Abstract

Pressure injuries affect 1 to 46% of residents in aged care (long term) facilities and cause a substantial economic burden on health care systems. Remote expert wound nurse consultation has the potential to improve pressure injury outcomes; however, the clinical and cost effectiveness of this intervention for healing of pressure injuries in residential aged care require further investigation. We describe the remote expert wound nurse consultation intervention and the method of a prospective, pilot, cluster randomised controlled trial. The primary outcome is number of wounds healed. Secondary outcomes are wound healing rate, time to healing, wound infection, satisfaction, quality of life, cost of treatment and care, hospitalisations, and deaths. Intervention group participants receive the intervention over a 12‐week period and all participants are monitored for 24 weeks. A wound imaging and measurement system is used to analyse pressure injury images. A feasibility and fidelity evaluation will be concurrently conducted. The results of the trial will inform the merit of and justification for a future definitive trial to evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of remote expert wound nurse consultation for the healing of pressure injuries in residential aged care.

Keywords: aged care, implementation research, pilot randomised controlled trial, pressure ulcer, protocol

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Pressure injuries (PIs), also known as pressure ulcers, are a common chronic wound 1 caused by sustained mechanical deformations applied to the skin and underlying tissues. 2 PIs cause pain and suffering, predispose the person to infection, may require lengthy hospital stay, and can lead to premature death in vulnerable individuals. 3 PIs affect between 1 and 46% of residents in aged care facilities 4 and from January to March 2022, 9% of Australian residential aged care recipients (n = 10 403) experienced one or more PIs, a statistic that has been unacceptably high over the last 3 years. 5 In Australia, aged care residents who have PIs and require hospitalisation contribute to the estimated AU$9.11 billion cost of PIs in acute care. 6 This outcome is particularly concerning given a greater per capita incidence than has been reported in both the United States and the United Kingdom. 7 , 8

The International Guidelines for pressure injury prevention and management 3 provide guidance for the assessment, care and monitoring of people who have PIs. Clinical guidelines are primarily operationalised by nurses in residential aged care, in collaboration with personal care workers, physicians and allied health care professionals. 9 However, the ongoing issue of PIs among people living in residential aged care suggests a gap between what is recommended as best and actual care. This evidence to practice gap was highlighted in an Australian Government Royal Commission that inquired into aged care quality and safety from 2019 to 2021. 10 , 11 Suggested reasons for sub‐optimal care included variable expertise among aged care nurses and personal care workers, high turnover of staff and fragmented and untimely access to expert wound nurses. 10 Notably, the interim and final report of the Commission reported that residents had experienced preventable PIs, the deterioration of existing PIs, pain, and suffering, and death. 10 , 11 The need to harness the input of expert wound management clinicians, to generate high quality care and optimal resident outcomes, was recommended as critical steps forward in achieving better outcomes for people with PIs. 10

Wound Management Clinical Nurse Consultants (WCNCs) bring expert clinical advice, education and support to the care of people who have PIs. Importantly, WCNCs can build capacity for excellence among the care team by working directly with patients, health care providers and families. The impact of the work of nurse consultants on patient outcomes include better wound treatment and higher levels of satisfaction as reported among patients receiving nurse consultation compared with those who do not. 12 A nurse consultant led practice change reported improved uptake and adherence to pressure injury risk screening in home care. 13 A randomised controlled trial comparing wound consultations to usual care for leg and foot ulcer patients identified a positive healing rate of 6.82% per week in the intervention group compared with a negative rate of −4.90% per week in the control group (P = .012). This achieved an estimated treatment cost difference between the groups at 12 months of AU$191,935 less in the intervention group. 14 A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials and before and after studies evaluating the effectiveness of telemedicine for ‘distant wound care advice’ reported significant improvement in wound healing (RR 1.50, CI 1.06 to 2.13, P = .02). 15

Cost effectiveness evaluations are essential when estimating the cost of new interventions, 16 for example, models that involve implementation of evidence‐based practice guidelines and approaches to treatment and care. The direct impact of WCNCs on PI management cost in residential aged care has not been comprehensively described. In an earlier residential aged care cost modelling study, 17 we applied a WCNC informed evidence‐based practice costing model and identified that the cost to healing for 21 residents with 23 PIs would be similar (AU$99,693) to the actual treatment costs of the sample so far, noting that the actual cost was ongoing given that only 19 of the 23 PIs had healed during the study. More broadly, there is compelling evidence that PI costs can reduce if best practice is achieved. 7 , 18 , 19

The involvement of WCNCs in the management of aged care residents has the potential to improve PI outcomes and optimise care provision; however, the clinical and cost effectiveness of WCNC consultations for healing of PIs require further investigation.

