Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate changes in clinicians’ use of evidence-based practice, openness toward evidence-based practice, and their acceptance of organizational changes after a rehabilitation hospital transitioned to a new facility designed to accelerate clinician-researcher collaborations.

Design:

Three repeated surveys of clinicians before, 7–9 months and 2.5 years after transition to the new facility.

Setting:

Inpatient rehabilitation hospital.

Participants:

Physicians, nurses, therapists, and other healthcare professionals (410, 442, and 448 respondents at time 1, 2, and 3 respectively).

Interventions:

Implementation of physical (architecture, design) and team-focused (champions, leaders, incentives) changes in a new model of care to promote clinician-researcher collaborations.

Main outcome measures:

Adapted versions of the Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire (EBPQ), the Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale (EBPAS), and the Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale (OCRBS) were used. Open-ended survey questions were analyzed through exploratory content analysis.

Results:

Response rates at Times 1, 2, and 3 were 67% (n=410), 69% (n=422), and 71% (n=448), respectively. After accounting for familiarity with the model of care, there was greater reported use of evidence-based practice at Time 3 compared to Time 2 (adjusted meant2=3.51, standard error (SE)=0.05; adj. meant3=3.64, SE=0.05; p=0.043). Attitudes toward evidence-based practices were similar over time. Acceptance of the new model of care was lower at Time 2 compared to Time 1, but rebounded at Time 3 (adjusted meant1=3.44, SE=0.04; adj. meant2=3.19, SE=0.04; p<.0001; adj. meant3=3.51, SE=0.04; p<.0001). Analysis of open-ended responses suggested that clinicians’ optimism for the model of care was greater over time, but continued quality improvement should focus on cultivating communication between clinicians and researchers.

Conclusions:

Accelerating clinician-researcher collaborations in a rehabilitation setting requires sustained effort for successful implementation beyond novel physical changes. Organizations must be responsive to clinicians’ changing concerns to adapt and sustain a collaborative translational medicine model and allow sufficient time, probably years, for such transitions to occur.

Keywords: inpatient rehabilitation facility, interdisciplinary rehabilitation, health systems, implementation, translational research, translational medicine, evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice (EBP), defined by Sackett and colleagues is “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient.”1 EBP is a core concept within rehabilitation that integrates research, clinician expertise, and patient perspectives.1–5 However, the rehabilitation field realizes that passive diffusion of research into practice is slow and ineffective.5 Organizations that embrace a research culture encourage clinicians’ collaboration in research. This cultural change expands the role of the clinician, improves the clinical relevance of research, and increases clinician-researcher collaboration opportunities.2,6

Creating an organizational culture that accelerates application of research into practice, and drives innovative rehabilitation research, requires intentional implementation strategies.2,5 Two implementation pathways that could impact organizational culture include (1) physical strategies that change architecture and design to foster proximity and clinical-research collaborations7–9 and (2) team-focused strategies including champions, leadership, and staff incentive structures to change culture related to evidence-based practice.10–12

Changing the physical structure of a facility to promote integration of research into the clinical enterprise includes architecture and design elements. In business literature, promoting proximity and open workspaces has been suggested to improve networking, collaboration, and innovation.7–9 In healthcare literature, research reports have explored the physical movement of a hospital focusing on the planning process required for the immediate move to a new building.13,14 However, they do not report on intentional or unintentional cultural shifts that may accompany their architectural or design changes.

Team-focused implementation strategies designed to change organizational culture can target the people within the organization, including leadership, clinical providers, and staff.2,15,16 Such changes may transform clinicians’ and researchers’ roles to meet the goals of a research-driven organization.9,10,12 Strategies used to achieve cultural changes may include engaging leadership and champions,10,11 training clinical providers in new roles and providing feedback, and incentivizing clinician-researcher collaborations through professional development opportunities and funding.2,15–17 Empowering more clinicians to engage in the research enterprise may help them value and understand evidence-based practice to a greater extent.2 Evaluating the consequences of various implementation strategies on these cultural changes requires the use of pragmatic assessment tools18 repeated over time to monitor and adapt implementation strategies and thus sustain the cultural shift.19,20

The purpose of this study was to evaluate how physical strategies (e.g. architecture and design) and team-focused strategies (e.g., champions, culture, incentives) were associated with the adoption and acceptance of an organizational change. The overall goal of the organizational change was to develop a research-focused clinical culture in a translational research hospital, which we call the AbilityLab Model of Care. This model is further defined as rehabilitation that integrates researchers in the clinical environment with a goal to accelerate innovation in evidence-based practice. Using validated instruments, we assessed aspects of this culture through clinicians’ perceived use of EBP, attitudes toward EBP, and their acceptance of the AbilityLab Model of Care immediately before, 7–9 months after, and 2.5 years after moving into a new translational research hospital. Secondarily, we describe clinicians’ responses to open-ended questions dealing with various aspects of the change that were going well as well as suggestions for improvement.

METHODS

This mixed methods, prospective, longitudinal, observational study uses validated surveys and open-ended questions to examine clinicians’ perceived use of EBP, attitudes toward EBP, and their acceptance of an organizational change at three times.

