Abstract

Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi strains belonging to eight different outbreaks of typhoid fever that occurred in Spain between 1989 and 1994 were analyzed by ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. For three outbreaks, two different patterns were detected for each outbreak. The partial digestion analysis by the intron-encoded endonuclease I-CeuI of the two different strains from each outbreak provided an excellent tool for examining the organization of the genomes of epidemiologically related strains. S. enterica serotype Typhi seems to be more susceptible than other serotypes to genetic rearrangements produced by homologous recombinations between rrn operons; these rearrangements do not substantially alter the stability or survival of the bacterium. We conclude that genetic rearrangements can occur during the emergence of an outbreak.

Typhoid fever is an important public health problem only in developing countries. However, outbreaks have also occurred in industrialized countries, perhaps due to the high frequency with which patients suffering from typhoid fever convert into (asymptomatic) carriers, a state in which they can continue up to several years.

Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi, the causal agent of typhoid fever, is the most homogeneous of the S. enterica serotypes. On the basis of their phylogenetic origin, the strains of this serotype seem to originate from a single clone, according to Reeves et al. (10), or from two clones, according to Selander et al. (11). On the other hand, some methods used in epidemiological studies, such as determination of phage type (15), which is the phenotypic marker of choice for this serotype, or the more modern genotypic methods like ribotyping (1), IS200 insertion fragment distribution analysis (14), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (9), have demonstrated a high discrimination index within this serotype. In these studies, the comparison of the obtained restriction patterns, with or without hybridization with specific probes, determines the epidemiological relationship among different isolates.

Ideally, the patterns obtained from strains which belong to the same outbreak should be indistinguishable. However, variations among these strains that may represent genetic events that occurred during the emergence of the outbreak and which make it difficult to establish the relationship between these strains have been described frequently (2). The criteria proposed by Tenover et al. (13) can serve as a good guide for the interpretation of the restriction patterns obtained by PFGE for epidemiologically related strains and the determination of the category of their genetic relationship.

In enteric bacteria, chromosomal rearrangements such as duplications and deletions may appear quite frequently; inversions seldom occur, except for those between the rrn operons, which can be quite common (4). In spite of this, the overall chromosomal organization has been highly conserved during evolution, which suggests a strong negative selection of the mutant cells (6).

The serotype Typhi of S. enterica seems to represent an exception to this high conservation of the genetic structure. Liu and Sanderson (8) studied the distribution of the rrn interoperon fragments in the chromosomes of 127 strains of this serotype by subjecting the fragments obtained by digestion with I-CeuI to PFGE. This restriction enzyme cuts exclusively in the rrn gene of the 23S rRNA fraction. Liu and Sanderson showed that the I-CeuI fragments could be rearranged into 21 different orders.

In the present study, we assessed whether the detected variations among strains of some outbreaks may be caused by such reorganizations. Therefore, we analyzed the ribotypes and the PFGE types of 85 selected S. enterica serotype Typhi strains. These strains belonged to eight different outbreaks of typhoid fever that occurred in Spain between 1989 and 1994 (5, 9, 16, 17) and were already characterized by phage typing in accordance with the method of Guinée and van Neuween (3). The related strains were epidemiologically well described as members of an outbreak set and belonged to the same phage type (2) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of the types obtained by analysis of the studied outbreaks using conventional and molecular typing methods

| Outbreak no. | Yr of isolation | No. of strains | Phage type(s) | Ribotype

|

PFGE type using XbaI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HindIII | PstI | ClaI | |||||

| 1 | 1989 | 4 | C1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1990 | 5 | C4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | C4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 1990 | 4 | E1a | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 1991 | 14 | 34 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | 34 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | ||

| 5 | 1989–94 | 25 | 46 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| 12 | 46 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 7 | ||

| 6 | 1992 | 4 | Ade | 9 | 7 | 9 | 8 |

| 7 | 1991–94 | 5 | D1 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 8 | 1994 | 9 | I + IV | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

The ribotyping of the DNA digested by HindIII, EcoRI, and PstI and then subjected to electrophoresis for 18 h at 40 V was carried out as described by Altwegg et al. (1).

