 to −5.5) |

| Asian | 20.3 | 79.7 | −19.0 (−19.3 to −18.7) |

| Hispanic | 38.5 | 61.5 | −5.3 (−5.5 to −5.1) |

| American Indian | 57.7 | 42.3 | 5.3 (4.6 to 6.1) |

| Sex: | |||

| Female | 44.1 | 55.9 | Reference |

| Male | 38.7 | 61.3 | −6.2 (−0.63 to −6.0) |

| Reason for Medicare enrollment: | |||

| Older age | 38.9 | 61.1 | Reference |

| Disabled | 50.9 | 49.1 | 5.6 (5.5 to 5.8) |

| Dual Medicaid enrollment†: | |||

| No | 40.3 | 59.7 | Reference |

| Yes | 47.2 | 52.8 | 2.9 (2.8 to 3.1) |

| Age (years): | |||

| 18-29 | 55.6 | 44.4 | 12.8 (12.0 to 13.5) |

| 30-39 | 56.3 | 43.7 | 12.9 (12.5 to 13.4) |

| 40-49 | 56.5 | 43.5 | 12.6 (9.6 to 10.2) |

| 50-59 | 53.7 | 46.4 | 9.9 (9.6 to 10.2) |

| 60-64 | 50.9 | 49.1 | 7.4 (7.0 to 7.7) |

| 65-79 | 40.9 | 59.1 | 3.8 (3.7 to 3.9) |

| 80 and older | 36.9 | 63.1 | Reference |

| Rural: | |||

| Metro (population of >1 million) | 34.0 | 66.0 | Reference |

| Metro (population of 250 000-1 million) | 45.9 | 54.1 | 10.6 (10.5 to 10.7) |

| Non-metro, non-rural | 51.4 | 48.6 | 15.1 (14.9 to 15.2) |

| Rural | 55.9 | 44.1 | 19.7 (19.4 to 20.1) |

| State scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners: | |||

| Restricted | 42.0 | 58.0 | Reference |

| Reduced | 40.8 | 59.2 | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) |

| Full | 42.7 | 57.3 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) |

Only patients with at least one visit in 2019 were included in analysis. To characterize which patients were more likely to receive care from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, we used a multivariable patient level logistic regression of the likelihood of receiving any care from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (defined as yes or no) among those who received at least one visit in 2019. We presented average marginal effects, which is the average of predicted changes in fitted values for a one unit change for a given covariate. CI=confidence interval.

Average estimated marginal effect are adjusted percent differences.

Medicaid is a public health insurance program that covers many Americans on low incomes.

For each physician specialty, we estimated the proportion of all billed visits that were indirectly billed and therefore actually provided by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. We focused on the 20 most common specialties because they accounted for 86% of all specialty visits.

We multiplied all visit and patient counts by five to account for our 20% sample. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question, developing the outcome measures, design, or implementation of the study, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. Our study used already collected de-identified restricted claims data purchased from the US federal government. Harvard Medical School’s institutional review board do not require that patients or members of the public planning are involved when the study was planned or submitted to ethical committees and funding agencies. These data were stored in a secure environment and required authorization to access.

