Abstract

Ginsenosides are bioactive components of Panax ginseng with many functions such as anti-aging, anti-oxidation, anti-inflammatory, anti-fatigue, and anti-tumor. Ginsenosides are categorized into dammarane, oleanene, and ocotillol type tricyclic triterpenoids based on the aglycon structure. Based on the sugar moiety linked to C-3, C-20, and C-6, C-20, dammarane type was divided into protopanaxadiol (PPD) and protopanaxatriol (PPT). The effects of ginsenosides on skin disorders are noteworthy. They play anti-aging roles by enhancing immune function, resisting melanin formation, inhibiting oxidation, and elevating the concentration of collagen and hyaluronic acid. Thus, ginsenosides have previously been widely used to resist skin diseases and aging. This review details the role of ginsenosides in the anti-skin aging process from mechanisms and experimental research.

Keywords: ginsenosides, anti-skin disorders, skin aging, protopanaxadiol type, protopanaxatriols type

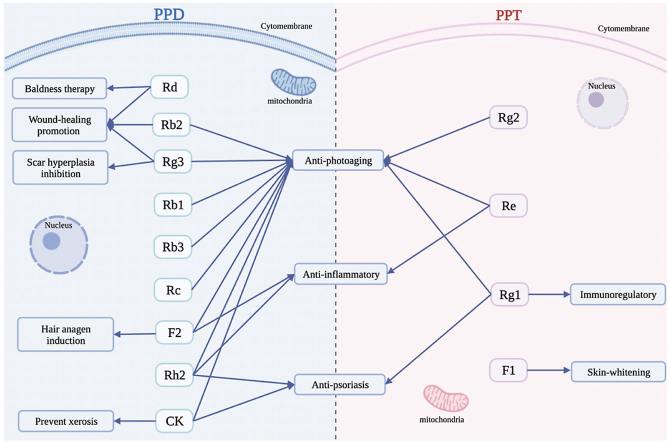

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The skin is one of the most complex organs on the body, covering the entire surface of the body and exposed to the outside environment [1]. The number of patients with skin problems such as skin aging and inflammation increases annually [2]. Skin aging is a multifactorial process influenced by internal and external factors. Internal factors are primarily determined by genetics predisposition, while external factors, including UVB exposure, can lead to the release of free radicals and various reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3,4]. The appearance of free radicals indirectly increases the activity of matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) in the dermis, leading to the breakdown of collagen and elastic fibers, resulting in skin loss of elasticity, wrinkles, scaling, dryness, and pigment abnormalities [[5], [6], [7]]. While the skin possesses enzymatic antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH), to protect it from ROS and free radicals, exposure to UVB can depletes of SOD and GSH, making skin more vulnerable to damage [8,9]. The negative impact of skin aging on physical health can lead to panic and social discrimination [10]. At present, the prevention and treatment of skin aging primarily rely on the external application of cosmetics. Functional components extracted from traditional Chinese herbs, such as ginsenosides and polysaccharides, have been reported to effectively intervene or treat skin aging [11]. For instance, polysaccharides extracted from Cordyceps cicadae have demonstrated significant antioxidant and anti-aging activities by up-regulating catalase, GSH and SOD1 [12].

Agrocybe aegerita polysaccharides scavenged hydroxyl and DPPH accumulation at a concentration of 4500 μg/mL, maintaining the skin collagen of aging mice in vitro, and elevated the activity of SOD and catalase in vivo [13]. It has been shown that ginsenosides extracted from ginseng activate various signaling pathways, including FOXO/DAF-16, NRF2/SKN-1, and SIRT1/SIR 2.1, which are involved in anti-oxidative activity and longevity [14].

The primary bioactive ingredients in ginseng are known as ginsenosides, which consist of four hydrophobic rings steroid-like structures with hydrophilic sugar moieties [15,16]. Ginsenosides are classified into dammarane, oleanene, and ocotillol type tricyclic triterpenoids based on their aglycon structure. Within the dammarane type, there are two subtypes known as protopanaxadiol type (PPD) and protopanaxatriols type (PPT), which differ in position and number of sugar substituents attached to the steroid backbone [17]. The PPD subtype includes various ginsenosides, such as Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, F2, Rg3, Compound K (CK), and Rh2, each with different sugar moieties linked to C-3 and C-20. PPD is derived from different ginsenosides by hydrolyzing sugar moieties. Glycosylated ginsenosides, including Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, and Rd, account for over 90% of total ginsenosides and are often regarded as the major ginsenosides responsible for angiogenic activity due to their similar structure to cholesterol and steroid hormones [18,19]. PPD plays an essential role in anti-photoaging, alleviating stress aging, prompt wound-healing, and anti-inflammatory. On the other hand, PPT includes F1, Rg1, Rg2, and Re, with different sugar moieties linked to C-6 and C-20 [20]. PPT ginsenosides play roles in anti-aging, immunoregulatory, and skin-whitening by hydrolyzing different sugar moieties from C-6 and C-20.

Based on the stereochemistry of the chiral carbon C-20, PPD and PPT types of ginsenosides exist in S- and R- forms. Studies have shown that these ginsenosides exhibit various biological effects, including antitumor, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-dementia, anti-aging, anti-fatigue, anti-oxidative, anti-viral, morphine-dependence attenuating, wound, and ulcer healing activity [[21], [22], [23]]. In addition, besides natural aging, extrinsic factors such as UVB radiation can cause facial wrinkles. Therefore, functional cosmetics and foods are needed to slow down the aging process [24].

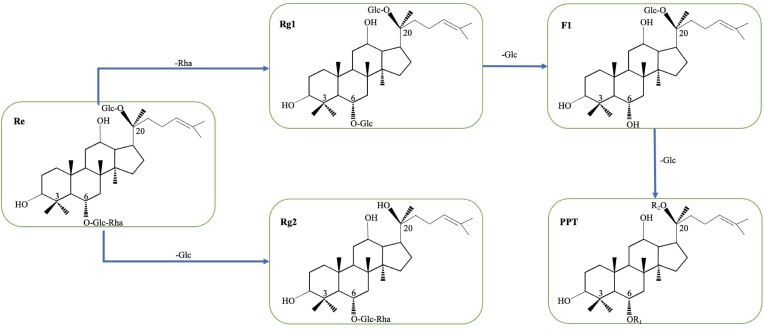

2. PPD

There are different sugar moieties linked to C-3 and C-20 in PPD. The majority of PPD ginsenosides contain glucose at C-3 inner and outer position, with a few containing xylose at the C-3 site. The sugars moieties at C-20 can be glucose, arabinopyranose, xylose, or arabinofuranose. Ginsenoside Rd is derivatives deglycosylated from Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, and Rc by hydrolyzing glucose, arabinopyranose, xylose, and arabinofuranose at C-20. The deglycosylated ginsenosides, such as F2, Rg3, CK, and Rh2, exhibit greater pharmacology activity compared to glycosylated ginsenosides, due to their smaller size and higher permeability across the cell membrane, F2 and Rg3 are produced by specifically hydrolyzing glucose linked to C-3 and C-20 from Rd using microorganisms or enzyme methods, while CK, and Rh2 are produced by specifically hydrolyzing glucose linked to C-3 on F2 and Rg3, respectively (Fig. 1). PPT is a saponins of panaxadriol. In the current study, by hydrolyzing different kinds or amounts of sugar moieties, PPD is isolated from ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, and Rd. Studies have demonstrated that PPD inhibit skin photo-aging, alleviate stress aging, promotes wound-healing, and reduces inflammation by up- or down-regulating specific molecules or pathways (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of plausible biotransformation of PPD.

Table1.