The PFGE analysis of the DNA restriction fragments obtained by digestion using XbaI was executed as described by Smith et al. (12). Electrophoresis was carried out in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer with a Chef DRII machine (Bio-Rad). The conditions were 200 V for 16 h at 12°C with a ramp time of 1 to 50 s.

Analysis of the I-CeuI restriction fragments was carried out as described by Liu and Sanderson (8), using the Chef DRII machine, for strains of each outbreak in which we detected two different patterns. Electrophoresis was carried out over 28 h at 200 V and 12°C in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The ramp times were 1 to 40 s for the first 10 h and then 40 to 150 s for the following 18 h. The partial digestions were carried out by reducing the enzyme concentration and the digestion time. The fragments were subjected to electrophoresis at 150 V in two steps: ramp times of 10 to 120 s over 20 h and of 70 to 120 s over 26 h. All enzymes were provided by Boehringer Mannheim, except for I-CeuI, which was purchased at New England Biolabs.

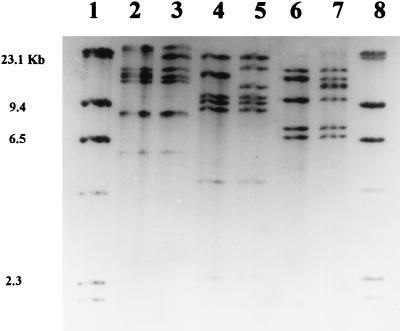

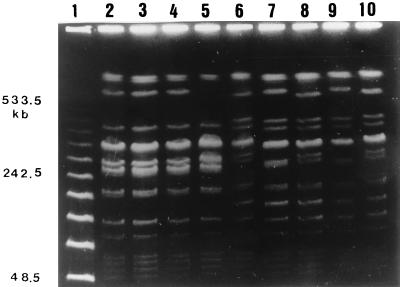

For five of the eight outbreaks studied, the related strains were indistinguishable when the following techniques were used: ribotyping with HindIII, EcoRI, and PstI and PFGE using XbaI. For the other three outbreaks (outbreaks 2, 4, and 5), two different ribotyping patterns for each outbreak were detected (Fig. 1). However, only two of the outbreaks also presented two PFGE patterns (outbreaks 2 and 5) (Fig. 2). The strain distribution for each type was the same when either technique was used (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Restriction fragments of the S. enterica serotype Typhi types from outbreak 2 after hybridization with a digoxigenin-linked marker obtained by using Escherichia coli 16S RNA. Lanes: 2 and 3, ribotypes 2 and 3 obtained by cleavage using HindIII; 4 and 5, ribotypes 2 and 3 obtained by using PstI; 6 and 7, ribotypes 2 and 3 obtained by using ClaI; 1 and 8, molecular size markers, λ phage digested by HindIII.

FIG. 2.

PFGE of the digestion patterns obtained by using XbaI for the two types of S. enterica serotype Typhi from outbreaks 2 (lanes 2 to 5) and 5 (lanes 6 to 10). Lanes: 1, molecular size markers, λ phage concatemers; 2 to 4, PFGE type 2; 5, PFGE type 3; 6, 8, and 10, PFGE type 6; 7 and 9, PFGE type 7.

