Abstract

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic created a shift from traditional face-to-face learning toward remote learning, resulting in students experiencing unforeseen challenges and benefits through participation in a non-traditional mode of education. Little is known regarding the impact that a shift to remote learning may have had on the learning experiences and the career goals of Master of Public Health (MPH) students. A qualitative study was conducted among a convenience sample of MPH students in the US from January to April 2021. The primary aims were (1) to describe salient challenges or benefits of learning that persisted throughout a semester of remote learning and (2) to describe how being in graduate school during the pandemic impacted students’ career goals in public health. A secondary aim was to describe students’ general feelings regarding their public health education, given their lived experience of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Study findings demonstrated that MPH students had mixed perceptions of how a shift to remote learning during a public health crisis impacted their learning experiences and career goals in public health over one semester. Understanding students’ responses can guide public health instructors to best prepare trainees to join the workforce during ongoing and future unforeseen public health crises that continue or have the potential to disrupt learning modalities.

Keywords: career goals, COVID-19, master of public health, public health education, remote learning

Introduction

Prior to the pandemic, schools of public health began offering degree programs and courses via online, hybrid, blended, and other forms of remote learning (Kiviniemi, 2014; So, 2009; Walker et al., 2021), however, most schools continued to provide traditional face-to-face learning experiences. Thus, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the rapid shift to remote learning may have challenged students who were not prepared to engage in learning through remote environments. Little information is available on the impact that a shift to remote learning may have had on the educational experiences, and career goals of Master of Public Health (MPH) graduate students, who are typically enrolled in 2-year programs.

The shift to remote learning means students will experience new challenges and benefits in this new mode of education. For example, a study published among undergraduate and graduate public health students reported that they experienced issues with internet connectivity and increased academic workload due to the pandemic within the first term/semester of remote learning (Armstrong-Mensah et al., 2020). A separate study among graduate students found that the most reported problems students experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic included issues with decreased productivity and poor physical and emotional well-being (Wasil et al., 2021), while other studies that emerged during the pandemic demonstrated unforeseen benefits of the pandemic, such as greater flexibility and convenience of learning and accessibility to class recordings (Chhetri, 2020). A prepandemic study among students enrolled in an online MPH program found that program predictors of student success included alignment between program expectations and learning and teaching styles (Alperin, 2015), indicating that an abrupt shift to remote learning may not meet students’ expectations for learning. As the pandemic ensues and remote, hybrid, or flexible learning continues, the long-term challenges or benefits to these various learning environments that are embedded in residential in-person programs have yet to be explored.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic may be temporary, the impact of shifting from traditional face-to-face learning to remote learning will likely have lasting effects on trainees’ career goals. For example, in a study involving nearly 8,000 postdoctoral scholars worldwide, 61% reported that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected their career prospects (Woolston, 2020). In contrast, the field of public health saw increases in MPH applications, with one report mentioning that the number of applicants using the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) Schools of Public Health Application Service (SOPHAS) was 40% higher in March 2021 compared to March 2020, with thousands of students considering the field of public health (Warnick, 2021). Although it is unclear why the field saw an increase in applicants, it is plausible that the pandemic led first-time applicants to be more exposed or introduced to the field. While a recently published study found that the pandemic had a positive influence on students’ desire to seek careers and further training in public health (Gamber et al., 2022). The MPH core competency model supports students’ career goals by developing targeted professional skills, like designing population-based policy, through applied and experiential learning elements. Thus, it is crucial to understand if students’ career goals were supported and developed as learning environments shifted.

This qualitative longitudinal study utilized a convenience sample of MPH students to describe their perceptions and experiences related to remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic on their learning and public health career goals. Specifically, the present study aims to (1) describe salient challenges or benefits of learning that persisted throughout a semester of remote learning and (2) describe how being in graduate school during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted students’ career goals in public health. A secondary aim was to describe students’ general feelings regarding their public health education, given their lived experience of remote learning during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Participant Recruitment

The present study was conducted among public health graduate students enrolled in an accredited MPH program at a school of public health located within a large Midwestern public university in the United States. MPH students were eligible to participate in the study if they were currently enrolled in the residential MPH program at the university during the Winter 2021 term (January and April 2021). Convenience sampling was implemented to recruit students. Specifically, an e-mail invitation was distributed to all eligible MPH students (N = 371) on departmental listservs at the school of public health. The first 50 students (13.5% of the total MPH student population) that provided informed consent were enrolled in the study. We opted to limit study enrollment to 50 students due to funding constraints related to adequately compensating participants for investing time into participating in the study. Each participant received a $50.00 Visa gift card for completing all components of the study.

Of note, the public health program the participants were enrolled in was traditionally residential (i.e., in-person). Coincidently the school of public health did launch an online program in 2019/2020 academic year, but only a handful of faculty opted in or had taught in the online program at that time. Additionally, it is important to note that the intentions and student population of the online program is different from the remote learning setting.

