Abstract

The present study employed a dyadic data analysis approach to examine the association between partners’ dispositional empathy and IPV. Data were collected from 1,156 couples, who were participants in Wave 3 of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). For both IPV perpetration and IPV victimization, significant actor effects for men and significant partner effects for men to women emerged: Men who were less empathic were more likely to perpetrate IPV and to be victimized. Similarly, women whose male partners were less empathic were more likely to perpetrate IPV and to be victimized. Findings partially generalized to analyzes assessing the associations between empathy and the different types of IPV (psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and occurrence of injury from IPV) separately. The present findings show that men’s levels of empathy may carry more weight in determining their own as well as their partners’ aggressive behaviors than do women’s levels of empathy.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, dyadic, couples, compassion, young adults

Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as the physical, psychological, and/or sexual abuse of an intimate partner (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012), is a prevalent concern for young couples in the United States. Research indicates that rates of IPV are high; an estimated 27.5% of men and 31.5% of women have experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime (CDC, 2011). In addition, IPV has been tied to a variety of negative consequences, ranging from increased stress (e.g., Testa & Leonard, 2001) to severe depression (e.g., Peltzer, Pengpid, McFarlane, & Banyini, 2013). Thus, it is important to identify and better understand potential risk factors of IPV, with the ultimate goal of using this knowledge to target men and women at risk and teaching them skills that may potentially decrease their likelihood of experiencing IPV at some point in their lifetime. A deficit in empathy, defined as one’s ability to understand and share in another person’s emotional experience (Cohen & Strayer, 1996), has been found to be associated with individuals’ general tendencies to exhibit aggressive and antisocial behaviors (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004; Miller & Eisenberg, 1988; Richardson, Hammock, Smith, Gardner, & Signo, 1994). In addition, some studies have identified an association between empathy and the use of aggressive strategies towards an intimate partner (e.g., Covell, Huss, & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2007). However, the inter-relatedness of the effects that individuals’ empathy may have on their own levels of IPV (actor effects) as well as on their partner’s levels of IPV (partner effects; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) remains largely understudied. Thus, the aim of the present study was to employ a dyadic data analysis approach to examine the association between partners’ overall levels of empathy and IPV perpetration and victimization.

Several decades of research have provided support for the assumption that empathy encourages pro-social or altruistic behavior (e.g., Batson, Fultz, & Schoenrade, 1987). Likewise, empathic reactions have been found to play an important role in inhibiting aggressive or antisocial actions towards others (Miller & Eisenberg, 1988). For example, Richardson and colleagues (1994), in a series of three studies, examined the role of empathy as a cognitive inhibitor of interpersonal aggression. The authors found that dispositional empathy correlated negatively with self-reported aggression and with conflict responses that reflected little concern for the needs of others. These findings are supported by the results of two meta-analyses showing that low dispositional empathy was related to externalizing, aggressive, and antisocial behavior in older children, adolescents, and adults (Miller & Eisenberg, 1988) as well as offenders (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004).

As these meta-analyses show, the evidence for an association between low empathy and general aggression is strong. However, only few studies have examined whether these effects of empathy generalize to the specific context of aggression in intimate relationships. Covell et al. (2007) explored the associations between multiple dimensions of empathy and the frequency of perpetrating different types of domestic violence in a sample of 104 men who were participating in a domestic violence offenders’ program. The different dimensions of empathy both singularly and in combination related to the different types of IPV: Lower levels of perspective taking abilities were related to overall and psychological IPV. Higher levels of discomfort in reaction to other people’s emotions were related to overall and physical IPV. Furthermore, Christopher, Owens, & Stecker (1993) developed a Structural Equation Model (SEM) to predict men’s premarital sexual aggression towards an intimate partner. Low empathy emerged as one of the significant predictors of sexual IPV. A major limitation of this previous research is the researchers’ focus on only male perpetrators of IPV. This limitation was addressed in research by Peloquin, Lafontaine, & Brassard (2011), who examined the association between empathy and IPV not only among men but also among women. In their study, 193 community couples provided information on their attachment tendencies, empathy, and psychological aggression. Concordant with the authors’ predictions, dyadic empathy was found to be negatively associated with use of psychological partner aggression perpetrated by men and by women. However, whereas individuals’ empathy was associated with their own levels of psychological aggression (actor effects), it was not associated with their partners’ levels of psychological aggression (partner effects). The authors reason that individuals’ ability to understand each other’s point of view and to feel compassion for each other’s distress and misfortune might decrease the likelihood of them using psychological aggression against their partner. Since individuals’ levels of empathy were not found to be related to their partners’ use of psychological aggression, Peloquin et al. (2011) propose that whether an individual feels understood and emotionally validated by one’s partner may bear a stronger relationship with one’s aggressive behavior than the level of empathy one’s partner reports. Thus, men’s and women’s dyadic functioning may be more strongly related to their own emotions, thoughts, and behaviors than that of their partners. Although Peloquin et al.’s (2011) study clearly extends the research by Covell et al. (2007) and Christopher et al. (1993), this study also bears some limitations: Unfortunately, the authors focused solely on psychological IPV and it remains uncertain whether their findings would generalize to other types of IPV, such as physical and sexual IPV, as well as overall levels of partner aggression (i.e., a combination of the different types of IPV). Furthermore, Peloquin et al.’s sample was relatively small and thus, findings warrant replication in a much larger, nationally representative sample.

