Abstract

Background

Post-operative physiotherapy is a major component of the effectiveness of knee replacement. Adequate rehabilitation protocols are required for better functional outcomes. With the advent of smartphones and smartwatches, the use of telerehabilitation has increased recently. This study aims to compare tele rehabilitation using various mobile-based applications to conventional rehabilitation protocols.

Methods

From Jan 2000 to Jun 2022, all the RCTs from SCOPUS, EMBASE and PUBMED comparing patient-related outcome measures between the smartphone-based app and conventional rehabilitation protocols were scanned and seven studies meeting the eligibility criteria were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The quantitative analysis compared outcomes using the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), the knee society function score (KSFS), the active range of motion (AROM), Euro-Qol-5D-5L, and MUA. The qualitative analysis compared VAS, NRS, and Time up and go (TUG).

Results

The study shows statistically significant improvement in traditional rehabilitation over app based on KSFS score (M.D.: 6.05, p = 0.05) and AROM on long-term follow-up (12 months) (M.D.: 2.46, p = 0.02). AROM was insignificant on 3 months or less follow-up. NRS and VAS were found to be statistically better in app-based groups. No statistically significant results were seen on KOOS, Euro-Qol-5D-5L, MUA and TUG. 90 days of readmission and a number of physiotherapy visits were more in conventional groups. No difference was seen in single-leg stance and satisfaction rates.

Conclusions

The present review highlights improved early pain scores and comparable patient-reported outcome analysis at a short-term follow-up period among patients receiving mobile app-based rehabilitation. However, knee range of motion and KSFS score achieved after surgery is analysed to be better with traditional rehabilitation at the one-year end follow-up period.

Keywords: Smartphone application, Mobile-based rehabilitation, App-based rehabilitation, Rehab, Total knee arthroplasty, Outcomes, Meta-analysis

1. Introduction

The number of people undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for various indications is increasing yearly. The trend is expected to increase with advancements in the medical field and more readily available facilities. It is estimated that a total of 3.48 million/year TKA will be done in the USA alone by 2030.1 However, 1/5th of patients (about 20%) develop chronic knee pain, poor functional outcomes, and low satisfaction rates following TKA.2 The patient outcome has been a significant concern for surgeons, as the surgery aims to improve knee function and make the joint pain-free. The cause of pain could be implant-related (loosening, patellofemoral mal-alignment), or it could be due to soft tissue inflammation and damage because of retinacular compromise, insufficient blood supply, or medial and lateral over-releases.3,4 Improvising the implant design as per the patient's fit with an effective post-operative physiotherapy protocol may be necessary for improving the overall patient-reported outcomes.

Post-operative physiotherapy aims to increase the strength of quadriceps musculature, range of motion (ROM), and early return to normalcy. Studies have proved the efficacy of physiotherapy in reducing hospital stays in,5,6 fewer complications, improving quality of life in,7 and reducing pain.8 Many physiotherapy protocols are available, including passive motion, rapid rehabilitation, and tele rehabilitation using remote devices and mobile-based physiotherapy applications. However, literature support is scarce regarding which protocol is more effective with better postoperative outcomes.

This systematic review and meta-analysis are aimed at discovering whether the modern app-based rehabilitation process post-knee arthroplasty (KA) has any additional benefits compared to its traditional counterparts, according to the published reports on comparative studies utilizing the two different rehabilitation methods.

2. Material and methods

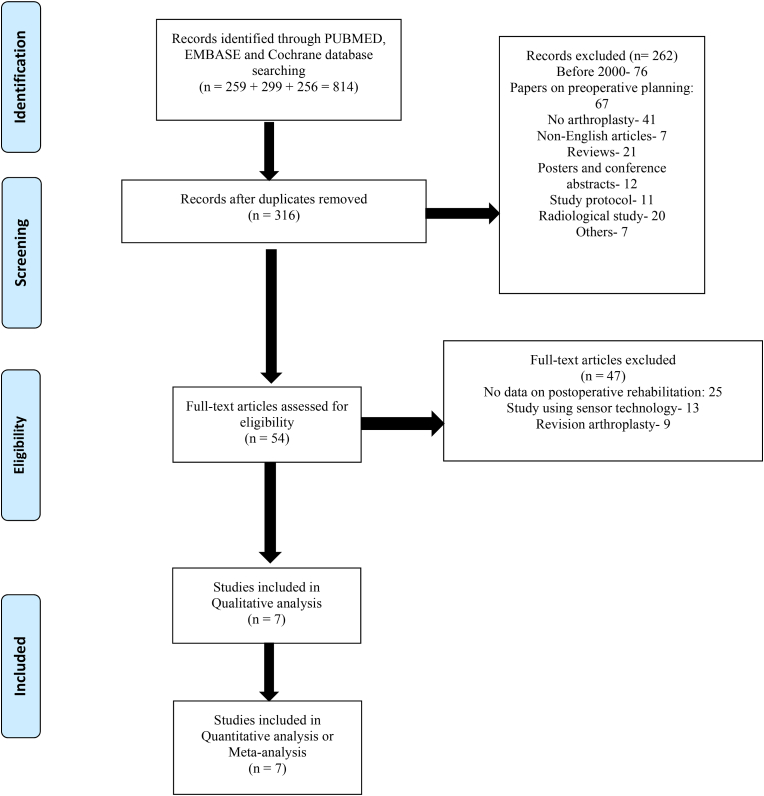

This present review has been conducted in terms of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA - 2020) protocol as depicted by the Cochrane Review methods (Figure-1). The research protocol was registered with PROSPERO with the unique identification number of CRD42022336069 on June 08, 2022.

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow chart.

