Abstract

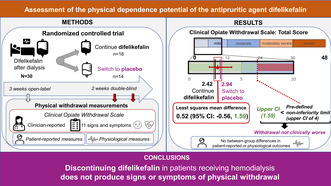

Difelikefalin is a selective kappa opioid receptor agonist approved for treating moderate‐to‐severe pruritus in adults undergoing hemodialysis (HD). Difelikefalin is not a controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act. This study assessed the potential for developing physical dependence on difelikefalin in patients undergoing HD. Eligible patients received open‐label difelikefalin after each dialysis session for 3 weeks before entering a 2‐week double‐blind phase, when they were randomized to either continue difelikefalin or to switch to receiving placebo. Signs of physical withdrawal were assessed using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS), several patient‐reported scales, and physiological measures. The primary end point was the between‐group difference in mean maximum COWS total scores during the double‐blind phase; the mean difference (placebo − difelikefalin) was compared against a predefined noninferiority limit (+4). Thirty‐five patients (57.1% male; 91.4% Black or African American; median [range] age 58 [28–77] years) were included, of which 30 were randomized (placebo, n = 14; difelikefalin, n = 16). The least squares mean difference in maximum COWS total scores was 0.52 (95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.56, 1.59). The upper CI limit (1.59) was below +4, indicating that patients who discontinued difelikefalin (placebo group) had similar withdrawal scores to patients who continued difelikefalin. Additional assessments supported the COWS results, showing no meaningful differences between groups in physiological measures or in patient‐reported measures of sleep or physical withdrawal. These results demonstrate that abruptly discontinuing chronic difelikefalin treatment in patients undergoing HD does not produce signs or symptoms of physical withdrawal.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

Difelikefalin is a selective kappa opioid receptor agonist approved for treating moderate‐to‐severe pruritus in adults undergoing hemodialysis (HD). Difelikefalin is not a controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

This randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study assessed whether difelikefalin has potential for physical dependence in patients undergoing HD.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

Abruptly discontinuing chronic difelikefalin treatment in HD patients did not produce signs or symptoms of physical withdrawal as assessed using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale, patient‐reported scales, and physiological measures.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

These findings suggest that there is a low likelihood of withdrawal when discontinuing chronic difelikefalin treatment in patients receiving HD. This supports the use of difelikefalin as an antipruritic treatment in this patient population.

INTRODUCTION

Difelikefalin (CR845) is a highly selective kappa opioid receptor (KOR) agonist developed for the treatment of chronic pruritic conditions. Difelikefalin was first approved in 2021 for moderate‐to‐severe chronic kidney disease‐associated pruritus (CKD‐aP) in adults undergoing hemodialysis (HD), based on significant reductions in pruritus intensity versus placebo in two phase III pivotal trials. 1 , 2 The compound's approved therapeutic use is by intravenous (i.v.) injection three times a week in dialysis clinics, administered at the end of each HD session. 3

Difelikefalin is a hydrophilic D‐amino acid peptide designed to have limited entry into the central nervous system, 4 distinguishing it from centrally active KOR agonists. In addition, difelikefalin has no relevant affinity for opioid receptors other than KOR, including the mu opioid receptor (MOR), delta opioid receptor, or nociceptin receptor. 4 , 5 It is therefore different from opioid analgesics that predominantly bind to MORs, including mixed KOR agonist/MOR partial agonists such as the drugs pentazocine and butorphanol that are Schedule IV controlled substances in the US. 4 Difelikefalin is not structurally related to controlled substances abused for psychoactive effects, such as opiates or stimulants, and as such it is not detected in drug abuse tests. It also has no identified off‐target activity and does not interact with known abuse‐related molecular targets. In line with these properties and in contrast with most opioid analgesics, i.v. difelikefalin does not induce respiratory depression, 6 has no significant abuse potential, 5 and is not a controlled substance in the Controlled Substances Act. 7

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) may require drugs to be assessed for potential physical dependence in humans as part of an assessment of their abuse potential and overall safety profile. 8 This assessment typically occurs at the conclusion of a phase II/III clinical interventional study through a monitored discontinuation period. Dedicated studies with fewer individuals may also be conducted to help confirm the assessment. The outcomes of these studies inform drug labeling on the risks associated with abrupt drug discontinuation and the possible need for tapered discontinuation. To date, no interventional studies conducted with difelikefalin have indicated potential for developing physical dependence upon abrupt treatment discontinuation after chronic administration. 1 , 9 As difelikefalin is a new class of KOR agonist, and because it is intended for chronic use, a dedicated clinical study was conducted specifically to assess the potential for developing physical dependence. Here, we present the results of this study.