1.2. Research preceding this pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT)

Our wider program of research includes a non‐randomised feasibility study (the commencement of which precedes the start of the pilot RCT) to ascertain if consultation with a remote expert wound nurse (our intervention) is acceptable and feasible in an aged care organisation and if intervention fidelity can be achieved. Feasibility is conceptualised where ‘all or parts of the intervention to be evaluated and other processes to be undertaken in a future trial is/are carried out (piloted) but without randomisation of participants’. 20 The full results of the feasibility study will be elsewhere reported; however, aspects pertinent to understanding the context of the pilot RCT described in this paper are provided.

The feasibility study and the pilot RCT are being conducted in the same residential aged care organisation with different facilities (referred to as ‘Homes’) participating in each study. Nursing staff do not typically work across different Homes and this has been the case in the feasibility study. The intervention has been implemented in the feasibility study in 2022. WCNCs (two consultants who job share a full time position) were used for the feasibility study and the pilot RCT. For the pilot RCT, the WCNCs fill the role of Research Nurse when interacting with control site Homes.

Resources and processes required for the RCT were developed and tested in the feasibility study. A ‘Home Champions’ training program for nurses was developed and 30 nurses trained to participate. Their feedback and our experiences led to refinements to the training program to better suit the context. A pre‐recorded video‐presentation about the project was developed for viewing by residents and their family members and modified in line with consumer and health care provider feedback before being finalised. A clinical manual was purpose designed and produced for the WCNCs, nurses and managers at the Homes to guide processes associated with consultations, wound imaging and data collection. Protocols for PI imaging and data collection were refined throughout the feasibility study in preparation for the pilot RCT.

In total, 40 aged care residents were recruited to participate in the feasibility study (24 who had a PI and 16 who were at high risk of developing a PI). The WCNC consultations and data collection is ongoing; however, to date, 127 consultations have been completed with residents, nurses, and in some cases also with family members. The ‘bed‐side’ data collection completed by the nurses in the feasibility study are similar to that which is required for the pilot RCT; therefore, data collection processes have been tested in preparation for the trial. In person and unannounced checking of alignment of the WCNC care plan to the actual care provided to residents in the feasibility study has been favourable. In the case of the 15 feasibility study residents who were participating at the time of inspection, all except one was receiving PI treatment as per the care plan formulated by the WCNC.

Implementation research can help to reduce research waste by identifying approaches that support translation of evidence into practice. 21 Our program of research provides the opportunity to evaluate the likelihood of successfully implementing the intervention in our feasibility study and also in the pilot RCT. The later study enables evaluation of the acceptability, feasibility, and fidelity of trial processes. By assessing intervention and research processes across both the feasibility study and pilot RCT, we are amassing a comprehensive evidence base to inform future research. Aspects of implementability evaluated in the feasibility study will be elsewhere described and reported.

1.3. Aims

The aim of this paper is to describe the intervention and the design of our pilot RCT. The pilot RCT commenced recruitment on 8 September 2022 and recruitment was ongoing at the time of submission of this paper. Our future trial, if justifiable after completion of the pilot RCT, will evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of remote expert wound nurse consultation for the healing of PIs in residential aged care.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Trial registration

The trial was prospectively registered on 1 September 2022 in the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, reference ACTRN12622001180707. https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=384579&isReview=true

2.2. Study design

Prospective, pilot and parallel cluster randomised controlled trial. The unit of randomisation is the Home with a 1:1 allocation ratio of participants. We define a pilot randomised controlled trial as a study ‘in which the future RCT, or parts of it, including the randomisation of participants, is conducted on a smaller scale (piloted) to see if it can be done’. 20 The pilot RCT will test RCT procedures however will not test hypotheses, efficacy, or effectiveness as these are not evaluated in pilot RCT methodology. 22 , 23 The pilot RCT will align with the CONSORT 2010 extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. 23

2.3. Site

Regis Aged Care is one of Australia's largest providers of aged care services with over 6000 residents living in 64 Homes across the country. The six Homes participating in the pilot RCT are located in Victoria and two each are located in metropolitan, regional and rural areas.

