Abstract

Introduction

Treatment persistence is a proxy for efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction, and a switch in treatment or treatment discontinuation has been associated with increased indirect and direct costs in inflammatory arthritis (IA). Hence, there are both clinical and economic incentives for the identification of factors associated with treatment persistence. Until now, studies have mainly leveraged traditional regression analysis, but it has been suggested that novel approaches, such as statistical learning techniques, may improve our understanding of factors related to treatment persistence. Therefore, we set up a study using nationwide Swedish high-coverage administrative register data with the objective to identify patient groups with distinct persistence of subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (SC-TNFi) treatment in IA, using recursive partitioning, a statistical learning algorithm.

Methods

IA was defined as a diagnosis of rheumatic arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis (AS/uSpA) or psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Adult swedish biologic-naïve patients with IA initiating biologic treatment with a SC-TNFi (adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab or golimumab) between May 6, 2010, and December 31, 2017. Treatment persistence of SC-TNFi was derived based on prescription data and a defined standard daily dose. Patient characteristics, including age, sex, number of health care contacts, comorbidities and treatment, were collected at treatment initiation and 12 months before treatment initiation. Based on these characteristics, we used recursive partitioning in a conditional inference framework to identify patient groups with distinct SC-TNFi treatment persistence by IA diagnosis.

Results

A total of 13,913 patients were included. Approximately 50% had RA, while 27% and 23% had AS/uSpA and PsA, respectively. The recursive partitioning algorithm identified sex and treatment as factors associated with SC-TNFi treatment persistence in PsA and AS/uSpA. Time on treatment in the groups with the lowest treatment persistence was similar across all three indications (9.5–11.3 months), whereas there was more variation in time on treatment across the groups with the highest treatment persistence (18.4–48.9 months).

Conclusions

Women have low SC-TNFi treatment persistence in PsA and AS/uSpA whereas male sex and golimumab are associated with high treatment persistence in these indications. The factors associated with treatment persistence in RA were less distinct but may comprise disease activity and concurrent conventional systemic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02600-3.

Keywords: Biologics, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, Treatment persistence, Recursive partitioning, Rheumatoid arthritis, Psoriatic arthritis, Ankylosing spondylitis, Spondyloarthritis

Key Summary Points

| Treatment persistence is a proxy for effective treatment. Furthermore, high persistence has been associated with reduced direct and indirect costs in inflammatory arthritis. Therefore, identifying factors associated with treatment persistence to subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (SC-TNFi) treatment in inflammatory arthritis could be beneficial from both patient and payer perspectives. |

| It has been suggested that novel approaches, such as statistical learning techniques, may improve our understanding of factors related to treatment persistence. |

| Leveraging Swedish administrative register data, this study aimed to identify patient groups with distinct treatment persistence of SC-TNFis in inflammatory arthritis using recursive partitioning, a statistical learning algorithm. |

| The results show that sex and specific SC-TNFi agent are associated with SC-TNFi treatment persistence in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, factors associated with SC-TNFi treatment persistence were less distinct but may comprise disease activity and concurrent use of conventional systemic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis (AS/uSpA) are among the most common arthritides, and these entities have previously been jointly categorized as inflammatory arthritis (IA). Inflammatory arthritis is characterized in part by the presence of chronic inflammation as indicated by pathologically elevated levels of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα). Common symptoms include pain, swelling and stiffness of peripheral and axial joints [1, 2]. All three diseases may be progressive and result in joint destruction [3–5]. In Sweden, RA is reported to be the most common form of IA, with the 2011 prevalence estimated at 0.77% [6]. The corresponding prevalence for PsA and AS/uSpA has been estimated at 0.25% and 0.18%, respectively [7–9].

Treatment options for IA include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and corticosteroids [10, 11]. Biologics, a subset of DMARDs, constitute a growing group of genetically engineered drugs that modify immune response and include TNF-α inhibitors (TNFi) [12]. TNFi treatments available in Europe can be further subdivided into those administered intravenously, i.e., infliximab, or those administered subcutaneously (SC-TNFi), i.e., adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept and golimumab.

While new effective treatment options have brought the disease under control in many patients with IA during recent decades, a significant proportion nonetheless fail to respond, lose response or experience adverse events while being treated with biologics, necessitating treatment switch or discontinuation [13, 14]. Therefore, in chronic symptomatic diseases such as IA, treatment persistence is a proxy for efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction [15–17]. Furthermore, among patients with IA, treatment discontinuation with SC-TNFi treatment has been associated with increased direct and indirect costs [18–20]. Hence, it is of clinical and economic interest to identify factors that are associated with treatment persistence.

Factors associated with persistence in treatment with biologics in IA have been explored in numerous studies and include age, sex, disease severity, treatment history and treatment type [21, 22]. However, practically all studies have implemented traditional regression analyses when attempting to identify factors associated with treatment persistence. Indeed, two systematic reviews on treatment persistence in IA [21, 22] conclude that novel approaches, such as statistical learning techniques, may improve our understanding of factors related to treatment persistence. Therefore, we set up a study using nationwide Swedish high-quality register data with the objective to identify patient groups with distinct SC-TNFi treatment persistence in IA using recursive partitioning, a statistical learning algorithm.

Methods

Study Setting and Permits

This registry linkage study was conducted in Sweden. The Swedish health care system provides automatic and universal coverage to all legal residents, and co-payment is limited [23]. Therefore, associations between exposures and outcomes are practically unaffected by affordability issues. Furthermore, in Sweden, it is possible to deterministically link administrative registers using personal identifiers unique to each Swedish resident [24].

The national registers included in this study are held by The National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW). Data from the different registries were linked and anonymized by the NBHW prior to data extraction. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (approval number 2019-02774). The reporting of this paper follows the STROBE statement [25].

