ABSTRACT

The acute crisis of carbapenem resistance impedes the empirical use of carbapenems in medical emergencies, especially, bloodstream infections. Carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant organisms (CP-CROs) attribute high case-fatality, necessitating rapid diagnostics to initiate early targeted antibiotics. Expensive diagnostics are the major driver of antibiotic misuse, neglecting evidence-based treatment in India. One in-house molecular diagnostics assay was customized for rapid detection of CP-CROs using positive blood-culture (BC) broths at a low-cost. The assay was validated using a known-set of isolates and evaluated on positive BC broths. DNA was extracted from positive BC broths using a modified alkali-wash/heat-lysis method. One end-point multiplex-PCR was customized targeting five carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, VIM, OXA-48-, and OXA-23-type) with 16S-rDNA as internal extraction control. Carbapenem resistance due to other carbapenemases, efflux-pump activity, and loss of porins was not under the scope of the assay. Promising analytical performances (sensitivity and specificity, >90%; kappa = 0.87), encouraged to assess diagnostic value, qualified the assay for the WHO minimal requirements (both≥95%) for a multiplex-PCR. Higher LR+ (>10) and lower LR− (<0.1) indicate a good diagnostic tool for ruling in or ruling out CRO bloodstream infections. Inclusion of OXA-23-type improved assay positivity. Multiple carbapenemases were detected in>30% of samples. Good concordance was found (kappa = 0.91) with twenty-six discrepant results. The results were available in 3 hours. The running cost of the assay was US$10 per sample. Fast and reliable detection of carbapenemase(s) allows clinicians and infection-control practitioners to execute early-directed therapy and containment measures. This convenient approach facilitates implementing the assay in resource-limited healthcare settings.

KEYWORDS: Carbapenem-resistant organism, carbapenemase, bloodstream infection, rapid diagnostics, cost-effective, Multiplex-PCR

Introduction

Emerging antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which confounds patient management, especially in cases of bloodstream infection, and has been recognized as a global issue under Sustainable Development Goal 3 for achieving good health and well-being by 2030 [1,2]. In the face of limited therapeutic options, carbapenems, a subclass of beta-lactams, serve as decision-making antibiotics for severe Gram-negative bacterial infections. The World Health Organization (WHO) enlisted this critically important antimicrobial for human medicine under the watch group of the Essential Medicines List for optimal use [2]. The sustained rise of carbapenem resistance challenges public health, attributing increased mortality, medical cost, and hospital length of stay, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like India [1,3,4]. In 2017, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) published the first AMR surveillance data showing carbapenem resistance as a flagship priority in Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii, >70%), Enterobacterales (>40%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa, >30%) [5]. After that, the WHO and Department of Biotechnology in India jointly declared carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPsA), and Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) as critical pathogens in the Indian Priority Pathogen List to promote research and development on carbapenem resistance, including diagnostics [6]. Horizontal transmission of carbapenemases is accelerating the difficult-to-control and difficult-to-treat carbapenem-resistant organism (CRO) infections in community and healthcare settings [3,7]. Active carbapenem resistance surveillance is pivotal to managing CRO infections. To combat sepsis, target antibiotic therapy is recommended to be initiated within 3 hours of laboratory diagnosis, following Surviving Sepsis Guidelines [8]. In 2019, India has adopted molecular diagnostics under the national essential in vitro diagnostics list (NEDL) for effective treatment through accurate diagnosis, emphasizing indigenous AMR diagnostics [9]. High-cost commercial molecular diagnostics platforms are available for limited healthcare facilities in India, while the majority, especially in the public sector, succumbs due to poor infrastructure and resource-compromising patient management [10]. The lack of cost-effective rapid diagnostics for carbapenem resistance is escalating the issue of AMR in India [1,11]. The situation prequalifies the device for in vitro molecular diagnostics of sepsis for carbapenem resistance, especially in resource-constrained healthcare facilities, as a structural measure in antimicrobial and infection prevention stewardship. In this study, we customized an affordable and convenient molecular diagnostics approach for the rapid detection of CRO bloodstream infection sepsis cases by integrating it with existing conventional clinical microbiology facilities.

