Abstract

Background and Objective

To test the hypothesis that age-specific, sex-specific, and race-specific and ethnicity-specific incidence of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) increased in the United States over the last decade.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, validated International Classification of Diseases codes were used to identify all new cases of SAH (n = 39,475) in the State Inpatients Databases of New York and Florida (2007–2017). SAH counts were combined with Census data to calculate incidence. Joinpoint regression was used to compute the annual percentage change (APC) in incidence and to compare trends over time between demographic subgroups.

Results

Across the study period, the average annual age-standardized/sex-standardized incidence of SAH in cases per 100,000 population was 11.4, but incidence was significantly higher in women (13.1) compared with that in men (9.6), p < 0.001. Incidence also increased with age in both sexes (men aged 20–44 years: 3.6; men aged 65 years or older: 22.0). Age-standardized and sex-standardized incidence was greater in Black patients (15.4) compared with that in non-Hispanic White (NHW) patients (9.9) and other races and ethnicities, p < 0.001. On joinpoint regression, incidence increased over time (APC 0.7%, p < 0.001), but most of this increase occurred in men aged 45–64 years (APC 1.1%, p = 0.006), men aged 65 years or older (APC 2.3%, p < 0.001), and women aged 65 years or older (APC 0.7%, p = 0.009). Incidence in women aged 20–44 years declined (APC −0.7%, p = 0.017), while those in other age/sex groups remained unchanged over time. Incidence increased in Black patients (APC 1.8%, p = 0.014), whereas that in Asian, Hispanic, and NHW patients did not change significantly over time.

Discussion

Nontraumatic SAH incidence in the United States increased over the last decade predominantly in middle-aged men and elderly men and women. Incidence is disproportionately higher and increasing in Black patients, whereas that in other races and ethnicities did not change significantly over time.

Nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) accounts for 5%–10% of all strokes in the United States and is associated with significant mortality.1 Older studies estimate the annual incidence of SAH in the United States as between 6 and 11 cases per 100,000 population,2,3 with women having 1.2–1.7 times the incidence in men.4,5 Incidence also increases with age, but up to half of patients are typically younger than 55 years.2 The demographic characteristics of patients with stroke in the United States are changing. Increasingly more adults are being diagnosed with acute ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage at younger ages,6,7 but how SAH incidence has changed over time in various age and sex groups remains unknown.

Furthermore, Black patients are known to have higher SAH incidence compared with other races and ethnicities.8,9 It, however, remains uncertain how SAH incidence has changed in Black patients compared with that in other races and ethnicities over the last decade.

The aims of this study are to (1) define age-specific and sex-specific incidence of SAH in the United States and evaluate trends in incidence over the last decade and (2) quantify SAH incidence in various racial and ethnic groups and evaluate trends in incidence in Black patients compared with that in patients of other races and ethnicities.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We used administrative claims data from acute care hospitalizations contained in the State Inpatients Databases (SIDs) of Florida and New York from 2005 to 2017 to conduct a retrospective cohort study. These 2 states are large, demographically diverse states that combined account for >10% of the US population. The SIDs encompass the entire universe of inpatient discharges in participating states. The SIDs of these states also contain verified visitlink variables that allow tracking individual patients longitudinally across numerous hospitalizations over multiple years. Up to 10–34 discharge diagnoses for each patient encounter were coded using ICD-9-CM codes before October 2015 and ICD-10-CM codes afterward. To evaluate the generalizability of trends in the demographic characteristics of patients with SAH to the entire United States, we also obtained data on nontraumatic SAH from the 2007–2018 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), another Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP) database. The NIS is a 20% stratified sample of all US hospital discharges. Further details on the NIS and SID designs are available at hcup-us.ahrq.gov/.

US Population Data

Yearly estimates of the mid-year population of the selected states by age and sex for the period of the study were obtained from the US Census Bureau website (census.gov/). We obtained race and ethnicity data for Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black or African American, and non-Hispanic White (NHW) to allow consistency with HCUP racial and ethnic categories.