Data Sources

The data for this study were obtained from three nationwide Swedish administrative registers with practically complete coverage, frequently used for medical research [26–28]. The Prescribed Drug Register (PDR) contains data on all prescriptions dispensed in pharmacies, including anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) codes, date of dispensation and the specialty of the prescriber. The quality of the PDR is high, with the loss of patient information estimated to be < 0.3% [27]. The National Patient Register (NPR) is a population-based register on all inpatient and specialized outpatient care in Sweden. All healthcare providers are mandated by law to report in- and outpatient episodes to the NPR (including dates and diagnoses). It has been estimated that > 99% of all somatic and psychiatric discharges in Sweden are registered in the NPR [26]. The Causes of Death Register contains information on all deaths in Sweden and their underlying causes. Less than two percent of deaths have a missing cause of death [28].

Patients

After the application of a wash-out period (no prescriptions filled for biologics between July 1, 2005, and May 5, 2010), we identified adult patients (≥ 18 years) with RA, PSA or AS/uSpA who filled their first prescription for a SC-TNFi from May 6, 2010, to December 31, 2017. The PDR does not contain information on the indication for a prescription. Therefore, indication for a prescription was determined using an algorithm based on previously described ICD-10 diagnoses [29–31]. After identification, patients were excluded if they met one of five different criteria: (1) if they were < 18 years old at treatment initiation; (2) if they had records of a TNFi administered in an in- or outpatient hospital setting before the date of treatment initiation; (3) if they had < 12 months of both baseline and follow-up periods due to data availability, emigration or death; (4) if they had a filled prescription of SC-TNFi from any department besides rheumatology, orthopedics or rehabilitation departments; (5) if they had no diagnosis record for IA as defined in this study (i.e., AS/uSpA [ICD10: M08.1, M45, M46.1, M46.8 and M46.9], PsA [ICD-10: L40.5, M07.0, M07.1, M07.2 and M07.3] or RA [ICD10: M05.8, M05.9, M06.0 M06.9 and M12.3]). If several IA diagnoses were present, the diagnosis recorded closest in time to the first SC-TNFi prescription was used for patient classification. The rationale for the second exclusion criterion was twofold. First, it was implemented to minimize the risk of deriving incorrect estimates of treatment duration because of ambiguous gaps in the PDR data. Second, this criterion ensured that included patients were biologics-naïve given the exclusion of patients who received biologics via intravenous in a hospital setting.

Outcome

The outcome of the study was treatment persistence. Consistent with methodologic guidance [32] and previous studies [29–31], we defined treatment persistence as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of treatment. The index date was set at treatment initiation and occurred when patients filled their first prescription of adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept or golimumab. Discontinuation was defined to occur at the first of three events: (1) when the last prescription was depleted with no further prescription filled, (2) when the patient had a treatment gap exceeding 60 days between filled prescriptions and (3) when the patient filled a prescription of another biologic or targeted synthetic immunomodulatory treatment (a second SC-TNFi, anakinra, ustekinumab, secukinumab, tocilizumab, rituximab, abatacept, baricitinib or tofacitinib). The duration of individual prescriptions was derived based on a standard defined daily dose and pack size. Accumulated medication from overlapping prescriptions was used to offset any prospective gaps between filled prescriptions to account for the Swedish Pharmacy system, which allows for prescription refills when two-thirds of the previous prescription has been consumed.

Predictors

The exposures of interest in this study were variables potentially associated with treatment persistence [21, 22] and comprised: specific SC-TNFis, age, sex, number of health care contacts, comorbidities, use of steroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and conventional systemic DMARDs (csDMARDs) as well as the highest level of education. (Table 1). Health care contacts were further broken down by setting (inpatient vs. specialized outpatient care) and association to IA based on ICD-10 code. Comorbidities were operationalized as the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] excluding the RA component [33, 34]. All analyses were performed separately for RA, PSA and AS/uSpA.

Table 1.

Potential predictors of drug survival included in the recursive partitioning analysis

| Predictors | Variable type | Categories | ATC/ICD codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Categorical | Male, female | |

| Age at index date | Ratio | NA | |

| SC-TNFi treamtent | Categorical | ETA, ADA, CZP, GLM | L04AB01, L04AB04, L04AB05, L04AB06 |

| Specialized outpatient visits | Ratio | NA | |

| Specialized outpatient visits for IA | Ratio | RA, PsA, AS/uSPA | RA: M05.8, M05.9, M06.0 M06.9 and M12.3, PsA: L40.5, M07.0, M07.1, M07.2 and M07.3, AS/uSpA: M08.1, M45, M46.1, M46.8 and M46.9 |

| Inpatient stays | Ratio | NA | |

| Inpatient stays Hospitalizations for IA | Ratio | RA, PsA, AS/uSPA | |

| RA and age-adjusted CCIa | Ordinal | NA | NAa |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Categorical | Yes/no | H02AA, H02AB, H02BX |

| Oral NSAIDs | Categorical | Yes/no | M01A, N02BA01, N02BA06, N02BA11 |

| csDMARDs | Categorical | Yes/no | L04AX03, L01BA01, M01CX01, P01BA02, A07EC01, M01CX02, L04AA13, L04AX01, L04AA01, L04AD01, S01XA18, M01CB, A01AB23M, J01AA08, M01CC01 |

All variables were measured during 1 year before index date except SC-TNFI treatment that was extracted at the index date and sex, which was invariant. SC-TNFi subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, RA rheumatoid arthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis, AS/uSpA ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis, IA inflammatory arthritis, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, csDMARDs conventional systemic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, NA non-applicable, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, ATC The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical, ADA adalimumab, CZP certolizumab pegol, ETA etanercept, GLM golimumab. aThe CCI was age adjusted and RA component removed

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics were presented using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables depending on the approximate normality of the underlying distributions. For the CCI and inpatient care resource use, both mean and standard deviation and median and interquartile range were presented reflecting the mass of observations at zero. Categorical variables were presented using frequencies and percentages.