2.1. Literature search strategy

Three electronic databases namely SCOPUS, PUBMED, and EMBASE were thoroughly searched between January 2000 and up until June 30, 2022 and all relevant articles were selected. The present study included only prospective randomised controlled trials, with patients undergoing knee arthroplasty, either partial or total knee, and post-operatively who received conventional or smartphone application-based rehabilitation for analysis. Regarding the publication year, there were no limitations. Studies evaluated classic or modern smartphone applications for post-KA rehabilitation with a minimum of one PROM or range of motion (ROM). Table 1 provides more details on the search process, including the search phrases employed. To include the papers not found in the electronic databases in the final list, references within the articles that were primarily shortlisted were also searched.

Table-1.

Search methodology used in the review.

| Indexes searched | Search terms used | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | (Knee arthroplasty OR Knee replacement) AND (Rehabilitation OR physiotherapy) AND (Mobile application OR application OR app-based OR software) | 259 |

| Embase | (‘knee replacement'/exp OR ' (knee arthroplasty)') AND (rehabilitation OR ‘physiotherapy'/exp) AND ‘mobile application'/exp OR application OR app-based OR ‘software'/exp) | 299 |

| Cochrane | (Knee arthroplasty OR Knee replacement) AND (Rehabilitation OR physiotherapy) AND (Mobile application OR application OR app-based OR software OR compliance) in Title and Abstract Keywords (Word variations has been searched) |

256 |

The first (AKC) and third author (A.K) conducted the initial search. The title with the respective abstracts, were initially scrutinised by the authors to see if they addressed the pertinent study issue. This was followed by the full texts review and final inclusion of the irrelevant literature. If there were any disagreements, these were discussed and assessed by the senior most author (R.B·K), who then created the final list. The last papers' complete texts were retrieved, and all the included articles' content was examined for a future systematic review.

2.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria and data selection

The present systematic review included only original randomised comparative clinical trials published in the English language that compared at least one PROMs. Exclusion criteria included those written in any other language, if the outcomes of interest were not reported, any series with only one rehabilitation method after-TKA were mentioned, any isolated case reports, and studies including revision arthroplasties. Seven randomised comparative studies were selected finally based on the laid down inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Defining the various outcomes of interest

The review included a smartphone or a wearable smart-watch-based application for post-knee replacement rehabilitation against the traditional methods of rehabilitation after TKA. Initial data synthesis was based on the study types, patient characteristics, the follow-up period, resource utilization rate, and clinical outcomes with a minimum of one patient-reported outcome measure scores.

2.4. Quality of evidence

Each included study's methodological quality was assessed using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Controlled Intervention Studies (RCTs). The NIH quality evaluation method has been extensively utilised for several research and is regarded as an important tool for evaluating study quality.9 Based on the questionnaire checklist, each eligible comparison study was rated as having good (>50% weightage in the form of Yes, to the total numbers of questions), fair (equal to 50% weightage in the form of Yes, to the total numbers of questions), or low quality (<50% weightage in the form of Yes, to the total numbers of questions) by two distinct authors (A.K and S·B). This has been depicted in Table 2. The opinions of a third author (B·S.R.) were sought in the event that the two accessors could not come to an agreement after debate. According to this quality assessment tool, all seven studies were of good quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies according to NIH tools for controlled intervention studies.

| Author (year) | CK1 | CK2 | CK3 | CK4 | CK5 | CK6 | CK7 | CK8 | CK9 | CK10 | CK11 | CK12 | CK13 | CK14 | Quality Of The Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bini et al. 201619 | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Good |

| Culliton et al. 201818 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good |

| Hardt et al. 201815 | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good |

| Timmers et al. 201914 | Y | N | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good |

| Crawford et al. 202117 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Good |

| Backer et al. 202116 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Good |

| Tripuraneni et al. 202113 | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Good |

Abbreviations used – Yes – Y, No–N, NR – Not reported CK 1. Was the study described as randomised, a randomised trial, a randomised clinical trial, or an RCT? CK 2. Was the method of randomization adequate (i.e., use of randomly generated assignment)? CK 3. Was the treatment allocation concealed (so that assignments could not be predicted)? CK 4. Were study participants and providers blinded to treatment group assignment? CK 5. Were the people assessing the outcomes blinded to the participants' group assignments? CK 6. Were the groups similar at baseline on important characteristics that could affect outcomes (e.g., demographics, risk factors, co-morbid conditions)? CK 7. Was the overall drop-out rate from the study at endpoint 20% or lower of the number allocated to treatment? CK 8. Was the differential drop-out rate (between treatment groups) at endpoint 15% points or lower? CK 9. Was there high adherence to the intervention protocols for each treatment group? CK 10. Were other interventions avoided or similar in the groups (e.g., similar background treatments)? CK 11. Were outcomes assessed using valid and reliable measures, implemented consistently across all study participants? CK 12. Did the authors report that the sample size was sufficiently large to be able to detect a difference in the main outcome between groups with at least 80% power? CK 13. Were outcomes reported or subgroups analysed prespecified (i.e., identified before analyses were conducted)? CK 14. Were all randomised participants analysed in the group to which they were originally assigned, i.e., did they use an intention-to-treat analysis?.