Context and Timeline:

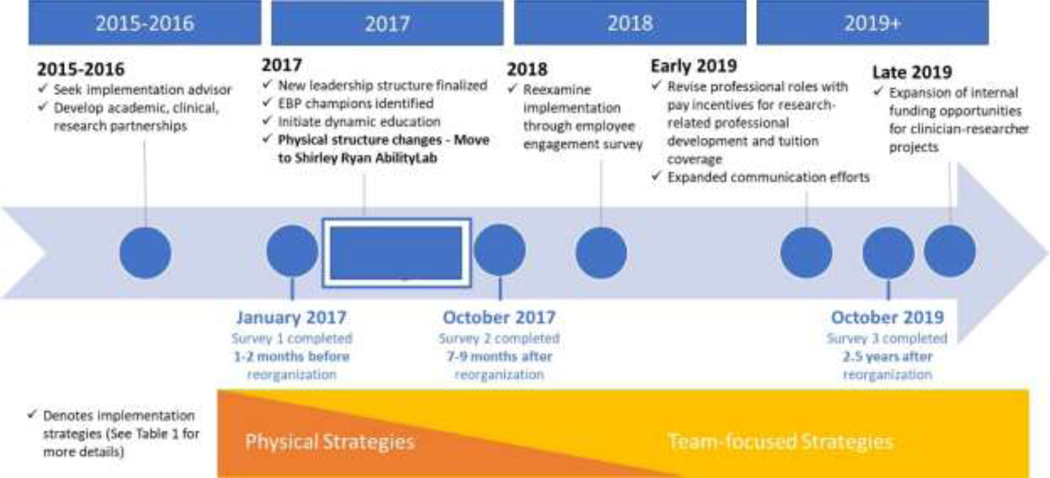

In 2015, hospital leadership organized an academic-clinical-research work group to quantify EBP attitudes during and after the transition from the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, a free-standing rehabilitation hospital, to a new state-of-the-art facility, the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (SRAlab). The Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (SRAlab) is a 242 bed academic rehabilitation hospital in an urban area. The transition was completed with the goal to fulfill an organizational priority to accelerate translational medicine and rehabilitation research. Figure 1 highlights key aspects of the survey and implementation timeline. One key component of the transition was the physical move to a new hospital building in March 2017, which was designed to co-locate researchers in therapy spaces and provide new rehabilitation technology for patient care. Other key components of the transition included team-focused changes that developed over the course of the project (2015-present). A new leadership structure and champions in the delivery of EBP protocols were in place by the physical move. At the time of the move, leadership structure was de-centralized, providing unit leaders and champions to interact with clinician and researchers in each unit. Then in early 2019, the organization expanded professional development activities to promote clinician engagement in research, including pay incentives, promotion, tuition reimbursement, and internal funding opportunities for clinician-driven research and scientific discovery across the translational research spectrum.

Figure 1.

Timeline presenting key dates for the survey (lower row, blue) and implementation strategies (upper row, black).

The academic-clinical-research partners met approximately monthly from 2016 through 2018, with more frequent meetings during critical windows to discuss potential implementation determinants (a priori and ongoing barriers discussions) and strategies using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research21 and the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change compilation.12 These implementation components were discussed using the Implementation Research Logic Model.22 The physical and team-based implementation strategies are described in Table 1 in accordance with Proctor and colleagues (2013).23

Table 1:

Implementation Strategy Specification22

| Action | Develop academic/clinical/research workgroup with implementation experts | Physical move of the organization and colocation of clinicians and researchers | Decentralize leadership structure | Use of “champions” for delivery of evidence-based practices | Developm ent of pay incentives, promotion, tuition reimbursement program, and internal funding opportunities | Opportunities for shadowing clinical and research peers, lunch and learn events, and social and educational gatherings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation strategy name12 | Use an implementation advisor Develop academic partnerships |

Change physical structure and equipment Ongoing consultation and educational meetings |

Revise professional roles | Identify and prepare champions Revise professional roles |

Alter allowance / incentive structures | Promote network weaving |

| Actor(s) | Senior organizational leaders, academic partners | Senior organizational leaders | Senior and middle organizational leader | Middle and front-line organizational leaders | Senior organizational leaders | Middle and front-line organizational leaders |

| Target(s) of the action | Organizational leadership (senior leadership) | All staff | Clinicians and researchers | Clinicians | Clinicians and researchers | Clinicians and researchers |

| Dose | Varied based on needs (met weekly earlier in project, decreasing to quarterly) | One instance of major change (with iterative improvements as needed based on consultations, dynamic education, and feedback) | Leadership roles added at senior, middle, and front-line levels to facilitate clinical-research integration with more regular presence | Number of champions (lab therapists) per topic area varies based on need (e.g. gait, shoulder, cardiopulmonary, pain, wheelchair skills, etc) | Four ‘doses’ or types of funding target different populations and purposes (pay incentives, promotion, tuition reimbursement, internal research funding) | Local-level dosing (e.g., unit or team-based lunch n’ learns) and organization-level dosing (e.g., weekly education al grand rounds) |

| Justification | Collaborative research between organization senior researchers and academic experts12 | Research that suggests proximity and open workspaces might improve collaboration and innovation.7–9 | Knowledge brokers (social network and brokerage theory)11 | Knowledge brokers (social network and brokerage theory)10–11 | Research that suggests providing financial and other types of compensation for research engagement 2 | Brokering knowledge and building research competencies 2,11 |

| Implementat-ion outcomes |

Acceptability was measured by the EBPAS and the OCRBS Penetration and Effectiveness were indirectly measured by the EBPQ Feasibility was measured through the open-ended questions described in the report |

|||||

Note: Temporality is noted in the timeline figure

Abbreviations: EBPAS, Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale; EBPQ, Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire; OCRBS, Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale

Data Collection

The online survey was administered via REDCap to clinicians at three time points: (Time 1) 1–2 months before the move (Jan-Mar 2017), (Time 2) 7–9 months after the move (Nov-Dec 2017), when organizational supports were only partially implemented, and (Time 3) two years later (Nov-Dec 2019), when the physical and team-focused supports were mostly implemented. (Figure 1) To promote response rates, all respondents received a token incentive, such as a branded mug or lunch bag.