The Characteristics of Ginsenosides.

| Ginsenosides | Type | Pharmacological activities on skin | Molecular Targets | Level | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rb1 | PPDs | Alleviate stress aging | hormone | Animal level | [25] |

| Anti-aging | |||||

| SOD/SOD1, MDA, ROS, MMP-2, GSH | Cellular level | [[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]] | |||

| Rb2 | PPDs | Anti-photoaging | ROS, MMP-2, GSH, SOD | Cellular level | [[37], [38], [39]] |

| Wound-healing promotion | Fn, FnR, keratin 5, keratin 14 | Cellular level | [40] | ||

| Rb3 | PPDs | Anti-photoaging | ROS, MMP-2, MMP-9, GSH, SOD | Cellular level | [41] |

| Rc | PPDs | Anti-photoaging | ROS, MMP-2, MMP-9, GSH, SOD, caspase-14 | Cellular level | [[42], [43]] |

| Rd | PPDs | Wound healing promotion | p-ERK, p-AKT, cAMP, CREB | Cellular & Animal level | [44] |

| Baldness therapy | P63 | Animal level | [45] | ||

| F2 | PPDs | Anti-aging | MMP-1, IL-6 | Cellular level | [[46], [47]] |

| Hair anagen induction | β-catenin, LEF-1, DKK-1, TGF-β, SCAP | Animal level | [[48], [49]] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | IL-17, ROS | Animal level | [50] | ||

| Rg3 | PPDs | Anti-photoaging | SOD, NO, ROS, MMP-2, PRDX3, Sirt3, mTOR, PI3K/AKT | Cellular level | [[54], [55]] |

| Fatigue resistance | SOD, SIRT1, cell communication, skin regeneration | Animal level | [56] | ||

| Wound healing promotion | VEGF | Animal level | [[57], [58]] | ||

| CK | PPDs | Prevent xerosis | HAS2 | Animal level | [61] |

| Anti-photoaging | MMP-1, COX2, HAS1, HAS2 | Cellular level | [[62], [63], [65]] | ||

| Anti-psoriasis | REG3A, IL-36g | Cellular level | [67] | ||

| Rh2 | PPDs | Anti-photoaging | ROS, MMP-2, MMP-9 | Cellular level | [69] |

| Anti-inflammatory | NO, PGE2 | Cellular level | [70] | ||

| Anti-psoriasis | VEGF-A, inflammatory factors | Animal level | [71] | ||

| Re | PPTs | Anti-aging | ROS, MMP-2, MMP-9, GSH, SOD, caspase-14 | Cellular level | [[74], [75]] |

| Anti-inflammatory | NO, MDA, IL-β, TNF-α | Animal level | [76] | ||

| Rg1 | PPTs | Anti-aging | P53, P21, P16, caspase 3 and Bax, Bcl-2, Sirt3, SOD2; SOD2, SIRT3, SIRT1, FOXO3; P16, P21, ROS, NLRP3, IL-2 | Cellular & Animal level | [[77], [78], [79], [80]] |

| Immunoregulatory | INF-γ, IL-10, TNF-α IL-2 | Animal level | [[81], [82]] | ||

| Anti-psoriasis | IL-23, 22, 17A, 1β, TNF-α, NF-κB | Animal level | [83] | ||

| Rg2 | PPTs | Anti-photoaging | ROS, MMP-2, GSH, SOD, P53, Gadd45a, p21 | Cellular level | [[84], [85]] |

| F1 | PPTs | Inhibit melanin secretionSkin-whitening | cAMP, PI3K, GTPase | Cellular level | [87] |

| dendrite retraction | Cellular & Clinical level | [88] | |||

| IL-13, DCT | Clinical level | [89] |

2.1. Ginsenoside Rb1

Ginsenoside Rb1, a glycosylated PPD type ginsenoside with two sugars linked to C-3 and two sugars linked to C-20, is the major active constituent of American ginseng. Studies have demonstrated the anti-aging effects of ginsenoside Rb1 at both animal and cell levels. For example, at animal level, treatment with at least 2.5 mg/kg ginsenoside Rb1 has been shown to restore plasma androgen or estrogen levels and increase corticosterone levels, thus alleviating body aging caused by stress in Kunming rats [25]. At cellular level, the hyaluronan acid synthase 2 (HAS2) enzyme is essential for production of hyaluronic acid (HA) and improving skin hydration. 20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol (20GPPD) is the major ingredient of ginsenoside Rb1, which has been shown to increase HAS2 expression by phosphorylating ERK and AKT signaling in human keratinocytes in a dose-dependent manner in vitro [26]. During aging, cells begin to lose their growth and division ability, accompanied by ROS accumulation. Ginsenoside Rb1 has been shown to prevent cellular senescence by regulating redox status. For instance, pre-treatment of HUVECs with Rb1 increased SOD1 mRNA and protein levels in a dose-dependent manner, and suppressed H2O2-induced ROS production and malondialdehyde (MDA) content [27]. Sirtuins (Sirts) consisted of 7 NAD+-dependent deacetylases. Among these, Sirt1 and Sirt3, as the predominant deacetylases, were closely associated with senescence and oxidative stress. Researchers indicated that treatment with 20 μmol/L ginsenoside Rb1 for 30 minutes significantly prevents endothelial senescence and dysfunction by stimulating Sirt1 in HUVEC [28,29]. Additionally, ginsenoside Rb1 possesses skin anti-photoaging abilities [30]. UVB causes photoaging for its cumulative DNA damage in the upper dermis in human dermal keratinocytes [31]. Rb1 was reported to accelerate the clearance of damaged DNA induced by UVB to prevent HaCat cells from apoptosis [32].

2.2. Ginsenoside Rb2

Ginsenoside Rb2 is a 20(S)-PPD glycoside that can be extracted from ginseng. It contains two glucose molecules attached to C-3, one glucose molecule, and one α-l-arabinopyranosidic linkage attached to the C-20 outer position of the aglycone. Rb2 is a predominant ginsenoside found in ginseng and has been associated with various therapeutic effect, such as in anti-aging, wound-healing promotion, anti-diabetic, antimetastatic, fibrinolytic, antiviral, and antioxidative [[33], [34], [35], [36]]. At the cellular level, Korean studies have showed that UVB irradiation at 70 mJ/cm2 significantly enhances ROS levels by 5.9-fold compared to the non-irradiated HaCat cells. Ginsenoside Rb2 has been found to play a crucial role in anti-photoaging, as it can suppress UVB-induced ROS enhancement by 86.5%, 71.4%, and 62.9%, and decreased the expression of MMP-2 in a dose-dependent manner in human dermal keratinocytes [37]. The target sequence for Rb2-specific induction was located in the proximal part of the SOD1 gene promoter (−305 to −55), consisting of several transcription factor binding sites. The functional AP2 binding sites were located in the proximal part (−305 to −74) of the SOD1 promoter region. Thus, Rb2 remarkably activated the SOD1 gene, encoding Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase, via the transcription factor AP2, which is involved in response to oxidative stress [38]. Another study demonstrated that Rb2 is involved in the protective activity against aging by scavenging UVB irradiation-induced ROS, down-regulating MMP-2 protein level, and elevating the content of GSH and SOD in human dermal fibroblast cells [39]. It has been reported that Rb2 could increase the expression of epidermal growth factor and its receptor, fibronectin, and its receptor, keratin 5/14, in a concentration-dependent manner by stimulating epidermis formation. Rb2 also improves wound healing in a dose-dependent manner in raft-cultured keratinocytes [40].

2.3. Ginsenoside Rb3

Ginsenoside Rb3 is one of the main active components of PPT-type ginsenosides isolated from ginseng, which has been shown to possess skin anti-photoaging activity. Treatment of 70 mJ/cm2 UV-B-radiated HaCat cells with various concentrations of Rb3 (5, 12, 30 μM) reduced ROS level to 79.4%, 65.2%, and 32.6%, respectively, as well as a concentration-dependently decrease in MMP-2 and -9 expression. Furthermore, Rb3 was found to increase total GSH by 1.6-, 2.0-, 2.4-fold and SOD levels by 2.7-, 4.1-, and 4.6-fold, indicating that it possesses anti-aging effects at the cellular level [41]. However, to date, there is a lack of animal or clinical studies investigating the efficacy of Rb3 as an anti-aging or treatment for skin disorders.

2.4. Ginsenoside Rc

Ginsenoside Rc, a major PPD-type ginsenosides derived from Panax ginseng, has been extensively researched for its effects on diabetes, cancer, and immune system diseases. However, there are limited reports on its effects on skin disorders [42]. Rc is a glycosylated ginsenoside with two glucose molecules at the C-3 position and one glucose and one arabinofuranose molecule at the C-20 position. Rc protects against UVB-mediated skin aging through antioxidant activity. For example, at the cellular level, treatment with Rc (0, 5, 12, 30 μM) suppressed UVB-induced production of ROS (to 65.7%, 45.6%,34.6%) and MMP-2 (to 39.3%, 21%, 8.0%), −9 (to 27.8%, 21.1%, 15.4%), while enhanced total GSH level (by 1.9-, 2.0-, 2.3-fold), SOD activity (by 4.5-, 5.4-, 7.8-fold), and caspase-14 expression (by 2.0-, 2.9-, and 3.7-fold) in human dermal keratinocytes under 70 mJ/cm2 UVB radiation [43].