2.5. Data synthesis

The first and second authors, independently extracted data from the studies selected in this review. The data extracted for the review included the first author of the included studies, the year of publication, study design, total number of patients, each group of patients and their characteristics (the mean age, sex ratio), nature of comparators, the data on the application used for rehabilitation if used, and the patient-reported outcomes as mentioned previously.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All data were initially documented using a Microsoft (MS) Excel spreadsheet. Standard deviations (SD) and absolute numbers and percentages were used to express categorical variables and all continuous variables. If enough information could be gleaned from the included studies, a meta-analysis of the outcomes were conducted. Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4.1 (the Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration) software for MAC was used to create funnel plots, forest plots for meta-analysis. The meta-analysis was conducted using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The dichotomous variables were reported as risk ratios with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). If the variables were constantly stated as mean with SD, the inverse variance model was applied. The I2 index was used to measure the heterogeneity. A fixed-effects model would be recommended if the I2 value was less than 50%, and a random-effects model would be needed if the I2 value was greater than 50% or there was significant heterogeneity. Whenever practicable, a subgroup analysis was taken into account when the degree of study heterogeneity was high. The P-value greater than 0.05 was regarded as inconsequential and statistically comparable, whereas a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

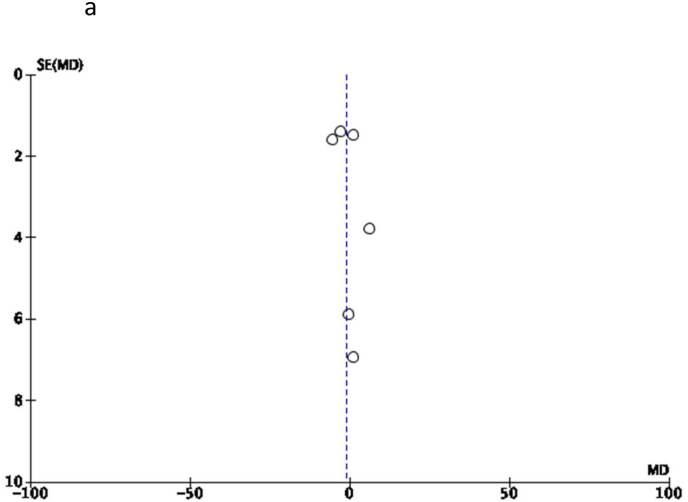

814 articles were found in the initial literature search thanks to precise search phrases (Table 1). 262 articles were caused by duplicates and the initial exclusion of articles. Following the title and abstract screening, 54 full-text studies were carefully screened and finally listed using the inclusion criteria described above. After eliminating 47 full-text papers, 7 RCTs were left, which were explained by the exclusion criteria and particular causes. This systematic analysis examined 1335 patients in total across all seven prospective RCTs. Fig. 1 depicts the study inclusion procedure (PRISMA flow diagram). The quality analysis of the evidence was carried out using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool (Table 2). Funnel Plots are diagrammatically represented in Fig. 2B, Fig. 2C, Fig. 2D, Fig. 2A(a-d), suggesting that the included studies were within the permissible limit of heterogenicity and publication bias as the study data were falling within the boundaries of the 95% CI.

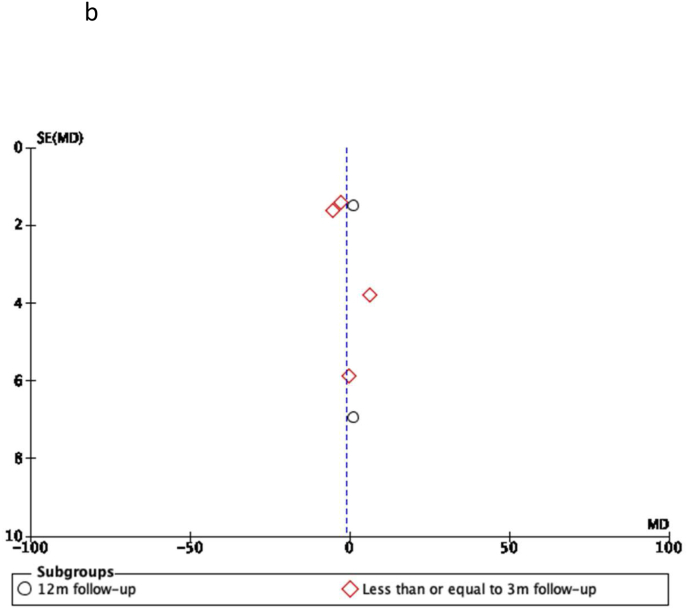

Fig. 2B.

KOOS subgroup analysis according to follow-up periods.

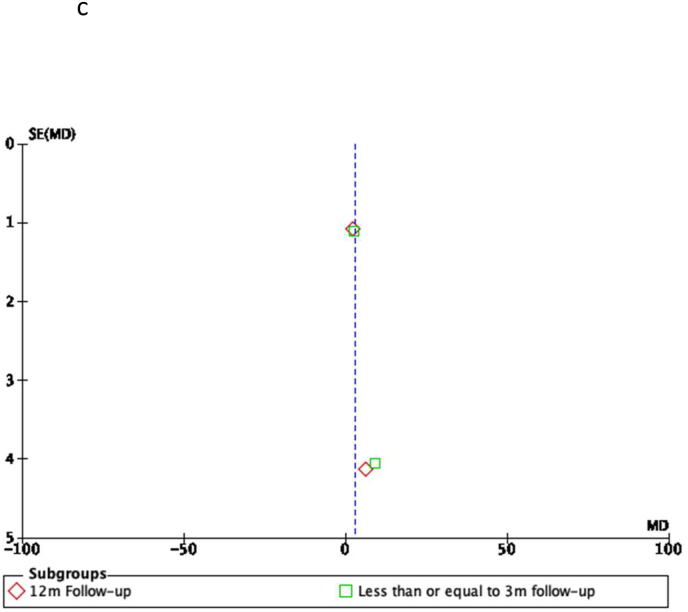

Fig. 2C.

Arom.