Population Studied

Clinicians, researchers, leaders, and selected support staff completed the survey. The current study includes the responses of inpatient clinicians—rehabilitation physicians, nurses, therapists (physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists), and other clinicians (e.g. dieticians, psychologists, care managers, respiratory therapists). We excluded clinicians who self-identified as having primary or secondary research or leadership roles. The survey was sent to three cross-sectional samples, which included 612 clinicians at time 1, 612 clinicians at time 2, and 631 clinicians at time 3. Approval for this study was obtained by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University.

Measures

The academic-clinical-research work group designed a survey to provide feedback on how the physical and team-focused strategies influenced clinician and researcher interactions. We adapted questions from validated measures24–26 and selected a subset of questions that applied to our context. The measures were adapted to shorten the survey, reduce redundant questions, and focus on salient concerns identified by the academic-clinical-research work group.27 A confirmatory factor analysis validated the modified, pragmatic, measures as reliable and invariant across respondent types prior to administering the survey.27

Clinicians completed three measures of distinct constructs: (1) perceived use of evidence-based practices (EBPQ),24 (2) attitudes toward using evidence-based practices (EBPAS),25 and (3) acceptance of the organizational change to the new translational research-focused AbilityLab model of care (OCRBS).26 All measures used a 5-point Likert-type rating scale for consistency, where high scores indicated more EBP use, EBPAS openness, and more acceptance of the model. Supplemental Material 1 presents the questions asked and each measures’ internal consistencies.

Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire (EBPQ)24 measures EBP use, attitudes, and knowledge.24 The 24-items are assigned to three subscores: (1) Practice of EBP, (2) Attitudes toward EBP, and (3) Knowledge/Skills associated with EBP. We selected 5 items from the Practice of EBP subscore. The modified EBPQ practice questions were scored on a five-point Likert scale, with high scores indicating more EBP use. Moderate to strong internal consistencies were attained with the original questionnaire (α=0.85),24 as well as our adapted version (range time 1–3, α=0.89–0.94).

Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale (EBPAS)25 measures attitudes toward adopting and delivering EBPs.25 It consists of 15 original items in four subscores: (1) Openness to new practices, (2) Intuitive appeal of EBP, (3) Likelihood of adopting EBP given requirements to do so, and (4) Perceived divergence of usual practices from evidence-based interventions. We asked 7 items (3 items from Openness, 2 from Appeal, 1 from Requirements, and 1 from Divergence), scoring only the subscale measuring openness to using EBP. Moderate to strong internal consistencies were attained from the original questionnaire (α=0.77),25 and our adapted version of the 3-question openness subscale (range time 1–3, α=0.90–0.92).

Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale (OCRBS)26 measures beliefs and attitudes towards a current or proposed organizational change.26 In this case, the organizational change included both the physical and team-focused changes related to the AbilityLab Model of Care. It consists of 24 items measuring the degree of buy-in and the impact of five constructs that could adversely affect the success of change: (1) Discrepancy, (2) Appropriateness, (3) Efficacy, (4) Principal Support, and (5) Valence. We selected 8 items (1 item from Discrepancy, 1 from Appropriateness, 3 from Efficacy, 1 from Principal Support, and 2 from Valence). Moderate to strong internal consistencies were attained from the original questionnaire (α=0.91),26 and our adapted version (range time 1–3, α=0.88–0.91). The adapted measure, which included items from each domain is a measure of overall acceptance of the organizational change.

Additional questions:

The survey also included questions related to experience at the organization, interdisciplinary communication barriers and frequency, and demographic characteristics. In this report, we group respondents based on their role as physician, allied health therapist, nurse, or other. Years at the organization was measured as a continuous response and familiarity with the model of care was measured with a four-point Likert item “How familiar are you with the model of care as defined above?” The definition of “model of care” was “rehabilitation that integrates researchers in the clinical environment. The goal is to accelerate innovation in evidence-based practice.” We also asked open-ended questions to elicit information about things that were going well and opportunities for improvement at each time point. At time 3, these questions were: (1) What aspects of the AbilityLab Model of Care are working well; (2) What suggestions do you have to improve the AbilityLab Model of Care; (3) What training would you need or want to improve your delivery of the AbilityLab Model of Care; and (4) If you have other feedback on the AbilityLab Model of Care, please share here. The results of these open ended questions were used to inform implementation of the AbilityLab Model of Care, particularly the identification of team-focused strategies, such as engaging leadership and champions, training and mentorship for professional development, and incentivizing clinician-researcher collaborations.

Statistical Analyses

Data anonymity prevented our linking individual responses over time; thus, we treat these data as three cross-sectional pooled data surveys rather than a typical longitudinal dataset. To accommodate the unbalanced data, we used general linear models to conduct an independent-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) estimating mean outcomes over time in the three instruments of interest (EBPQ, EBPAS, OCRBS). Covariates of interest included: (1) clinical role; (2) familiarity with the model of care; and (3) years at the organization. For the final models, we chose covariates based on whether they were associated with the outcome of interest. Univariate results indicated independent associations between each instrument and (1) clinical role and (2) familiarity with the model of care. Because years at the organization was not associated with the outcome variable, we eliminated it as a control variable from final models. Three models assessed changes over time in EBPQ, EBPAS, and OCRBS, with each model controlling for clinical role and familiarity with the model of care. When the ANOVA results indicated a significant effect of either time or clinical role, we examined Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons. Significance level (α) was set to p<0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS.28

Open-ended question analysis used a combination of conventional and summative content methods.29 Three coders (LS, LO, and MR) developed a coding structure while coding a random 25% sample of responses to question 1. Then, two coders categorized responses to all surveys, with the third coder assisting to find consensus on disagreements. When more than one code applied to a response, coders selected a primary “best-fitting” option. Then, they tabulated primary codes for each response.