A concept similar to dispositional empathy, empathic accuracy, has also been found to relate to IPV in a limited number of studies. Empathic accuracy describes dyad members’ ability to read and understand their partners’ affective and cognitive state accurately (Clements, Holtzworth-Munroe, Schweinle, & Ickes, 2000). In a study of 71 heterosexual couples in committed relationships, Clements et al. (2000) tested the notion that, relative to non-violent partners, physically violent partners would be poor interpreters of one another’s thoughts and feelings. Results showed that violent men were significantly less accurate at inferring their female partner’s thoughts and feelings than were non-violent, non-distressed men. On the other hand, violent women did not exhibit the same empathic accuracy difficulty as their male partners did. Thus, the authors conclude that men’s IPV perpetration may be due to a lack of empathic accuracy whereas women’s IPV perpetration may not be related to empathic accuracy. In another study using the empathic accuracy paradigm (N = 86 male individuals), Schweinle, Ickes, and Bernstein (2002) found that the greater husbands’ bias to over-attribute criticism and rejection to the thoughts and feelings of women they had never met, the more husbands reported behaving in a verbally aggressive way toward their own wives. The authors reason that maritally aggressive men may not be uniquely provoked by their own female partners, but may rather be biased to over-attribute criticism and rejection to women in general. These two studies employing the empathic accuracy paradigm clearly shed additional light on the association between empathy and IPV. However, it is important to keep in mind that, although related, overall levels of empathy and empathic accuracy represent two separate constructs. Thus, we do not know whether findings based on the empathic accuracy design would generalize to studies employing a measure of overall empathy instead of empathic accuracy. Furthermore, as highlighted in the discussion of Peloquin et al.’s (2011) findings, it is important to replicate these findings in larger samples. Schweinle et al.’s (2002) sample was comprised of only 86 individuals (as opposed to couples). Even though Clements et al.’s (2000) sample was composed of couples, their sample also was relatively small (N = 71 couples).

The studies described above indicate that a lack of empathy and empathic accuracy appear to be linked to aggressive behavior. Most of these studies examined this association among male perpetrators only. Although Peloquin et al. (2011) did assess both men’s and women’s empathy in relation to their own and their partners’ IPV, the authors exclusively focused on psychological IPV in their study. Thus, it remains unclear whether Peloquin et al.’s (2011) findings that the association between empathy and IPV is expressed for both men and women, however solely in actor effects and not partner effects, would generalize to other types of IPV and overall levels of IPV, not only including psychological but also physical and sexual IPV. To the extent that overall levels of empathy are related to levels of empathic accuracy, it is likely that actor and partner effect findings may differ when considering overall IPV, because the association between empathic accuracy and physical and verbal and IPV has only been found for men (Clements et al., 2000; Schweinle et al., 2002). In addition, the samples utilized in previous research to explore the association between empathy and IPV were relatively small and thus warrant replication in a larger and nationally representative sample of couples.

To address these remaining research questions, the present study set out to examine the association between men’s and women’s dispositional empathy and their overall levels of IPV perpetration and victimization in a large, nationally representative sample (N = 1,156 couples). Because is important to examine potential social skill deficits among both partners in physically violent relationships, as couple interactions are dynamic processes in which both partners influence one another (Clements et al., 2000), the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM, Kenny et al., 2006) was used. By statistically accounting for non-independence and the effects that a partner has on an individual’s outcome, the APIM allows to estimate both actor and partner effects. We predicted that individuals’ low dispositional empathy would be associated with their own and their partner’s increased use of IPV. These predictions were based on the assumption that individuals’ low empathy may lead them to over-attribute criticism and rejection to the thoughts and feelings of their partners and may thus result in increased IPV (Schweinle et al., 2002). At the same time, individuals’ low empathy may translate into their partners feeling misunderstood or invalidated, which may increase the likelihood that their partners will use aggression out of frustration or discontentment (Peloquin et al., 2011). However, due to previous studies showing that only men’s empathic accuracy and IPV were related, we further predicted that only men’s dispositional empathy would be associated with their own and their female partners’ levels of IPV perpetration and victimization, whereas we predicted that there would be no association between women’s dispositional empathy and either their own or their partners’ IPV.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The present study used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health began in 1995 and assessed health-related behaviors among adolescents and their outcomes during young adulthood (see Harris et al., 2009, for study design). In the original Add Health study, individuals completed in-home interviews at four separate time points (called “waves”). In the present study, analyses were conducted using the Romantic Pairs subsample from Wave 3 (collected in 2001-2002). The full Wave 3 data set contains 15,170 participants. From this wave, 1,507 respondents were pre-selected to participate in the Romantic Pairs subsample, meaning that their current romantic partners were invited to participate in the study. In order to be eligible for the Add Health Romantic Pairs subsample, couples had to be heterosexual, in a current relationship, at least 18 years of age, and be listed as one of the most important relationships.

