Abstract

Background

Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue (TPE) is the causative agent of human yaws. Yaws is currently reported in 13 endemic countries in Africa, southern Asia, and the Pacific region. During the mid-20th century, a first yaws eradication effort resulted in a global 95% drop in yaws prevalence. The lack of continued surveillance has led to the resurgence of yaws. The disease was believed to have no animal reservoirs, which supported the development of a currently ongoing second yaws eradication campaign. Concomitantly, genetic evidence started to show that TPE strains naturally infect nonhuman primates (NHPs) in sub-Saharan Africa. In our current study we tested hypothesis that NHP- and human-infecting TPE strains differ in the previously unknown parts of the genomes.

Methodology/Principal findings

In this study, we determined complete (finished) genomes of ten TPE isolates that originated from NHPs and compared them to TPE whole-genome sequences from human yaws patients. We performed an in-depth analysis of TPE genomes to determine if any consistent genomic differences are present between TPE genomes of human and NHP origin. We were able to resolve previously undetermined TPE chromosomal regions (sequencing gaps) that prevented us from making a conclusion regarding the sequence identity of TPE genomes from NHPs and humans. The comparison among finished genome sequences revealed no consistent differences between human and NHP TPE genomes.

Conclusion/Significance

Our data show that NHPs are infected with strains that are not only similar to the strains infecting humans but are genomically indistinguishable from them. Although interspecies transmission in NHPs is a rare event and evidence for current spillover events is missing, the existence of the yaws bacterium in NHPs is demonstrated. While the low risk of spillover supports the current yaws treatment campaign, it is of importance to continue yaws surveillance in areas where NHPs are naturally infected with TPE even if yaws is successfully eliminated in humans.

Author summary

In this study, we focused on yaws, a neglected tropical disease, and its causative agent, bacterium Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue (TPE). Yaws is currently reported in 13 endemic countries in Africa, southern Asia, and the Pacific region. It predominantly infects children and causes papilloma, ulcers and, if untreated, progresses into disfiguring deformation of the bone and cartilage. The second yaws eradication campaign, known as the Morges strategy, is currently ongoing and led by World Health Organization (WHO). There is, however, accumulating genetic evidence that TPE strains naturally infect nonhuman primates (NHPs) in Sub-Saharan Africa. Here, we wanted to find out if the most serious argument–nonhuman and human infecting strains of TPE differ in the previously unknown parts of their genomes, that was raised by the scientific community against nonhuman primates as a source for human yaws infection–is true. Our findings highlight NHPs as a possible source for human yaws, although in this study, we cannot provide insight into the functional aspects of spillover between humans and NHPs. Moreover, these findings underline that Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue can only be eliminated in humans, while the bacterium is still present in nonhuman primates in Sub-Saharan Africa. Whether or not human and nonhuman primate infecting strains are epidemiologically linked is subject to ongoing research. Nevertheless, our results highlight the need for a long-term yaws surveillance program in areas where the infected NHP populations occur.

Introduction

Treponema pallidum is the causative agent of syphilis (subsp. pallidum, TPA), bejel (subsp. endemicum, TEN), and human yaws (subsp. pertenue TPE) [1,2]. Compared to syphilis with its worldwide incidence, human yaws currently infects mainly children in 13 endemic countries in Africa, southern Asia, and the Pacific region [3]. The endemic character of yaws infection, the significant drop in prevalence after the first eradication campaign during the mid-20th century [3], the believed absence of a nonhuman reservoir, and new treatment options with a single oral dose of azithromycin [4–6] triggered the currently ongoing second yaws eradication campaign known as the Morges strategy [7].

Concomitantly with the introduction of the Morges strategy, genetic evidence started to show that TPE strains naturally infect some African nonhuman primates (NHPs) [8–14]. The work of Chuma et al. [15] provided genetic evidence of TPE infection in almost a hundred samples from six nonhuman primates species collected in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and the Republic of the Congo.

Despite increasing evidence of NHP TPE infection, one of the most important questions for yaws eradication is whether NHP infecting strains are genomically distinct to human infecting strains and if NHPs can serve as a potential source of human infection. The question remains unanswered, partly because we were short on complete genome sequences of TPE of NHP origin. Presently, there are only two complete NHP TPE genomes (strain Fribourg-Blanc [10] and strain LMNP-1 [11]); additionally, there are 14 draft genomes of varying quality [11,12,16]. In this study, we aimed to close this knowledge gap and therefore sequenced ten more genomes of NHP origin and finalized eight of them, lifting the total number of available complete genomes of NHP TPE to a total of ten, and compared all ten NHP TPE genomes to the eight completed TPE genomes of human origin. We hypothesized that the NHP strains were not genetically distinct from the human strains.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

No live animals were sampled for this study. All NHP samples were selected from our previous studies [9,17], where the interested reader will also find the ethical statements and further details regarding DNA extraction methods. Samples collected included whole blood, genital swabs and skin tissue biopsies. Further information about the samples can be found in Results section. The selection of suitable samples from our collection followed a process of quality checks and selection for diversity based on (1) genetic diversity based on TP0488 and TP0548 sequencing, (2) the sampled NHP species, (3) the geographic origin of the sample, and (4) the available quality and amount of TPE DNA. Further details are shown in Fig 1 and described below in the downstream processing of DNA samples.

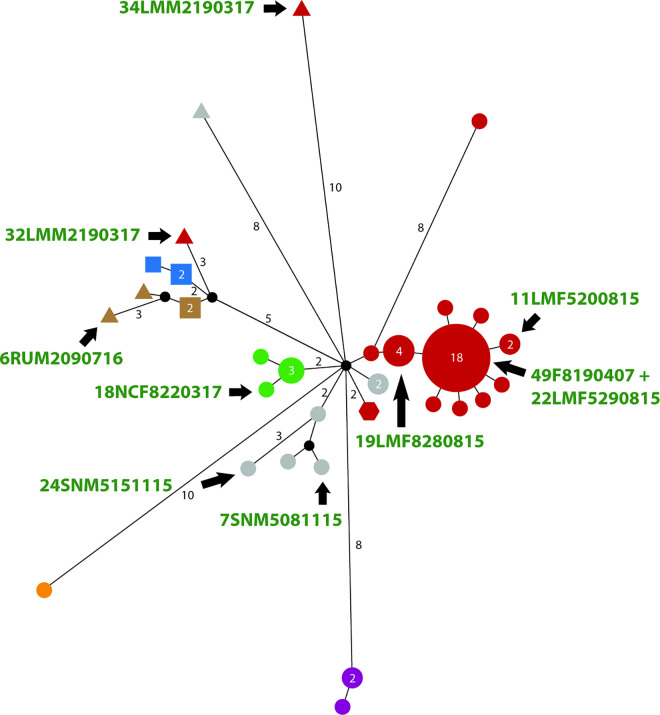

Fig 1. TPE strains of NHP origin from Tanzania chosen for whole-genome sequencing.

The figure is taken and modified from Chuma et al. [15]. Original figure (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-50779-9/figures/1) was licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Median-joining network using 1,773 bp–long concatemer of TP0488 and TP0548 loci from 57 Tanzanian NHPs samples. The number of nucleotide differences, when >1, are shown close to branches. Inferred allelic variants (median vectors) are shown as small black circles. If contiguous, indels were considered as single events only. The number of individual sequence variants, when > 1, are shown inside the circles and reflected by circle size. Color-code based on origin: blue–Issa Valley (n = 3), orange–Tarangire National Park (NP) (n = 1), brown–Ruaha NP (n = 4), red–Lake Manyara NP (n = 34), grey–Serengeti NP (n = 7), green–Ngorongoro Conservation Area (n = 5), violet–Gombe NP (n = 3). Geometric form according to the species: circle–Papio anubis (n = 46), square–Papio cynocephalus (n = 5), triangle–Chlorocebus pygerythrus (n = 5), hexagon–Cercopithecus mitis (n = 1). Sequenced samples are shown by black arrows. One of the arrows labels two strains (49F8190407 and 22LMF5290815).