Materials and methods

Study design, site and sample

An observational prospective study was conducted at the Dept. of Biomedical Laboratory Science and Management, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal (VUWB), and the Dept. of Microbiology, Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal (NRSMCH) between February 2021 and September 2022. VUWB is a state-level public university with research facilities, and the NRSMCH is a 1920-bed tertiary-care, public hospital with resource-limited molecular microbiology settings. A molecular assay for detecting carbapenem resistance was developed and deployed at VUWB and NRSMCH, respectively. Initially, the assay was analyzed for reliability at a different point in time and across samples of pure cultures of quality control strains and spiked blood culture (BC) broth. For authentication of the assay, selected clinical isolates from the VUWB repository were validated blindly to determine analytical performance by two separate teams during February 2021 to September 2021. For evaluation, non-duplicate prospectively positive BC broths from October 2021 to September 2022 were collected at NRSMCH and tested to assess the diagnostic performance of the assay. Both monomicrobial and polymicrobial bacteremia by Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) were included. Intrinsically CROs, Gram-positive bacteria, and uncultivable organisms were excluded. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of VUWB (Committee’s ref. VU/IEC/122/2020).

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated for the evaluation study based on the recent prevalence of CRO bloodstream infection at NRSMCH 25% with a 5% margin of error and 95% confidence interval [12]. Accordingly, the sample size was 251.

Microbiological culture and carbapenem susceptibility

BC bottles for aerobes were incubated in the BacT/Alert 3D BC system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) for positivity up to 5 days. Bactec-flagged positive BC broths were screened for GNB-positive monomicrobial bacteremia and/or polymicrobial bacteremia by Gram-stain and inoculated onto both MacConkey and blood-agar plates (Difco, Sparks, MD) for overnight incubation at 37°C followed by identification using the GN-ID card and determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of carbapenems using the AST-GN81 card in the VITEK2 instrument (bioMérieux). Quality control (QC) was assessed using the strains Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. Meropenem (MEM; MIC calling range, 0.25–16 µg/ml) and imipenem (IMP; MIC calling range, 0.25–16 µg/ml) susceptibility were interpreted following the Clinical Laboratory and Standard Institute (CLSI) guideline as non-susceptible at MIC of ≥2, ≥4 and≥8 µg/ml for Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Acinetobacter spp. (EPA) and other non-fermenting (NF) GNB, respectively [13]. Elevated IMP MICs of Proteus spp., Providencia spp. and Morganella morganii due to non-carbapenemase mechanisms were ignored when considering MEM MICs. Carbapenem nonsusceptible blood isolates were preserved frozen at −70° C in brain-heart infusion broth with 15% glycerol for further molecular analysis.

Spiking and inoculation of BC bottles

The QC strains (KPC positive, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC BAA 1705; NDM positive, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC BAA 2146; OXA-48 positive, Klebsiella pneumoniae NCTC 13,442) and sequence-confirmed clinical isolates harboring single (IMP, VIM, and Oxa-23) or multiple carbapenemases were revived and matched with the 0.5 McFarland standard. BC bottles were spiked with 1 ml of 106-fold diluted bacterial culture and 5 ml of sterile sheep blood following incubation at the BacT/Alert 3D BC system (bioMérieux) [14, 15]. Flagged positive bottles were processed to assess the reliability of the assay.

Genomic DNA extraction

Boiled DNA templates were prepared from bacterial pure cultures by dissolving a single colony in 200 μl of sterile distilled water, lysing at 95°C for 10 min, and collecting the supernatant following centrifugation. Blood DNA was extracted from positive BC broths by modifying the alkali wash-heat lysis method [16]. Briefly, 1 mL of alkali wash solution (0.5 M NaOH and 0.05 M sodium-citrate) was added to 500 µl of BC broth following gentle vortexing for 10 min at room temperature and centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min. Pellet was dissolved in 500 µl of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) following centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min and as much decantation of the soup as possible. Then, the pellet was thoroughly resuspended in 100 µl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and incubated in a water bath at 95°C for 10 min, followed by a 5 min snap chill and a 10 min centrifugation at 13,000 × g. Clear supernatant (~50 µl) was stored at −20°C prior to use in PCR.