In Wave 3 of Add Health, participants were given the opportunity to provide information on as many (current and past) romantic relationships as they desired to list. To facilitate matching of dyadic partners and to ensure that partners reported information about one another, the final sample used for analysis in the present study (N = 1,156 couples) included only those couples from the Romantic Pairs subsample, in which both partners indicated that they were involved in only one current relationship at the time of study conduction. In the present sample, men ranged in age from 18 to 43 years of age (M = 23.48, SD = 3.28) and women ranged in age from 18 to 40 years of age (M = 21.91, SD = 2.44). About three-quarters of couples indicated they were cohabitating at the time of data collection, about half of these couples indicated they were also married.

Materials

Empathy.

Empathy was assessed using four items taken from the Bem Sex Role Inventory instrument (Bem, 1974), which asked participants to indicate how often each of the statements provided was true of them. This measure of empathy has been utilized in previous research using the Add Health Wave 3 sample (Galinski & Sonenstein, 2011), in which it has been found to be a valid measure of empathy (α = .86). Items were: “I am sympathetic,” “I am sensitive to the needs of others,” “I am understanding,” and “I am compassionate.” Thus, the current measure assessed participants’ subjective self-evaluations of how empathic they perceived themselves. All items were rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (never or almost never true) to 7 (always or almost always true). Men and women’s empathy scores were used as the antecedents in the present study.

Intimate partner violence.

IPV was measured using a revised version of the Conflicts Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979), which asked participants if they had experienced psychological, sexual, and/or physical abuse over the past 12 months. The Add Health data set contains a total of eight items assessing intimate partner violence (four items assessing perpetration and four items assessing victimization). Items to assess perpetration were, “How often have you threatened <PARTNER> with violence, pushed or shoved {HIM/HER}, or thrown something at {HIM/HER} that could hurt” (psychological IPV), “How often have you slapped, hit, or kicked <PARTNER>“ (physical IPV), “How often have you insisted on or made <PARTNER> have sexual relations with you when {HE/SHE} didn’t want to” (sexual IPV), and “How often has <PARTNER> had an injury, such as a sprain, bruise, or cut because of a fight with you?” (Occurrence of injury from IPV). Items were reverse-worded to assess victimization. All items were rated on a 7-point scale from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Men and women’s IPV perpetration and IPV victimization (in form of latent variables)1 were used as the outcomes in the present study. Additional analyses were conducted exploring the associations between men’s and women’s empathy and their own as well as their partners levels of psychological, physical, and sexual IPV perpetration and victimization, and occurrence of injury from IPV (here the IPV outcome was assessed using the individual IPV observed variables).

Covariates.

Men’s and women’s cohabitation and marital status were included as covariates in all analyses. Cohabitation status (currently cohabitating versus non-cohabitating) was assessed with the item, “We’d like to know if you and {INITIALS} currently live together, or lived together at some time in the past. Please select the sentence below which best describes your relationship.” Marital status (currently married versus non-married) was assessed with the item, “We’d like to know if you and {INITIALS} are currently married, or were ever married. Please select the sentence below which best describes your relationship.”

For men’s and women’s means, standard deviations, and percentages of participants in each group for all study variables, please refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Men’s and Women’s Means, Standard Deviations and Percentages of Participants in each Group for all Study Variables

| Study Variables | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | % | M | SD | % | |