Results

Care delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants

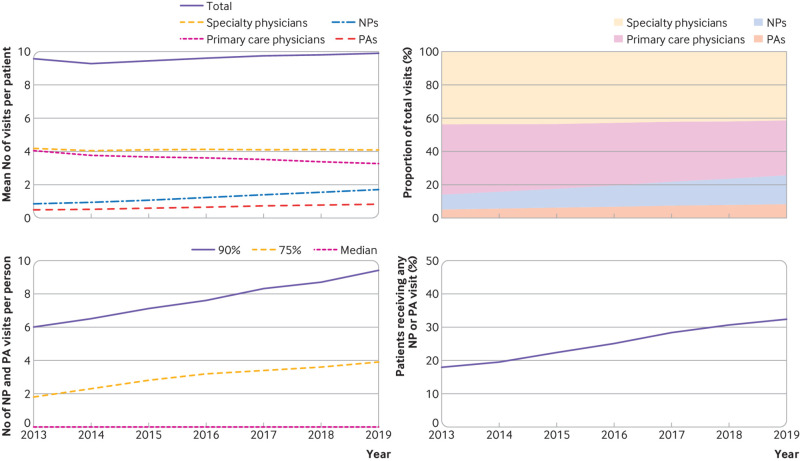

From 2013 to 2019, 275 915 797 visits were recorded in our sample. The mean number of nurse practitioner visits per patient per year increased from 0.9 (standard deviation 3.8) to 1.7 (5.5), an 89% increase, and the mean number of physician assistant visits per patient increased from 0.5 (2.6) to 0.8 (3.3), a 60% increase) (fig 1). The number of visits per patient was skewed and the median number of visits to a nurse practitioner or physician assistant was 0 throughout the study period; the 75th percentile number of nurse practitioner or physician assistant visits per patient per year increased from 1.8 to 3.9 (117% increase) and the 90th percentile increased from increased from 6.0 to 9.4 (57% increase; supplementary table S9). From 2013 to 2019, the total number of patients with any nurse practitioner or physician assistant visit increased from 17.9% to 32.3% (fig 1; table 1).

Fig 1.

Trends in the number of nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) visits per patient, the percentage receiving any NP or PA visit, and fraction of total visits delivered by NPs and PAs, 2013-19. We applied an inverse probability weighting method to the number of visits per patient (appendix). 95% confidence intervals can be found in appendix table S6; estimates for the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range are presented in appendix table S9. We separately measured visits per patient for NPs, PAs, specialty physicians, and primary care physicians. We separately measured the proportion of total visits delivered by NPs and PAs. The denominator was the number of visits in our sample provided by NPs and PAs (both indirectly and directly billed) and physicians (specialty and primary care physicians). The numerator was the number of these visits billed by NPs and PAs (both indirectly and directly billed). We measured the median, 75th, and 90th percentiles of visits per patient for NPs and PAs (appendix table S9). We also measured the percentage of patients receiving any NP or PA visit

By contrast, during this period, the mean number of visits by a primary care physician per patient per year decreased from 4.0 (standard deviation 5.5) to 3.3 (5.1) (18% decrease), whereas mean specialty physician visits per patient per year only slightly decreased from 4.2 (8.3) to 4.1 (7.9) visits (2% decrease). Compared with nurse practitioners and physician assistants, primary care physicians are more likely to provide new patient visits and less likely to provide annual exams (supplementary table S5).

From 2013 to 2019, the proportion of total visits delivered by nurse practitioners in a year increased from 8.9% (95% confidence interval 8.9% to 8.9%) to 17.3% (17.3% to 17.3%), additionally, the proportion delivered by physician assistants increased from 5.1% (5.1% to 5.1%) to 8.4% (8.4% to 8.4%). Together, the proportion of total visits delivered by either a nurse practitioner or a physician assistant increased from 14.0% (14.0% to 14.0%) to 25.6% (25.6% to 25.6%). The proportion of total weighted visits delivered by primary care physicians decreased from 42.4% (42.4% to 42.4%) to 33.0% (33.0% to 33.1%) and the percentage delivered by specialty physicians decreased slightly from 43.7% (43.7% to 43.7%) to 41.3% (41.3% to 41.3%).

