Abstract

Background and Aims

This study aimed to histologically validate atrial structural remodelling associated with atrial fibrillation.

Methods and results

Patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation and endomyocardial atrial biopsy were included (n = 230; 67 ± 12 years old; 69 women). Electroanatomic mapping was performed during right atrial pacing. Voltage at the biopsy site (Vbiopsy), global left atrial voltage (VGLA), and the proportion of points with fractionated electrograms defined as ≥5 deflections in each electrogram (%Fractionated EGM) were evaluated. SCZtotal was calculated as the total width of slow conduction zones, defined as regions with a conduction velocity of <30 cm/s. Histological factors potentially associated with electroanatomic characteristics were evaluated using multiple linear regression analyses. Ultrastructural features and immune cell infiltration were evaluated by electron microscopy and immunohistochemical staining in 33 and 60 patients, respectively. Fibrosis, intercellular space, myofibrillar loss, and myocardial nuclear density were significantly associated with Vbiopsy (P = .014, P < .001, P < .001, and P = .002, respectively) and VGLA (P = .010, P < .001, P = .001, and P < .001, respectively). The intercellular space was associated with the %Fractionated EGM (P = .001). Fibrosis, intercellular space, and myofibrillar loss were associated with SCZtotal (P = .028, P < .001, and P = .015, respectively). Electron microscopy confirmed plasma components and immature collagen fibrils in the increased intercellular space and myofilament lysis in cardiomyocytes, depending on myofibrillar loss. Among the histological factors, the severity of myofibrillar loss was associated with an increase in macrophage infiltration.

Conclusion

Histological correlates of atrial structural remodelling were fibrosis, increased intercellular space, myofibrillar loss, and decreased nuclear density. Each histological component was defined using electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry studies.

Keywords: Atrial biopsy, Atrial fibrillation, Electroanatomic mapping, Fibrosis, Histology, Structural remodelling

Structured Graphical Abstract

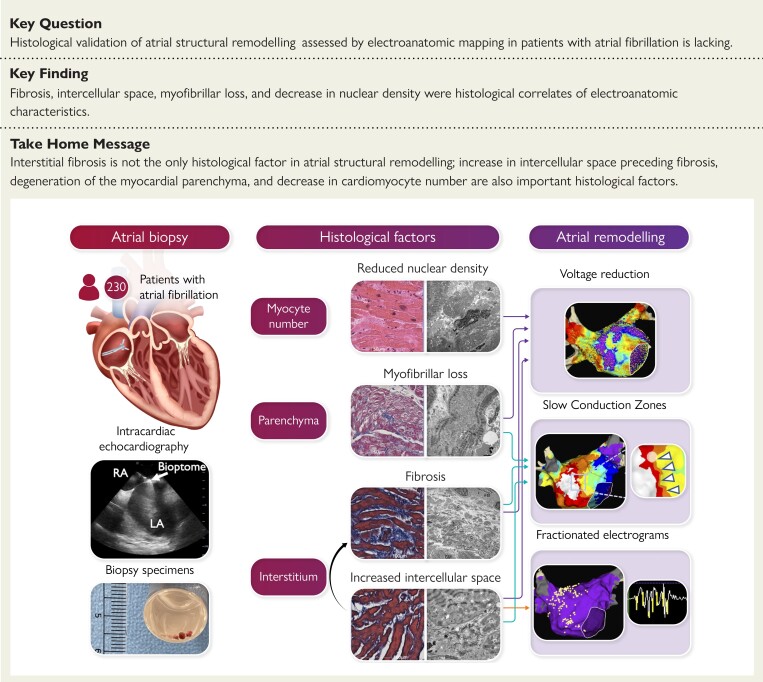

Structural Graphical Abstract.

Histological factors associated with atrial structural remodelling in patients with atrial fibrillation. LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Histopathology of atrial fibrillation: does this help us understand its pathogenesis?’, by R. Kawakami et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad515.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common arrhythmia, is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1,2 The AF is a progressive condition in which cardiomyocytes and interstitial changes cause contractile, electrical, and structural remodelling, which results in the initiation and perpetuation of AF.3,4 Fibrosis is a hallmark of structural remodelling, resulting in a substrate vulnerable to AF.5,6 Histologically, increased collagen deposition has been reported in patients with AF; however, these studies were limited to open-heart surgery or autopsy cases,7–10 or endomyocardial biopsy in small samples sizes.11,12

The low-voltage area (LVA) is considered a surrogate measure for localized fibrosis progression based on atrial bipolar voltage mapping studies and late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),13–18 indicating that atrial fibrosis progression is a heterogeneous process. However, from a histological perspective in post-mortem material, the extent of fibrosis did not differ among different locations in the atria, suggesting that fibrosis progression is a diffuse process.19 We recently reported that based on atrial biopsy and bipolar voltage, reduction in atrial bipolar voltage is a diffuse process with an inverse correlation between histological fibrosis extent and bipolar voltage.20 However, the study included a relatively small sample (n = 28) and only evaluated fibrosis extent in relation to bipolar voltage. This study aimed to histologically validate atrial structural remodelling, characterized by electroanatomic mapping, in a larger cohort.

Methods

Study design and population

This study was performed as part of the HEAL-AF and HEAL-AF2 (Histological Evaluation of Atrial Fibrillation Substrate Based on Atrial Septum Biopsy, Japanese UMIN Clinical Trial Registration UMIN000040781 and UMIN000044943) studies, which are ongoing observational studies evaluating 3-year outcomes after AF ablation based on histology of endomyocardial biopsy. A total of 349 Japanese patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation for non-valvular AF and high-density electroanatomic mapping during high right atrium (RA) pacing using a grid mapping catheter (GMC, AdvisorTM HD Grid, Abbott, St. Paul, MN, USA) between June 2020 and February 2022 were enrolled (AF group). None of the patients had undergone prior open-heart surgery. We excluded 107 patients from the analysis due to insufficient voltage mapping density with 5 mm interpolation (n = 14) or insufficient myocardial tissue sample, defined as a total myocardial area of <100 000 µm2 in the histological section (n = 93). Patients in whom the amyloid deposition was identified were excluded from the AF group and were separately analysed as an amyloid group (n = 12). The AF group comprised 230 patients. In addition, we analysed 26 patients without a history of documented AF as a control group who underwent catheter ablation for the left accessory pathway via the transseptal approach. High-density electroanatomic mapping of the atria was performed using the GMC, as in the AF group, although an atrial biopsy was not performed. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Saga University Hospital (approval reference numbers: 20200101 for HEAL-AF, 20200901 for HEAL-AF2, and 20200501 for the control group). All the patients provided written informed consent for participation in the study. This study conforms to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Details of the patient population and definitions of paroxysmal AF (PAF), persistent AF (PeAF), and long-standing persistent AF (LS-PeAF)21 were described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix. Eight autopsy cases were histologically analysed to compare the extent of fibrosis at the RA septum with that at various left atrium (LA) locations.

Electroanatomic mapping

Electroanatomic mapping was performed during high RA pacing at 100 b.p.m. using a 3D electroanatomical mapping system (EnSite PrecisionTM, Abbott) and GMC. Global LA voltage (VGLA) in the whole LA and regional LA voltage (VRLA) in the six anatomical regions were evaluated with the mean of the highest voltage at a sampling density of 1 cm2 (1 cm2 area method).20 The voltage at the biopsy site (Vbiopsy) was evaluated with the mean of the highest voltage at a sampling density of 0.25 cm2.20 Fractionated electrograms were evaluated using the fractionation mapping tool of EnSite PrecisionTM. Fractionated electrograms were defined as ≥5 deflections in each electrogram counted based on the following detection criteria: peak-to-peak voltage of >0.04 mV, width of 5 ms, and refractory of 6 ms. The proportion of points with fractionated electrograms was calculated as %Fractionated EGM. SCZtotal was calculated as the total width of slow conduction zones (SCZs), defined as regions with a conduction velocity of <30 cm/s.22 Further details are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix and Figures S1 and S2. The LVA was defined as an area with bipolar voltage of less than <0.5 mV.20 Details of the 1 cm2 area method, catheter ablation, induction of LA macroreentrant tachycardia (LAMRT), and follow-up are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix.