| Empathy Mean | 5.37 | 1.19 | -- | 5.59 | 1.06 | -- |

| Perpetration Suma | 0.60 | 1.79 | 19.0 | 1.19 | 2.39 | 32.2 |

| Victimization Suma | 1.08 | 2.59 | 25.4 | 0.89 | 2.23 | 24.0 |

| Cohabitating | -- | -- | 72.6 | -- | -- | 71.4 |

| Married | -- | -- | 37.5 | -- | -- | 37.2 |

% defined as percentage of individuals experiencing 1 or more acts of IPV

Analytical Approach

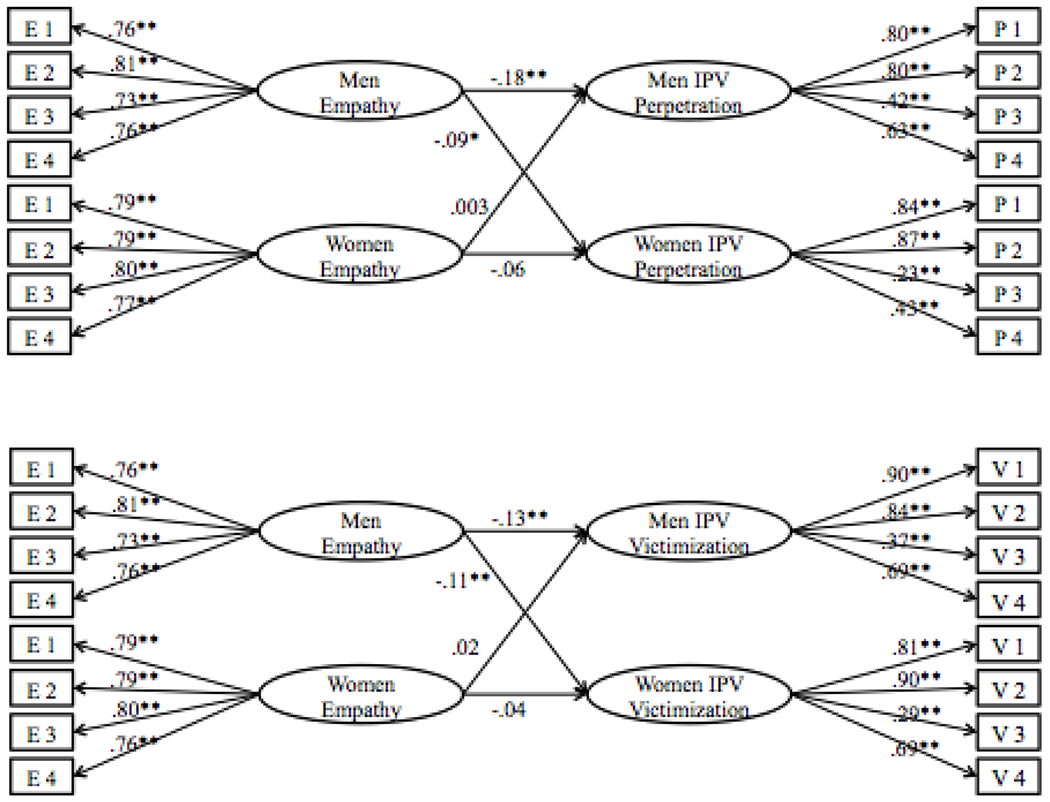

A path-analytic approach was used to assess the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny et al., 2006). Model 1 included the latent variables men’s empathy, women’s empathy, men’s IPV perpetration, and women’s IPV perpetration, which were indicated by four observed variables each (corresponding to the individual empathy and IPV perpetration items described in the measures section). In the APIM, men and women’s empathy were added as antecedents and men and women’s IPV perpetration were added as outcome variables (see Figure 1). Direct paths from men’s empathy to men’s IPV perpetration and from women’s empathy to women’s IPV perpetration (actor effects) as well as from men’s empathy to women’s IPV perpetration and from women’s empathy to men’s IPV perpetration (partner effects) were modeled. In addition, cohabitation status and marital status were entered into the model. Because partners have influence over each other and share many common experiences, data collected from partners are never independent. Failing to account for this lack of independence in data analysis can bias significance tests of the overall model (Kenny et al., 2006). Therefore, we allowed men’s and women’s empathy and IPV perpetration scores to correlate with each other. Model 2 was concordant with Model 1, except for the inclusion of men and women’s IPV victimization in the model instead of men and women’s IPV perpetration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model for the Associations between Empathy and IPV Perpetration (Model 1) and Victimization (Model 2).

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01. E1-E4 = Empathy observed variables 1-4, P1-P4 = IPV perpetration observed variables 1-4, V1-V4 = IPV victimization observed variables 1-4.

After running these two overall models for IPV perpetration and victimization, we re-ran both models using the four observed IPV variables as outcomes instead of the IPV latent variables indicated by these four observed variables. More specifically, Model 3 included the latent variables men’s empathy and women’s empathy and the observed variables men’s and women’s psychological, physical, sexual IPV perpetration, and perpetration of injury. Men’s and women’s empathy were added as antecedents and men’s and women’s psychological, physical, sexual IPV perpetration, and perpetration of injury were added as separate outcome variables. Direct paths from men’s empathy to men’s and women’s psychological, physical, sexual IPV perpetration, and perpetration of injury and from women’s empathy to men’s and women’s psychological, physical, sexual IPV perpetration, and perpetration of injury were modeled. As in Models 1 and 2, cohabitation status and marital status were entered into the model and men’s and women’s empathy and psychological, physical, sexual IPV perpetration, and perpetration of injury were allowed to correlate with each other. Model 4 was concordant with Model 3, except for the inclusion of men and women’s psychological, physical, sexual IPV victimization, and receipt of injury instead of men’s and women’s psychological, physical, sexual IPV perpetration, and perpetration of injury.