Multiplex-PCR and sequencing

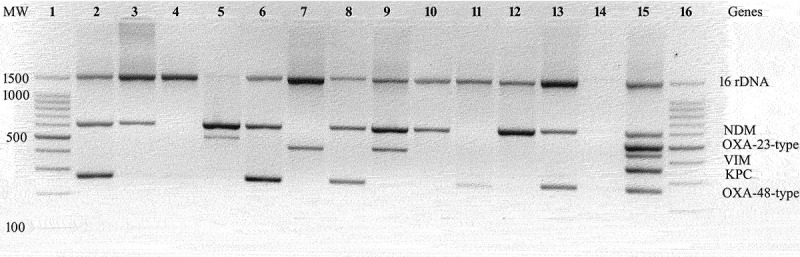

One in-house end-point multiplex-PCR (m-PCR) was customized to target five carbapenemase genes with pre-designed primers (KPC, 353bp; NDM, 603bp; VIM, 437bp; OXA-48-type, 265bp and OXA-23-type, 500bp) and the 16S rRNA gene (1350bp) as internal extraction control [17,18]. De-salted primers were procured from Eurofins (Eurofins Genomics, Bangalore, Karnataka, India) and reconstituted in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). The 25 µl amplification mixture was prepared using 12.5 µl of 2 × QIAGEN m-PCR master mix (HotStarTaq DNA polymerase, m-PCR buffer with 6 mM MgCl2 at pH 8.7 and dNTP mix) (QIAGEN, GmbH, Hilden, Germany), 0.25 µl of 20 µM of each primer and 5 µl of template DNA. PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad T100 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, US) at 95°C for 15 min followed by 30 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 50 s annealing at 57°C, 70 s extension at 72°C (extension rate of Taq DNA polymerase, 2kb/min) and a final extension step at 68°C for 10 min. PCR amplicons were analyzed on pre-EtBr stained 2.5% agarose gels at 100 V for 20 min against 100 bp DNA ladder (BR Biochem Life Sciences, New Delhi, India) and visualized using the Gel-Doc system (Bio-Rad). Additionally, a simplex-PCR was performed for the IMP gene (387bp) as described earlier [17]. Individual PCR primers were verified by amplifying and Sanger sequencing the target genes of QC strains and clinical isolates. A combined DNA extract of all target genes was used as a positive control for m-PCR. Amplification of the genes, either target(s) or internal extraction control, was considered being valid m-PCR results. In the presence of internal extraction control, no amplification of the target gene(s) was marked as a negative result. Blood DNA extract showing nonspecific amplification was repeated for m-PCR, followed by Sanger sequencing. All BC-derived carbapenem nonsusceptible isolates were retrospectively screened for the presence of carbapenemase genes to compare with the results of the assay.

Statistical analysis

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (LR+), negative likelihood ratio (LR−), and accuracy of the m-PCR were determined using MedCalc for Windows (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium), considering carbapenem nonsusceptible Enterobacterales and NF GNB by culture method as the standard. Carbapenem resistance due to other carbapenemases, efflux-pump activity, or loss of porins was not under the scope of the assay. The concordance between culture and m-PCR was analyzed using the Inter-rater agreement of Cohen’s Kappa (GraphPad Prism, CA, U.S.A).

Results

Reliability and validity

The assay reliably detected the target carbapenemase gene(s) along with the amplification of internal extraction control using QC strains and spiked BC broths following confirmation by sequencing. For validation, a total of 107 stored clinical isolates with known carbapenem susceptibility (Enterobacterales, 46; NF GNB, 34; Gram-positive cocci, 15; and yeast, 5) were checked blindly by the m-PCR assay. After decoding, the positivity rates of carbapenem resistance by BC and m-PCR were 48.6% and 49.5%, respectively. The m-PCR detected 53 CP-CROs (analytical sensitivity, 94.2%) among 49 true carbapenem nonsusceptible isolates, while the assay called 54 cases negative (analytical specificity, 92.7%) among 51 true carbapenem susceptible isolates. The concordance between BC and m-PCR was found to be very good (Kappa = 0.87). Of 53 PCR positive results, KPC, NDM, VIM, OXA-48- and OXA-23-type were noted in 2, 47, 3, 28 and 7 isolates, respectively. None of the carbapenem non-susceptible isolates tested positive for the IMP gene.