Study Population

We identified all adult hospitalizations ≥20 years with a primary or secondary diagnosis of nontraumatic SAH from the SID and NIS by querying these databases using ICD-9-CM code 430 and ICD-10-CM codes in the range of I60.xx. These codes have been previously validated and shown in the Center for Disease Control's Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Program to have a concordance of >90% with physician-reported SAH.10 To ensure that only nontraumatic cases were included, we excluded all hospitalizations with any discharge code corresponding to those for any form of traumatic intracranial injury (HCUP clinical classification system [HCUP CCS 233]). We further explored the external mechanisms of injury codes (E-codes) and excluded admissions with E-codes corresponding to those for falls (HCUP CCS code 2603), firearms (HCUP CCS 2605), machinery injury (HCUP CCS 2606), motor vehicle traffic injury (CCS 2607), pedal cyclist (CCS 2608), pedestrian injury (CCS 2609), and other transport injury (CCS 2610). We also excluded those with codes for injury from being “struck by or against” (CCS 2614). To ensure only spontaneous cases are captured, we excluded all hospitalizations with any diagnostic, procedural, or diagnosis-related group (DRG) codes corresponding to those for intravenous thrombolysis or those with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke and codes for mechanical thrombectomy. We excluded hospitalizations with codes for brain abscess or those with primary or metastatic brain/nervous system cancer (CCS 35) to restrict SAH admissions to those of likely vascular etiology. Hospitalizations in nonresidents of the participating states were also excluded.

Definition of Incident SAH

Incident SAH was defined as first hospitalization containing a diagnostic code for SAH with no previous hospitalization for SAH in that patient in the preceding years. We used a 2-year look back period (2005–2006) to minimize the influence of old SAH hospitalizations on study estimates.

Definition of Covariates

Patients undergoing endovascular coiling or microsurgical clipping were defined using a combination of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM and DRG codes, as described in eTable 1 (links.lww.com/WNL/C437). All other covariates were defined using ICD codes as also contained in eTable 1. We calculated the National Inpatient Sample Subarachnoid Severity Score (NISSSS), a validated SAH severity score that has been shown to correlate with SAH outcome for all patients as previously described.11,12 We also computed the validated Elixhauser comorbidity score for all patients.13 Data on the race/ethnicity of patients were defined using the HCUP variable “RACE.” Further details on HCUP race and ethnicity coding and information are available at hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/siddistnote.jsp?var=race#general.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of study participants were computed using descriptive statistics. We evaluated for possible linear trend in the prevalence of each baseline characteristic over time in both the SID and NIS by constructing a logistic regression model with each characteristic as the dependent variable and year of discharge as the independent variable, evaluated continuously, with significance of differences in trend over time assessed with the Wald test.

The overall annual incidence of SAH per 100,000 population was calculated from the number of SAH cases and the total adult population (aged 20 years or older) of the participating states for that year. Age-stratified and crude incidence estimates by race and ethnicity and sex were also obtained. Crude estimates were age standardized and/or sex standardized, as appropriate, to the 2010 US Census population to make data comparable between groups and across years.

We used joinpoint regression models with a permutation model selection method to compute the annualized percentage change (APC) in incidence and used pairwise comparison of the regression mean functions to compare the pace of change between demographic subgroups. All primary analyses were performed with Stata 16 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX). Joinpoint regression was performed with Joinpoint software, version 4.7.0.1 (Bethesda, MD). A 2-tailed value of α < 0.05 was used for statistical significance. Incidence estimates were not significantly different between states, so results were reported together for both states.

Missing Data

Racial and ethnic data were missing in 1.1% of study participants, and these were categorized into another/unknown category.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This project, conducted using the SIDs, was approved by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality after the agency reviewed and determined this project to be consistent with the HCUP Data Use Agreement.

Data Availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available for purchase from HCUP after completion of their data use agreement training.

Results

Trend in Sex and Age Distribution of Incident SAH Hospitalizations in New York and Florida

From 2007 to 2017, there were 39,475 new admissions for SAH in the states of New York and Florida. SAH was the primary discharge diagnosis in 70.6% of these admissions. Spontaneous intracerebral or intraventricular hemorrhage was the leading primary diagnosis when SAH was not the primary diagnosis (eTable 2, links.lww.com/WNL/C437).