We used recursive partitioning in a conditional inference framework [35] to identify patient groups with distinct treatment persistence by IA diagnosis. Recursive partitioning is a statistical learning technique that classifies subjects according to their observed outcomes. It is arguably more intuitive and provides more clinically interpretable results than traditional regression analysis [36]. The reason is that the output of the analysis comprises patient groups defined by specific characteristics instead of a coefficient describing the change in the outcome for a one-unit change in a predictor controlled for covariates. Other benefits include that recursive partitioning allows for inclusion of an unlimited number of predictors, is adept at finding non-linear relationships and does not assume that ordinal variables are interval or ratio scales in nature [35].

The recursive partitioning algorithm identifies subgroups with differences in outcomes using sequential splits that each maximize the difference in outcomes between groups. The partitioning (“splitting”) process in this study used a conditional inference framework and comprised two steps: The first step consisted of testing the global null-hypothesis of independence between all included predictors and the outcomes. If the null hypothesis of independence was rejected, a second step was initiated where the algorithm identified the predictor with the strongest association to the outcome, and the data were split on this variable. Splits were always in two, and for continuous and categorical variables the algorithm identified optimal cut-offs (i.e., the cut-off that maximized the difference in outcomes between the two groups). The process is recursive in the sense that the splitting process is repeated until the null hypothesis of independence in the first step cannot be rejected, and then the algorithm stops. An α of 0.05 was used for this analysis, and the p values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction [37, 38]. Finally, we compared the treatment persistence in the identified groups and combined groups for which treatment persistence was not statistically different from each other (p > 0.05).

To explore differences in the results between recursive partitioning and traditional regression analysis, we fitted bivariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards (PH) models with treatment persistence and the potential predictors as covariates. We ran both bivariable analysis (one predictor per model) and multivariable analyses (all predictors in the same model) for each of the three indications. In the Cox PH models, we assumed that predictors with a p value < 0.05 were statistically significant and therefore qualified as predictors.

The analysis was performed in R version 3.54.2. Recursive partitioning was implemented using ctree from the partykit package [35]. Differences in drug survival between different identified groups were tested using log-rank tests starting with the two groups with the lowest treatment persistence.

Results

Patients and Baseline Characteristics

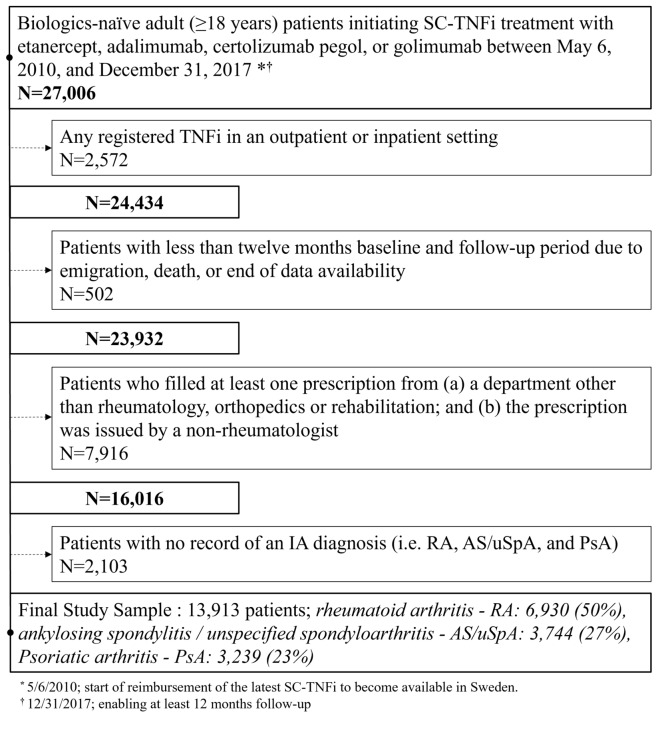

The overall study population included 13,913 patients (Fig. 1). Approximately 50% of the patients had RA and a quarter of patients had PsA and AS/uSpA, respectively (Table 2). Patients with RA were predominately women (76%) whereas the sex distribution in AS/uSpA (47 women) and PsA (54% women) was more even. In the year prior to index date, most patients had taken NSAIDs whereas the use of csDMARDs and systemic steroids varied more across indications.

Fig. 1.

Sequential sample selection flow chart. SC-TNFi subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. IA inflammatory arthritis

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics as measured one year before index date

| PsA | AS/uSpA | RA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3239 | N = 3744 | N = 6930 | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 49.25 (12.8) | 41.76 (13.4) | 54.97 (14.3) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 50.0 (40–58) | 41.0 (31–51) | 57.0 (45–66) |

| Female—n (%) | 1737 (53.6) | 1742 (46.5) | 5246 (75.7) |

| Index year—n (%) | |||

| Indexed 2010 | 176 (5.4) | 218 (5.8) | 605 (8.7) |

| Indexed 2011 | 327 (10.1) | 372 (9.9) | 896 (12.9) |

| Indexed 2012 | 353 (10.9) | 354 (9.5) | 775 (11.2) |

| Indexed 2013 | 415 (12.8) | 495 (13.2) | 839 (12.1) |

| Indexed 2014 | 447 (13.8) | 505 (13.5) | 860 (12.4) |

| Indexed 2015 | 472 (14.6) | 595 (15.9) | 952 (13.7) |

| Indexed 2016 | 473 (14.6) | 593 (15.8) | 990 (14.3) |

| Indexed 2017 | 576 (17.8) | 612 (16.3) | 1013 (14.6) |

| Age and RA-adjusted CCIa | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.51 (1.2) | 0.94 (1.2) | 2.07 (1.4) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 1.0 (1–2) | 1.0 (0–2) | 2.0 (1–3) |

