Abstract

Background/Aim

Atezolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expressed on cancer cells derived from various organs and antigen-presenting cells and is currently commonly used in combination with chemotherapy. We conducted a study to clarify the current status of response to atezolizumab monotherapy in clinical practice and clarify the factors that contribute to long-term response and survival.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with atezolizumab monotherapy from April 2018 to March 2023 at 11 Hospitals.

Results

The 147 patients evaluated had a progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.0 months and an overall survival of 7.0 months. Immune-related adverse events of any grade were observed in 13 patients (8.8%), grade 3 or higher in nine patients (6.1%), and grade 5 with pulmonary toxicity in one patient (0.7%). Favorable factors related to PFS were ‘types of NSCLC other than adenocarcinoma’. Favorable factors for overall survival were ‘performance status 0-1’ and ‘treatment lines up to 3’. There were 16 patients (10.9%) with PFS >1 year. No characteristic clinical findings were found in these 16 patients compared to the remaining 131 patients.

Conclusion

Efficacy and immune-related adverse events of NSCLC patients associated with atezolizumab monotherapy were comparable to those of previous clinical trial results. Knowledge of characteristics of patients who are most likely to benefit from atezolizumab monotherapy is a crucial step towards implementing appropriate prescribing.

Keywords: Atezolizumab, chemotherapy, progression-free survival, overall survival, immune-related adverse events

Programmed death-1 (PD-1) is expressed on activated T cells (1,2). By binding PD-L1 and PD-L2 expressed on cancer cells and antigen-presenting cells, this PD-L1 suppresses T cell activation, resulting in immune escape of cancer cells (1,2). Anti-PD-1 antibodies bind to PD-1 on T cells and block the binding of PD-1 to PD-L1/PD-L2, thereby blocking the transmission of inhibitory signals and activating T cells, and restoring the antitumor effect (1,2). On the other hand, anti-PD-L1 antibodies block the interaction with PD-1 on T cells by binding to PD-L1 expressed by cancer cells and antigen-presenting cells (1,2). As a result, inhibitory signaling to T cells is reduced and T cell activation is maintained (1,2).

Atezolizumab is an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody that targets PD-L1 expressed on cancer cells and antigen-presenting cells and inhibits its interaction with PD-1 on T cells, thus exerting its anti-tumor effect (3). PD-L1 expression has been observed in carcinomas arising from many organs, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (3). For NSCLC, atezolizumab was shown to be useful in the OAK and IMpower110 trials (3,4). Atezolizumab, like other anti-PD-1 antibodies, was initially used as a monotherapy, but has become popular in combination with chemotherapy (5,6). Real-world clinical data for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) monotherapy for NSCLC have been reported from several institutes (7-18). However, most were reports on anti-PD-1 antibodies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab (8-11,17,18). Although there have been studies on ICI monotherapy, including atezolizumab (7,12-16), detailed clinical outcomes for patients treated with atezolizumab monotherapy have been limited (7,12,16). To the best of our knowledge, there have been only two reports on clinical outcomes for atezolizumab monotherapy, both with cohorts of less than 50 patients (12,16).

ICI monotherapy might be prescribed as a third line of therapy or later, or as ICI re-challenge therapy in patients who have already received ICI combination chemotherapy. Although it seems difficult to expect a response, the clinical significance of this therapy is unclear. The aim of the study was to clarify the significance of atezolizumab monotherapy in clinical practice and to clarify the factors that contribute to long-term response and survival. We believe that this information will provide useful information for future treatment with atezolizumab.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study reviewed patients with pathologically-diagnosed NSCLC from April 2018 to March 2023 at 11 Hospitals in our prefecture (Ibaraki Prefecture: 6,095 km2). Among these patients, information from all patients who received atezolizumab monotherapy were assembled with no exclusion criteria. Pathologic diagnosis of NSCLC was determined according to the WHO classification. Prior to initiation of atezolizumab treatment, all patients underwent TNM classification (19). For imaging, head computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, bone scans, and ultrasonography and/or computed tomography of the abdomen were performed. Suitable patients were identified in each hospital’s clinical database, and information on patient demographics [age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS), histology, clinical stage, etc.] was extracted from databases. Tumor response was assessed as complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease, or not evaluable according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (20). Information was also extracted on response to treatment, duration of response and survival from initiation of atezolizumab. Adverse events were classified using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0) (21).