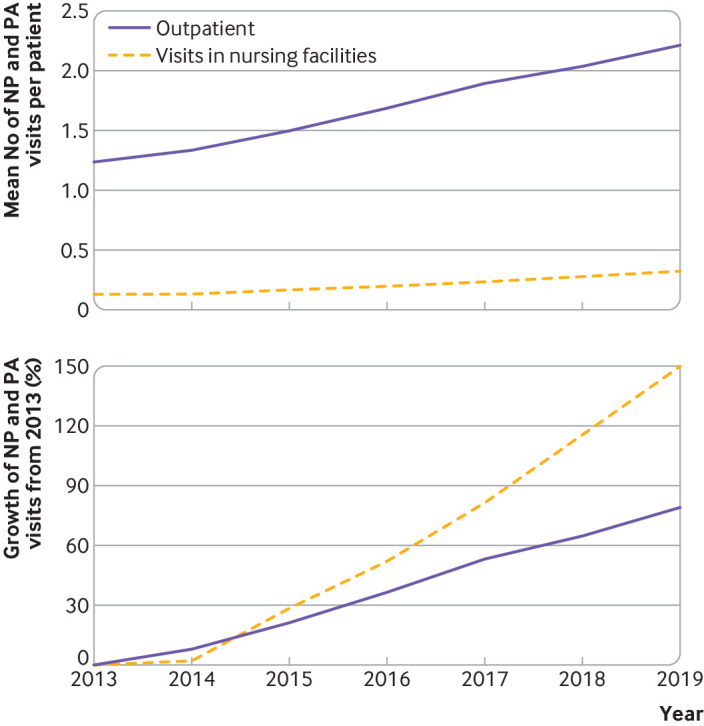

From 2013 to 2019, the mean number of annual visits per patient delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants increased from 1.2 (standard deviation 4.0) to 2.2 (4.7) (83% growth from 2013 to 2019) in the outpatient setting, and from 0.1 (2.1) to 0.3 (4.3) (200% growth) in nursing facilities (fig 2). Again, the number of nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits per patient at these care sites was skewed and the median number of visits to a nurse practitioner and physician assistant was 0 throughout the study period (supplementary table S9).

Fig 2.

Trends in the mean number of nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) visits by setting from 2013 to 2019 and relative growth in NP and PA visits from 2013 by setting. We focused on evaluation and management visits as defined using the Restructured Berenson-Egger Type of Service codes. We only included visits in outpatient and nursing facility settings. We applied an inverse probability weighting method to the number of visits per patient (appendix). 95% confidence intervals can be found in appendix table S7; estimates for the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range are presented in appendix table S9

Characteristics of patients who receive care

Among the 16 249 880 patients with at least one visit in 2019, 6 806 540 patients (42%) had at least one nurse practitioner or physician assistant visit and 1 688 930 (10%) only had visits with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (table 1). We observed a lower proportion of patients having at least one visit from nurse practitioners and physician assistants among patients who were black relative to white (−4.9% (95% confidence interval −5.1% to −4.7%)) and patients who were male relative to female (−6.2% (−6.3% to −6.0%)). Conversely, we observed higher use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants among patients who were disabled (5.6% (5.5% to 5.8%)), had a lower income (2.9% (2.8% to 3.1%)), and lived in a rural area (19.7% (19.4% to 20.1%)).

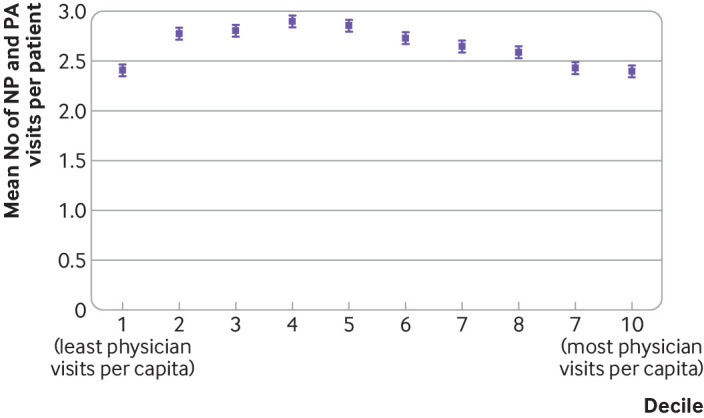

Visits per patient by nurse practitioners and physician assistants versus physicians

Across the zip code deciles of physician visits per patient in 2019, no consistent relation was clear between the number of nurse practitioner or physician assistant visits per patient and the number of physician visits per patient (fig 3). A possible positive association in the lower deciles and a negative relation in zip codes with more physician visits per patient was noted. This negative association in higher deciles was possibly more evident in states with full scope of practice laws (supplementary figure S3).

Fig 3.

Association of the mean number of nurse practitioner (NP)/physician assistant (PA) visits and physician visits per patient in 2019 across geographical areas in the USA. To ensure stable estimates, we eliminated zip codes with fewer than five people enrolled in Medicare. We selected five because this number represented the bottom 10 percentile of zip codes for the number of people enrolled in traditional Medicare in the 20% Medicare sample. We apply an inverse probability weighting method to the number of visits per patient (see appendix for details). We present median and the interquartile range for the number of NP and PA visits per patient; estimates for the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range are presented in appendix table S10. The unit of analysis is zip code. We divided all zip codes in the US in into deciles of physician visit per capita, with each decile containing approximately 3295 zip codes. Physician visits per capita for each decile (range does not include the upper bound): 1 (0-3.8); 2 (3.8-4.7); 3 (4.7-5.4); 4 (5.4-5.9); 5 (5.9-6.5); 6 (6.5-7.0); 7 (7.0-7.6); 8 (7.6-8.4); 9 (8.4-9.6); 10 (9.6-62.9)