2.5. Ginsenoside Rd

Ginsenoside Rd belongs to the PPD type of ginsenosides derived from Panax ginseng leaves. Rd has two glucose molecules at C-3 and one glucose molecule at C-20, which can be obtained by glycoside hydrolysis at different positions of Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, and Rc. Rd has a remarkable promoting effect on wound healing and hair growth. At the cellular level, Rd was found to promote wound healing by concentration-dependently (0.1, 1, 10 μM), accelerating keratinocyte progenitor cell proliferation and migration by improving cAMP generation and cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation, thus elevating the level of collagen type I levels. In vivo, Rd demonstrated wound healing property in the female hairless mice with epidermal wounds caused by laser burns [44]. Similarly, C57BL/6 mice, topical application of a 20% ethanol and methanol mixture (9:1) containing 5 mg/mL of Rd and a daily dose of 300 mg/kg body weight (1.5 ml/day) of Rd for 35 days, accelerated cell proliferation in the anagen and telogen phases of hair follicles, possibly by upregulating P63 expression in a matrix and outer root sheath [45].

2.6. Ginsenoside F2

Ginsenoside F2 belongs to the minor ginsenosides that are present at a tiny concentration in ginseng. F2 was enzymatically hydrolyzed from PPD with two glucose molecules at C-3 and one at C-20. Ginsenoside F2 effectively kept skin hydrated, prevented the skin aging, and promoted hair follicle growth to a large extent. At the cellular level, F2 significantly reduced MMP-1 expression by 64% and 48% at 1 μg/mL concentration and 10 μg/mL, respectively, in cultured human dermal fibroblasts. However, cytotoxicity was observed at a high dose of 10 μg/mL [46]. The mixture of 10 μg/mL ginsenoside F2 and 10 μg/mL α-gastrodin exhibited a more substantial anti-aging effect since the expression of MMP-1 and interleukin-6 (IL-6) was significantly inhibited by 18% and 65%, and promoted procollagen type I increased by 200% in UVB-irradiated human dermal keratinocytes [47]. At the animal level, F2 also exhibits the hair anagen induction effects. Compared with the finasteride-induced hair growth mice group, ginsenoside F2 increased the hair follicle growth rate by 20% through up-regulating β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), which were considered the major factor and down-regulating DKK-1 in hair growing phase at the concentration of 0.1 μM. Meanwhile, an increasing number of hair follicles and thicker epidermis were observed in F2 treatment C57BL/6 mice group [48]. The conclusions were in accord with Shin et al, who clarified that F2 promotes hair anagen phase by reducing the expression of TGF-β and cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) in C57BL/6 mice [49].

Researchers established an inflammatory model that used 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) on the mouse ear surface. They found that treatment with F2 markedly decreased ear thickness, skin punch weight, and inflammatory response. Besides, treatment of ginsenoside F2 respectively inhibits infiltration of IL-17 and generation of ROS in γδ T cells and neutrophils, indicates that ginsenoside F2 application may be a potential treatment for skin inflammation [50].

2.7. Ginsenoside Rg3

Ginsenoside Rg3 is a hydrolysis product of ginsenoside Rd. Raw ginseng is steamed at a high temperature to be processed into red ginseng to stimulate its pharmacological activity. During the steaming time, PPD type ginsenosides such as Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rb3, and Rd are bio-conversed into 20(S)-Rg3, and then the S configuration is converted to the R form. Two stereoisomeric forms were found in ginseng products, 20(S)-Rg3 and 20(R)-Rg3, which are epimers based on the –OH geometrical position on C-20 in the molecular structure. When Rg3 is considered an antioxidant agent, R form should be used due to its greater antioxidant effect. Researchers modeled oxidative stress in mice by intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide to observe the free radical scavenging capacity of 20(S)-Rg3 and 20(R)-Rg3. The 20(R)-Rg3 configuration of Rg3 exhibited significantly higher antioxidant activities than 20(S)-Rg3. At the cellular level, 20(R)-Rg3 increased catalase, SOD, and lysozyme activities, reduced xanthine oxidase production and the expressions of malondialdehyde and nitric oxide [51]. However, some researchers take a different view, they argue that treatment with 20(S)-Rg3reverses human dermal fibroblasts senescence by down-regulating ROS and MMP-2 production, and increasing peroxiredoxins 3 (PRDX3) by 22.5-fold which were ROS-scavenging antioxidant enzymes [52,53]. The treatment of Rg3 from 1 to 10 μm on human dermal fibroblasts cells elevated the expression of proteins associated with the extracellular matrix (ECM), and cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, Rg3 plays a significant role in protecting mitochondrial dysfunction as it could suppress the release of cytochrome-c and inhibits UV-induced apoptosis [54]. Rg3 plays its fatigue resistance role in aged rats by increasing the concentration of SOD of skeleton and elevating SIRT1 deacetylase activity [55]. Rg3 reduced the ROS expression level and increased NAD+/NADH ratio in a concentration-dependent manner, and downregulated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt via inhibiting mTOR by cell cycle regulators in human senescent dermal fibroblasts to against aging [56]. In addition, at the animal level, Rg3 could promote wound healing by promoting cell communication and skin regeneration in rabbit ear hypertrophic scarring model, as well as inflammation inhibition and VEGF expression down-regulation, therefore significantly inhibiting scar hyperplasia on rat back skin [57,58].

2.8. Ginsenoside compound K (CK)

Ginsenoside CK is a major deglycosylated metabolite form of ginsenosides F2, which is more bioavailable and soluble than the parental ginsenosides [59]. CK as a major hydrolysate was firstly isolated from a mixture of ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, and Rc with biotransformation approaches by Japanese researchers in 1972 [60]. Numerous studies have shown that CK prevents skin from aging by anti-UVB radiation and moisturizing and delays skin inflammation by regulating immunity. For example, treatment with CK on hairless mouse skin resulted in the increase of hyaluronan, thus elevating HAS2 content in epidermis and dermis 3-fold than untreated skin, which suggests that the application of CK might prevent xerosis of human or animal skin [61]. Moreover, CK alleviated the cytotoxicity of UVB-radiation and prevented UVR-induced apoptosis at doses of 5,15,45 μg/mL, and the higher the concentration, the better the effect on human keratinocyte cell line [62]. In fibroblasts radiated with UVA, the generation of type I collagen was inhibited, while 1μm CK upregulated the generation of type I collagen by 68% and decreased the protein level of MMP-1 by 77%, respectively [63], similar to previous papers that reported CK could alleviate wrinkles and xerosis [64], suggested CK is a potential agent to prevent and treat photoaging of the skin. Filaggrin is essential for skin water retention since its responsible for the formation of a protein-lipid matrix. CK elevated skin moisture and prevented photoaging from UVB-radiation by decreasing the activity of MMP-1 and cyclooxygenase-2, recovering collagen type I expression, while elevating the expression of filaggrin, transglutaminase, HAS-1, and -2 in HaCat cells [65]. The results above suggest that CK could be used in anti-aging cosmetics. Furthermore, psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder. Accumulating studies indicated that the initiation and persistence of psoriasis might be driven by the proliferation of keratinocytes [66]. Ginsenoside CK inhibited the expression of IL-36γ-induced regenerating islet-derived protein 3-alpha (REG3A) in human keratinocytes at a minimum concentration of 400 ng/ml in human keratinocytes, thereby inhibiting the proliferation of keratinocytes in vitro. In addition, 1% ginsenoside CK cream alleviated imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like hyperkeratosis possibly by inhibiting IL-36γ-induced REG3A expression in IMQ-induced psoriasis mouse model, suggests that ginsenoside CK might be a clinical treatment of topical application in the treatment of psoriasis [67].