RESULTS

Quantitative results

Demographic results and response rates are reported in Table 2. Response rates for the clinicians were highly consistent at 67% (n=410) for survey 1, 69% (n=422) for survey 2, and 71% (n=448) for survey 3. For EBPQ, there was a significant effect of both time (F2 DF=8.90, p=0.0001) and clinical role (F2 DF=71.23, p<.0001), where allied health and physicians scored higher than nurses. For EBPAS, there was a significant effect of clinical role (F2 DF=14.92, p<.0001), where allied health and nurses scored higher than physicians. Similarly for OCRBS, there was a significant effect of time (F2 DF=24.58, p<.0001) and clinical role (F2 DF=27.68, p<.0001), where nurses scored the highest, followed by allied health, followed by physicians. There were no significant interactions between time and clinical role for any of the instruments indicating that each role was consistent over time (Table 3). ANOVA results are reported in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 2. Post hoc Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons for the significant ANOVA main effects are reported below and in Figure 2.

Table 2:

Demographics of Surveys 1, 2, and 3

| Demographics at Time 1 (n=410) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Physicians (n=73 (17.8%)) | Nurses (n=141 (34.4%)) | Allied health (n=196 (47.8%)) | X2 | p | |

|

| |||||

| Age (n (%)) | X2=61.24 (DF=10) | <.0001 | |||

| 18–24 | 0 (0%) | 20 (15.4%) | 3 (1.7%) | ||

| 25–34 | 28 (42.4%) | 62 (47.7%) | 117 (64.6%) | ||

| 35–44 | 15 (22.7%) | 22 (16.9%) | 41 (22.7%) | ||

| 45–54 | 11 (16.7%) | 16 (12.3%) | 12 (6.6%) | ||

| 55–64 | 9 (13.6%) | 10 (7.7%) | 8 (4.4%) | ||

| 65+ | 3 ( 4.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender (female) | 30 (44.1%) | 116 (89.9%) | 169 (91.9%) | X2=86.13 (DF=2) | <.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Familiarity with MoC | X2=19.43 (DF=4) | 0.0006 | |||

| Not at all/to a slight extent | 12 (16.4%) | 50 (35.5%) | 50 (25.5%) | ||

| To a moderate extent | 29 (39.7%) | 66 (46.8%) | 86 (43.9%) | ||

| To a great/very great extent | 32 (43.8%) | 25 (17.7%) | 60 (30.6%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Years at org. (median (IQR)) | 5 (3, 11) | 5 (3, 11) | 3 (1, 8) | X2=5.75 (DF=2) | 0.0563 |

|

| |||||

| Years in field (median (IQR)) | 6.25 (3, 16) | 6.25 (3, 16) | 4 (1.5, 10) | X2=6.56 (DF=2) | 0.0376 |

| Demographics at Time 2 (n=422) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Physicians (n=68 (16.1%)) | Nurses (n=149 (35.3%)) | Allied health (n=205 (48.6%)) | X2 | P | |

|

| |||||

| Age (n (%)) | X2=93.61 (DF=10) | <.0001 | |||

| 18–24 | 0 (0%) | 30 (21.6%) | 2 (1.0%) | ||

| 25–34 | 26 (47.3%) | 53 (38.1%) | 126 (65.3%) | ||

| 35–44 | 9 (16.4%) | 22 (15.8%) | 48 (24.9%) | ||

| 45–54 | 10 (18.18%) | 22 (15.8%) | 10 (5.2%) | ||

| 55–64 | 7 (12.7%) | 12 (8.6%) | 6 (3.1%) | ||

| 65+ | 3 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender (female) | 26 (46.4%) | 123 (90.4%) | 176 (92.6%) | X2=77.51 (DF=2) | <.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Familiarity with MoC | X2=43.51 (DF=4) | <.0001 | |||

| Not at all/to a slight extent | 5 (7.4%) | 37 (24.8%) | 17 (8.3%) | ||

| To a moderate extent | 27 (39.7%) | 75 (50.3%) | 74 (36.1%) | ||

| To a great/very great extent | 36 (52.9%) | 37 (24.8%) | 114 (55.6%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Years at org. (median (IQR)) | 4 (1.5, 8) | 5 (2, 11) | 3 (1, 7) | X2=7.60 (DF=2) | 0.0223 |

|

| |||||

| Years in field (median (IQR)) | 6 (3, 12) | 6 (2.75, 15) | 5 (1, 10) | X2=6.72 (DF=2) | 0.0347 |

| Demographics at Time 3 (n=448) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Physicians (n=72 (16.1%)) | Nurses (n=157 (35.0%)) | Allied health (n=219 (48.9%)) | X2 | P | |