METHODS

Study design

This was a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study conducted at five HD centers in the US between December 31, 2019 and June 11, 2020 (NCT05533008). The study consisted of: a screening phase, which contained a screening visit to determine patients' eligibility and a 1‐week baseline period to establish patients' baseline pruritus intensity, withdrawal symptoms, and physiological measures prior to treatment; a 3‐week open‐label phase, in which all patients received difelikefalin at the end of each dialysis session; a 2‐week randomized placebo‐controlled double‐blind phase, in which patients either continued to receive difelikefalin or were switched to receive placebo (abrupt treatment discontinuation) post‐dialysis; and a follow‐up visit 7 to 10 days following the end of treatment. During the course of the study, signs of potential physical withdrawal were assessed using an observer‐rated scale (the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale [COWS]), several subject‐reported scales, and physiological measures.

The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board (IntegReview IRB, US) and all study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation principles of Good Clinical Practice, and applicable local regulations. All patients provided their written informed consent.

Patient population

Eligible patients were 18–80 years of age, had a prescription dry body weight of 40–135 kg, had end‐stage renal disease, and were receiving HD three times per week for at least 3 months. Eligible patients also had to meet at least one of the following three criteria in the 3 months prior to screening: two single‐pool Kt/V measurements ≥1.2 on different dialysis days to assess the efficacy of the hemodialysis sessions; two urea reduction ratio measurements ≥65% on different dialysis days; or one single pool Kt/V measurement ≥1.2 and one urea reduction ratio measurement ≥65% on different dialysis days. Patients were excluded if they were taking or planning to take opioid medication at the time of enrollment; if female, were pregnant or nursing during any part of the study; if they had participated in a previous study of difelikefalin; or had a concomitant disease or history of a condition that might in the opinion of the investigator pose a risk to the patient or interfere with the completion of the study or validity of the study measurements.

Patients were excluded prior to the start of the open‐label phase if their COWS score was ≥8 (i.e., endorsement of signs assessed with COWS that are unrelated to treatment). Patients were excluded from the double‐blind phase if they had missed more than one dose of difelikefalin in the first 2 weeks of the open‐label phase, had missed any doses of difelikefalin during the last week of the open‐label phase, or had shown potential signs of withdrawal (COWS ≥8) during the open‐label phase. Concomitant treatment with stable doses of antihistamines, corticosteroids, gabapentin, and pregabalin was permitted if used at the time of the screening visit; the initiation of new antipruritic medications after the screening visit was prohibited.

Study conduct and assessments

Eligible patients who completed the 1‐week baseline period subsequently entered the open‐label phase and received i.v. difelikefalin at 0.5 mcg/kg (approved therapeutic dose; based on prescription dry body weight at screening) three times a week at the end of each dialysis session for 3 weeks. Patients who continued to meet the eligibility criteria were then randomized into the double‐blind phase in a 1:1 ratio to either continue to receive difelikefalin 0.5 mcg/kg or to receive placebo after each dialysis session, for 2 weeks. Patients were stratified before randomization according to whether they experienced moderate‐to‐severe itch at baseline, defined as at least one score during the 7‐day baseline period >4 on the Worst Itching Intensity Numerical Rating Scale (WI‐NRS; a 0 to 10 scale that asks patients to indicate the worst itching they have experienced over the past 24 h, with “0” labeled “no itching” and “10” labeled “worst itching imaginable”). 10 , 11 Randomization was performed on the first visit of the double‐blind phase using a computer‐generated randomization schedule. Patients, investigators, study staff, and the sponsor were blinded to study drug assignment during the double‐blind phase.

Study drug (difelikefalin or placebo) was administered as a single i.v. bolus into the venous line of the dialysis circuit at the end of each regular dialysis session. The study drug could be given either during or after rinse back of the dialysis circuit. Following the i.v. bolus of study drug, the venous line was flushed with at least 10 mL of normal saline.

