Abstract

Background

It has been shown that patient demographics such as age, payer factors such as insurance type, clinical characteristics such as preoperative opioid use, and disease grade but not surgical procedure are associated with revision surgery to treat cubital tunnel syndrome. However, prior studies evaluating factors associated with revision surgery after primary cubital tunnel release have been relatively small and have involved patients from a single institution or included only a single payer.

Questions/purposes

(1) What percentage of patients who underwent cubital tunnel release underwent revision within 3 years? (2) What factors are associated with revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of primary cubital tunnel release?

Methods

We identified all adult patients who underwent primary cubital tunnel release from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2017, in the New York Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System database using Current Procedural Terminology codes. We chose this database because it includes all payers and nearly all facilities in a large geographic area where cubital tunnel release may be performed. We used Current Procedural Terminology modifier codes to determine the laterality of primary and revision procedures. The mean age of the cohort overall was 53 ± 14 years, 43% (8490 of 19,683) were women, and 73% (14,308 of 19,683) were non-Hispanic White. The Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System database organization does not include a listing of all state residents and thus does not allow for censoring of patients who move out of state. All patients were followed for 3 years. We developed a multivariable hierarchical logistic regression model to model factors independently associated with revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years. Key explanatory variables included age, gender, race or ethnicity, insurance, patient residential location, medical comorbidities, concomitant procedures, whether the procedure was unilateral or bilateral, and year. The model also controlled for facility-level random effects to account for the clustering of observations among these entities.

Results

The risk of revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of the primary procedure was 0.7% (141 of 19,683). The median time to revision cubital tunnel release was 448 days (interquartile range 210 to 861 days). After controlling for patient-level covariates and facility random effects, and compared with their respective counterparts, the odds of revision surgery were higher for patients with workers compensation insurance (odds ratio 2.14 [95% confidence interval 1.38 to 3.32]; p < 0.001), a simultaneous bilateral index procedure (OR 12.26 [95% CI 5.93 to 25.32]; p < 0.001), and those who underwent submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve (OR 2.82 [95% CI 1.35 to 5.89]; p = 0.006). The odds of revision surgery were lower with increasing age (OR 0.79 per 10 years [95% CI 0.69 to 0.91]; p < 0.001) and a concomitant carpal tunnel release (OR 0.66 [95% CI 0.44 to 0.98]; p = 0.04).

Conclusion

The risk of revision cubital tunnel release was low. Surgeons should be cautious when performing simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release and when performing submuscular transposition in the setting of primary cubital tunnel release. Patients with workers compensation insurance should be informed they are at increased odds for undergoing subsequent revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years. Future work may seek to better understand whether these same effects are seen in other populations. Future work might also evaluate how these and other factors such as disease severity could affect functional outcomes and the trajectory of recovery.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Outcomes after surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome are generally positive, with most patients reporting symptom improvement postoperatively [9, 14, 24]. However, some patients have persistent or recurrent symptoms and may undergo revision cubital tunnel release [1, 20]. Prior studies have reported that younger age, workers compensation insurance, preoperative opioid use, McGowan Stage I disease, shorter duration of symptoms, and medical comorbidities but not surgical procedure (in situ decompression versus transposition of the ulnar nerve) were associated with revision cubital tunnel release surgery [5, 9, 10, 14, 23, 24]. However, these findings likely have limited generalizability given their focus on single institutions or single payers.

Information on factors that could make patients with cubital tunnel syndrome more unlikely to experience less favorable outcomes such as undergoing revision cubital tunnel release may help to inform decision-making for patients and surgeons. For example, if it were shown that patients undergoing in situ cubital tunnel release or submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve were to have superior outcomes, then surgeons may be more likely to perform one surgery over the other in the setting of primary surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Similarly, if patients with specific demographic characteristics were shown to have differing rates of revision cubital tunnel release, then this knowledge may alter the conversation between the patient and surgeon as to the relative risks and benefits of surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Prior studies investigating revision cubital tunnel release were relatively small and involved patients from a single institution or included only a single payer and thus may have limitations of generalizability (single institution) or unique payment constraints (single payer).