Data Collection

The longitudinal study was conducted between January and April 2021. It included four data collection points, whereby a survey was distributed once each month. The self-administrated, semi-structured survey composed of open- and closed-ended questions and prompts were used at each time-point (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). At each time-point, participants had the opportunity to complete the surveys within 1 week of distribution.

Participants completed a close-ended demographic survey questionnaire at time-point one (distributed and completed in January 2021). We collected students’ demographics, including age, gender, program year, race/ethnicity, the number of courses in which the student was enrolled, employment status, and the total number of household members, as well as self-reported social identities: first-generation college student, underrepresented minority (URM), low-income student, disabled, member of one or more marginalized groups, none of the above, other, or do not know. Additionally, we included open-ended reflective prompts to obtain information on participants’ personal experiences learning as a public health student during the past 6 months (i.e., approximately capturing experiences from the Fall 2020 term).

Participants completed a survey at time-point two (distributed and completed in February 2021). The open-ended reflective writing prompts were structured as described for time-point one. However, instead of focusing on the past 6 months, the prompts asked participants to reflect on their experiences with remote learning during the past month, January to February 2021. Similarly, prompts at time-point three (distributed and completed in March 2021) asked participants to reflect on their experiences with remote learning during the past month (February to March 2021). In contrast to data collected at time-points one through three regarding reflecting on experiences with remote learning, at time-point four (distributed and completed in April 2021) participants were asked to describe how remote learning impacted their career goals in public health.

Finally, at each of the four time-points, participants were asked to provide a one-sentence quote that summarized their feelings, in general, about their public health education at different points during the academic year. The prompt read as follows: “provide a one-sentence quote summarizing your feelings over the past 6 months regarding your public health education.” At time-points two and three, the prompt read as follows: “regarding your public health education: provide a one-sentence quote summarizing your feelings at this point in the semester.” At time-point four: “provide a one-sentence quote summarizing your feelings about your public health education as the semester ends.”

Data were downloaded from Qualtrics by a researcher not associated with the school of public health to blind project investigators from participant names. Each participant was given a unique identifier to ensure the data-set was de-identified before being shared with project investigators.

Coding and Thematic Analysis

Data were included in the analysis from participants who completed surveys at four time-points; participants with incomplete data from at least one time-point were excluded from the analytic sample. Qualitative data obtained from participant responses was analyzed using an inductive thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998). Specifically, we implemented a data-led thematic analysis approach in which emerging patterns and themes were determined a posteriori. Two project investigators individually segmented data into codes (i.e., a single word or phrase that reflected an opinion, thought, or feeling in response to the reflective prompts). Both investigators independently grouped similar codes to generate related themes. Investigators iteratively conducted the process of coding and developing themes to increase the reliability of the analysis. After independent analysis by each investigator, discrepancies were identified and discussed amongst the entire research team to reach a consensus. Themes were summarized to provide an overall picture of students’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of remote learning and how remote learning may have shifted their career goals development. Investigators reviewed participant responses to identify critical quotes representing the identified themes.

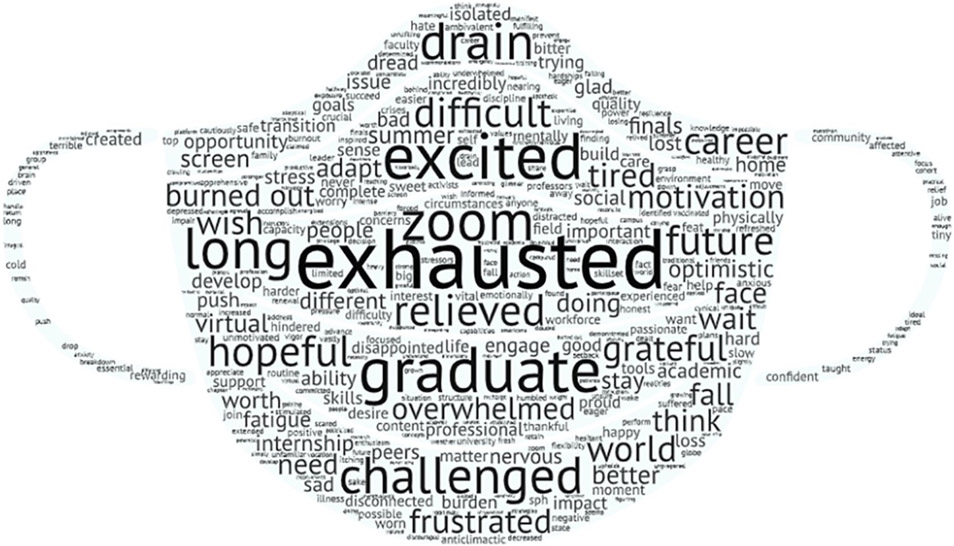

Word cloud creation.

Using open-ended data collected across all four time-points (Jan–April 2021), an investigator created a word cloud (WordArt 2021) to visually present the frequency of participants’ most salient feelings regarding their public health education during the academic term by inputting participants’ one-sentence responses from each time-point. The size of each word or phrase in the cloud represents the frequency of use. Additionally, before inputting one-sentence responses into the software, the investigator removed “stop-words” (i.e., the, to) using software specifications. This was done to eliminate words that did not provide meaningful information.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using frequencies and percentages to summarize the participants’ responses. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The study was determined to be exempt by the University Institutional Review Board (HUM00190362).