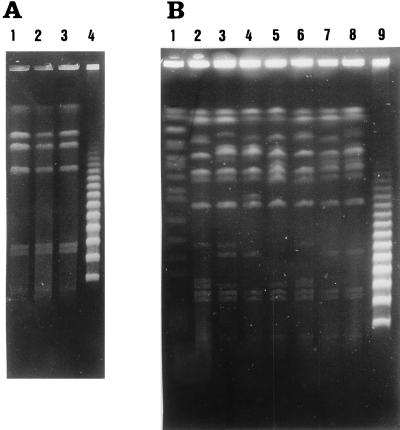

PFGE of the fragments produced by complete digestion with I-CeuI of the strains of outbreaks 2, 4, and 5 produced identical patterns of seven bands with molecular weights similar to those described for the rrn interoperon fragments of S. enterica serotype Typhi. According to Liu and Sanderson (8), this should indicate that neither inversions nor transpositions have occurred in other zones of the chromosome, which would have produced different I-CeuI fragments, nor have deletions or duplications in which the rrn operons were involved, which would have caused the loss of some of the I-CeuI fragments or doubled the intensity of some of the bands (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

(A) PFGE pattern after complete digestion of the S. enterica serotype Typhi strains using I-CeuI (lanes 1 to 3). Lane 4 contains molecular size markers, λ phage concatemers. (B) PFGE patterns after partial digestion of the S. enterica serotype Typhi strains using I-CeuI. Lanes: 1, molecular size markers, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; 2, strain not related to any of the studied outbreaks; 3 and 4, strains of outbreak 2, ribotypes 2 and 3; 5 and 6, strains of outbreak 4, ribotypes 5 and 6; 7 and 8, strains of outbreak 5, ribotypes 7 and 8; 9, molecular size markers, λ phage concatemers.

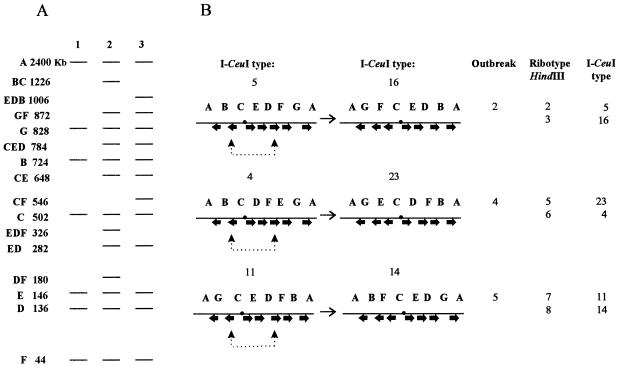

The analysis of the fragments obtained by partial digestion of the same strains using I-CeuI revealed different patterns for each type from the same outbreak (Fig. 3). Even if the number and the nature of the implicated genetic recombinations which have given rise to the important variability in the known ribotypes are not known, it may be possible that the reorganization between the two patterns of the same outbreak was caused by the inversion between operons pointing in opposite directions (4). The orders of the I-CeuI fragments in the patterns of one single outbreak as deduced from the partial digestions and the homologous recombinations between the rrn operons postulated for each outbreak are presented in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

(A) I-CeuI restriction fragment size scheme. Lanes: 1, fragments after complete digestion with I-CeuI; 2 and 3, two type fragments from outbreak 2 after partial digestion with I-CeuI. (B) Order of the I-CeuI restriction fragments of the two types of S. enterica serotype Typhi from each of the studied outbreaks. Dotted lines show rrn operons implicated in inversions. I-CeuI types are named in accordance with the nomenclature of Liu and Sanderson (8).

These chromosomal rearrangements can explain the two different patterns found for each of the three studied outbreaks. Consequently, the environments of the two involved rrn operons and presumably also the positions of the recognition sequences of the restriction enzymes in these environments would be modified, which would explain the differences in the two bands detected in the two different ribotypes for the same outbreak. Furthermore, it would be easy to understand the appearance of two PFGE types in the very same strains.

In conclusion, S. enterica serotype Typhi seems to be more susceptible than other serotypes to genetic reorganizations that do not substantially alter the stability and survival of the bacterium (7). These reorganizations, produced by homologous recombinations between rrn operons, could be responsible for the high discrimination index detected in this serotype when molecular methods such as ribotyping and PFGE are used. The frequency with which these events take place in nature is not known, but it may be possible that they occur even during the emergence of an outbreak. This may be supported by the fact that these outbreaks of typhoid fever can be very long lasting, given that humans are the only reservoir of S. enterica serotype Typhi and that the bacteria in carriers can stay active for many years.