All NHP TPE isolates analyzed in this study are shown in Table 1. Seven samples originated from olive baboons (Papio anubis), and three samples were collected from vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus). Of these, we were able to generate complete genome sequences from five P. anubis and three C. pygerythrus infecting strains.

Table 1. Genome regions in the assembled genomes that were checked and filled using Sanger sequencing.

| Strain | Number of gaps | Total length of gaps (nt) | Genome length (nt) | Percentage of genome finished by Sanger sequencing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6RUM2090716 | 8 | 5,073 | 1,140,284 | 0.44 |

| 7SNM5081115 | 9 | 6,156 | 1,139,594 | 0.54 |

| 18NCF8220317 | 14 | 11,387 | 1,139,654 | 1.00 |

| 19LMF8280815 | 27 | 11,851 | 1,139,879 | 1.04 |

| 22LMF5290815 | 12 | 6,426 | 1,140,667 | 0.56 |

| 24SNM5151115 | 14 | 10,542 | 1,140,433 | 0.92 |

| 32LMM2190317 | 14 | 9,864 | 1,140,113 | 0.87 |

| 34LMM2190317 | 20 | 9,898 | 1,140,506 | 0.87 |

Downstream processing of DNA samples

Based on our previous work, we used confirmed TPE positive DNA samples with moderate to high polymerase I (polA) gene copy numbers [9,17]. Subsequently, we checked DNA integrity by running a long-range PCR that targeted a 4,835 bp long region of the tprC gene using primers (ES-42F and TPI-11A-R) and previously published PCR conditions [18]. The subset of samples was then evaluated for their total DNA yield and diversity based on our multi-locus sequence typing study [15].

We selected samples representing different haplotypes and subsequently enriched the bacterial DNA using Looxter Enrichment Kits (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol, or the bacterial DNA was enriched using DpnI restriction enzyme [18]. After DNA-target enrichment, qPCR was performed to target the housekeeping gene c-myc, using the protocol described for baboon samples [9]. We used c-myc as a marker of the genomic (host) DNA content of the sample and used only those samples with a polA:c-myc ratio > 1:1,000 for whole-genome sequencing. Eventually, we were able to include samples from two different NHP species, Chlorocebus pygerythrus (vervet monkey) and Papio anubis (olive baboon), which had been collected in protected areas in Tanzania, i.e., Lake Manyara National Park (NP), Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Serengeti NP, and Ruaha NP. Further details on the samples are in Table 1.

At this point, we used different methods to generate the genomes. While five samples (6RUM2090716, 7SNM5081115, 22LMF5290815, 24SNM5151115, 49F8190407) had the target DNA enriched using hybridization capture for next-generation sequencing (NGS, myBaits, Arbor Biosciences, USA) (SK lab), the other five samples (18NCF8220317, 19LMF8280815, 32LMM2190317, 34LMM2190317, 11LMF5200815) were subject to whole genome amplification (WGA, DS lab) using REPLI-g Single Cell Kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) or REPLI-g Mini Kits (QIAGEN) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplified samples were purified using SPRISelect beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, USA).

Library preparation and in-solution capture

Samples that were not whole genome amplified were TPE DNA enriched using hybridization capture for targeted NGS (myBaits, Arbor Biosciences, Ann Arbor, USA). In general, we followed the method described in our previous publication [11]. In brief, we used the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina and followed the manufacturer’s guidance. We followed the protocol for inputs ≥ 100–500 ng DNA and targeted a fragment size of 300–700 bps during the enzymatic digest. Subsequently, fragments were adapter-ligated and size selected using AMPure XP beads according to the NEB protocol. Where appropriate, DNA concentration was measured using a Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The library was finalized through single index PCR enrichment of 15 μl adaptor-ligated DNA fragments using the Universal PCR primer (i5 Primer) in combination with the respective Index Primer (i7 Primer). The cycling conditions followed the recommendations provided by NEB. Next, PCR reactions were cleaned using AMPure XP beads following the standard protocol. Afterward, libraries were quality checked using a Bioanalyzer 2000 (Agilent, Palo Alto, USA) and quantified using the NEBNext Library Quant Kit for Illumina.

The capture of TPE DNA followed the myBaits Hybridization Capture for Targeted NGS Manual 4.0 using custom-made RNA baits (Arbor Biosciences, Ann Arbor, USA). Baits were designed based on 16 submitted TPE genomes (GenBank; human: CP002374.1, NC_016842.1, CP024750.1, NC_016848.1, NC_016843.1, CP024088.1, CP024089.1, and eight NHP: NC_021179.1 plus the genomes published by Knauf et al. [11]). Briefly, 80-nt baits with a 2x tiling density were designed after converting N-bases, in runs of ten or less, to Ts and removal of alignment gaps. Simple repeats were soft masked using RepeatMasker [19] and baits were collapsed at the 96% identity level. All bait sequences were BLASTed against the genomes of the olive baboon (Papio anubis, UCSC Genome Accession ID: GCF_000264685.3) and the African green monkey (Chlorocebus sabaeus; UCSC Genome Accession ID: GCA_000409795.2) with no hits against either genome.

Following library denaturation and adapter-blocking, target library molecules were allowed to hybridize with their complementary bait. Incubation times were set to 16 h and 30 min. Subsequently, bait-target hybrids were bound to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, which allowed us to separate the desired target DNA molecules from non-target DNA through three washing steps. This was followed by resuspension of the library in 30 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl, 0.05% TWEEN-20 solution (pH 8.0–8.5), and library amplification using KAPA HiFi Hot Start polymerase. Here, we followed the protocol and used 14 amplification cycles. After magnetic removal of the beads, the supernatant was purified using the SPRI cleanup method with NEBNext Sample Purification Beads (x 0.7; New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) according to NEB’s protocol. The SPRI cleanup product was 5-fold diluted in 0.1X TE buffer and quantified on a Qubit 3.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). In addition, 1 μl of the undiluted SPRI cleanup product was quality checked on the Bioanalyzer. Library quantification was performed using the qPCR NEBNext Quant Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, USA) following NEB’s recommended protocol. To increase the yield of target DNA, we reamplified the library from our first hybridization capture run using KAPA HiFi Hot Start polymerase in combination with Illumina adapter specific primers (sense 5’-AAT GAT ACG GCG ACC ACC GA-3’ and antisense 5’-CAA GCA GAA GAC GGC ATA CGA-3’). Cycling conditions were 2 min at 98°C followed by five cycles of 20 sec at 98°C, 30 sec at 60°C, and 45 sec at 72°C. The last step was a final phase of 5 min at 72°C. Next, the library product was quantified using Qubit 3.0 and again cleaned using the SPRI cleanup method as described previously. After quantification (Qubit 3.0) and a quality check on a Bioanalyzer, we initiated a second round of hybridization capturefollowing the above-described methods. The enriched 10 nM DNA libraries were pooled and sent out for sequencing.

DNA sequencing

Samples were processed using different platforms. Sample 22LMF5290815 was sequenced on an Illumina’s MiSeq, samples 19LMF8280815, 32LMM2190317, 34LMM2190317, and 18NCF8220317 on an Illumina’s HiSeq 2500, and samples 24SNM5151115, 7SNM5081115, 6RUM2090716, and 49F8190407 were sequenced by both MiSeq and HiSeq 2500 platforms. Sample 11LMF5200815 was amplified using the pooled segment genome sequencing (PSGS) method [20–22] and subsequently sequenced on a MiSeq. The sequencing platforms generated 150-bp (HiSeq 2500) or 250-bp (MiSeq) paired-end reads. We used the sequencing service of the Transcriptome and Genome Analysis Laboratory at the University Medical School Göttingen, Germany.

Bioinformatic analysis

The bioinformatic analysis of sequencing data was performed according to the workflow described previously [23] with several minor upgrades. The quality check of the raw reads was performed using FastQC (v0.11.5, [24]) and followed by pre-processed using Cutadapt (v2.6, [25]). The total set of pre-processed reads was mapped against the TPE strain LMNP-1 (GenBank CP021113.1) genome as a reference using the BWA MEM tool [26]/ BWA MEM2 (v2.2.1, [27]).