|

|

|||||

| Age (n (%)) | X2=74.87 (DF=10) | <.0001 | |||

| 18–24 | 0 (0%) | 22 (16.2%) | 3 (1.6%) | ||

| 25–34 | 22 (44.0%) | 62 (45.6%) | 125 (64.4%) | ||

| 35–44 | 12 (24.0%) | 25 (18.4%) | 43 (22.2%) | ||

| 45–54 | 6 (12.0%) | 16 (11.8%) | 15 (7.7%) | ||

| 55–64 | 5 (10.0%) | 11 (8.1%) | 8 (4.1%) | ||

| 65+ | 5 (10.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

|

|||||

| Gender (% female) | 21 (42.9%) | 127 (92.7%) | 169 (88.5%) | X2=72.60 (DF=2) | <.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Familiarity with MoC | V | X2=23.06 (DF=4) | 0.0001 | ||

| Not at all/to a slight extent | 6 (8.3%) | 19 (12.1%) | 14 (6.4%) | ||

| To a moderate extent | 15 (20.8%) | 71 (45.2%) | 67 (30.6%) | ||

| To a great/very great extent | 51 (70.8% ) | 67 (42.7%) | 138 (63.0%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Years at org. (median (IQR)) | 3.5 (1, 7) | 5.25 (2, 14) | 3 (2, 7) | X2=8.30 (DF=2) | 0.0158 |

|

| |||||

| Years in field (median (IQR) | 6.25 (3, 16) | 6.25 (3, 16) | 4 (1.5, 10) | X2=16.40 (DF=2) | 0.0003 |

Note: MoC = Model of care

Note: X2 statistics for years at org. and years in field are Kruskal-Wallis chi-square statistics.

Note: Median (IQR) is median (25th quartile, 75th quartile).

Table 3:

ANOVA Results

| Scale | Predictor | DF | SS | MS | F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBPQ | Time | 2 | 12.38 | 6.19 | 8.90 | 0.0001 |

| Clinical role | 2 | 99.00 | 49.50 | 71.23 | <.0001 | |

| Familiarity | 2 | 38.24 | 19.12 | 27.51 | <.0001 | |

| Time*clinical role | 4 | 4.21 | 1.05 | 1.51 | 0.1960 | |

| EBPAS | Time | 2 | 1.83 | 0.91 | 1.70 | 0.1837 |

| Clinical role | 2 | 16.07 | 8.03 | 14.92 | <.0001 | |

| Familiarity | 2 | 28.84 | 14.42 | 26.79 | <.0001 | |

| Time*clinical role | 4 | 1.34 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.6450 | |

| OCRBS | Time | 2 | 20.56 | 10.28 | 24.58 | <.0001 |

| Clinical role | 2 | 23.16 | 11.58 | 27.68 | <.0001 | |

| Familiarity | 2 | 14.01 | 7.00 | 16.74 | <.0001 | |

| Time*clinical role | 4 | 1.99 | 0.50 | 1.19 | 0.3128 |

Abbreviations: EBPQ = Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire, EBPAS = Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale, OCRBS = Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale, DF = degrees of freedom, SS = sum of squares, MS = mean squares

Figure 2.

Key survey outcomes over time by clinician group. A: Evidence-based practice questionnaire. B: Evidence-based practice attitudes openness scale. C: Organizational change recipients beliefs scale.

Use of evidence-based practice (EBPQ):

EBPQ (range 1–5) scores were similar between Time 1 (adjusted meant1=3.55, standard error (SE)=0.05) and Time 2 (adjusted meant2=3.51, standard error (SE)=0.05), but greater at Time 3 compared to Time 2 (adj. meant3=3.64, SE=0.05; p=0.043). Physicians’ scores were higher than nurses’ (adj. meanphys=3.72, SE=0.06; adj. meannurse=3.23, SE=0.04; p<.0001), and allied health scores were also higher than nurses’ (adj. meanAH=3.76, SE=0.04; p<.0001, Supplemental Table 2).

Attitudes toward using evidence-based practice (EBPAS):

EBPAS (range 1–5) scores were similar over time. Physicians’ scores were lower than nurses’ (adj. meanphys=3.46, SE=0.06; adj. meannurse=3.74, SE=0.04; p<.0001), and physicians’ scores were also lower than allied health (adj. meanAH=3.81, SE=0.03; p<.0001).

Acceptance of the new translational research model of care (OCRBS):

OCRBS (range 1–5) scores were lower at Time 2 compared to Time 1 (adj. meant1=3.44, SE=0.04; adj. meant2=3.19, SE=0.04; p<.0001), and then higher at Time 3 (adj. meant3=3.51, SE=0.04; p<.0001). Scores did not differ significantly between Times 1 and 3. Physicians had the lowest scores (adj. meanphys=3.18, SE=0.05), followed by allied health (adj. meanAH=3.34, SE=0.03), with nurses having the highest scores (adj. meannurse=3.62, SE=0.03) (p range <.0001–0.003).

Results of Open-Ended Questions

Results from the open-ended questions are presented in Table 4. At Time 1, the most frequent opinion expressed was a lack of information and understanding about the new translational research model of care. This theme included comments related to preparedness, training, orientation, and mentorship. The second most common theme reported at Time 1 related to the challenges presented by the move to the new facility, including concerns related to the space and transition. Importantly, clinicians reported being excited and optimistic about implementing the new model of care and moving to a state-of-the-art facility.