Diagnostic performance

For evaluation of the assay, a total of 295 Gram-stain-screened positive BC broths were processed, including 273 monomicrobial bacteremia and 22 polymicrobial bacteremia. BC and susceptibility categorized 118 as CROs, 159 as non-CROs, 14 as intrinsically CROs, and 4 as uncultivable organisms. A total of 277 samples were included to analyze diagnostic performances, containing Enterobacterales (n = 167), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 16), Acinetobacter spp. (n = 45) as well as other NF GNB (n = 63). The median DNA concentration, 260/280, and 260/230 ratios were 25.9 µg/ml (range, 5.6–93.5), 1.9 (range, 1.2–2.5) and 2.1 (range, 1.4–2.6) of BC broths. Diagnostic performances were assessed in three panels: EPA (n = 226), ENGN (Enterobacterales non-fermenting GNB, n = 295) and ENON (ENGN OXA-23-type negative, n = 295) (Table 1). The EPA panel had the highest accuracy (95.6%), followed by ENGN (93.1%) and ENON (90.6%). The carbapenemase gene was found in five of the 22 polymicrobial bacteremia samples. The strength of agreement between carbapenem susceptibility and m-PCR was found to be very good in EPA (Kappa = 0.91) and ENGN (Kappa = 0.86), while it was substantial in ENON (Kappa = 0.80). Among total PCR positive results (n = 119) (Figure 1), the majority was NDM (95, 79.8%), followed by OXA-48-type (47, 39.5%), OXA-23-type (24, 20.2%), VIM (5, 4.2%) and KPC (1, <1%).

Table 1.

Diagnostic performances of the m-PCR assay considering culture method as standard.

| Panel (n) | Sensitivity (%, 95% CI) |

Specificity (%, 95% CI) |

PPV (%, 95% CI) |

NPV (%, 95% CI) |

LR+ (95% CI) |

LR− (95% CI) |

Accuracy (%, 95% CI) |

Kappa (%, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA (226)a | 96.1 (90.3–98.9) |

95.2 (89.8–98.2) |

94.2 (88.2–97.3) |

96.7 (91.9–98.7) |

19.86 (9.09–43.38) |

0.04 (0.02–0.11) |

95.6 (92.0–97.9) |

0.91 (0.86–0.97) |

| ENGN (295)b | 92.4 (86.0–96.5) |

93.7 (88.7–96.9) |

91.6 (85.7–95.2) |

94.3 (89.8–96.9) |

14.69 (8.04–26.82) |

0.08 (0.04–0.15) |

93.1 (89.5–95.8) |

0.86 (0.8–0.92) |

| ENON (295)c | 86.4 (78.9–92.0) |

93.7 (88.7–96.9) |

91.1 (84.8–94.9) |

90.3 (85.5–93.6) |

13.74 (7.51–25.15) |

0.14 (0.09–0.23) |

90.6 (86.6–93.8) |

0.80 (0.74–0.88) |

Note: CI, confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; m-PCR, multiplex-PCR; EPA, Enterobacterales-Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Acinetobacter spp.; ENGN, Enterobacterales-non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli; ENON, ENF OXA-23-type negative.

a98 and 118 were true positive and true negative among 102 and 124 blood culture positive and negative samples, respectively.

b109 and 149 were true positive and true negative among 118 and 159 blood culture positive and negative samples, respectively.

c102 and 149 were true positive and true negative among 118 and 159 blood culture positive and negative samples, respectively.

Figure 1.

A representative agarose gel electrophoresis showing amplicons of multiplex-PCR using blood DNA extract. Lane 1 and 16: 100bp DNA ladder; lane 2, 6, 8 and 13: NDM and OXA-48-type; lane 3, 10 and 12: NDM; lane 4: negative result; lane 5: NDM and OXA-23-type; lane 7: VIM; lane 9: NDM and VIM; lane 11: OXA-48-type; lane 14: no template control; lane 15: positive control. MW, molecular weight (bp).

