Abstract

Nineteen Rhizomucor miehei and Rhizomucor pusillus isolates were assayed for their ability to utilize 87 various substrates as a single carbon source. Besides a difference in sucrose utilization, distinctive differences were found in the utilization of glycine, phenylalanine, and β-alanine. Five isoenzyme systems also proved useful for the determination of markers of distinctive value at a species level. Data were used to obtain information about the genetic polymorphism of these species: a high degree of variability was found among the R. pusillus isolates, whereas the group of R. miehei isolates was more homogeneous genetically.

The zygomycoses comprise a diverse group of rare mycotic diseases; the term mucormycoses is preferred for zygomycoses caused by some members of the order Mucorales (e.g., Absidia, Rhizomucor, Rhizopus, and Mortierella [7, 10]). These infections are most frequently associated with diabetic ketoacidosis, immunosuppressive conditions, extreme malnutrition, or neutropenia (7). Though these mycoses are relatively rare, they attract special attention, as they are rapidly progressive and frequently fatal (12, 14).

The genus Rhizomucor includes three species: Rhizomucor pusillus, Rhizomucor miehei, and Rhizomucor tauricus; these are clearly distinct from Mucor by virtue of their thermophilic nature and some morphological features (8). While the legitimacy of regarding R. tauricus as an autonomous species (represented by a single isolate only) is sometimes questioned, the other two Rhizomucor species are well represented in nature (8).

Fungi belonging in this genus are found among the etiological agents of human and animal mucormycosis. The role of R. tauricus in such infections is unknown, but there are both clinical and experimental data concerning infections caused by R. pusillus or R. miehei (7, 11). However, there are two reasons why the exact number of infections caused by one or another of the Rhizomucor species can only be guessed at. One is that in several cases the fungal pathogen has not been identified properly at low taxonomic levels (genus and species), and the other is that there is some uncertainty in the differentiation of R. miehei and R. pusillus isolates. Though R. miehei has been found to be homothallic, while R. pusillus is mainly heterothallic, the discovery of the rarely occurring homothallic R. pusillus isolates did not help to simplify the scheme (8). Certain approaches, such as determination of the number of nuclei in the sporangiospores (15) or mating studies coupled with determination of the morphological traits of the zygospores (8, 18), could supply characteristics for the delimitation of these species. However, the differences are not clear-cut in every case (15), or the procedure requires a prolonged time (8).

Both isoenzyme analysis and the determination of carbon source utilization patterns have proved to be valuable tools in the handling of taxonomic questions in the genus Mucor (16, 17). Analysis of proteases by immunoelectrophoretic techniques underlined the connection of the homo- and heterothallic strains of R. pusillus and their difference from R. miehei (2). Assimilation abilities on a limited number of compounds have also been checked: the growth-stimulative effect of thiamine and the inability to assimilate sucrose were found to be characteristic of R. miehei (10, 11), although these differences seem to be insufficient to allow species delineation in every case. These characteristics, together with the colony color (brownish for R. pusillus and grayish for R. miehei) and the sizes of the zygospores (the diameter is below 50 μm for R. miehei and over 50 μm for R. pusillus), are now used to identify Rhizomucor isolates (8, 11).

The purpose of the present study was to broaden the basis of knowledge, affording a methodically simple, quick, and more unambiguous identification of the two Rhizomucor species. As part of this, carbon source assimilation patterns were determined and isoenzyme analysis was carried out with 19 Rhizomucor strains obtained from various sources and three other zygomycetous strains (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Fungal strains investigated in the present study

| Species name | Codea | Original codeb | Source and other codec |

|---|---|---|---|

| R. pusillusd | R2A | NRRL 2543 | Animal mycosis, United Kingdom; ATCC 22064 as R. miehei |

| R. pusillusd | R2B | NRRL 2543 | Animal mycosis, United Kingdom; ATCC 22064 as R. miehei |