| Co-medication | |||

| NSAIDs—n (%) | 2362 (72.9) | 3089 (82.5) | 4397 (63.4) |

| csDMARDsb—n (%) | 2590 (80.0) | 1564 (41.8) | 6322 (91.2) |

| Methotrexateb—n (%) | 2182 (67.4) | 854 (22.8) | 5497 (79.3) |

| Steroids—n (%) | 1572 (48.5) | 1417 (37.8) | 5068 (73.1) |

| Total outpatient visits | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.52 (5.1) | 6.47 (5.1) | 6.74 (5.0) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 5.0 (3–8) | 5.0 (3–8) | 6.0 (3–9) |

| IA-related outpatient visits | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.46 (2.6) | 2.97 (2.6) | 3.82 (2.9) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 3.0 (2–5) | 2.0 (1–4) | 3.0 (2–5) |

| Total inpatient visits | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.20 (0.7) | 0.25 (0.8) | 0.28 (0.8) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) |

| IA-related inpatient visits | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.02 (0.2) | 0.04 (0.3) | 0.06 (0.3) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) |

All variables were measured during 1 year before index except SC-TNFI treatment that was extracted at index and sex, which was invariant. SC-TNFi subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, RA rheumatoid arthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis, AS/uSpA ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis, IA inflammatory arthritis, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, csDMARDs conventional systemic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

aThe CCI was age adjusted and the RA component removed

bMethotrexate is included in csDMARDs use. Methotrexate use is presented as a perfect subset of the csDMARDs category, and consequently denominators are the same