Therefore, we asked: (1) What percentage of patients who underwent cubital tunnel release underwent revision within 3 years? (2) What factors are associated with revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of primary cubital tunnel release?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective, comparative study drawn from a large database. We used the 2011 to 2017 outpatient and ambulatory surgery files from the New York Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) database for our study.

Data Sources

The SPARCS dataset is a comprehensive, deidentified reporting system for all payers that collects patient-level data on patient characteristics, diagnoses, treatment, services, and charges for inpatient hospital admissions, ambulatory surgery, emergency department visits, and other outpatient data from New York State. We chose this database because it includes nearly all facilities in New York State where revision cubital tunnel release may be performed and hence is not limited by sampling bias. Moreover, the database also includes all payers and therefore increases the generalizability of our results. SPARCS has been used to examine outcomes after upper extremity orthopaedic procedures including medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction and total shoulder arthroplasty [6, 12].

Patients

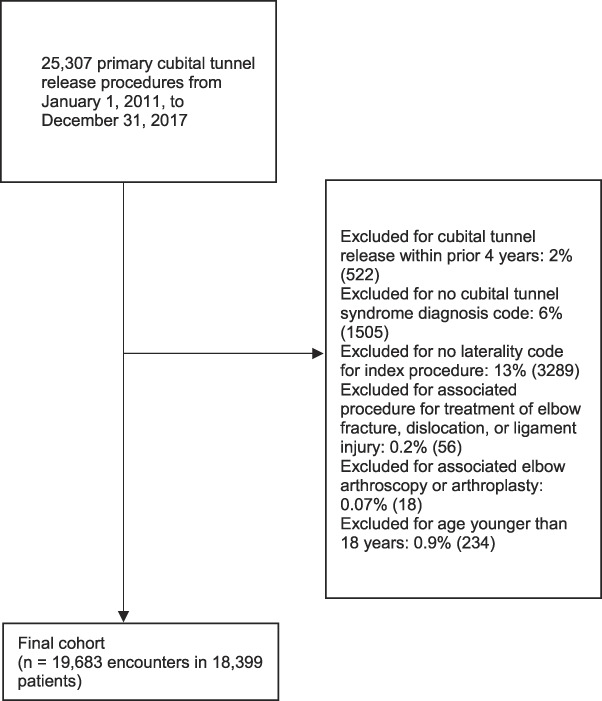

We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (Supplemental Table 1; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B71) to identify all encounters for cubital tunnel release and associated procedures in New York State from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2017. We initially identified 25,307 primary cubital tunnel release procedures. We excluded any patients with prior cubital tunnel release in the previous 4 years (n = 522); no cubital tunnel syndrome diagnosis code identified using 345.2 for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9-Clinical Modification and codes starting with G56.2 for the ICD-10-Clinical Modification (1505); no laterality identified at the time of the index procedure (3289); concomitant procedure for the treatment of elbow fracture, dislocation, or ligament injury (56); concomitant elbow arthroscopy or arthroplasty (18); and age younger than 18 years (234). Our final analytic cohort consisted of 19,683 encounters for 18,399 patients (Fig. 1). All patients had a laterality modifier for both index cubital tunnel release and revision cubital tunnel release if the patient underwent revision surgery.

Fig. 1.

This flowchart shows the patient inclusion and exclusion process.