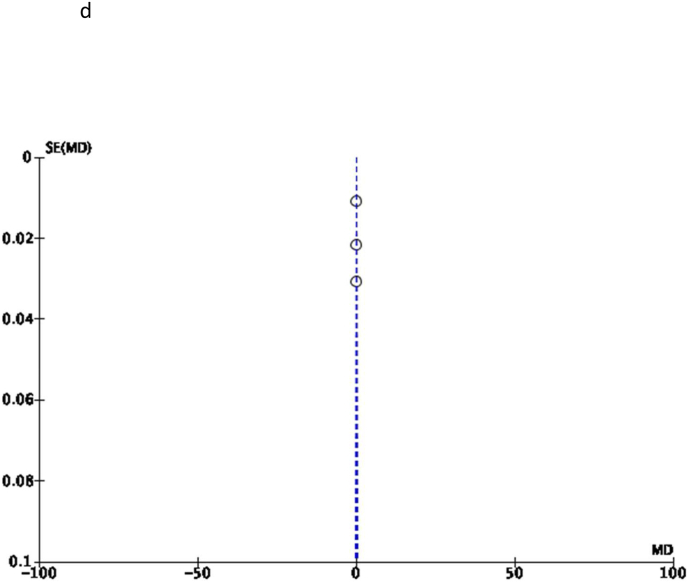

Fig. 2D.

Euro-qol-5d-5L.

Fig. 2A.

KOOS.

3.2. Study characteristics

All seven trials were prospective randomised controlled studies. The review included 1364 patients, 661 patients in the application-based rehabilitation group or intervention group (IG) versus 703 patients in the traditional rehabilitation group or the control group (CG), with 38.7% males undergoing TKA. The mean BMI of the study cohorts were not mentioned by Tripuraneni et al. and Timmers et al.10,and 11 The study by Tripuraneni et al. did not mention the mean age for their study group of patients. The individual study characteristics with the different follow-up periods have been mentioned in Table 3. Two studies suggested GenuSport mobile-based application,12,13 and two studies used Mymobility mobile application for rehabilitation post-TKA.10,17 The other three articles suggested the Patient Journey App,11 an online e-learning tool,14 and the CaptureProof app15 for rehabilitation. Studies were categorised according to the follow-up of 12 months and less than or equal to 3 months. A minimum of 12 months of follow-up were mentioned in three studies13,16,18 and all others had a minimum follow-up period of less than or equal to 3 months.

Table 3.

Study characteristics.

| Study | Type of study | Sample size |

M/F |

Mean age ± SD (years) |

Mean BMI (kg/m2) |

Mobile application | Outcome measures | Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG | CG | IG | CG | IG | CG | IG | CG | |||||

| Backer et al., 202116 | RCT | 20 | 15 | 14/21 | 64.37 ± 9.32 | 32.95 ± 6.16 | GenuSport | VAS score; AROM; Time of 10 m walk; KOOS; KSS | Short-term: 6.74 ± 0.85 days Long term: 23.51 ± 1.63 months |

|||

| Tripuraneni et al. 202113 | RCT (multicentre) | 153 | 184 | 141/196 | – | – | Mymobility | AROM; MUA; KOOS, JR; EQ-5D-5L | 12 months | |||

| Crawford et al. 202117 | RCT (multicentre) | 160 | 185 | 54/106 | 75/110 | 63.2 ± 8.6 | 64.5 ± 8.9 | 32.2 | 31.3 | Mymobility | KOOS score; EQ-5D-DL score; single leg stance; Timed Up and Go test; passive flexion | 3 months |

| Timmers et al. 201914 | RCT | 114 | 99 | 40/74 | 39/60 | 64.74 ± 7.57 | 65.63 ± 7.9 | – | Patient Journey App | NRS scores; KOOS score; EuroQol 3-level questionnaire; VAS scores | 4 weeks | |

| Culliton et al. 201818 | RCT | 167 | 178 | 69/98 | 55/123 | 64 ± 8 | 63 ± 9 | 33 ± 8 | 33 ± 7 | Online e-learning tool | KSS; KOOS; SF-12; HADS; PCS; SRPQ; UCLA Activity score; SCQ | 12 months |

| Hardt et al. 201815 | ‘RCT | 33 | 27 | 15/18 | 11/16 | 66.3 ± 9.3; | 68.5 ± 10.3 | 30.5 ± 5.2 | 32.2 ± 6.2 | GenuSport | AROM; NRS scale for pain at rest & in motion; KOOS; KSS; Length of stay; MKC; GenuSport training count | 7 ± 1 days |

| Bini et al., 2016 | RCT | 14 | 15 | 6/7 | 9/6 | 62.9 | 63.6 | – | CaptureProof | KOOS; VAS; PCS; MCS | 3 months | |

IG – Intervention group, CG – Control group, SD: Standard deviation; RCT: Randomised Controlled Trial; VAS: Visual Analog scale; AROM: Active Range of motion; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis outcome score; KSS: Knee Society Score; MUA: Manipulation under anaesthesia; KOOS, JR: KOOS, Joint replacement; EQ-5D-DL: EuroQol Five Dimensions Five Levels; TKR/TKA: Total Knee replacement/arthroplasty; KOOS-QOL: KOOS- Quality of life; HEP: home exercise plan; UKA: Unicondylar Knee Arthroplasty; VERA: Virtual Exercise Rehabilitation Assistant; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index; AMPAC: Boston University Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care score; SUS: system usability scale; SF-12: Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, version 2; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale; PCS: Pain Catastrophizing scale; SRPQ: Social Role Participation Questionnaire; UCLA: University of California at Los Angeles; SCQ: Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire; NRS: Numeric Rating scale;MKC: Mean Knee circumference; PCS: Physical component scores; MCS: Mental component scores.