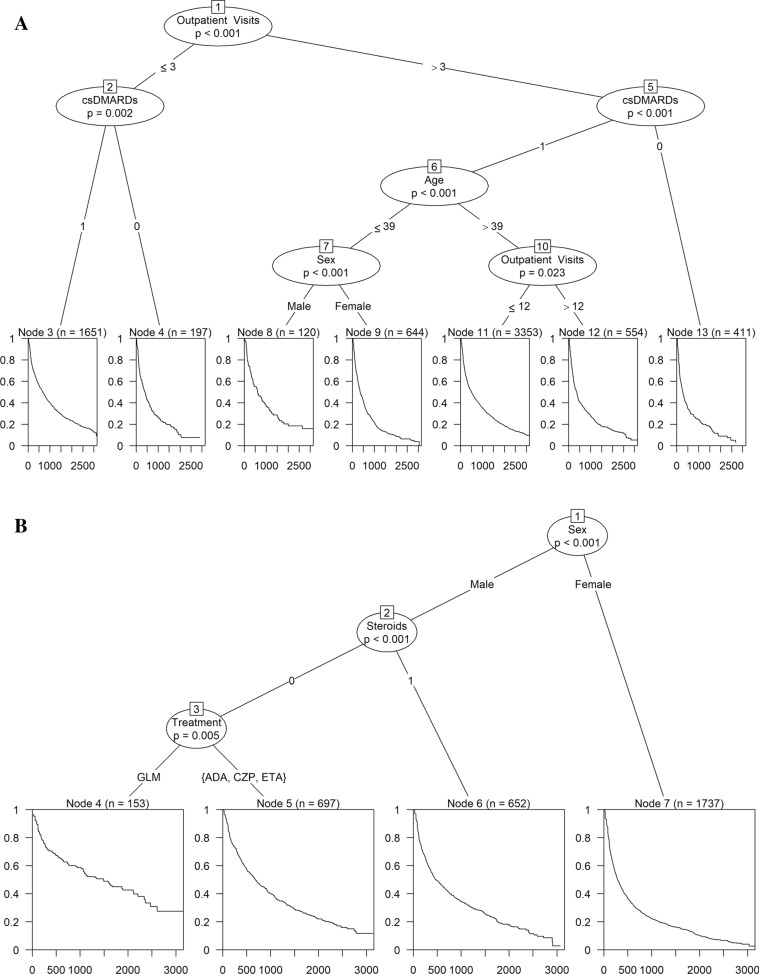

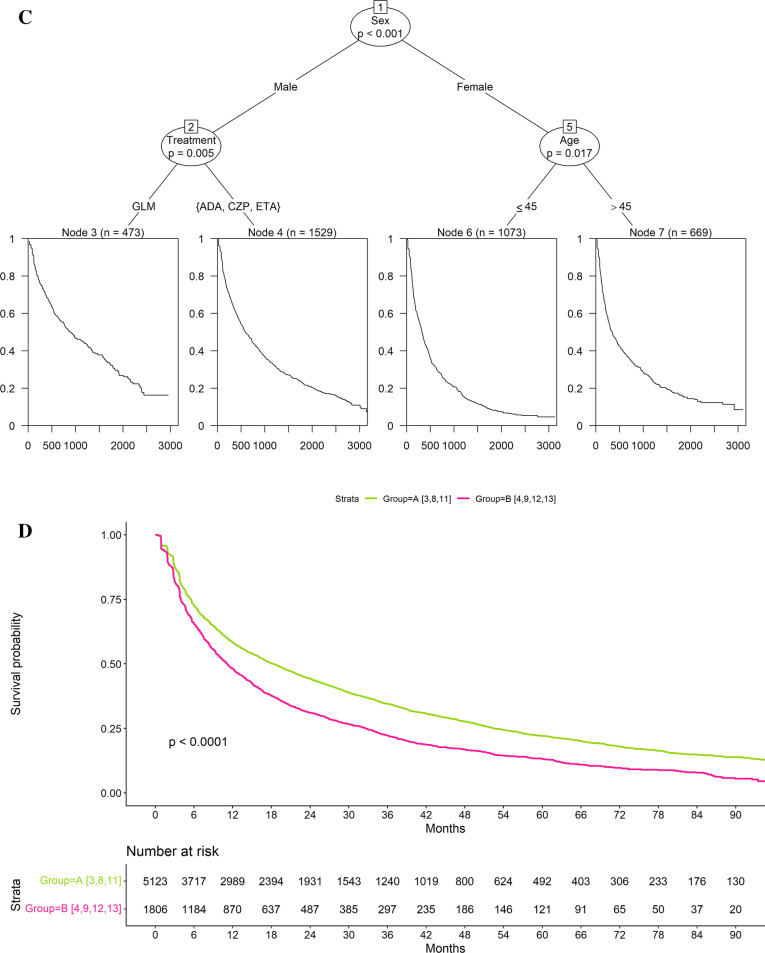

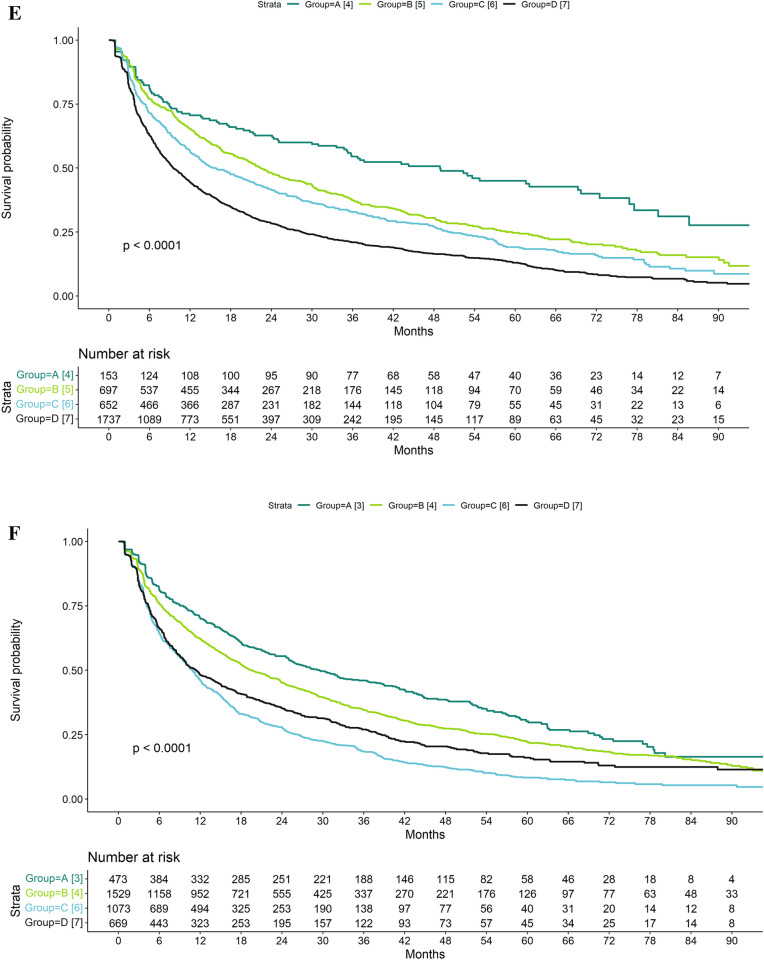

Groups with Distinct Treatment Persistence

The recursive partitioning identified two groups with distinct treatment persistence in RA, four in PsA and four in AS/uSpA (Fig. 2, Table 3). In RA, the two groups were combinations of three and four separate subgroups with similar treatment persistence, respectively (Fig. 2, Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Decision tree derived using recursive partitioning (A rheumatoid arthritis [RA]; B psoriatic arthritis [PsA]; C ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis [AS/uSpA]) and drug survival for identified groups (D RA; E PsA; F AS/uSpA) in patients treated with subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors (SC-TNFis). csDMARDs conventional systemic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, ADA adalimumab, CZP certolizumab pegol, ETA etanercept, GLM golimumab

Table 3.

Groups with distinct drug survival from the recursive partitioning analysis after combining subgroups with similar drug survival in each indication

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | |||||||

| Nodes from treea and group characteristics |

3: Patients with few outpatient visits (≤ 3) and on csDMARDs 8: Patients with > 3 outpatient visits, on csDMARDs, age ≤ 39 and who were male 11: Patients with 3–12 outpatient visits, on csDMARDs and age > 39 |

4: Patients with few outpatient visits (≤ 3) and on csDMARDs 9: Patients with > 3 outpatient visits, on csDMARDs, age ≤ 39 and who were female 12: Patients with > 12 outpatient visits, on csDMARDs and age > 39 13: Patients with > 3 outpatient visits and on csDMARDs |

|||||

| Persistence (months)—Median [95%CI] | 18.4 [17.0–19.6] | 11.1 [10.2–12.2] | |||||

| PsA | |||||||

| Nodes from treea and group characteristics | 4: Patients who were male, not on steroids and treated with GLM | 5: Patients who were male, not on steroids and treated with either ADA, ETA or CZP | 6: Patients who were male and on steroids | 7: Patients who were female | |||

| Persistence (months)—Median [95%CI] | 48.9 [34.7–69.7] | 22.4 [19.9–25.9] | 15.7 [13.3–19.7] | 9.5 [8.8–10.7] | |||

| AS/uSpA | |||||||

| Nodes from treea and group characteristics | 3: Patients who were male and treated with GLM | 4: Patients who were male and treated with either ADA, ETA or CZP | 6: Patients who were female and age ≤ 45 | 7: Patients who were female and age > 45 | |||

| Persistence (months)—Median [95%CI] | 29.5 [25–37.8] | 19.4 [17.9–22.1] | 10.9 [9.8–11.8] | 11.3 [9.7–14.0] | |||