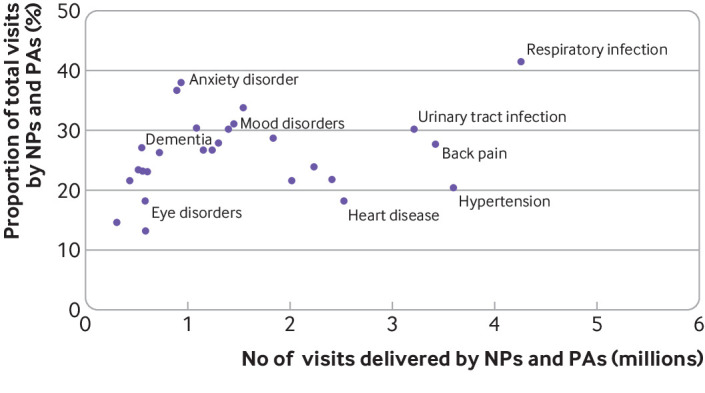

Variation in nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits by condition categories

Among the 27 most common condition categories, nurse practitioners and physician assistants provided the largest proportion of visits for respiratory infections (41.5%, 4.3 million visits) and anxiety disorders (36.7%; 0.89 million visits) (fig 4). Nurse practitioners and physician assistants provided the smallest fraction of visits for heart disease (18.2%; 2.5 million visits) and eye disorders (13.2%, 0.59 million visits).

Fig 4.

Proportion of total visits delivered by nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) for each condition by percentage of total visits for each condition in 2019. We focused on the 27 most common conditions as each condition accounted for at least 1% of total visits and collectively about 76% of total visits in 2019. All 27 conditions and the proportion delivered by NP and PAs are in the appendix

Proportion of physician visits that are billed indirectly

Visits that are billed indirectly are those provided by nurse practitioners and physician assistants but billed under a physician. From 2013 to 2019, the proportion of billed physician visits where the primary clinician was a nurse practitioner or physician assistant increased from 4.8% to 6.9% (supplementary table S2). In 2019, specialties varied widely in the proportion of visited billed indirectly by physician specialty, ranging from 19.2% in general surgery, 15.5% in psychiatry, 13.3% in urology to 9.1% in gastroenterology, 7.7% in dermatology, 5.7% in ophthalmology, and 4.3% in pain management (supplementary table S3).

Discussion

Principal findings

From 2013 to 2019, the proportion of all visits delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants to people enrolled on the traditional Medicare program increased from 14.0% to 25.6%. In 2019, the proportion of total visits delivered by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant varied substantially, ranging from 13.2% for eye disorders to 41.5% for respiratory infections. Consistent with prior literature,27 28 concurrent with the growth in nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits, primary care physician visits per patient per year decreased by 18%. Among all patients who had at least one visit, 42% had at least one visit with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant and the likelihood of receiving any care from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant was greatest among patients with lower incomes, residing in rural areas, and who are disabled.

Comparison with other studies

Our estimate of 25.6% visits provided by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant is consistent with a prior study examining primary care visits in a single electronic health record system, which found 27.2% were provided via a nurse practitioner or physician assistant.4 Our study extends this work by looking at visits on a national scale, across all clinical specialties, and by clinical condition.

These results illustrate the rapidly growing involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the US health care system. The proportion of care provided by nurse practitioners and physician assistants will likely only increase over time because substantially more new nurse practitioners and physician assistants are entering the workforce compared with physicians.1 Although Americans have historically seen a physician as their usual clinician, increasingly that usual clinician will now be a nurse practitioner or physician assistant.29 One survey indicated that 54% of Americans had difficulty differentiating between the role of the nurse practitioner and the physician with varying opinions about differences in qualifications.29 This confusion may increase in the future given the shift of some nurse practitioner education programs to doctor of nursing practice degrees,30 which means that some nurse practitioners may also be called doctors.