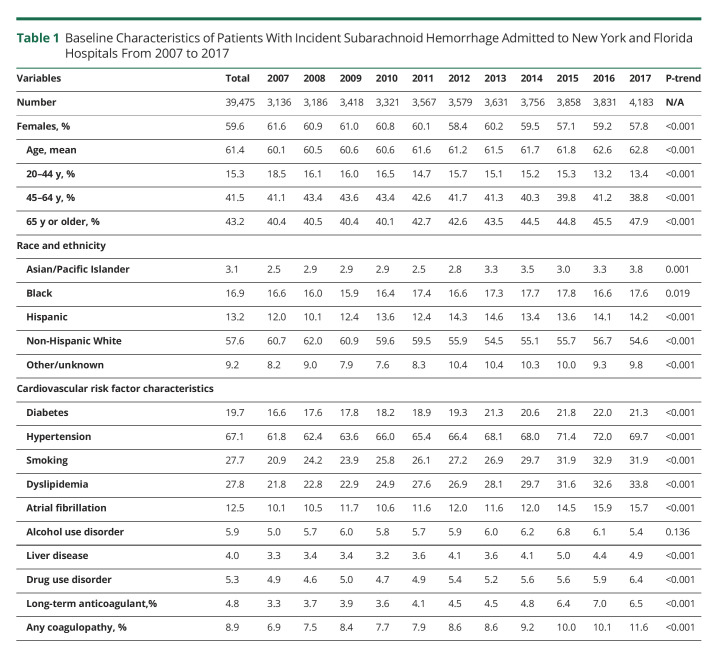

Almost 60% (59.6%) of these hospitalizations were in women, but the proportion of new admissions in women declined over time from 61.6% in 2007 to 57.8% in 2017 (p < 0.001), Table 1. The mean age was 61.4 years, but this increased over time from 60.1 years in 2007 to 62.8 years in 2017. Consistent with this increase, the proportion of admissions in elderly patients aged 65 years or older also increased over time, such that by 2017, almost half of all SAH admissions were in individuals aged 65 years or older (Table 1). More than half (57.6%) of SAH were in NHW patients, but this proportion declined over time just as the proportion in other racial groups increased significantly over time (all p values <0.05), Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Incident Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Admitted to New York and Florida Hospitals From 2007 to 2017

National Trends in Demographic Characteristics of SAH Hospitalizations in the 2007–2018 National Inpatient Sample

Similarly, over the period 2007–2018, the proportion of SAH admissions in the entire United States in women was 59.8%, but just as was the case in New York and Florida, this proportion declined over time from 61.4% in 2007 to 56.5% in 2018. The mean age of SAH admissions in the entire United States and the proportion in elderly patients aged 65 years or older also both increased over time such that by 2018, 47% of SAH nationally were in patients aged 65 years or older (eTable 3, links.lww.com/WNL/C437).

Other Baseline Characteristics

Approximately two-thirds (67.1%) of patients had comorbid codes for hypertension, and this proportion increased over time (p <0.001), Table 1. The prevalence of codes for atrial fibrillation increased by >60% over time from 10.1% in 2007 to 15.7% in 2017, while the prevalence of codes for long-term anticoagulant use or any coagulopathy each almost doubled across the study period (Table 1). The prevalence of drug use disorder also increased over time.

Population Incidence of SAH Over Time in Cases/100,000 Population

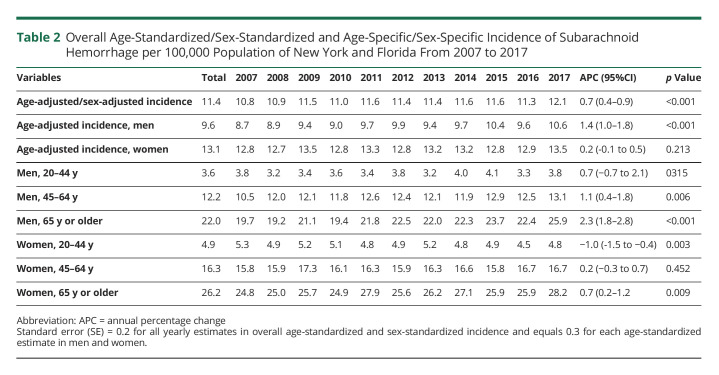

The average age-standardized and sex-standardized incidence of SAH across the study period was 11.4, but this differed by sex. The overall age-standardized incidence in women (13.1) was approximately 1.4 times the incidence in men (9.6), p value for comparison <0.001. Incidence increased with age, with both men and women aged 65 years or older having >5 times the incidence in young individuals aged 20–44 years in their corresponding sex group. However, in each age group, the incidence in women was significantly higher than the corresponding incidence in men (all p values for comparison <0.01). For example, among individuals aged 20–44 years, SAH incidence in women (4.9) was significantly higher compared with the incidence in men (3.6), p = 0.008 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall Age-Standardized/Sex-Standardized and Age-Specific/Sex-Specific Incidence of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage per 100,000 Population of New York and Florida From 2007 to 2017