| R. pusillus | R4 | NRRL A-23448 | US |

| R. pusillus | R5 | NRRL A-23504 | US |

| R. miehei | R6 | NRRL 3169 | US, United States; ATCC 46343 |

| R. miehei | R8 | NRRL 5282 | Composted peppermint hay, India; ATCC 46344 |

| R. miehei | R9 | CBS 370.71 | Human sputum, The Netherlands |

| R. miehei | R10 | NRRL 5284 | Rotting apple, United States; ATCC 46346 |

| R. miehei | R11 | NRRL 5901 | Cow placenta, United States |

| R. miehei | R12 | NRRL 6303 | Corn crop, United States; A-16207 |

| R. pusillusd | R13 | NRRL A-13100 | US |

| R. miehei | R14 | NRRL A-18359 | US |

| R. miehei | R15 | CBS 360.92 | Human mycosis, Australia |

| R. pusillusd | R16 | ETH M4920 | Human tracheal discharge, Switzerland |

| R. miehei | R17 | ETH M4918 | Composted litter, Switzerland |

| R. pusillus | R18 | WRL CN(M)231 | Suspected pathogen from lamb |

| R. pusillus | R19 | FRR 2490 | US, Australia |

| R. pusillus | R20 | IBP M.p./1 | US, Poland |

| R. pusillusd | R21 | FRR 1652 | US |

| Absidia glauca | Ab1 | CCM F450 | Soil; NCAIM F00658 |

| Mucor piriformis | N6 | NRRL 26212 | Rotting pear, United States |

| Rhizopus stolonifer | Rp11 | SzMC 1123 | Soil, United States |

A code which is used throughout this paper for clarity.

CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands; ETH, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Culture Collection, Zurich, Switzerland; FRR, CSIRO Food Research Culture Collection, North Ryde, New South Wales, Australia; IBP, Institute of Fermentation Industry Culture Collection, Warsaw, Poland; SzMC, Szeged Microbial Collection, University of Szeged, Szeged, Hungary; WRL, Wellcome Bacterial Collection, Beckenham, United Kingdom.

US, unknown source.

Isolate whose original species name was found to be incorrect.

The abilities of the Rhizomucor and selected Absidia, Mucor, and Rhizopus strains to utilize 87 individual compounds as their sole carbon source were tested basically as described earlier for Mucor isolates (16), except that the incubation was at 37°C (20°C for Mucor).

Of the 87 carbon substrates tested, 13 yielded uniformly positive results; these included d-lyxose, l-xylose, maltose, lactose, melibiose, starch, sorbitol, l-alanine, l-proline, l-tyrosine, l-asparagine, raffinose, and glycerol-α-monoacetate. Thirteen other compounds gave only negative results; these were xylan, γ-butyrolactone, vanillin, α-methyl-d-xyloside, ascorbic acid, l-glutamine, l-malic acid, methanol, orotic acid, l-lysine, protocatechuic acid, inulin, and gallic acid. Certain carbon substrates led to ambiguous results with low reproducibility. These were l-rhamnose, l-isoleucine, l-serine, cytosine, thymine, dihydroxyacetone, α-methyl-d-galactoside, d-glucosamine, fumaric acid, succinic acid, gluconic acid, l-ornithine, and uracil.

The remaining 48 carbon substrates were found to be utilized to various extents by the investigated strains (Table 2). Most of these variations were intergeneric and related to the differences observed between Rhizomucor, Absidia, Mucor, and Rhizopus strains. Among them, however, four compounds whose utilization showed a clear difference between the R. miehei and R. pusillus isolates were identified. These were sucrose, glycine, phenylalanine, and β-alanine; this is the first example of the distinctive value as biochemical markers of the last three of these. The difference in sucrose utilization was described earlier (10); this and the stimulative effect of thiamine on the growth of R. miehei were the only two biochemical markers of some practical value for the differentiation of these species (11). The use of these four carbon sources allows a clear delineation of these two species.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of growth on carbon sources variably used by zygomycetous strainsa