For statistical comparison between the two groups, the Chi-squared test and Mann-Whitney U-test were used. Survival probability was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and evaluated using the log-rank test and Cox’s proportional hazard model. Multivariate analysis was performed using factors that had p<0.02 by univariate analysis. A p-value of <0.01 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Tsukuba Mito Medical Center, Mito Kyodo General Hospital (NO-22-42) and each participating hospital.

Results

Patient characteristics. Clinical information on all the 147 patients who received atezolizumab monotherapy during the study period was compiled. Table I shows patient characteristics. Median age was 68 years (range=43-87 years) and 109 (74.1%) were men; 103 patients (70.1%) had PS 0-1 and 105 patients (71.4%) had adenocarcinoma. The median ‘treatment line’ for atezolizumab therapy was third-line of therapy (range=1-10 lines). Seventy-four patients (50.3%) received first- to third-line therapy, and 73 patients (49.7%) had atezolizumab therapy in the fourth or later lines. Six patients (4.1%) received atezolizumab as first-line therapy.

Table I. Clinical features of NSCLC patients treated with atezolizumab monotherapy.

NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer; EGFR: epidermal grwoth factor receptor; ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

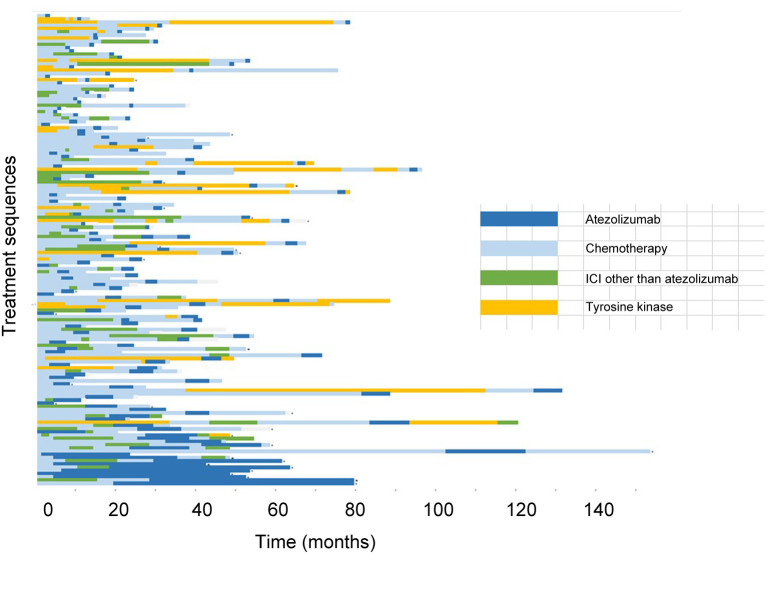

Response to treatment. Figure 1 shows the specific treatment sequences for the 147 patients. The response rate of atezolizumab monotherapy was 15.0% (three complete response, 19 partial response). Thirty-five patients (23.8%) were observed to have stable disease, giving a disease control rate of 38.8%. There was no significant difference in response rate among sex (men, 9.2% vs. women, 7.9%; p=0.1936), PS (PS 0-1, 18.4% vs. PS 2-3, 6.8%; p=0.0810), or atezolizumab treatment line (lines 1-3, 18.9% vs. line 4 or later, 11.0%; p=0.2476). However, compared to patients with adenocarcinoma, patients with non-adenocarcinoma histology had a higher response rate (28.6% vs. 9.5%; p=0.001).