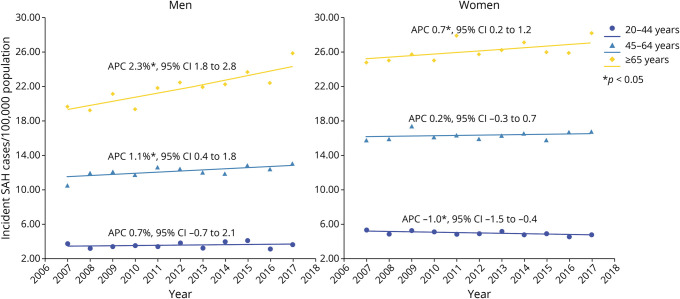

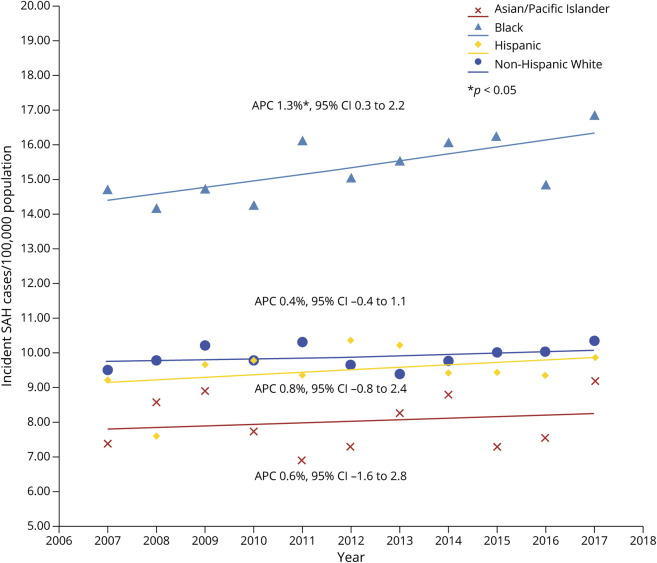

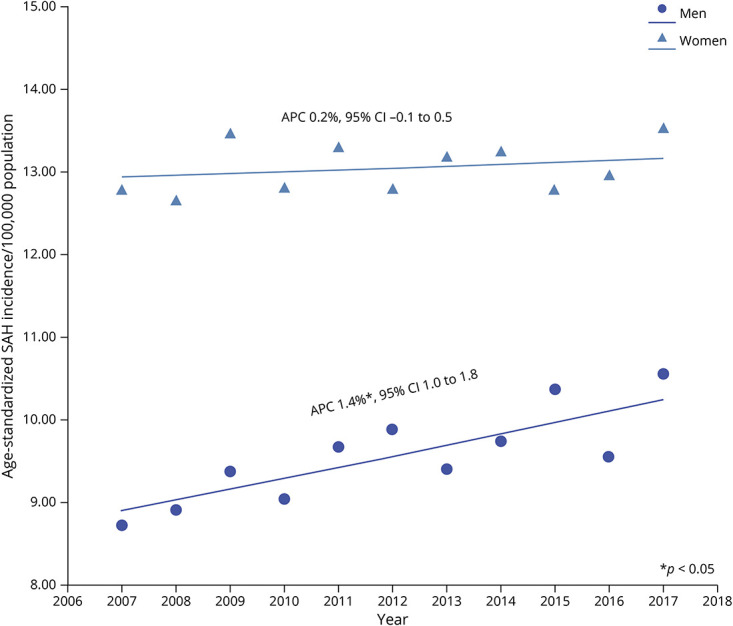

On joinpoint regression, age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of SAH increased averagely by 0.7% per year (Table 2), but most of the age-standardized increase occurred in men (APC 1.4%, p < 0.001). Age-standardized incidence in women remained unchanged over time. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trends in Age-Standardized Incidence of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in New York and Florida From 2007 to 2017 According to Sex.

*p < 0.05. Abbreviation: APC = annual percentage change.

Among women, incidence increased over time in elderly women aged 65 years or older (APC 0.7%, p = 0.009), but this was more than counterbalanced by declining incidence decline over time in women aged 20–44 years (APC % −1.0%; p = 0.003, Figure 2). Incidence in women aged 45–64 years did not change over time. By contrast, incidence increased both in middle-aged men aged 45–64 years and elderly men aged 65 years or older, while that in men aged 20–44 years remained constant over time (Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 2. Trends in Incidence of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in New York and Florida From 2007 to 2017 in Various Age/Sex Groups.

*p < 0.05. Abbreviation: APC = annual percentage change.