RA rheumatoid arthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis, AS/uSpA ankylosing spondylitis/unspecified spondyloarthritis, csDMARDs conventional systemic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, ADA adalimumab, CZP certolizumab pegol, ETA etanercept, GLM golimumab, CI confidence interval

aThe numbers for the nodes refer to Fig. 2. Steroid treatment refers to treatment the year before treatment initiation

The factors most strongly associated with SC-TNFi persistence differed between RA and spondyloarthropathies as indicated by the first split in the trees (Fig. 2). In RA, the number of outpatient visits the year prior to treatment start was most influential: Patients with few outpatient visits (≤ 3 visits) had better treatment persistence than patients with many outpatient visits (> 3 visits). In contrast, in both AS/uSpA and PsA, sex was the most influential variable. Men had better treatment persistence than women across both indications.

In RA, there was substantial variation after the initial split, and prior csDMARD treatment appeared to be the most influential variable overall (Fig. 2A, D, Table 3): All patients in the group with high SC-TNFi survival were treated with csDMARDs prior to treatment start, whereas two of the four subgroups in the group with low treatment persistence were not. The subgroups with low treatment persistence without prior csDMARDs were characterized by a (1) low age (≤ 39 years), female sex and a high number of outpatient visits (n > 3) and (2) high age (> 39 years) and a very high number of outpatient visits (> 12 visits).

There was also variation in the treatment persistence of SC-TNFi in PsA and AS/uSpA. However, the initial split on sex appeared to be the most important overall with all groups comprising men having higher treatment persistence than all groups comprising women. In PsA (Fig. 2B, E, Table 3), steroids and specific SC-TNFi agent were also associated with treatment persistence in men: The highest treatment persistence was observed in patients without prior steroids treated with golimumab. Among women, no further subgroups were identified after the initial split, and the group with the lowest treatment persistence comprised women. In AS/uSpA (Fig. 2C, F, Table 3), men treated with golimumab had the highest treatment persistence whereas women < 45 years had the lowest treatment persistence.

Time on treatment in the group with the lowest treatment persistence was similar across all three indications: The median time on treatment in these groups ranged from 9.5 [95% CI 8.8–10.7] months in PsA to 11.3 [9.7–14.0] months in AS/uSpA (Table 3). In contrast, there was more variation in time on treatment across the groups with the highest treatment persistence: The median time on treatment in these groups ranged from 18.4 [17.0–19.6] months in RA to 48.9 [34.7–69.7] months in PsA (Table 3).

Comparison Between the Results from the Recursive Partitioning and Cox PH Models

The Cox-PH analyses, presented in Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material, identified more predictors than the recursive partitioning analysis. However, in AS/uSpA, age was not identified as a significant predictor in either the bivariable or multivariable models Cox PH models.

Discussion

This study identified groups with distinct treatment persistence of SC-TNFi in RA, PsA and AS/uSpA. The factors characterizing treatment persistence differed between RA and the two spondyloarthropathy entities. In RA, the groups were comparatively indistinct, but patients without prior csDMARDs were all in the group with the lowest treatment persistence. In contrast, in PsA and AS/uSpA, the groups were more distinct. In both indications, the groups with the highest treatment persistence comprised men treated with golimumab, and the group with the lowest treatment persistence comprised women. Furthermore, in AS/uSpA age was an important factor in women, and in PsA steroids prior to initiation was an important factor in men.

The subgroups with distinct SC-TNFi treatment persistence can be used to identify patients that may require more monitoring and frequent follow-up. However, the causality of some of the factors identified in the analysis is unclear. For example, it is possible that absence of ongoing csDMARD treatment in RA reflect intolerance to methotrexate and that methotrexate therefore cannot be administered concurrently with biologics, resulting in reduced effectiveness and a higher risk of antibodies towards the administered SC-TNFi [21]. Similarly, it is not evident why women have lower treatment persistence than men in PsA and AS/uSpA. It could be a biologic phenomenon but may also reflect a systematic sex difference in attitudes to the risk/benefit profile of SC-TNFi treatment or that SC-TNFis are given partly for symptoms originating from a concurrent chronic widespread pain syndrome (seen more frequently in female patients [39]) that does not respond to anti-inflammatory treatment.

The finding that sex is a predictor for treatment persistence in spondyloarthropathy is consistent with previous studies [40–48]. Contrarily, age and prior steroid use have generally not been associated with treatment persistence in these conditions [22]. One possible reason for this is that these two factors interact with sex and therefore have not been as thoroughly detected in previous studies that have used traditional regression models. We observed higher treatment persistence with golimumab compared to other SC-TNFi in men with AS/uSpA and in men with prior steroid exposure in PsA. Some [49, 50] but not all [51] previous studies have found that golimumab has higher treatment persistence than other TNFis in spondyloarthropathies. Again, one reason for this heterogeneity may be that golimumab has higher treatment persistence in these specific subgroups, effects that may only be observed when interactions are taken into consideration.

In RA, the factor with the strongest association with SC-TNFi treatment persistence was number of outpatient visits the year prior to treatment initiation. One potential reason for this is that the number of rheumatology visits is a proxy for disease activity and difficulties to bring the disease under control: On average, patients with comparatively active disease are expected to see their rheumatologists more often than patients with comparatively inactive disease. Indeed, active disease has generally been associated with low TNFi treatment persistence in the literature [21]. In this study, sex, age and concurrent csDMARD use were associated with SC-TNFi treatment persistence in certain subgroups. Sex and csDMARDs (particularly methotrexate) have previously been associated with TNFi treatment persistence. Such an association has previously not been found with age, potentially reflecting that age was important in a subgroup of patients in the present study and may therefore have gone undetected using traditional regression techniques [21].