Results

Among the 50 participants enrolled in the study, 47 (94%) completed data at all four time-points and were included in the analytic sample.

Participant Demographics

Participant demographics have been previously published elsewhere (Zamora et al., 2022). Approximately 77% (36/47) of participants identified as female, 64% (30/47) reported being 20 to 24 years old, and 62% (29/47) reported being non-Hispanic white. Nearly one-third (28%; 13/47) identified as first-generation college students, while 32% (15/47) were low-income. Approximately half (53%; 25/47) of participants were second-year MPH students, while two-thirds (66%; 31/47) of participants reported being full-time students and employed either full- or part-time.

Thematic Analysis of Perceived Challenges and Benefits From Remote Learning

When participants reflected on experiences with learning as public health students during the past 6 months (time-point one) and past month (time-points two and three), central themes that emerged primarily included challenges and some benefits. Challenges that emerged involved poor mental/emotional health, physical health, lack of interactions, and loss of opportunities, among other challenges. General reports of beneficial impacts included greater accessibility of course materials, flexibility around courses, and the ability to hold part-time jobs. Table 1 presents the major themes, frequencies, and representative quotes.

Table 1.

Longitudinal Thematic Analysis From Written Reflections Regarding Challenges, Benefits, and Other Experiences With Remote Learning Among Participants (N = 47).

| Thematic word classification |

Representative quotes abstracted from reflections #1-#3 | Reflection #1 (January 2021) n (%)a |

Reflection #2 (February 2021) n (%)b |

Reflection #3 (March 2021) n (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived challenges | ||||

| Poor mental/emotional health impacts | I have less interest in stuff, feeling more fatigued, and in general just struggling to find motivation in day-to-day life. My mental health has taken a hit because of online learning and feeling overwhelmed by work and school. COVID-19 has impacted has continued to impact my learning because continued isolation has greatly impacted my mental health and by extension my ability to stay engaged in my classes and my motivation to keep up. |

37 (78.7) | 38 (80.8) | 31 (66.0) |

| General challenges | The repetitive nature of zoom courses and virtual life has started to become taxing All of this has definitely affected my motivation regarding course content as I struggle to feel excited about learning this information. I also believe this has affected how I talk to other public health students. We are all exhausted from explaining the benefits of mask wearing and vaccines to those in our circles. We have become the public health experts to our friends and family even though we are not even done with our degrees. This makes it challenging to have discussions about anything other than the pandemic or corresponding injustices happening in the United States. |

26 (55.3) | 8 (17.0) | 8 (17.0) |

| Zoom fatigue/anxiety | Zoom fatigue was another major issue I faced. It was difficult for me to maintain a higher level of class engagement over video Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, being online and behind a screen most of the day everyday has made it challenging to focus and be as productive as I normally am. |

18 (38.3) | 17 (36.2) | 13 (27.7) |

| Physical health impacts | It’s also [remote learning] impacted my physical health, making it hard to maintain a healthier lifestyle and level of energy. |

14 (29.7) | 6 (12.8) | 4 (8.5) |

| Lack of interactions | The logistics of learning have also been a challenge, and I think the hardest part is making connections with professors. I find it difficult to make personal connections over online formats such as Zoom and email, and I am worried that this will be detrimental to my eventual career search after graduation, as professors are often great contacts to job opportunities/alumni. Having remote classes this semester has made it much more difficult for me to connect with my professors on a one-on-one basis. I can’t just stop by professors offices for office hours, something I would normally be regularly doing. Instead, every one-on-one with my professors had to be planned ahead of time and typically was more limited in time. The virtual nature of classes has also decreased collaboration and social interaction with my classmates which has taken away from my graduate experience and created more feelings of isolation. This has also had a negative impact on my motivation. |

32 (68.0) | 21 (44.7) | 12 (25.5) |

| Loss of opportunities | It almost seems pointless to search for internships and future opportunities when so much is to be determined. The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected my feelings toward learning public health course content because it took away the opportunities for me to have an internship over the summer of 2020 I’ve been so disappointed that internships opportunities have been remote because I’m just tired of sitting in my house. It’s caused me a lot of grief and stress. They [holding two part time jobs] don’t make up for not getting an internship and finding a full-time job has been very difficult but I am still doing my best to make the most of it with the experiences I have. |

23 (48.9) | 7 (14.9) | 7 (14.9) |

| Learning course content | Challenges that arose in my learning from COVID-19 were professors not shifting their content to be engaging for online learning. Logistically, learning has been a bit of a challenge because professors are assigning a lot of group work for final projects, and that is challenging to do in a remote format, but at this point I think I have more or less gotten used to it, and I can just deal with it. |