2.4. Resident participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria:

Equal to or greater than 18 years of age;

Has one or more PI;

Is a resident of a participating Home;

Is expected to be living in the Home for the 12‐week intervention period.

Exclusion criteria:

Receiving palliative care and/or whose passing (death) is expected to be imminent.

2.5. Care of all participants

All participants (intervention and control group) will be cared for by Home staff as usual during the study period. This includes PI risk screening, skin inspection, skin care, wound treatment, and PI prevention interventions such as regular repositioning and the use of alternating air mattresses if indicated. Nurses may be titled ‘registered’ or ‘enrolled’, the former having a higher qualification and scope of practice than the latter in Australia. Personal care workers are involved in skin care and turning and positioning residents and do not undertake PI treatment. The organisation has an extensive formulary of wound dressings (which are supplied at no cost to the resident); however, a supply of wound dressings and devices (Mölnlycke Health Care) will be made available at all participating Homes during the trial (free of charge) to ensure that wound treatment can always be initiated immediately as intended (e.g., to avoid any supply issues). These wound dressings and devices include those usually available at the Homes (e.g. silicone dressings and antimicrobial dressings) as well as turning and positioning devices and heel boots.

A commercial wound imaging and measurement system, Tissue Analytics will be used to analyse PI images. PI images will be taken by the nurses at the Home with an Apple iPad (Apple Inc., Cupertino, California) or digital camera (facility owned and operated). All image data in Tissue Analytics will be stored in Amazon Web Services; Amazon Web Services complies with Australian data privacy compliance. The images and data will be available to nurses at the participating Homes via digital PDF reports attached to the residents electronic medical record and via the online Tissue Analytics portal.

