In April 2014, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the HHS Office of Population Affairs (OPA) published clinical recommendations for providing family planning services, titled Providing Quality Family Planning Services (QFP) [1]. The recommendations were developed jointly and the collaboration drew on the strengths of both agencies. CDC has a long-standing history of developing evidence-based recommendations for clinical care, and OPA’s Title X Family Planning Program has served as the national leader in direct family planning service delivery since the Title X program was established in 1970. The publication of QFP should help take the field of family planning another step closer to the ultimate goal of helping individuals and couples achieve their desired number and spacing of healthy children.

The recommendations were published at a time when there are substantial challenges to Americans’ reproductive health. One-half (49%) of the 6.7 million pregnancies each year (3.2 million) are unintended [2]. In 2006–2010, 6.7 million women aged 15–44 years had impaired fecundity (that is, had an impaired ability to get pregnant or carry a baby to term), and 1.5 million married women aged 15–44 years were infertile (that is, were unable to get pregnant after at least 12 consecutive months of unprotected sex with their husband/partner) [3]. Approximately one of every eight pregnancies in the United States results in preterm birth, and infant mortality rates remain high relative to other developed countries [4–6]. By using contraceptive services to space births and by offering preconception health services as part of family planning, the health of the infant — as well as the woman and man — can be improved [7–14].

1. What are the key recommendations contained in QFP?

The recommendations in QFP address several key areas. First, family planning services are embedded within a broader framework of preventive health services (see Fig. 1). QFP defines what services to offer clients in the context of a family planning visit, i.e., contraceptive services for clients who want to prevent pregnancy and space births, pregnancy testing and counseling, assistance to achieve pregnancy, basic infertility services, sexually transmitted disease (STD) services (including HIV testing) and other preconception health services. STD/HIV and other preconception health services are considered family planning services in QFP because they improve women’s and men’s health and can influence an individual’s ability to conceive or to have a healthy birth outcome [7,15,16]. QFP recommendations also describe how to provide contraceptive services, address the special needs of adolescent clients and highlight the importance of quality improvement. Related preventive health services include services that are considered beneficial to reproductive health, are closely linked to family planning services, and are appropriate to deliver in the context of a family planning visit, but do not directly contribute to achieving or preventing pregnancy. Breast and cervical cancer screening are examples. Other preventive services, such as screening for lipid disorders or skin cancer, are noted as important but not closely related to reproductive health so they are not addressed in QFP.

Fig. 1.

Family planning, related preventive services and other preventive health services.

2. What process was used to develop the recommendations?

When developing the recommendations, efforts were made to develop them in a manner that was consistent with the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) standards for “trustworthy” clinical practice guidelines.

One IOM standard is to form a guidelines development group, and several of the nation’s leading experts in family planning services agreed to play this role throughout the process of developing QFP. These individuals worked to advise on the structure and content of the revised recommendations, to review draft recommendations, and to ensure that the recommendations were feasible and relevant to the needs of the field (see Appendix A for a list of the members of the Expert Work Group).

A central premise underpinning the recommendations is that improving the quality of family planning services will lead to improved reproductive health outcomes [17–19]. The IOM defines health care quality as “the degree to which health-care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [17,20]. According to the IOM, quality health care has the following attributes: safe, effective, client-centered, timely, efficient, accessible, equitable and of value. Grounding QFP into the larger national discussion about health care quality care aligns the recommendations with an important national movement to which we can both contribute and learn from.

Emphasis was placed on ensuring that the recommendations were as evidence based as possible and that decisions were made in a fully transparent manner. Toward that end, extensive efforts were made to synthesize existing clinical guidelines, to conduct systematic reviews of the literature in priority areas and to document the processes used to develop recommendations.

3. Why are these recommendations important?

QFP provides an expansive definition of family planning services that includes a comprehensive set of services both for preventing unintended pregnancies and for achieving healthy pregnancies and positive birth outcomes. The recommendations describe what services should be offered in a family planning visit, and also describe how these services should be provided. QFP makes a unique contribution in defining the range of services that should be offered in a family planning setting, emphasizing the role of helping clients achieve as well as prevent pregnancy, describing how to provide pregnancy testing and counseling services, and highlighting the role that quality improvement can play in improving health outcomes. The needs of both female and male clients are addressed, and all providers, including primary care providers, are encouraged to assess reproductive intention and the need for services related to preventing or achieving pregnancy, even when that is not the primary reason for the visit.

