Abstract

Norovirus, a positive-stranded RNA virus, is one of the leading causes of acute gastroenteritis among all age groups worldwide. The neurological manifestations of norovirus are underrecognized, but several wide-spectrum neurological manifestations have been reported among infected individuals in the last few years. Our objective was to summarize the features of norovirus-associated neurological disorders based on the available literature. We used the existing PRISMA consensus statement. Data were collected from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Scopus databases up to Jan 30, 2023, using pre‐specified searching strategies. Twenty-one articles were selected for the qualitative synthesis. Among these, seven hundred and seventy-four patients with norovirus-associated neurological manifestations were reported. Most cases were seizure episodes, infection-induced encephalopathy, and immune-driven disorders. However, only a few studies have addressed the pathogenesis of norovirus-related neurological complications. The pathogenesis of these manifestations may be mediated by either neurotropism or aberrant immune-mediated injury, or both, depending on the affected system. Our review could help clinicians to recognize these neurological manifestations better and earlier while deepening the understanding of the pathogenesis of this viral infection.

Keywords: Norovirus, Clinical manifestations, Seizures, Norovirus-associated neurological disorders

Introduction

A relatively less known non-enveloped, positive-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Caliciviridae family, norovirus, also known as Norwalk virus, has been considered a potential human foodborne human enteric pathogen since the 1968 outbreak at an elementary school in Norwalk, Ohio (Adler and Zickl 1969; Kapikian et al. 1972). The family comprises five genera, mainly norovirus, sapovirus , lagovirus, nebovirus, and vesivirus. RNA viral particles were confirmed in stool specimens during that outbreak (Kapikian et al. 1972; Robilotti et al. 2015). Initially, the infected individuals manifested nausea, vomiting, low-grade fever, abdominal cramp, lethargy, and, most importantly, severe diarrhea (Adler and Zickl 1969). Since then, worldwide infected cases have been estimated to be around 685 million, among which approximately 200 million infected pediatric cases have been documented (Patel et al. 2008). Substantial morbidity across a wide range of healthcare settings is noted and predominantly among children, estimated to be around 50,000 deaths per year (Patel et al. 2008; Widdowson et al. 2005).

Clinical features of norovirus infection are nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, and mild self-limited non-bloody diarrhea. Notably, the phrase “stomach flu” was initially used for infected individuals with a low fever and abdominal pain (Kapikian et al. 1972; Robilotti et al. 2015). However, a severe form of this infection is linked to copious diarrhea, which can result in dehydration and occasional death (Kapikian et al. 1972; Robilotti et al. 2015).

Several factors enhance the transmissibility of norovirus, like small inoculums, prolonged viral shedding, and its ability to survive harsh environments (Robilotti et al. 2015). The genome of norovirus consists of a 7.6-kb RNA with a covalent linkage to viral protein genome (VPG) at 5′ and polyadenylated at 3′ ends, consisting of mainly three open reading frames (ORFs), namely ORF-1, ORF-2, and ORF-3 (Jiang et al. 1993; Thorne et al. 2014). Initially, the translational mechanism of ORF-1 produces a large polyprotein complex cleaved by virus-encoded protease during co- and post-translation. The cleavage products include mature nonstructural (NS) proteins (Sosnovtsev et al. 2006); NS6, NTPase/RNA helicase (NS3), RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase (RdRp) (NS7), Vpg (NS5), NS4, NS2 and NS1(Sosnovtsev et al. 2006; Hyde and Mackenzie 2010). ORF-2 and ORF-3 encode the virion’s major and minor structural components, namely VP1 and VP (Herbert et al. 1997). The most significant causative genotype of human noroviral infections is GII (GII.4), followed by GI and GIV (Noel et al. 1999; Lindesmith et al. 2008). Norwalk virus-derived virus-like-particles (VLPs) bind to H antigens in vitro and can hemagglutinate type A, AB, and O red blood cells (Harrington et al. 2002; Hutson et al. 2003). These viral particles can bind to gastroduodenal epithelial mucosal cells (Marionneau et al. 2002). Notably, GII.4 VLPs bind strongly to the saliva of secretor-positive individuals regardless of blood grouping (Frenck et al. 2012). Besides, binding to human Caco-2 intestinal cells by GII.6 norovirus-VLPs is independent of histo blood group antigen (Murakami et al. 2013), whereas the binding depends on cellular maturity as similar to GII.4 strain (Harrington et al. 2004).

Noroviruses can infect brain endothelial cells and increase the expression of matrix metalloproteinases, decreasing the expression of tight junctional proteins and increasing blood–brain barrier permeability (Al-Obaidi et al. 2018). Several wide-spectrum neurological manifestations have been reported among infected individuals in recent years. Our objective was to summarize the norovirus-associated neurological manifestations based on the available literature.