2.6. Intervention

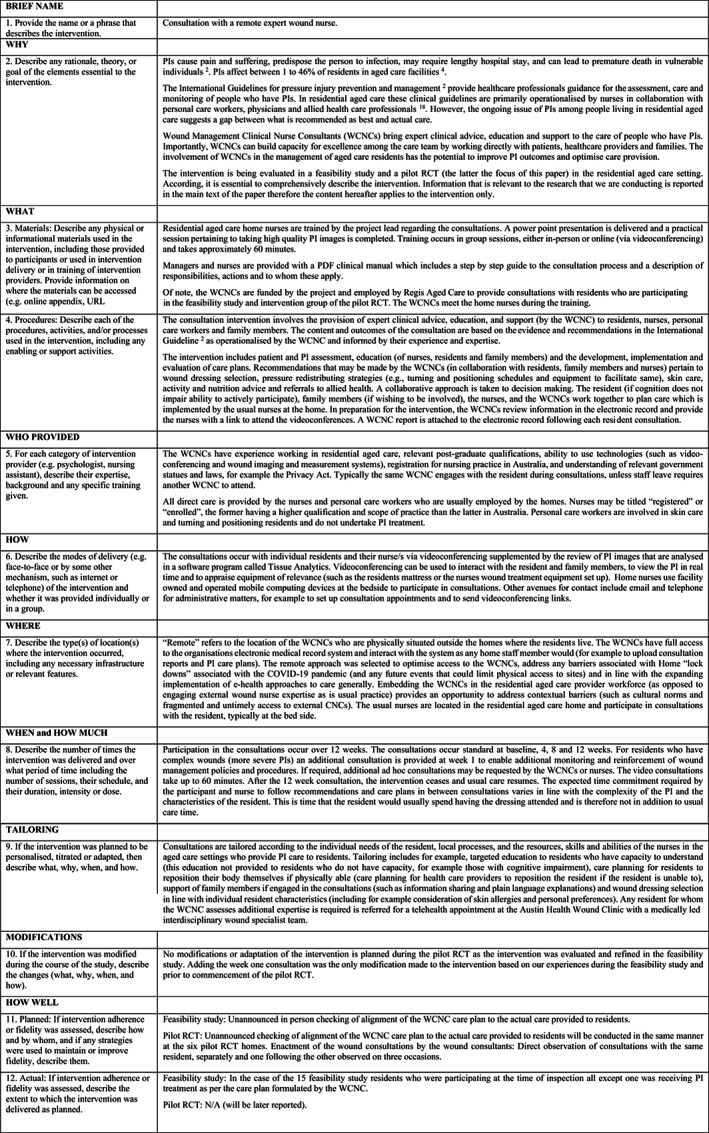

The intervention is consultation with a remote expert wound nurse. The WCNCs are funded by the project and used by Regis Aged Care to provide expert clinical advice, education and support to intervention group residents and their nurses, personal care workers and family members. The content and outcomes of the consultation are based on the evidence and recommendations in the International Guideline 3 as operationalised by the WCNC and informed by their experience and expertise. Participation in the consultations occur over 12 weeks, at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks from consent to participate. If required, additional ad hoc consultations may be requested by the WCNCs or nurses. After the 12 week consultation, the intervention ceases and usual care resumes. Further detail of the intervention is shown in the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist 24 in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (references cited in this figure are given in Endnotes).

2.7. Usual care

Home nurses engage with external wound nurses (via consultancy paid for by the Homes, not the resident) as they deem necessary for individual residents. External consultations may occur in‐person at the Home or via email or telephone. The frequency of consultations varies. Residents may receive one or more consultations, depending on the need as assessed by the nurse and/or external consultant and the external consultants availability. This engagement with external WCNCs will continue as usual at control Homes.

2.8. Home staff training and support

Nurses are trained regarding the consultations, trial processes, data collection, for taking high quality PI images, and for event reporting and reinforcement of usual care processes (e.g., escalation of concerns about a resident's PI). Training occurs in separate group sessions for the intervention and control group Home staff, either in‐person or online via videoconferencing. Managers and nurses are provided with the clinical manual for reference and the intervention Home manual provides a step by step guide to the consultation process. Support is provided by the WCNCs to the intervention group Home staff and these WCNCs also act as Research Nurses to support control group Home staff with respect to imaging and data collection. Different email signatures and contact information are provided so that the role of WCNC or Research Nurse is communicated to Home staff as is applicable.

2.9. Sample size

The sample size for the pilot RCT has been informed by published guidelines 25 and accounts for pragmatic factors such as the anticipated number of residents with a PI (as informed by reviewing PI incidence data at Regis Aged Care over several years) and the conduct of the study during the COVID‐19 pandemic (which created significant pressures on aged care services in Australia). No power‐based sample size calculation was undertaken; however, a sample of 80 residents (n = 40 per group) was proposed by the research team which includes experts in clinical trial design.

2.10. Randomisation

The selection of study sites (Homes) was based on the anticipated number of residents with PIs, geographic diversity (metropolitan, regional, and rural areas), and with consideration of concurrent project commitments at Homes. Three Homes were randomly allocated to be intervention sites and three Homes to be control sites. A randomisation table was created by computer software (i.e., computerised sequence generation) and the randomisation was completed by a person independent of the trial.

2.11. Screening, recruitment and consent

All residents at participating Homes will be screened for eligibility by the WCNC/Research Nurse using information from the electronic medical record. Potentially eligible participants will be shortlisted and nurses from the Homes will advise if the resident consents for self or if a responsible person should provide consent. Language spoken by the resident or person responsible is also ascertained and if requiring an interpreter, this is arranged. If potentially eligible, the WCNC/Research Nurse will contact the consenting person and provide the Participant Information Sheet and Consent Form (either by post or email). Opportunity to ask questions will be provided. The resident will be considered a participant from the date of written consent.

2.12. Participant monitoring

All participants are monitored for a total of 24 weeks. During this time period PI images are taken weekly. In the case of the intervention group, the consultations with the WCNC cease at 12 weeks.