Figure 1. Treatment sequences for the 147 patients with non-small cell lung cancer who were treated with atezolizumab monotherapy.

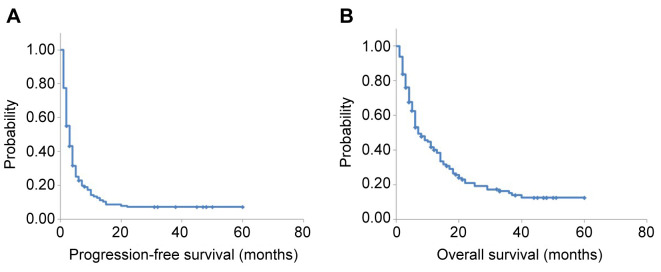

Survival analysis. Of the 147 patients evaluated, 114 (77.6%) had died at the time of analysis. The median follow-up time was 6.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI)=10.0-14.0 months] (Figure 2). One- and two-year overall survival (OS) was 34.7% (95% CI=26.9%-42.5%) and 15.0% (95% CI=9.1%-20.8%), respectively. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.0 months (95% CI=2.3-3.7 months) and median OS was 7.0 months (95% CI=4.7-9.3 months).

Figure 2. In the 147 patients who were treated with atezolizumab monotherapy, median progression-free survival was 3.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI)=2.3-3.7 months] (A) and median overall survival was 7.0 months (95% CI=4.7-9.3 months) (B).

In order to identify favorable factors affecting PFS and OS, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using sex, PS, age, PD-L1, stage, NSCLC histology, driver genes, irAEs, and treatment line as variables. As shown in Table II, ‘types of NSCLC other than adenocarcinoma’ was a favorable prognostic factor in multivariate analysis for PFS. In multivariate analysis for OS, both ‘good PS (0-1)’ and ‘treatment line up to third-line’ were favorable prognostic factors for OS (Table II).

Table II. Uni- and multivariate analysis of survival from the initiation of atezolizumab monotherapy.

PD-L1: Programmed cell death ligand 1; AD: adenocarcinoma; irAE: immune-related adverse events; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitors; CI: confidence interval.

Sixteen patients (10.9%) had PFS >1 year. Comparing these 16 patients with 131 patients who had PFS <1 year, no characteristic clinical differences were found (Table III).

Table III. Comparison of clinical features in patients who had progression-free survival more than one year (Group A) and those who did not have (Groups B).

PS: Performance status; PD-L1: programmed cell death ligand 1; irAE: immune-related adverse events.

Toxicity. Table IV shows immune-related adverse events (irAEs). irAEs were observed in 13 cases (8.8%), of which grade 3 or higher was observed in nine cases (6.1%). Pulmonary toxicity was observed in three patients, two of whom were grade 3 and one was grade 5. Other irAEs included hepatobiliary toxicity in three patients (one grade 1, one grade 2, one grade 4), two with thyroid dysfunction (two grade 2), and one with pituitary dysfunction. There was also one case of pneumothorax (grade 2), one case of hemoptysis, one case of hyperglycemia (grade 3), and one case of arthralgia (grade 3).

Table IV. Immune-related adverse events.

Discussion

The 147 patients evaluated had a PFS of 3.0 months and an OS of 7.0 months. IrAEs were observed in 13 patients (8.8%), with grade 3 or higher in nine patients (6.1%), and grade 5 with pulmonary toxicity in one patient (0.7%). Favorable factors related to PFS were ‘types of NSCLC other than adenocarcinoma’. Favorable factors for OS were ‘PS 0-1’ and ‘treatment line up to 3’. There were 16 patients (10.9%) with PFS >1 year. No characteristic clinical findings were found in these 16 patients compared to the remaining 131 patients.