We identified procedures associated with submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve using CPT codes according to recommendations from the American Association for Hand Surgery as described (CPT code 64718 for cubital tunnel release along with CPT code 24305 for submuscular transposition) [11]. We defined simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release as an encounter for cubital tunnel release with a modifier code of 50 indicating bilateral surgery or CPT modifier codes indicating laterality as both left and right at the same encounter. Staged bilateral cubital tunnel release was defined as two separate unilateral cubital tunnel release procedures with differing laterality within 42 days, a time interval previously used to identify staged carpal tunnel release procedures [15]. We obtained county-level rural-urban continuum codes from the United States Department of Agriculture [22]. To appropriately exclude patients with prior cubital tunnel release procedures within 4 years, we used the 2007 to 2010 outpatient and ambulatory surgery files from SPARCS in addition to the 2011 to 2017 files. The 2018 to 2020 outpatient and ambulatory surgery files from SPARCS were used in addition to the 2011 to 2017 files to evaluate outcomes within 3 years.

Descriptive Data

The mean age of the cohort overall was 53 ± 14 years, 43% (8490 of 19,683) were women, and 73% (14,308 of 19,683) were non-Hispanic White. Forty-two percent (8336 of 19,683) had private insurance, 23% (4427 of 19,683) had Medicare insurance, 12% (2329 of 19,683) had Medicaid insurance, 15% (2928 of 19,683) had workers compensation insurance, and 8% (1663 of 19,683) had other insurance. Thirty-five percent (6945 of 19,683) underwent concomitant carpal tunnel release, 3% (643 of 19,683) underwent concomitant other hand or wrist procedures, 0.6% (124 of 19,683) underwent simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release, 1.1% (225 of 19,683) underwent staged bilateral cubital tunnel release within 42 days, and 2% (409 of 19,683) underwent submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients who did versus did not undergo revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years after the primary procedure

| Parameter | No revision within 3 years (n = 19,542) | Revision within 3 years (n = 141) |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 53 ± 14 | 47 ± 14 |

| Women gender, % (n) | 43 (8425) | 46 (65) |

| Race or ethnicity, % (n) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7 (1410) | 9 (12) |

| Hispanic | a | a |

| Non-Hispanic White | 73 (14,208) | 71 (100) |

| Other | 17 (3339) | 16 (22) |

| Number of medical comorbidities, % (n) | ||

| 0 | 67 (12,997) | 72 (102) |

| 1 | 16 (3116) | 11 (15) |

| 2 or more | 18 (3429) | 17%(24) |

| Insurance, % (n) | ||

| Private | 42 (8290) | 33 (46) |

| Medicare | 23 (4406) | 15 (21) |

| Medicaid | 12 (2305) | 17 (24) |

| Workers compensation | 15 (2891) | 26 (37) |

| Other | 8 (1650) | 9 (13) |

| Patient residential location, rural, % (n) | 16 (3069) | 19 (27) |

| Carpal tunnel release, % (n) | 35 (6910) | 25 (35) |

| Other concomitant hand/wrist procedure | a | a |

| Unilateral versus bilateral, % (n) | ||

| Unilateral | 98 (19,205) | 92 (129) |

| Simultaneous bilateral | a | a |

| Staged bilateral | a | a |

| Submuscular transposition | a | a |

| Year, % (n) | ||

| 2011 | 13 (2445) | 21 (29) |

| 2012 | 13 (2598) | 12 (17) |

| 2013 | 13 (2585) | 10 (14) |

| 2014 | 14 (2768) | 14 (19) |

| 2015 | 15 (2971) | 12 (17) |

| 2016 | 16 (3164) | 20 (28) |

| 2017 | 15 (3011) | 12 (17) |

Race and ethnicity are self-reported by the patient in SPARCS.

aIndicates masked values in a row with at least one cell containing a value of less than 11 per SPARCS publication policy.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years after the index procedure. We defined revision cubital tunnel release as any repeat CPT code for cubital tunnel release with a CPT modifier code indicating either a bilateral or ipsilateral procedure at the time of the repeat surgery. Any future procedure with the same laterality as the primary procedure was considered revision cubital tunnel release. For patients undergoing bilateral cubital tunnel release at the time of the index procedure, any future procedure during the study period was considered a revision procedure.