Overall goodness of fit was not determined statistically or descriptively since the basic APIM is a saturated model (Cook & Kenny, 2005). The goal of the analyses was to determine the actor and partner effects and not the overall fit of the model. Furthermore, because the couple was the unit of analysis in the present study, there was no need to correct for the Add Health design effects using the weights provided.

Results

Model 1: Empathy and IPV Perpetration

Results of Model 1 support the hypothesis that lower empathy among men would be associated with higher levels of IPV perpetration among men and women. As can be seen in Figure 1, all standardized factor loadings in Model 1 were generally large and statistically significant for empathy (values ranged from .73 to .81 for men and from .77 to .80 for women) and IPV perpetration (values ranged from .42 to .80 for men and from .23 to .87 for women) 2. The actor effect for men as well as the partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s perpetration were found to be significant. More specifically, the lower men’s empathy, the greater men’s IPV perpetration (β = −.18, p < .001) and the greater women’s IPV perpetration (β = −.09, p = .01). The actor effect for women (β = −.06, p = .10) and the partner effect from women’s empathy to men’s perpetration (β < .01, p = .93) were found to be non-significant (see Figure 1).

Model 2: Empathy and IPV Victimization

Results of Model 2 support the hypothesis that lower empathy among men would be associated with higher levels of IPV victimization among men and women. As can be seen in Figure 1, all standardized factor loadings in Model 2 were generally large and statistically significant for empathy (values ranged from .73 to 81 for men and from .77 to .80 for women) and IPV victimization (values ranged from .37 to .90 for men and from .29 to .90 for women). The actor effect for men and the partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s victimization were found to be significant. More specifically, the lower men’s empathy, the greater men’s IPV victimization (β = −.13, p < .001) and the greater women’s IPV victimization (β = −.11, p = .002). The actor effect for women (β = −.04, p = .27) and the partner effect from women’s empathy to men’s victimization (β = .02, p = .60) were found to be non-significant (see Figure 1).

Models 3 and 4: Individual IPV Outcomes

Because the analyses of Models 3 and 4 relied on individual items as IPV outcomes and thus may not be as powerful and rather exploratory in nature, these results are only briefly described here due to space limitations. All standardized factor loadings with corresponding levels of significance for Models 3 and 4 can be found in Table 2. For more detailed information, please contact the first author.

Table 2.

Standardized Regression Coefficients for the Associations between Men’s and Women’s Empathy and their Psychological, Physical, Sexual IPV, and Injury Perpetration (Model 3) and Victimization (Model 4)

| Outcome | Predictor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model 3 (Perpetration) |

Model 4 (Victimization) |

|||

|

|

||||

| Empathy M | Empathy W | Empathy M | Empathy W | |

|

|

||||

| Psychological IPV M | −.16*** | −.08* | −.12*** | −.13*** |

| Psychological IPV W | −.05 | −.04 | <. 01 | −.05 |

| Physical IPV M | −.14*** | −.06 | −.12*** | −.08* |

| Physical IPV W | .04 | −.04 | .03 | −.02 |

| Sexual IPV M | −.11** | −.04 | −.04 | −.01 |

| Sexual IPV W | .02 | −.11** | .03 | −.06 |

| Injury M | −.07* | −.12** | −.02 | −.07* |

| Injury W | .02 | −.08* | .01 | −.05 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

IPV = Intimate Partner Violence, M = Men, W = Women. Covariates included in all analyses.

For IPV perpetration, the results of Model 1 partially generalized to Model 3 (all significant effects in Model 3 were in the same [negative] direction as in Model 1). The results of Model 3 were exactly concordant with Model 1 for psychological IPV perpetration only (i.e., there were a significant actor effect for men and a significant partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s psychological IPV perpetration). For physical IPV perpetration, there was a significant actor effect for men. For sexual IPV perpetration, there were a significant actor effect for men and a significant actor effect for women. For perpetration of injury, there were a significant actor effect for men, a significant actor effect for women, and a significant partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s perpetration of injury.

For IPV victimization, the results of Model 2 partially generalized to Model 4 (all significant effects in Model 4 were in the same [negative] direction as in Model 2). The results of Model 4 were exactly concordant with Model 2 for psychological IPV and physical IPV victimization (i.e., there were a significant actor effect for men and a significant partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s psychological and physical IPV victimization). For sexual IPV victimization, there were no significant effects. For receipt of injury, there was a significant partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s receipt of injury.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the association between partners’ dispositional empathy and their levels of overall IPV perpetration and victimization. Findings of the current analyses support our predictions (when assessing overall levels of IPV perpetration and victimization comprised of different types of IPV). For both IPV perpetration and IPV victimization, a significant actor effect for men and a significant partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s IPV were found, indicating that lower dispositional empathy among men was associated with higher levels of IPV perpetration and IPV victimization among men and among women. No significant effects between women’s dispositional empathy and either their own or their partners’ levels of IPV perpetration or victimization emerged. These findings are concordant with previous research on empathic accuracy showing that only men but not women had deficits in correctly inferring others’ feelings and emotions and, consequently, behaved more aggressively (Clements et al., 2007; Schweinle et al., 2002). Furthermore, these findings extend previous work by Peloquin et al. by indicating that the association between empathy and overall IPV differed from the association between empathy and psychological IPV. Whereas Peloquin et al. (2011) found significant actor effects for men and women but did not find any partner effects, results of the present study indicate that there were significant actor and partner effects, however only for men and not for women. It may be that different mechanisms are at play when considering partners’ overall levels of aggression, including their psychological, physical, and sexual aggression, as opposed to solely their psychological aggression.