Table 4:

Counts of the number of times each theme is mentioned in responses to the open-ended questions at times 1, 2, and 3. There was one question asked at Time 1, and three open-ended questions asked at Times 2 and 3.

| Theme | Question | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Lack of information/understanding, preparedness, need more orientation, training, or mentorship | Q1a | 21 | 8 | 8 |

| Q2b | 2 | 3 | ||

| Q3c | 21 | 15 | ||

|

| ||||

| Challenges presented by physical move to new facility | Q1 | 15 | 12 | 6 |

| Q2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q3 | 10 | 3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Excitement about transition to new state-of-the art physical structure and new technology and equipment | Q1 | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Q2 | 55 | 9 | ||

| Q3 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Challenges presented by transition to new model of care and organizational structure | Q1 | 10 | 13 | 10 |

| Q2 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Q3 | 34 | 28 | ||

|

| ||||

| Clinicians feel their input is not valued by leadership and researchers, contributing in part to lack of transparency | Q1 | 10 | 6 | 1 |

| Q2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q3 | 3 | 2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Unequal distribution of resources and work between departments, floors, sites, and different roles leads some to feel left out | Q1 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| Q2 | 3 | 13 | ||

| Q3 | 10 | 32 | ||

|

| ||||

| Optimism for the new model of care and organizational changes | Q1 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Q2 | 40 | 104 | ||

| Q3 | 2 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Clinicians need protected time to engage activities outside of clinical care | Q1 | 6 | 8 | 11 |

| Q2 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Q3 | 23 | 27 | ||

|

| ||||

| Challenges to communication and collaboration between clinicians and researchers | Q1 | 4 | 11 | 10 |

| Q2 | 7 | 6 | ||

| Q3 | 38 | 74 | ||

|

| ||||

| Understaffed, overworked, lack of work/life balance, burnout, high turnover, stress | Q1 | 4 | 20 | 5 |

| Q2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q3 | 22 | 8 | ||

|

| ||||

| Challenges presented by new technology in state-of-the art clinical facility | Q1 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Q2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Q3 | 8 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Concerns about promotion/marketing of new hospital | Q1 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Q2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q3 | 0 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Challenges to communication and collaboration between clinical disciplines | Q1 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| Q2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q3 | 12 | 10 | ||

|

| ||||

| Structured opportunities facilitate clinical research collaboration | Q1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q2 | 7 | 20 | ||

| Q3 | 0 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Good communication/collaboration between clinicians or other non-research staff | Q1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q2 | 29 | 40 | ||

| Q3 | 0 | 0 | ||

Q1: “If you have other feedback on the transition to the SRAlab, please share.”

Q2: “What aspects of the transition to the new model of care have gone well?”

Q3: “What suggestions do you have to improve the transition to the new model of care?”

At Time 2, 7–9 months after the move, excitement about the new state-of-the-art structure peaked and optimism for the new model of care grew stronger. However, clinicians continued to describe challenges related to implementation of the new model of care (e.g., adapting to the physical structure with researchers in clinical space, integration of specific EBP roles in new organizational structure), as well as challenges related to communication and collaboration with researchers (e.g., increased staff available to allow time for collaboration, need for flexible clinical schedules to allow attending research presentations). Clinicians also described their need to have more time to engage in research and other professional growth activities in addition to providing traditional clinical care.

At Time 3, 2.5 years after the hospital transition, the most common theme was optimism for the new AbilityLab Model of Care. While many clinicians reported feeling optimistic, challenges to communication and collaboration with researchers remained. Additionally, clinicians from several departments perceived that an unequal distribution of resources across departments led to fewer opportunities to become as involved in research compared to other departments.

DISCUSSION

Healthcare organizations encounter multiple challenges dealing with an ever-evolving, data-driven environment. The dramatic transition of our organization created a unique opportunity to study responses to physical and team-focused changes within the organization. While clinicians perceived the move to a new, state-of-the-art facility as exciting, the accompanying cultural changes, particularly communication and collaboration between clinicians and researchers, created challenges that took over two years to resolve. Addressing these challenges required multi-factorial implementation strategies going beyond the physical structure changes to target team roles with leadership, champions, and clinician incentives.

The changes resulting from the transition period negatively affected clinicians’ acceptance of the change, measured by the OCRBS, up to 9 months after the move. Data from open-ended questions at the second survey suggests that the clinicians’ difficulties related to communication and collaboration with researchers, lack of supported time to engage in research, and feeling understaffed and overworked. Interestingly, despite these concerns, the transition did not result in negative attitudes toward EBP or their use of EBP principles.

At the third survey, 2.5 years after the move, the acceptance of the transition had recovered, and self-reported use of EBP was greater. Responses to open-ended questions revealed greater optimism for the translational model of care. This optimism may have been due, in part, to the fact that, between the second and third surveys, leadership implemented an employee engagement initiative for all disciplines, a professional development structure program for allied health clinicians, and opportunities for clinical-research communication. Both supportive leadership and fair application of organizational incentives have been suggested to be important factors to overcome long-term resistance to organizational change.30 Thus, the executive leadership team spearheaded and expanded initiatives during the transition to promote clinician and research engagement. Examples include collaborative internal grant funding opportunities, shadowing their counterparts, lunch and learn events, and social and educational gatherings. 12

Two common challenges of clinician-research partnerships are gaining effective buy-in of clinicians and minimizing communication barriers between clinicians and researchers.6 The organization used evidence-based implementation strategies to address these challenges. Physical structure changes to address these challenges included locating clinicians and researchers in the same space to enhance communication and form partnerships, an evidence-based implementation strategy.31 Team-focused changes also enhanced clinically relevant research.2,6 These strategies included enhancing a professional development structure to engage more clinicians in the early stages of research or their own projects. Engaging clinicians earlier in the research process to co-create research protocols and products is a key implementation strategy to improve translational research, rather than passively disseminating research findings to clinicians.32