Post-processing of the mapping was performed with SAMtools (v1.9, [28]), Picard (v2.23.8, [29]), GATK (v3.7, [30]), and NGSUtils/bamutils (v0.5.9, [31]). Specifically, reads were realigned around indels, duplicated reads were removed, and low-quality mappings were filtered out using parameters for (1) mismatches (maximum of 5% of mismatches and maximum of 5 mismatches), (2) very short alignments (minimum of 35 bp mapping measured on the individual read), (3) soft-clipped bases (maximum of 5% of soft-clipped bases, no reads with hard-clipping), (4) mapping quality < 40 (MAPQ < 40), and (5) presence of singletons. These criteria were applied in order to get a high quality sequences and to eliminate the potential differences in the sequencing protocols used. MiSeq and HiSeq paired-reads were merged using SAMtools. The genome consensus sequence was determined based on at least three good-quality aligned reads using Picard tools.

To obtain improved broad coverage and more precise variant calling results, especially in the regions of paralogous genes and repeats, reference mapping was complemented by two de-novo assembly approaches, including (1) SPAdes [32] and (2) GFinisher [33]. As an input for de-novo assembly, unfiltered reads aligned to the reference genome were used. Contigs generated by 2 de-novo assembly approaches were mapped onto the consensus generated in the previous step (consensus based on short reads aligned to LMNP-1 genome by BWA) using minimap2 [34], and non-specific alignments (MAPQ < 10) were removed. Following this, contigs were mapped on consensus acquired by mapping of short reads. Consensus calling was then done to correct the consensus.

Variants that represented differences between the BWA-based consensus and the contigs from any of the de-novo assembly approaches were re-sequenced using Sanger sequencing. This also applied to regions covered by de-novo assembled contigs but not covered by reference mapping (coverage < 4). Furthermore, regions insufficiently covered by either short read mapping (coverage < 4) or de-novo assembly (coverage 0) were also re-sequenced.

For identification of the variants and insufficiently covered regions, SAMtools, bcftools [35], and BEDTools [36] were used.

For Sanger re-sequencing, specifically tailored amplicons were used. For quality control and evaluation of completeness of the assembly, each step of our described workflow was manually checked using IGV [37] and QUAST [38].

SRA data for genomes for extended phylogenetic tree were downloaded from NCBI. SRA Toolkit (v2.10.0, http://ncbi.github.io/sra-tools/) was used to extract reads from SRA files. The quality check of the raw reads was performed using FastQC (v0.11.5, [24]). To identify adapter sequences, BBMap was used (v38.42, [39]) and raw reads were preprocessed using Cutadapt (v2.6, [25]). Subsequently, reads were mapped to the reference genome (TPE strain LMNP-1 (GenBank CP021113.1)) and post-processing and filtering was performed as described above.

Genome gap filling

In each sequenced genome, gaps were identified and subsequently filled using PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing (Table 1).

Sequence gaps were amplified using TaKaRa PrimeSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase (Clontech, Mountain View, USA) in 40 μl PCR reactions. Details can be found in S1 Data–List of gaps + primers, where we present all sequenced regions and primer sequences. The reaction mix was made up of 8 μl GXL buffer, 3.2 μl dNTP mix (2.5 μM each), 3 μl DNA template, 0.8 μl PrimeStar GXL polymerase, 1.5 μl of each primer (10 μM) and 22 μl H2O. PCR was done using a Veriti 96-Well Fast Thermal Cycler with the following protocol: 94°C for 1 min, 8 cycles at 98°C for 10 s, 68°C (with TouchDown, temperature lowered 1°C after each cycle) for 15 s and 68°C for 6 min, 35 cycles at 98°C for 10 s, 61°C for 15 s, and 68°C for 6 min. The final extension was at 68°C for 7 min. In regions where nested PCR was applied, both steps were run under the above-described conditions. PCR products were checked for the correct fragment size on a 1% agarose gel. Subsequently, PCR products of the correct size were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, USA). In a final step, prior to sequencing, each amplicon sample was mixed with 5 μl primer (5 μM) of the respective sequencing primer, after which it was Sanger sequenced using the services of GATC Biotech AG (Konstanz, Germany). The quality checks and analysis of the obtained sequences, as well as the final construction of the respective TPE genome, was done using SeqMan NGen (DNASTAR, Madison, USA). Again, using the LMNP-1 (CP021113.1) strain of the TPE genome as a reference.

Sequence determination of arp (TP0433), TP0470, and rrn operons

The number of repeats in the acid-repeat protein (arp) gene (TP0433) and in TP0470 gene was determined by separate PCR amplification using three sets of primers (Table 2) for arp, and Bab32-LinOutL 5’ -ACC GCT ACA AAG AGG ATA GG-3’ and Bab32-LinOutR 5’ -GCT CTT TCT TTG TGC GTA GA-3’ for TP0470. All reactions used 0.8 μl TaKaRa PrimeSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase, 8 μl 5x PS GXL buffer, 3.2 μl dNTP Mix, 1.5 μl of each primer (10μM), 22 μl RNase free H2O, and 3 μl DNA template. PCR was run using a Veriti 96-Well Fast Thermal Cycler with the following protocol: 94°C for 1 min, 8 cycles at 98°C for 10 s, 68°C (with TouchDown, temperature lowered 1°C after each cycle) for 15 s and 68°C for 1 min, 35 cycles at 98°C for 10s, 61°C for 15 s as well as 68°C for 1 min. PCR ended with a final extension step at 68°C for 7 min. The resulting DNA segments were checked for correct size on 1% agarose gel, and Sanger sequenced.

Table 2. Primers used for arp sequencing.

| Primer name | Primer sequence | Samples |

|---|---|---|

| 32Brep-F1 | 5‘-CGT TTG GTT TCC CCT TTG TC | 22LMF5290815, 24SNM5151115, 6RUM2090716, 7SNM5081115 |

| 32Brep-R1 | 5‘-CAT ACG AAG CAG CCA TCC CAC | |

| Bab29-LinOutL | 5‘-ACA CTG CTG TTG AAA TTA GC | 19LMF8280815, 18NCF8220317 |

| Bab29-LinOutR | 5‘-GAG CAT TGT CCA CCG TTA CG | |

| TP_arp_S_Harper2008 | 5‘-AGC GTG ATC CTC TGT CAT CC | 32LMM2190317, 34LMM2190317 |

| TP_arp_AS_Harper2008 | 5‘-TTG GGA GCT GAG TTG GAA AC |

For the samples 22LMF5290815, 24SNM5151115, and 6RUM2090716, Sanger sequencing reads were not long enough to accurately determine the number of repeats in the TP0470 gene. We, therefore, sequenced those arp products using MinION Oxford Nanopore Technologies (Oxford, UK). The sequencing library was prepared using the 1D Native barcoding genomic DNA protocol with EXP-NBD103 and SQK-LSK108 kits (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) according to the manufactures’ instructions. The prepared library was loaded to the Nanopore MinION Spoton flow cell (FLO-MIN106D, version R9) and sequenced for 48 hours. Base-calling and barcoding were done by Guppy (v4.4.1, Oxford Nanopore Technologies), using the high accuracy base-calling mode and q-score 7. Minimap2 (v2.17, [34]) was used to map reads to references; map reads of a known size (4–6kbp) were selected by SAMtools (v0.1.20, [28]) and Picard (v 2.8.1, [29]). The 50 longest reads were evaluated in the EditSeq program (Lasergene DNASTAR, Madison, USA), and the most frequent variant was used to determine the number of repeats. The position of rrn spacer patterns in all samples was determined using the previously published approach [21].

Data analysis

Statistical analyses of the numbers of repeats in genes TP0304, TP0433 (arp), TP0470 and TP0967, and IGR TP0488-9 were done using R (R Core Team [40]; Vienna, Austria) (packages DescTools [41] and dplyr [42]). Scatter plots were constructed using Prism5 (GraphPad, San Diego, USA), and the number of repeats in these genes was checked for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test (if p-values were > 0.05, we assumed normality), and p-values were determined using the Unpaired Two-sample t-test for data with a normal distribution or Mann-Whitney test for data without a normal distribution (difference was considered statistically significant if the p-value was < 0.05).