Due to previous research showing that aggression in violent relationships, especially among community couples such as the couples included in the present study, tends to be much more gender-symmetric than previously thought (Archer, 2000), the gender differences detected in the current analyses may be quite important. While men’s empathy was found to be associated with both their own and their female partners’ aggressive behaviors, no such associations were found between women’s empathy and partners’ IPV. It is important to acknowledge that previously developed explanations for male IPV may not be applicable to female IPV (Clements et al., 2007). As such, the present findings show that men’s levels of empathy may carry more weight in determining their own as well as their partners’ aggressive behaviors than do women’s levels of empathy. It is possible that the lack of significant associations between women’s empathy scores and men’s and women’s IPV may be due to the fact that women generally had higher empathy scores than men. These empathy scores may have reached a ceiling so that further increases in empathy scores did not affect IPV (see Rowan, Compton, & Rust, 1992). Alternatively, it may be that men’s empathy does in fact play a more important role in romantic relationships than women’s empathy. A possible reason may be that men who fail to take care of their partners by not being understanding and compassionate violate society’s perception of men as the protectors of the family (Hood, 1986). This violation may result in discomfort, which may be expressed in the form of IPV by both partners. Furthermore, since society may perceive women as the more empathic gender in romantic relationship, women’s empathic behavior is expected and does thus not have as strong of an impact on men’s and women’s IPV as does men’s empathic behavior. Finally, it is also commonly expected that female-perpetrated IPV is much more tolerated and excused compared to male-perpetrated IPV. This may explain why some women are violent despite having better communication and emotion management skills compared to men. Large representative sample surveys by Straus, Kaufman-Kantor, and Moore (1997) and Simon et al. (2001) found far greater public approval for slapping by wives than for slapping by husbands, although in both studies female respondents were less approving of IPV overall relative to male respondents. From a presentation of vignettes of domestic violence situations in a large random-digit-dialed survey by Sorenson and Taylor (2005), male and female respondents were equally likely to judge violence against women more harshly, given the same circumstances, and were more likely to take into account contextual factors than when men are violent. These differential attitudes regarding the acceptability of IPV across gender may provide possible explanations for the current results.

The previously discussed findings partially generalized to analyses examining actor and partner effects of the association between empathy and the different types of IPV (psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and occurrence of injury) separately. Here, the conclusions discussed above may apply. Some results, however, deviated from the overall pattern. For physical IPV perpetration, we did not find the previously observed partner effect. For sexual IPV perpetration, we also did not find the previously observed partner effect; however, we did find an additional actor effect for women. Finally, for perpetration of injury, we found a significant actor effect for women in addition to the previously observed actor and partner effects. It may be that for sexual IPV perpetration and perpetration of injury, women’s empathy has a larger impact on their own levels of perpetration than for the other types of IPV in that women who are more empathic are less likely to perpetrate sexual IPV and inflict injuries on their male partners.

For sexual IPV victimization, none of the effects were significant. For receipt of injury, only the partner effect from men’s empathy to women’s receipt of injury was significant. It may be that partners’ empathy has little to no impact on whether they will be sexually victimized by an intimate partner, because other factors might override (e.g., sexual urges drives as well as power and domination) the effects of empathy in this context. Similar processes might be applicable to receipt of injury. It is interesting to note that a significant partner effect from women’s empathy to men’s IPV perpetration or victimization was detected in none of the analyses, showing that women’s levels of empathy may not be associated with men’s behaviors in this context.

It is important to keep in mind that the analyses assessing the different types of IPV were based on individual item measures of IPV, which might limit the conclusions that can be drawn. However, the present findings shed some light on the differential relationships between empathy and psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and occurrence of injury from IPV that may hopefully stimulate researchers’ interest in further examining these associations.