Key Explanatory Variables

To evaluate the association of revision cubital tunnel release with patient-level factors, we used the following patient-level variables: a continuous indicator for age, and categorical indicators for patient race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and other, as reported by the patient in SPARCS), gender (men or women), insurance type (private, Medicare, Medicaid, workers compensation, or other), residential location (urban or rural; rural-urban continuum code values of 1 to 3 or 4 to 9, respectively), number of comorbidities identified by the Elixhauser algorithm [4, 19] (zero, one, or multiple), whether the patient underwent concomitant carpal tunnel release, whether the patient underwent other concomitant hand or wrist procedures (surgical treatment of thumb carpometacarpal arthritis, trigger finger release, or extensor tendon release), whether the patient underwent bilateral cubital tunnel release (unilateral, simultaneous bilateral, or staged bilateral within 6 weeks), whether the patient underwent submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve, and year of the index procedure. We used the New York Permanent Facility Identifier to identify facilities where the surgeries were performed.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board, study number STUDY00002011.

Statistical Analysis

We first evaluated the rate of revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of the index procedure. We defined this rate as the number of patients who underwent revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of primary cubital tunnel release divided by the number of patients undergoing primary cubital tunnel release. The SPARCS database does not include a listing of all state residents and thus does not allow for censoring of patients who move out of state or die. All patients were followed for 3 years; this is within the range of mean or median follow-up in other studies (12 to 34.5 months) [5, 8, 25] and inclusive of the reported mean or median time to revision (7.9 to 30 months) [2, 5, 8]. We estimated a multivariable hierarchical logistic regression model to evaluate the association between the key explanatory variables and the odds of undergoing revision cubital tunnel release. The model also controlled for facility-level random effects to account for the clustering of observations among these facilities. The statistical analysis was performed using Stata 17 (StataCorp). A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sensitivity Analysis

To check for the robustness of our main findings, we estimated a model for the outcome of revision cubital tunnel release within 5 years of the index procedure. The cohort for this analysis extended from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2015. We also re-estimated the model by revising the definition of revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years to include any cubital tunnel release procedure after the primary procedure with no laterality identified from procedure modifier codes, in addition to those repeat procedures with the same laterality as the primary procedure to obtain a more inclusive estimate.

Results

Risk of Revision Cubital Tunnel Release Within 3 Years of Primary Cubital Tunnel Release

A total of 0.7% (141 of 19,683) of the primary cubital tunnel procedures performed during the study period underwent revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of the index procedure. The median time to revision cubital tunnel release was 448 days (interquartile range 210 to 861 days). On redefining revision surgery as any repeat ipsilateral procedure or repeat procedure with missing laterality, the risk of revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years was 0.9% (147 of 19,683 patients) (Supplemental Table 2; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B72). A total of 0.8% (112 of 13,351) of the patients underwent revision cubital tunnel release within 5 years (Supplemental Table 3; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B73).

Factors Associated With Revision Cubital Tunnel Release Within 3 Years of Primary Cubital Tunnel Release

After controlling for patient-level covariates and facility random effects and compared with their respective counterparts, the odds of revision surgery were higher for patients with workers compensation insurance (OR 2.14 [95% confidence interval 1.38 to 3.32]; p < 0.001), simultaneous bilateral index procedures (OR 12.26 [95% CI 5.93 to 25.32]; p < 0.001), and those who underwent submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve (OR 2.82 [95% CI 1.35 to 5.89]; p = 0.006) (Table 2). The odds of revision surgery were lower with increasing age (OR 0.79 per 10 years [95% CI 0.69 to 0.91]; p < 0.001) and a concomitant carpal tunnel release (OR 0.66 [95% CI 0.44 to 0.98]; p = 0.04). Other patient-level factors were not associated with revision cubital tunnel release. The estimates from the multivariable models in the sensitivity analysis were generally consistent with the main findings, but a concomitant carpal tunnel release was not protective against revision cubital tunnel release within 5 years, whereas having one medical comorbidity was protective. Medicaid insurance was associated with revision surgery within 3 years using the more-inclusive estimate of revision cubital tunnel release (Supplemental Table 2; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B72).