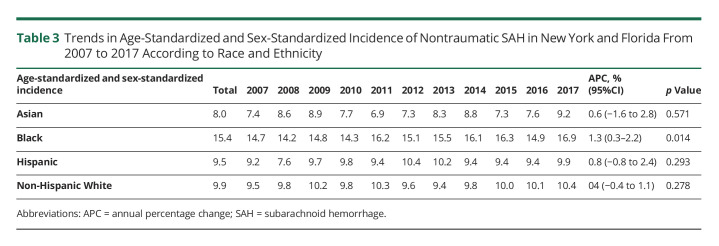

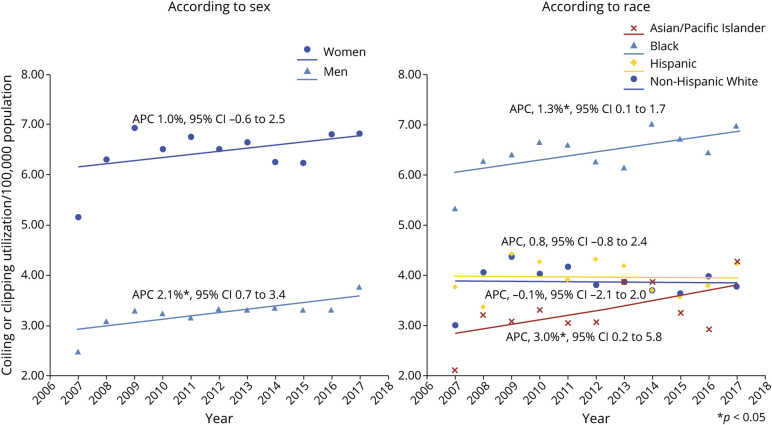

SAH Incidence per 100,000 Population According to Race and Ethnicity

Across the study period, the average age-standardized and sex-standardized incidence of SAH in Black patients (15.4) was more than 50% greater than the incidence in Asian patients (8.0), Hispanic patients (9.5), and NHW patients (9.9), p < 0.001 for each comparison; <0.001 (Table 3). On joinpoint regression, age-standardized and sex-standardized incidence increased over time in Black patients (p < 0.05), but did not change significantly over time in Asian, Hispanic, and NHW patients (Figure 3). Pairwise comparison of the regression mean function of Black patients vs NHW patients indicated that both slopes were not parallel (p < 0.001), indicating that the incidence gap between Black and NHW patients increased significantly over time. Black patients had greater prevalence of hypertension compared with NHW patients, but the prevalence of smoking and atrial fibrillation was significantly greater in NHW patients compared with that in Black patients (eTable 4, links.lww.com/WNL/C437). Black patients also had more severe SAH as measured by the NISSSS and a greater proportion with ≥3 comorbidities as measured by the Elixhauser score (eTable 4).

Table 3.

Trends in Age-Standardized and Sex-Standardized Incidence of Nontraumatic SAH in New York and Florida From 2007 to 2017 According to Race and Ethnicity

Figure 3. Trends in Age-Standardized and Sex-Standardized Incidence of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in New York and Florida From 2007 to 2017 according to Race and Ethnicity.

*p < 0.05. Abbreviation: APC = annual percentage change.

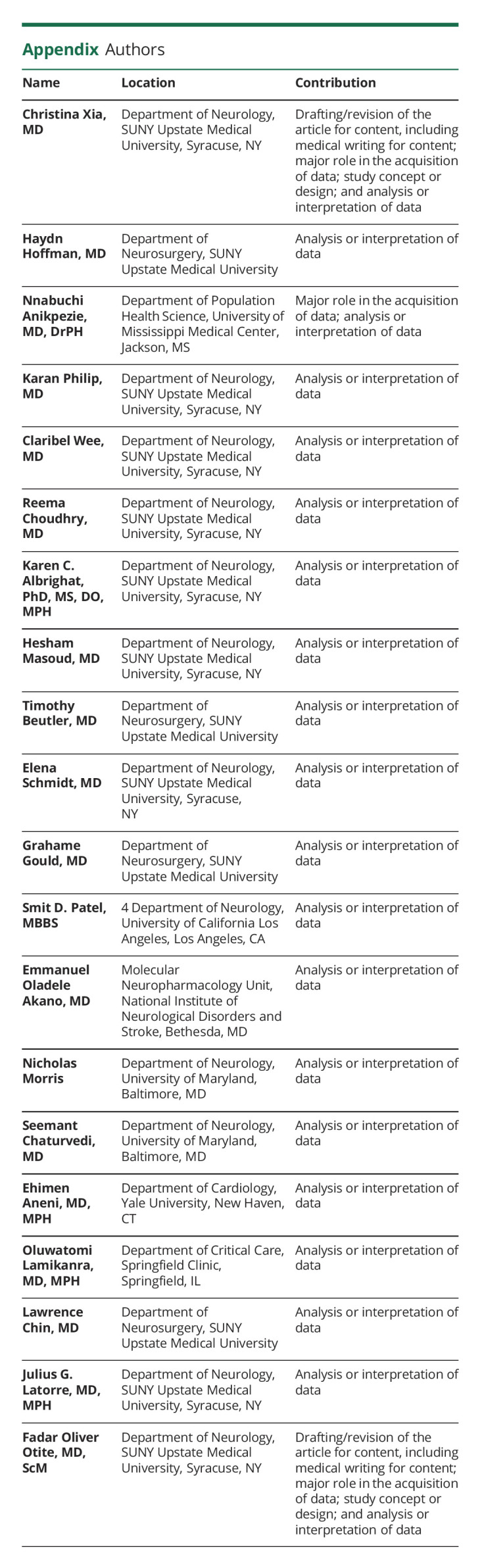

Trends in the Prevalence of Codes for Endovascular Coiling and/or Neurosurgical Clipping