Atrial tissue sampling and processing for histology

Atrial biopsy samples were obtained from the posterior portion of the limbus of the fossa ovalis in the RA, under intracardiac echocardiography and fluoroscopy guidance. Three to five samples with a 1–3 mm sample size were successfully obtained from all patients. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was also performed on 33 patients.23 Details of atrial tissue sampling and processing for histology are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix and Figure S3.

Quantification of histological factors

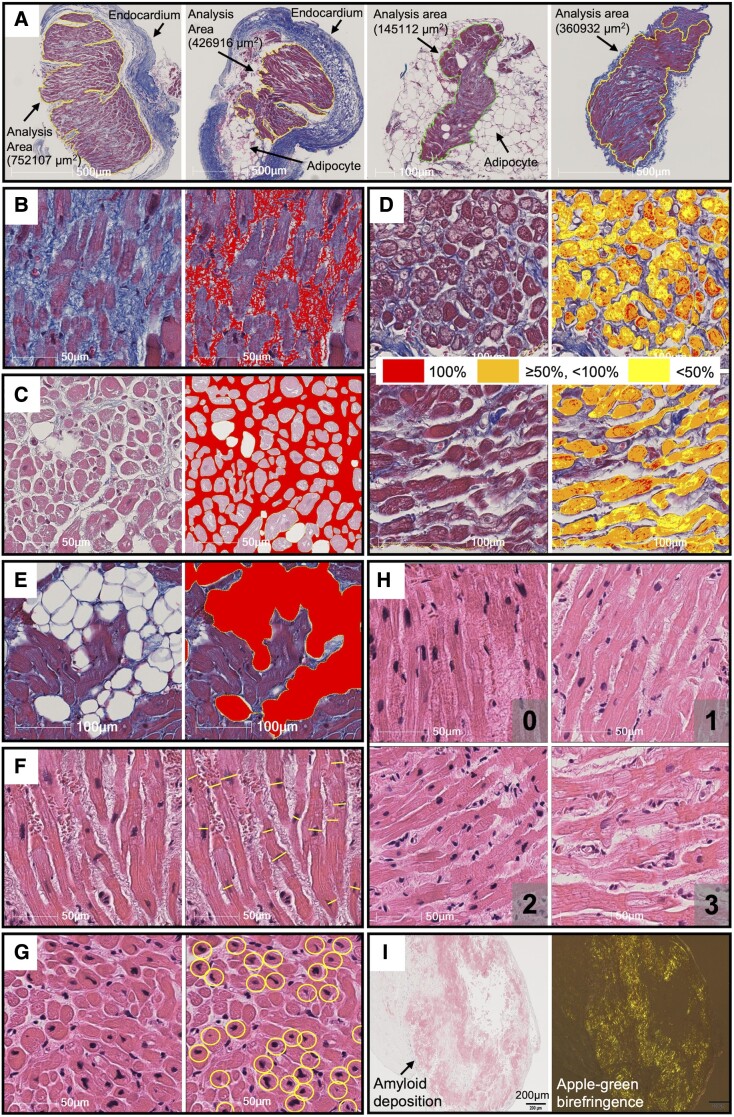

To determine the area for quantitative analysis, the edges of all myocardial tissues on the glass slides were manually annotated after excluding endocardium and large adipose tissue outside the myocardial tissue (Figure 1A). To determine the histological factors potentially associated with electroanatomic characteristics, the following parameters were quantitatively analysed: fibrosis extent (%Fibrosis), intercellular space extent (%Intercellular space), myofibrillar loss severity (%Myofibrillar loss), adipocyte extent (%Adipocytes), myocyte size, and myocardial nuclear density (Figure 1B–G). Myocyte disarray was semi-quantitatively analysed (Figure 1H). Amyloid deposition was identified by Congo red staining and apple-green birefringence under a polarizing microscope (Figure 1I). Details of the quantification of the histological factors are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix and Figure S4.

Figure 1.

Examples of measurement of histological factors. Analysis area was defined as the area surrounded by the solid lines excluding the endocardium and large adipose tissues (A). On Masson’s trichrome staining, fibrosis extent (B), intercellular space extent (C), myofibrillar loss severity (D), and adipocyte extent (E) were evaluated. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, myocyte size (F), and number of myocardial nuclei (G) were evaluated. Myocyte disarray was semi-quantitatively analysed and classified as minimal (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) (H). Amyloid deposition was identified by Congo red staining and birefringence under polarizing microscope (I). See Supplementary data online, Appendix for the details.