Table 2.

Results of multivariable logistic regression for revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of the primary cubital tunnel release (n = 19,683)

| Parameter | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.91) | < 0.001 |

| Women gender | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.55) | 0.57 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | Reference | |

| Hispanic | 1.28 (0.49 to 3.34) | 0.61 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.85 (0.46 to 1.58) | 0.62 |

| Other | 0.76 (0.37 to 1.57) | 0.46 |

| Number of medical comorbidities | ||

| 0 | Reference | |

| 1 | 0.67 (0.39 to 1.17) | 0.16 |

| 2 or more | 1.08 (0.67 to 1.74) | 0.75 |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | Reference | |

| Medicare | 1.29 (0.73 to 2.28) | 0.38 |

| Medicaid | 1.64 (0.98 to 2.74) | 0.06 |

| Workers compensation | 2.14 (1.38 to 3.32) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 1.42 (0.76 to 2.66) | 0.27 |

| Rural location | 1.24 (0.81 to 1.92) | 0.32 |

| Carpal tunnel release | ||

| Concomitant carpal tunnel release | 0.66 (0.44 to 0.98) | 0.04 |

| Other concomitant soft hand/wrist procedure | ||

| Concomitant hand/wrist procedure | 1.24 (0.49 to 3.11) | 0.65 |

| Unilateral versus bilateral | ||

| Unilateral | Reference | |

| Simultaneous bilateral | 12.26 (5.93 to 25.32) | < 0.001 |

| Staged bilateral | 2.17 (0.68 to 6.93) | 0.19 |

| Procedure | ||

| Submuscular transposition | 2.82 (1.35 to 5.89) | 0.006 |

| Year | ||

| 2011 | Reference | |

| 2012 | 0.53 (0.29 to 0.97) | 0.04 |

| 2013 | 0.45 (0.24 to 0.85) | 0.02 |

| 2014 | 0.56 (0.31 to 1.00) | 0.05 |

| 2015 | 0.46 (0.25 to 0.85) | 0.01 |

| 2016 | 0.69 (0.40 to 1.17) | 0.17 |

| 2017 | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.91) | 0.03 |

ORs, 95% CIs, and p values are presented for the model controlling for patient factors and random effects for facility. Race and ethnicity are self-reported by the patient in SPARCS.

Discussion

Most patients report symptom improvement after surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome [9, 14, 24]. Information on the effect of surgical procedure or patient demographic characteristics on odds of revision cubital tunnel release would help inform decisions on which surgical procedure to perform and the relative risks and benefits of surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Prior studies have reported that demographic information, disease characteristics, and medical comorbidities but not surgical procedure are associated with revision cubital tunnel release [5, 9, 10, 14, 23, 24], but prior work has focused largely on single institutions or included only a single payer. In our all-payer statewide study, we found that the rate of revision cubital tunnel release was lower than reported previously. We also demonstrated that the odds of revision surgery were higher among those who underwent bilateral simultaneous cubital tunnel release, had workers compensation insurance, or underwent submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve, and that older age and concomitant carpal tunnel release were associated with lower odds of revision surgery. Surgeons should be cautious when performing simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release and when performing submuscular transposition in the setting of primary cubital tunnel release. Patients with workers compensation insurance should be told they are at increased odds for undergoing revision cubital tunnel release.