The primary assessment scale was the COWS (Table 1), 12 completed by the study investigator during each of the dialysis visits in the 1‐week baseline period, each visit in the last week of the open‐label phase, and each visit during the double‐blind phase. Patients additionally completed 0–100‐point unipolar visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, feeling sick, feeling a bad effect, and hallucinating (under the same assessment schedule as the COWS), and completed the Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) 13 and the Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire (LSEQ) 14 at each visit during the last week of the open‐label phase (baseline) and at each visit of the double‐blind phase. Patients were trained on how to complete the VAS, SOWS, and LSEQ at the start of the study and received refresher training in the last week of the open‐label phase. The primary end point was the treatment difference between difelikefalin and placebo groups for the maximum COWS total score during the double‐blind phase, assessed in a noninferiority analysis. Secondary end points were the treatment differences between the difelikefalin and placebo groups for maximum SOWS total score during the double‐blind phase and for the mean COWS and SOWS total scores at each week of the double‐blind phase. Other withdrawal end points included the maximum scores during the double‐blind phase for the four aspects of LSEQ and the VAS scores, and the maximum values for post‐dialysis physiological measures (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, and body temperature). Blood sampling to assess the potential association of difelikefalin plasma concentrations with concurrent physical withdrawal symptoms was performed for all treated patients using methods previously described. 5 A validated method for the quantitation of difelikefalin in human plasma was used, based on solid phase extraction followed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry analysis with a range from 100 to 50,000 pg/mL. Safety assessments included assessments of treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs), pre‐dialysis vital signs, and pre‐dialysis clinical laboratory tests.

TABLE 1.

Assessments of physical withdrawal.

| Assessment | Assessor | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| COWS (Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale) | Clinician/investigator | Clinical observer‐reported assessment to evaluate symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Scale contains 11 items to rate signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal: pulse rate, gastrointestinal upset, sweating, tremor, restlessness, yawning, pupil size, anxiety or irritability, bone or joint aches, gooseflesh skin, runny nose or tearing. Each symptom is rated on a unique scale. Total scores for the scale range from 0 to 48, with scores <5 indicating no withdrawal, scores of 5–12 indicating mild withdrawal, scores of 13–24 indicating moderate withdrawal, scores of 25–36 indicating moderately severe withdrawal, and scores >36 indicating severe withdrawal | 12, 21 |

| SOWS (Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale) | Patient | Clinical questionnaire that subjects complete to evaluate symptoms of opioid withdrawal. The modified scale contained 15 items a that subjects rated in five categories on a scale of 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”): I feel anxious; I feel like yawning; I am perspiring; My eyes are teary; My nose is running; I have goosebumps; I am shaking; I have hot flushes; I have cold flushes; My bones and muscles ache; I feel restless; I feel nauseous; I feel like vomiting; My muscles twitch, I have stomach cramps. Total scores for the modified scale range from 0 to 60, with scores 1–10 indicating mild withdrawal, scores 11–20 indicating moderate withdrawal, and scores ≥21 indicating severe withdrawal | 13 |

| LSEQ (Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire) | Patient | Consists of 10 subject‐rated 10‐cm‐line analog questions that provide a measure of a person's subjectively perceived sleep quality and alertness on awakening. Lower scores on this scale indicate more problems with sleep. The questionnaire concerns four aspects of sleep and behavior: ease of getting to sleep (aspect range, 0–30 cm); perceived quality of sleep (0–20 cm); ease of awakening from sleep (0–20 cm); integrity of early morning behavior following wakening (0–30 cm) | 14 |

| Visual analog scales (VASs) for Pain, Feeling Sick, Bad Effect, and Hallucinating | Patient | Evaluated the degree to which subjects were experiencing potential drug effects. Answers were scored using a 0–100‐point unipolar VAS anchored on the left by “not at all” (score of 0) and on the right by “extremely” (score of 100). Higher scores on these scales indicate greater symptom severity. The following questions were asked: Are you in pain right now?; Are you feeling sick right now?; Are you feeling a bad effect right now?; Are you hallucinating right now? | 22 |

| Physiological measures | Clinician/investigator | Assessment of additional physiological measurements consisted of respiratory rate (breaths per min), oxygen saturation (%) measured by pulse oximetry, body temperature (°C), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), and heart rate (beats per min) | 8 |

Question 16 from the SOWS (“I feel like using now”) was removed, as it was not applicable to this study population.