2.9. Ginsenoside Rh2

Although ginseng contains only tiny amounts of Rh2, PPD-type ginsenosides, including Rg3, Rb1, Rb2, and Rc, are transformed to Rh2 by acids and human intestinal bacteria [68]. Rh2 is characterized by antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging activities. Rh2 exists as two stereoisomeric forms, 20(R)-Rh2 and 20(S)–Rh2, researchers found that concentrations of 5, 12, 30 μmol 20(S)–Rh2 were able to decrease the production of ROS to 94.9%, 53.8%, 29.9% in keratinocyte cells under 70 mJ/cm2 UV-B irradiation, but 30 μmol 20(S)–Rh2 is already cytotoxic on HaCat cells. Both 20(S)–Rh2 and 20(R)-Rh2 exhibit anti-photoaging activities by down-regulation of UVB-induced MMP-2 activity in a dose-dependent manner, but 20(R)-Rh2 has a weaker effect [69]. 20(R)-Rh2, as the minor stereoisomer of ginsenoside Rh2, was confirmed to possess anti-inflammatory activity by down-regulating pro-inflammatory mediators, such as NO and prostaglandin F2 (PGE2), which leads to a numbers of inflammatory states. Treatment with 50 μm 20(R)-Rh2 on RAW264.7 macrophage cells diminished the production of nitric oxide (NO) and PGE2 by 45% and approximately 75%, and decreased the ROS levels to 33%, which demonstrated antioxidative activity, MMPs reduced collagen content contributed to aging and wrinkling, treatment with 20(R)-Rh2 at doses of 10, 30, 50 μm inhibited the activity of MMP-9 in a dose-dependent way in the stimulated macrophages. However, in human HaCat cells, 20(R)-Rh2 decreases ROS level to 77% at a concentration of 25 μm, and decreases the activity of MMP-2, MMP-9, in spite of the fact that not in a dose-dependent way, showing the anti-aging impact of Rh2 [70]. In addition, Rh2 also showed potent anti-inflammatory activity. Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by epidermal hyperplasia and inflammatory infiltrate. Ginsenoside Rh2 was noted to possess the effect of anti-psoriasis. Rh2 at different concentrations (0.01, 0.1 and 1mg/ mL) was injected to the skin grafts in mice. The acanthosis and papillomatosis index were decreased in concentration-dependent fashion. In addition, Rh2 dose-dependently decreased T lymphocyte rate and VEGF level in the psoriasis mice model [71]. The anti-inflammatory effect of Rh2 was also observed in the mice model. Rh2 has poor clinical availability due to the extremely low oral availability. 20(S)–Rh2 was sulfated with chlorosulfonic acid and pyridine method, and the new sulfated derivatives possess stronger anti-inflammatory effects than parental by suppressing inflammatory factors and mediators in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. The combination of ciprofloxacin and Rh2 dedicated a greater synergism against both methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, thus significantly improving their anti-inflammatory effect [72,73].

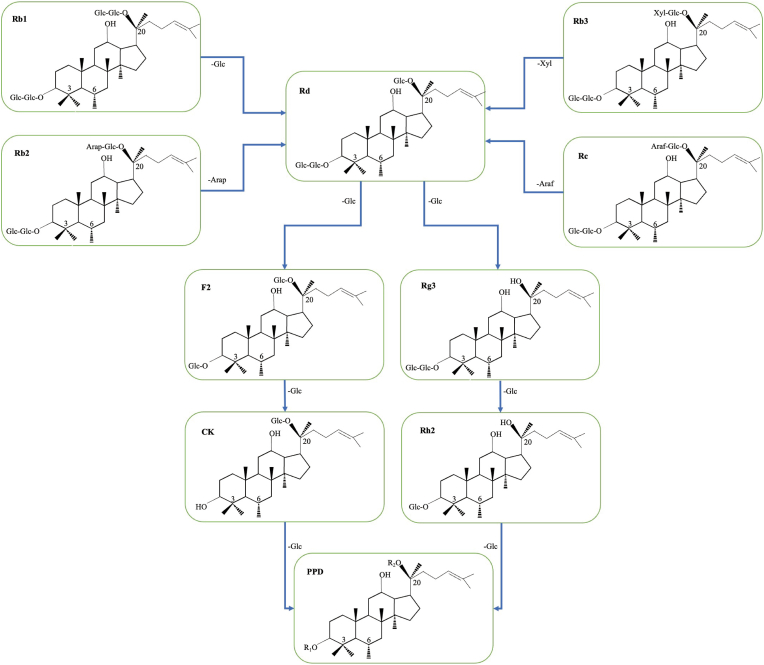

3. PPT

Most PPT-type of ginsenosides contain different sugar moieties linked to C-6 and C-20, and a few contain diverse sugar moieties at C-3. The C-6 inner sugar may be glucose and xylose, the outer sugar may be glucose, xylose, or rhamnose, while the C-20 sugar maybe glucose, xylose and arabinose. PPT is a saponins of panaxatriol, and in the present study, PPT-type ginsenoside is derivatived from ginsenosides Re, and Rg1 by hydrolyzing different kinds or amount of sugar moieties. Ginsenoside Rg1 and Rg2 are derivatives deglycosylated from Re by hydrolyzing rhamnose and glycose at C-6 and C-20, respectively. F1 was generated by glucose hydrolysis at C-6 of Rg1 (Fig. 2). PPT play an essential role in anti-aging, immunoregulatory, and skin-whitening by regulating the expression levels of specific molecules or pathways (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of plausible biotransformation of PPT.

3.1. Ginsenoside Re

Ginsenoside Re (Re) is a kind of glycosylated ginsenoside with one glucose molecule and one rhamnose molecule at C-6, and one glucose molecule at C-20 outer position of the aglycone. Re exhibits a function of antioxidant and antioxidant-related activities in different kinds of cell types. For example, in HaCat cells, ginsenoside Re at a dose of 30 μM elicits its anti-photoaging activity by suppressing the generation and production of UVB-induced ROS to 25.6% and attenuating MMP-2, -9 secretion to 30.7%, 32.1%, respectively. Meanwhile, it elevated the GSH contents to 3.8-fold and SOD activity to 3.1-fold [74]. Furthermore, treatment with 30 μM Re in human dermal keratinocytes possibly enhances skin barrier function by elevating cell envelope formation, up-regulating the production of filaggrin in a concentration-dependent manner, which is essential for water retention in the stratum corneum activating caspase-14 to inhibit inflammatory reactions [75].

Exposure to TPA on the ear of BALB/C mice increases ear thickness and skin water retention, which represents skin irritation and local inflammation. Treatment with 5mg/kg Re significantly inhibits the expression of the inflammatory factors such as NO, MDA, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Topical application of Re at a dose of 250 μg/mL significantly inhibits the increase in ear thickness and leads to a 30% decrease in water retention [76]. To sum up, it can be seen that ginsenoside Re possesses antioxidant, anti-aging, and anti-inflammatory effects on the skin.

3.2. Ginsenoside Rg1

Ginsenoside Rg1 belongs to PPT type ginsenosides produced by hydrolysis of rhamnose at C-6 of Re. Rg1 has one glucose molecule at C-6 and one glucose molecule at C-20, which is the major active ingredient of Panax ginseng with neuroprotective, anti-aging, anti-injury, anti-oxidation, and strengthening the immune system. At the cellular level, long-term exposure of dermal fibroblasts to UVB leads to G1 arrest, the sign of senescence. P53/P21 and P16/Rb pathways have been approved to be associated with the progression of senescence [77]. Researchers found that Rg1 did not show the cytotoxicity of HaCat and HSFs cells up to 25 μg/mL and significantly decreased the UVB-induced (15 mJ/cm2) G1 phase arrest from 80.29% to 57.18% in HaCat cells and 88.63% to 70.38% in HSFs cells, respectively. Treatment with Rg1 down-regulated the protein level of P16 and P53 by 1.8- and 2.2-fold in HaCat cells and down-regulated the protein level of P16 and P21 by 1.7- and 3.5-fold in HSFs cells, indicating the anti-aging effect [78]. Ginsenoside Rg1 markedly inhibited apoptosis by decreasing caspase-3 and Bax mRNA expressions and increasing Bcl-2 level. Moreover, treatment with Rg1 on the D-galactose-induced aging rat model at the animal level elevated the Sirt3 and SOD2 levels compared to the non-treated group, confirming its anti-aging effects [79]. Treatment of Rg1 on γ-ray-radiation-induced aging mouse model exerts anti-aging effects through elevating the mRNA and protein level of SIRT, SIRT3, and increasing their downstream molecule FOXO3, SOD2 from protein level, respectively [80]. Treatment with Rg1 reversed UVB-induced hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, sponge-like edematization, and inflammatory cell infiltration in the papillary layer of the BalB/c mouse dermis. For example, 3.0 mg/100 μL Rg1 also exhibits the immunoregulatory capacity on mice for attenuating the UVB-radiation induced expression of IFN-γ, IL-10, TNF-α by 19.7%, 25.7%, and 20%, respectively in BalB/c mouse [81]. In addition, researchers found that treatment of Rg1 promoted lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 production in aging rats and improved T cell function against aging [82]. Treatment of Rg1 (50 mg/kg) reduced skin thickness and MDA level and increased the activity of SOD in IMQ-induced mice psoriasis model. Rg1 also exhibited anti-inflammatory capacity by downregulating IL-23, 22, 17A, 1β, and TNF-α expression and NF-κB signaling pathway, indicating the potential function against psoriasis [83]. Ginsenoside Rb1 seems to have the ability to interfere with nearly all pathways that accelerate the aging process.