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGAX (v.10.2.6, [43]) with 1000 replicates. Genes identified as those with positively selected sequences [44] were removed from the whole genome sequence alignments, as well as all tpr genes, TP0433 (arp), TP0470, and both t0012 and t0015 (tRNA-Ala and tRNA-Ile), due to the previously published presence of recombination and/or positive selections. We inferred the evolutionary history through the application of the Maximum Likelihood method using the Tamura-Nei model [45]. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Tamura-Nei model and then selecting the topology with superior log-likelihood values. All positions containing gaps and missing data were consequently removed from the analysis. We also constructed a phylogenetic tree using draft genome sequences of strains 11LMF5200815 and 49F8190407, as well as from other published TPE genomes of NHP from Cote d’Ivoire [13], Cote d’Ivoire, Gambia, Senegal, and Tanzania [11] and from Senegal [12], and from TPE of human origin, i.e., from Lihir Island [46], Solomon Islands [47], and Liberia [48]. Genome sequences were produced from available SRA data using the same approach as described above using Bioinformatic analysis, with the exception of genomes originating from study of Mediannikov (2020) [12], where only draft assemblies are publicly available. From the available 68 draft genome sequences, 59 had a broad genome length coverage (of more than 3 reads) of 92.8% or higher. Sequences with less coverage were not used for the construction of phylogenetic trees.

Pseudogenes were analyzed in all TPE genes with full genome sequences (n = 18). The following criteria were applied: (1) predicted gene length longer than 415 bp to avoid misannotated open reading frames, (2) nucleotide variants in the first 100 bps leading to frameshift or premature stop codons were not considered due to the presence of a possible downstream start of the gene, and (3) nucleotide variants in the last quarter of the gene were not considered due to the possibility of a variable C-terminus of the mature protein.

Whole genome sequences were annotated using Geneious Prime v2021.1.1 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

Results

Characteristics of TPE isolates and whole-genome sequencing parameters

All NHP TPE strains analyzed in this study are shown in Table 3. Seven samples originated from Papio anubis, and three samples were collected from Chlorocebus pygerythrus. Of these, we were able to generate complete genome sequences from five P. anubis and three C. pygerythrus infecting strains.

Table 3. Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue (TPE) strains analyzed in this study.

| TPE isolate | Source | Sex | Origin | Year of isolation | gDNA concentration (ng/μl) | No. of TPE copies per μl | DNA enrichment method | No. of mapped reads | Genome coverage (%) | Average coverage | Complete finished genome sequence (% of genome covered) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6RUM2090716 | C. pygerythrus | M | RNP | 2016 | 1682 | nd | Looxtera | 17,006,986 | 98.65 | 2274x | Yes (100%) |

| 7SNM5081115 | P. anubis | M | SNP | 2015 | 1659 | nd | Looxter | 978,074 | 98.47 | 131x | Yes (100%) |

| 11LMF5200815 | P. anubis | F | LMNP | 2015 | 564 | 5.41E+03 | DpnIb, PSGSc | 24224732 | 92.90 | 3185x | No (93%) |

| 18NCF8220317 | P. anubis | F | NCA | 2017 | 209 | 6.50E+03 | DpnI | 1,340,910 | 98.58 | 157x | Yes (100%) |

| 19LMF8280815 | P. anubis | F | LMNP | 2015 | 1002 | 4.17E+04 | DpnI | 185,342 | 98.08 | 19x | Yes (100%) |

| 22LMF5290815 | P. anubis | F | LMNP | 2015 | 1652 | nd | Looxter | 554,102 | 98.54 | 122x | Yes (100%) |

| 24SNM5151115 | P. anubis | M | SNP | 2015 | 1586 | nd | Looxter | 1,008,626 | 98.34 | 135x | Yes (100%) |

| 32LMM2190317 | C. pygerythrus | M | LMNP | 2017 | 233 | 1.47E+05 | DpnI | 3,756,864 | 98.58 | 435x | Yes (100%) |

| 34LMM2190317 | C. pygerythrus | M | LMNP | 2017 | 164 | 6.39E+05 | DpnI | 2,711,410 | 98.80 | 325x | Yes (100%) |

| 49F8190407 | P. anubis | F | LMNP | 2007 | 1681 | nd | Looxter | 225412 | 98.19 | 30x | No (98%) |

nd, not determined; M–male, F–female; SNP—Serengeti National Park, TZ; NCA—Ngorongoro Conservation Area, TZ; LMNP—Lake Manyara National Park, TZ; RNP—Ruaha National Park, TZ; GSNP—Gombe Stream National Park, TZ

a DNA enriched by LOOXTER Enrichment Kit (Analytik Jena, Germany)

b performed according to Grillová et al., [18]

All raw sequence read files can be found in NCBI under BioProject numbers PRJNA813752, PRJNA813753, PRJNA813756, PRJNA813757, PRJNA813758, PRJNA813760, PRJNA813762, PRJNA813764, PRJNA820556 and PRJNA820558. GenBank accession numbers for the eight complete annotated sequences can be found in S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features.

Comparison of TPE genomes of human and NHP origin

The genomes of TPE isolates infecting NHPs determined in this study were compared to available whole genome sequences of TPE of human origin. Eight human TPE genomes with complete genome sequences were available: strains Samoa D (CP002374), Gauthier (CP002376), and CDC-2 (CP002375) [49], strains CDC-2575 (CP020366) and Ghana-051 (CP020365) [50], strains Kampung Dalan K363 (CP024088) and Sei Geringging K403 (CP024089) [51], as well as strain CDC-1 (CP024750, this study). In addition, two previously completed whole-genome sequences originating from NHP infecting strains (strain Fribourg-Blanc, CP003902 [10] and strain LMNP-1, CP021113 [11]) were included.

The comparison of genomic features, including indels, pseudogenes, differences in gene alleles between humans and NHP TPE (S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features), and differences in the length of homopolymeric tracts are shown in Fig 2. Altogether, 13 genomic regions in TPE genomes of either NHP or human origin showed variants that were detected in two or more genomes (S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features). These differences included (1) different alleles of the tprC and tprD genes, (2) variants of rrn operons, (3) indels in TP0067, TP0136, TP0326, TP0462, and TP0548, and (4) the number of repeats in TP0304, TP0433, TP0470, IGR TP0488-489, and TP0967. Genetic differences found only in a single genome are shown in S2 Table.

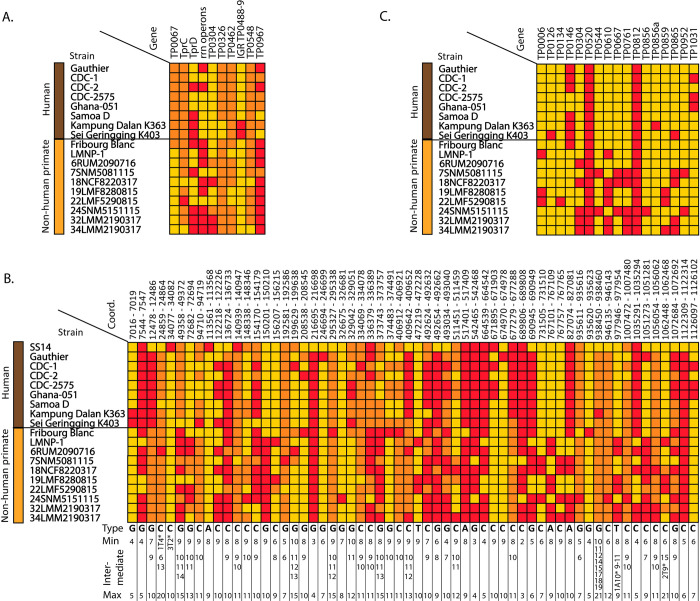

Fig 2. Comparison of human and NHP strains.