Discrepant results

Twenty-six m-PCR results were discrepant in the analytical (n = 7) and diagnostic (n = 19) panels (Table 2). Twelve carbapenem non-susceptible isolates did not harbor any of the target carbapenemases, including IMP and fourteen carbapenem susceptible isolates carried either NDM or OXA-48-type. Discrepant results of positive BC broths were matched with the results of subcultured pure isolates.

Table 2.

Discrepant results (n = 26) between blood culture and multiplex-PCR.

| Carbapenem MIC (µg/ml) & interpretationa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism (n) | MEM | IMP | Carbapenemase(s)b |

| Validation panel (7) | |||

| E. coli (1) | 4, R | ≥16, R | None |

| P. aeruginosa (1) | 8, R | 8, R | None |

| A. baumannii (1) | ≥16, R | ≥16, R | None |

| K. pneumoniae (1) | 0.5, S | ≤0.25, S | OXA-48-type |

| E. cloacae (2) | ≤0.25, S | ≤0.25, S | NDM |

| A. baumannii (1) | 0.5, S | 0.5, S | NDM |

| Evaluation panel (19) | |||

| E. coli (1) | 8, R | 4, R | None |

| E. cloacae (1) | ≥16, R | 8, R | None |

| P. aeruginosa (1) | ≥16, R | ≥16, R | None |

| Pseudomonas spp. (1) | 8, I | 8, I | None |

| A. junii (1) | 8, R | 8, R | None |

| Chryseobacterium indologenes (2) | ≥16, R | ≥16, R | None |

| Brevundimonas diminuta (1) | ≥16, R | 8, I | None |

| Burkholderia cepacia (1) | ≥16, R | ≥16, R | None |

| E. coli (2) | ≤0.25, S | 0.5–1, S | OXA-48-type |

| K. pneumoniae (1) | ≤0.25, S | ≤0.25, S | OXA-48-type |

| E. cloacae (1) | ≤0.25, S | 1, S | NDM |

| A. baumannii (1) | 0.5, S | 0.5, S | NDM |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis (2) | ≤0.25, S | 0.5–1, S | NDM/OXA-48-type |

| Sphingomonas spp. (1) | 0.5, S | 1, S | NDM |

| Achomobacter xylosoxidans (1) | 1, S | 1, S | NDM |

| Pantoae agglomerans (1) | 1, S | 0.5, S | OXA-48-type |

Note: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MEM, meropenem; IMP, imipenem; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

aMIC obtained by VITEK2 and interpretation based on clinical breakpoints available in CLSI, 2021.

bConfirmed by PCR using isolated colonies.

Assay performance time

The time for detection of carbapenemases was about 3 hours using positive BC broth, including Gram staining (~10 min), DNA extraction (~45 min), PCR amplification (~100 min), and agarose-gel electrophoresis and analysis (~20 min).

Cost analysis

A minimal amount of equipment costing about US$7,000 was required for molecular testing in clinical microbiology settings, including a thermal cycler, PCR workstation, centrifuge, vortex, micropipettes, water bath, UV-transilluminator, horizontal gel electrophoresis apparatus with power pack, and freezer (Table 3). The cost of consumables for the assay was US$7 per sample (Table 3).The running cost of the assay was US$10 per sample, including labor and overhead costs.

Table 3.