Tissue preparation and evaluation by electron microscopy

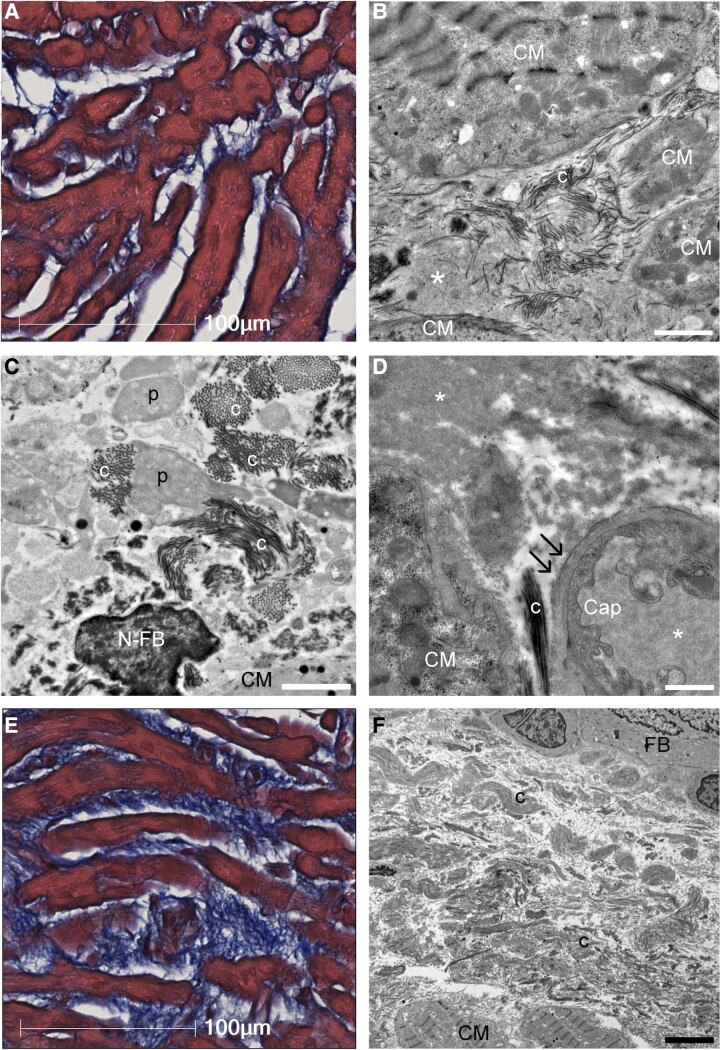

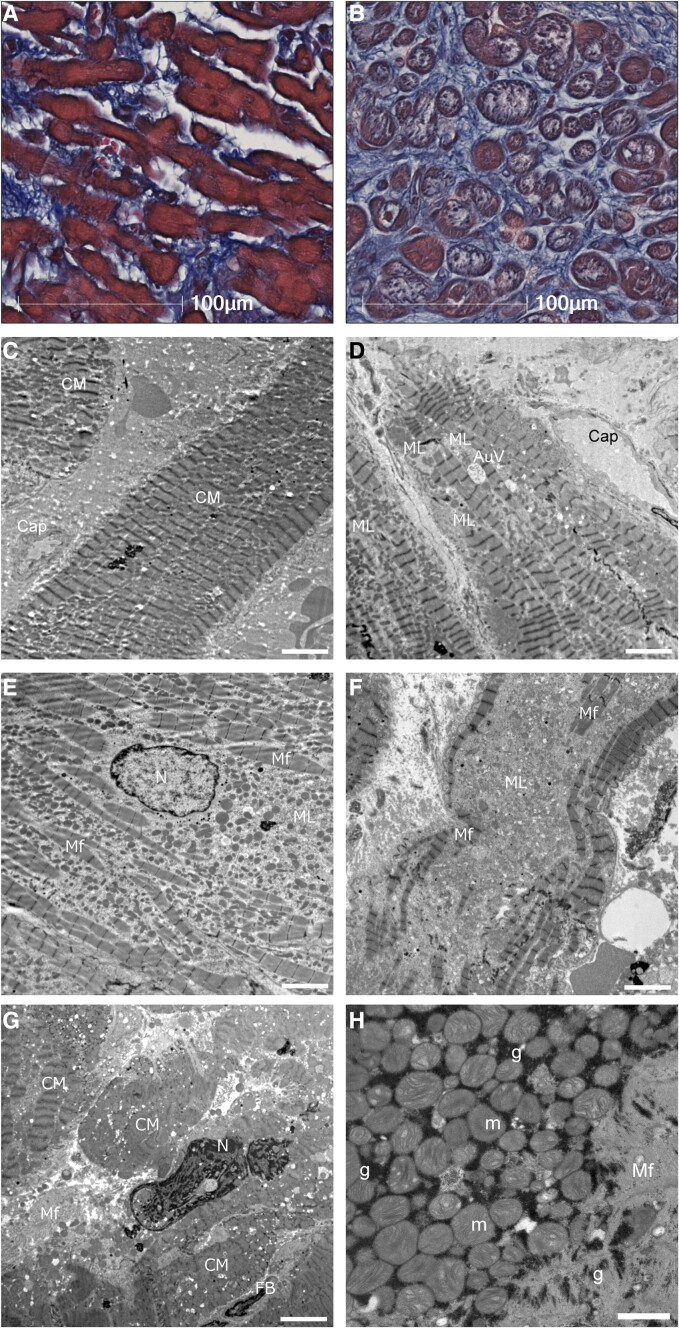

To compare the signal intensity of plasma components in the capillaries with areas without obvious structures within the increased intercellular spaces, the mean grey value within the selected area was measured (Figure 2). Myofilament changes were semi-quantitatively classified as no or minimal myofilament lysis (0), mild myofilament lysis (1), moderate myofilament lysis (2), or severe myofilament lysis (3) (Figure 3). Details of tissue preparation and evaluation by electron microscopy are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix and Figure S5.

Figure 2.

Ultrastructural characteristics of interstitial structures in atrial biopsy samples. (A) Light microscopy image of atrial tissue with mild fibrosis and increased interstitial space. Masson’s trichrome staining. (B) Transmission electron microscopy showed that the intercellular space, which was considered as structureless by light microscopy, was filled with plasma components (*) and interspersed with immature collagen fibrils (c). (C) Collagen fibrils extended toward the intercellular space from the surface of pseudopodia-like projections (p) of fibroblasts. (D) Laminarization of the capillary basement membrane (double arrow) was observed, indicating increased vascular permeability. The electron densities of intracapillary plasma components and interstitial plasma components were consistent (*). (E) Light microscopy image of atrial tissue with severe intercellular fibrosis. (F) Transmission electron microscopy image of (E). The intercellular area was filled with tight collagen fibrils. Scale bars = 2 μm in (B and C), 1 μm in (D), and 5 μm in (F). Cap, capillary; CM, cardiomyocyte; N-FB, nucleus of fibroblast; FB, fibroblast.

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural characteristics of cardiomyocytes in atrial biopsy samples. (A) In light microscopy, no or mild myofibrillar loss; (B) moderate to severe myofibrillar loss. (C) This case had no or minimum myofilament lysis in electron microscopy. (D) An example classified as mild myofilament lysis. An autophagic vacuole was near myofilament lysis area. (E) An example classified as moderate myofilament lysis. Area of myofilament lysis was spread out with preserved and scattered myofilaments. The shape of the nucleus (N) and chromatin are almost normal. (F) An example classified as severe myofilament lysis, disappeared myofilament. (G) A degenerated cardiomyocyte had swollen nuclei with chromatin aggregation. (H) Glycogen granules (g) were found between mitochondria (m) and myofilament. Scale bars = 5 μm in (C to G) and 1 μm in (H). CM, cardiomyocyte; Cap, capillary; ML, myofilament lysis; Mf, myofilaments; FB, fibroblast; AuV, autophagic vacuole.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect inflammatory cell infiltrates in 60 patients. The numbers of infiltrating CD3- (T lymphocytes), CD20- (B lymphocytes), CD45- (leucocyte common antigen), CD11c- (M1 macrophages), and CD163-positive cells (M2 macrophages) in the whole analysis area were counted and expressed as the number of cells/mm2. To analyse the relationship between each histological factor and inflammatory cell infiltration, the cell numbers were compared between the two groups (high vs. low), divided by the median value of each histological factor in the AF group. Details of the immunohistochemical staining are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix.

Histological analysis of autopsy cases

For the autopsy cases, tissue samples were obtained from the RA septum sites, including the limbus of the fossa ovalis, LA anterior, roof, inferior, posterior, and lateral regions to evaluate the extent of fibrosis. Details are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix and Figure S6.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed variables are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Continuous data were analysed using the unpaired t-test for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data were analysed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. To examine the associations between the two variables, Pearson’s (r) correlation coefficients were calculated for continuous data. All tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the JMP software (version 16.1.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R version 4.0.3. The details are shown in the Supplementary data online, Appendix.

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinical characteristics and electrophysiological data of the AF group (n = 230), amyloid group (n = 12), and the 107 patients who were excluded from the analysis are shown in Table 1. The patient characteristics across the quartiles of VGLA and those of the control groups are shown in the Supplementary data online, Table S1. The patient characteristics for whom electron microscopy or immunohistochemical staining was performed are shown in the Supplementary data online, Tables S2 and S3. Endomyocardial biopsies were performed before radiofrequency application in all patients. No biopsy-related complications occurred, except for transient local swelling at the biopsy site in two patients. Of 242 patients, 36 had a history of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) without additional ablation, except for cavotricuspid isthmus ablation. A comparison of the clinical characteristics of patients without a history of PVI and those with PVI is shown in the Supplementary data online, Table S4. Of the 206 patients without a history of PVI, 179 underwent voltage mapping before radiofrequency application, while 27 underwent voltage mapping after PVI alone because of frequent recurrences of AF after direct current cardioversion.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | AF group n = 230 |

Amyloid group n = 12 |

Excluded n = 107 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Age (range), years | 67 ± 12 (21–91) | 77 ± 7 (62–89) | 68 ± 11 (35–97) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 69 (30) | 4 (33) | 40 (37) |

| BSA, m2 | 1.72 ± 0.20 | 1.61 ± 0.19 | 1.69 ± 0.18 |

| Underlying heart disease, n (%) | 16 (7) | — | 10 (9) |

| Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 3 (1) | — | 1 (1) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 5 (2) | — | 5 (5) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 8 (3) | — | 4 (4) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (3–5) | 2 (1–3) |

| History of heart failure, n (%) | 56 (24) | 9 (75) | 29 (27) |

| HFrEF | 22 (10) | 0 (0) | 13 (12) |

| HFmrEF | 9 (4) | 2 (17) | 3 (3) |

| HFpEF | 25 (11) | 7 (58) | 13 (12) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 129 (56) | 8 (67) | 55 (51) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 42 (18) | 3 (25) | 18 (17) |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 19 (8) | 1 (8) | 14 (13) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 63 ± 18 | 51 ± 13 | 63 ± 16 |

| AF type, n (%) | |||

| PAF | 86 (37) | 5 (42) | 45 (42) |

| PeAF | 78 (34) | 6 (50) | 44 (41) |

| LS-PeAF | 66 (29) | 1 (8) | 18 (17) |

| Medication at baseline, n (%) | |||

| ACEi or ARB | 86 (37) | 7 (58) | 42 (39) |

| MRA | 15 (7) | 0 (0) | 5 (5) |

| Diuretics (other than MRA) | 30 (21) | 3 (25) | 17 (16) |

| Class I antiarrhythmic drugs | 34 (15) | 3 (25) | 20 (19) |

| Beta blockers | 119 (52) | 6 (50) | 53 (50) |

| Amiodarone | 19 (8) | 4 (33) | 11 (10) |

| Bepridil | 15 (7) | 1 (8) | 9 (8) |

| LA volume/BSA, mL/m2 | 96 ± 27 | 93 ± 12 | 99 ± 30 |

| LA diameter, mm | 41 ± 6 | 40 ± 5 | 42 ± 7 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 62 ± 12 | 59 ± 15 | 63 ± 13 |