Samples of human and NHP origin are marked in brown and yellow, respectively. (A) A comparison of genomic features between TPE of human and nonhuman primate origin. Only genomic regions showing similar differences and detected in two or more genomes are shown. For more details see S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features. Same color cells indicate the same sequence variant. For changes present only in one genome see S2 Table. (B) Differences in the length of homopolymeric tracts in the analyzed genomes. Coordinates correspond to the reference genome LMNP-1. The length of homopolymeric tracts was determined by the dominating variant in the sequencing reads of any given homopolymer. Homopolymeric tracts differing in the number of nucleotides in at least one genome are shown. For comparison, the length of homopolymeric tracts in the SS14 genome is shown. The maximum (red) and minimum (yellow) number of nucleotides are shown, with all values in between shown in orange. All length values are listed at the bottom of the figure. Exact numbers of nucleotides in homopolymeric tracts for each genome that have three or more variants are shown in S1 Fig. *Homopolymers with nucleotide substitution. 1T4 = CTC CCC, 3T2 = CCC TCC, 1A10 = CAC CCC CCC CCC, 2T9 = CCT CCC CCC CCC. (C) Pseudogenes identified in the set of analyzed TPE strains/isolates. Identified pseudogenes are highlighted in red while yellow indicates functional genes.

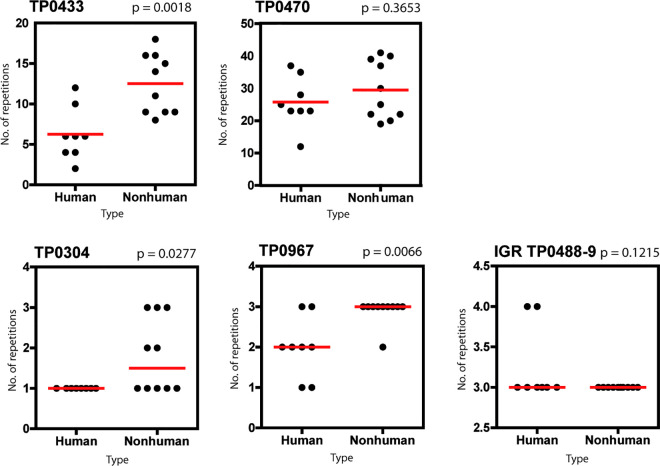

No genomic differences reflecting the origin of TPE strains (either NHP or human) were found between the analyzed genomes. However, most of the TPE genomes of NHP origin, except for the Fribourg-Blanc genome, contained a 9 nt-long deletion in the repeat-containing region of the TP0067 gene. The mean (or median) number of repeats in genes TP0304, TP0433 (arp), TP0470, and TP0967 were higher in TPE strains that infect NHPs, and this difference was statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) for the TP0304, TP0433, and TP0967 genes (Fig 3). The number of arp repeats in TPE genomes from NHPs had higher average lengths (14.3 repeats), while the human TPE strains analyzed to date contained, on average, 6.25 repeats per arp gene (S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features). The difference in the number of repeats in TP0470 and intergenic region (IGR) TP0488-489 was not statistically significant between TPE isolates from humans and NHPs.

Fig 3. The number of repeats in genes TP0304, TP0433 (arp), TP0470, TP0967, and IGR TP0488-9 showed differences between TPE strains of human and NHP origin.

The mean values (marked by red lines) for TP0433 and TP0470 genes with normal data distribution were 6.25 and 12.5 and 25.8 and 29.5 for TPE isolates from humans and NHPs, respectively. The median values (marked by red lines) for genes TP0304, TP0967, and IGR TP0488-9, which did not have normal data distribution, were 1 and 1.5, 2 and 3 and 3 and 3, for TPE isolates from humans and NHPs, respectively. The differences in the TP0470 and IGR TP0488-9 genes were not statistically significant (p-value > 0.05). The p-values are shown at the top of column scatter plots for individual TP0304, TP0433, TP0470, TP0967, and IGR TP0488-9 genes.

In addition to the number of repeats, differences in the length of homopolymeric tracts were also analyzed (Fig 2B). There were no differences between TPE strains that infect humans or those that infect NHPs, with the single exception of a difference in the homopolymeric tract within the TP0012 gene between coordinates 12,478–12,486. In this homopolymer, all TPE strains from NHPs differed from human TPE in their homopolymeric tract lengths (Fig 2B).

Among the set of analyzed TPE strains/isolates with finished genome sequences, 17 pseudogenes were identified (Fig 2C) based on criteria specified in the Material and Methods section. Pseudogenes in TP0520 and TP0812 were found in all genomes. Although the analyzed genomes of TPE from NHP origin showed more frequent occurrences of pseudogenes, no consistent differences in the presence of pseudogenes were found between TPE genomes from NHPs and humans. The Fribourg-Blanc isolate showed the presence of the same number of pseudogenes as that found in TPE strains of human origin.

Analyses of tpr genes

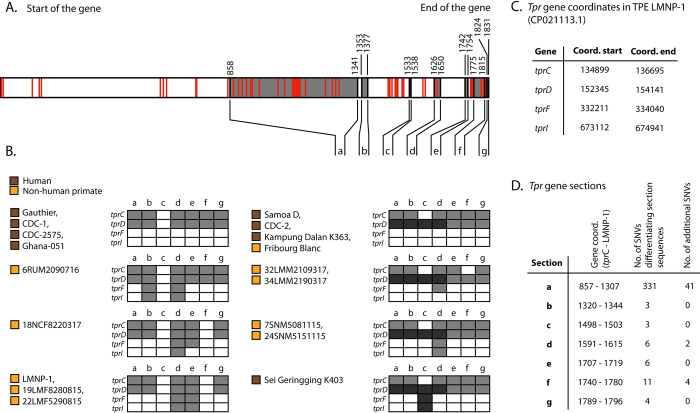

The number of variable nucleotide sites ranged between two to five in individual tprA, B, E, G, H, J, and L genes. The tprK gene contained intrastrain heterogeneity sites [52] and was not analyzed in this study. The remaining tprC, D, F, and I genes had considerably higher variability compared to tprA, B, E, G, H, J, and L genes in TPE genomes of both human and NHP origin. The tprD gene showed the presence of two alleles (tprD and tprD2; S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features) with several single nucleotide variants (SNVs) found predominantly within the tprD allele (S2 Fig). The tprC, D, F, and I genes were found to contain a modular structure with seven identifiable sections (a–g) (Fig 4), as previously suggested by Strouhal et al. [51]. Each section was defined based on nucleotide sequences differing in three and more positions. The number of nucleotide differences was 331 for section a, 3 for section b, 3 for section c, 6 for section d, 6 for section e, 11 for section f, and 4 for section g. The number of SNVs present inside each section (irrespective of section pattern) was 41, 0, 0, 2, 0, 4, and 0, in sections a-g, respectively. Another 74 SNVs were located outside of the sections a–g. Each section was present in two variants, except for sections a, b, and d, which were present in three variants. Different sequence variants of the sections combined into different patterns (n = 8) of the tprC, D, F, and I genes in different TPE isolates. Generally, tprF and tprI genes in TPE isolated from NHPs showed more variability (Fig 4) and combined more different tpr sections. Altogether, more patterns, including all tprC, D, F, and I genes, were detected in NHPs (n = 6) compared to patterns in TPE of human origin (n = 3). One combination pattern was present in both groups. No consistent patterns were observed to differentiate between the two groups. The Fribourg-Blanc isolate resembles human TPE strains (CDC-2, Samoa D, Kampung Dalan K363).

Fig 4. Sequence analysis of tprC, D, F, and I genes.