Sample size

A sample size of 40 completed patients (n = 20 per treatment group) was originally estimated to yield a ≥80% coverage probability that a two‐sided 95% CI of the difference in maximum COWS scores between difelikefalin and placebo groups would fall within ±4 points on the COWS scale (using a common standard deviation [SD] of 4). Because only one side of this tolerance region was relevant for the primary noninferiority comparison, the upper 95% CI of the difference was compared with +4.

Due to site closures related to the COVID‐19 pandemic, only 30 subjects could be randomized in the double‐blind phase. Under the original sample size assumptions (i.e., assuming a common SD of 4), the power to show noninferiority from 30 patients dropped to 75%. A common SD of 3.75 would ensure 80% power, and therefore 30 subjects was still deemed adequate to meet the objectives of the study.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis was conducted in the per‐protocol population, defined as patients who received all double‐blind doses, did not have any missing COWS total scores during the double‐blind phase (after estimation of individual missing item responses), and did not have significant protocol deviations that would have affected the evaluation of the primary end point. The maximum COWS total scores in the double‐blind phase were analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. The model contained treatment (difelikefalin vs. placebo) and itching severity strata (none–mild or moderate–severe) as fixed effects and the baseline COWS score (i.e., before any study drug) as a covariate. Least squares (LS) means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for each treatment group and for the difference between them. Noninferiority was defined as the mean maximum COWS total score for the placebo group not being greater than +4 points higher (i.e., clinically worse) relative to the mean maximum COWS total score for the difelikefalin group. Thus, a one‐sided test was conducted at the 2.5% error level and the upper limit of the 95% CI of the between‐group difference was compared with +4. The noninferiority limit of +4 was chosen based on existing literature. 15 The Hodges–Lehmann estimate and 95% CI for the difference (placebo – difelikefalin) were calculated as a supportive analysis. Also, in a sensitivity analysis, the same ANCOVA model was applied to the full analysis population (i.e., patients who completed the open‐label phase and were randomized into the 2‐week double‐blind phase), assuming data were missing at random, with the maximum COWS total score for each subject calculated using observed data only.

Secondary analyses included the maximum SOWS total scores (analyzed with the same approach as for the COWS primary end point) and the total COWS and total SOWS scores for the two individual weeks of the double‐blind phase (analyzed using mixed effects models with repeated measures [MMRM]; see Supplemental Methods for further details). Additional end points, including the LSEQ, VAS scores, and physiological measures, were analyzed using the same ANCOVA and MMRM methods as for the COWS and SOWS data. Handling of missing data is described in the Supplemental Methods.

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize patient demographics, drug plasma concentrations, and safety data. TEAEs were coded using MedDRA version 22.0 and summarized by system organ class and preferred term. TEAEs potentially related to withdrawal during the double‐blind phase were identified based on preferred terms from published criteria. 8 , 16 These TEAEs were identified on a case‐by‐case basis during a blinded review prior to database lock.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

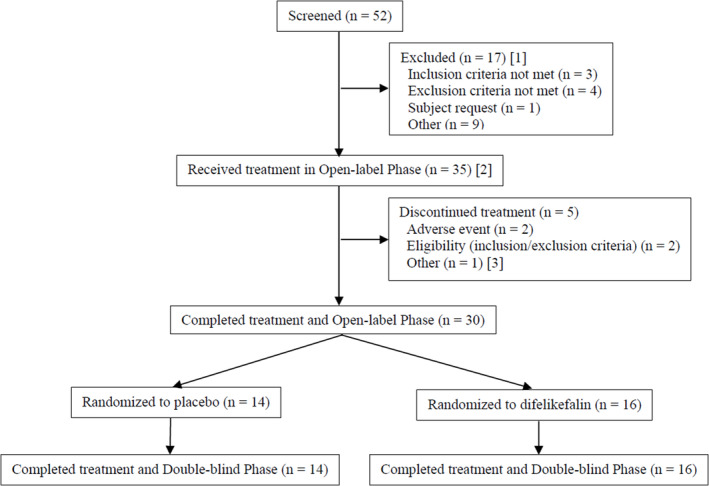

Fifty‐two patients were screened for participation in the study; of these, 17 failed screening, and 35 received difelikefalin during the open‐label phase (Figure 1). Closure of three study centers and reduced capacity at two other centers due to the COVID‐19 pandemic forced the study to close enrollment early.

FIGURE 1.