26 (55.3) | 25 (53.2) | 17 (36.2) |

| Implementing coping mechanisms | I look at my computer all day for class, then continue my homework on my computer, then attend all my meetings also on my computer. It has made me have to better manage my life outside of school to improve my mental health. I go for more walks than I ever have and I also read more than I used to. Some strategies I have implemented include trying to get outside for a walk or run every day, taking breaks from my screen to relax, listen to music and move my body, and taking meetings on my phone so I can walk outside or do something else at the same time instead of sitting at a desk all day. |

16 (34.0) | 7 (14.9) | 7 (14.9) |

| Lack of university support | We are expected to perform at high quality without receiving high quality education and/or much support from the university. I just feel really alone without university support, trying to navigate my program, what classes to take, etc. |

8 (17.0) | 6 (12.8) | 9 (19.2) |

| Perceived benefits | ||||

| Motivated to continue pursuing public health education/career and/or public health opportunities | I have found more ways of how I can be of help during this pandemic and have also been given more job opportunities to do so because of the pandemic. I have two part time positions where I work “full time” in a week. I believe this has impacted my education more than remote learning ever will. I also believe that if it was not for the pandemic, I would not have these two part time positions in the first place because they are COVID-19 related. The COVID-19 pandemic has motivated me as a public health student during my first year of my masters. I have been working full time on the front lines as a grocery store employee while doing my 18+ credits of schooling every semester. I find that as I see and encounter the topics that I am learning in my different classes in several aspects of my daily life be it at work etc., it only motivates me further to learn more about public health. The COVID-19 pandemic has made me even more passionate about public health and has given me a greater appreciation for the field I am going in to. I am grateful to be in an MPH program during this time because I feel like I am obtaining the facts about COVID-19 and understand what is going on in the world. Nonetheless, COVID-19 has definitely increased my desire to enter the Public Health workforce and has also motivated me to acquire/expand my quantitative skills and ability to analyze data by using tools such as GIS and R. |

4 (8.5) | 4 (8.5) | 5 (10.6) |

| Support from faculty, staff, etc. | Fortunately, all professors were open and willing to provide any extra help needed to really understand the course material. However, there have been some positive experiences including great support from staff. They’ve really helped motivate myself and others, giving us tools to navigate the rest of the semester. It’s definitely shifted my perspective a bit on the impact of COVID-19 on my personal life and mental health. This experience has also made me very appreciative of professors and their flexibility in instruction, due dates and type of assignments. I also have less worry about grades as grading has been more lenient and I care much less about letter grades as a result of this experience. |

1 (2.1) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0) |

| Fostering relationships/networks | Learning during COVID-19 has made me appreciate the opportunity connect with others, sometimes students and instructors; I have recognized the benefits of casual social interactions on developing a professional network. On a positive note, I feel like I have been growing better relationships with my colleagues and professors despite the remote environment. I have been pushing myself to talk more to people and reach out to professors; this has allowed me to have more 1:1 meetings and get to know my professors and peers better. Four out of my five classes include weekly meetings among our working groups. This has been much more helpful for me to make deeper connections with classmates compared to last semester. I feel like people in my program are actually getting to know me as a person, not just as a student, which is important to me. |

1 (2.1) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0) |

| Benefits of a virtual learning format | However, given the fact that English is not my first language, it has been an advantage to have a recording of every class and have the possibility of watching it again if I didn’t understand something. I enjoy the flexibility remote learning has given me (especially my courses that have been “asynchronous” and I can watch whatever I want) However, I will admit, that it is much less stressful day to day not driving my usual 40 minutes commute each way (and it really saves money on gas). I also have the added benefit of being with my dog pretty much every da Some of the benefits that moving virtual provided was that there was increased flexibility in where I could attend class. It helped cut down on time, since there was no need to travel to SPH. As long as I had internet connection, I could attend class. It opened up many more opportunities to attend various seminars and workshops across the country that I would not have been able to attend. |

7 (14.9) | 2 (4.3) | 5 (10.6) |

| Applicable learning content | I’m loving the content of things I am learning about, and believe they are applicable, especially to the current events happening now. | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.3) |

| Unforeseen health benefits | I go for more walks than I ever have and I also read more than I used to. I feel like my leisure time is spent less in front of tv and phone screens because I’m so worn out from my computer screen. This may be a good thing but I can consciously tell that my walks and reading are to keep me sane and not just because I actually want to do those things more than I used to. | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

Participants were asked to reflect on remote learning experiences in the previous 6 months.

Participants were asked to reflect on remote learning experiences during the previous month.

Perceived Challenges to Remote Learning

Poor mental and emotional health.

Approximately 79% (37/47) of participants reported experiencing poor mental/emotional health challenges from remote learning at time-point one (Table 1). Participants reported having less interest in doing things, illustrated by the following: “I have less interest in stuff, feeling more fatigued, and in general just struggling to find motivation in day-to-day life,” while other participants explicitly described how the pandemic negatively impacted their mental health. Across the study period, poor mental/emotional health impacts persisted with 81% (38/47) and 66% (31/47) of participants at time-points two and three, respectively.

Lack of interactions.