Methods

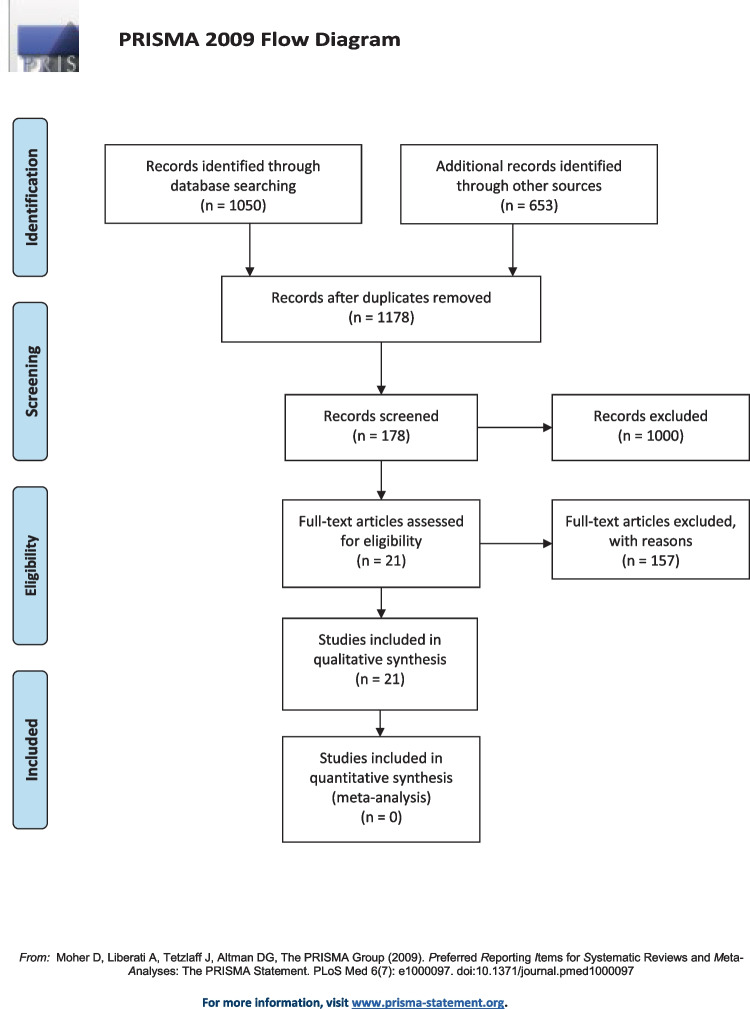

This review followed the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) consensus statement-PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022345256. Studies concerning cases of norovirus infection with confirmed or suspected neurological manifestations were included.

Search strategy

We searched through PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Noro Net databases, which concluded on Jan 30, 2023, using pre-specified search strategies for each database. The search strategy consisted of keywords of relevant medical subject headings and keywords, including “norovirus,” “Caliciviridae,” “demyelination,” “encephalopathy,” “encephalitis,” “enteric nervous system,” “benign convulsions,” “meningitis,” “meningoencephalitis,” “leptomeningitis,” “cerebritis,” and “brain stem involvement.” Sapovirus and vesivirus were also included in our search strategy to capture related articles. We also hand-searched additional norovirus-specific databases using the reference list of the selected studies, relevant journal websites, and renowned preprint servers (medRxiv, bioRxiv, pre-prints.org, and Calcinet) from 2005 to Jan 30, 2023. To decrease publication bias, we invigilated the references of all studies potentially missed in the electrical search. Content experts also searched the gray literature of any relevant articles.

Study selection criteria

All peer-reviewed, preprint (not-peer-reviewed), including cohorts, clinical series, case–control studies, and case reports that met the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, were included in this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) studies reporting patients infected with norovirus with or suspected neurological manifestations, (2) studies registering neurological manifestations of norovirus patients, and (3) parallel studies that analyzed the distribution and incidence of neurological disorders in similar Caliciviridae infections, i.e., sapovirus and vesivirus. Only studies that were published in English were considered. Accordingly, we excluded the studies with the following criteria: (1) prior history of neurological disorders; (2) insufficient data and, subsequently, failure to contact the authors; (3) non‐clinical research, animal studies and reviews, correspondence, viewpoints, editorials, and commentaries; and (4) duplicate publications. The references of the original articles and reviews identified were manually searched further for any article that had been missed out.

Study selection and evidence synthesis

Before the screening process, teams of three reviewers participated in calibration and screening exercises. One reviewer independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified citations, and the remaining two verified those and screened papers. One of the other reviewers then retrieved and screened independently the full texts of all citations deemed eligible by the reviewer on the team and analyzed those data. Another reviewer independently verified these extracted full texts for eligibility for analysis and designed the overall study structure. The corresponding and senior author (JBL) resolved disagreements whenever necessary and took final decisions regarding the study. Throughout the screening and data extraction process, the reviewers used piloted forms. In addition to the relevant clinical data, the reviewers also extracted data on the following characteristics: study characteristics (i.e., study identifier, study design, setting, and timeframe); population characteristics; comparator characteristics, outcomes (qualitative and quantitative); clinical factors (definition and measurement methods), measures of association (relative risks, odds ratios, and hazard ratios), reported funding sources and conflict of interests, and study limitations. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used to evaluate the study’s selection procedure, comparability, and outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Unit discordance among variables was resolved by converting the variables to a standard unit of measurement. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant but could not be calculated due to insufficient data. A meta-analysis was planned to analyze the association of the demographic findings, symptoms, biochemical and neuroimaging parameters, and outcomes. Still, it was later omitted due to the limited availability of comparable data and significant variability among the included studies.

Ethics

This review was based on the available literature on neurological manifestations among norovirus-infected individuals across all age groups; no animal or human subjects were involved. Henceforth, approval from the ethics committee was not applicable.