33 Physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals differed on the OCRBS, EBPQ, and EBPAS; these differences deserve exploration in future research as all disciplines play critical roles in rehabilitation medicine (Figure 1). In our sample, resident and attending physicians tended to have the lowest acceptance of the organizational change on the OCRBS and the least positive attitudes toward EBPs. However, they and allied health professionals reported using the principles of EBP to a greater extent than did nurses. Interestingly, nurses had the highest acceptance of the organizational changes measured by the OCRBS despite being the profession with the least familiarity with the goals of the AbilityLab Model of Care. Implementation strategies must be tailored to each specific discipline to adequately reflect their roles and responsibilities.34,35,36 37,35,38

Enhancing patients’ function is a historic focus of rehabilitation research that can be optimized by engaging clinicians in the research enterprise.39 The transition to the new translational research hospital provided opportunities to drive clinically-relevant rehabilitation research innovations. It also provided an opportunity to enhance clinical implementation of EBPs as a part of the AbilityLab Model of Care, which may be related to the observed improvements in EBPQ. Clinician-scientists, who become actively involved in research can accelerate the use of research evidence, generate new relevant research questions, and ensure that rehabilitation rises to meet the needs of today’s consumer.2,5,39,40 These goals are supported by enabling clinicians to have first-hand experiences with research and providing research mentorship.6 These team-focused strategies rely on collaborative communication between researchers, clinicians, and patients.41,42

Our OCRBS survey results and qualitative data are consistent with the authors’ experiences of transitioning to the new facility. Although many challenges related to the physical move and cultural changes resolved over time, some cultural challenges remained after 2.5 years in the new facility. Since Survey 3, we have created additional opportunities for clinician-research training and funding for clinician-driven research projects to further break down barriers and enhance collaborative research to the benefit of our patients. The COVID-19 pandemic required remote working arrangements for many researchers, limited in-person contact with clinicians and patients, and reconsideration of open workspace environments, which can be studied in the future.

Limitations

We recognize limitations resulting from the study design. We preserved anonymity by not collecting identifiers, which prevented repeated measures analyses that would have higher precision and statistical power. The repeated cross-sectional analysis prevents us from drawing conclusions about within-subjects change over time, and instead tells us about the participants’ reported beliefs and use of EBP at three distinct time periods. An additional limitation is that we used abbreviated adapted versions of the EBPQ, EBPAS, and OCRBS. We validated these measures in our earlier work as a pragmatic approach to allow a high degree of data collection with minimal participant burden.18 However, these adaptations introduced potential risk of bias as we selected questions that the research team thought would be most relevant to our context. We did not include a validated measure of interdisciplinary communication, which limits our ability to comment on how the different groups perceived their communication with each other, or researchers.

Conclusions

Although moving to a new facility shifted the culture of the organization in intended and unintended ways, some of which created challenges requiring more than two years to abate, it did not impair favorable attitudes or use of EBP. Implementation strategies related to the physical transition including new architecture, organizational processes that utilized champions, leadership structure, and professional development opportunities may have been associated with greater reported EBP use by the end of the study. Future research should determine the most effective strategies, in isolation if possible, over longer timeframes, as well as discipline-specific approaches to enhancing translational research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement of any presentation of this material:

• Preliminary analyses of the first year’s data were presented in a symposium at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine in October 2017, with the final data published to validate the measurements at time 1 was published in BMC Health Services Research by Smith et al, 2020 (DOI: 10.1186/s12913-020-05118-4).

• Preliminary analyses of the three-year results were presented at the APTA’s Center on Health Services Research and Training Summer Institute as a virtual meeting platform presentation (May 21, 2020), as a virtual poster presentation at Academy Health conference (June 2020), in a virtual symposium at American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (September 2020), and at an in-person symposium at American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (November 2022).

Acknowledgement of financial support:

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, for MR by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Advances in Rehabilitation Research and Training Grant (H133P130013); the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (F32 HS025077), the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging (P30AG059988), and for RL by Research Career Scientist Award (Number IK6 RX003351 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation R&D (Rehab RD) Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the organizations.