| E/e’ | 9.4 ± 4.1 | 14.2 ± 6.4 | 9.9 ± 4.6 |

| Voltage parameters | |||

| Vbiopsy, mV | 8.5 ± 3.0 | 5.3 ± 3.1 | 7.7 ± 3.0 |

| VGLA, mV | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 5.3 ± 2.1 |

| LVA, n (%) | 31 (13) | 6 (50) | 16 (15) |

| Histological parameters | |||

| Tissue samples, n, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| Long diameter, mm, median (IQR) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

| Short diameter, mm, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| Myocardium (+)a, n, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | — | — |

| Amyloid (+), n, median (IQR) | — | 3 (2–4) | — |

| Analysis area, µm2 | 762 325 ± 583 116 | — | — |

| %Fibrosis, % | 7.0 ± 3.8 | — | — |

| %Intercellular space, % | 20.8 ± 8.4 | — | — |

| %Myofibrillar loss, % | 20.9 ± 10.4 | — | — |

| %Adipocyte, %, median (IQR) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | — | — |

| Myocyte size, µm | 16.8 ± 3.9 | — | — |

| Nuclear density, /mm2 | 384 ± 141 | — | — |

| Myocyte disarray, median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) | — | — |

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BSA, body surface area; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IQR, interquartile range; LA, left atrium; LS-PeAF, long-standing persistent AF; LV, left ventricle; LVA, presence of low-voltage area defined as <0.5 mV and ≥3.0 cm2; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; PAF, paroxysmal AF; PeAF, persistent AF; Vbiopsy, voltage at the biopsy site; VGLA, global left atrial voltage; %Adipocyte, extent of adipocyte; %Fibrosis, extent of fibrosis; %Intercellular space, extent of intercellular space; %Myofibrillar loss, severity of myofibrillar loss.

Number of tissue samples containing cardiomyocytes; LA volume was measured by computed tomography.

Evaluation of global left atrium voltage

Voltage maps of the LA were created using 1339 ± 377 acquired points. A total of 73 ± 17 areas of 1.0 cm2 were used to calculate VGLA using the 1 cm2-area method. Vbiopsy showed a positive correlation between VGLA and VRLA in all LA regions (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1). The accuracy of the 1 cm2-area method and other data indicating that the voltage reduction is a diffuse process are described in the Supplementary data online, Appendix and Figures S7–S9.

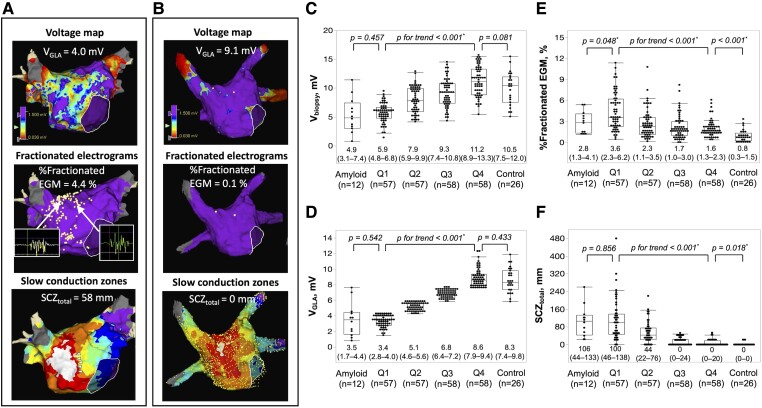

Relationship between global left atrium voltage and other electroanatomic characteristics

Fractionated electrograms and SCZs were frequently observed in the LA septum, anterior wall, and roof. The number of SCZs significantly increased as the VGLA quartile decreased [median, (IQR); Q1, 2 (1–3); Q2, 2 (1–2.5); Q3, 0 (0–1); Q4, 0 (0–0), P < 0.001]. Examples of an electroanatomic map in a patient with PeAF and a patient in the control group are shown in Figure 4A and B. The relationship between VGLA quartile and other electroanatomic characteristics including Vbiopsy, %Fractionated EGM, and SCZtotal is shown in Figure 4C–F. The electroanatomic characteristics progressed as the quartile decreased. These electroanatomic characteristics were also compared between the amyloid group and Q1 and between the control group and Q4 category. There was no significant difference in VGLA, Vbiopsy, and SCZtotal between the amyloid group and Q1, whereas %Fractionated EGM was significantly lower in the amyloid group. Both Vbiopsy and VGLA were similar in the control group compared with the Q4 category, whereas %Fractionated EGM and SCZtotal was significantly higher in the Q4 category.

Figure 4.

Examples of electroanatomic maps of a patient with persistent atrial fibrillation with reduced VGLA, high %fractionated EGM, and long SCZtotal (A) and a patient in the control group with preserved VGLA, very low %fractionated EGM, and no SCZ (B). White dots in the middle panels show the sites with fractionated electrograms. Examples of fractionated electrograms are shown. White arrow heads indicate local slow conduction zones at the anterior wall. The relationship between the quartile category of VGLA and Vbiopsy (C), VGLA (D), %Fractionated EGM (E), and SCZtotal (F). Comparisons between Q1 category vs. the amyloid group and Q4 category vs. the control group are also shown. * P < .05; LA, left atrium; SCZ, slow conduction zones; SCZtotal, total width of slow conduction zones; Vbiopsy, voltage at the biopsy site; VGLA, global LA voltage; %Fractionated EGM, proportion of fractionated electrograms.

Fractionated electrograms and slow conduction zones at the biopsy site

At the biopsy site, 56 ± 15 acquired points were evaluated for %Fractionated EGM, which tended to increase as the VGLA quartile decreased, although it was not statistically significant [median, (IQR); Q1, 1.7 (0–6.1); Q2, 0 (0–3.5); Q3, 0 (0–3.4); Q4, 0 (0–2.1); P = .059]. At the biopsy site, a slow conduction zone and LVA were identified in only two patients with the lowest VGLA and Vbiopsy shown in the Supplementary data online, Figure S10.

Histological findings

Histological findings are summarized in Table 1. Fibrosis appeared as interstitial fibrosis in all cases, with no evidence of replacement fibrosis. Hypertrophy of myocytes, defined as an average size >12 μm,24 was observed in 92% of patients. There was no evidence of myocarditis that met with ‘Dallas criteria’. Nuclear density was inversely correlated with age, myocyte size, and nuclear size (r = −0.364, P < .001; r = −0.572, P < .001; and r = −0.523, P < .001, respectively) (see Supplementary data online, Figure S11).

Ultrastructural findings in interstitium and cardiomyocytes

Immature collagen fibrils were frequently interspersed in the intercellular space (Figure 2A–C). In the increased intercellular space, the electron densities of the structureless area were similar to those of the plasma components in the capillaries (Figure 2D, see Supplementary data online, Figure S12). Laminarization of the capillary basement membrane was also frequently observed (Figure 2D). In atrial tissues with advanced fibrosis on light microscopy, the intercellular area was filled with tight collagen fibrils (Figure 2E and F).

In cardiomyocytes, various extents of myofilament lysis were semi-quantitatively classified by TEM (Figure 3). The extent of myofilament lysis was associated with the %Myofibrillar loss on light microscopy (see Supplementary data online, Figure S13). In specimens with myofilament lysis, the area of myofilament disappearance was mainly replaced by the mitochondria. Mitochondrial degeneration, autophagy (Figure 3D), nuclear chromatin aggregation (Figure 3G), and natriuretic peptide granules were observed. Glycogen granules were observed in all the samples examined (Figure 3H). The ultrastructural features are summarized in the Supplementary data online, Table S5.