Patient disposition. [1] Does not include one patient who failed initial screening but was successfully enrolled with rescreening. [2] Includes one patient who failed initial screening but was successfully enrolled with rescreening. [3] Recipient of unscheduled kidney transplant.

Slightly more than half of the patients in the open‐label phase were male (57.1%), had a median (range) age of 58 (28–77) years, and were mostly Black or African American (91.4%) and not Hispanic or Latino (91.4%; Table 2). Thirty patients completed the open‐label phase and were randomized into the double‐blind phase (Figure 1); most of these patients (66.7%) were classified as having moderate‐to‐severe itching at the time of randomization. Demographic characteristics were similar between the open‐label phase and double‐blind phase populations. Five patients (14.3%) discontinued during the open‐label phase because of TEAEs (n = 2), becoming no longer eligible per inclusion/exclusion criteria (n = 2), and due to an unscheduled kidney transplant (n = 1). All 30 patients who were randomized completed treatment in the double‐blind phase (n = 16 difelikefalin; n = 14 placebo).

TABLE 2.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Open‐label phase | Double‐blind phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difelikefalin (N = 35) | Placebo (N = 14) | Difelikefalin (N = 16) | Overall (N = 30) | |

| Age (years), median [range] | 58 [28–77] | 56 [38–76] | 58 [28–77] | 58 [28–77] |

| Male gender, n (%) | 20 (57.1) | 7 (50.0) | 9 (56.3) | 16 (53.3) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Black or African American | 32 (91.4) | 14 (100.0) | 15 (93.8) | 29 (96.7) |

| White | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (3.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (5.7) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (6.7) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 32 (91.4) | 12 (85.7) | 15 (93.8) | 27 (90.0) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.9) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) |

| Baseline itch severity, n (%) a | ||||

| No itch–mild itch | N/A | 4 (28.6) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (33.3) |

| Moderate itch–severe itch | N/A | 10 (71.4) | 10 (62.5) | 20 (66.7) |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

For randomization into the double‐blind phase, patients were stratified according to whether they experienced moderate‐to‐severe itch at baseline, defined as at least one score >4 on the Worst Itching Intensity Numeric Rating Scale (WI‐NRS) (0–10 scale) during the 7‐day baseline period.

Pharmacokinetics

During the final week of the open‐label phase, mean difelikefalin pre‐dialysis plasma concentrations ranged from 380 to 671 pg/mL, and post‐dialysis plasma concentrations (obtained 5 min after dosing) ranged from 5369 to 7203 pg/mL (Figure S1).

At the first dialysis of the double‐blind phase, patients randomized to receive placebo had a mean difelikefalin pre‐dialysis concentration of 331 pg/mL (SD, 191 pg/mL). After one dialysis cycle, difelikefalin concentrations in 83% (10 of 12) of the patients randomized to placebo were below the level of quantification; after two dialysis cycles, difelikefalin was undetectable in all patients. The mean (SD) percentage of drug cleared by dialysis in the placebo group was 80.9% (8.7%). For patients randomized to remain on difelikefalin during the double‐blind phase, mean pre‐dialysis difelikefalin concentrations were maintained and comparable to the open‐label phase concentrations.

Across all patients, the mean (SD) percentage of difelikefalin cleared from plasma after the first dialysis post‐difelikefalin discontinuation was 78.6% (8.2%).

Physical dependence assessments

Physical dependence assessments were analyzed in the 28 patients included in the per protocol population (n = 15 difelikefalin, n = 13 placebo). During the baseline period, mean (SD) COWS total scores were 1.41 (0.99) for the difelikefalin group and 1.71 (1.21) for the placebo group, indicating no physical withdrawal signs or symptoms (i.e., scores <5).