Anti-PD-1 antibodies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, suppress immune checkpoints by binding to PD-1 on T cells, a type of immune cell (1,2). On the other hand, the PD-L1 antibody, atezolizumab, suppresses immune checkpoints by binding to PD-L1 on cancer cells and antigen-presenting cells (1,2). Anti-PD-1 antibodies are known to bind to PD-L1 and PD-L2, and anti-PD-L1 antibodies are known to bind to PD-1 and B7-1. This means that the inhibitory binding is slightly different: anti-PD-1 antibodies can, therefore, block both PD-1/PD-L1 binding and PD-1/PD-L2 binding (1,2). However, PD-L1 antibodies block PD-1/PD-L1 binding, but not PD-1/PD-L2 binding. Alternatively, PD-L1 antibodies can block B7-1/PD-L1 binding (1,2). It has been speculated that this difference might affect clinical outcomes, as well as differences in efficacy and irAEs (3). Although it is generally accepted that there might be little difference in the efficacy and irAEs between anti-PD-1 and anti-PL-L1 antibodies, information regarding atezolizumab monotherapy for NSCLC in clinical practice is insufficient.

In clinical trials of ICI monotherapy for NSCLC in patients on second and subsequent lines of therapy, PFS and OS for anti-PD-1 antibodies are reported to be 2-7 months and 5.8-18 months, respectively (12). A clinical trial of single-agent PD-L1 antibody for NSCLC patients (OAK trial) reported a PFS of 2.8 months and an OS of 12.7 months (3). This trial did not include patients with poor PS and was limited to patients receiving atezolizumab on treatment lines 2-3. Although some reports included pembrolizumab, most of the clinical results of ICI monotherapy for NSCLC patients were for nivolumab monotherapy. The PFS and OS were 1.8-3.3 months and 5.9-14.6 months, respectively (10).

There are only two reports of PFS and OS with atezolizumab monotherapy in clinical practice. In them, PFS and OS were 1.4 to 2.0 months and 6.5 to 12.8 months, respectively (11,16). However, the number of patients investigated in these two studies was 38 and 43, respectively, and they were not fully evaluated (11,16). The PFS of the present study was similar to those of clinical trials of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies in clinical practice. The median age of patients in this study was 68 years, and poor PS was 29.9%, resulting in an OS of 7.0 months. These results were similar to those of Weis et al. who administered atezolizumab to 43 second-line patients (PFS, 2.0 months; OS, 6.5 months) (16). The median age of their patients was 67.2 years, and 20.7% of the cohort had poor PS.

Several studies have performed multivariate analyses on prognostic factors in ICI monotherapy. Most were studies on anti-PD-1 antibodies, and adverse factors cited included poor PS, low PD-L1, epidermal growth factor receptor positivity, tumor size, increased platelets, and bone metastasis (7-9). Only the report by Furuya et al. evaluated prognostic factors for an anti-PD-L1 antibody. They reported that ‘good PS’ was a favorable factor for both PFS and OS in 38 patients who received atezolizumab monotherapy after anti-PD-1 antibodies (11). Good PS was also a favorable factor in OS in our study. However, if patient characteristics and treatment sequence and other clinical conditions are different, different results might be obtained. As such, caution is required and additional data in this area is needed. To our knowledge, long-term treatment with atezolizumab monotherapy has not been defined, and there have been no reports of patients receiving long-term treatment. Furuya et al. reported that seven of 38 patients were able to receive atezolizumab monotherapy for at least 4.0 months (11). Among our patients, 16 (10.9%) had >1 year of atezolizumab monotherapy. Although favorable clinical factors could not be identified, it is noteworthy that there were clearly individual patients who maintained a long-term response.