The Cox PH models identified a greater number of predictors compared to the recursive partitioning models. Except for sex in AS/uSpA, the predictors included in the partitioning algorithm were identified by the Cox PH models. These findings underscore the relative advantages of each approach. The recognition of age as a significant factor associated with persistence may indicate an interaction with sex. In other words, age may have a more pronounced influence on persistence in women compared to men. This relationship was detected by the recursive partitioning method but would require the inclusion of an interaction term in the Cox PH model. The additional predictors discovered by the Cox models likely stem from two factors. First, the recursive partitioning models employed Bonferroni corrections, effectively decreasing the significance threshold for each subsequent split. Second, the sample size diminishes with each split in the partitioning model, which reduces the statistical power of the analyses. The advantage of the partitioning approach lies in its ability to generate more parsimonious and easily interpretable models. However, a drawback is that important predictors may be overlooked. Additionally, when dealing with categorical variables, recursive partitioning can identify specific categories that exhibit differential outcomes, whereas traditional modeling often relies on a reference class for comparisons, making simultaneous comparison of all treatments challenging.

This study has several limitations. First, it was based solely on administrative data, and we did not have information on potentially important factors for treatment persistence such as smoking, RA disease activity, cytokine levels, patient-reported outcomes or anthropometric measures. Second, we did not have data on the reason for treatment discontinuation. It is possible that some patients did not refill prescriptions because they had a treatment holiday after attaining good response. Third, we only had data on prescription refills and could not ascertain whether patients took their medication or not. Fourth, we did not have information on the indication for the prescription, and it is possible that some patients were misclassified as having IA when they were treated for another disease. It is also possible that patients were misclassified among the different IAs. Furthermore, even though the only two SC-TNFis that became available during the study period were introduced in the final year, we cannot rule out changes in clinical practice over the study period. The study also has important strengths. It relies on data from high-quality nationwide registers with practically complete coverage, and the vast majority of SC-TNFis (> 98%) are dispensed at pharmacies [27] and therefore captured in this study. Furthermore, we relied on observed behavior (prescription refills) instead of self-reported data on treatment discontinuation. We also included all three major IA indications in which SC-TNFis are used, enabling comparisons between indications, and used a statistical learning algorithm that facilitated interpretation of the data.

Further research in this area that could more thoroughly handle methodological challenges, such as interactions and non-continuous effects, would be valuable. A study including clinical and laboratory predictors would be helpful to identify more detailed subgroups, potentially improving discrimination and calibration. Moreover, the same patient cohort could be analyzed using both traditional regression techniques and statistical learning methodologies, informing us on the advantages and disadvantages of the two approaches from a practical perspective. In addition, a study including additional statistical learning methods could elevate the validity of the findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study indicates that women have low treatment persistence in PsA and AS/uSpA whereas male sex and golimumab are associated with high persistence of SC-TNFi treatment in these indications. The factors associated with treatment persistence in RA were less distinct but may comprise disease activity and conventional systemic DMARD treatment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Johan Dalén, Axel Svedbom, Emma Hernlund, Tor Olofsson and Christopher M. Black contributed to the concept and design of this study. Johan Dalén performed the statistical analysis, Johan Dalén, Axel Svedbom and Emma Hernlund summarized the results, Johan Dalén and Axel Svedbom drafted the manuscript. Johan Dalén, Axel Svedbom, Emma Hernlund, Tor Olofsson and Christopher M. Black reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Prior Publication

The current work is an update and extension of a previous study. Preliminary results were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in Atlanta, GA, USA, November 8–13, 2019 [52]. For this study, the data was updated and the novel analyses were conducted by IA indication.

Disclosures

Christopher M. Black is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and holds stock and options in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. Johan Dalén is an employee of ICON plc, while Emma Hernlund, and Axel Svedbom were employees of ICON plc in conjunction with the development of this manuscript. ICON plc were paid consultants to Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, in conjunction with the development of this manuscript. ICON plc has received funding from several pharmaceutical companies involved in the marketing products for treatment of inflammatory arthritis. At the time of manuscript submission, Emma Hernlund and Axel Svedbom are affiliated with the Swedish Dental and Pharmaceuticals Benefits Agency and the Karolinska Institute, respectively. Axel Svedbom reports consulting fees from Abbvie, employment and consulting fees from ICON plc, Eli Lilly AB, Novartis AB and lecture fees from Janssen and UCB. Tor Olofsson is a specialist in rheumatology at Skåne University Hospital and has performed consulting tasks for MSD related to the present work and for Eli Lilly, unrelated to the present work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Due to the retrospective non-interventional study design and the applicable laws and regulations pertaining to the utilized data sources, informed consent and participant consent were not applicable. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and, prior to initiation, ethics approval was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (approval number 2019-02774).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to applicable laws and regulations pertaining to Swedish administrative and clinical data available for research.

References

- 1.Lipton S, Deodhar A. The new ASAS classification criteria for axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis: promises and pitfalls. Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;7(6):675. doi: 10.2217/ijr.12.61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handout on Health: Rheumatoid Arthritis. 2014, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

- 3.Braun J, et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):896–904. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.151027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gossec L, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):4–12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus T, Callahan LF. What is the natural history of rheumatoid arthritis? Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1993;19(1):123–151. doi: 10.1016/S0889-857X(21)00171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neovius M, et al. Nationwide prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and penetration of disease-modifying drugs in Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(4):624–629. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Söderlin MK, et al. Annual incidence of inflammatory joint diseases in a population based study in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(10):911–915. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.10.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haglund E, et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthritis and its subtypes in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):943–948. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.141598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Exarchou S, et al. The prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in Sweden: a Nationwide Register Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(Suppl):S17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gjertsson I et al. Riktlinjer för läkemedelsbehandling vid reumatoid artrit. Svensk Reumatologisk Förening, 2019.