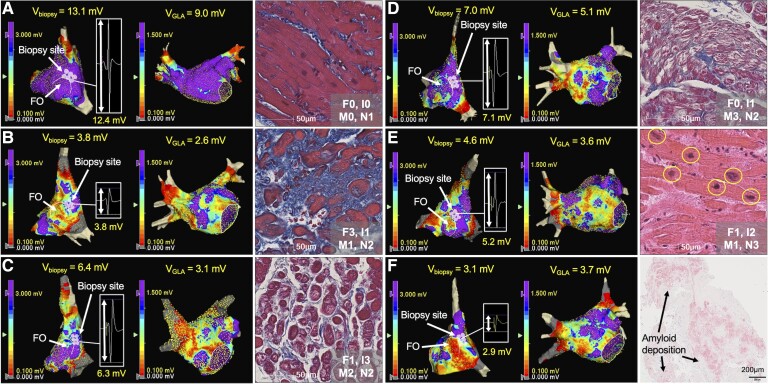

Histological factors associated with each electroanatomic characteristics

Table 2 presents the results. %Fibrosis, %Intercellular space, %Myofibrillar loss, and nuclear density were significantly associated with Vbiopsy (P = .014, P < .001, P < .001, and P = .002, respectively) and VGLA (P = .010, P < .001, P = .001, and P < .001, respectively). %Intercellular space was significantly associated with %Fractionated EGM (P = .001). %Fibrosis, %Intercellular space, and %Myofibrillar loss were also associated with SCZtotal (P = .028, P < .001, and P = .015, respectively). The linear mixed-effects model with all LA voltage data as a dependent variable also shows consistent results (see Supplementary data online, Table S6). Figure 5 shows the representative tissue images and voltage maps. Semi-quantification of histological factors is shown in the Supplementary data online, Figure S14. All patients had mild or more histological changes in at least one of the four histological factors. The scatter plots of each of the four histological factors and voltage characteristics are shown in the Supplementary data online, Figure S15. Subgroup analyses of histological factors associated with each electroanatomic characteristic for each sex, patients with PeAF/LS-PeAF, and patients without prior ablation are shown in the Supplementary data online, Tables S7–S9.

Table 2.

Histological factors associated with each electroanatomic characteristic

| Variables | Standardized coefficients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||

| V biopsy | V GLA | %Fractionated EGM | SCZtotal | V biopsy | VGLA | %Fractionated EGM | SCZtotal | |

| %Fibrosis, % | –0.453*** | –0.451*** | 0.280*** | 0.377*** | –0.180* | –0.190* | 0.102 | 0.185* |

| %Intercellular space, % | –0.305*** | –0.322*** | 0.279*** | 0.356*** | –0.295*** | –0.274*** | 0.254** | 0.293*** |

| %Myofibrillar loss, % | –0.361*** | –0.291*** | 0.145* | 0.179** | –0.307*** | –0.236** | 0.160 | 0.175* |

| %Adipocyte, % | 0.089 | 0.056 | –0.166* | –0.040 | 0.107 | 0.056 | –0.152 | –0.004 |

| Myocyte size, µm | –0.011 | –0.097 | 0.104 | 0.191** | 0.143 | 0.100 | –0.033 | 0.075 |

| Nuclear density, /mm2 | 0.291*** | 0.372*** | –0.235*** | –0.303*** | 0.235** | 0.297*** | –0.153 | –0.131 |

| Myocyte disarray, 0,1,2,3 | –0.062 | –0.061 | –0.001 | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.064 | –0.088 | –0.051 |

| Adjusted R2 | — | — | — | — | 0.334 | 0.322 | 0.154 | 0.233 |

*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; P value was adjusted using Benjamini–Hochberg method in multiple linear regression analysis; adjusted R2 (coefficient of determination) was calculated using all explanatory variables included in the multivariate model; SCZtotal, total width of slow conduction zones; Vbiopsy, voltage at the biopsy site; VGLA, global left atrial voltage; %Adipocyte, extent of adipocyte; %Fibrosis, extent of fibrosis; %Fractionated EGM, proportion of fractionated electrograms; %Intercellular space, extent of intercellular space; %Myofibrillar loss, severity of myofibrillar loss.

Figure 5.

Examples of voltage map of the right atrium septum and the whole left atrium, and histology. A patient without voltage reduction on Vbiopsy or VGLA showed no significant histological changes except mild reduction of nuclear density (A). Patients with reduction on Vbiopsy and VGLA mainly due to increased %Fibrosis (B), increased %Intercellular space (C), increased %Myofibrillar loss (D), decreased nuclear density (E), and amyloid deposition (F) are shown. F0–3, I0–3, M0–3, and N0–3 show semi-quantification of %Fibrosis, %Intercellular space, %Myofibrillar loss, and myocardial nuclear density as shown in the Supplementary data online, Figure S14. FO, fossa ovalis; Vbiopsy, voltage at the biopsy site; VGLA, global LA voltage; %Fibrosis, extent of fibrosis; %Intercellular space, extent of intercellular space; %Myofibrillar loss, severity of myofibrillar loss.

Clinical factors associated with each electroanatomic characteristic

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that age, female sex, body surface area (BSA), PeAF/LS-PeAF type, and the LA volume/BSA were significantly associated with VGLA. Only the LA volume/BSA was significantly associated with %Fractionated EGM. Age, female sex, and the LA volume/BSA were significantly associated with SCZtotal. Details are presented in the Supplementary data online, Table S10.

Histological factors associated with each electroanatomic characteristic with covariate adjustment

Histological factors associated with each electroanatomic characteristic were analysed using multiple linear regression analyses with covariate adjustments including age, BSA, female sex, LA volume/BSA, and PeAF/LS-PeAF type (see Supplementary data online, Table S11). %Fibrosis, %Intercellular space, and %Myofibrillar loss were significantly associated with both Vbiopsy and VGLA, however, nuclear density was not. %Intercellular space was significantly associated with %Fractionated EGM. %Fibrosis and %Intercellular space were significantly associated with SCZtotal.

Clinical factors associated with each histological factor

Multivariate analyses showed that PeAF/LS-PeAF type and LA volume/BSA were significantly associated with %Fibrosis. Only the PeAF/LS-PeAF type was significantly associated with %Intercellular space. None of the clinical factors were associated with %Myofibrillar loss. Age and the LA volume/BSA were significantly associated with nuclear density (see Supplementary data online, Table S12).

Histological factors associated with voltage reduction in Q1 category and Q2–4 category

In the Q2–Q4 category, all four histological factors were associated with VGLA, whereas in the Q1 category, only %Fibrosis was significantly associated with VGLA, indicating a close association between %Fibrosis and severe voltage reduction (see Supplementary data online, Table S13).

Inflammatory cell infiltration

The median (IQR) cell counts of CD3-, CD20-, CD45-, CD11c-, and CD163-positive cells were 7 (4–16), 0 (0–0), 25 (14–35), 5 (2–9), and 20 (8–33)/mm2, respectively. The median values of each histological factor to divide patients into two groups (high vs. low) was 6% for %Fibrosis, 20% for %Intercellular space, 18% for %Myofibrillar loss, and 363/mm2 for nuclear density. The cell counts of CD3- and CD45-positive cells did not differ between the high vs. low %Fibrosis, high vs. low %Intercellular space, high vs. low %Myofibrillar loss, and high vs. low nuclear density groups. CD11c- and CD163-positive cell counts were higher in the high %Myofibrillar loss group than in the low %Myofibrillar loss group, while there was no significant difference between high vs. low %Fibrosis, high vs. low %Intercellular space, and high vs. low nuclear density groups (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relationship between inflammatory cell infiltration and histological factors. The counts of CD45- (A), CD3- (B), CD11c- (C), and CD163-positive cells (D) per unit area (mm2) were compared between two groups: high vs. low %Fibrosis, high vs. low %Intercellular space, high vs. low %Myofibrillar loss, and high vs. low nuclear density groups. * P < .05; Arrows indicate positive cells in each immunohistochemical stain; F, %Fibrosis; I, %Intercellular space; M, %Myofibrillar loss; N, nuclear density.