3.3. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)

All PROMs were expressed in terms of means and SD (Table 4). Where ever some consistent scores were mentioned in the respective studies included in this review, a meta-analysis was planned, and statistical significance was evaluated. In their article, Culliton et al.14 did not mention the SDs or the median and range for all their PROMs. Hence the same was excluded during meta-analysis.

-

a

Knee injury and Osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)

Table 4.

Compilation of PROM in various studies.

| S. No. | Author (year of publication) | Group | KOOS | KSS | NRS-pain | VAS | AROM | MUA | Length of Stay | EQ-5D-5L | EQ-5D-3 VAS | Time up and go | Single leg stance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bini et al. 201619 | Control | −17.251, 14.201 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | −17.591, 17.148 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Culliton et al. 201818 | Control | 72.36 | 32.34 | |||||||||

| Interventional | 71.28 | 31.12 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Hardt et al. 201815 | Control | 41.4, 14.3 | 37, 16 | 4, 1.5 | 67, 18 | 6.9, 1 | 26.3, 16.7 | |||||

| Interventional | 47.6, 14.8 | 42, 14 | 3.5, 1 | 76, 12 | 6.6, 1 | 23.6, 15.9 | |||||||

| 4 | Timmers et al. 201914 | Control | 43.08, 12.96 | 4.6, 3.2 | 0.67, 0.21 | 69.59, 16.38 | |||||||

| Interventional | 37.61, 10.17 | 3.8, 3.3 | 0.65, 0.24 | 67.42, 19.56 | |||||||||

| 5 | Crawford et al. 202117 | Control | 72.2, 13.3 | 118.8, 11.7 | 9/185 | 0.8, 0.2 | 10.6, 5.4 | 21.6, 19.9 | |||||

| Interventional | 69.4, 12.8 | 121.2, 8.9 | 4/160 | 0.8, 0.2 | 9.6, 3.6 | 22.9, 21.1 | |||||||

| 6 | Backer et al. 202116 | Control | 66.84, 19.15 | 67.67, 16.57 | 1.865, 1.73 | 70.87, 12.19 | |||||||

| Interventional | 68.06, 21.7 | 76.32, 16.49 | 1.77, 1.9 | 77.15, 11.84 | |||||||||

| 7 | Tripuraneni et al. 202113 | Control | 82.1, 13.4 | 117.2, 11.3 | 11/184 | 0.9, 0.1 | |||||||

| Interventional | 83.1, 13.8 | 119.4, 8.3 | 6/153 | 0.9, 0.1 |

Foot note - All values expressed as Mean, and Standard Deviation (SD). Absolute numbers mentioned where ever applicable.

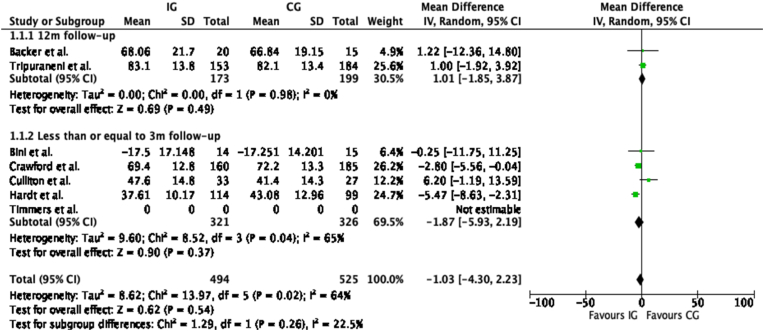

Six studies13,15, 16, 17, 18, 19 compared the two groups of patients, either going for app-based or traditional rehabilitation after TKA. Subgroup analysis was done based on a follow-up period of 12 months and less than or equal to 3 months did not reveal any significant differences. At 12 months of follow-up (I2 0%, Mean difference 1.01, 95% CI [–1.85, 3.87], p - 0.98; ►Fig. 3) and less than or equal to 3 months follow-up (I2 65%, Mean difference −1.87, 95% CI [–5.93, 2.19], p - 0.37; ►Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

KOOS ma

The pooled cumulative data analysis revealed no statistical difference between both the two groups (I2 - 22.5%, Mean difference −1.03, 95% CI [–4.30, 2.23], p - 0.26; ►Fig. 3).

-

b

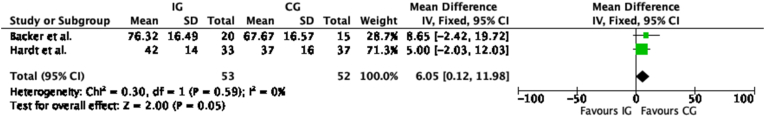

Knee society function scores (KSFS)

Two studies15,16 evaluated the KSFS during the follow-up period. The pooled data analysis revealed that traditional rehabilitation suggested statistically significant improvement over app-based rehabilitation after TKA (I2 - 0%, Mean difference - 6.05, 95% CI [0.12, 11.98], p - 0.05; ►Fig. 4).

-

c

Active range of Motion (AROM)

Fig. 4.

KSFS ma

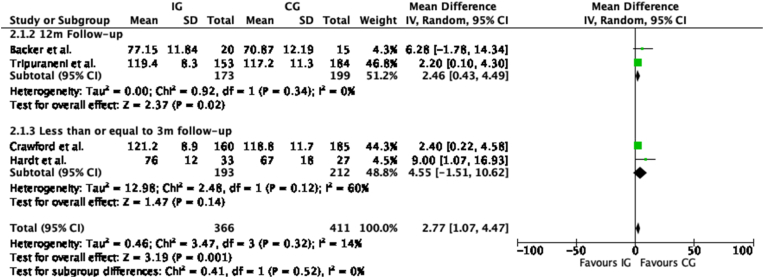

Four studies13,15, 16, 17 evaluated the active range of motion post-rehabilitation after TKA in two different groups of patients. Subgroup analysis was done based on the two different follow-up periods and whether it affects the outcome post-surgery. At 12 months of follow-up (I2 - 0%, Mean difference - 2.46, 95% CI [0.43, 4.49], p - 0.02; ►Fig. 5) there was statistically significant better AROM favouring the conventional rehabilitation process post-TKA. However, at less than or equal to 3 months follow-up period, the results (I2 - 60%, Mean difference - 4.55, 95% CI [–1.51, 10.62], p - 0.14; ►Fig. 5) were insignificant.