- 11.Helena Forsblad d’Elia TH, Ulf L, Agnes S, Wallman JK, Wedrén S. Riktlinjer för läkemedelsbehandling vid axial spondylartrit och psoriasisartrit 2022. Svensk Reumatologisk Förening; 2022.

- 12.Stevens SR, Chang TH. TNF-alpha inhibitors. Springer; 2006. History of development of TNF inhibitors; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meissner B, et al. Switching of biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a real world setting. J Med Econ. 2014;17(4):259–265. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.893241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todoerti M et al. Switch or swap strategy in rheumatoid arthritis patients failing TNF inhibitors? Results of a modified Italian Expert Consensus. Rheumatology. 2018;57(Supplement_7):vii42–vii53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Aletaha D, Smolen, JS. Effectiveness profiles and dose dependent retention of traditional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. An observational study. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(8):1631–1638. [PubMed]

- 16.Fries J. Effectiveness and toxicity considerations in outcome directed therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1996;44:102–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pincus T, et al. Longterm drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in seven rheumatology private practices: I. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(12):1874–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon GW, et al. Clinical outcomes and biologic costs of switching between tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Ther. 2016;33(8):1347–1359. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0371-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu T, et al. Cost of biologic treatment persistence or switching in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(8 Spec No.):SP338–SP345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanderpoel J, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs associated with switching biologics in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2019;41(6):1080–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letarouilly J-G, Salmon J-H, Flipo R-M. Factors affecting persistence with biologic treatments in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2021;20(9):1087–1094. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2021.1924146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murage MJ, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Patient Prefer Adher. 2018;12:1483. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S167508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Löfvendahl S, Schelin ME, Jöud A. The value of the Skåne Health-care Register: prospectively collected individual-level data for population-based studies. Scand J Public Health. 2020;48(1):56–63. doi: 10.1177/1403494819868042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludvigsson JF, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–667. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Elm E, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludvigsson JF, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welfare NBOHA. Quality declaration, statistics on pharmaceuticals for 2018. 2019.

- 28.Welfare NBOHA. Cause of death register. 2019. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/register/alla-register/dodsorsaksregistret/bortfall-och-kvalitet/.

- 29.Dalén J, et al. Treatment persistence among patients with immune-mediated rheumatic disease newly treated with subcutaneous TNF-alpha inhibitors and costs associated with non-persistence. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(7):987–995. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalén J, et al. Second-line treatment persistence and costs among patients with immune-mediated rheumatic diseases treated with subcutaneous TNF-alpha inhibitors. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(12):2049–2058. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3825-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalén J, et al. Treatment persistence in patients cycling on subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in inflammatory arthritis: a retrospective study. Adv Ther. 2022;39(1):244–255. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01879-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer JA, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charlson ME, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aslam F, Khan NA. Tools for the assessment of comorbidity burden in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Med. 2018;5:39. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J Comput Graph Stat. 2006;15(3):651–674. doi: 10.1198/106186006X133933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook EF, Goldman L. Empiric comparison of multivariate analytic techniques: advantages and disadvantages of recursive partitioning analysis. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37(9–10):721–731. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdi H. Bonferroni and Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage; 2007.

- 38.Bonferroni C. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilita. Pubblicazioni del R Istituto Superiore di Scienze Economiche e Commericiali di Firenze. 1936;8:3–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mogard E, et al. Chronic pain and assessment of pain sensitivity in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from the SPARTAKUS cohort. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(11):1672–1679. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glintborg B, et al. Clinical response, drug survival and predictors thereof in 432 ankylosing spondylitis patients after switching tumour necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1149–1155. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glintborg B, et al. Predictors of treatment response and drug continuation in 842 patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor: results from 8 years' surveillance in the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):2002–2008. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kristensen LE, et al. Presence of peripheral arthritis and male sex predicting continuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: an observational prospective cohort study from the south swedish arthritis treatment group register. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(10):1362–1369. doi: 10.1002/acr.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deodhar A, Yu D. Switching tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis. In: Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Favalli EG, et al. Eight-year retention rate of first-line tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in spondyloarthritis: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(6):867–874. doi: 10.1002/acr.23090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barata C, et al. Predicting biologic therapy outcome of patients with spondyloarthritis: joint models for longitudinal and survival analysis. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9(7):e26823. doi: 10.2196/26823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Acurcio FDA, et al. Comparative persistence of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in ankylosing spondylitis patients: a multicenter international study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(4):677–686. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2020.1722945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D'Angelo S, et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: an Italian real-life retrospective study. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1497. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krajewski F, et al. Drug maintenance of a second tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor in spondyloarthritis patients: a real-life multicenter study. Jt Bone Spine. 2019;86(6):761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.González-Fernández M et al. Persistence of biological agents over an eight-year period in rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis patients. Farmacia Hospitalaria. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Egeberg A et al. Drug survival of biologics and novel immunomodulators for rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis-A nationwide cohort study from the DANBIO and DERMBIO registries. In: Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Yu C-L, Yang C-H, Chi C-C. Drug survival of biologics in treating ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence. BioDrugs. 2020;34(5):669–679. doi: 10.1007/s40259-020-00442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hernlund E, et al. Decision tree analysis to identify inflammatory arthritis patient subgroups with different levels of treatment persistence with first-line subcutaneous TNF-alpha inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(Supplement 10):5073–5074. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to applicable laws and regulations pertaining to Swedish administrative and clinical data available for research.