Costs of key consumables and equipment used in this study.

| Consumablesb | Unit size | Approx. cost (US$) |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex-PCR master mix | 100 reactions | 185 |

| De-salted primers (25nmole) | Six pair primer | 58 |

| Microcentrifuge tube (0.2 µl) | 500 pieces | 24 |

| Microcentrifuge tube (1.5 ml) | 500 pieces | 10 |

| 6× DNA loading dye | 1 ml | 10 |

| DNA ladder, 100 bp | 500 µl | 35 |

| 10× TE buffer, pH 8.0 | 500 ml | 25 |

| 10× TAE buffer, pH 8.3 | 500 ml | 12 |

| Agarose, low EEO | 100 g | 50 |

| Ethidium Bromide | 5 g | 36 |

| Sodium hydroxide pellet | 500 g | 4 |

| Sodium citrate tribasic dihydtare | 250 g | 8 |

| Tris-HCl | 100 g | 24 |

| Gram-stain reagent | 100 reactions | 35 |

| Total cost | 526 | |

| Equipmentc | Quantity | Approx. cost (US$) |

| Thermal cycler | One | 3,638 |

| PCR workstation | One | 485 |

| Centrifuge | Two | 365 |

| Vortex | One | 122 |

| Micropipettes | Five | 365 |

| Water-bath | One | 245 |

| UV-transilluminator | One | 250 |

| Horizontal gel electrophoresis apparatus and power pack | One | 1,212 |

| Freezer (−20° C) | One | 300 |

| Total cost | 6,982 |

aCalculating 1 US$ = 82 INR. as of November 2022.

bConsumable cost US$7 per sample.

cEquipment cost US$7,000.

Discussion

In India, carbapenem resistance has risen by 10% in the last year due to its widespread use in life-threatening infections, including sepsis [4,11]. High establishment and running costs of molecular tests are obstacles to building the capacity for molecular microbiology infrastructure, especially in crowded public hospitals in LMICs like India, driving indiscriminate use of antibiotics to treat suspected infection cases [3,10]. To combat carbapenem resistance, convenient, need-based in vitro molecular diagnostics are urgently needed, particularly in resource-limited settings in LMICs.

The ‘big five’ clinically important carbapenemase genes (KPC, NDM, VIM, IMP, and OXA-48-type) are globally predominant in CP-CROs [3,19]. NDM and OXA-48-type are endemic in India, whereas VIM and KPC are uncommon [2]. Of note, IMP was sporadically noted, mainly among CRPsA in North and South India. The IMP gene was absent in all the study CROs, including sixteen carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas spp. CRAB-carrying OXA-23-type is one of the most common pathogens of bloodstream infections leading to hospital outbreaks globally, including in India [3,11,20,21]. Based on national and regional epidemiology, the study m-PCR panel was customized using the three dominant carbapenemases (NDM, OXA-48-type, and OXA-23-type) along with two rarely encountered genes (KPC and VIM). The assay was validated and evaluated using pure isolates and positive BC broths for its use in both research and clinical settings. The target genes were detected either singly (>60%) or in combination with high positivity for NDM and low for KPC. Several research-use-only and laboratory-developed tests have been designed to screen the ‘big five’ genes, excluding OXA-23-type, in simplex- or multiplex-format and validated using only bacterial isolates [11,17–19]. Two end-point m-PCRs, one for the ‘big five’ genes and the other for CRAB-OXA genes, were previously evaluated using positive BC broths from India [24]. Among the few commercial platforms, the CE-FDA-approved BioFire FilmArray blood culture identification panel (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) is available in India for the simultaneous detection of pathogens and AMR genes, including the ‘big five’ genes [11]. Two major OXA-48 variants (OXA-181 and OXA-232), increasingly detected in Asia, were not reliably detected by commercial tests [2,22,23].

The study assay performed comparably in validation using bacterial isolates and evaluation using positive BC broths (accuracy: >90%) (Table 1). Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the EPA panel met the WHO minimal requirements (both≥95%) of the target product profile (TPP) for a multiplex platform for resistance testing of prioritized bacterial pathogens, but these fall short in the ENGN panel, including other NF GNB [25]. The study results corroborated other laboratory-developed tests and commercial platforms using pure culture and positive BC broths [11,22,23]. Of note, no clinical evaluation data were available for the BioFire FilmArray blood culture identification panel [23]. The study assay detected single and co-carbapenemase-producing CROs, even in polymicrobial bacteremia samples. But most commercial platforms, including BioFire FilmArray, miscalled the polymicrobial bacteremia, resulting in the erroneous detection of AMR genes [23].