Strengths and Limitations

Several features of the present study’s design and methodology enhance our confidence in the findings reported here. First and foremost, the use of the APIM and a dyadic data analysis design offers several advantages over approaches based on individual-level data: This approach addresses the non-independence of dyadic data, integrates both actor effects and partner effects in the same analysis, and allows for the correlation of independent variables (i.e., men’s and women’s empathy; Kenny, et al., 2006). Furthermore, while many previous studies have focused on exclusively examining male aggression, the present study also examined female aggression. In addition, the measurement of both IPV perpetration and victimization and the fact that the same results were found in both of these models (thereby ruling out biases in the reporting of acts of IPV perpetration and victimization) enhance our confidence in our findings. Moreover, although based on individual items, we were able to assess separately the associations between empathy and different types of IPV perpetration and victimization (psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and occurrence of injury from IPV). Finally, the large, representative sample used in the present study provided high power, increasing the chances of detecting existing effects, and may allow us to conclude that the current findings may be generalizable across the larger population of community couples.

Nevertheless, several factors limit interpretation of the current findings. The use of a correlational design prevents us from inferring causal relations between the study variables. In addition, although the present sample was large, it is important to consider that it was a community sample, as opposed to a clinical sample. Thus, it remains unclear whether the present findings would generalize to clinical populations. Furthermore, the present study relied solely on self-report measures to assess both empathy and IPV. In addition, the empathy measure was not simply a self-report measure, but rather a measure of subjective self-evaluation in that it asked participants to interpret as how empathic they perceived themselves. It may be that, although individual participants perceived themselves as empathic, their partners may not agree with these self-evaluations. Thus, the use of a multi-method approach, including both relatively objective self-reports as well as behavioral observations (e.g., Specific Affect Coding System; Gottman, McCoy, Coan, & Collier, 1996) or physiological indexes of empathy (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1990) might be more advantageous and might provide richer and more generalizable data than the current methodological design. Moreover, the measures used to assess empathy and IPV, although based on well-established and validated measures, did not include the complete sets of items of these established measures. Although we were able to assess the associations between empathy and different types of IPV (psychological, physical, sexual IPV, and occurrence of injury) separately, our IPV outcome measures were based on individual observed variables, which might limit interpretation of the current results. Finally, the effect sizes detected in the present study were relatively small, which may indicate that the association between empathy and IPV may not be as strong as previously thought. In fact, a recent meta-analysis (Vachon, Lynam, & Johnson, 2013) provides support that the true association between empathy and general aggression, although significant, may be surprisingly weak.

Research Implications

Despite such limitations, the present study provides interesting findings that require future replication. First and foremost, longitudinal studies are needed to properly investigate the relation between empathy and IPV. In addition, replications of this research in similar (i.e., community) samples will suggest how generally applicable our findings are. Furthermore, it would be interesting to replicate this research in different samples, such as clinical samples or samples of couples from other countries and cultures, to see whether the current findings would generalize to these groups. Furthermore, future studies should consider using complete, reliable, and valid established measures as well as measures other than self-report. It is important to examine whether the present findings showing slightly differential associations between empathy and psychological, physical, and sexual IPV would generalize to studies using complete measures assessing the different IPV types. Finally, future research on empathy and IPV might attempt to address the mechanisms that may underlie the associations and gender differences detected in the present study. For example, future studies on could include additional variables, such as pro-violent attitudes and motivation, which might help explain the differential empathy-IPV association among men and women.

Practical Implications

Teaching batterers to become aware and respond to the damage they cause their victims has been a common feature of treatment programs for violent offenders in general and offenders of domestic violence in particular (Dobash, Dobash, Cavanagh, & Lewis, 2000; Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004). The present findings lend support that incorporating empathy skills training into treatment may in fact be effective in helping reduce future incidents of IPV. Empathy training may be especially useful for men in that low empathy among men was not only found to be associated with their own but also with their female partners’ IPV perpetration and victimization. Thus, couples interventions promoting the expression of empathy in partners would be a suitable avenue, at least for community couples who occasionally resort to aggression to resolve relationship problems. Finally, it may be valuable for clinicians to assess which specific types of IPV couples experience, as the present findings indicate that the associations between empathy and psychological, physical, and sexual IPV perpetration and victimization, at least to some extent, may differ.

Couples interventions that include an empathy component already exist: For example, Emotion-Focused Couple Therapy (EFT; Greenberg & Johnson, 1988; Johnson, 2004) promotes partners’ empathic understanding of each other’s emotional experiences, thereby developing a sense of safety in the relationship. However, it is important to keep in mind that this type of therapy may not be appropriate for severely aggressive couples for whom couples therapy may represent danger. For such couples, it is recommended that partners work on anger-control management issues as well as empathy on an individual basis before undergoing couples therapy with their partner (Peloquin, et al. 2011).