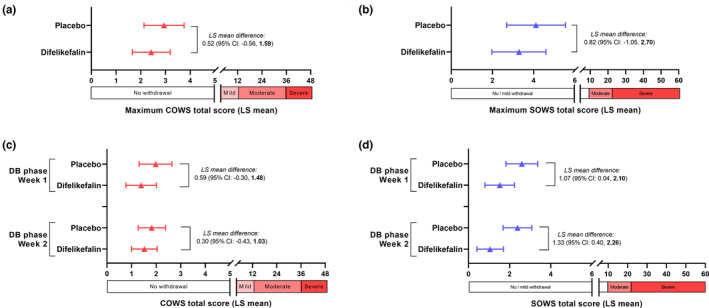

During the double‐blind phase, most patients in the per‐protocol population had a maximum observed COWS total score ≤4, indicating no withdrawal (13 patients [86.7%] in the difelikefalin group; 9 [69.2%] in the placebo group). For the remaining patients (2 patients [13.3%] in the difelikefalin group; 4 patients [30.8%] in the placebo group), the maximum observed COWS total scores were 5, which is within the mild withdrawal scale range. For the primary analysis, the LS mean maximum COWS total scores during the double‐blind phase were 2.42 for the difelikefalin group and 2.94 for the placebo group, with an LS mean difference of 0.52 (95% CI: −0.56, 1.59; Figure 2a). The upper limit of the 95% CI for the LS mean difference was 1.59, which was less than 4, indicating that withdrawal signs and symptoms in patients who abruptly discontinued difelikefalin were noninferior (i.e., not clinically worse) to those in patients who continued receiving difelikefalin. The results were similar when the analysis was repeated using the full analysis population (N = 30) assuming data were missing at random (LS mean difference, 0.49 [95% CI: −0.53, 1.51]). The analysis of COWS total score at Weeks 1 and 2 of the double‐blind phase also supported the conclusion of noninferiority (Figure 2c).

FIGURE 2.

Difference in average Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) scores. Upper panels show difference in least squares mean maximum COWS (a) and SOWS (b) total scores between difelikefalin and placebo groups (placebo − difelikefalin) during the double‐blind phase in the per‐protocol population (N = 28), analyzed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Lower panels show difference between the difelikefalin and placebo groups for COWS (c) and SOWS (d) total scores at Week 1 and Week 2 of the double‐blind phase by mixed effects model with repeated measures (MMRM) analysis. For the primary analysis (a), noninferiority was supported by the Hodges–Lehmann estimate of the median difference in maximum COWS total score (1.00 [95% CI: −1.00, 2.00]; predefined upper limit of the 95% CI to show noninferiority = +4). Error bars in plots represent 95% CI. CI, confidence interval; DB, double‐blind; LS, least squares.

Mean SOWS total scores in the week before randomization (i.e., baseline for SOWS analysis) were 3.18 (SD 3.61) for the difelikefalin group and 3.62 (SD 3.88) for the placebo group. During the double‐blind phase, the mean maximum SOWS total scores were 3.27 (3.35) for the difelikefalin group and 4.38 (3.23) for the placebo group. Most patients had a maximum observed SOWS total score ≤5 during the double‐blind phase (12 patients [75%] in the difelikefalin group; 9 [69%] in the placebo group) and the highest observed individual patient total score was 11 in the difelikefalin group and 10 in the placebo group (total SOWS scores of 1–10 indicate “mild withdrawal”).

The LS mean difference between the two groups in maximum SOWS scores was low in magnitude and the 95% CI included zero, indicating no difference (LS mean difference, 0.82 [95% CI: −1.05, 2.70]) (Figure 2b). The SOWS total scores at Weeks 1 and 2 of the double‐blind phase were higher for the placebo group than for the difelikefalin group (Figure 2d); however, mean scores for both groups were <3 and the magnitude of the differences (<1.5) was not clinically meaningful.

The difelikefalin and placebo groups showed no meaningful differences in LS mean minimum scores (i.e., 95% CIs containing zero) for any of the four aspects of sleep on the LSEQ during the double‐blind phase (Table S1). Similarly, there were no meaningful LS mean differences in maximum VAS scores for pain, feeling sick, feeling a bad effect, or hallucinating (Table S2).

Post‐dialysis physiological measurements during the double‐blind phase were generally no worse in patients switched to placebo than patients who continued difelikefalin (Table S3). Although LS mean maximum post‐dialysis diastolic blood pressure was higher in the placebo group (87.9 mmHg vs. 79.3 mmHg; LS mean difference, 8.58 mmHg [95% CI: 2.18, 14.99]), the mean post‐dialysis diastolic blood pressure was also higher in this group during the last week of the open‐label phase and there was no evidence of consistently increasing post‐dialysis diastolic or systolic blood pressure.

No increase in concomitant medications was recorded in either group during the double‐blind phase.