| Compound | R. miehei | R. pusillus | Rhizopus (Rp11) | Absidia (Ab1) | Mucor (−4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-Ribose | ++ | ++ | (−) | + | − |

| d-Arabinose | + | + | − | (−) | − |

| d-Xylose | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | + (i) |

| d-Glucose | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| d-Mannose | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| d-Galactose | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| d-Fructose | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| l-Arabinose | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| l-Sorbose | (−) | (+) | − | (+) | + |

| Sucrose | − | + | − | +++ | − |

| Cellobiose | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| Melezitose | (−) | (−) | − | + | + |

| Dextran | + | + | − | − | (−) |

| Glycerol | (−) | + | + | (+) | − |

| i-Erythritol | (−) | + | − | − | (−) |

| d-Mannitol | ++ | + | + | ++ | + |

| Galactitol | (−) | − | − | (+) | (−) |

| Ribitol | + | + | (−) | +++ | (+) |

| myo-Inositol | (+) | (−) | − | − | (−) |

| Xylitol | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| Glycine | − | + | + | + | (−) |

| l-Valine | (+) | + | − (i) | (+) | (−) |

| l-Leucine | − | − | − | + | (−) |

| l-Methionine | (−) | − | − (i) | − | (−) |

| l-Phenylalanine | − | + | (−) | (+) | (−) |

| l-Tryptophan | − | − | − | − | (−) |

| l-Threonine | (−) | (−) | − | (−) | − |

| l-Cysteine | (+) | (−) | − | (−) | (−) |

| l-Aspartic acid | ++ | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| l-Glutamic acid | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | + |

| l-Arginine | −, + | + | (−) | + | (−) |

| l-Histidine | (−) (i) | − | − (i) | + | − |

| β-Alanine | − | + | − | (+) | (−) |

| l-Citrulline | − | (−), + | (+) | (+) | (−) |

| Uridine | − | (+), − | − | − | − |

| Cytidine | − | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Adenosine | (−) | (+) | (−) | + | + |

| l-Lactic acid | − | −, (+) | (−) | − | + |

| l-Hydroxybutyric acid | − | (−), + | − | − | (+) |

| β-Methyl-d-galactoside | +, (+) | ++ | − | − | (+) |

| α-Methyl-d-mannoside | − (i), + | − (i), + | − | − | (+) |

| 5-Keto-d-gluconic acid | −, (+) | + | − | − | (+) |

| 2-Keto-d-gluconic acid | (−), + | + | − | + | (−) |

| Gentisic acid | −, + | + | − | − | − |

| d-Glucuronic acid | −, + | −, + | − | − | − |

| d-l-Isocitric acid | − | −, + | + | + | − |

| Pyruvic acid | (+), + | (−), + | (+) | + | (−) |

| β-Methyl-d-glucoside | −, (−) | −, (−) | − | (−) | − |

Growth for a particular strain is designated on the basis of the strength of colony development as follows: +++, vigorous growth; ++, average growth; +, slight growth [very weak mycelial growth was designated (+) or (−) if it suggested an ambiguous slight growth or an ambiguous lack of growth, respectively]; −, no growth; (i), inhibition of spore germination or reduced (compact) colony morphology.

To provide further characteristics of distinctive value, isoenzyme analysis of the isolates was also carried out. Sporangiospores collected from malt extract agar slants incubated at 37°C for 5 days were inoculated (107 spores/150 ml) in yeast extract-glucose liquid medium. Cultivation was carried out in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks at 37°C on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. Protein extraction and electrophoresis were performed as described earlier (17). The resolvable enzyme systems used were acid phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1) (4), β-esterase (EST) (EC 3.1.1.2) (4), glutamate dehydrogenase (EC 1.4.1.4) (1), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6D) (EC 1.1.1.49) (5), and malate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.38) (3). All incubations took place at 21°C, in the dark. The gels were then rinsed, first in distilled water and next in 7% acetic acid, and read.