Limitations

First, our study analyzed administrative claims data and depended on reliable coding of variables. However, the SPARCS data are rigorously monitored and validated, and checks are in place including periodic audits, if needed, to ensure accuracy of the data. Second, we do not have data on patient symptoms, severity of disease, findings on electrodiagnostic studies, postoperative pain, postoperative function, or why patients chose to undergo primary or revision surgery. Although these factors may affect the outcome, the distribution of these factors is likely to remain consistent through the study period, and hence we do not expect them to substantially confound our inferences with respect to factors associated with revision cubital tunnel release. Third, some patients may experience a poor clinical outcome but may not undergo revision surgery for a number of reasons, including not being offered revision surgery, and these poor outcomes would not be captured in our dataset. However, it is not feasible to evaluate subjective clinical outcome or symptom severity before or after surgery in a dataset of this nature. Factors associated with poor clinical outcome would be a potential area for future research. Fourth, it is possible that patients underwent revision cubital tunnel release at a facility outside New York State or underwent primary cubital tunnel release in another state and revision cubital tunnel release in New York State. We expect this number to be relatively small, and we attempted to minimize this limitation by only including patients who were residents of New York State. Fifth, although individual surgeon factors such as specialty, annual volume, or years practicing may influence the outcome of the likelihood of revision surgery, the rarity of revision surgery precludes an estimation of the surgeon effect. Sixth, patients may have actually undergone primary cubital tunnel release within 4 years before the procedure coded as primary cubital tunnel release in our study. However, given the timepoint at which revision cubital tunnel release is typically performed (8 to 30 months), we expect this number to be small [2, 5, 8]. Lastly, although SPARCS includes claims from hospital-affiliated and freestanding healthcare facilities, some facilities are not included; therefore, our findings can only be generalized to the facilities included in the present study. We expect that only a small number of procedures would be performed in facilities not captured in our dataset, and the impact of this limitation would be relatively small.

Risk of Revision Cubital Tunnel Surgery Within 3 Years of Primary Cubital Tunnel Release

In our study, the risk of revision cubital tunnel release was lower than that reported previously. Camp et al. [2] evaluated outcomes after cubital tunnel release in the Medicare population and found a 1.4% rate of revision cubital tunnel release among patients with at least 2 years of follow-up. Other studies involving patients from a single institution reported a considerably higher rate of revision cubital tunnel release, from 5.7% to 24% [5, 8, 25]. Given that revision cubital tunnel release is an elective procedure, and different surgeons and patients may have different reasons to pursue revision cubital tunnel release, there may be variation in rates of revision cubital tunnel release across institutions and regions for a number of reasons including patient demands, practice environments, and differences in rates of litigation in different regions. This may explain the substantially different rates of revision surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome in single-institution studies. We suspect that our reported rate of revision cubital tunnel release may be more accurate for the general population than that reported in the study by Camp et al. [2] because we included all payers, although we cannot rule out differences in practice patterns between New York State and the rest of the United States.

Factors Independently Associated With Revision Cubital Tunnel Surgery Within 3 Years of Primary Cubital Tunnel Release

We found that that submuscular transposition was associated with revision cubital tunnel release. Surgeons could consider avoiding submuscular transposition in the setting of primary cubital tunnel release. This finding is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. [25], who reported that ulnar nerve transposition (subcutaneous or submuscular) was associated with secondary surgery. Although nine of the 10 patients with ulnar nerve transposition who underwent reoperation in their study underwent submuscular rather than subcutaneous transposition, the authors did not specifically report the association of submuscular versus subcutaneous transposition with the risk of revision surgery [25]. Our findings are inconsistent with those of a meta-analysis comparing in situ decompression with ulnar nerve transposition that focused on observational studies [17]. The study suggested there was no difference in the odds of revision surgery between the two surgical techniques. However, their study only included 759 patients in the analysis for the outcome of revision surgery and may have been underpowered to detect differences between groups. Our finding of an association between submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve at the time of the primary procedure and revision cubital tunnel release should be interpreted cautiously given the relatively small number of patients in our study undergoing submuscular transposition. It would be beneficial to evaluate the association between surgical procedure in the primary treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome and other outcomes such as postoperative pain and function.