A. Visualization of the full-length tprC, D, F, and I genes, including gene sequences marked as sections (a–g, shown in grey, seven in total). Each section was defined as a DNA region containing two or more nucleotide sequences that differ in three and more positions. Black lines denote positions of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) at the start and at the end of each section. Single nucleotide variants not following the pattern of the section detected within and outside sections are shown as red lines. B. Modular structure of tprC, D, F, and I genes. White and grey show the two different versions of the DNA regions. Dark grey represents the tprD2 allele. Different sequence versions of the sections are combined into different patterns of the tprC, D, F, and I genes in different TPE isolates. In general, the tprF and tprI genes in TPE isolated from NHPs show more variability in combining different versions of the sections compared to TPE of human origin. The Fribourg-Blanc isolate, CDC-2, Samoa D, and Kampung Dalan K363 have identical modular structures of tprC, D, F, and I. C. Coordinates of the tprC, D, F, and I genes with respect to the LMNP-1 reference. D. Section coordinates according to tprC gene coordinates of LMNP-1 reference and the number of SNVs differentiating sections as well as the number of additional SNVs.

Phylogenomic analysis

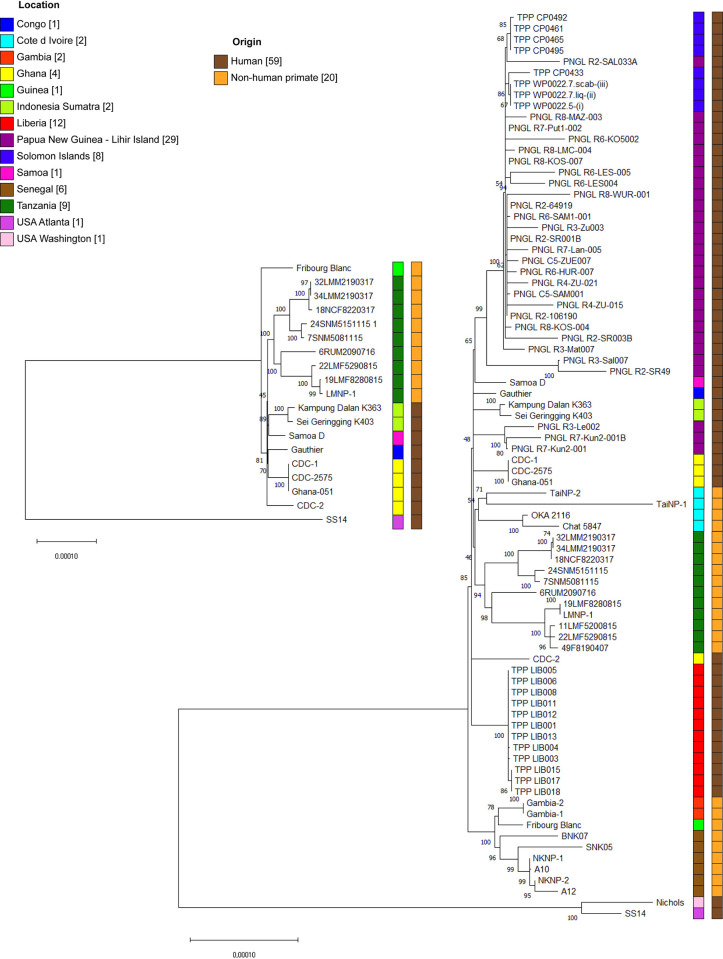

To assess the phylogenetic relatedness of the analyzed TPE genomes, recombinant and positively selected regions identified in a previous study on TPE genomes [44] were removed, as well as all tpr genes, TP0433 (arp), TP0470, and both t0012 and t0015 (tRNA-Ala and tRNA-Ile), and the remaining sequences were aligned and used for construction of a phylogenomic tree (Fig 5). TPE strains of human and NHP origin cluster into distinct groups (although with low bootstrap support for the human clade), while the Fribourg-Blanc strain falls as a sister lineage to all other TPE strains. Although this tree shows separation by host origin, it contains a limited subset of genomes and all but one NHP strain originate from Tanzania. We extended our analysis by including TPE draft genome sequences from other studies to better generate a broader phylogenetic picture. The draft genome sequence-based tree shows a clustering based on geographical origin and not based on host species. In this tree, the Fribourg-Blanc strain clustered with other samples from West Africa. This finding is in agreement with previous studies [11,13,46,48].

Fig 5. Phylogenetic analysis of TPE genomes of human and NHP origin.

The phylogenetic relatedness of TPE genomes determined for complete (left tree) and draft (right tree) genomes. Draft genomes from other studies were used [11–13,46–48]. Draft genomes with more than 83,7% coverage were used for tree construction. TPA strains SS14 and Nichols were used as outgroups. For more details see S1 Data–Overview of strains (phylogeny). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model [45]. The bootstrap values of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were deleted. There was a total of 1,092,985 and 651,557 positions in the tree containing 19 and 80 nucleotide sequences, respectively, with 1561 and 4311 variable sites. The color legend next to the trees marks the geographical origin of the samples. Human and nonhuman primate origin is displayed using brown and yellow color, respectively. TPE genomes predominantly cluster relative to the geographical origin.

Discussion

Despite the fact that our study is limited in extent, it contributes additional eight complete and two draft genome sequences of NHP infecting TPE isolates from Tanzania to the current set of available TPE genomes. The selected samples were not randomly chosen but instead represented genetically divergent samples isolated from different NHP species and geographical areas (Fig 1) [15]. Since isolates from the same geographical region often show genetic relatedness (Fig 5), preselection of samples based on multi-locus sequence typing allowed us to overcome the risk of sequencing clonal isolates [46–48,53].

In this study, the intrastrain heterogeneity analyzing variability within the infecting treponemal population was not determined. Instead, we used the most prevalent nucleotide variants at any given position.

We showed that TPE genomes isolated from NHPs do not show consistent genomic differences from TPE strains that infect humans. This indicates that current NHP TPE strains are not only similar [11] but belong to the same subspecies as human TPE. Previous studies have supported this finding based on a single complete genome [10,11] or draft genomes [11,12] as well as MLST [15]. In our study, we present several whole genome TPE sequences of NHPs that do not show consistent differences compared to human TPE strains. This finding indicates that these strains are indeed the same subspecies. It includes the largest dataset of primate (human and nonhuman) closed TPE genomes to date–eight TPE genomes of human origin [21,50,51] (CP024750) and ten TPE whole-genome sequences of NHP origin from Africa [10,11]. The number of investigated genomes is still limited, plus all samples originate from Tanzania. However, we are confident that this does not affect our main statement, which is that NHP infecting strains are not genetically distant from human-infecting TPE strains. All genomes included into the study have the same genetic characteristics.

We were able to resolve previously undetermined TPE chromosomal regions (sequencing gaps) that prevented us from making a conclusion regarding the sequence identity of TPE genomes from NHPs and humans since we were not able to rule out the potential existence of substantial differences in the previously unknown parts of the genome. While strains with different characteristics can exist in unsampled datasets, identification of strains that do not differ from strains infecting humans proves that NHP populations can serve as a potential reservoir for such infection at least in the studied area. This is further supported by the fact that, while highly unethical, experimental inoculation of the Fribourg-Blanc strain into human skin resulted in a viable yaws infection [54]. Likewise, experimental inoculation of NHPs with TPE of human origin resulted in typical yaws skin lesions [55].

Our current study seems to complicate yaws eradication efforts, in particular, because of the high TPE infection rates among African NHPs [11,12,15,56] where in some of them, clinical and genomic evidence of yaws-like lesions has been demonstrated [14]. However, the risk of a zoonotic spillover is difficult to proof. It is still unclear whether human and nonhuman primate infecting strains are epidemiologically linked. If, for example, NHPs frequently functioned as a source for human infection, we would see infections in children in Tanzania, which we demonstrated is not the case [57]. The reason that TPE strains from NHPs cluster separately from current human TPE of human origin (Fig 5) is also supported by previous studies [11,12,15] and is likely the effect of the different geographic sampling locations; however, it could also indicate infrequent spillovers between humans and NHPs. Similar genome characteristics (S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features, Fig 4) between the Fribourg-Blanc (of NHP origin) and human CDC-2 strains suggest that such transfers have happened in the past. For NHP TPE strains, the interspecies transmission of TPE has already been suggested [15]. So far, sample sizes from any geographic region are insufficient, and future studies are warranted to collect more TPE samples from areas where infected humans and NHPs coexist.