Results

The selection procedure was carried out according to the PRISMA consensus statement in Fig. 1. Twenty-one articles were selected for the qualitative synthesis. Among these, seven hundred and seventy-four patients with norovirus-associated neurological manifestations were reported, mainly seizure episodes, infection-induced encephalopathy, and immune-driven disorders (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological spectrum of norovirus-associated neurological manifestations

| Authors | Age and sex | Norovirus detection | General Symptoms | Neurological picture | Cerebrospinal fluid parameters | Blood parameters | Neurological evaluation | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kimura et al. (2010) | 60-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Abdominal pain and mild fever before admission, severe diarrhea | Dull consciousness, nuchal stiffness, bradykinesia without rigidity/paresis, apathy, motor aphasia, and gait disturbances | Cell count 25/mm3; protein 130 mg/dl; glucose 69 mg/dl; IgG index 0.63 | Normal | High signal intensity in the opercular cortex and insular part of the left frontal lobe in the FLAIR sequence. Slow waves without spike on electroencephalography | Encephalopathy/encephalitis | Intravenous methylprednisone, immunoglobulins, and acyclovir | Full recovery |

| Eltayeb and Crowley (2012) | 46-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Episodes of vomiting and diarrhea for 36 h following admission | Progressive ascending weakness with hyporeflexia, numbness, and mild facial weakness with deteriorating respiratory failure, and autonomic dysfunction | Cytoalbumin dissociation | Not reported | Neurophysiological studies were consistent with acquired demyelinating polyneuropathy supporting Guillain–Barre syndrome-related changes | Guillain–Barre syndrome | Intravenous immunoglobulins | Good recovery |

| Shimizu and Tokuda (2012) | 28-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample and stool culture | Episodes of vomiting and diarrhea | Blurred vision, ataxic gait, pins and needle-like sensations in hands bilaterally, progressive ascending weakness, upward and downward gaze impairment, hyporeflexia, and absent deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the upper limbs | Cytoalbumin dissociation. Anti-GQ1b antibodies were positive | Not reported | Normal brain and spinal magnetic resonance imaging | Miller Fisher syndrome | Intravenous immunoglobulins | Full recovery |

| Obinata et al. (2010) | 1.3-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of stool and blood samples | Frequent vomiting, mild dehydration, increased heart rate, and respiratory rate | Recurrent generalized seizures, increased muscle tone in her limbs, sluggish light reflex, and no response to painful stimuli | Elevated concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6, interleukin-10, interferon-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α | Leukocytosis, moderately elevated liver enzymes, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase | Diffusion-weighted imaging showed high intensity in the right occipital cortex and, on the following day, expanded up to the subcortical white matter of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes. Electroencephalography findings showed slow waves without paroxysmal discharges | Encephalopathy | Intravenous immunoglobulins, a single course of steroid pulse therapy, and brain hypothermia | Follow-up at two years showed severe mental delay, tonic seizures, and regression in motor development |

| Medici et al. (2010) | 1.3-yr-old male | Norovirus-specific polymerase through a nested reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in stool, plasma, and serum | Increased irritability and gastroenteritis | Afebrile convulsions with tonic–clonic fits | Protein 1400 mg/dl, glucose 55 mg/dl, chlorides 121 mmol/l, and leukocytes 6/mm3 | Normal | Normal brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. No significant changes in electroencephalography | Seizures | Intravenous fluid therapy, acyclovir, and ceftriaxone | Full recovery |

| Chung et al. (2017) | 2-yr-old female | Multiplex polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Diarrhea, fever, and rashes on skin and mouth | Ataxia with gait disturbances, hyperirritability with poor cooperativeness, decreased speech with mild developmental language delay, and weakness in lower limbs with normal deep tendon reflex and absence of Babniski reflex | Cell count 2/mm3, protein 21.6 mg/dl, and glucose 58 mg/dl | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 9 mm/h, C-reactive protein 0.48 mg/l, and differential count 53.1% lymphocytes and 37.1% neutrophils | Asymmetric high T2 signal intensity with leptomeningeal enhancement in the right cerebellar folia suggesting acute cerebellitis | Norovirus-associated cerebellitis | Intravenous methylprednisone pulse therapy for three days and oral prednisone for 3 days | Full recovery |

| Tantillo et al. (2021) | 1.1-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of stool samples | Fever, lethargy with profuse watery diarrhea for the past 2 days | Hemi-clonic movements of left upper and lower limbs, which soon progressed in the state of unresponsiveness, tonic high deviation with bilateral direction-changing horizontal nystagmus | Cell count ~ 1/mm3, protein 22 mg/dl, and glucose 86 mg/dl | Hypernatremia with leukocytosis, lactate 136.8 mg/dl, and blood urea nitrogen 60 mg/dl | Reversible diffusion restrictions. Electroencephalography showed high voltage rhythmic delta activities with multifocal sharp wave complexes | Encephalopathy with status epilepticus | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ito et al. (2006) | 1.9-yr-old female | Electron microscopic picture of stool, and a nested reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of cerebrospinal fluid, stool, and serum samples | Recurrent vomiting and fever | Babinski sign, slow pupillary light reflex, and slightly increased muscle tone | Leukocytes 4/mm3, protein 16 mg/dl, and glucose 183.6 mg/dl | Normal | Normal brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Electroencephalography showed high-voltage slow waves without paroxysmal discharges | Encephalopathy | Acyclovir, dexamethasone, and glycerol | Good recovery |

| Bartolini et al. (2011) | 8-yr-old male | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Nausea, headache, and vomiting | Complex partial seizures with visual hallucinations, trismus, and clonic contractions of the right arm | Normal | Elevated C-reactive protein levels | Magnetic resonance imaging showed bi-parietal cortico-subcortical vasogenic edema | Benign infantile seizure | Ceftriaxone and acyclovir | Good recovery |