Abbreviations

- EBP

Evidence-based practice

- SRAlab

Shirley Ryan AbilityLab

- EBPQ

Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire

- EBPAS

Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale

- OCRBS

Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- SAS

Statistical Analysis System

- Phys

Physicians

- AH

Allied health

Footnotes

In Memoriam: The authors are indebted to the vision and leadership of Dr. Joanne Smith who oversaw the transition of the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago to the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare salary from the organization (see affiliations) studied in the article. AH is a former board member of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. PH reports travel support from the University of Illinois at Chicago. RL reports travel support by the target organization, as well as being a Scientific Advisory Board member of SpineX, Inc, and a Scientific Advisor of the KITE Research Institute of UHN, Toronto ON, Canada, and has received in kind donations by Celgene, Inc and Allergan, with no other relevant conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones ML, Cifu DX, Backus D, Sisto SA. Instilling a research culture in an applied clinical setting. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Jan 2013;94(1 Suppl):S49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin SH, Murphy SL, Robinson JC. Facilitating evidence-based practice: process, strategies, and resources. Am J Occup Ther. Jan-Feb 2010;64(1):164–71. doi: 10.5014/ajot.64.1.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheets PL, Hornby TG, Perry SB, et al. Moving Forward. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2021;45(1):46–49. doi: 10.1097/npt.0000000000000337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jette AM. Moving Research From the Bedside Into Practice. Phys Ther. May 2016;96(5):594–6. doi: 10.2522/ptj.2016.96.5.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blevins D, Farmer MS, Edlund C, Sullivan G, Kirchner JE. Collaborative research between clinicians and researchers: a multiple case study of implementation. Implement Sci. Oct 14 2010;5:76. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen T, Henn G. The Organization and Architechture of Innovation: Managing the Flow of Technology. Routledge; 2007:136. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabo F, Hwang Y, Levenstein M, Owen-Smith J. Shared Paths to the Lab:A Sociospatial Network Analysis of Collaboration. Environment and Behavior. 2015;47(1):57–84. doi: 10.1177/0013916513493909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reagans R. Close Encounters: Analyzing How Social Similarity and Propinquity Contribute to Strong Network Connections. Organization Science. 2011;22(4):835–849. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cranley LA, Cummings GG, Profetto-McGrath J, Toth F, Estabrooks CA. Facilitation roles and characteristics associated with research use by healthcare professionals: a scoping review. BMJ open. Aug 11 2017;7(8):e014384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long JC, Cunningham FC, Braithwaite J. Bridges, brokers and boundary spanners in collaborative networks: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. Apr 30 2013;13:158. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. Aug 7 2015;10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.VonBehren D, Killion MM, Burke C, Finkelmeier B, Zamora B. Planning, Designing, Building, and Moving a Large Volume Maternity Service to a New Labor and Birth Unit: Commentary and Experiences of Experts. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. Nov/Dec 2016;41(6):332–339. doi: 10.1097/nmc.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comeau OY, Armendariz-Batiste J, Baer JG. Preparing Critical Care and Medical-Surgical Nurses to Open a New Hospital. Crit Care Nurs Q. Jan/Mar 2017;40(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/cnq.0000000000000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, Hurlburt MS. Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): a randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implement Sci. Jan 16 2015;10:11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0192-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gale NK, Shapiro J, McLeod HS, Redwood S, Hewison A. Patients-people-place: developing a framework for researching organizational culture during health service redesign and change. Implement Sci. Aug 20 2014;9:106. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0106-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brewster AL, Curry LA, Cherlin EJ, Talbert-Slagle K, Horwitz LI, Bradley EH. Integrating new practices: a qualitative study of how hospital innovations become routine. Implement Sci. Dec 5 2015;10:168. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0357-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JD, Rafferty MR, Heinemann AW, et al. Pragmatic adaptation of implementation research measures for a novel context and multiple professional roles: a factor analysis study. BMC Health Serv Res. Mar 30 2020;20(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05118-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. Oct 2 2013;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An Extension of RE-AIM to Enhance Sustainability: Addressing Dynamic Context and Promoting Health Equity Over Time. Front Public Health. 2020;8:134. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. The Implementation Research Logic Model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci. Sep 25 2020;15(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. Dec 1 2013;8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Upton D, Upton P. Development of an evidence-based practice questionnaire for nurses. J Adv Nurs. Feb 2006;53(4):454–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Ment Health Serv Res. Jun 2004;6(2):61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armenakis AABJ, Pitts JP, Walker HJ. Organizational Change Recipients Beliefs Scale: Development of an Assessment Instrument. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2007;42:481–505. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JD, Rafferty MR, Heinemann AW, et al. Pragmatic adaptation of implementation research measures for a novel context and multiple professional roles: a factor analysis study. BMC Health Services Research. 2020/03/30 2020;20(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05118-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/ACCESS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. Nov 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones SL, Van de Ven AH. The Changing Nature of Change Resistance:An Examination of the Moderating Impact of Time. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2016;52(4):482–506. doi: 10.1177/0021886316671409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weaver AL, Hernandez S, Olson DM. Clinician Perceptions of Teamwork in the Emergency Department: Does Nurse and Medical Provider Workspace Placement Make a Difference? J Nurs Adm. Jan 2017;47(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawson R. Pragmatic trials and implementation science: grounds for divorce? BMC Med Res Methodol. Aug 16 2019;19(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0814-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arumugam V, MacDermid JC, Walton D, Grewal R. Attitudes, knowledge and behaviors related to evidence-based practice in health professionals involved in pain management. Int J Evid Based Healthc. Jun 2018;16(2):107–118. doi: 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. Winter 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinemann AW, Nitsch KP, Ehrlich-Jones L, et al. Effects of an Implementation Intervention to Promote Use of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures on Clinicians’ Perceptions of Evidence-Based Practice, Implementation Leadership, and Team Functioning. J Contin Educ Health Prof. Spring 2019;39(2):103–111. doi: 10.1097/ceh.0000000000000249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raeissadat SA, Bahrami MH, Rayegani SM, et al. Obstacles facing evidence based medicine in physical medicine and rehabilitation: from opinion and knowledge to practice. Electron Physician. Nov 2017;9(11):5689–5696. doi: 10.19082/5689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore JL, Carpenter J, Doyle AM, et al. Development, Implementation, and Use of a Process to Promote Knowledge Translation in Rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Jan 2018;99(1):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.08.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiao S, Li X, Zhou Y, Shen Z, Stanton B. Attitudes toward evidence-based practices, occupational stress and work-related social support among health care providers in China: A SEM analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Backus D, Jones ML. Maximizing research relevance to enhance knowledge translation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Jan 2013;94(1 Suppl):S1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, Bent C. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthc (Amst). Mar 2016;4(1):11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manojlovich M, Squires JE, Davies B, Graham ID. Hiding in plain sight: communication theory in implementation science. Implement Sci. Apr 23 2015;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0244-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Halloran R, Grohn B, Worrall L. Environmental factors that influence communication for patients with a communication disability in acute hospital stroke units: a qualitative metasynthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Jan 2012;93(1 Suppl):S77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.