Safety

One patient (2.9%) experienced a TEAE that was considered related to difelikefalin (headache; mild in severity and which occurred during the open‐label phase; Table S4). Serious TEAEs were reported in four patients (11.4%); all occurred during the open‐label phase and none were considered related to study drug.

One TEAE potentially related to withdrawal (vomiting) was reported during the double‐blind phase in one patient (7.1%) randomized to placebo. The event occurred 7 days after the patient's final dose of open‐label study drug (Day 26 of the study), was considered mild and not related to study drug, and resolved the same day as onset. The patient did not report feeling like vomiting based on SOWS and no negative effects were reported on any VAS on Day 26. The subject had a prior medical history of vomiting. All other TEAEs reported during the double‐blind phase were either mild or moderate in severity, considered not related to study drug, and considered not potentially related to withdrawal.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the study results showed that HD patients treated for 3 weeks with difelikefalin (i.e., nine consecutive infusions) before an abrupt switch to placebo for 2 weeks did not demonstrate clinical signs or symptoms of withdrawal relative to patients who continued difelikefalin treatment. This is consistent with difelikefalin being a selective KOR agonist, with no activity at other receptors, like MOR, that are targets for opioid analgesics. 4 The mean maximum COWS total scores (primary end point) during the double‐blind phase were <5 (2.42 for the difelikefalin group; 2.94 for the placebo group), indicating no withdrawal in either group. Using a prespecified noninferiority margin of +4, the mean maximum score for patients switched to placebo was not clinically worse than that for patients who continued difelikefalin treatment, indicating that abruptly discontinuing chronic treatment with difelikefalin does not produce signs or symptoms of physical withdrawal. Additional assessments supported the COWS results, showing no differences between groups for the patient‐completed SOWS and no meaningful differences in sleep or physiological measurements.

The results from this study are consistent with those from the physical dependence assessments in a much larger subpopulation from the KALM‐1 phase III trial. 1 After completing a 12‐week double‐blind treatment period (placebo, N = 149; difelikefalin, N = 151), patients in KALM‐1 entered a 2‐week discontinuation period during which no study treatment was administered. No signs of withdrawal were observed during the discontinuation period, as determined by similar measures of physical dependence – the Short Opioid Withdrawal Scale 17 and the Objective Opioid Withdrawal Scale. 13 Discontinuations due to adverse events were also similar between patients previously treated with placebo or difelikefalin. Notably, in KALM‐1 and the present study, none of the adverse events reported were suggestive of withdrawal per DSM‐5 criteria 16 or as listed in FDA guidance. 8 Taken together, the results of these clinical studies informed the approved labeling for i.v. difelikefalin and indicate there is a low likelihood of withdrawal when discontinuing i.v. difelikefalin in clinical practice. Few studies have evaluated physical dependence of other KOR agonists. The potential for physical dependence of the centrally acting KOR agonist nalfurafine was investigated among HD patients participating in a 12‐month study. 18 Similar to the present study, modified SOWS scores did not differ between nalfurafine‐treated end‐stage renal disease patients with CKD‐aP and patients without CKD‐aP who served as non‐treatment controls. There was also no evidence of physical or psychological dependence in a post‐market surveillance study involving 3762 HD patients treated with nalfurafine for intractable pruritus. 19

Strengths of the present study were its double‐blind design and use of multiple subject‐ and clinician‐assessed withdrawal signs and symptoms measures. In addition, difelikefalin concentrations and their clearance upon discontinuation were confirmed in pharmacokinetic analyses. For the patients switched to placebo, residual plasma difelikefalin concentrations were cleared below the level of detection early into the double‐blind phase (after two dialysis cycles), which validates the 2‐week length of the double‐blind phase, especially since opioid withdrawal symptoms generally start occurring within the first days after discontinuation. 20 A limitation was that the study size was smaller than planned (N = 36 instead of N = 40) due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. However, even with this reduced sample size and a potentially wider 95% Cl with 36 patients, the primary end point was confirmed.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that abruptly discontinuing chronic treatment with difelikefalin in patients receiving HD does not produce signs or symptoms of physical withdrawal.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.H.S., C.M., and F.M. designed the research. All authors performed the research. All authors analyzed the data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by Cara Therapeutics. The authors employed by the sponsor were involved in the study's design, data interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

R.H.S., C.M., and F.M. are employed by and are shareholders in Cara Therapeutics, Inc. M.J.S. reports consultant fees from Cara Therapeutics, Inc.