3.3. Ginsenoside Rg2

Ginsenoside Rg2 is a hydrolysate of Re with a glucose molecule removed from the C-20 site. It has been reported that Rg2 exists in two epimeric forms, 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg2 [20(S)-Rg2] and 20(R)ginsenoside Rg2 [20(R)-Rg2]. However, only cellular level studies have been reported so far. For example, UVB-irradiated HaCat cells were treated with the two epimers at different concentrations of 5, 12, 30 μM. Of the two epimers, only 20(S)-Rg2 protect skin photoaging from UVB radiation in a concentration-dependent fashion. 30 μM 20(S)-Rg2 is non-cytotoxic and decreases ROS production to 59.5% and MMP-2 to 12.8% while elevating the total GSH by 2.7-fold and SOD by 4.3-fold [84]. Astaxanthin, an antioxidant, decreases ROS levels induced by UVB radiation. COL1A1 (the main structural protein in the extra-cellular space) is degraded by MMPs due to exposure to the injury source. The combination use of astaxanthin and Rg2 at a ratio of 1:5 enhances COL1A1 expression and decreases p-ATM, p-p53, GADD45α, p21, MMP-3, -9, -13 levels in a dose-dependent manner [85].

3.4. Ginsenoside F1

Ginsenoside F1 is a metabolite produced by the hydrolysis of ginsenoside Re and Rg1, with a molecule of glucose at C-20 position [86]. Melanocyte dendrite is one of the essential factors in melanin release, and dendrite retraction enhances the accumulation of pigment in melanocytes, which significantly affects the transfer of pigment. F1 (200 μM) was reported to significantly reduced α-MSH-induced melanin secretion by 60% in B16F10 cell culture medium by reducing cAMP expression, elevating the capacity of PI3K and GTPase, leading to the induction of dendrite retraction and pigmentation [87]. Researchers investigated the effect of F1 on MNT-1/HaCaT co-cultures cells and three-dimensional (3-D) human skin equivalent, demonstrated that F1 suppressed melanosome transfer, leading to dendrite retraction and promotion of skin whitening [88]. Another study found that 8 weeks for the application of a cream containing 0.1% ginsenoside F1 showed a significant whitening effect on human skins of 20 volunteers where was tanned by exposure to ultraviolet light, the possible whitening effect of F1 might be mediated by changing the response of activated epidermal γδ T cells, thus improving the production of IL-13, thus reducing tyrosinase and dopachrome-tautomerase (DCT) mRNA and protein levels, and decrease melanin synthesis activity in human epidermal melanocytes [89].

4. Discussion

It is noteworthy that plants contain numerous chemical components that have proven effective in various applications. These components include polysaccharide, terpenoid compounds, ether compounds, alkaloid, and essential oil, among others [[90], [91], [92], [93]]. Some of these ingredients are commonly utilized as functional materials for skin care products. For instance, the adding of essential oils to cosmetics not only helps prevent microbial infection, but also aids in preserving cosmetic formulations [94]. Polyphenols and polysaccharides exhibit a diverse range of biological activities. Polyphenols possess potent free radical scavenging ability and antibacterial properties against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Polysaccharides have a significant inhibitory effect on tyrosinase and exhibit excellent moisture absorption and retention capabilities, making them ideal for use as active ingredients in cosmetics. However, these components still face challenges in clinical or commercial applications. For example, the skin dose not readily absorb plant polysaccharides as biomacromolecules. Moreover, the identification and development of various phenolic compounds require a considerable amount of time and economic resources [95]. While alkaloids are often utilized as a starting point for drug development, their synthetic basis still necessitates the latest advances in genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics [96]. Similarly, essential oils exhibit promising potential. However, their use is constrained by encapsulation, limited water solubility, and high volatility [97]. Therefore, ginsenosides, a single-structured plant compound with significant functions and a clear target, demonstrate tremendous potential and advantages in the treatment and managing various skin diseases.

Currently, most ginsenoside research is primarily conducted in Southeast Asian countries, such as China, South Korea, and Japan [98]. Many researchers' primary focus is investigating the anti-tumor or immunoregulatory effects of ginsenosides, with product development being driven by these objectives [99,100]. For example, clinical trials have confirmed that Rg1 enhanced the effect of exercise on reducing endothelial progenitor cell aging and tissue inflammation, suggesting that ginsenoside Rg1 is involved in endothelial progenitor cell rejuvenation [101]. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, ginsenosides were found to significantly increase mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number and total antioxidant status and improve fatigue symptoms in postmenopausal women [102]. It is worth noting that the general public widely consumes ginsenosides as functional food or health products [103].

In this review,it has been observed that both PPT-type and PPD-type ginsenosides exhibit remarkable efficacy in treating various skin conditions, including inflammation, and immune-related disorders, as well as exhibiting anti-aging, antioxidative, and skin-whitening properties. Nevertheless, the direct clinical application of ginsenosides for skin diseases treatment remains limited. Furthermore, cosmetic products that use ginsenosides for their skin anti-aging, whitening, and antioxidative effects mainly utilize crude ginseng extracts rather than pure ginsenosides as their primary component [[104], [105], [106]]. This trend may be attributed to the challenges associated with extracting or preparing ginsenosides with a single, well-defined composition, especially for rare saponins such as Rh2, Rg3 and CK. These saponins have extremely low yields in natural ginseng, and the laboratory conversion conditions are limited, which complicates large-scale extraction or industrial production efforts. Consequently, these limitations have hindered ginsenosides' clinical or commercial application in treating skin conditions, developing functional foods, or skincare products that use ginsenosides as the main ingredient. Addressing these challenges remains a critical focus area in the ginsenoside research field.

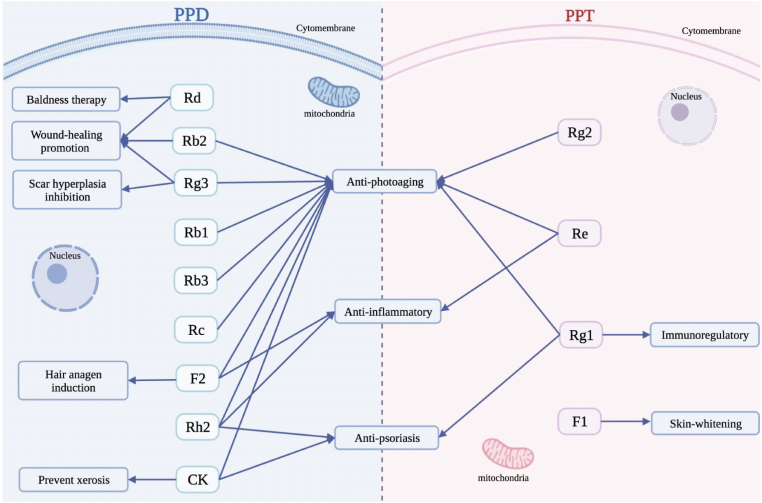

5. Conclusion

This review summarized the anti-dermatosis effects of dammarane-type ginsenosides extracted from Panax ginseng. Dammarane-type ginsenosides, including PPD and PPT, have different sugar moieties linked to different positions. Studies have demonstrated that PPD exhibits biological abilities such as anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, anti-psoriasis, wound-healing promotion, baldness-therapy, scar hyperplasia inhibition, hair anagen induction, as well as xerosis prevention by regulating a series of molecules and enzymes. While PPT have anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, anti-psoriasis, immunoregulatory, and skin-whitening activities by modulating different molecules than PPD (Fig. 3). This review provides a theoretical basis and clinical significance for the treatment of skin disorders using dammarane-type ginsenosides.

Fig. 3.

The functions of ginsenosides in human epidermal cells.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (grant no. YDZJ202201ZYTS021, 20190103086JH).

Contributor Information

Xianling Cong, Email: congxl@jlu.edu.cn.