During time-point one, 68% (32/47) of participants reported a lack of interactions from remote learning. Participants said it was difficult to interact with professors and noted how this lack of interaction could impact their careers: “The logistics of learning are challenging. The hardest part is making connections with professors. I find it difficult to make personal connections over online formats like Zoom and e-mail. I am worried this will be detrimental to my career search after graduation, as professors are great contacts to job opportunities/alumni.” Other participants described how more time and effort were required to interact with professors. Additionally, participants described how remote learning negatively impacted their ability to interact with peers and how this directly affected their motivation: “The virtual nature of classes decreased collaboration and social interaction with my classmates which has taken away from my graduate experience and created feelings of isolation. This has had a negative impact on my motivation.” Other participants described a lack of relationships with peers. Although two-thirds of participants reported challenges surrounding lack of interactions during time-point one, the percentage of participants reporting this challenge decreased at time-point two (45%; 21/47). At time-point three, only 25% of participants (12/47) described lack of interaction as a challenge to remote learning.

Learning course content.

Learning course content was a challenge reported by over half of the sample during time-points one (55%; 26/47) and two (53%; 25/47). Participants described challenges to learning course content related to professors not adapting content to fit remote environments: “Challenges that arose in my learning were professors not shifting their content to be engaging for online learning.” Other issues specific to course content were related to the amount of group work assigned to students.

Zoom fatigue.

Nearly 40% (18/47) of participants said Zoom fatigue/anxiety during time-point one, while the percentage of participants decreased slightly throughout the study period (36% (17/47) and 28% (13/47), time-points two and three, respectively). While some participants explicitly named Zoom fatigue: “Zoom fatigue was another major issue I faced. It was difficult to maintain a high-level of class engagement over video.” Others were less explicit, for example: “Due to the pandemic, being online and behind a screen most of the day everyday has made it challenging to focus and be as productive as I normally am.”

Lack of university support.

Across the study period, approximately 13% (6/47) to 19% (9/47) of participants described the lack of university support as a challenge related to remote learning. For example, one participant mentioned: “We are expected to perform at a high quality without receiving high quality education and/or much support from the university.” In addition, other participants described challenges to navigating their MPH program.

Coping with remote learning.

Thirty-four percent (16/47) of participants reported that they engaged in coping mechanisms to address challenges they experienced at time-point one, while 15% (7/47) reported engaging in coping mechanisms at time-points two and three. Some participants described strategies to address challenges, such as spending time outdoors, as illustrated here: “I look at my computer all day for class, then continue my homework and attend all my meetings on my computer. It has made me have to better manage my life outside of school to improve my mental health. I go for more walks than I ever have and read more.” Others described multiple strategies, including going outside for a walk or run, taking breaks from their screen, listening to music, etc. as a way to cope.

Perceived Benefits to Remote Learning

A consistent percentage of participants reported positive benefits to remote learning (Table 1). At time-point one, 28% (13/47) of participants perceived experiencing positive impacts, while 26% (12/47) similarly reported these benefits across time-points two and three. The key perceived benefits of remote learning that emerged from reflections included students: feeling motivated to continue pursuing public health education/career and/or public health opportunities, receiving support from faculty and staff, fostering relationships/networks, benefits from a virtual learning format, applicable learning content, and general health benefits.

Motivated to continue pursuing public health education/career and/or public health opportunities.

One positive impact of remote learning that was described by 8.5% (4/47) [reflection #1], 8.5% (4/47) [reflection #2], and 10.6% (5/47) [reflection #3] of participants was related to feeling motivated to continue pursuing public health education/career or public health opportunities that emerged from the ongoing pandemic. For example, one participant mentioned: “Nonetheless, COVID-19 has definitely increased my desire to enter the Public Health workforce and has also motivated me to acquire/expand my quantitative skills and ability to analyze data by using tools such as GIS and R.” While related to opportunities, another participant described that they were given more job opportunities because of the pandemic, “I have found more ways of how I can be of help during this pandemic and have also been given more job opportunities to do so because of the pandemic.”

Support from faculty and/or staff.

Though less commonly reported by participants in the study, we found that one perceived benefit of the remote learning environment was related to obtaining support from school of public health faculty and/or staff. Although this was not reported by any participants that completed reflection #3 (0%; 0/47), during reflection #1 and #2, at least one participant reported this as a benefit. For example, one participant mentioned: “Fortunately, all professors were open and willing to provide any extra help needed to really understand the course material.” In addition, staff were recognized as supporting students during the pandemic, as illustrated by the following quote: “However, there have been some positive experiences including great support from staff. They’ve really helped motivate myself and others, giving us tools to navigate the rest of the semester. It’s definitely shifted my perspective a bit on the impact of COVID-19 on my personal life and mental health.”

Fostering relationships/networks.

A few participants [2.1% (1/47)–4.3% (2/47)] described that remote learning facilitated better relationships with peers and professors. For example: “On a positive note, I feel like I have been growing better relationships with my colleagues and professors despite the remote environment. I pushed myself to talk more to people and reach out; this has allowed for more 1:1 meetings and to get to know my professors and peers better.” While another participant mentioned that remote learning has allowed them to make deeper connections with classmates.