Fig. 5.

Arom ma

The combined pooled data meta-analysis without any subgroup analysis also revealed that the use of app-based rehab is statistically inferior to conventional rehabilitation method (I2 - 14%, mean difference 2.77, 95% CI [1.07, 4.47], p - 0.001; ►Fig. 5) but considering the subgroup differences (I2 - 0%, p - 0.52; ►Fig. 5) the result was statistically insignificant.

-

d

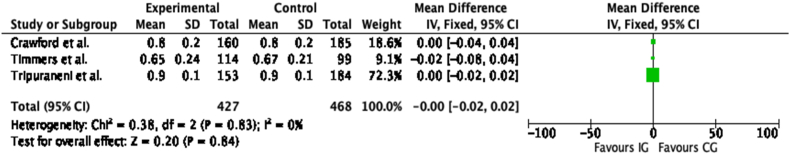

EuroQol-5D-5L

Three studies13,14,17 evaluated the quality of life using the EuroQol-5D-5L comparative outcome tool between the two groups of patients receiving rehabilitation after TKA. Pooled data analysis, did not reveal any statistically significant difference (I2 - 0%, Mean difference - 0, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.02], p - 0.84; ►Fig. 6).

-

e

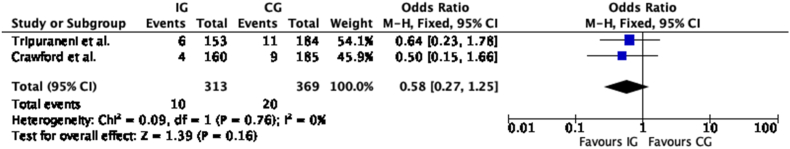

Manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA)

Fig. 6.

Euro-qol-5d-5L ma

Two studies13,17 evaluated MUA numbers between the two groups of patients. Although the numbers of patients needing MUA for stiffness post-surgery were more in the traditional rehabilitation group when compared with app-based rehabilitation, it did not reach a statistical significance (I2 - 0%, odds ratio - 0.58, 95% CI [0.27, 1.25], p - 0.16; ►Fig. 7).

-

f

Other PROMs, satisfaction rates, and resource utilization or readmission

Fig. 7.

Mua ma

Other PROMS mentioned in the studies were inconsistent, so a meta-analysis was not conducted. All PROMs have been outlined in Table 4. Previous studies have evaluated the VAS for pain and NRS grade as non-parallel and hence could not be combined.14, 15, 16

NRS-pain was used by Hardt et al. and Timmers et al. in their studies. Hardt et al.15 mentioned that according to the intention to treat analysis, the NRS score for pain at rest (3.1 vs. 3.2; p = non-significant) and during activities (4.1 vs. 5.1; p = 0.006) was better in the app-based rehabilitation group than in the conventional group. Timmers et al.14 also suggested better pain scores at four weeks follow-up at rest (3.45 vs. 4.59; p = 0.001), during activity (3.99 vs. 5.08; p < 0.001), and at night (4.18 vs. 5.21; p = 0.003) in the app-based rehabilitation group. VAS for pain was used by Backer et al.16 in their study, and it revealed statistically significant better scores at rest (2.65,0.82 vs. 3.35, 1.58; p = 0.033) and during activities (4.03, 1.26 vs. 5.05, 1.21; p = 0.021) in the app-based rehabilitation group at short-term, however, it was insignificant both at rest and during activities (p = 0.979) during the long-term follow-up.

The timed up-and-go (TUG) test was noted by Hardt et al.15 and Crawford et al.17 in their respective studies. Both study did not reveal any statistically significant report of the TUG test between the two groups at their final follow-up. Single leg stance was noted by Crawford et al. and it did not suggest any statistically significant result.

Culliton et al.18 analysed the satisfaction rates in either of the two groups of patients receiving two different modalities of rehabilitation post-TKA. The study suggested that 121 of 154 (78.6%) were satisfied in the app-based rehabilitation group versus 129 of 165 (78.2%) were satisfied in the conventional rehabilitation group. Crawford et al. suggested that 90 days readmission rates were noted to be higher in the control group than in the intervention or app-based rehabilitation group (10/185 vs. 5/160). Also, they suggested that the number of physiotherapy visits was more in the traditional rehabilitation group (174/185; 93.9%) than in the app-based rehabilitation group (105/160; 65.8%).

4. Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a significantly better one-year active range of motion in the conventional rehabilitation group of patients after TKA compared to app-based rehabilitation. The study further suggests better short-term pain scores in app-based rehabilitation, although the pain level was statistically insignificant at the end of 1-year follow-up. PROMs, when analysed, presented comparable outcomes in both groups of patients, with higher chances of manipulation under anaesthesia, resource utilization, and readmission rates in conventional rehabilitation after TKA. KSFS score was found to be statistically significant in the IG group marginally, however, no clinical comment could be made based on the two studies. AROM was found statistically significant in the CG group in four studies suggesting better results under supervision compared to app-based physiotherapy. The two groups of patients noted similar post-surgery satisfaction rates and comparable quality of life scores.