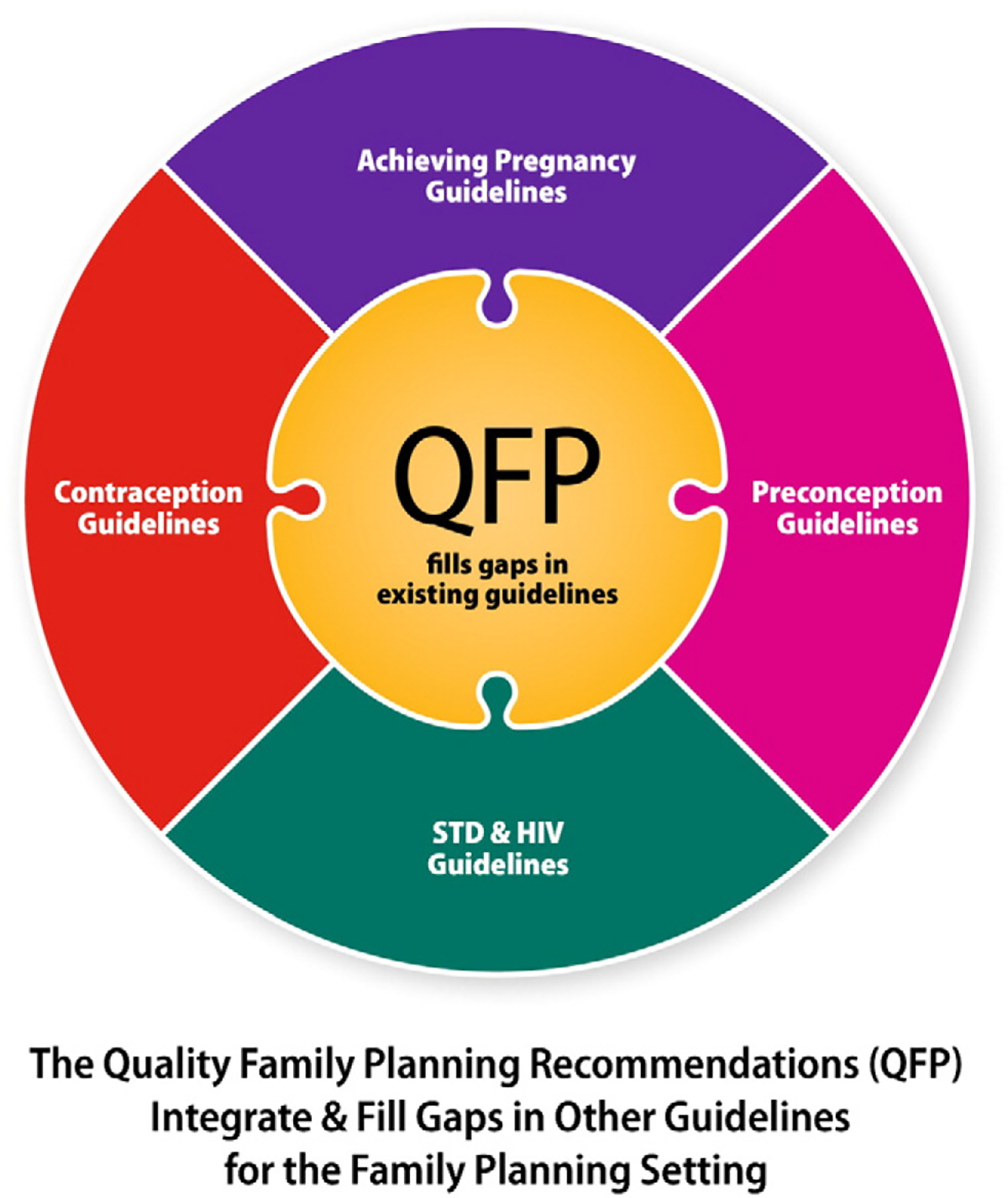

QFP complements existing guidelines in two main ways (see Fig. 2). First, it integrates existing guidelines that are appropriate for use in the family planning setting. These guidelines are often used in a siloed, isolated manner. Integrating existing recommendations into a combined set of guidelines should make them more accessible and useful to clinical providers. Toward this end, QFP integrates CDC’s U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (MEC) [21], US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (SPR) [22], STD Treatment Guidelines [23], Recommendations for HIV testing in Health Care Settings[24] and Recommendations for Preconception Health Care[7]. Numerous other clinical guidelines developed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and professional medical associations such as the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the American Urological Association are also referenced.

Fig. 2.

How QFP complements other clinical recommendations.

QFP also goes one step further and fills gaps in existing guidelines. For example, QFP provides detailed guidance on how to provide contraceptive services. This includes recommendations for how to integrate MEC and SPR into the clinical process, how to counsel and educate clients about contraceptive choice and use, how to work with male clients about pregnancy prevention, and how to address the special needs of adolescent clients such as the role of confidential services while acknowledging the importance of encouraging parent–child communication when possible.

4. What will change as a result of QFP?

There are at least four things that we hope will happen as a result of the publication, dissemination and implementation of QFP:

The quality of contraceptive services will improve. QFP provides detailed guidance designed to provide contraceptive services in such a way that they meet several of the IOM’s dimensions of quality, including safe (per MEC), client-centered (clients are informed about all methods but their preferences are respected), effective (education includes informing clients about the relative effectiveness of different contraceptive methods) and efficient (unnecessary barriers to contraception are removed).

Family planning visits will be recognized as an opportunity to meet a broader set of clients’ reproductive health needs. This includes helping female and male clients achieve or prevent pregnancy according to their desires, promoting healthy pregnancies through preconception health services, and offering related preventive health services. All of these services can improve women’s and men’s health, regardless of whether they choose to have children.