Benefits of a remote learning format.

One of the most common perceived benefits was related to engaging in a remote learning environment. During reflection #1 we found that nearly 15% (7/47) of participants found that engaging in remote learning resulted in benefits that not only impacted their life as students, but also positively impacted their life outside of school. For example, one participant mentioned how the flexibility of a remote learning environment impacted their personal life: “I love the flexibility of being able to do everything from home, it saves me a lot of travel time and increases the available hours that I have in the day… This remote learning has also allowed me to be able to spend more time with my family. I am a caregiver for my 90-year-old grandpa so I am grateful for the extra time with him. I guess my look at grad school is a little different than most.” In addition, many participants mentioned that the remote learning environment supported them as students, with one participant noting the following: “… given the fact that English is not my first language, it has been an advantage to have a recording of every class and have the possibility of watching it again if I didn’t understand something.” This benefit was reported by 4.3% (2/47) and 10.6% (5/47) of all participants during reflection #2 and #3, respectively.

Applicable learning content.

While not as commonly reported in the study, we found that some participants [2.1% (1/47)–4.3% (2/47), reflections #2 and #3, respectively], found course content to be more applicable because they were living through a pandemic. The quote read as follows: “I’m loving the content of things I am learning about, and believe they are applicable, especially to the current events happening now.”

Health benefits.

Finally, at least one participant reported a perceived health benefit that emerged from engaging in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. During reflection #2, a participant mentioned that they were getting more physical activity than before the pandemic: “I go for more walks than I ever have and I also read more than I used to. I feel like my leisure time is spent less in front of tv and phone screens because I’m so worn out from my computer screen. This may be a good thing but I can consciously tell that my walks and reading are to keep me sane and not just because I actually want to do those things more than I used to.” This benefit however was not reported by participants during reflection #1 or #3.

Thematic Analysis of the Perceived Impact on Career Goals From Remote Learning

During April 2021, when participants were asked to reflect on how remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic affected their career goals in public health, positive and negative alterations were indicated (Table 2). Twenty-six percent (12/47) of participants reported that the pandemic resulted in them being more commitment to their public health career goals, as stated by one participant: “It reinforced my decision and commitment to join the public health workforce and has made me think about work I might be able to get involved in in my future career to support public health efforts to prevent/anticipate future pandemics.” Additionally, 23% (11/47) of participants felt that learning through a pandemic allowed them be more prepared to achieve their career goals: “I think living through this pandemic has given me perspective and provided adversity that made me more equipped to adapt to different circumstances in my career. This will prepare me well for a career in the field of public health despite how tough it has been mentally and collectively as a population.”

Table 2.

Themes and Quotes Representing How Living Through the Pandemic Impacted the Students’ Public Health Career Goals (N = 47).

| Theme | Representative quotes abstracted from reflection # 4 (April 2021) | n (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| More committed to public health goals | I think living through this pandemic has only further motivated me to pursue a career in public health. I knew this field was important before the pandemic, but now the whole world knows how important public health is, and why public health professionals are needed. The pandemic highlighted issues that already exist in our healthcare system: access issues, inequities, improper incentivizing, etc. I’m more motivated to work toward better solutions to these issues after seeing how deeply they impact the lives of patients. It has made more committed to the field while instilling in me a desire to expand beyond my particular MPH focus to include public health communication and infectious disease. However, simultaneously, it has been daunting and at times I feel burned out from the feeling of needing to be an expert in everything. It seems like being concerned with public health matters has overwhelmed both my school life, work life, and personal life, which has made me less enthusiastic about a public health career. It reinforced my decision and commitment to join the public health workforce and has made me think about work I might be able to get involved in in my future career to support public health efforts to prevent/anticipate future pandemics. |

12 (25.5) |

| Halted goals | It has ultimately halted them. It is hard to deal with a pandemic, classes, and applying for jobs. More so, it is discouraging read job descriptions that I am not qualified for as a result of an online university. It is has impacted my mental health, therefore I am taking a step back from my career goals. It has negatively impacted my career goals because sometimes the amount of pushback from people about something as simple as mask wearing makes me feel despondent about this work. Why should I pursue a field that a large majority of the United States thinks is fake? That has made me question my career goals and reevaluate what I want to do with my degree. I am disappointed to admit that it’s made me consider going into industry over public service. After seeing how leaders in my field were disrespected and even threatened (such as Drs. Anthony Fauci and Amy Acton) by people who have no background in the field, it has made me think, well what does this mean for my future? |