Miao Hao, Email: miaohao@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Grice E.A., Segre J.A. The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9(4):244–253. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nybaek H., Jemec G.B. Skin problems in stoma patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010 Mar;24(3):249–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu Y., Han J., Jiang C., Zhang Y. Biomarkers, oxidative stress and autophagy in skin aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2020 May;59 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaz V.V.A., Jardim da Silva L., Geihs M.A., Maciel F.E., Nery L.E.M., Vargas M.A. Single and repeated low-dose UVB radiation exposures affect the visual system. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2020 Aug;209 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittayapruek P., Meephansan J., Prapapan O., Komine M., Ohtsuki M. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in photoaging and photocarcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Jun 2;17(6):868. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian L., Bahudhanapati H., Wei S. Extracellular metalloproteinases in neural crest development and craniofacial morphogenesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013 Nov-Dec;48(6):544–560. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.838203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tüter G., Kurtiş B., Serdar M., Aykan T., Okyay K., Yücel A., Toyman U., Pinar S., Cemri M., Cengel A., et al. Effects of scaling and root planing and sub-antimicrobial dose doxycycline on oral and systemic biomarkers of disease in patients with both chronic periodontitis and coronary artery disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2007 Aug;34(8):673–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homma T., Fujii J. Application of glutathione as anti-oxidative and anti-aging drugs. Curr Drug Metab. 2015;16(7):560–571. doi: 10.2174/1389200216666151015114515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valko M., Rhodes C.J., Moncol J., Izakovic M., Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2006 Mar 10;160(1):1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amaro H., Sanchez M., Bautista T., Cox R. Social vulnerabilities for substance use: stressors, socially toxic environments, and discrimination and racism. Neuropharmacology. 2021 May 1;188 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J., Cho S.Y., Kim S.H., Cho D., Kim S., Park C.W., Shimizu T., Cho J.Y., Seo D.B., Shin S.S. Effects of Korean ginseng berry on skin antipigmentation and antiaging via FoxO3a activation. J Ginseng Res. 2017 Jul;41(3):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Zeng T., Li H., Wang Y., Wang J., Yuan H. Structural characterization and hypoglycemic function of polysaccharides from Cordyceps cicadae. Molecules. 2023 Jan 5;28(2):526. doi: 10.3390/molecules28020526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jing H., Li J., Zhang J., Wang W., Li S., Ren Z., Gao Z., Song X., Wang X., Jia L. The antioxidative and anti-aging effects of acidic- and alkalic-extractable mycelium polysaccharides by Agrocybe aegerita (Brig.) Sing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018 Jan;106:1270–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H., Zhang S., Zhai L., Sun L., Zhao D., Wang Z., Li X. Ginsenoside extract from ginseng extends lifespan and health span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2021 Aug 2;12(15):6793–6808. doi: 10.1039/d1fo00576f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metwaly A.M., Lianlian Z., Luqi H., Deqiang D. Black ginseng and its saponins: preparation, phytochemistry and pharmacological effects. Molecules. 2019 May 14;24(10):1856. doi: 10.3390/molecules24101856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang K.S., Lee Y.J., Park J.H., Yokozawa T. The effects of glycine and L-arginine on heat stability of ginsenoside Rb1. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007 Oct;30(10):1975–1978. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L., Zou H., Gao Y., Luo J., Xie X., Meng W., Zhou H., Tan Z. Insights into gastrointestinal microbiota-generated ginsenoside metabolites and their bioactivities. Drug Metab. Rev. 2020;52:125–138. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2020.1714645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C.Y., Zhou R.X., Sun C.K., Jin Y.H., Yu H.S., Zhang T.Y., Xu L.Q., Jin F.X. Preparation of minor ginsenosides C-Mc, C-Y, F2, and C-K from American ginseng PPD-ginsenoside using special ginsenosidase type-I from Aspergillus Niger g.848. J Ginseng Res. 2015 Jul;39(3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piao X.M., Huo Y., Kang J.P., Mathiyalagan R., Zhang H., Yang D.U., Kim M., Yang D.C., Kang S.C., Wang Y.P. Diversity of ginsenoside profiles produced by various processing technologies. Molecules. 2020 Sep 24;25(19):4390. doi: 10.3390/molecules25194390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majeed F., Malik F.Z., Ahmed Z., Afreen A., Afzal M.N., Khalid N. Ginseng phytochemicals as therapeutics in oncology: recent perspectives. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Apr;100:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai L., Gao J., Wei F., Zhao J., Wang D., Wei J. Therapeutic potential of ginsenosides as an adjuvant treatment for diabetes. Front Pharmacol. 2018 May 1;9:423. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L., Virgous C., Si H. Ginseng and obesity: observations and understanding in cultured cells, animals and humans. J Nutr Biochem. 2017 Jun;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Man S., Luo C., Yan M., Zhao G., Ma L., Gao W. Treatment for liver cancer: from sorafenib to natural products. Eur J Med Chem. 2021 Nov 15;224 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y.H., Park H.R., Cha S.Y., Lee S.H., Jo J.W., Go J.N., Lee K.H., Lee S.Y., Shin S.S. Effect of red ginseng NaturalGEL on skin aging. J Ginseng Res. 2020 Jan;44(1):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng Y., Shen L.H., Zhang J.T. Anti-amnestic and anti-aging effects of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rb1 and its mechanism of action. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005 Feb;26(2):143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim T.G., Jeon A.J., Yoon J.H., Song D., Kim J.E., Kwon J.Y., Kim J.R., Kang N.J., Park J.S., Yeom M.H., et al. 20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol, a metabolite of ginsenoside Rb1, enhances the production of hyaluronic acid through the activation of ERK and Akt mediated by Src tyrosin kinase in human keratinocytes. Int J Mol Med. 2015 May;35(5):1388–1394. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salama R., Sadaie M., Hoare M., Narita M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev. 2014;28:99e114. doi: 10.1101/gad.235184.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu D.H., Chen Y.M., Liu Y., Hao B.S., Zhou B., Wu L., Wang M., Chen L., Wu W.K., Qian X.X. Rb1 protects endothelial cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced cell senescence by modulating redox status. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34(7):1072–1077. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song Z., Liu Y., Hao B., Yu S., Zhang H., Liu D., Zhou B., Wu L., Wang M., Xiong Z., et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 prevents H2O2-induced HUVEC senescence by stimulating sirtuin-1 pathway. PLoS One. 2014 Nov 11;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh S.J., Kim K., Lim C.J. Protective properties of ginsenoside Rb1 against UV-B radiation-induced oxidative stress in human dermal keratinocytes. Pharmazie. 2015 Jun;70(6):381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavinato M., Jansen-Dürr P. Molecular mechanisms of UVB-induced senescence of dermal fibroblasts and its relevance for photoaging of the human skin. Exp Gerontol. 2017 Aug;94:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai B.X., Jin S.L., Luo D., Lin X.F., Gao J. Ginsenoside Rb1 suppresses ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis by inducing DNA repair. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009 May;32(5):837–841. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee K.T., Jung T.W., Lee H.J., Kim S.G., Shin Y.S., Whang W.K. The antidiabetic effect of ginsenoside Rb2 via activation of AMPK. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0719-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujimoto J., Sakaguchi H., Aoki I., Toyoki H., Khatun S., Tamaya T. Inhibitory effect of gin- senoside-Rb2 on invasiveness of uterine endometrial cancer cells to the basement mem- brane. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2001;22:339–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato K., Mochizuki M., Saiki I., Yoo Y.C., Samukawa K., Azuma I. Inhibition of tumor angio- genesis and metastasis by a saponin of Panax ginseng, ginsenoside-Rb2. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994;17:635–639. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo Y.C., Lee J., Park S.R., Nam K.Y., Cho Y.H., Choi J.E. Protective effect of ginsenoside-Rb2 from Korean red ginseng on the lethal infection of haemagglutinating virus of Japan in mice. J Ginseng Res. 2013;37:80–86. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh S.J., Kim K., Lim C.J. Suppressive properties of ginsenoside Rb2, a protopanaxadiol-type ginseng saponin, on reactive oxygen species and matrix metalloproteinase-2 in UV-B-irradiated human dermal keratinocytes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79(7):1075–1081. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1020752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y.H., Park K.H., Rho H.M. Transcriptional activation of the Cu,Zn-superoxide dis- mutase gene through the AP2 site by ginsen- oside Rb2 extracted from a medicinal plant, Panax ginseng. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24539–24543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh S.J., Kim K., Lim C.J. Suppressive properties of ginsenoside Rb2, a protopanaxadiol-type ginseng saponin, on reactive oxygen species and matrix metalloproteinase-2 in UV-B-irradiated human dermal keratinocytes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79(7):1075–1081. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1020752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi S. Epidermis proliferative effect of the Panax ginseng ginsenoside Rb2. Arch Pharm Res. 2002 Feb;25(1):71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02975265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khavkin J., Ellis D.A. Aging skin: histology, physiology, and pathology. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2011 May;19(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harkey M.R., Henderson G.L., Gershwin M.E., Stern J.S., Hackman R.M. Variability in commercial ginseng products: an analysis of 25 preparations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1101–1106. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh Y., Lim H.W., Park K.H., Huang Y.H., Yoon J.Y., Kim K., Lim C.J. Ginsenoside Rc protects against UVB-induced photooxidative damage in epidermal keratinocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2017 Sep;16(3):2907–2914. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim W.K., Song S.Y., Oh W.K., et al. Wound-healing effect of ginsenoside Rd from leaves of Panax ginseng via cyclic AMP- dependent protein kinase pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;702:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Z., Li J.J., Gu L.J., Zhang D.L., Wang Y.B., Sung C.K. Ginsenosides Rb₁ and Rd regulate proliferation of mature keratinocytes through induction of p63 expression in hair follicles. Phytother Res. 2013 Jul;27(7):1095–1101. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ngo H.T.T., Hwang E., Seo S.A., Yang J.E., Nguyen Q.T.N., Do N.Q., Yi T.H. Mixture of enzyme-processed Panax ginseng and Gastrodia elata extract prevents UVB-induced decrease of procollagen type 1 and increase of MMP-1 and IL-6 in human dermal fibroblasts. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2020 Nov;84(11):2327–2336. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2020.1793657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin H.S., Park S.Y., Hwang E.S., Lee D.G., Song H.G., Mavlonov G.T., Yi T.H. The inductive effect of ginsenoside F2 on hair growth by altering the WNT signal pathway in telogen mouse skin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014 May 5;730:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi W.Y., Lim H.W., Lim C.J. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidative and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitory properties of 20(R)-ginsenoside Rh2 in cultured macrophages and keratinocytes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013 Feb;65(2):310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shin H.S., Park S.Y., Hwang E.S., Lee D.G., Mavlonov G.T., Yi T.H. Ginsenoside F2 reduces hair loss by controlling apoptosis through the sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage activating protein and transforming growth factor-β pathways in a dihydrotestosterone-induced mouse model. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37(5):755–763. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park S.H., Seo W., Eun H.S., Kim S.Y., Jo E., Kim M.H., Choi W.M., Lee J.H., Shim Y.R., Cui C.H., et al. Protective effects of ginsenoside F2 on 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced skin inflammation in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016 Sep 30;478(4):1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lim C.J., Choi W.Y., Jung H.J. Stereoselective skin anti-photoaging properties of ginsenoside Rg3 in UV-B-irradiated keratinocytes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37(10):1583–1590. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b14-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jang I.S., Jo E., Park S.J., Baek S.J., Hwang I.H., Kang H.M., Lee J.H., Kwon J., Son J., Kwon H.J., et al. Proteomic analyses reveal that ginsenoside Rg3(S) partially reverses cellular senescence in human dermal fibroblasts by inducing peroxiredoxin. J Ginseng Res. 2020 Jan;44(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhee S.G., Kang S.W., Jeong W., Chang T.S., Wang K.S., Woo H.A. Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee H., Hong Y., Tran Q., Cho H., Kim M., Kim C., Kwon S.H., Park S., Park J., Park J. A new role for the ginsenoside RG3 in antiaging via mitochondria function in ultraviolet-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts. J Ginseng Res. 2019 Jul;43(3):431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tao R., Coleman M.C., Pennington J.D., Ozden O., Park S.H., Jiang H., Kim H.S., Flynn C.R., Hill S., Hayes McDonald W., et al. Sirt3-mediated deacetylation of evolutionarily conserved lysine 122 regulates MnSOD activity in response to stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang K.E., Jang H.J., Hwang I.H., Hong E.M., Lee M.G., Lee S., Jang I.S., Choi J.S. Stereoisomer-specific ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 reverses replicative senescence of human diploid fibroblasts via Akt-mTOR-Sirtuin signaling. J Ginseng Res. 2020 Mar;44(2):341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng L., Sun X., Hu C., Jin R., Sun B., Shi Y., Zhang L., Cui W., Zhang Y. In vivo inhibition of hypertrophic scars by implantable ginsenoside-Rg3-loaded electrospun fibrous membranes. Acta Biomater. 2013 Dec;9(12):9461–9473. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu T., Yang R., Ma X., Chen W., Liu S., Liu X., Cai X., Xu H., Chi B. Bionic poly(γ-glutamic acid) electrospun fibrous scaffolds for preventing hypertrophic scars. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019 Jul;8(13) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao L., Wang L., Chang L., Hou Y., Wei C., Wu Y. Ginsenoside CK-loaded self-nanomicellizing solid dispersion with enhanced solubility and oral bioavailability. Pharm Dev Technol. 2020 Nov;25(9):1127–1138. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2020.1800730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang X.D., Yang Y.Y., Ouyang D.S., Yang G.P. A review of biotransformation and pharmacology of ginsenoside compound K. Fitoterapia. 2015 Jan;100:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim S., Kang B.Y., Cho S.Y., Sung D.S., Chang H.K., Yeom M.H., Kim D.H., Sim Y.C., Lee Y.S. Compound K induces expression of hyaluronan synthase 2 gene in transformed human keratinocytes and increases hyaluronan in hair-less mouse skin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;316(2):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cai B.X., Luo D., Lin X.F., Gao J. Compound K suppresses ultraviolet radiation- induced apoptosis by inducing DNA repair in human keratinocytes. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 2008;31(11):1483–1488. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-2134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.He D., Sun J., Zhu X., Nian S., Liu J. Compound K increases type I procollagen level and decreases matrix metalloproteinase-1 activity and level in ultraviolet-A-irradiated fibroblasts. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011 Mar;110(3):153–160. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(11)60025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shin D.J., Kim J.E., Lim T.G., Jeong E.H., Park G., Kang N.J., Park J.S., Yeom M.H., Oh D.K., Bode A.M., et al. 20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol suppresses UV-Induced MMP-1 expression through AMPK-mediated mTOR inhibition as a downstream of the PKA-LKB1 pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2014 Oct;115(10):1702–1711. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim E., Kim D., Yoo S., Hong Y.H., Han S.Y., Jeong S., Jeong D., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y., Park J. The skin protective effects of compound K, a metabolite of ginsenoside Rb1 from Panax ginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2018 Apr;42(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benhadou F., Mintoff D., Del Marmol V., Psoriasis Keratinocytes or immune cells - which is the trigger? Dermatology. 2019;235(2):1e10. doi: 10.1159/000495291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fan H., Wang Y., Zhang X., Chen J., Zhou Q., Yu Z., Chen Y., Chen Z., Gu J., Shi Y. Ginsenoside compound K ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis through inhibiting REG3A/RegIIIγ expression in keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019 Aug 6;515(4):665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bae E.A., Han M.J., Kim E.J., Kim D.H. Transformation of ginseng saponins to ginsenoside Rh2 by acids and human intestinal bacteria and biological activities of their transformants. Arch Pharm Res. 2004 Jan;27(1):61–67. doi: 10.1007/BF02980048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oh S.J., Lee S., Choi W.Y., Lim C.J. Skin anti-photoaging properties of ginsenoside Rh2 epimers in UV-B-irradiated human keratinocyte cells. J Biosci. 2014 Sep;39(4):673–682. doi: 10.1007/s12038-014-9460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Choi W.Y., Lim H.W., Lim C.J. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidative and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitory properties of 20(R)-ginsenoside Rh2 in cultured macrophages and keratinocytes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013 Feb;65(2):310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou J., Gao Y., Yi X., Ding Y. Ginsenoside Rh2 suppresses neovascularization in xenograft psoriasis model. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(3):980–987. doi: 10.1159/000430272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun M., Zhu C., Long J., Lu C., Pan X., Wu C. PLGA microsphere-based composite hydrogel for dual delivery of ciprofloxacin and ginsenoside Rh2 to treat Staphylococcus aureus-induced skin infections. Drug Deliv. 2020 Dec;27(1):632–641. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2020.1756985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fu B.D., Bi W.Y., He C.L., Zhu W., Shen H.Q., Yi P.F., Wang L., Wang D.C., Wei X.B. Sulfated derivatives of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2 and their inhibitory effects on LPS-induced inflammatory cytokines and mediators. Fitoterapia. 2013 Jan;84:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shin D., Moon H.W., Oh Y., Kim K., Kim D.D., Lim C.J. Defensive properties of ginsenoside Re against UV-B-induced oxidative stress through up-regulating glutathione and superoxide dismutase in HaCaT keratinocytes. Iran J Pharm Res. 2018;17(1):249–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oh Y., Lim H.W., Kim K., Lim C.J. Ginsenoside Re improves skin barrier function in HaCaT keratinocytes under normal growth conditions. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2016 Nov;80(11):2165–2167. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2016.1206808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paul S., Shin H.S., Kang S.C. Inhibition of inflammations and macrophage activation by ginsenoside-Re isolated from Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) Food Chem Toxicol. 2012 May;50(5):1354–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Serrano M., Lin A.W., McCurrach M.E., Beach D., Lowe S.W. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang X.Y., Wang Y.G., Wang Y.F. Ginsenoside Rb1, Rg1 and three extracts of traditional Chinese medicine attenuate ultraviolet B-induced G1 growth arrest in HaCaT cells and dermal fibroblasts involve down-regulating the expression of p16, p21 and p53. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011 Aug;27(4):203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou Y., Wang Y.P., He Y.H., Ding J.C. Ginsenoside Rg1 performs anti-aging functions by suppressing mitochondrial pathway-mediated apoptosis and activating sirtuin 3 (SIRT3)/Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) pathway in sca-1⁺ HSC/HPC cells of an aging rat model. Med Sci Monit. 2020 Apr 7;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.920666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tang Y.L., Zhou Y., Wang Y.P., He Y.H., Ding J.C., Li Y., Wang C.L. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against Sca-1+ HSC/HPC cell aging by regulating the SIRT1-FOXO3 and SIRT3-SOD2 signaling pathways in a γ-ray irradiation-induced aging mice model. Exp Ther Med. 2020 Aug;20(2):1245–1252. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lou J.S., Chen X.E., Zhang Y., Gao Z.W., Chen T.P., Zhang G.Q., Ji C. Photoprotective and immunoregulatory capacity of ginsenoside Rg1 in chronic ultraviolet B-irradiated BALB/c mouse skin. Exp Ther Med. 2013 Oct;6(4):1022–1028. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu M., Zhang J.T. The immunoregulatory effects of ginsenoside Rg1 in aged rats. Acta Pharm Sin. 1995;30:818–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shi Q., He Q., Chen W., Long J., Zhang B. Ginsenoside Rg1 abolish imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in BALB/c mice via downregulating NF-κB signaling pathway. J Food Biochem. 2019 Nov;43(11) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kang H.J., Huang Y.H., Lim H.W., Shin D., Jang K., Lee Y., Kim K., Lim C.J. Stereospecificity of ginsenoside Rg2 epimers in the protective response against UV-B radiation-induced oxidative stress in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2016 Dec;165:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chung Y.H., Jeong S.A., Choi H.S., Ro S., Lee J.S., Park J.K. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg2 and astaxanthin mixture against UVB-induced DNA damage. Anim Cells Syst (Seoul) 2018 Oct 9;22(6):400–406. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2018.1523806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bae E.A., Shin J.E., Kim D.H. Metabolism of ginsenoside Re by human intestinal microflora and its estrogenic effect. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:1903–1908. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim J.H., Baek E.J., Lee E.J., Yeom M.H., Park J.S., Lee K.W., Kang N.J. Ginsenoside F1 attenuates hyperpigmentation in B16F10 melanoma cells by inducing dendrite retraction and activating Rho signalling. Exp Dermatol. 2015 Feb;24(2):150–152. doi: 10.1111/exd.12586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee C.S., Nam G., Bae I.H., Park J. Whitening efficacy of ginsenoside F1 through inhibition of melanin transfer in cocultured human melanocytes-keratinocytes and three-dimensional human skin equivalent. J Ginseng Res. 2019 Apr;43(2):300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Han J., Lee E., Kim E., Yeom M.H., Kwon O., Yoon T.H., Lee T.R., Kim K. Role of epidermal γδ T-cell-derived interleukin 13 in the skin-whitening effect of Ginsenoside F1. Exp Dermatol. 2014 Nov;23(11):860–862. doi: 10.1111/exd.12531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mohnen D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008 Jun;11(3):266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Beran F., Köllner T.G., Gershenzon J., Tholl D. Chemical convergence between plants and insects: biosynthetic origins and functions of common secondary metabolites. New Phytol. 2019 Jul;223(1):52–67. doi: 10.1111/nph.15718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cortinovis C., Caloni F. Alkaloid-containing plants poisonous to cattle and horses in europe. Toxins (Basel) 2015 Dec 8;7(12):5301–5307. doi: 10.3390/toxins7124884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ferrentino G., Morozova K., Horn C., Scampicchio M. Extraction of essential oils from medicinal plants and their utilization as food antioxidants. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(5):519–541. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200121092018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sharmeen J.B., Mahomoodally F.M., Zengin G., Maggi F. Essential oils as natural sources of fragrance compounds for cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. Molecules. 2021 Jan 27;26(3):666. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jesumani V., Du H., Pei P., Aslam M., Huang N. Comparative study on skin protection activity of polyphenol-rich extract and polysaccharide-rich extract from Sargassum vachellianum. PLoS One. 2020 Jan 7;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim N., Estrada O., Chavez B., Stewart C., D'Auria J.C. Tropane and granatane alkaloid biosynthesis: a systematic analysis. Molecules. 2016 Nov 11;21(11):1510. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Amato D.V., Amato D.N., Blancett L.T., Mavrodi O.V., Martin W.B., Swilley S.N., Sandoz M.J., Shearer G., Mavrodi D.V., Patton D.L. A bio-based pro-antimicrobial polymer network via degradable acetal linkages. Acta Biomater. 2018 Feb;67:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Meng H., Liu X.K., Li J.R., Bao T.Y., Yi F. Bibliometric analysis of the effects of ginseng on skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jan;21(1):99–107. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jiang F., Zhou C., Li Y., Deng H., Gong T., Chen J., Chen T., Yang J., Zhu P. Metabolic engineering of yeasts for green and sustainable production of bioactive ginsenosides F2 and 3β,20S-Di-O-Glc-DM. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022 Jul;12(7):3167–3176. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.You L., Cha S., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. Ginsenosides are active ingredients in Panax ginseng with immunomodulatory properties from cellular to organismal levels. J Ginseng Res. 2022 Nov;46(6):711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee T.X.Y., Wu J., Jean W.H., Condello G., Alkhatib A., Hsieh C.C., Hsieh Y.W., Huang C.Y., Kuo C.H. Reduced stem cell aging in exercised human skeletal muscle is enhanced by ginsenoside Rg1. Aging (Albany NY) 2021 Jun 28;13(12):16567–16576. doi: 10.18632/aging.203176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chuang T.H., Kim J.H., Seol S.Y., Kim Y.J., Lee Y.J. The effects of Korean red ginseng on biological aging and antioxidant capacity in postmenopausal women: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Nutrients. 2021 Sep 2;13(9):3090. doi: 10.3390/nu13093090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jung S.J., Oh M.R., Lee D.Y., Lee Y.S., Kim G.S., Park S.H., Han S.K., Kim Y.O., Yoon S.J., Chae S.W. Effect of ginseng extracts on the improvement of osteopathic and arthritis symptoms in women with osteopenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. 2021 Sep 24;13(10):3352. doi: 10.3390/nu13103352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mukherjee P.K., Maity N., Nema N.K., Sarkar B.K. Bioactive compounds from natural resources against skin aging. Phytomedicine. 2011 Dec 15;19(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang H.E., Chu M.Y., Jiang T., Song X.H., Hou J.F., Cheng L.Y., Feng Y., Chen C.B., Wang E.P. By-product of the red ginseng manufacturing process as potential material for use as cosmetics: chemical profiling and in vitro antioxidant and whitening activities. Molecules. 2022 Nov 24;27(23):8202. doi: 10.3390/molecules27238202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meng H., Liu X.K., Li J.R., Bao T.Y., Yi F. Bibliometric analysis of the effects of ginseng on skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jan;21(1):99–107. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]