We found that demographic and other clinical factors such as younger age, insurance (workers compensation), and simultaneous bilateral primary cubital tunnel release were associated with revision cubital tunnel release, while concomitant carpal tunnel release was protective. Surgeons should inform younger patients, patients with workers compensation insurance, and patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release that they may be at increased risk of revision surgery. These findings agree with prior work [2, 5, 7] (Table 3). Our findings extend the prior work by confirming the findings in this multi-institutional rather than single-institution study and by including multiple payers rather than only Medicare. It is unclear why these trends are seen. However, studies have reported that there are differences in the severity of cubital tunnel syndrome at the time of presentation by insurance type [3] as well as differences in patient expectations of the outcome of cubital tunnel release by insurance type [16], and these findings may affect postoperative outcomes. It is unclear why patients with workers compensation insurance may be at higher risk of revision surgery. Age younger than 48 years has been shown to be associated with more physically demanding jobs for patients undergoing surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome [18]. If the older patients in our study also had less-demanding jobs or were retired or not working, they may have found persistent or recurrent symptoms less problematic and would have chosen not to undergo revision surgery. Patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release have been a subset of patients in larger studies [13, 21], but a subgroup analysis was not reported, and there has been little documented in terms of indications, outcomes, or complications. Patients undergoing concomitant carpal tunnel release may have lower odds of undergoing revision cubital tunnel release because of a more aggressive initial procedure and surgeons potentially thinking that everything had been done during the primary surgery. Alternatively, the relief of nighttime awakening commonly associated with carpal tunnel syndrome may have provided enough symptom relief that any residual numbness was not bothersome enough for revision surgery. This finding agrees with that reported by Krogue et al. [10].

Table 3.

Comparison of demographic and clinical factors associated with revision carpal tunnel release in other studies and the present study

| Factor | Findings in other studies | Findings in the present study |

| Age | Camp et al. [2]: Age younger than 65 years was associated with revision cubital tunnel release. Hutchinson et al. [7]: Older age was protective against performance of revision cubital tunnel release. |

Older age was protective against cubital tunnel release. |

| Insurance | Gaspar et al. [5]: Workers compensation insurance associated with revision surgery. | Workers compensation insurance was associated with revision surgery. |

| Concomitant procedures | Krogue et al. [10]: Concomitant procedures were protective against revision surgery. | Concomitant carpal tunnel release as protective against revision surgery. Other concomitant procedures were not associated with revision surgery. |

Conclusion

We showed that revision cubital tunnel release within 3 years of primary surgery is relatively uncommon, and that simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release, submuscular ulnar nerve transposition, and workers compensation insurance were associated with revision surgery within 3 years, whereas older age and concomitant carpal tunnel release were protective. Surgeons should be cautious when performing simultaneous bilateral cubital tunnel release and when performing submuscular transposition in the setting of primary cubital tunnel release. Patients with workers compensation insurance should be informed they are at increased odds of undergoing revision cubital tunnel release. Future work could seek to better understand whether these same effects are seen in other populations. Future work could evaluate how these and other factors such as disease severity may affect functional outcomes and the trajectory of recovery. Future studies should also include payers other than Medicare, because we observed differences in the likelihood of undergoing revision surgery by insurance type. This population might not represent the typical patient undergoing cubital tunnel release.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the University of Rochester Center for Integrated Research Computing for providing computational resources used in this study.

Footnotes

The institution of one author (CPT) has received, during the study period, funding from the National Institutes of Health. The institution of one author (DTS) has received, during the study period, funding from the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand and the University of Rochester. One author (CPT) has received payment from the National Institutes of Health, Brown University, and Boston University. One author (WCH) has received payment from the International Bone Research Association and is a participant on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Sonex Health.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This publication was produced from raw data purchased from or provided by the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH). However, the conclusions derived, and views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the conclusions or views of NYSDOH. NYSDOH, its employees, officers, and agents make no representation, warrant, or guarantee as to the accuracy, completeness, currency, or suitability of the information provided here.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board (study STUDY00002011).