| Sánchez-Fauquier, et al. (2015) | 2-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of stool and cerebrospinal fluid samples | Vomiting with diarrhea | Admitted with status epilepticus, episodes of generalized tonic–clonic seizures with choreoathetosis movements predominantly in the head and upper limbs with dyskinetic lingual movements | Elevated cerebrospinal neopterin level with normal biopterin | Metabolic acidosis | Normal computed tomography. Electroencephalography showed slow and disorganized cerebral activity | Viral encephalitis | Valproate, midazolam, levetiracetam, phenytoin, and propofol | Discharged with valproate |

| Yoo et al. (2023) | 7-yr-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Diplopia with impaired vision, pain abdomen with enteritis | Eye movement disorder, mild neck stiffness for the last 5 days, and transient ataxia with bilateral periorbital pain. Bilateral papilledema | Autoantibody panel (anti-MOG, anti NF, AQP4) revealed normal findings | Not reported | Normal brain magnetic resonance imaging and angiography | Norovirus-induced sixth cranial nerve palsy | Intravenous methylprednisone, followed by dexamethasone. Subsequently, intravenous immunoglobulins methylprednisone and acetazolamide | Full recovery |

| 8-mths-old female | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Fever with vomiting for the past 2 days with diarrhea | Status epilepticus | Not reported | Hypernatremia, hyperammonemia, leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis |

High signal intensity with enhancement along the cerebral hemisphere sulci in FLAIR sequences, diffusion restriction in the posterior parietal and occipital cortex, and subcortex on diffusion-weighted imaging Continuous electroencephalography revealed suppressed pattern activities with continuous right central spike discharge at 3–5-s intervals |

Norovirus-induced meningoencephalitis with concomitant disseminated intravascular coagulation | Vancomycin, acyclovir, intravenous immunoglobulins for 3 days, hydrocortisone, and dopamine | Death due to intractable cerebral edema and disseminated intravascular coagulation | |

| Saran et al. (2019) | 45-yr-old male | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Several episodes of loose stools followed by non-bilious and non-projectile vomiting | Weakness hypotonia and hyporeflexia in all four limbs | Cell count within normal limit, protein 60 mg/dl, and glucose 100 mg/dl | Hypertransaminasemia, elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, and leukocytosis | Bilateral cerebral hemispheric hyperintense lesions in the white matter and the pons in T2 and T2-FLAIR weighted imaging. Susceptibility-weighted imaging showed multiple microhemorrhages in the bilateral cerebral hemispheres | Norovirus-induced transient myelin sheath edema |

Steroids and globulins |

Full recovery |

| Nakakubo et al. (2016) | 6-yr-old male | Detection of norovirus antigen in stool | Episodes of vomiting | Mild right foot dysmetria on heel-to-shin test | Not reported | Positivity for anticardiolipin IgG antibodies | T2 and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a high-intensity area of the cerebellum (acute stroke). Magnetic resonance angiography showed no right vertebral artery occlusion on admission. Right vertebral artery occlusion was observed 6 months later | Norovirus-induced cerebellar infarction associated with antiphospholipid syndrome | Aspirin and cilostazol | Full recovery |

| Gutierrez-Camus et al. (2022) | 2-day-old female | A multiplex polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Abnormal movements of limbs and face | Episodes of generalized tonic–clonic seizure with facial grimaces | Not reported | Normal | Diffusion-weighted imaging revealed scattered lesions with restricted diffusions throughout the subcortical and deep white matter. Susceptibility-weighted imaging revealed hemorrhagic changes. Electroencephalography revealed seizure-like electrical changes | Norovirus-associated white matter injury | Symptomatic management | Full recovery |

| Chen et al. (2009) | (15–21 months)/11 males and 8 females | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Fever, mild dehydration, vomiting, diarrhea | Generalized tonic–clonic seizures | Three patients had a lumbar puncture performed, and the cerebrospinal fluid had normal cell counts, glucose, and protein levels | Normal in all patients except one with hypoglycemia | Fourteen patients had computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging performed with normal results, except one. Eleven patients had interictal electroencephalography, which was normal or only showed non-specific sharp waves | Afebrile seizure | Seven received loading doses of phenytoin or phenobarbitone. Two received antiepileptic drug prophylaxis | Full recovery |

| Hu et al. (2017) | 2.31 yr ± 2.12 standard deviation/57 females and 51 males | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Diarrhea, fever, and vomiting | Generalized tonic–clonic seizures | Not reported | Hyperleukocytosis and raised C-reactive protein levels | Not reported |

Febrile Afebrile seizure |

Not reported | Full recovery except for one death due to hypovolemic shock |

| Chan et al. (2011) | 15–23 mths/95 males, 78 females | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Diarrhea, vomiting, and blood-stained stool | Generalized tonic–clonic seizures | Sodium was slightly elevated | Hyperleukocytosis, hyperglycemia, and raised C-reactive protein levels | Neuroimaging data were normal. Electroencephalography revealed occasional sharp waves | Afebrile seizures | Not reported | Full recovery |

| Shima et al. (2019) | 2.8 yr/ten males and 19 females | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and shock in 12 | Delirious behavior, status epilepticus, seizures | Cell blood count was within normal range except for two children |

Platelet count decreased in five children; increased aspartate aminotransferase levels in thirteen cases; increased alanine aminotransferase levels in ten cases Increased lactate dehydrogenase in eighteen cases Increased creatinine kinases in seven cases Increased blood-urea-nitrogen in nine cases Serum creatinine is elevated in three cases Glutamate is decreased in five cases Hypernatremia in nine cases Decreases bicarbonate in twenty-one cases |