6 (12.8) |

| More prepared for reaching goals | I don’t think the pandemic has hindered my career goals in any way. If anything, I gained great insight and experience during a pressing global pandemic which is an asset. Living through a pandemic has given me insight in what steps the public health community should take during a public health crisis. I think that receiving my schooling during a pandemic has given me a unique learning opportunity, that will help me with my future career as an infection preventionist. It’s opened the opportunity to engage with people virtually on a larger scale, which makes collaboration much easier, so I’m excited to use that expansion to my benefit. It’s also given me a healthy dose of awareness of how limiting people’s resources can be which has made me more motivated on changing the system, rather than helping individuals, to be more healthy. I think living through this pandemic has given me perspective and provided adversity that made me more equipped to adapt to different circumstances in my career. This will prepare me well for a career in the field of public health despite how tough it has been mentally and collectively as a population. |

11 (23.4) |

| No change in goals | Still want to be a public health hero. That does not changed and will not change. I do not feel like the pandemic has impacted my career goals, as my desired career path is the same as it was before the pandemic. It has not. My career goals have not changed and I am not worried about opportunities being limited in that due to the pandemic. I don’t think it’s changed my career goals but has definitely made me proud and excited to be in this field to make real change in the world and I hope that people realize how important public health professionals are. |

18 (38.3) |

Themes are not mutually exclusive and may therefore not total 100%.

Of note, 38% (18/47) of participants stated that the pandemic resulted in no change to their career goals, as illustrated by the following: “I don’t think it’s changed my career goals but has definitely made me proud and excited to be in this field to make real change in the world and I hope that people realize how important public health professionals are.” While other participants said that the pandemic halted their goals (13%; 6/47), as illustrated: “I am disappointed to admit that it’s made me consider going into industry over public service. After seeing how leaders in my field were disrespected and even threatened (such as Drs. Anthony Fauci and Amy Acton) by people who have no background in the field, it has made me think, well what does this mean for my future?”

Summary of Participants’ Feelings Regarding Their Public Health Education

When asked to provide a one-sentence quote that summarized participants’ feelings regarding their education at varying points of the academic term, participants most frequently cited the following: (1) exhausted (n = 27); (2) graduate (i.e., meaning wanting to graduate) (n = 25); (3) challenged (n = 21); and (4) excited (n = 21) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of participants’ feelings (reflection #1-#4, Jan-April 2021) regarding their graduate public health education across the Winter 2021 academic semester.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact the higher education landscape. This longitudinal, reflective survey allowed MPH students to reflect on and describe their unique educational experiences as public health trainees during a pandemic and how it shifted their career goals. While many students had concerns about their public health education, many also felt optimistic about their career goals. This study sheds light on how students respond to this changing educational landscape and how it impacts their public health education so that public health instructors can support their learning and career preparation.

One of the main challenges reported by participants included poor mental health. Recent reports of graduate students from other disciplines, such as the biomedical sciences or nursing, provide evidence of similar challenges with psychological well-being during the pandemic (Rosenthal et al., 2021; Staff, 2021). Graduate students are a population that exhibited high levels of stress and anxiety before the pandemic (Allen et al., 2021). However, they are now dealing with new challenges out of their control, such as learning course content virtually or dealing with faculty or staff who may be unengaged (Soria et al., 2020). The added unexpected stressors from remote learning and having to develop coping mechanisms for these new stressors may interfere with learning and career preparation for MPH students.

Although most institutions have now switched back to in-person learning, students now expect the flexible and accessible nature of course materials such as lecture recordings or hybrid options (Supiano, 2022). This new shift in the expectations of students concerning learning modalities has resulted in a loss of students’ assimilation into the classroom environment and their degree programs, leaving students without the typical student-instructor, student-content, and student-student interactions (Zamora et al., 2022). Those social interactions with instructors, for example, are critical for academic success and professional development, such as communication or networking for internship or job prospects (Raposa et al., 2021). As learning modalities continue to shift to being more flexible or virtually accessible, the lack of learning interactions may affect how prepared MPH students feel not only working on core public health content but also interpersonal and other professional skills. The participants in this study made it clear that their inability to interact with peers, course content and instructors consistently or reliably affected their overall development as public health trainees.

Many students in the study reported benefits to their career preparation in public health. The flexibility of the school/workday allowed students to take on hours at jobs more so than if they attended formalized, in-person school activities. An early report from undergraduate and graduate public health students regarding abrupt remote learning at the start of the pandemic similarly indicated that the remote environment allowed for more flexibility in how they spent and managed their daily activities (Armstrong-Mensah et al., 2020). Although this was a reported benefit, recent literature suggests that when students have this flexibility of hybrid learning, they have more difficulties managing their priorities, primarily coursework (Neuwirth et al., 2021). Additionally, being immersed in a real-life public health pandemic permitted students to work directly in the field on tasks related to the pandemic. Engaging in response measures, such as contact tracing, was not unique to this sample but familiar to public health and other allied health professional trainees in the United States (Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health, 2020).