Relationship between atrial fibrillation type and each electroanatomic characteristic or histological factor

Both VGLA and Vbiopsy were significantly lower in the LS-PeAF group than in the PAF group. %Fractionated EGM was more frequent, and SCZtotal was longer in LS-PeAF compared with PAF (see Supplementary data online, Figure S16). Histologically, %Fibrosis, %Intercellular space, and nuclear density were more advanced in LS-PeAF than in PAF, whereas %Myofibrillar loss did not differ between AF types (see Supplementary data online, Figure S17). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the number of infiltrating inflammatory cells did not differ between AF types (see Supplementary data online, Figure S18).

Inducibility of left atrial macroreentrant tachycardia

The LAMRT were induced in 18 patients (8%) in the AF group and four patients in the amyloid group (33%). The receiver operating characteristic analysis revealed that a decrease in VGLA showed strong accuracy in the inducibility of LAMRT (AUC, 0.958; cutoff, 4.2 mV; 95% CI, 0.917–0.979), while each histological factor showed weak discriminative power (AUC, 0.579–0.665) (see Supplementary data online, Figure S19).

Relationship between atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence and histological/electroanatomic characteristic

During a mean follow-up period of 18 ± 7 months, 32 patients in the AF group had atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence. Antiarrhythmic drugs were administered to 145 (63%) patients during the follow-up period. The cutoff value for each histological or electroanatomic characteristic to divide patients into two groups used the Youden index based on recurrence in patients with a follow-up of >12 months was 8.0 mV for Vbiopsy, 4.6 mV for VGLA, 1.3% for %Fractionated EGM, 32 mm for SCZtotal, 12.0% for %Fibrosis, 21.9% for %Intercellular space, 20.9% for %Myofibrillar loss, and 331/mm2 for nuclear density. Atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence was higher in patients in low Vbiopsy, low VGLA, high %Fractionated EGM, high SCZtotal, high %Fibrosis, and high %Intercellular space groups. However, there were no significant differences between the high vs. low %Myofibrillar loss, and high vs. low nuclear density groups (see Supplementary data online, Figure S20).

Histological findings of autopsy cases

The autopsy cases were 76 ± 7 years old, including two patients with AF. Patient characteristics, including cause of death, are shown in the Supplementary data online, Table S14. One patient died of fulminant myocarditis, but no obvious myocarditis was observed in the atria. There was no significant difference in %Fibrosis among the individual regions, including the RA septum and each LA region (P = .452; see Supplementary data online, Figure S6).

Discussion

Major findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively evaluate the relationship between electroanatomic characteristics and histological factors in AF patients. The major findings were as follows: (i) fibrosis, increased intercellular space, myofibrillar loss, and decreased myocardial nuclear density were significantly associated with voltage reduction; (ii) increased intercellular space was associated with increased %Fractionated EGM; (iii) fibrosis, increased intercellular space, and myofibrillar loss were associated with high SCZtotal (Structured Graphical Abstract ); (iv) fibrosis, increase in intercellular space, and decrease in nuclear density were more advanced in LS-PeAF compared with PAF, while myofibrillar loss did not differ between AF types; (v) fibrosis appeared as interstitial fibrosis with no evidence of replacement fibrosis; (vi) TEM identified plasma components, laminarization of the capillary basement membrane, immature collagen fibrils in the increased intercellular spaces, and myofilament lysis in cardiomyocytes, depending on the severity of myofibrillar loss; (vii) glycogen granules were preserved in all patients examined; (viii) macrophage infiltration was more significant in patients with higher myofibrillar loss; (ix) decrease in VGLA showed strong prognostic value for predicting the inducibility of LAMRT, while each histological factor showed weak prognostic value; (x) atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence was higher in patients with electroanatomically and histologically advanced atria, whereas there were no significant difference in high vs. low %Myofibrillar loss, and high vs. low nuclear density groups.

Histological factors associated with voltage reduction

The use of pathological changes assessed by atrial biopsy at a single location to represent those of the entire atrium assumes that structural atrial remodelling is a diffuse process. We have presented considerable data in a previous article20 and in the current study showing that atrial voltage reduction is a diffuse process. The present study identified not only fibrosis but also multiple histological factors associated with a reduction in bipolar voltage. As a result of these histological changes, there was a decrease in the amount of viable myocardium, which could be the main cause of voltage reduction. However, the relationship between these histological factors and the voltage is weak. The atrial voltage is also influenced by age, sex, LA volume, and wall thickness, which vary by region. The moderate correlation between Vbiopsy and VGLA or VRLA may be partly due to individual differences in the morphology and wall thickness of the limbus of the fossa ovalis and the LA.25,26 These considerations are consistent with the relationship between voltage and left ventricular wall thickness in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy reported by Glashan et al.27 They reported that both wall thickness and amount of viable myocardium influence unipolar and bipolar voltage of the left ventricle, and an increase in fibrosis reduces the amount of viable myocardium, resulting in a linear decrease in voltage. Female sex was associated with voltage, but not with any histological factors, suggesting that female sex is physiologically associated with lower myocardial mass. Previous MRI studies have reported that ventricular myocardial mass is significantly lower in women than in men.28

Consideration of a voltage cutoff to distinguish between healthy vs. diseased tissue

The process of pathological degeneration is continuous. In addition, atrial voltage is influenced by wall thickness, which varies by the atrial region. Therefore, it is not possible to establish a single cutoff value of voltage for a binary assessment of whether a region of interest is healthy. Areas with severe voltage reduction (e.g. <0.5 mV) suggest severe pathological degeneration; however, given that atrial remodelling is a diffuse process, other areas with higher voltage (e.g. >1.5 mV) in the same patient would also be highly degenerated.

Interstitial changes

Interstitial changes associated with electroanatomic characteristics include an increase in intercellular space and fibrosis. Electron microscopy revealed plasma components and immature collagen in the increased intercellular spaces. Only %Fibrosis was associated with voltage in the Q1 category, suggesting that fibrosis is the final pathway for atrial structural remodelling. These observations suggest that an increase in intercellular space precedes interstitial fibrosis. Only %Intercellular space was associated with %Fractionated EGM. An increase in intercellular space, as with the increase in collagen fibres, may cause electrical uncoupling of the side-to-side connections between myofibrils, producing a slow conduction or a zigzag course of transverse propagation and a consequent complexity of the waveforms, which facilitates reentry.29 This is consistent with the fact that patients with high %Intercellular space or high %Fibrosis had higher atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence rate. Furthermore, interstitial changes and signal complexity were more advanced in LS-PeAF. One possible reason why %Fibrosis, which is theoretically associated with fractionation, was not identified as an independent factor for %Fractionated EGM is that fractionated electrograms with severe low-voltage amplitude, which are associated with advanced fibrosis, could not be detected by the automated tool. Interestingly, relatively high %Fractionated EGM and %Intercellular space were observed even in patients in the Q4 category or PAF type, suggesting that interstitial change occurred in the early stage of structural remodelling in patients with AF. Furthermore, the extent of inflammatory cell infiltration did not differ between high vs. low %Intercellular space and high vs. low %Fibrosis, suggesting that these inflammatory cells may not be associated with severity of interstitial changes.

Parenchymal changes

The most significant feature of the parenchymal changes was myofibrillar loss. Transmission electron microscopy verified the myofilament lysis. The extent of myofibrillar loss was significantly associated with voltage but not with fractionated electrograms, AF type, or atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence. Therefore, this parenchymal change may not act as an AF substrate, although it may be an important feature of atrial cardiomyopathy. Macrophage infiltration was more significant in patients with higher %Myofibrillar loss. The estimated turnover of cardiomyocytes is extremely low in the adult heart.30 Cardiomyocytes partly maintain their homeostasis through ejection of difunctional mitochondria and other unwanted material in subcellular vesicles, which are efficiently taken up by macrophages via phagocytosis, preventing the extracellular accumulation of waste material.31 This mechanism can partly explain the greater infiltration of macrophages in atrial tissues with higher %Myofibrillar loss, where removal of the degenerated myofilament is necessary. The main cause of myofilament lysis remains unknown; however, genetic predisposition may increase susceptibility to myofilament lysis.32

Myocardial nuclear density

Nuclear density, a surrogate for cardiomyocyte number,33 was identified as a histological factor associated with voltage in this study. However, it was no longer significantly associated with voltage after adjusting for age. This can be explained by the close inverse relationship between age and nuclear density. Cardiomyocytes are thought not to proliferate principally, although recent studies have reported their proliferative capacity,30,34,35 and the myocardial cell number is expected to decrease with aging partly due to telomere shortening.36 An analysis of autopsy cases reported that cardiomyocyte number decreases with aging in the ventricles.37 The present study also revealed that myocardial cell size is inversely associated with nuclear density, suggesting that hypertrophic changes in atrial cardiomyocytes compensate for cardiomyocyte loss. Previous reports are consistent with this finding.37,38 Nuclear density was not associated with fractionated electrograms and atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence, suggesting that it does not act as an AF substrate but is another important factor in the development of atrial cardiomyopathy.