However, our results do not support the idea that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are simply replacing physicians in a one-to-one fashion. Rather, clinicians are complementing each other with nurse practitioners and physician assistants having a greater focus on some types of visits, possibly where their training and expertise is best suited. Across conditions, we observe substantial differences in the involvement of nurse practitioner and physician assistants with higher involvement in low acuity acute problems (eg, respiratory infections and urinary tract infections) and mental illness, and a lesser role for heart disease and eye disorders. Compared with nurse practitioners and physician assistants, primary care physicians are more likely to provide new patient visits and less likely to provide annual exams. Surprisingly, we found that in areas of the US with fewer physician visits per capita, fewer numbers of nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits were recorded. We hypothesize that this finding reflects a shift to team based care and that nurse practitioners and physician assistants often practice alongside physicians. Our findings echo prior work in which substantial variation has been reported in the role of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in multidisciplinary teams across patient counseling, educational services, and the provision of primary care.31 32 33 34 A large body of research has directly compared nurse practitioners and physicians on the quality of care and spending. Although exceptions exist,35 in general, many studies have found similar quality and spending.36 37 38 39 40 41 42 One criticism of this published literature is that these studies make direct comparisons of clinicians with different training. We believe more research is needed to understand how nurse practitioners and physician assistants are integrated into practice, and if configurations are optimal in terms of the mix of clinicians on the quality and efficiency of care delivered.36 37 38 39 40 41 42

Our results also show that younger patients who are more likely to be disabled or have lower income and those who live in rural areas are more likely to receive care from a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are also increasingly involved in care for older patients in nursing facilities. Taken together, these results suggest that nurse practitioners and physician assistants provide more care to underserved communities in the US.

Among industrialized countries, the US is in an outlier in that it has fewer physicians per capita.6 7 Our results highlight that the US has addressed this relative shortage through a growing reliance on nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants now work in many other countries (appendix),6 7 and the trends we observe in the US could inform other countries because they consider how to address their own clinician shortages.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. Firstly, we cannot directly link a prescription to a given visit. We assumed that a prescription that was filled within a one day window around a visit was associated with that visit. However, we acknowledge that some misclassification is possible where the nurse practitioner or physician assistant writes prescriptions on behalf of the physician who provided care and where physicians write prescriptions on behalf of the nurse practitioner or physician assistant who provided care. Secondly, we limited our analysis to people who were enrolled in the traditional Medicare program with Part D coverage (roughly 47% of all people enrolled in Medicare) and therefore, may not be generalizable to other populations in the US health care system including those enrolled in Medicaid, commercial insurance, and Medicare Advantage programs. The latter may be particularly important, because during the study period enrollment in Medicare Advantage increased significantly.43 Third, we focused only on visits delivered by physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants and did not include visits from many other clinicians, such as social workers and psychologists. Fourth, our method of identifying indirect billing visits necessarily focuses on visits with an associated prescription, and we then extrapolate the patterns observed in those visits to all visits through an inverse probability weighting procedure. Neither our method of linking prescriptions to visits nor our weighting procedure is perfect, and this may bias our findings. For example, if nurse practitioners and physician assistants prescribed at higher rates than physicians, our estimates for rates of nurse practitioner and physician assistant visits would be too high. Conversely, if physicians prescribed at higher rates than nurse practitioners and physician assistants, our estimates would be too low. We do not know the direction or magnitude of such a bias. Fifth, a limitation of administrative claims is the nurse practitioner and physician assistant specialisation is not generally specified and therefore we cannot describe the relative importance of different types of nurse practitioner and physician assistant training (for example, those with expertise in mental health, primary care, or obstetric care). Sixth, we used the primary diagnosis on the visit to categorize visits, but this diagnosis may not always accurately reflect the reason for the visit.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, we believe our results provide the best available estimate of the involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the US health care system. In summary, we found that from 2013 to 2019, the fraction of all traditional Medicare visits delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants increased from 14.0% to 25.6%. Our results highlight the rapidly growing involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the US. Future research is needed to understand the implications of this growth on the quality of care that Americans receive.

What is already known on this topic?