Clinical and neuroimaging could classify the patients as acute encephalopathy and late reduced diffusion in eight; hemorrhagic shock and encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion in seven; mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesions in three; acute necrotizing encephalitis in one; acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in one; and one with cerebellitis. No neuroimaging data in the two remaining | Norovirus-induced encephalitis/encephalopathy | Steroid pulse therapy in twenty-two patients, intravenous immunoglobulin in eleven patients, plasma exchange, cyclosporin, dextromethorphan, and edaravone | Good outcome in 13 and poor outcome in 15 cases |

| Kim et al. (2021) | 1–5 yr/153 males and 184 females | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Fever, vomiting, and diarrhea | Benign convulsion | Normal | Normal | Normal | Benign convulsion | Not reported | Full recovery |

| Jiang et al. (2022) | 11–36 mths/27 males and 22 females | A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of a stool sample | Fever, vomiting, and diarrhea | Generalized tonic–clonic seizure | Normal | Slightly elevated C-reactive protein | Normal electroencephalography in all but one | Benign convulsion and febrile seizure | Not reported | Full recovery |

| Kim et al. (2018) | 44 patients/18 ± 5.57 months | Stool viral tests and multiplex polymerase chain reaction | Enteric or general symptoms with diarrhea and vomiting | Generalized tonic–clonic seizures, generalized tonic, non-motor, and focal tonic | Not reported | Normal | Mostly seizures with different times of onset or occurrence. Electroencephalography abnormalities included interictal (26), posterior slowing (15), and small sharp or spikes (2) | Benign convulsions | Not reported | Full recovery on subsequent check-ups |

Afebrile infantile seizures with signs of acute gastroenteritis and no other illnesses that cause seizures (e.g., hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalance, and cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities) are referred to as benign seizures with mild gastroenteritis (Kawano et al. 2007). Norovirus is probably the most common viral pathogen causing benign seizures with mild gastroenteritis (Kim et al. 2018). In a landmark clinical series that included 64 patients infected by norovirus and 101 by rotavirus, norovirus infection was associated with a higher seizure rate in young children than rotavirus infection (19, 29.7% vs. 5, 5%; p < 0.001) (Chen et al. 2009). Only six patients received short-course anticonvulsant therapy, and none of the 19 patients had any neurological sequelae. Compared with rotavirus-associated benign seizures with mild gastroenteritis, those caused by norovirus are less frequent during spring, more frequently seen with vomiting, have a shorter interval from enteric symptom onset to seizure onset, and more frequently show a posterior slowing in electroencephalography (Kim et al. 2018). What seems clear is that young age may be a risk factor for norovirus-associated benign seizures (Kawano et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2009), and long-term neurological sequelae are uncommon.

Kimura et al. first reported a case of norovirus-associated encephalopathy in a 60-year-old female (2010). Similarly, other pediatric patients with norovirus-associated encephalopathy have been reported (Obinata et al. 2010, Tantillo et al. 2021). The common thread among the abovementioned pediatric patients included high-voltage slow waves on electroencephalography without paroxysmal discharges (Obinata et al. 2010); two patients also presented with increased muscle tone and slow pupillary light reflex. Sánchez-Fauquier et al. (2015) reported a patient with encephalitis who presented disorganized cerebral activity in electroencephalography. On the other hand, Yoo et al. (2023) described an infant with norovirus-associated meningoencephalitis who presented with status epilepticus during admission, revealing suppressed pattern activities with continuous right central spike discharge at 3–5-s intervals on electroencephalography and concomitant disseminated intravascular coagulation. A patient with suggestive cerebellitis with mild language delay, gait disturbances, and asymmetric high T2-weighted signal intensity with leptomeningeal enhancement in the right cerebellar folia has also been reported (Chung et al. 2017), as well as another patient with bulbar involvement who presented with diplopia, transient ataxia, bilateral periorbital pain, and stage 4 bilateral papilledema (Yoo et al. 2023).

Miller Fisher syndrome is a rare spectrum of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a broad syndrome encompassing several types of acute immune-mediated polyneuropathies. Both entities are thought to result from an aberrant acute autoimmune response to a previous infection (e.g., Haemophilus influenza, Campylobacter jejuni, cytomegalovirus, or SARS-CoV-2, among others) (Koga et al. 2019, Gutiérrez-Ortiz et al. 2020), suggesting a para-viral or postviral process. Intriguingly, autoimmune demyelinating and neuroinflammatory disorders have also been reported in the context of norovirus infection. Eltayeb and Crowley (2012) first reported an adult case of norovirus-related Guillain-Barré syndrome who presented with general symptoms of norovirus infection, progressive ascending weakness, hyporeflexia, numbness, mild facial weakness, deteriorating respiratory failure, and autonomic dysfunction. Shimizu and Tokuda (2012) reported a case of Miller Fisher syndrome in an adult female who had presented with enteric features of norovirus followed by blurred vision, ataxic gait, pins, and needle-like sensations in the hands bilaterally, progressive ascending weakness, and upward and downward gaze alterations. The two patients showed no significant changes in the brain and spinal MRI; however, neurophysiological studies were consistent with acquired demyelinating polyneuropathy in the patient with Guillain–Barre syndrome. Disorder related to direct myelin injury in the form of transient myelin-sheath edema has also been reported in another case of norovirus infection (Saran et al. 2019). These two cases suggest that norovirus infection should be ruled out in those patients with post-diarrheal immune-driven disorders, especially in endemic territories.