As predicted earlier [52] and shown in this study, the tprC, D, F, and I genes showed a modular structure and were found to be more genetically diverse in TPE of NHP origin than the human TPE strains. The 3’ gene half encodes for a C-terminal domain MOSPC having a β-barrel structure residing in the outer membrane [58]. A possible explanation for the observed higher variability among TPE in NHPs could be that (wild) NHPs are generally not treated for infection, which favors natural selection of new variants of outer membrane proteins while human infections are more often treated with antibiotics.

Significantly higher numbers of repeats in the arp gene (TP0433) among the NHP isolates were found compared to human TPE strains. We showed that NHP TPE has an average length of 14.3 arp repeats, which is similar to the most frequent number of repeats in human TPA strains [59]. Moreover, while there is an inversed correlation between the number of detected repeats in the arp and TP0470 genes, as shown by linear regression analysis among human TPE strains [60], no such correlation was observed for NHP TPE; interestingly, this is also seen in human TPA (syphilis). While the reason for these observations is unclear and could potentially reflect sexual transmission [61], the difference in the number of arp repeats, and any other repeat regions (S1 Data–Comparison of genomic features) found in the genome, should not be considered as the main difference between human and NHP TPE genomes. This is because the extension and shortening of sequences containing repetitive motifs are one of the most frequent changes observed in pathogenic treponemes and other bacteria [62]. We should also not forget that the number of repeats is highly mutable, as seen in human syphilis cases with two parallel samples collected at the same time (skin swab and whole blood sample) that showed two different arp repeat numbers [63]. The number of arp repeats, therefore, represents a variable and fast adaptation to a particular host, transmission route, and/or climate conditions.

Conclusion

Our detailed analysis of TPE genomes revealed no consistent genomic differences between TPE genomes from human and NHP infections, thus demonstrating that NHP TPE isolates are not genomically distinct from strains causing human yaws. Although interspecies transmission seems to be rare and evidence for current spillover events are missing, the existence of TPE in NHPs is clearly demonstrated. There is no doubt that the endemic character of human yaws infection together with the presence of effective single peroral azithromycin therapy [4,64,65] promised successful and straightforward yaws elimination from the human population [7]. Full eradication of TPE would, however, require treatment of African NHPs, which cannot be realistically achieved. The low risk of spillover supports the current yaws treatment campaign, which under no circumstances should be stopped. Instead, yaws eradication in humans must be followed by continuous disease surveillance in areas where NHP infection is known to be present.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(TIF)

The major difference in variable positions differentiated tprD and tprD2 alleles. Only variable positions are shown. Deletions are shown in white, variants in dark grey, and difference in the nucleotide variant is shown in black.

(TIF)

List of sequencing gaps and primers used for gap filling. Comparison of genomic features. A comparison of genomic features between TPE of human and nonhuman primate origin. Only genomic regions showing similar differences from other genomes and detected in two or more genomes are shown. Indels and sequence differences found only in single genomes are not displayed. Shaded cells indicate the same sequence variant. Overview of strains (phylogeny). Details of the strains used for phylogenetic analysis.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

Computational resources were supplied by the project “e-Infrastruktura CZ” (e-INFRA LM2018140) provided within the program Projects of Large Research, Development, and Innovations Infrastructures. We thank Thomas Secrest (Secrest Editing, Ltd.) for his assistance with the English revision of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All raw sequence read files can be found in NCBI under BioProject numbers PRJNA813752, PRJNA813753, PRJNA813756, PRJNA813757, PRJNA813758, PRJNA813760, PRJNA813762, PRJNA813764, PRJNA820556 and PRJNA820558. GenBank accession numbers for the eight complete annotated sequences can be found in S1 Data – Comparison of genomic features.

Funding Statement

The work was partly funded by the National Institute of Virology and Bacteriology (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5103, Funded by the European Union - Next Generation EU, https://next-generation-eu.europa.eu/) to DS. The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, https://www.dfg.de/en/): KN1097/3-1 and KN1097/4-1 (SK), and RO3055/2-1 (CR). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lukehart SA, Giacani L. When Is Syphilis Not Syphilis? Or Is It? Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41: 554–555. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitjà O, Asiedu K, Mabey D. Yaws. The Lancet. 2013;381: 763–773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asiedu K, Fitzpatrick C, Jannin J. Eradication of Yaws: Historical Efforts and Achieving WHO’s 2020 Target. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8: e3016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitjà O, Houinei W, Moses P, Kapa A, Paru R, Hays R, et al. Mass treatment with single-dose azithromycin for yaws. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 703–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitjà O, González-Beiras C, Godornes C, Kolmau R, Houinei W, Abel H, et al. Effectiveness of single-dose azithromycin to treat latent yaws: a longitudinal comparative cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5: e1268–e1274. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30388-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John LN, Beiras CG, Houinei W, Medappa M, Sabok M, Kolmau R, et al. Trial of Three Rounds of Mass Azithromycin Administration for Yaws Eradication. N Engl J Med. 2022;386: 47–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organisation. Eradication of yaws—the Morges strategy. Releve Epidemiol Hebd. 2012;87: 189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper KN, Fyumagwa RD, Hoare R, Wambura PN, Coppenhaver DH, Sapolsky RM, et al. Treponema pallidum Infection in the Wild Baboons of East Africa: Distribution and Genetic Characterization of the Strains Responsible. PLOS ONE. 2012;7: e50882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knauf S, Batamuzi EK, Mlengeya T, Kilewo M, Lejora IAV, Nordhoff M, et al. Treponema Infection Associated With Genital Ulceration in Wild Baboons. Vet Pathol. 2012;49: 292–303. doi: 10.1177/0300985811402839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zobaníková M, Strouhal M, Mikalová L, Čejková D, Ambrožová L, Pospíšilová P, et al. Whole Genome Sequence of the Treponema Fribourg-Blanc: Unspecified Simian Isolate Is Highly Similar to the Yaws Subspecies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: e2172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knauf S, Gogarten JF, Schuenemann VJ, De Nys HM, Düx A, Strouhal M, et al. Nonhuman primates across sub-Saharan Africa are infected with the yaws bacterium Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7: 1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0156-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mediannikov O, Fenollar F, Davoust B, Amanzougaghene N, Lepidi H, Arzouni J-P, et al. Epidemic of venereal treponematosis in wild monkeys: a paradigm for syphilis origin. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;35: 100670. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mubemba B, Gogarten JF, Schuenemann VJ, Düx A, Lang A, Nowak K, et al. Geographically structured genomic diversity of non-human primate-infecting Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue. Microb Genomics. 2020;6: mgen000463. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mubemba B, Chanove E, Maetz-Rensing K, Gogarten JF, Duex A, Merkel K, et al. Yaws Disease Caused by Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue in Wild Chimpanzee, Guinea, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26: 1283–1286. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.191713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuma IS, Roos C, Atickem A, Bohm T, Anthony Collins D, Grillová L, et al. Strain diversity of Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue suggests rare interspecies transmission in African nonhuman primates. Sci Rep. 2019;9: 14243. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50779-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gogarten JF, Düx A, Schuenemann VJ, Nowak K, Boesch C, Wittig RM, et al. Tools for opening new chapters in the book of Treponema pallidum evolutionary history. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22: 916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuma IS, Batamuzi EK, Collins DA, Fyumagwa RD, Hallmaier-Wacker LK, Kazwala RR, et al. Widespread Treponema pallidum Infection in Nonhuman Primates, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24: 1002–1009. doi: 10.3201/eid2406.180037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grillová L, Oppelt J, Mikalová L, Nováková M, Giacani L, Niesnerová A, et al. Directly Sequenced Genomes of Contemporary Strains of Syphilis Reveal Recombination-Driven Diversity in Genes Encoding Predicted Surface-Exposed Antigens. Front Microbiol. 2019;10: 1691. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker. Available: http://repeatmasker.org [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinstock GM, Norris SJ, Sodergren E, and Šmajs D: Identification of virulence genes in silico: infectious disease genomics. In: Brogden KA, et al. (eds): Virulence Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogens, 3rd ed. ASM Press; 2000, Washington, D.C., pp. 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Čejková D, Zobaníková M, Pospíšilová P, Strouhal M, Mikalová L, Weinstock GM, et al. Structure of rrn operons in pathogenic non-cultivable treponemes: sequence but not genomic position of intergenic spacers correlates with classification of Treponema pallidum and Treponema paraluiscuniculi strains. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62: 196–207. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Štaudová B, Strouhal M, Zobaníková M, Čejková D, Fulton LL, Chen L, et al. Whole Genome Sequence of the Treponema pallidum subsp. endemicum Strain Bosnia A: The Genome Is Related to Yaws Treponemes but Contains Few Loci Similar to Syphilis Treponemes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8: e3261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grillová L, Giacani L, Mikalová L, Strouhal M, Strnadel R, Marra C, et al. Sequencing of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum from isolate UZ1974 using Anti-Treponemal Antibodies Enrichment: First complete whole genome sequence obtained directly from human clinical material. PLOS ONE. 2018;13: e0202619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrews S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