An increasing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants provide care in the US and many other countries, but little work has characterized the care that they provide

Quantifying the care provided by nurse practitioners and physician assistants has been hampered in the US by the use of indirect billing, where the bill is submitted under a supervising physician

Research that only examined visits directly billed by a nurse practitioners or physician assistants substantially underestimates their involvement in the US health care system and conversely overestimates the involvement of physicians

What this study adds?

From 2013 to 2019, the proportion of all traditional healthcare visits delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants increased from 14.0% to 25.6%

For some clinical conditions, such as respiratory infections, nurse practitioners and physician assistants provide a larger proportion of healthcare visits

Our results highlight the rapidly growing involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the US

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Shyu for contributing to manuscript preparation efforts.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Online appendix

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study; management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. AM supervised the study and is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This project was supported by the National Institute on Ageing of the National Institutes of Health (K23 AG058806-01) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH112829, T32MH019733). This work does not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the US Government, or any other organisation with which the authors are affiliated. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

AM affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies are disclosed.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The results of this work will be disseminated to the public through institutional press release, ensuing news articles, and an opinion piece authored by the study’s authors that describe the study’s findings for the public.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Harvard Medical School.

Data availability statement

No additional data available.

References

- 1.Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook. https://www.bls.gov/ooh. Accessed 1 February 2023.

- 2. Medpac . Medicare and the health care delivery system. 2019; 503 https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec.pdf

- 3. Patel SY, Huskamp HA, Frakt A, et al. Frequency of indirect billing of nurse practitioner and physician assistant office visits. Health Aff 2022;41:805-13. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neprash HT, Smith LB, Sheridan B, Hempstead K, Kozhimannil KB. Practice patterns of physicians and nurse practitioners in primary care. Med Care 2020;58:934-41. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maier CB, Barnes H, Aiken LH, Busse R. Descriptive, cross-country analysis of the nurse practitioner workforce in six countries: size, growth, physician substitution potential. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011901. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hooker RS., Berkowitz O. A global census of physician assistants and physician associates. JAAPA;2020;. 33:43-45. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000721668.29693.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deshaies S. Nurse practioner vs. physician assistant: what’s the difference? Nurse Journal. Published 22 May 2022. https://nursejournal.org/resources/np-vs-physician-assistant

- 8. Phillips SJ. 30th Annual APRN Legislative Update: Improving access to healthcare one state at a time. Nurse Pract 2018;43:27-54. 10.1097/01.NPR.0000527569.36428.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American Medical Association Advocacy Resource Center . Physician assistant scope of practice; 13 Jan 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/arc-public/state-law-physician-assistant-scope-practice.pdf

- 10.Maguire P. Split visit billing rules for physicians and NPs/PAs. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/split-visit-billing-new-rules-physicians-nps-pas/. Last updated January 2022. Accessed 1 February 2023.

- 11.Volpe KD. Medicare indirect billing: NPs and PAs speak out. Split visit billing rules for physicians and NPs/PAs. https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/home/topics/practice-management-information-center/medicare-indirect-billing-nps-pas-speak-out/. Last updated 8 September 2022. Accessed 1 February 2023.

- 12. Glaser DM. Making sense of shared visits. RAC Monitor. Published 26 May 2021. https://racmonitor.medlearn.com/making-sense-of-shared-visits/

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. 2023 Medicare physician fee schedule fine rule. Accessed 1 February 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2023-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule.

- 14.Congressional Research Service. US Health Care Coverage and Spending . 2023. Accessed 15 February 2023. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10830.pdf

- 15. Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR). [Computer software] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Bajorunaite R, Sparapani RA, Freeman JL. An algorithm for the use of Medicare claims data to identify women with incident breast cancer. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1733-49. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rannikmäe K, Ngoh K, Bush K, et al. Accuracy of identifying incident stroke cases from linked health care data in UK Biobank. Neurology 2020;95:e697-707. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CMS Specialty Codes/Healthcare Provider Taxonomy Crosswalk. United States: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2003. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/MedicareProviderSupEnroll/downloads/taxonomy.pdf. Updated 1 April 2003.