Contemporary research on total knee replacement surgeries is being targeted towards increasing post-surgery satisfaction and overall outcome measures. One critical aspect in improving post-replacement outcomes is supervised and individualized rigorous rehabilitation. Osteoarthritis of the knees is a disease that involves not only bone-to-bone affection but also has an essential aspect of quadriceps weakness and dynamic balance.16, 17, 18 Hence with surgery, the bony pathology is corrected by replacing it with a biomechanically sound metal surface, but soft-tissue and knee musculature strengthening become important after surgery. The use of a tourniquet has shown to affect the extensor mechanism at least temporarily, secondary to reperfusion and rhabdomyolysis.19 Intra-operatively soft-tissue handling during knee balancing also triggers a local inflammatory process that stimulates the pain regeneration pathway, inversely affecting the overall quadriceps recovery and early mobilisation process.20 Conventional rehabilitation has been tried and tested over time and tailored to post-surgery patient demands. New rehabilitation methods like tele rehabilitation21 or smartphone app-based rehabilitation are increasingly being incorporated into regular practice. These newer rehabilitation modalities are equally good and extremely useful for patient engagement and compliance after replacement surgeries, especially during covid lockdowns and the post-covid era. Bauwens et al. showed the usefulness of smartphone-based apps following ACL reconstruction during covid lockdown.22 Remote access to healthcare has been proven beneficial, but its actual advantages need to be judged, and hence this review becomes reasonably crucial in this current time.

Extension Langfield,23 knee stiffness,24 and flexion contractor field25 post-TKA are of essential concern, and to avoid these, constant motivation, encouragement, and supervised physiotherapy have been often considered critical. Knee stiffness post-arthroplasty, if not treated early, is challenging to treat and can lead to an increased need for repeat surgeries held26 and arthroscopic releases.27 However, previous studies have also suggested unsupervised home-based rehabilitation can be equally beneficial for achieving post-operative goals and milestones.28, 29, 30 Hence, the supervised or unsupervised role of physiotherapy has always remained highlighted post-TKA and the standard of a care management protocol for achieving an adequate range of motion after surgery. The present study favours that conventional rehabilitation protocol may benefit long-term or one-year follow-up in helping patients attain an optimal range of motion. The current review failed to identify any favourable PROM between application-based rehabilitation and conventional methods. Previous studies, however, have suggested an extensive consideration of economic drain because of repeated post-arthroplasty visits for the need for physiotherapy.31,32 Yayac et al. most recently pointed out that home-based physiotherapy costs almost 200 dollars more than outpatient physiotherapy visits.33 Hence if medicine can be appropriately integrated with technological advancements, similar postoperative outcomes are achievable with lesser healthcare and economic drain.34 Crawford et al. similarly highlight a rate of 93.9% in physiotherapy visits in their cohort of patients receiving post-TKA conventional rehabilitation compared to 65.8% in the app-based rehabilitation group. Studies suggest with these patient-oriented smartphone applications, smart-watches can also be paired, and the regular data regarding patients' activities, including the step, counts, stairs taken, and heart rates, can be monitored remotely. In all such patients where there is a lack in achieving timely after-surgery goals, various supervised targeted healthcare facilities can be offered.

Thus, mobile-application-based rehabilitation may reduce physiotherapy visits, healthcare burden, and economic drain. Still, compared to patient-centric outcome analysis, it suggests comparable results to conventional rehabilitation methods.

The present systematic review is not without any limitations. Significant drawbacks remain the consideration of a smaller sample of patients in either group and short follow-up periods in these included studies. The use of different types of applications and conventional rehabilitation protocol also incorporates heterogeneity in this study. Even though the studies included are noted to be within the boundaries of publication bias, the heterogeneity of data and the lack of uniform PROM tools being used did not yield proper meta-analysis. However, strategically planning and subgroup analysis according to the follow-up periods with the inclusion of only high-quality RCTs has strengthened the overall quality of this review. Crawford et al. studied the rehabilitation process among total and partial KA, but to maintain uniformity in our study, only data on total KA has been analysed.

5. Conclusion

The present systematic review highlights comparable patient-reported outcome analysis at a short-term follow-up period among patients receiving mobile app-based rehabilitation over conventional rehabilitation after total knee replacements. However, the knee range of motion achieved after surgery is analysed to be better with traditional rehabilitation at the one-year end follow-up period.

Authors’ contribution

A.K·C - Planning of study, literature search, writing the manuscript, quality assessment of the included studies.

S.B. – Data management, outcome assessment, manuscript preparation, revising the manuscript.

A.J. - Literature search, writing the manuscript, quality assessment of the included studies.

B·S.R - Data management, outcome assessment, manuscript preparation.

B·B.N. – Literature search, writing the manuscript.

R.B·K - Planning of study, quality assessment of the included studies, writing and revising the manuscript.

Funding for the research

None.

Ethical review committee statement

Not applicable for this systematic review.

Consent to participation

Not applicable for this systematic review.

Declaration of competing interest

None among the authors are declared.

Contributor Information

Arghya Kundu Choudhury, Email: arghyakunduchoudhury@gmail.com.

Shivam Bansal, Email: Shivam.ban19@gmail.com.

Akash Jain, Email: Akawadia7777@gmail.com.

Balgovind S. Raja, Email: balgovindsraja@gmail.com.

Bishwa Bandhu Niraula, Email: bishwa8bangladesh@gmail.com.