From 2007 to 2017, 39.8% of incident hospitalizations for SAH in New York and Florida had codes corresponding to those for coiling or clipping. Projected to the entire population of these states, this corresponds to an average of 4.7 treatments for ruptured aneurysms per 100,000 population. On joinpoint regression, utilization of aneurysm treatment increased over time in men (APC 2.1%, 95% CI 0.7–3.4) but remained unchanged over time in women (Figure 4). Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted utilization of aneurysm treatment in Black patients was almost twice the frequency of utilization in other races and ethnicities (Figure 4). Whereas the frequency of utilization in NHW and Hispanic patients remained unchanged over time, usage in Black and Asian patients increased significantly over time. (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Trends in Age-Standardized and Sex-Standardized Utilization of Aneurysm Coiling or Clipping in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Hospitalizations in New York and Florida From 2007 to 2017.

*p < 0.05. Abbreviation: APC = annual percentage change.

Discussion

In this contemporary population-based study, we highlighted marked disparities in the incidence of SAH in New York and Florida by age, sex, and race and ethnicity. Incidence in women was greater than in men but increased over time in men, while that in women remained unchanged. Elderly patients aged 65 years or older and middle-aged men aged 45–64 years experienced increased incidence, but the incidence either declined or remained unchanged in other age groups. This change in SAH demographics differs from AIS and ICH, where most of the rising incidence is in young and middle-aged individuals.6 In the NIS analysis, we showed that this changing demographic profile may not be limited to these 2 states alone but likely occurred nationally.

The overall sex-specific incidence of 13.1 for women and 9.6 for men reported in this study are similar to the average sex-specific incidence of 12.5 and 10.7 in European women and men, respectively.2 However, the rising US SAH incidence differs from other countries, where incidence has remained stable or declined. Our results also contradict findings from Kentucky and Minnesota where incidences have not increased.14-17 In the Greater Cincinnati Northern Kentucky Stroke Study, SAH incidence varied from 5 to 11 cases/100,000 population for men and from 8 to 14 cases/100,000 population for women between 1994 and 2015, but there was no significant change in incidence. This study was limited by a small sample size of less than 500 cases with SAH.14 The Rochester Epidemiological Project reported a decline in aneurysmal SAH in the predominantly NHW population of Olmstead County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2016, but this study was also limited by very few cases with SAH (119 over 20 years). Varying case definitions could have accounted for the differing results because the aforementioned study was restricted to aneurysmal SAH alone. Racial differences in the underlying population studied may also be contributory because most of the increased incidence documented in our current study occurred in Black patients. Incidence in NHW patients remained unchanged over time.

Multiple factors could have contributed to the increase in SAH incidence. More frequent use of neuroimaging for headache18 and other acute neurologic complaints could have led to increased SAH detection. Historically, 12%–15% of patients with aneurysmal SAH die before hospital admission,19,20 but improvements in stroke education, public awareness, and emergency services could have facilitated earlier presentation. Increased incidence of stroke risk factors could have also contributed. We noted a >50% increase in the prevalence of atrial fibrillation and a 2-fold increase in long-term anticoagulation usage. The latter may have driven the increase in SAH incidence, especially among older patients and men who are more likely to have atrial fibrillation.21 Rising prevalence of drug use disorder could have led to increases in mycotic aneurysm–associated or sympathomimetic-induced SAH over time.22 Regardless of etiology, rising rates of SAH have implications for public health. Public education on stroke has focused on awareness of AIS symptoms, but increased education about SAH symptoms may also be indicated.

Smoking and hypertension are 2 of the strongest risk factors for SAH.23 In one recent meta-analysis,2 population-wide SAH incidence declined by 7.1% annually with each 1 mm of mercury drop in systolic blood pressure and by 2.4% for every percentage decline in smoking prevalence.2 In the United States, smoking prevalence in the general population is declining, but hypertension control remains a major challenge. Whereas the proportion of hypertensive individuals with controlled blood pressure in the United States increased in the period 1999–2000 to 2007–2008, this proportion did not change significantly from 2007–2008 to 2013–2014 and actually declined in the period from 2013–2014 to 2017–2018.24 In our study, we noted that the hypertension prevalence in patients with SAH increased over the study period. It is possible poor hypertension control in the general population is contributing to increased SAH risk despite decline in smoking prevalence. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate this and other potential factors.