2.13. Outcomes and data collection

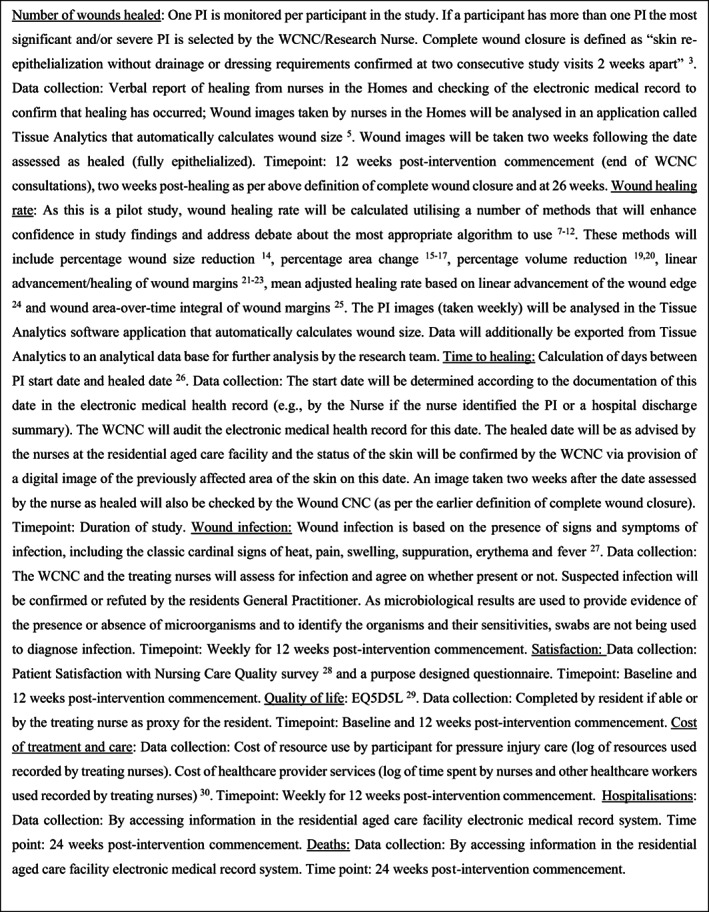

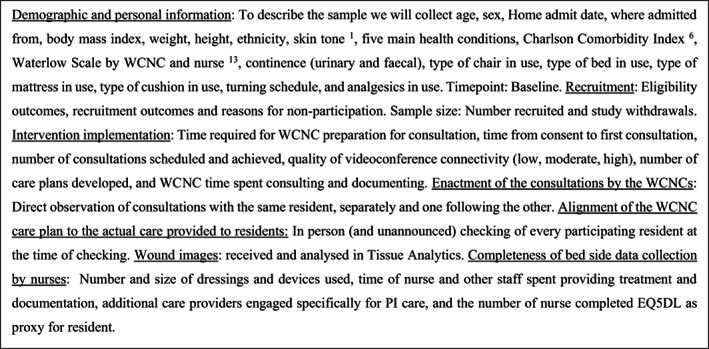

The primary outcome of the study is number of wounds healed. Secondary outcomes are wound healing rate, time to healing, wound infection, satisfaction, quality of life, cost of treatment and care, hospitalisations, and deaths. Further description of these outcomes and the approaches to data collection are shown in Figure 2. We will collect demographic and personal information to describe the sample and data for our feasibility and fidelity evaluation including recruitment outcomes, intervention implementation, enactment of the consultations by the WCNCs, alignment of the WCNC care plan to the actual care provided to residents, wound images received and analysed, and the completeness of bed side data collection by nurses. Further description of these outcomes and the approaches to data collection are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Primary and secondary study outcomes and data collection (references cited in this figure are given in Endnotes).

FIGURE 3.

Other outcomes and data collection (references cited in this figure are given in Endnotes).

2.14. Analysis

Data analysis will be conducted in accordance with a pre‐determined data analysis plan which has been reviewed by a Statistical Consulting Centre. Data will be entered directly into a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) database (Version 26.0, IBM). A validation of 10% of data will be undertaken. The person conducting the analysis will not be aware which participants are from the intervention and control Homes.

Parametric and non‐parametric measures will be used to compare the intervention and control groups at baseline to assess the effectiveness of randomisation to achieve comparable groups. Examination of the number of healed wounds in addition to days to healing will be analysed using a Cox's Proportional Hazard model. Analysis of wound healing rate will be analysed using a two‐way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Change in wound measurements will be examined using paired samples t tests and one way repeated measures ANOVA. Examination of the number of healed wounds in addition to days to healing will be analysed using a Cox's Proportional Hazard model. Analysis will be in accordance with intention‐to‐treat with additional consideration of a ‘complete case’ analysis. Cases lost to follow up shall be assumed to have nil change to wound size. Average wound size change shall be imputed between time points for missed data. A ‘modified intention‐to‐treat’ analysis will also be conducted to indicate of the effects associated with the treatment.