Higher LR+ (>10) and lower LR− (<0.1) of the assay show a good diagnostic tool for ruling in or ruling out the disease, which has rarely been investigated earlier in AMR diagnostics [18,19,23]. The EPA and ENGN panels met the criteria, while the ENON panel was not reliable in determining the CRO bloodstream infections (LR−, 0.14) (Table 1). This indicated the clinical utility of this assay, including the OXA-23-type carbapenemase, which was noted in>20% of CRO bloodstream infection cases. Rapid detection of OXA-23-type strengthens infection control, preventing outbreaks and nosocomial transmission of CRAB.

Antimicrobial susceptibility results are required to be available in a clinically actionable timeframe for combating infections, especially in sepsis [8,11,21]. The study assay provided results in 3 hours, including hands-on time to decide on carbapenem use as a therapeutic option, following the Survival Sepsis guidelines. Aside from dependability and timeliness, cost has an impact on the assay’s ability to be implemented. The molecular diagnostics assay was designed to run at a cost of US$10 with equipment costs of about US$7,000 in India (Table 2). Due to the open-system format, the assay supports the need-based selection of target genes following local epidemiology and a user-friendly approach from blood DNA extraction to the analysis of m-PCR results. The commercial molecular test results are available within 2 hours, but these are close-systems and syndromic panels, requiring expensive equipment (US$20,000–25,000) and running costs (US$100–300) [19,24]. The convenient and affordable approach of the molecular diagnostics assay favors its implementation in LMICs, including India, over the other commercial platforms.

Discordant results were observed between culture and PCR for twenty-six isolates that were either carbapenem-resistant via none of the clinically important carbapenemase-mediated mechanisms or carbapenem susceptible via low or non-expression of carbapenemases (Table 2). Mechanisms of carbapenem resistance and low/non-expression of carbapenemases are reported to vary by geographic regions and even hospitals [2,3,21]. Of note, screening for carbapenemases is recommended among Enterobacterales isolates showing MEM MICs of>0.125 µg/ml that are categorized as susceptible using clinical breakpoints [3,26]. Clinical microbiologists and infectious disease specialists need to be accustomed to the scope of the assay before implementing it in patient management.

The assay was performed on blood samples enriched via culture containing bacteria of 107-109 CFU/ml, which was above the limit of detection (LoD) of most PCRs [25]. LoD of the assay is needed to determine for direct use of culture-independent blood samples containing bacteria as low as 1–10 CFU/ml. The assay was in-house evaluated using Bactec-flagged positive BC broths in one tertiary-care, public hospital in eastern India. Independent evaluation is needed using positive BC broth from automated as well as manual systems at different state- and national-level hospitals and/or diagnostics. The assay is intended to be used for CRO bloodstream infections but may be extended to other specimens, especially stool, for surveillance of carbapenem resistance.

The indigenous diagnostics approach meets the deciding criteria of the country-specific TPP for priority syndrome under the Health Technology Assessment in India for uptake in the national health system, including validation, evaluation, field feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and evidence of scalability [9]. This may be considered under NEDL for broader clinical application in different healthcare facilities in India.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to customize and assess the clinical utility of one indigenous diagnostic m-PCR panel, including OXA-23-type carbapenemase in bacterial isolates as well as BC broths. The diagnostic stewardship, which combines conventional BC and m-PCR, provides carbapenemase-based output for improved patient outcomes. The convenient molecular diagnostic approach fosters other need-based antibiotic resistance gene panels for rapid diagnosis of infectious diseases to curb AMR. Overall, the m-PCR assay may serve as a potential tool for screening, diagnostics, and surveillance to strengthen antimicrobial and infection prevention stewardship practices, especially in LMICs.

Acknowledgements

We thank the technical staffs of Dept. of Microbiology, Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata for their assistance during the collection of study blood culture samples and bacterial isolates.

Funding Statement

The study was financially supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, India, including the junior research fellowship of AM (grant no. AMR/Adhoc/241/2020-ECD-II).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Authors’ contributions

AM: Formal analysis, validation and evaluation; AR: Formal analysis and validation; SS: Formal analysis, resources of blood cultures and isolates, and writing review and editing; KCM: Formal analysis, and writing review and editing; SD: Conceptualization, supervision, methodology, and writing original draft and editing.