Gutierrez-Camus et al. (2022) reported white matter injury in a 2-day-old patient following a norovirus infection. The patient presented abnormal facial and limb movements and generalized tonic–clonic seizure episodes. On the other hand, Nakakubo et al. (2016) reported a patient with norovirus-induced cerebellar infarction associated with an underlying antiphospholipid syndrome in a 6-year-old male. These cases open avenues to understanding the diverse nature of the post-infectious nature of neurological sequelae.

Noteworthy to mention that, apart from the patients with afebrile seizures, who had a good outcome, most who required intravenous immunoglobulin, immunosuppressives, and supportive management showed full recovery (Table 1).

Discussion

This study is the first-ever attempt to explore neurological manifestations in norovirus infection through a systematic review of peer-reviewed data. The current review is important in advancing our knowledge and understanding of norovirus’s neurological complications, primarily considered a gastrointestinal virus in adult and pediatric populations. Several neurological manifestations of norovirus infection affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems have been reported (Table 1). Despite this, these complications might be under‐recognized. Thus, we have only found seven hundred and seventy-four patients with de novo norovirus-associated neurological disorders in the present review, mainly benign seizure disorders, particularly in young infants.

The pathogenesis of norovirus-associated neurological manifestations may be mediated by either neurotropism or aberrant immune-mediated injury, or both, depending on the affected system. Evidence supports an aberrant immune-mediated injury. First, there is a gap between the enteric symptom onset and the first neurological symptoms (in the cases of seizures may be a couple of days (Kim et al. 2018), and in the cases of acute immune-mediated polyneuropathies 10 to 14 days) (Shimizu and Tokuda 2012; Eltayeb and Crowley 2012), suggesting a post-infectious autoimmune process. Second, the spectrum of Guillain–Barré syndrome, including Miller Fisher syndrome, is a prototype for post-infectious immune-mediated neuropathy with known infectious triggers (Koga et al. 2019). Third, in the case of post-norovirus Miller Fisher syndrome, antibodies against ganglioside (i.e., GQ-1b) were detected (Eltayeb and Crowley 2012). There is evidence that sialic acid-containing glycosphingolipids (gangliosides) are also ligands for human norovirus (Han et al. 2014). Hence, cross-reactivity and molecular mimicry between norovirus antigenic epitopes and gangliosides, essential in modulating nervous system integrity, notably at the node of Ranvier, may bring immune-driven neuropathy in norovirus-induced Guillain–Barré syndrome and its variants. Fourth, a patient with norovirus-associated encephalopathy showed elevated concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6, interleukin-10, interferon-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α suggesting that her encephalopathy was related to hypercytokinemia (Obinata et al. 2010). Finally, last but not least, a dramatic response to intravenous immunoglobulin in many cases of norovirus-associated neurological manifestations points towards an underlying immune-driven process (Table 1). Immunotherapy with intravenous immunoglobulin could be used to treat norovirus-associated neurological manifestations. Its efficacy would be much improved if the immune IgG antibodies were collected from patients who have recovered from norovirus infection in the surrounding area to increase the chance of neutralizing the virus.

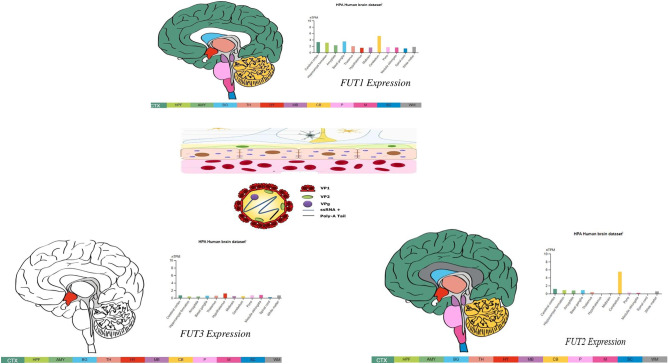

On the other hand, direct neurotropism as a pathogenic process did not lie far behind. Specifically, viral RNA of norovirus in the cerebrospinal fluid has been detected in two cases of encephalitis (Gutierrez-Camus et al. 2022, Ito et al. 2006). Studies on immunodeficient mice infected by various murine norovirus have revealed changes in brain histology, suggesting that immunodeficiency may favor neuro-invasion of the norovirus (Haga et al. 2016). Two hypotheses could explain how norovirus could potentially reach the central nervous system. First, genome-wide CRISPR screening and cell line-based in vitro studies suggest that murine norovirus uses members from the CD3000 family (a group of proteins playing vital roles in immune responses), such as CD300ld or CD300lf, as a receptor (Haga et al. 2016). Besides, other members from this family, such as CD300e and CD300f, are homologous to murine CD300ld and CD300lf from the human [Blast] brain (Homological sequence has been found using NCBI blastp; RID-TDPK0RX013) (Fig. 2). Human norovirus could invade the central nervous system through these proteins. Second, there is some evidence that different polymorphisms on different histo-blood group antigens, such as FUT1, FUT2, and FUT3, are linked to high susceptibility toward norovirus infection (Nordgren and Svensson 2019; Ward et al. 2006) (Fig. 2). Human norovirus could cross the blood–brain barrier and bind through these antigens, which are expressed in various regions of the human brain (Fig. 2). Hence, neuro-invasion could alternatively occur through brain endothelial cell-specific blood group antigens.

Fig. 2.