Conclusions

The present study suggests that a lack of empathy, including a lack of sympathy, sensitivity, understanding, and compassion, may translate into adverse behaviors, such as overall intimate partner violence. Interestingly, only men’s empathy was found to be associated with both their own as well as their partners’ levels of IPV, whereas no such association was found between women’s empathy and IPV. These findings provide support for the conclusion that theoretical models developed to explain IPV and strategies commonly employed to prevent IPV among men may in fact not be applicable to women. Clearly, additional research replicating the present findings in different kinds of samples and examining the mechanisms that may help explain the association between empathy and IPV as well as potential gender differences is warranted. It will also be of value to further examine the potentially differing associations between empathy and psychological, physical, and sexual IPV. However, the present findings may provide a useful basis for such future studies and may be beneficial in helping practitioners and policy makers in developing IPV prevention or intervention programs, specifically aimed at enhancing men’s empathic behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Footnotes

Due to previous research (e.g., Hamby, 2009) showing that one partner’s IPV perpetration scores do not always completely overlap with the other partner’s victimization scores (also supported in present findings, see Table 1), IPV perpetration and victimization were assessed separately in the present study. Separate models were run for perpetration and victimization to allow for comparison of results.

Standardized factor loadings for the third IPV (both perpetration and victimization) observed variables for men and women, assessing sexual IPV, were relatively low in all analyses. However, we decided not to drop this observed variables for reasons of completeness in the already rather short IPV measures.

References

- Archer J (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 651–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Fultz J, & Schoenrade PA (1987). Adults’ emotional reactions to the distress of others. In Eisenberg N, & Strayer J (Eds.), Empathy and its development (pp. 163–184). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge. University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2011). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization — National intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6308a1.htm?s_cid=ss6308a1_e [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2012b). Understanding teen dating violence. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/TeenDatingViolence2012-a.pdf

- Christopher F, Owens LA, & Stecker HL (1993). Exploring the darkside of courtship: A test of a model of male premarital sexual aggressiveness. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55(2), 469–479. [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Schweinle W, & Ickes W (2007). Empathic accuracy of intimate partners in violent versus nonviolent relationships. Personal Relationships, 14(3), 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, & Strayer J (1996). Empathy in conduct-disordered and comparison youth. Developmental Psychology, 32, 988–998. [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, & Kenny DA (2005). The actor-partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Covell C, Huss M, & Langhinrichsen-Rohling J (2007). Empathic deficits among male batterers: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Family Violence, 22(3), 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dobash RE, Dobash RP, Cavanagh K, & Lewis R (2000). Changing violent men. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, & Fabes RA (1990). Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motivation and Emotion, 14, 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky AM, & Sonenstein FL (2011). The association between developmental assets and sexual enjoyment among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(6), 610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J, McCoy K, Coan J, & Collier H (1996). The specific affect coding system (SPAFF). In Gottman J (Ed.), What predicts divorce? The measures (pp. 1–169). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS, & Johnson SM (1988). Emotionally focused therapy for couples. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S (2009). The gender debate about intimate partner violence: Solutions and dead ends. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(1), 24. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, & Udry JR (2009). The national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health: Research design. Retrieved Oct. 9, 2014, from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design

- Hood JC (1986). The provider role: Its meaning and measurement. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 48(2), 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM (2004). The practice of emotionally focused couple therapy: Creating connection (2nd ed.). New York: Brunner-Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe D, & Farrington DP (2004). Empathy and offending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(5), 441–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Analyzing mixed independent variables: The actor-partner interdependence model. In Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (Eds.), Dyadic data analysis (pp. 144–184). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller PA, & Eisenberg N (1988). The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 324–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péloquin K, Lafontaine M, & Brassard A (2011). A dyadic approach to the study of romantic attachment, dyadic empathy, and psychological partner aggression. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(7), 915–942. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S, McFarlane J, & Banyini M (2013). Mental health consequences of intimate partner violence in Vhembe district, South Africa. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(5), 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DR, Hammock GS, Smith SM, Gardner W, & Signo M (1994). Empathy as a cognitive inhibitor of interpersonal aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 20(4), 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan D, Compton W, & Rust J (1995). Self-actualization and empathy as predictors of marital satisfaction. Psychological Reports, 77(3 Pt 1), 1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinle WE, Ickes W, & Bernstein IH (2002). Empathic inaccuracy in husband to wife aggression: The overattribution bias. Personal Relationships, 9(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Simon T, Anderson M, Thompson M, Crosby A, Shelley G, & Sacks J (2001). Attitudinal acceptance of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults. Violence and Victims, 16(2), 115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson S, & Taylor C (2005). Female aggression toward male intimate partners: An examination of social norms in a community-based sample. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (1979). Measuring intra-family conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Kaufman-Kantor G, & Moore D (1997). Change in cultural norms approving marital violence from 1968 to 1994. In Kantor G. Kaufman & Jasinski J (Eds.), Out of the darkness: Contemporary perspectives on family violence (pp. 3–16). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Leonard KE (2001). The impact of marital aggression on women’s psychological and marital functioning in a newlywed sample. Journal of Family Violence, 16(2), 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon D, Lynam D, & Johnson J (2013). The (non)relation between empathy and aggression: Surprising results from a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 751–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]