Supporting information

Data S1

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Figure S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients who participated in this trial; the staff and the investigators at the participating dialysis centers; Dr. Sarbani Bhaduri (medical consultant) for assistance with the conduct of this trial; Dr. Patrick Noonan (PK Noonan Pharmaceutical Consulting, LLC) as clinical pharmacology consultant; and Drs. Joshua Cirulli and Warren Wen of Cara Therapeutics for assistance with the editorial process and critical review of the manuscript. We also thank the principal investigators involved in the study – Ahmed M. Awad, MD, Jeffrey J. Connaire, MD, Aaron M. Dommu, MD, Ari B. Geller, DO, and Joel M. Topf, MD – and thank Gary Smith (formerly at Syneos Health) for assistance with statistical analysis. Medical writing was provided by Jonathan M. Pitt, PhD (Evidera, Paris, France) and funded by Cara Therapeutics.

Spencer RH, Munera C, Shram MJ, Menzaghi F. Assessment of the physical dependence potential of difelikefalin: Randomized placebo‐controlled study in patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin Transl Sci. 2023;16:1559‐1568. doi: 10.1111/cts.13538

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fishbane S, Jamal A, Munera C, Wen W, Menzaghi F. A phase 3 trial of difelikefalin in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:222‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Topf J, Wooldridge T, McCafferty K, et al. Efficacy of difelikefalin for the treatment of moderate to severe pruritus in hemodialysis patients: pooled analysis of KALM‐1 and KALM‐2 phase 3 studies. Kidney Med. 2022;4:100512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . KORSUVA™ (difelikefalin) injection, for intravenous use. Initial U.S. Approval: 2021. Accessed May 18, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/214916s000lbl.pdf

- 4. Albert‐Vartanian A, Boyd MR, Hall AL, et al. Will peripherally restricted kappa‐opioid receptor agonists (pKORAs) relieve pain with less opioid adverse effects and abuse potential? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:371‐382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shram MJ, Spencer RH, Qian J, et al. Evaluation of the abuse potential of difelikefalin, a selective kappa‐opioid receptor agonist, in recreational polydrug users. Clin Transl Sci. 2022;15:535‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Viscusi ER, Torjman MC, Munera CL, Stauffer JW, Setnik BS, Bagal SN. Effect of difelikefalin, a selective kappa opioid receptor agonist, on respiratory depression: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14:1886‐1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration . The Controlled Substances Act. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.dea.gov/drug‐information/csa

- 8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for Industry. Assessment of Abuse Potential of Drugs; January, 2017. Accessed June 08, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/116739/download

- 9. Fishbane S, Mathur V, Germain MJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of difelikefalin for chronic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:600‐610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vernon M, Stander S, Munera C, Spencer RH, Menzaghi F. Clinically meaningful change in itch intensity scores: an evaluation in patients with chronic kidney disease‐associated pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1132‐1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vernon MK, Swett LL, Speck RM, et al. Psychometric validation and meaningful change thresholds of the Worst Itching Intensity Numerical Rating Scale for assessing itch in patients with chronic kidney disease‐associated pruritus. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD. Two new rating scales for opiate withdrawal. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13:293‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parrott AC, Hindmarch I. The Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire in psychopharmacological investigations – a review. Psychopharmacology. 1980;71:173‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nielsen S, Hillhouse M, Mooney L, Fahey J, Ling W. Comparing buprenorphine induction experience with heroin and prescription opioid users. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43:285‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gossop M. The development of a Short Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS). Addict Behav. 1990;15:487‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ueno Y, Mori A, Yanagita T. One year long‐term study on abuse liability of nalfurafine in hemodialysis patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51:823‐831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kozono H, Yoshitani H, Nakano R. Post‐marketing surveillance study of the safety and efficacy of nalfurafine hydrochloride (Remitch® capsules 2.5 μg) in 3,762 hemodialysis patients with intractable pruritus. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2018;11:9‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kosten TR, Baxter LE. Review article: effective management of opioid withdrawal symptoms: a gateway to opioid dependence treatment. Am J Addict. 2019;28:55‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tompkins DA, Bigelow GE, Harrison JA, Johnson RE, Fudala PJ, Strain EC. Concurrent validation of the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and single‐item indices against the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA) opioid withdrawal instrument. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:154‐159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. 1988;18:1007‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Figure S1

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.