- 25.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal. 2011;17: 10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. ArXiv13033997 Q-Bio. 2013. [cited 15 Nov 2021]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Md Vasimuddin, Misra S, Li H, Aluru S. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. 2019 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS). 2019. pp. 314–324. doi: 10.1109/IPDPS.2019.00041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2009;25: 2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broad Institute. Picard Toolkit. 2019. Available: https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/

- 30.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20: 1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breese MR, Liu Y. NGSUtils: a software suite for analyzing and manipulating next-generation sequencing datasets. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2013;29: 494–496. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19: 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guizelini D, Raittz RT, Cruz LM, Souza EM, Steffens MBR, Pedrosa FO. GFinisher: a new strategy to refine and finish bacterial genome assemblies. Sci Rep. 2016;6: 34963. doi: 10.1038/srep34963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34: 3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2011;27: 2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26: 841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative Genomics Viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29: 24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29: 1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bushnell B. BBMap. 2017. Available: sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/

- 40.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2020. Available: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Signorell A, Aho K, Alfons A, Anderegg N, Aragon T, Arachchige C, et al. DescTools: Tools for Descriptive Statistics. 2021. Available: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DescTools [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, RStudio. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. 2021. Available: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35: 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maděránková D, Mikalová L, Strouhal M, Vadják Š, Kuklová I, Pospíšilová P, et al. Identification of positively selected genes in human pathogenic treponemes: Syphilis-, yaws-, and bejel-causing strains differ in sets of genes showing adaptive evolution. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13: e0007463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10: 512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beale MA, Noguera-Julian M, Godornes C, Casadellà M, González-Beiras C, Parera M, et al. Yaws re-emergence and bacterial drug resistance selection after mass administration of azithromycin: a genomic epidemiology investigation. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1: e263–e271. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30113-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marks M, Fookes M, Wagner J, Butcher R, Ghinai R, Sokana O, et al. Diagnostics for Yaws Eradication: Insights From Direct Next-Generation Sequencing of Cutaneous Strains of Treponema pallidum. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66: 818–824. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timothy JWS, Beale MA, Rogers E, Zaizay Z, Halliday KE, Mulbah T, et al. Epidemiologic and Genomic Reidentification of Yaws, Liberia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27: 1123–1132. doi: 10.3201/eid2704.204442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Čejková D, Zobaníková M, Chen L, Pospíšilová P, Strouhal M, Qin X, et al. Whole Genome Sequences of Three Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue Strains: Yaws and Syphilis Treponemes Differ in Less than 0.2% of the Genome Sequence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6: e1471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strouhal M, Mikalová L, Haviernik J, Knauf S, Bruisten S, Noordhoek GT, et al. Complete genome sequences of two strains of Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue from Indonesia: Modular structure of several treponemal genes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12: e0006867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strouhal M, Mikalová L, Havlíčková P, Tenti P, Čejková D, Rychlík I, et al. Complete genome sequences of two strains of Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue from Ghana, Africa: Identical genome sequences in samples isolated more than 7 years apart. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11: e0005894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giacani L, Brandt SL, Puray-Chavez M, Reid TB, Godornes C, Molini BJ, et al. Comparative Investigation of the Genomic Regions Involved in Antigenic Variation of the TprK Antigen among Treponemal Species, Subspecies, and Strains. J Bacteriol. 2012;194: 4208–4225. doi: 10.1128/JB.00863-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinto M, Borges V, Antelo M, Pinheiro M, Nunes A, Azevedo J, et al. Genome-scale analysis of the non-cultivable Treponema pallidum reveals extensive within-patient genetic variation. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2: 1–11. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sepetjian M, Guerraz FT, Salussola D, Thivolet J, Monier JC. [Contribution to the study of the treponeme isolated from monkeys by A. Fribourg-Blanc]. Bull World Health Organ. 1969;40: 141–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castellani A. Experimental Investigations on Framboesia Tropica (Yaws). Epidemiol Infect. 1907;7: 558–569. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400033520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zimmerman DM, Hardgrove EH, von Fricken ME, Kamau J, Chai D, Mutura S, et al. Endemicity of Yaws and Seroprevalence of Treponema pallidum Antibodies in Nonhuman Primates, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25: 2147–2149. doi: 10.3201/eid2511.190716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lubinza CKC, Lueert S, Hallmaier-Wacker LK, Ngadaya E, Chuma IS, Kazwala RR, et al. Serosurvey of Treponema pallidum infection among children with skin ulcers in the Tarangire-Manyara ecosystem, northern Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20: 392. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05105-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radolf JD, Kumar S. The Treponema pallidum Outer Membrane. In: Adler B, editor. Spirochete Biology: The Post Genomic Era. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 1–38. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng R-R, Wang AL, Li J, Tucker JD, Yin Y-P, Chen X-S. Molecular Typing of Treponema pallidum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5: e1273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Šmajs D, Strouhal M, Knauf S. Genetics of human and animal uncultivable treponemal pathogens. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;61: 92–107. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harper KN, Liu H, Ocampo PS, Steiner BM, Martin A, Levert K, et al. The sequence of the acidic repeat protein (arp) gene differentiates venereal from nonvenereal Treponema pallidum subspecies, and the gene has evolved under strong positive selection in the subspecies that causes syphilis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53: 322–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Avershina E, Rudi K. Dominant short repeated sequences in bacterial genomes. Genomics. 2015;105: 175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mikalová L, Pospíšilová P, Woznicová V, Kuklová I, Zákoucká H, Šmajs D. Comparison of CDC and sequence-based molecular typing of syphilis treponemes: tpr and arp loci are variable in multiple samples from the same patient. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13: 178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitjà O, Hays R, Ipai A, Penias M, Paru R, Fagaho D, et al. Single-dose azithromycin versus benzathine benzylpenicillin for treatment of yaws in children in Papua New Guinea: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial. The Lancet. 2012;379: 342–347. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61624-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abdulai AA, Agana-Nsiire P, Biney F, Kwakye-Maclean C, Kyei-Faried S, Amponsa-Achiano K, et al. Community-based mass treatment with azithromycin for the elimination of yaws in Ghana—Results of a pilot study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12: e0006303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(TIF)

The major difference in variable positions differentiated tprD and tprD2 alleles. Only variable positions are shown. Deletions are shown in white, variants in dark grey, and difference in the nucleotide variant is shown in black.

(TIF)

List of sequencing gaps and primers used for gap filling. Comparison of genomic features. A comparison of genomic features between TPE of human and nonhuman primate origin. Only genomic regions showing similar differences from other genomes and detected in two or more genomes are shown. Indels and sequence differences found only in single genomes are not displayed. Shaded cells indicate the same sequence variant. Overview of strains (phylogeny). Details of the strains used for phylogenetic analysis.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All raw sequence read files can be found in NCBI under BioProject numbers PRJNA813752, PRJNA813753, PRJNA813756, PRJNA813757, PRJNA813758, PRJNA813760, PRJNA813762, PRJNA813764, PRJNA820556 and PRJNA820558. GenBank accession numbers for the eight complete annotated sequences can be found in S1 Data – Comparison of genomic features.