Expression in the brain of histo-blood group antigens FUT1, FUT2, and FUT3 (ref: Human Protein Atlas)

There are some limitations in the current review. Given the notable asymmetry between the total number of affected cases and reported norovirus-associated neurological disorders, it can be assumed that neurological cases are under‐reported. The current review is, however, based on several hundreds of cases, even after an extensive search of available literature. In addition, several available reports do not describe the timeline of events in an organized manner, making interpretation difficult. Laboratory, electroencephalography, and neuroimaging features have also not been detailed in a few cases. In addition, considerable heterogeneity in the available data may be considered a hindrance in advanced analysis. Finally, we have not included non‐English articles. Despite these shortcomings, the present organized review will be an introductory guide for clinicians dealing with neurological disorders that appear in norovirus infection.

Only a few studies have addressed the pathogenesis of norovirus-related neurological complications. Hence, further work must be done to understand the mechanisms responsible for these complications. With the growing frequency of such cases, our study could help clinicians recognize these neurological manifestations better and earlier while deepening the understanding of this viral infection.

Acknowledgements

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011-287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD—platform for the tracking of movement disorder), and the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451).

Author contribution

Shramana Deb collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; (2) the statistical analysis design; and (3) the writing of the manuscript’s first draft and the review and critique. Ritwick Mondal collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; and (2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Durjoy Lahiri collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; and (2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Gourav Shome collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; and (2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Akash Guha Roy collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; and (2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Vramanti Sarkar collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; and (2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Julián Benito-León collaborated with (1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; and (2) the review and critique of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shramana Deb, Email: shramanadeb1995@gmail.com.

Ritwick Mondal, Email: ritwickraw@gmail.com.

Durjoy Lahiri, Email: dlarihi1988@gmail.com.

Gourav Shome, Email: gshome007@gmail.com.

Aakash Guha Roy, Email: guharoyaakash@gmail.com.

Vramanti Sarkar, Email: vramantisarkar@gmail.com.

Shramana Sarkar, Email: shramana99.sarkar@gmail.com.

Julián Benito-León, Email: jbenitol67@gmail.com.

References

- Adler JL, Zickl R. Winter vomiting disease. J Infect Dis. 1969;119(6):668–673. doi: 10.1093/infdis/119.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Obaidi MMJ, Bahadoran A, Wang SM, Manikam R, Raju CS, Sekaran SD. Disruption of the blood brain barrier is vital property of neurotropic viral infection of the central nervous system. Acta Virol. 2018;62(1):16–27. doi: 10.4149/av_2018_102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini L, Mardari R, Toldo I, Calderone M, Battistella PA, Laverda AM, Sartori S. Norovirus gastroenteritis and seizures: an atypical case with neuroradiological abnormalities. Neuropediatrics. 2011;42(4):167–169. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CM, Chan CW, Ma CK, Chan HB. Norovirus as cause of benign convulsion associated with gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47(6):373–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Tsai CN, Lai MW, et al. Norovirus infection as a cause of diarrhea-associated benign infantile seizures. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(7):849–855. doi: 10.1086/597256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung LYJ, Lee KC, Kim GH, Eun SH, Eun BL, Byeon JH. Norovirus associated cerebellitis in a previous healthy 2-year-old girl. Ann Child Neurol. 2017;25(3):179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Eltayeb KG, Crowley P (2012) Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with Norovirus infection. BMJ Case Rep 2012. 10.1136/bcr.02.2012.5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frenck R, Bernstein DI, Xia M, et al. Predicting susceptibility to norovirus GII.4 by use of a challenge model involving humans. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(9):1386–1393. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Camus A, Valverde E, Del Rosal T, et al. Norovirus-associated white matter injury in a term newborn with seizures. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41(11):917–918. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Ortiz C, Méndez-Guerrero A, Rodrigo-Rey S, San Pedro-Murillo E, Bermejo-Guerrero L, Gordo-Mañas R, de Aragón-Gómez F, Benito-León J. Miller Fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19. Neurology. 2020;95(5):e601–e605. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K, Fujimoto A, Takai-Todaka R, et al. Functional receptor molecules CD300lf and CD300ld within the CD300 family enable murine noroviruses to infect cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(41):E6248–E6255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605575113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Tan M, Xia M, Kitova EN, Jiang X, Klassen JS. Gangliosides are ligands for human noroviruses. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(36):12631–12637. doi: 10.1021/ja505272n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington PR, Lindesmith L, Yount B, Moe CL, Baric RS. Binding of Norwalk virus-like particles to ABH histo-blood group antigens is blocked by antisera from infected human volunteers or experimentally vaccinated mice. J Virol. 2002;76(23):12335–12343. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.23.12335-12343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington PR, Vinjé J, Moe CL, Baric RS. Norovirus capture with histo-blood group antigens reveals novel virus-ligand interactions. J Virol. 2004;78(6):3035–3045. doi: 10.1128/jvi.78.6.3035-3045.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert TP, Brierley I, Brown TD. Identification of a protein linked to the genomic and subgenomic mRNAs of feline calicivirus and its role in translation. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 5):1033–1040. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-5-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MH, Lin KL, Wu CT, Chen SY, Huang GS. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for seizures associated with norovirus gastroenteritis in childhood. J Child Neurol. 2017;32(9):810–814. doi: 10.1177/0883073817707302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson AM, Atmar RL, Marcus DM, Estes MK. Norwalk virus-like particle hemagglutination by binding to h histo-blood group antigens. J Virol. 2003;77(1):405–415. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.1.405-415.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JL, Mackenzie JM. Subcellular localization of the MNV-1 ORF1 proteins and their potential roles in the formation of the MNV-1 replication complex. Virology. 2010;406(1):138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Takeshita S, Nezu A, et al. Norovirus-associated encephalopathy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(7):651–652. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000225789.92512.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes MK. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology. 1993;195(1):51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Shi K, Li S et al (2022) Characteristics of blood tests in norovirus-associated benign convulsions with mild gastroenteritis in children. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1769215/v1