The study will report results pertaining to participant satisfaction and EQ‐5D‐5L subdomain responses (mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression). 26 An Australia‐specific value set reflecting the general public's health preferences will be applied to EQ‐5D‐5L responses to estimate the health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), 27 which is a measure of consumer perspectives of their health status, with a score of 1.0 indicating perfect health and a score of 0.0 indicating death. 28 HRQoL scores will be further combined with length of time to derive quality‐adjusted life year (QALY) weights as the health outcome measurement in economic modelling. 29

This study will use a micro‐costing approach 16 to its economic evaluation from an Australian health care system perspective. In this approach, all costs associated with equipment, dressings, and time during assessment, care, consultations and referrals are recorded, as well as costs associated with the remote consultation intervention. Indictive costs associated with treatments in alternate settings such as acute care admissions will be referenced from local and national sourced estimates as used in similar Australian‐based PI economic modelling. 30 An incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) will be calculated as the ratio of the average differences in costs to the average differences in QALYs between intervention and control group participants. A cost‐effectiveness threshold is defined as a reference of the maximum cost per health outcome that a health system is willing to pay. 31 The estimated ICER will be compared with a threshold of $100 000 per QALY (as in similar Australian‐based PI economic modelling) to provide an indication of cost‐effectiveness of the intervention contextualised to its cost and health outcome.

As per the overview of economic modelling published by Padula, Lee, and Pronovost, 28 this study will additionally report a budget impact analysis where the results from the local study setting/data are extrapolated to a broader population (in this instance, this will be the Australian national context) as well as reporting a return on investment which signals the time taken until the expended costs for the intervention are recouped through cost savings gained through improved quality and efficient health care. Mixed effects, multiple level (including location as a covariate to specify any clustering effects), logistic regression modelling predicting healed PIs will be used using a 12‐week horizon given that time in motion logs are maintained for 12 weeks and not the 24‐week follow‐up period.

3. DISCUSSION

PIs have a significant impact on the resident, are concerning for relatives, place considerable demand on health care providers, and present a major economic burden on health care systems. PIs are prevalent in residential aged care and poor outcomes must be avoided to ensure that aged care residents live the latter years of their lives without unnecessary pain and suffering and so that health care cost in minimised.

The approach of remote expert wound nurse consultation is essential to enable future scalability, if proven to be effective, particularly in the light of the restrictive effect that the COVID‐19 pandemic has had on the provision of in‐person care. Furthermore, in locations like Australia, where geographic distance stymies access to health care services, remote approaches to care may offer a feasible solution when barriers to in person care are not transient or avoidable.

This pilot RCT of remote expert wound nurse consultation for healing of PIs in residential aged care will yield information to inform the merit of and approach to conducting a future definitive trial to evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of the intervention for healing of PIs in residential aged care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

SK has received research funds for investigator initiated studies and has been invited by Mölnlycke Health Care to speak at conferences and symposia.

NS and AG are consultants to Mölnlycke Health Care, members of its Global Pressure Ulcer/Injury Advisory Board and have received research funds from Mölnlycke. Mölnlycke has not controlled (or regulated) the research carried out by NS and AG.

BP declares Personal Fees and Equity Holdings with Monument Analytics, LLC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a competitive grant from the Victorian Medical Research Acceleration Fund, with funding co‐contribution from the Department of Nursing at the University of Melbourne, the Melbourne Academic Centre for Health, and Mölnlycke Health Care.

Kapp S, Gerdtz M, Miller C, et al. The clinical and cost effectiveness of remote expert wound nurse consultation for healing of pressure injuries among residential aged care patients: A protocol for a prospective pilot parallel cluster randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2023;20(8):2953‐2963. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14121

Endnotes

1 Fitzpatrick T. The validity and practicality of sun‐reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(6):869‐871.

2 European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guidelines. The International Guideline. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA; 2019.

3 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Chronic Cutaneous Ulcer and Burn Wounds—Developing Products for Treatment; 2006. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory‐information/search‐fda‐guidance‐documents/chronic‐cutaneous‐ulcer‐and‐burn‐wounds‐developing‐products‐treatment

4 Hahnel E, Lichterfeld A, Blume‐Peytavi U, Kottner J. The epidemiology of skin conditions in the aged: a systematic review. J Tissue Viability. 2017;26(1):20‐28.