Roop Bhushan Kalia, Email: roopkalia2003@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Kurtz S., Ong K., Lau E., Mowat F., Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Momoli A., Giaretta S., Modena M., Mario Micheloni G. The painful knee after total knee arthroplasty: evaluation and management. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(Suppl 2):60–67. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i2-S.6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wylde V., Beswick A., Bruce J., Blom A., Howells N., Gooberman-Hill R. Chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(8):461–470. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.180004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breugem S.J.M., Haverkamp D. Anterior knee pain after a total knee arthroplasty: what can cause this pain? World J Orthoped. 2014;5(3):163–170. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dávila Castrodad I.M., Recai T.M., Abraham M.M., et al. Rehabilitation protocols following total knee arthroplasty: a review of study designs and outcome measures. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(Suppl 7):S255. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.08.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens-Lapsley J.E., Balter J.E., Kohrt W.M., Eckhoff D.G. Quadriceps and hamstrings muscle dysfunction after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2460–2468. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen C., Lefèvre-Colau M.M., Poiraudeau S., Rannou F. Rehabilitation (exercise and strength training) and osteoarthritis: a critical narrative review. Ann. Phys. Rehab. Med. 2016;59(3):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fatoye F., Yeowell G., Wright J.M., Gebrye T. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions following total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141(10):1761–1778. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-03784-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raja B.S., Choudhury A.K., Paul S., Gowda A.K.S., Kalia R.B. No additional benefits of tissue adhesives for skin closure in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(1):186–202. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tripuraneni K.R., Foran J.R.H., Munson N.R., Racca N.E., Carothers J.T. A smartwatch paired with A mobile application provides postoperative self-directed rehabilitation without compromising total knee arthroplasty outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(12):3888–3893. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timmers T., Janssen L., van der Weegen W., et al. The effect of an app for day-to-day postoperative care education on patients with total knee replacement: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(10) doi: 10.2196/15323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardt S., Schulz M.R.G., Pfitzner T., et al. Improved early outcome after TKA through an app-based active muscle training programme-a randomized-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(11):3429–3437. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4918-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bäcker H.C., Wu C.H., Schulz M.R.G., Weber-Spickschen T.S., Perka C., Hardt S. App-based rehabilitation program after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141(9):1575–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-03789-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culliton S.E., Bryant D.M., MacDonald S.J., Hibbert K.M., Chesworth B.M. Effect of an e-learning tool on expectations and satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7):2153–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bini S.A., Mahajan J. Clinical outcomes of remote asynchronous telerehabilitation are equivalent to traditional therapy following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized control study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(2):239–247. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16634518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D., Park G., Kuo L.T., Park W. The effects of pain on quadriceps strength, joint proprioception and dynamic balance among women aged 65 to 75 years with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):245. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0932-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slemenda C., Brandt K.D., Heilman D.K., et al. Quadriceps weakness and osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(2):97–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petterson S.C., Barrance P., Buchanan T., Binder-Macleod S., Snyder-Mackler L. Mechanisms undlerlying quadriceps weakness in knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(3):422–427. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ef285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer C., Franz A., Harmsen J.F., et al. Soft-tissue damage during total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop. 2017;14(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langkilde A., Jakobsen T.L., Bandholm T.Q., et al. Inflammation and post-operative recovery in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty-secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(8):1265–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shukla H., Nair S.R., Thakker D. Role of telerehabilitation in patients following total knee arthroplasty: evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(2):339–346. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16628996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauwens P.H., Fayard J.M., Tatar M., et al. Evaluation of a smartphone application for self-rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction during a COVID-19 lockdown. J Orthop Traumatol: Surg. & Res. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2022.103342. Published online June 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGinn T.L., Etcheson J.I., Gwam C.U., et al. Short-term outcomes for total knee arthroplasty patients with active extension lag. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(11):204. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.05.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiavone Panni A., Cerciello S., Vasso M., Tartarone M. Stiffness in total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(3):111–118. doi: 10.1007/s10195-009-0054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goudie S.T., Deakin A.H., Ahmad A., Maheshwari R., Picard F. Flexion contracture following primary total knee arthroplasty: risk factors and outcomes. Orthopedics. 2011;34(12):e855–e859. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20111021-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez-Merchán E.C. The stiff total knee arthroplasty: causes, treatment modalities and results. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4(10):602–610. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Djian P., Christel P., Witvoet J. [Arthroscopic release for knee joint stiffness after total knee arthroplasty] Rev. Chir. Orthop. Reparatrice Appar. Mot. 2002;88(2):163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleischman A.N., Crizer M.P., Tarabichi M., et al. Insall award: recovery of knee flexion with unsupervised home exercise is not inferior to outpatient physical therapy after TKA: a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;477(1):60–69. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000561. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W.L., Rondon A.J., Tan T.L., Wilsman J., Purtill J.J. Self-directed home exercises vs outpatient physical therapy after total knee arthroplasty: value and outcomes following a protocol change. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(10):2388–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fillingham Y.A., Ramkumar D.B., Jevsevar D.S., et al. Tranexamic acid use in total joint arthroplasty: the clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the American association of hip and knee surgeons, American society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine, American academy of orthopaedic surgeons, hip society, and knee society. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3065–3069. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik I.V., Devasenapathy N., Kumar A., et al. Estimation of expenditure and challenges related to rehabilitation after knee arthroplasty: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55(5):1317–1325. doi: 10.1007/s43465-021-00405-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung A., Li Y., Keefe F.J., et al. Ninety-day and one-year healthcare utilization and costs after knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(10):1462–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yayac M., Moltz R., Pivec R., Lonner J.H., Courtney P.M., Austin M.S. Formal physical therapy following total hip and knee arthroplasty incurs additional cost without improving outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(10):2779–2785. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tousignant M., Moffet H., Nadeau S., et al. Cost analysis of in-home telerehabilitation for post-knee arthroplasty. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]