- Kapikian AZ, Wyatt RG, Dolin R, Thornhill TS, Kalica AR, Chanock RM. Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. J Virol. 1972;10(5):1075–1081. doi: 10.1128/JVI.10.5.1075-1081.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano G, Oshige K, Syutou S, et al. Benign infantile convulsions associated with mild gastroenteritis: a retrospective study of 39 cases including virological tests and efficacy of anticonvulsants. Brain Dev. 2007;29(10):617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BR, Choi GE, Kim YO, Kim MJ, Song ES, Woo YJ. Incidence and characteristics of norovirus-associated benign convulsions with mild gastroenteritis, in comparison with rotavirus ones. Brain Dev. 2018;40(8):699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Ha DJ, Lee YS, Chun MJ, Kwon YS. Benign convulsions with mild rotavirus and norovirus gastroenteritis: nationwide data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service in South Korea. Children (basel) 2021;8(4):263. doi: 10.3390/children8040263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Goto H, Migita A et al (2010) An adult norovirus-related encephalitis/encephalopathy with mild clinical manifestation. BMJ Case Rep 2010:bcr0320102784. 10.1136/bcr.03.2010.2784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Koga M, Kishi M, Fukusako T, Ikuta N, Kato M, Kanda T. Antecedent infections in Fisher syndrome: sources of variation in clinical characteristics. J Neurol. 2019;266(7):1655–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09308-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD et al (2008) Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med 5(2):e31. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marionneau S, Ruvoën N, Le Moullac-Vaidye B, et al. Norwalk virus binds to histo-blood group antigens present on gastroduodenal epithelial cells of secret or individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(7):1967–1977. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medici MC, Abelli LA, Dodi I, Dettori G, Chezzi C. Norovirus RNA in the blood of a child with gastroenteritis and convulsions–a case report. J Clin Virol. 2010;48(2):147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Kurihara C, Oka T et al (2013) Norovirus binding to intestinal epithelial cells is independent of histo-blood group antigens. PLoS One 8(6):e66534. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nakakubo S, Sasaki D, Uetake K, Kobayashi I (2016) Stroke during norovirus infection as the initial episode of antiphospholipid syndrome. Glob Pediatr Health 3:2333794X15622771. 10.1177/2333794X15622771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Noel JS, Fankhauser RL, Ando T, Monroe SS, Glass RI. Identification of a distinct common strain of "Norwalk-like viruses" having a global distribution. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(6):1334–1344. doi: 10.1086/314783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgren J, Svensson L (2019) Genetic susceptibility to human norovirus infection: an update. Viruses 11(3):226. 10.3390/v11030226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Obinata K, Okumura A, Nakazawa T, et al. Norovirus encephalopathy in a previously healthy child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(11):1057–1059. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e78889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MM, Widdowson MA, Glass RI, Akazawa K, Vinjé J, Parashar UD. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(8):1224–1231. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robilotti E, Deresinski S, Pinsky BA. Norovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(1):134–164. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00075-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Fauquier A, González-Galán V, Arroyo S, Rodà D, Pons M, García JJ. Norovirus-associated encephalitis in a previously healthy 2-year-old girl. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(2):222–223. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saran S, Neyaz Z, Azim A. Norovirus-induced gastroenteritis presenting with reversible quadriparesis in an adult suggesting transient intramyelinic edema: a rare case report. Indian Journal of Case Reports. 2019;5(1):16–18. doi: 10.32677/IJCR.2019.v05.i01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shima T, Okumura A, Kurahashi H, Numoto S, Abe S, Ikeno M, Shimizu T. Norovirus-associated Encephalitis/Encephalopathy Collaborative Study investigators. A nationwide survey of norovirus-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy in Japan. Brain Dev. 2019;41(3):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Tokuda Y (2012) Miller Fisher syndrome linked to Norovirus infection. BMJ Case Rep 2012:bcr2012007776. 10.1136/bcr-2012-007776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Chang KO, et al. Cleavage map and proteolytic processing of the murine norovirus nonstructural polyprotein in infected cells. J Virol. 2006;80(16):7816–7831. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00532-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantillo G, Kagita N, LaVega-Talbott M, Singh A, Kaufman D. Norovirus causes pediatric encephalopathy and status epilepticus: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Epilepsy. 2021;10(03):135–139. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1725990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne LG, Goodfellow IG. Norovirus gene expression and replication. J Gen Virol. 2014;95(Pt 2):278–291. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.059634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Wobus CE, Thackray LB, et al. Pathology of immunodeficient mice with naturally occurring murine norovirus infection. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34(6):708–715. doi: 10.1080/01926230600918876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson MA, Monroe SS, Glass RI. Are noroviruses emerging? Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(5):735–737. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.041090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MJ, Ha DJ, DH Kim, Kwon YS. Two cases of norovirus gastroenteritis associated with severe neurologic complications. Ann Neurol. 2023;31(1):56–58. doi: 10.26815/acn.2022.00262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]