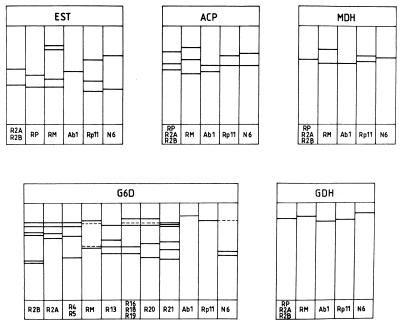

The highest variability was found for G6D; eight different electrophoretic patterns (electromorphs) were detected, while for EST three electromorphs were found. The least variable were the acid phosphatase, glutamate dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase staining patterns; these each showed two different electromorphs. These two electrophoretic patterns correlated perfectly with the two investigated Rhizomucor species. A similar correlation was found in the case of the EST pattern; however, this is less easily scored because of the more complex pattern of this activity stain (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Isoenzyme patterns observed for various Rhizomucor, Absidia, Rhizopus, and Mucor isolates. The direction of migration is towards the anode. RP, heterothallic R. pusillus strains; RM, R. miehei strains. For other strain codes, see Table 1.

This study was started with 18 different Rhizomucor strains. However, after preliminary experiments, it turned out that the strain NRRL 2543 (isolated from an animal mycosis) is not homogeneous; it contains two morphologically slightly different fungi. Otherwise, this strain clearly illustrates the problems with the species identification in the genus; it is maintained under different names in two international collections (as R. pusillus in the Northern Regional Research Laboratory Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, Peoria, Ill. [NRRL], and as R. miehei in the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. [ATCC]). On the basis of our results, it was identified as R. pusillus. While the carbon source assimilation patterns of these separated strains were the same, their G6D patterns were different.

Besides determining easily countable characteristics for the identification of Rhizomucor isolates, the experimental data provide preliminary information concerning the genetic variability of these species. After enzyme staining, each independent band with a defined relative mobility was coded with a binary state character; this was 1 if the band was present and 0 if the band was absent for an isolate (variations in staining intensity were not taken into account). The results of the carbon source utilization experiments were coded as follows: 0, negative; 0.5, weak, ambiguous reaction; 1, positive reaction. Matrices created from these data were used for the calculation of Jaccard coefficients. Dendrograms were produced with an unweighted pair-group method by using arithmetic averages (UPGMA) (13) linkage. All computations were performed with the SYNTAX 5.0 software package (6).

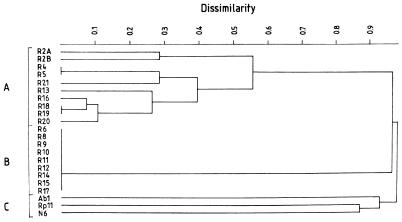

There was no basic difference between the dendrograms created from the unified data matrix or from the matrix of carbon source utilization data (results not shown) and those created from the isoenzyme data alone (Fig. 2). All these dendrograms revealed the presence of three clusters. One of these (cluster C) corresponds to the isolates used as outgroups in this study (Ab1, N6, and Rp11), while clusters A and B contain the investigated R. pusillus and R. miehei isolates, respectively (Fig. 2). While the reading of the extent of colony growth inevitably involves some inconsistencies (resulting in a higher variation of characteristics), the evaluation of isoenzyme patterns is less problematic. Therefore, we suggest that this discloses the intraspecific variability of R. miehei and R. pusillus more precisely than the other two dendrograms. Three important features could be observed in this dendrogram. First, all R. pusillus isolates segregate from the R. miehei isolates at a very high level of dissimilarity (D = 0.90); this is practically the same as the level of dissimilarity found for the representatives of the other three genera involved in the outgroup (Absidia, Mucor, and Rhizopus; D = 0.87, 0.89, and 0.92, respectively). The second feature is that the extent of genetic polymorphism is different in the two Rhizomucor species: while substantial polymorphism was found among the R. pusillus strains, the investigated R. miehei strains proved to be homogeneous; no difference was revealed with the five enzyme systems investigated. One explanation could be that this phenomenon is connected with the different, homothallic and (mainly) heterothallic natures of R. miehei and R. pusillus, respectively. In this respect, it would be interesting to examine if there is any difference in genetic variability in the homo- and heterothallic R. pusillus strains. Unfortunately, homothallic R. pusillus strains are rare; e.g., of the strains investigated, only R2A and R2B (of common origin) were found to be homothallic. This number of strains is too limited to provide a basis for any conclusion about their different genetic variability. However, as a third observation, it could be seen that the homo- and heterothallic R. pusillus strains segregate into two subclusters at a rather high level (D = 0.56). This clustering is caused by their different EST and G6D patterns. Further investigations, with the involvement of more R. pusillus isolates, should be performed to clarify the background of this high degree of intraspecific polymorphism and its connection (if any) with the sexual characteristic.