For the time in which the outbreaks described in this work were studied, three outbreaks were considered mixed outbreaks, since two different patterns among the strains were identified. The results obtained in this study together with the facts that (i) the related strains belonged to phage types occurring infrequently in Spain (2), (ii) the PFGE types had high homology to each other, and (iii) both patterns were detected in the isolates from one patient and from the index case of outbreak 5 (2, 9) and in the isolates from one patient of outbreak 2 (2, 16) suggest that in each of these outbreaks one pattern may be derived from the other.

Finally, the strains of each outbreak, which are epidemiologically related, can now be considered genetically related if analyzed by PFGE and, on the basis of the criteria of Tenover et al. (13), can be labelled as closely related strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank the epidemiologists and microbiologists from the different Spanish Health Laboratories who submitted all of the data and isolates investigated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altwegg M, Hickman-Brenner F W, Farmer J J., III Ribosomal RNA gene restriction patterns provide increased sensitivity for typing Salmonella typhi strains. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:145–149. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Echeita M A. Clonalidad de Salmonella, serotipo Typhi. Epidemiología molecular. Ph.D. thesis. Madrid, Spain: Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guinnée P A M, van Neuween W J. Phagetyping of Salmonella. Methods Microbiol. 1978;11:157–191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill C W, Harnish B W. Inversions between ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7069–7072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibarluzea J, Dorronsoro R, Larrañaga M, Martinez E. Brote de fiebre tifoidea asociado a problema en la red de distribución de agua de consumo. In: Ibarluzea J, Larrañaga M, editors. Serie de documentos de salud pública. Vol. 8. Vitoria, Spain: Servicio Vasco de Salud; 1990. pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krawiec S, Riley M. Organization of the bacterial chromosome. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:502–539. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.502-539.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu S-L, Sanderson K E. Rearrangements in the genome of the bacterium Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1018–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S-L, Sanderson K E. Highly plastic chromosomal organization in Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10303–10308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarro F, Llovet T, Echeita M A, Coll P, Aladueña A, Usera M A, Prats G. Molecular typing of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2831–2834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2831-2834.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves M W, Evins G M, Heiba A A, Plikaytis B D, Farmer J J., III Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:313–320. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.313-320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selander R K, Beltran P, Smith N H, Helmuth R, Rubin F A, Kopecko D J, Ferris K, Tall B D, Cravioto A, Musser J M. Evolutionary genetic relationships of clones of Salmonella serovars that cause human typhoid and other enteric fevers. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2262–2275. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2262-2275.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith C L, Klco S R, Cantor C R. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and the technology of large DNA molecules. In: Davies K, editor. Genome analysis: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1988. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Threlfall E J, Torre E, Ward L R, Dávalos-Pérez A, Rowe B, Gibert I. Insertion sequence IS200 fingerprinting of Salmonella typhi: an assessment of epidemiological applicability. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:253–261. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usera M A. Salmonella typhi in Spain: epidemiological markers and antimicrobial susceptibility (1979–1981) In: Cabello F, Hormaeche C, Mastroeni P, Bonina L, editors. Biology of Salmonella. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usera M A, Aladueña A, Echeita M A, Amor E, Gomez-Garcés J L, Ibañez C, Mendez Y, Sanz J C, Lopez-Brea M. Investigation of an outbreak of Salmonella Typhi in a public school in Madrid. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9:251–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00146259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xercavins M, Llovet T, Navarro F, Morera M A, Moré J, Bella F, Freixas N, Simó M, Eheita A, Coll P, Garau J, Prats G. Epidemiology of an unusually prolonged outbreak of typhoid fever in Terrassa, Spain. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:506–510. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]