A total of 60.5% of patients in the OAK trial had irAEs of any grade (3). In clinical trials of single-agent ICI therapy, Sonpavde et al. investigated the irAEs that developed in the 8,730 patients in the trials (22). Their review showed a lower frequency of irAEs with the anti-PD-1 antibody, atezolizumab, than those with anti-PD-L1 antibodies. They speculated that these results were due to differences in the way anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 antibodies acted (1,2). On the other hand, Mencoboni et al. reviewed atezolizumab monotherapy irAEs in clinical practice. In their review, most patients were treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, and they reported an incidence of irAEs of any grade of 7%-71%, and of grades 3-4 of 0-25% (12). Patients with grade 5 lung injury were also reported (23). In our study, irAEs of any grade were observed in only 8.8% of patients, of which grade 3 or higher was observed in 6.1%. One patient developed grade 5 pulmonary toxicity. Although the incidence of irAEs of any grade appeared to be very low, the possibility of under-evaluation in retrospective studies cannot be ruled out.

There are other limitations in this study that should be mentioned. Although the study included the largest number of patients reported for such a study, it was a retrospective study of patients with a wide range of background characteristics. It should be noted that our results are not definitive and do not allow final conclusions. Novel driver gene examinations such as Kristen rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), c-ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) and rearranged during transfection (RET) were introduced into clinical practice during the study period. Identification of these driver genes as well as EGFR and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and progress of corresponding therapeutic agents have extended life and provided palliation for lung cancer-patients positive for these mutations (24). As shown in Table I, this study included 8 patients positive for driver genes other than EGFR [4 KRAS positive, 3 ALK fusion gene-positive, 1 B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) positive]. Those genes could not be evaluated equally in all patients. Therefore, it was possible that this situation affected the results. Because of the small number of these patients and because it was impossible to newly investigate the driver genes that were undetectable at the beginning of this study, we treated them as EGFR gene-negative patients in this study. It might have been better to investigate the prognosis separately for driver gene-positive and -negative patients for these driver genes. Since there was a high proportion of epidermal growth factor receptor gene-positive patients, it might be possible to analyze this cohort separately from this report.

The results of this study indicate that real-world atezolizumab monotherapy in patients with unfavorable clinical conditions, might achieve PFS and OS similar to those reported in previous clinical trials. The frequency and severity of irAEs were similar to those of previous reports in trials and practice with ICI monotherapy, confirming the existence of cases in which long-term administration is possible. Although ICI has entered the era of combination therapy with chemotherapy, the selection and appropriate management of patients who can benefit from atezolizumab monotherapy is still important. Efforts to identify patients who could benefit from atezolizumab monotherapy will continue to be of value.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

SO, KM, TS, SH, HSaku, and HS designed the study. TN, HY, TS, YW, SO, TT, NK, KM, SH, HirofS, TY, KK, MI, HS, HI, TK, TE, and TS collected the data. SH, SO, RN and HS analyzed the data. SH, SO, HS, and NH prepared the manuscript. AN, HS, and NH supervised the study. All Authors approved the final version for submission.