Study Limitations

We used a convenience sampling method to recruit students for the present study, so the sample may not have been representative of the MPH student population at the study institution. Students who joined the study likely had more extreme experiences than others in the program. However, the sample contained students representing all school departments except for one that did not have MPH students during the study period. Previous studies have reported that participants who self-select enrollment in research studies may be related to the fact that participants have more extreme experiences related to either the exposure and/or outcome under study (Lash et al., 2009). The presence of selection bias could ultimately affect the generalizability of findings. The authors posit that students that enrolled in the present study could have enrolled because they had more extreme experiences related to remote learning during the pandemic. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that students enrolled for a variety of other reasons. For example, because they wanted to make extra income via receiving participant compensation fees for completing the study, on the other hand, it is possible that students were simply eager to share their thoughts and experiences. Although the open-ended, written reflections were a strength in allowing participants to share their experiences and feelings (Liu, 2019), not having a perspective methodology may have underestimated thematic analysis percentages.

Conclusions

This work demonstrated mixed perceptions from the forced shift in learning modalities that MPH students had on their learning and career goals in public health. Study findings are relevant to public health educators, and leaders tasked with understanding the impact of future shifts in learning environments on student experiences. These experiences are critical to discuss as the pandemic continues to impact the higher education landscape. Understanding students’ responses can also guide public health instructors to best prepare trainees to join the workforce during the ongoing and future unforeseen public health crises that continue or have the potential to disrupt learning modalities.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The University of Michigan Center for Academic Innovation, Student Academic Innovation Fund provided funding for participant compensation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Allen HK, Barrall AL, Vincent KB, & Arria AM (2021). Stress and burnout among graduate students: Moderation by sleep duration and quality. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(1), 21–28. 10.1007/s12529-020-09867-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alperin M. (2015). Predictors of student success in an online master of public health degree program. https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/alperin_melissa_201512_edd.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-Mensah E, Ramsey-White K, Yankey B, & Self-Brown S (2020). COVID-19 and distance learning: Effects on Georgia State University School of Public Health Students. Public Health Frontier, 8, 576227. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.576227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. (2020, June 11). ASPPH fellows on the frontlines of COVID-19. https://www.aspph.org/aspph-fellows-on-the-frontlines-of-covid-19/

- Boyatzis RE (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development (pp. xvi, 184). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Chhetri C (2020). “I lost track of things”: Student experiences of remote learning in the COVID-19 pandemic [Conference session]. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference on Information Technology Education (pp. 314–319). 10.1145/3368308.3415413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camber M, Henderson D, & Ruelas DM (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on health professions student’s perceptions, future education and career aspirations and confidence in public health responses. Journal of American College Health. Advance on line publication, 10.1080/07448481.2022.2077111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiviniemi MT (2014). Effects of a blended learning approach on student outcomes in a graduate-level public health course. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 47. 10.1186/1472-6920-14-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash TL, Fink AK, & Fox MP (2009). Selection bias. In Lash TL, Fox MP & Fink AK (Eds.), Applying quantitative bias analysis to epidemiologic data (pp. 43–57). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y (2019). Using reflections and questioning to engage and challenge online graduate learners in education. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 14(1), 3. 10.1186/s41039-019-0098-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirth LS, Jović S, & Mukherji BR (2021). Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 27(2), 141–156. 10.1177/1477971420947738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raposa EB, Hagler M, Liu D, & Rhodes JE (2021). Predictors of close faculty-student relationships and mentorship in higher education: Findings from the Gallup-Purdue Index. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1483(1), 36–49. 10.1111/nyas.14342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, Lee S, Jenkins P, Arbet J, Carrington S, Hoon S, Purcell SK, & Nodine P (2021). A survey of Mental Health in graduate nursing students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurse Educator, 46(4), 215–220. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So H-J (2009). Is blended learning a viable option in public health education? A case study of student satisfaction with a blended graduate course. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 15(1), 59–66. 10.1097/01.PHH.0000342945.25833.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria KM, Horgos B, & McAndrew M (2020). Obstacles that may result in delayed degrees for graduate and professional students during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8d46b49s [Google Scholar]

- Staff TPO (2021). Correction: Biomedical graduate student experiences during the COVID-19 university closure. PLoS One, 16(12), e0261553. 10.1371/journal.pone.0261553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supiano B (2022). The attendance conundrum: Students find policies inconsistent and confusing. They have a point. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 68(13), 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Walker ER, Lang DL, Alperin M, Vu M, Barry CM, & Gaydos LM (2021). Comparing student learning, satisfaction, and experiences between hybrid and In-Person course modalities: A comprehensive, mixed-methods evaluation of five public health courses. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 7, 29–37. 10.1177/2373379920963660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick A (2021). Interest in public health degrees jumps in wake of pandemic: Applications rise. The Nation’s Health, 51(6), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wasil AR, Franzen RE, Gillespie S, Steinberg JS, Malhotra T, & DeRubeis RJ (2021). Commonly reported problems and coping strategies during the COVID-19 Crisis: A survey of graduate and professional students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 404. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.598557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolston C (2020). Pandemic darkens postdocs’ work and career hopes. Nature, 585(7824), 309–312. 10.1038/141586-020-02548-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora AN, August E, Fossee E, & Anderson OS (2022). Impact of transitioning to remote learning on student learning interactions and sense of belonging among public health graduate students. Pedagogy in Health Promotion. 10.1177/23733799221101539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]