Our finding of racial differences in SAH incidence are consistent with those of previous studies reporting a 1.6–2.1 times greater SAH incidence in Black patients compared with that in NHWpatients,9 but we extend the results of these studies by showing that incidence is increasing over time in Black patients while that of NHW patients remained unchanged over time. This is leading to a widening of the racial incidence gap over time Black patients tend to develop hypertension younger than NHW patients.25 Black patients are also more likely to have severe and uncontrolled hypertension compared with NHWpatients.24-26 Expanding hypertension control efforts in Black patients could reduce future SAH rates. However, the causes of higher SAH incidence in Black patients are not likely due to genetic differences, but most probably arise from socioeconomic factors including level of education, poverty level, lack of insurance, access to quality care, and possibly structural racism.27,28 In Australia, individuals residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas have 1.4 times higher aneurysmal SAH incidence than those in advantaged areas.29,30 Black race in the United States may partly be a marker for socioeconomic disadvantage. Tackling racial disparities in incidence will require multifaceted interventions targeted at stroke risk factors and socioeconomic inequity. Other studies have reported higher SAH incidence in Hispanic patients of Mexican and Caribbean descent compared with NHW patients,5,8 but we found no difference between Hispanic and NHW patients in this study. Hispanic patients represent a heterogeneous group with Mexican Hispanic patients possibly having different cardiovascular disease risk profiles compared with those of Caribbean, Latin American, or Cuban descent,31 and our results could have been confounded by different Hispanic populations.

Although ICD procedural and reimbursement codes may accurately identify the subset of patients with aneurysmal SAH undergoing coiling or clipping, the use of such codes alone may grossly underestimate true aneurysmal SAH incidence. As a result, we are unable to differentiate between aneurysmal and nonaneurysmal SAH. Only approximately 40% of patients with SAH had codes for coiling/clipping, but up to 75% of all SAH in the United States may be aneurysmal.3 More than 30% of patients with aneurysmal SAH in high-volume academic centers in the United States may be left untreated.32 This proportion is likely higher in smaller centers, in poor-grade SAH,33 and in the very elderly population. We showed that the utilization of coiling and clipping increased across the study period, but it is unclear whether this was due to increased incidence of aneurysmal SAH or changing clinical practices. Improvement in endovascular technology is allowing unruptured aneurysms to be electively treated more safely. Whether the increase in SAH cases in Black patients or the elderly population is due to fewer elective treatments of unruptured aneurysms remains unknown.

Our study is strengthened by its racially diverse sample, which allowed us to estimate national incidence of SAH in Asians/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, and NHW patients. Only 1.1% of study participants had missing data on race and ethnicity. Despite its strengths, our analysis underestimates true SAH incidence because it does not capture either mild cases not presenting for hospitalization or catastrophic cases that do not make it to the hospital. The internal validity of our analysis relies on the accuracy of the ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic and procedural codes, and coding inaccuracies cannot be excluded. Control of SAH risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and alcohol use disorder is not described in administrative databases, making it difficult to determine how this contributed to SAH incidence. We are unable to differentiate aneurysmal from nonaneurysmal SAH. We are also unable to differentiate between specific SAH etiologies such as reversible cerebral vasoconstriction, amyloid angiopathy, vasculitis, arteriovenous malformations, and others. The nature of administrative data also prevented us from determining family history of SAH. Race and ethnicity data in HCUP were likely not always obtained from self-report.34 Sex in this study was captured in a binary fashion and does not account for nonbinary gender expressions.

Nontraumatic SAH incidence in the United States increased predominantly in elderly individuals and in men over the last decade. Incidence is disproportionately higher in Black patients compared with that in patients of other races and ethnicities. Incidence increased in Black patients but remained unchanged over time in other races and ethnicities. Structural racism likely accounts for some of these observed racioethnic disparities, but further studies are needed to disentangle the causes.