References

- 1.Khadela A, Postwala H, Rana D, Dave H, Ranch K, Boddu SHS. A review of recent advances in the novel therapeutic targets and immunotherapy for lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2023;40(5):152. doi: 10.1007/s12032-023-02005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahiri A, Maji A, Potdar PD, Singh N, Parikh P, Bisht B, Mukherjee A, Paul MK. Lung cancer immunotherapy: progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01740-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandara DR, Von Pawel J, Mazieres J, Sullivan R, Helland Å, Han J, Ponce Aix S, Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Kubo T, Park K, Goldschmidt J, Gandhi M, Yun C, Yu W, Matheny C, He P, Sandler A, Ballinger M, Fehrenbacher L. Atezolizumab treatment beyond progression in advanced NSCLC: Results from the randomized, phase III OAK study. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(12):1906–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, De Marinis F, Reinmuth N, Vergnenegre A, Barrios CH, Morise M, Felip E, Andric Z, Geater S, Özgüroğlu M, Zou W, Sandler A, Enquist I, Komatsubara K, Deng Y, Kuriki H, Wen X, Mccleland M, Mocci S, Jassem J, Spigel DR. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1–Selected Patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1328–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryu R, Ward KE. Atezolizumab for the first-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Current status and future prospects. Front Oncol. 2018;8:277. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boussageon M, Swalduz A, Chouaïd C, Bylicki O. First-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with immune-checkpoint inhibitors: New combinations and long-term data. BioDrugs. 2022;36(2):137–151. doi: 10.1007/s40259-022-00515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knetki-Wróblewska M, Tabor S, Piórek A, Płużański A, Winiarczyk K, Zaborowska-Szmit M, Zajda K, Kowalski DM, Krzakowski M. Nivolumab or atezolizumab in the second-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer? A prognostic index based on data from daily practice. J Clin Med. 2023;12(6) doi: 10.3390/jcm12062409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juarez-Garcia A, Sharma R, Hunger M, Kayaniyil S, Penrod JR, Chouaïd C. Real-world effectiveness of immunotherapies in pre-treated, advanced non-small cell lung cancer Patients: A systematic literature review. Lung Cancer. 2022;166:205–220. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi MG, Choi CM, Lee DH, Kim SW, Yoon S, Ji W, Lee JC. Impact of gender on response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing second- or later-line treatment. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022;11(9):1866–1876. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-22-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanović M, Knez L, Herzog A, Kovačević M, Cufer T. Immunotherapy for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: real-world data from an academic central and eastern european center. Oncologist. 2021;26(12):e2143–e2150. doi: 10.1002/onco.13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuya N, Nishino M, Wakuda K, Ikeda S, Sato T, Ushio R, Tanzawa S, Sata M, Ito K. Real-world efficacy of atezolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter cohort study focused on performance status and retreatment after failure of anti-PD-1 antibody. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12(5):613–618. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mencoboni M, Ceppi M, Bruzzone M, Taveggia P, Cavo A, Scordamaglia F, Gualco M, Filiberti RA. Effectiveness and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced non small-cell lung cancer in real-world: Review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(6):1388. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayers KL, Mullaney T, Zhou X, Liu JJ, Lee K, Ma M, Jones S, Li L, Redfern A, Jappe W, Liu Z, Goldsweig H, Yadav KK, Hahner N, Dietz M, Zimmerman M, Prentice T, Newman S, Veluswamy R, Wisnivesky J, Hirsch FR, Oh WK, Li SD, Schadt EE, Chen R. Analysis of real-world data to investigate the impact of race and ethnicity on response to programmed cell death-1 and programmed cell death-ligand 1 inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancers. Oncologist. 2021;26(7):e1226–e1239. doi: 10.1002/onco.13780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger-gritsch S, Olschewski H, Kocher F, Wurm R, Absenger G, Flicker M, Hermann A, Heininger P, Fiegl M, Zechmeister M, Endel F, Wild C, Pall G. Real-world experience with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(21-22):1122–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01940-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stinchcombe TE, Miksad RA, Gossai A, Griffith SD, Torres AZ. Real-world outcomes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor beyond progression. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21(5):389–394.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weis TM, Hough S, Reddy HG, Daignault-Newton S, Kalemkerian GP. Real-world comparison of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer following platinum-based chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(3):564–571. doi: 10.1177/1078155219855127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morita R, Okishio K, Shimizu J, Saito H, Sakai H, Kim YH, Hataji O, Yomota M, Nishio M, Aoe K, Kanai O, Kumagai T, Kibata K, Tsukamoto H, Oizumi S, Fujimoto D, Tanaka H, Mizuno K, Masuda T, Kozuki T, Haku T, Suzuki H, Okamoto I, Hoshiyama H, Ueda J, Ohe Y. Real-world effectiveness and safety of nivolumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter retrospective observational study in Japan. Lung Cancer. 2020;140:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlesi F, Dixmier A, Debieuvre D, Raspaud C, Auliac JB, Benoit N, Bombaron P, Moro-Sibilot D, Audigier-Valette C, Asselain B, Egenod T, Rabeau A, Fayette J, Sanchez ML, Labourey JL, Westeel V, Lamoureux P, Cotte FE, Allan V, Daumont M, Dumanoir J, Reynaud D, Calvet CY, Ozan N, Pérol M. Effectiveness and safety of nivolumab in the treatment of lung cancer patients in France: preliminary results from the real-world EVIDENS study. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1744898. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1744898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P, Mitchell A, Bolejack V, Goldstraw P, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Ball D, Beer DG, Beyruti R, Bolejack V, Chansky K, Crowley J, Detterbeck F, Erich Eberhardt WE, Edwards J, Galateau-Sallé F, Giroux D, Gleeson F, Groome P, Huang J, Kennedy C, Kim J, Kim YT, Kingsbury L, Kondo H, Krasnik M, Kubota K, Lerut A, Lyons G, Marino M, Marom EM, Van Meerbeeck J, Mitchell A, Nakano T, Nicholson AG, Nowak A, Peake M, Rice T, Rosenzweig K, Ruffini E, Rusch V, Saijo N, Van Schil P, Sculier J, Shemanski L, Stratton K, Suzuki K, Tachimori Y, Thomas CF, Travis W, Tsao MS, Turrisi A, Vansteenkiste J, Watanabe H, Wu Y, Baas P, Erasmus J, Hasegawa S, Inai K, Kernstine K, Kindler H, Krug L, Nackaerts K, Pass H, Rice D, Falkson C, Filosso PL, Giaccone G, Kondo K, Lucchi M, Okumura M, Blackstone E, Abad Cavaco F, Ansótegui Barrera E, Abal Arca J, Parente Lamelas I, Arnau Obrer A, Guijarro Jorge R, Ball D, Bascom G, Blanco Orozco A, González Castro M, Blum M, Chimondeguy D, Cvijanovic V, Defranchi S, De Olaiz Navarro B, Escobar Campuzano I, Macía Vidueira I, Fernández Araujo E, Andreo García F, Fong K, Francisco Corral G, Cerezo González S, Freixinet Gilart J, García Arangüena L, García Barajas S, Girard P, Goksel T, González Budiño M, González Casaurrán G, Gullón Blanco J, Hernández Hernández J, Hernández Rodríguez H, Herrero Collantes J, Iglesias Heras M, Izquierdo Elena J, Jakobsen E, Kostas S, León Atance P, Núñez Ares A, Liao M, Losanovscky M, Lyons G, Magaroles R, De Esteban Júlvez L, Mariñán Gorospe M, Mccaughan B, Kennedy C, Melchor Íñiguez R, Miravet Sorribes L, Naranjo Gozalo S, Álvarez De Arriba C, Núñez Delgado M, Padilla Alarcón J, Peñalver Cuesta J, Park J, Pass H, Pavón Fernández M, Rosenberg M, Ruffini E, Rusch V, Sánchez De Cos Escuín J, Saura Vinuesa A, Serra Mitjans M, Strand T, Subotic D, Swisher S, Terra R, Thomas C, Tournoy K, Van Schil P, Velasquez M, Wu Y, Yokoi K. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals forRevision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer E, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz L, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) 1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0) Available at: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fctep.cancer.gov%2FprotocolDevelopment%2Felectronic_applications%2Fdocs%2FCTCAE_v5.0.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK. [Last accessed on February 16, 2023]

- 22.Spagnolo P, Chaudhuri N, Bernardinello N, Karampitsakos T, Sampsonas F, Tzouvelekis A. Pulmonary adverse events following immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2022;28(5):391–398. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonpavde GP, Grivas P, Lin Y, Hennessy D, Hunt JD. Immune-related adverse events with PD-1 versus PD-L1 inhibitors: a meta-analysis of 8730 patients from clinical trials. Future Oncol. 2021;17(19):2545–2558. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Check JH, Poretta T, Check D, Srivastava M. Lung cancer – standard therapy and the use of a novel, highly effective, well tolerated, treatment with progesterone receptor modulators. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(3):951–965. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]