All authors have read and approved the final version.

References

- [1].Gandra S, Alvarez-Uria G, Turner P, et al. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in low- and middle income countries: progress and challenges in eight South Asian and Southeast Asian countries. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33(3). e00048-19. 10.1128/CMR.00048-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Das S. The crisis of carbapenemase-mediated carbapenem resistance across the human–animal–environmental interface in India. Infectious Diseases Now. 2023;53(1):104628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nordmann P, Poirel L. Epidemiology and diagnostics of carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(Supplement_7):S521–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stewardson A, Marimuthu K, Sengupta S, et al. Effect of carbapenem resistance on outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by Enterobacteriaceae in low-income and middle-income countries (PANORAMA): a multinational prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(6):601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].ICMR . Antimicrobial research surveillance network. Indian Council of Medical Research, 2021. http://iamrsn.icmr.org.in/images/pdf/AMRSNAR [Accessed November 10, 2022].

- [6].The Department of Biotechnology, Government of India . Indian priority pathogen list to guide research, discovery and development of new antibiotics in India, developed by WHO country office for India in collaboration with the department of biotechnology, Government of India, 2017. https://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/IPPL_final. [Accessed November 10, 2022]

- [7].Tilahun M, Kassa Y, Gedefie A, et al. Emerging carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infection, its epidemiology and novel treatment options: a review. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4363–4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Critical Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sharma M, Gangakhedkar RR, Bhattacharya S, et al. Understanding complexities in the uptake of indigenously developed rapid point-of-care diagnostics for containment of antimicrobial resistance in India. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(9):e006628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vira H, Bhat V, Chavan P. Diagnostic molecular microbiology and its applications: current and future perspectives. Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;1(1):20–31. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Indian Council of Medical Research . Guidance on diagnosis and management of carbapenem resistant Gram-negative infections. 2022. Accessed November 10, 2022. https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/upload_documents/Diagnosis_and_management_of_CROs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6(1):14–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 31st ed., CLSI supplement M100. 2021, Wayne, PA. https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing . EUCAST rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing (RAST) directly from positive blood culture bottles. 2020. Accessed November 10. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/RAST/EUCAST_RAST_methodology_v1.1_Final.pdf

- [15].Millar BC, Jiru X, Moore JE. Earle JAP a simple and sensitive method to extract bacterial, yeast and fungal DNA from blood culture material. J Microbial Methods. 2000;42(2):139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bogaerts P, Rezende de Castro R, de Mendonca R, et al. Validation of carbapenemase and extended-spectrum β-lactamase multiplex endpoint PCR assays according to ISO 15189. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(7):1576–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Srinivasan R, Karaoz U, Volegova M, et al. Use of 16S rRNA gene for identification of a broad range of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117617. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hansen GT. Continuous evolution: perspective on the epidemiology of carbapenemase resistance among Enterobacterales and other Gram-negative bacteria. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(1):75–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tenover FC. Using molecular diagnostics to develop therapeutic strategies for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:715821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sekyere JO, Govinden U, Essack SY. Review of established and innovative detection methods for carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;119(5):1219–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Noster J, Thelen P, Hamprecht A. Detection of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales—From ESBLs to Carbapenemases. Antibiotics. 2021;10(9):1140–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Das S, Roy S, Roy S, et al. Rapid and economical detection of eight carbapenem-resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp, and Acinetobacter spp directly from positive blood cultures using an internally controlled multiplex-PCR assay. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(6):737–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].The World Health Organization . Target product profiles for antibacterial resistance diagnostics. Geneva: WHO, 2020.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331054 [Accessed November 10, 2022] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ranganathan P, Aggarwal R. Understanding the properties of diagnostic tests – Part 2: likelihood ratios. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9(2):99–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Shehadeh F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of molecular diagnostic assays for the therapy of severe sepsis and septic shock in the emergency department. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0217508. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Opota O, Jaton K, Greub G. Microbial diagnosis of bloodstream infection: towards molecular diagnosis directly from blood. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(4):323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]