This work was performed at the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA.

Contributor Information

Warren C. Hammert, Email: warren.hammert@duke.edu.

Aniruddh Mandalapu, Email: Aniruddh_Mandalapu@urmc.rochester.edu.

Caroline P. Thirukumaran, Email: caroline_thirukumaran@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

- 1.Boone S, Gelberman RH, Calfee RP. The management of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:1897-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camp CL, Ryan CB, Degen RM, Dines JS, Altchek DW, Werner BC. Risk factors for revision surgery following isolated ulnar nerve release at the cubital tunnel: a study of 25,977 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:710-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng C, Rodner CM. Associations between insurance type and the presentation of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaspar MP, Jacoby SM, Osterman AL, Kane PM. Risk factors predicting revision surgery after medial epicondylectomy for primary cubital tunnel syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:681-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodgins JL, Vitale M, Arons RR, Ahmad CS. Epidemiology of medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:729-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchinson DT, Sullivan R, Sinclair MK. Long-term reoperation rate for cubital tunnel syndrome: subcutaneous transposition versus in situ decompression. Hand (N Y). 2021;16:447-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izadpanah A, Gibbs C, Spinner RJ, Kakar S. Comparison of in situ versus subcutaneous versus submuscular transpositions in the management of McGowan Stage III cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand (N Y). 2021;16:45-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koziej M, Trybus M, Banach M, et al. Comparison of patient-reported outcome measurements and objective measurements after cubital tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:1171-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krogue JD, Aleem AW, Osei DA, Goldfarb CA, Calfee RP. Predictors of surgical revision after in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:634-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law TY, Hubbard ZS, Chieng LO, Chim HW. Trends in open and endoscopic cubital tunnel release in the Medicare patient population. Hand (N Y). 2017;12:408-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyman S, Jones EC, Bach PB, Peterson MGE, Marx RG. The association between hospital volume and total shoulder arthroplasty outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432:132-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin K, Du S, Sobottka SB, et al. Retractor-endoscopic nerve decompression in carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes: outcomes in a small series. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:361-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendelaar NHA, Hundepool CA, Hoogendam L, et al. Outcome of simple decompression of primary cubital tunnel syndrome based on patient-reported outcome measurements. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:247-256.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park KW, Boyer MI, Gelberman RH, Calfee RP, Stepan JG, Osei DA. Simultaneous bilateral versus staged bilateral carpal tunnel release: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:796-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers MJ, Agwuncha CC, Kazmers NH. Patient expectations for symptomatic improvement before cubital tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Said J, Van Nest D, Foltz C, Ilyas A. Ulnar nerve in situ decompression versus transposition for idiopathic cubital tunnel syndrome: an updated meta-analysis. J Hand Microsurg. 2019;11:18-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smit JA, Hu Y, Brohet RM, van Rijssen AL. Identifying risk factors for recurrence after cubital tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. Published online February 17, 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stagg V. ELIXHAUSER: Stata module to calculate Elixhauser index of comorbidity. 2015: Statistical Software Components S458077, Boston Co. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staples JR, Calfee R. Cubital tunnel syndrome: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:e215-e224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai T, Chen I, Majd ME, Lim B. Cubital tunnel release with endoscopic assistance: results of a new technique. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24:21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural-urban continuum codes. 2020. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx. Accessed February 23, 2022.

- 23.Van Nest D, Ilyas AM. Rates of revision surgery following in situ decompression versus anterior transposition for the treatment of idiopathic cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Microsurg. 2020;12:S28-S32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeoman TFM, Stirling PHC, Lowdon A, Jenkins PJ, McEachan JE. Patient-reported outcomes after in situ cubital tunnel decompression: a report in 77 patients. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2020;45:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, Earp BE, Blazar P. Rates of complications and secondary surgeries after in situ cubital tunnel release compared with ulnar nerve transposition: a retrospective review. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42:294.e1-294.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.