- 19.Bureau of Health Workforce and HRSA. Area Health Resources Files. Updated 31 July 2020. Accessed 1 November 2020. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf

- 20.Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. US Department of Agriculture. Last accessed 1 November 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

- 21. DePriest K, D’Aoust R, Samuel L, Commodore-Mensah Y, Hanson G, Slade EP. Nurse practitioners’ workforce outcomes under implementation of full practice authority. Nurs Outlook 2020;68:459-67. 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith LB. The effect of nurse practitioner scope of practice laws on primary care delivery. Health Econ 2022;31:21-41. 10.1002/hec.4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naylor KB, Tootoo J, Yakusheva O, Shipman SA, Bynum JPW, Davis MA. Geographic variation in spatial accessibility of U.S. healthcare providers. PLoS One 2019;14:e0215016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0215016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li F, Zaslavsky AM, Landrum MB. Propensity score weighting with multilevel data. Stat Med 2013;32:3373-87. 10.1002/sim.5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, Martsolf G. Rural and nonrural primary care physician practices increasingly rely on nurse practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:908-14. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford C. A beginner’s guide to marginal effects. https://data.library.virginia.edu/a-beginners-guide-to-marginal-effects/. Updated March 30, 2022. Accessed 1 February 2023.

- 27. Barnett ML, Bitton A, Souza J, Landon BE. Trends in outpatient care for medicare beneficiaries and implications for primary care, 2000 to 2019. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:1658-65. 10.7326/M21-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schencker L. Nurse practitioners have nearly tripled in Illinois, where they can now practice independently. Some even use the title ‘doctor.’ Should you be worried? Chicago Tribune. Published 7 February 2020. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-nurse-practitioners-doctors-increase-illinois-20200206-4x7s7quab5bctjffc7hzxrun3m-story.html

- 29. Drury M, Greenfield S, Stilwell B, Hull FM. A nurse practitioner in general practice: patient perceptions and expectations. J R Coll Gen Pract 1988;38:503-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. NONPF DNP Statement May 2018. 2018. https://www.nonpf.org/news/638126/NONPF-Statement---Reaffirming-DNP-Entry-to-Nurse-Practitioner-Practice-by-2025-.htm. Accessed 18 June 2022.

- 31. Licciardone JC. A comparison of patient visits to osteopathic and allopathic general and family medicine physicians: results from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2003-2004. Osteopath Med Prim Care 2007;1:2. 10.1186/1750-4732-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hooker RS, McCaig LF. Use of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in primary care, 1995-1999. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:231-8. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hooker RS, Everett CM. The contributions of physician assistants in primary care systems. Health Soc Care Community 2012;20:20-31. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01021.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Everett C, Thorpe C, Palta M, Carayon P, Bartels C, Smith MA. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners perform effective roles on teams caring for Medicare patients with diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1942-8. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan D, Chen Y. The productivity of professions: evidence from the emergency department (October 2022). NBER Working Paper No. w30608. 10.2139/ssrn.4262592 [DOI]

- 36. Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA 2000;283:59-68. 10.1001/jama.283.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, Watananirun K, Kontopantelis E, van Vught AJAH. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;2019:CD001271. 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams J, Russell I, Durai D, et al. Effectiveness of nurse delivered endoscopy: findings from randomised multi-institution nurse endoscopy trial (MINuET). BMJ 2009;338:b231. 10.1136/bmj.b231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kuo YF, Agrawal P, Chou LN, Jupiter D, Raji MA. Assessing association between team structure and health outcome and cost by social network analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;69:946-954. 10.1111/jgs.16962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barnes H, Richards MR, Martsolf GR, Nikpay SS, McHugh MD. Association between physician practice Medicaid acceptance and employing nurse practitioners and physician assistants: a longitudinal analysis. Health Care Manage Rev 2022;47:21-7. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dai M, Ingham RC, Peterson LE. Scope of practice and patient panel size of family physicians who work with nurse practitioners or physician assistants. Fam Med 2019;51:311-8. 10.22454/FamMed.2019.438954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Najmabadi S, Honda TJ, Hooker RS. Collaborative practice trends in US physician office visits: an analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), 2007-2016. BMJ Open 2020;10:e035414. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang N, Raji M, Lin YL, Chou LN, Kuo YF. Nurse practitioner involvement in medicare accountable care organizations: association with quality of care. Am J Med Qual 2021;36:171- 9. 10.1177/1062860620935199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Online appendix

Data Availability Statement

No additional data available.