Glossary

- APC

annual percentage change

- DRG

diagnosis-related group

- HCUP

Health Care Utilization Project

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases–9

- NHW

Non-Hispanic White

- NISSSS

National Inpatient Sample Subarachnoid Severity Score

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

- SID

State Inpatients Database

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Rincon F, Rossenwasser RH, Dumont A. The epidemiology of admissions of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in the United States. Neurosurgery. 2013;73(2):217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etminan N, Chang H-S, Hackenberg K, et al. Worldwide incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage according to region, time period, blood pressure, and smoking prevalence in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):588-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackey J, Khoury JC, Alwell K, et al. Stable incidence but declining case-fatality rates of subarachnoid hemorrhage in a population. Neurology. 2016;87(21):2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Rooij NK, Linn FHH, van der Plas JA, Algra A, Rinkel GJE. Incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review with emphasis on region, age, gender and time trends. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(12):1365-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eden SV, Meurer WJ, Sanchez BN, et al. Gender and ethnic differences in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2008;71(10):731-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bako AT, Pan A, Potter T, et al. Contemporary trends in the nationwide incidence of primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2022;53(3):e70–e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekker MS, Verhoeven JI, Vaartjes I, Van Nieuwenhuizen KM, Klijn CJ, de Leeuw F-E. Stroke incidence in young adults according to age, subtype, sex, and time trends. Neurology. 2019;92(21):e2444–e2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labovitz D, Halim A, Brent B, Boden-Albala B, Hauser W, Sacco R. Subarachnoid hemorrhage incidence among whites, blacks and caribbean hispanics: the northern manhattan study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26(3):147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broderick JP, Brott T, Tomsick T, Huster G, Miller R. The risk of subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhages in blacks as compared with whites. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(11):733-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang TE, Tong X, George MG, et al. Trends and factors associated with concordance between International classification of diseases, Ninth and Tenth revision, clinical modification codes and stroke clinical diagnoses. Stroke. 2019;50(8):1959-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawal S, Rinkel GJE, Fang J, et al. External validation and modification of nationwide inpatient sample subarachnoid hemorrhage severity score. Neurosurgery. 2021;89(4):591-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washington CW, Derdeyn CP, Dacey RG, Dhar R, Zipfel GJ. Analysis of subarachnoid hemorrhage using the nationwide inpatient sample: the NIS-SAH severity score and outcome measure. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(2):482-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care 2004;42(4):355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madsen TE, Khoury JC, Leppert M, et al. Temporal trends in stroke incidence over time by sex and age in the GCNKSS. Stroke. 2020;51(4):1070-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordan E, Graffeo CS, Rabinstein AA, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: long-term trends in incidence and survival in Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Neurosurg. 2021;134(3):878-883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Øie LR, Solheim O, Majewska P, et al. Incidence and case fatality of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage admitted to hospital between 2008 and 2014 in Norway. Acta neurochirurgica. 2020;162(9):2251-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H, Lai LT. Incidence and case-fatality of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in Australia. World Neurosurg. 2008-20182020;144:e438–e446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callaghan BC, Kerber KA, Pace RJ, Skolarus LE, Burke JF. Headaches and neuroimaging: high utilization and costs despite guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):819-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schievink WI, Wijdicks E, Parisi JE, Piepgras DG, Whisnant JP. Sudden death from aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 1995;45(5):871-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43(6):1711-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnussen C, Niiranen TJ, Ojeda FM, et al. Sex differences and similarities in atrial fibrillation epidemiology, risk factors, and mortality in community cohorts: results from the BiomarCaRE Consortium (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe). Circulation. 2017;136(17):1588-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salehi Omran S, Chatterjee A, Chen ML, Lerario MP, Merkler AE, Kamel H. National trends in hospitalizations for stroke associated with infective endocarditis and opioid use between 1993 and 2015. Stroke. 2019;50(3):577-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feigin VL, Rinkel GJ, Lawes CM, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: an updated systematic review of epidemiological studies. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2773-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, et al. Trends in blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension, 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. JAMA. 1999-20002017-20182020;324(12):1190-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine DA, Duncan PW, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Ogedegbe OG. Interventions targeting racial/ethnic disparities in stroke prevention and treatment. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3425-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard G, Prineas R, Moy C, et al. Racial and geographic differences in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension: the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Stroke. 2006;37(5):1171-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham G. Racial and ethnic differences in acute coronary syndrome and myocardial infarction within the United States: from demographics to outcomes. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(5):299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–e468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nichols L, Stirling C, Otahal P, Stankovich J, Gall S. Socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with a higher incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(3):660-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariajoseph FP, Huang H, Lai LT. Influence of socioeconomic status on the incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage and clinical recovery. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;95:70-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardener H, Sacco RL, Rundek T, Battistella V, Cheung YK, Elkind MS. Race and ethnic disparities in stroke incidence in the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke 2020;51(4):1064-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu F, Aiyagari V, Cross DT, Dacey RG, Diringer MN. Untreated subarachnoid hemorrhage: who, why, and when?. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2):244-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Oliveira Manoel AL, Mansur A, Silva GS, et al. Functional outcome after poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage: a single-center study and systematic literature review. Neurocrit Care. 2016;25(3):338-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nead KT, Hinkston CL, Wehner MR. Cautions when using race and ethnicity in administrative claims data sets. JAMA Health Forum. 2022:e221812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are publicly available for purchase from HCUP after completion of their data use agreement training.