More primary care providers will screen clients about their pregnancy intention and reproductive life plans, and provide services designed to help them prevent or achieve pregnancy. With half of pregnancies unintended in the United States, we will need the active involvement of primary care providers, many of whom have not traditionally provided these services. It is our hope that QFP will help give these providers the guidance and information they need to do so with confidence and in a more effective manner.

QFP will stimulate future efforts to strengthen the field of family planning, with scientific evidence being the primary driver of change. QFP’s use of the IOM’s framework of health care quality provides a launching pad for efforts related to performance measurement and quality improvement. The systematic reviews of the literature identified numerous gaps in research that we hope will be filled in the future, to be cycled back into future updates of QFP to continually refresh and strengthen the evidence base. Surveillance efforts can monitor coverage of the services recommended in QFP, and highlight sub-populations where the need for services is not being met.

In summary, the publication and implementation of QFP should contribute to helping all individuals and couples achieve their desired number and spacing of children (even if that means no children) and increase the likelihood that those children are born healthy. The process of developing the recommendations led to a heightened awareness of the needs of health care providers and their clients — we hope that the publication and implementation of QFP will move us closer to meeting those needs. Finally, the important contributions of the many individuals who contributed so generously of their time, patience and expertise to the development of these recommendations must be acknowledged — QFP would not exist without their assistance.

Appendix A. Expert Work Group Members

The individuals listed below served as members of the Expert Work Group that advised CDC and OPA in the development of Providing Quality Family Planning Services. The affiliations were current as of the time that the Expert Work Group was first formed. Many other individuals contributed as technical panel members and reviewers; a full list of all contributors is found in the guidelines document itself.

Courtney Benedict, Marin Community Clinics

Jan Chapin, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Clare Coleman, National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association

Vanessa Cullins, Planned Parenthood Federation of America Daryn Eikner, Family Planning Council

Mark Hathaway, Unity Health Care and Washington Hospital Center

Seiji Hayashi, Bureau of Primary Health Care, Health Resources and Services Administration

Beth Jordan, Association of Reproductive Health Professionals

Ann Loeffler, John Snow Research and Training Institute

Arik V. Marcell, The Johns Hopkins University and the Male Training Center

Tom Miller, Alabama Department of Health

Deborah Nucatola, Planned Parenthood Federation of America

Michael Policar, State of California and UCSF Bixby Center

Adrienne Stith-Butler, Keck Center of the National Academies of Science

Denise Wheeler, Iowa Department of Public Health

Gayla Winston, Indiana Family Health Council

Jacki Witt, Clinical Training Center for Family Planning, University of Missouri–Kansas City

Jamal Gwathney, Bureau of Primary Health Care, HRSA

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the Office of Population Affairs.

References

- [1].CDC. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of the CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014;63:1–54 [Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6304a1.htm?s_cid=rr6304a1_w]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011;84:478–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chandra A, Copen C, Steven EH. Infertility and Impaired Fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, No. 67; 2013. [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr067.pdf]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Macdorman M, Mathews T. Recent trends in infant mortality in the United States. NCHS data brief, no 9. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman J, et al. Births: final data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2013;62:78 [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_09.pdf]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, Frick C. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].CDC. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care — United States. MMWR 2006;55:1–23 [Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5506.pdf]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen I, Jhangri GS, Chandra S. Relationship between interpregnancy interval and congenital anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014. Jun;210 (6):564.e1–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.02.002. Epub 2014 Feb 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Castano F, Norton MH. Effects of birth spacing on maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health: a systematic review of causal mechanisms. Stud Fam Plann 2012;43:93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2006;295:1809–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Effects of birth spacing on maternal health: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Howard EJ, Harville E, Kissinger P, Xiong X. The association between short interpregnancy interval and preterm birth in Louisiana: a comparison of methods. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kozuki N, Lee AC, Silveira MF, et al. The associations of birth intervals with small-for-gestational-age, preterm, and neonatal and infant mortality: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2013;13 Suppl 3:S2. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S2. Epub 2013 Sep 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shachar BZ, Lyell DJ. Interpregnancy interval and obstetrical complications. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2012;67:584–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jack B, Atrash H, Coonrod D, Moos M, O’Donnell J, Johnson K. The clinical content of preconception care: an overview and preparation of this supplement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:S266–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Frey K, Navarro S, Kotelchuck M, Lu M. The clinical content of preconception care: preconception care for men. AJOG 2008:S389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies of Science; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bruce J. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Stud Fam Plann 1990;21:61–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Becker D, Koenig MA, Kim YM, Cardona K, Sonenstein FL. The quality of family planning services in the United States: findings from a literature review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2007;39:206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Institute of Medicine. Future directions for the national health care quality and disparities reports. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].CDC. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–86 [Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr59e0528a1.htm]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].CDC. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use 2013. MMWR 2013;62:1–60 [Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6205a1.htm?s_cid=rr6205a1_w]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR 2010;59:1–116 [Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].CDC. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents and pregnant women in health care settings. MMWR 2006;55:1–17 [Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5514a1.htm]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]