FIG. 2.

UPGMA dendrogram of the Rhizomucor and outgroup strains produced by UPGMA linkage of the Jaccard coefficients. It was based on the 57 characteristics obtained from their isoenzyme analysis. The scale represents dissimilarity (squared distance). The cophenetic correlation was 0.9975. The labels A, B, and C mark clusters containing the R. pusillus, the R. miehei, and the outgroup strains, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kerry O’Donnell (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Peoria, Ill.) for providing some of the Rhizomucor strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anné J, Peberdy J F. Characterisation of interspecific hybrids between Penicillium chrysogenum and P. roqueforti by iso-enzyme analysis. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1981;77:401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branner-Jørgensen S, Nielsen R I. Abstracts of the 2nd International Symposium of Genetics of Industrial Microorganisms, Sheffield, United Kingdom. 1974. Comparative enzyme patterns in Mucor miehei Cooney & Emerson and Mucor pusillus Lindt; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer G J. An introduction to isoenzyme techniques. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris H, Hopkinson D A. Handbook of isoenzyme analysis in human genetics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulvey M, Vrijenhoek R C. Genetic variation among laboratory strains of the planorbid snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Biochem Genet. 1981;19:1169–1182. doi: 10.1007/BF00484572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podani J. SYN-TAX. Computer programs for multivariate data analysis in ecology and systematics. Version 5.0. User’s guide. Budapest, Hungary: Scientia Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rippon J W. Medical mycology. The pathogenic fungi and the pathogenic actinomycetes. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 1974. Mucormycosis; pp. 430–447. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schipper M A A. On the genera Rhizomucor and Parasitella. Stud Mycol. 1978;17:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schipper M A A, Stalpers J A. Various aspects of the mating system in Mucorales. Persoonia. 1980;11:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholer H J, Müller E. Beziehungen zwischen biochemischer Leistung und Morphologie bei Pilzen aus der Familie der Mucoraceen. Pathol Microbiol. 1966;29:730–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholer H J, Müller E, Schipper M A A. Mucorales. In: Howard D H, editor. Fungi pathogenic for humans and animals, part A. Biology. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1983. pp. 9–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smitherman K O, Peacock J E., Jr Infectious emergencies in patients with diabetes mellitus. Med Clin N Am. 1995;79:53–77. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman and Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 14.St.-Germain G, Robert A, Ishak M, Tremblay C, Claveau S. Infection due to Rhizomucor pusillus: report of four cases in patients with leukemia and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:640–645. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tansey M R, Kamel S M, Shamsai R. The number of nuclei in sporangiospores of Rhizomucor species: taxonomic and biological significance. Mycologia. 1984;76:1089–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vágvölgyi C, Magyar K, Papp T, Palágyi Z, Ferenczy L, Nagy Á. Value of substrate utilization data for characterization of Mucor isolates. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:613–615. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vágvölgyi C, Papp T, Palágyi Z, Michailides T J. Isozyme variation among isolates of Mucor piriformis. Mycologia. 1996;88:602–607. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weitzman I, Whittier S, McKitrick J C, Della-Latta P. Zygospores: the last word in identification of rare or atypical zygomycetes isolated from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:781–783. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.781-783.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]