Histology and slow conduction zones

SCZtotal was associated with both parenchymal and interstitial changes, suggesting a close relationship between the reduction in myofibrils and local conduction abnormalities. Given the fact that SCZ is frequently identified in the anterior wall or roof despite the underlying diffuse remodelling process, it is likely that SCZ tends to appear at sites with changes in myofiber architecture or wall thickness.39

Inducibility of left atrium macroreentrant tachycardia

We previously reported that inducibility of LAMRT was associated with the presence of LVA defined as <0.5 mV, which reflects a reduction in VGLA, and the majority of the critical isthmus were located in the LVA.20 This study confirmed that LAMRT was strongly associated with a reduction in VGLA, suggesting that a severe reduction in global voltage results in the appearance of local SCZs, which act as substrates for LAMRT. We speculate that previous reports of ablation strategies targeting LVA, including the recent multicentre randomized ERASE-AF trial, may have prophylactically ablated the substrate of LAMRT, which resulted in better atrial tachyarrhythmia-free survival.13,16,40

Histological characteristics in atrial fibrillation patients with early stage of progression

The present study showed that patients with AF in the early stage of progression, suggested by PAF type or preserved voltage, had considerable histological changes. An increase in intercellular space could be the initial interstitial change. No clinical factors, except PeAF/LS-PeAF type, were associated with %Intercellular space. The cause of the increase in intercellular space in patients during the early stages of progression is unknown. The TEM revealed that glycogen granules were preserved, ruling out ischaemia as the cause of tissue degeneration. Laminarization of the capillary basement membrane indicates increased vascular permeability.41 Genetic factors associated with adhesion molecules may play a role in the pathogenesis.42 Animal studies have reported that AF persistence itself increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF-induced extravascular leakage increases intercellular space.43 The AF persistence also reportedly causes gap junction distribution abnormalities,44 which may contribute to increased intercellular space due to reduced mechanical adhesion between myocytes. The AF is a progressive disease,45 and intervention early in the natural history of AF, as reported by the EARLY-AF trial,46 may prevent progression of structural remodelling by reducing the AF burden and interrupting AF-induced interstitial remodelling.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, as no biopsy was performed in the control group, it is unclear whether the results can be applied to patients without AF. Second, the study excluded cases that did not have a sufficient tissue sample (defined as ≥100 000 µm2); however, this definition is tentative, and sampling errors could have occurred in inferring the tissue properties of the entire atria. Third, fibrosis was excluded from the measurement of %Intercellular space, and the %Intercellular space decreased with fibrotic progression. This may have affected our statistical findings. Fourth, although the effects of contraction bands, crush artifacts, and uneven staining were excluded to the extent possible to enable the evaluation of myofibrillar loss, these effects cannot be completely excluded. Additionally, the evaluation of myofibrillar loss was relative, with the area of the highest staining density used as the reference density. It is possible that the area with the highest staining density was already affected by myofibrillar loss. Fifth, we analysed the voltage during high RA pacing, but not during AF or pacing from different sites, which affects the voltage amplitudes. Sixth, the sample size of autopsy cases was small, and only two patients had a history of AF. Hence, the overall fibrosis rate was relatively low, and it cannot be concluded that there was no difference in the extent of fibrosis in various regions. Seventh, even though voltage reduction is a diffuse process, we did not obtain tissue samples directly from the LVAs, SCZs, or regions with fractionated electrograms. Therefore, regional remodelling superimposed on global remodelling cannot be ruled out.

Conclusions

Histological correlates of atrial structural remodelling were fibrosis, increased intercellular space, myofibrillar loss, and decreased nuclear density. Each histological component was defined using electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry studies. Further analysis of the process of atrial remodelling will help to elucidate the pathogenesis of atrial cardiomyopathy underlying AF and identify new therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Kaori Yamaguchi, Yuriko Susuki, Junko Marugami, and Yumiko Tsugitomi for data analysis and sample processing; Yumi Ishii and Masaki Takahashi for electron microscopy analysis; and the Amyloidosis Center, Kumamoto University Hospital, for the histological assessment of amyloid deposition. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Contributor Information

Yuya Takahashi, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Takanori Yamaguchi, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Toyokazu Otsubo, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Kana Nakashima, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Kodai Shinzato, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Ryosuke Osako, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Shigeki Shichida, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Yuki Kawano, Division of Cardiology, Saiseikai Futsukaichi Hospital, 3-13-1, Yumachi, Chikushino, Fukoka 818-8516, Japan.

Akira Fukui, Department of Cardiology and Clinical Examination, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, 1-1, Idaigaoka, Hasama, Yufu, Oita 879-5593, Japan.

Atsushi Kawaguchi, Education and Research Center for Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Shinichi Aishima, Department of Pathology and Microbiology, Saga University, Saga, Japan.

Tsunenori Saito, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Nippon Medical School Tama Nagayama Hospital, Tama, Tokyo, Japan.

Naohiko Takahashi, Department of Cardiology and Clinical Examination, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, 1-1, Idaigaoka, Hasama, Yufu, Oita 879-5593, Japan.

Koichi Node, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saga University, 5-1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal online.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

Takanori Yamaguchi received honoraria from Abbott Medical Japan and Medtronic Japan. Takanori Yamaguchi, Yuya Takahashi, and Toyokazu Otsubo are also affiliated with the Department of Advanced Management of Cardiac Arrhythmia, Saga University, sponsored by Abbott Medical Japan, Nihon Kohden Corporation, Medtronic Japan, Japan Lifeline, Boston Scientific Japan, and Fides-ONE Corporation. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (JP21K08056) and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP22ek0210164 to T.Y.).

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Saga University Hospital.

Pre-registered Clinical Trial Number

The pre-registered clinical trial number is Japanese UMIN Clinical Trial Registration UMIN000040781 and UMIN000044943.

References

- 1. Wolf PA, Mitchell JB, Baker CS, Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB. Impact of atrial fibrillation on mortality, stroke, and medical costs. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:229–234. 10.1001/archinte.158.3.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pappone C, Rosanio S, Augello G, Gallus G, Vicedomini G, Mazzone P, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and quality of life after circumferential pulmonary vein ablation for atrial fibrillation: outcomes from a controlled nonrandomized long-term study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:185–197. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00577-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allessie M, Ausma J, Schotten U. Electrical, contractile and structural remodeling during atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 2002;54:230–246. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00258-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wijffels MCEF, Kirchhof CJHJ, Dorland R, Allessie MA. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation 1995;92:1954–1968. 10.1161/01.CIR.92.7.1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weber KT, Sun Y, Tyagi SC, Cleutjens JPM. Collagen network of the myocardium: function, structural remodeling and regulatory mechanisms. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1994;26:279–292. 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Everett TH, Olgin JE. Atrial fibrosis and the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2007;4:S24–S27. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boldt A, Wetzel U, Lauschke J, Weigl J, Gummert J, Hindricks G, et al. Fibrosis in left atrial tissue of patients with atrial fibrillation with and without underlying mitral valve disease. Heart 2004;90:400–405. 10.1136/hrt.2003.015347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corradi D, Callegari S, Benussi S, Maestri R, Pastori P, Nascimbene S, et al. Myocyte changes and their left atrial distribution in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation related to mitral valve disease. Hum Pathol 2005;36:1080–1089. 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu J, Cui G, Esmailian F, Plunkett M, Marelli D, Ardehali A, et al. Atrial extracellular matrix remodeling and the maintenance of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2004;109:363–368. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109495.02213.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitrofanova LB, Orshanskaya V, Ho SY, Platonov PG. Histological evidence of inflammatory reaction associated with fibrosis in the atrial and ventricular walls in a case-control study of patients with history of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2016;18:iv156–iv162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frustaci A, Chimenti C, Bellocci F, Morgante E, Russo MA, Maseri A. Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation 1997;96:1180–1184. 10.1161/01.CIR.96.4.1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sepehri Shamloo A, Husser D, Buettner P, Klingel K, Hindricks G, Bollmann A. Atrial septum biopsy for direct substrate characterization in atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:308–312. 10.1111/jce.14308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kottkamp H, Berg J, Bender R, Rieger A, Schreiber D. Box isolation of fibrotic areas (BIFA): a patient-tailored substrate modification approach for ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2016;27:22–30. 10.1111/jce.12870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verma A, Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, Martin NO, Kilicaslan F, Minor S, et al. Pre-existent left atrial scarring in patients undergoing pulmonary vein antrum isolation: an independent predictor of procedure failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:285–292. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yamaguchi T, Tsuchiya T, Nagamoto Y, Miyamoto K, Murotani K, Okishige K, et al. Long-term results of pulmonary vein antrum isolation in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis in regards to substrates and pulmonary vein reconnections. Europace 2014;16:511–520. 10.1093/europace/eut265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamaguchi T, Tsuchiya T, Nakahara S, Fukui A, Nagamoto Y, Murotani K, et al. Efficacy of left atrial voltage-based catheter ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2016;27:1055–1063. 10.1111/jce.13019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Masuda M, Fujita M, Iida O, Okamoto S, Ishihara T, Nanto K, et al. Left atrial low-voltage areas predict atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2018;257:97–101. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oakes RS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Fish EN, et al. Detection and quantification of left atrial structural remodeling with delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2009;119:1758–1767. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.811877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Platonov PG, Mitrofanova LB, Orshanskaya V, Ho SY. Structural abnormalities in atrial walls are associated with presence and persistency of atrial fibrillation but not with age. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2225–2232. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamaguchi T, Otsubo T, Takahashi Y, Nakashima K, Fukui A, Hirota K, et al. Atrial structural remodeling in patients with atrial fibrillation is a diffuse fibrotic process: evidence from high-density voltage mapping and atrial biopsy. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:e024521. 10.1161/JAHA.121.024521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: executive summary. J Arrhythm 2017;33:369–409. 10.1016/j.joa.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neuberger HR, Schotten U, Verheule S, Eijsbouts S, Blaauw Y, van Hunnik A, et al. Development of a substrate of atrial fibrillation during chronic atrioventricular block in the goat. Circulation 2005;111:30–37. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151517.43137.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saito T, Asai K, Sato S, Takano H, Mizuno K, Shimizu W. Ultrastructural features of cardiomyocytes in dilated cardiomyopathy with initially decompensated heart failure as a predictor of prognosis. Eur Heart J 2015;36:724–732. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mary-Rabine L, Albert A, Pham TD, Hordof A, Fenoglio JJ Jr, Malm JR, et al. The relationship of human atrial cellular electrophysiology to clinical function and ultrastructure. Circ Res 1983;52:188–199. 10.1161/01.RES.52.2.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ho SY, Ernst S. Anatomy of Cardiac Electrophysiologists: A Practical Handbook. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Cardiotext Publishing; 2012, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hall B, Jeevanantham V, Simon R, Filippone J, Vorobiof G, Daubert J. Variation in left atrial transmural wall thickness at sites commonly targeted for ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2006;17:127–132. 10.1007/s10840-006-9052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glashan CA, Androulakis AFA, Tao Q, Glashan RN, Wisse LJ, Ebert M, et al. Whole human heart histology to validate electroanatomical voltage mapping in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2867–2875. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marcus JT, DeWaal LK, Gotte MJ, Geest RJ, Heethaar RM, Rossum AC. MRI-derived left ventricular function parameters and mass in healthy young adults: relation with gender and body size. Int J Card Imaging 1999;15:411–419. 10.1023/A:1006268405585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spach MS, Dolber PC. Relating extracellular potentials and their derivatives to anisotropic propagation at a microscopic level in human cardiac muscle. Evidence for electrical uncoupling of side-to-side fiber connections with increasing age. Circ Res 1986;58:356–371. 10.1161/01.RES.58.3.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heider F, Walsh S, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 2009;324:98–102. 10.1126/science.1164680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nicolás-Ávila JA, Lechuga-Vieco AV, Esteban-Martínez L, Sánchez-Díaz M, Díaz-García E, Santiago DJ, et al. A network of macrophages supports mitochondrial homeostasis in the heart. Cell 2020;183:94–109.e23. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roselli C, Chaffin MD, Weng LC, Aeschbacher S, Ahlberg G, Albert CM, et al. Multi-ethnic genome-wide association study for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet 2018;50:1225–1233. 10.1038/s41588-018-0133-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Linzbach A. Heart failure from the point of view of quantitative anatomy. Am J Cardiol 1960;5:370–382. 10.1016/0002-9149(60)90084-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beltrami AP, Urbanek K, Kajstura J, Yan SM, Finato N, Bussani R, et al. Evidence that human cardiac myocyte divide after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1750–1757. 10.1056/NEJM200106073442303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quaini F, Urbanek K, Beltrami AP, Finato N, Beltrami CA, Nadal-Ginard B, et al. Chimerism of the transplanted heart. N Engl J Med 2002;346:5–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa012081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chimenti C, Kajstura J, Torella D, Urbanek K, Heleniak H, Colussi C, et al. Senescence and death of primitive cells and myocytes lead to premature cardiac aging and heart failure. Circ Res 2003;93:603–613. 10.1161/01.RES.0000093985.76901.AF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olivetti G, Melissari M, Capasso JM, Anversa P. Cardiomyopathy of the aging human heart. Myocyte loss and reactive cellular hypertrophy. Circ Res 1991;68:1560–1568. 10.1161/01.RES.68.6.1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin J, Lopez EF, Jin Y, van Remmen H, Bauch T, Han HC, et al. Age-related cardiac muscle sarcopenia: combining experimental and mathematical modeling to identify mechanisms. Exp Gerontol 2008;43:296–306. 10.1016/j.exger.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pashakhanloo F, Herzka DA, Ashikaga H, Mori S, Gai N, Bluemke DA, et al. Myofiber architecture of the human atria as revealed by submillimeter diffusion tensor imaging. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016;9:e004133. 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huo Y, Gasper T, Schonbauer R, Wojcik M, Fiedler L, Roithinger FX, et al. Low-voltage myocardium-guided ablation trial of persistent atrial fibrillation. NEJM Evid 2022;1. 10.1056/EVIDoa2200141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sato S, Kitamura H, Adachi A, Sasaki Y, Ishizaki M, Wakamatsu K, et al. Reduplicated basal lamina of the peritubular capillaries in renal biopsy specimens. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol 2005;37:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miyazawa K, Ito K, Ito M, Zou Z, Kubota M, Nomura S, et al. Cross-ancestry genome-wide analysis of atrial fibrillation unveils disease biology and enables cardioembolic risk prediction. Nat Genet 2023;55:187–197. 10.1038/s41588-022-01284-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mezache L, Struckman HL, Greer-Short A, Baine S, Gyorke S, Radwanski PB, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes atrial arrhythmias by inducing acute intercalated disk remodeling. Sci Rep 2020;10:20463. 10.1038/s41598-020-77562-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Polontchouk L, Haefliger JA, Ebelt B, Schaefer T, Stuhlmann D, Mehlhorn U, et al. Effects of chronic atrial fibrillation on gap junction distribution in human and rat atria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:883–891. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01443-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nattel S, Guasch E, Savelieva I, Cosio FG, Valverde I, Halperin JL, et al. Early management of atrial fibrillation to prevent cardiovascular complications. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1448–1456. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andrade JG, Wells GA, Deyell MW, Bennett M, Essebag V, Champagne J, et al. Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2021;384:305–315. 10.1056/NEJMoa2029980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.