5 International Wound Journal (Ed). News and Views. Editorial. Mölnlycke partners with Tissue Analytics to simplify and standardise chronic wound care. Int Wound J. 2018;15(2):185‐187.

6 Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373‐383.

7 Sonnad S, Goldsack J, Mohr P, Tunis S. Methodological recommendations for comparative research on the treatment of chronic wounds. J Wound Care. 2013;22(9):470‐480.

8 Driver V, Gould L, Dotson P, et al. Identification and content validation of wound therapy clinical endpoints relevant to clinical practice and patient values for FDA approval. Part 1. Survey of the wound care community. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25:454‐465.

9 Driver V, Gould L, Dotson P, Allen L, Carter M, Bolton L. Evidence supporting wound care end points relevant to clinical practice and patients’ lives. Part 2. Literature survey. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27:80‐89.

10 Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, Price P. Outcomes in controlled and comparative studies on non‐healing wounds: recommendations to improve the quality of evidence in wound management. J Wound Care. 2010;19(6):239‐268.

11 Liu Z, Saldanha I, Margolis D, Dumville J, Cullum N. Outcomes in Cochrane systematic reviews related to wound care: an investigation into prespecification. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25:292‐305.

12 Miranda J, Deonizio A, Abbade J, Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Abbade L. Quality of reporting of outcomes in trials of therapeutic interventions for pressure injuries in adults: a systematic methodological survey. Int Wound J. 2020;18:147‐157.

13 Waterlow J. A risk assessment card. Nurs Times. 1985;81:24‐27.

14 Kantor J, Margolis D. Efficacy and prognostic value of simple wound measurements. Arch Dermatol. 2006;134:1571‐1574.

15 Jørgensen L, Sørensen J, Jemec G, Yderstræde K. Methods to assess area and volume of wounds – a systematic review. Int Wound J. 2015;13(4):540‐553.

16 Santamaria N, Ogce F, Gorelik A. Healing rate calculation in the diabetic foot ulcer: comparing different methods. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:786‐789.

17 van Rijswijk L. Measuring wounds to improve outcomes. Am J Nurs. 2013;113(8):60‐61.

18 Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Safety and Quality Improvement Guide Standard 8: Preventing and Managing Pressure Injuries. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2012.

19 Schubert V, Zander M. Analysis of the measurement of four wound variables in elderly patients with pressure ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 1996;9(4):29‐36

20 Sperring B, Baker R. Ten top tips for taking high‐quality digital images of wounds. Wounds Int. 2014;9(2):62‐64.

21 Gorin D, Cordts P, LaMorte W, Menzodian J. The influence of wound geometry on the measurement of wound healing rates in clinical trials. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23(3):524‐528.

22 Gilman T. Wound outcomes: the utility of surface measures. Int J Lower Extrem Wounds. 2004;1(3):125‐132.

23 Jessup R. What is the best method for assessing the rate of wound healing? A comparison of 3 mathematical formulas. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;19(3):138‐146.

24 Tallman P, Muscare E, Carson P, Eaglstein W, Falanga V. Initial rate of healing predicts complete healing of venous ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(10):1231‐1234.

25 Topman G, Sharabani Y, Gefen A. A standardized objective method for continuously measuring the kinematics of cultures covering a mechanically‐damaged site. Med Eng Phys. 2012;34(2):225‐232.

26 Cukjati D, Rebersek S, Miklavcic D. A reliable method of determining wound healing rate. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2001;39(2):263‐271.

27 International Wound Infection Institute (IWII). Wound Infection in Clinical Practice. Wounds International; 2022.

28 Laschinger H, McGillis L, Pedersen C, Almost H. A psychometric analysis of the patient satisfaction with nursing care quality questionnaire: an actionable approach to measuring patient satisfaction. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(3):220‐230.

29 EuroQoL Group. EuroQoL – a new facility for the measurement of health‐related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199‐208.

30 Wilson L, Kapp S, Santamaria L. The direct cost of pressure injuries in an Australian residential aged care setting. Int Wound J. 2018;16(1):64‐70.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data is available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Falanga V, Rivkah Isseroff R, Soulika A, et al. Chronic wounds. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2022;8:50 (1–51). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gefen ABD, Cuddigan J, Haesler E, Kottner J. Our contemporary understanding of the aetiology of pressure ulcers/pressure injuries. Int Wound J. 2022;19(3):692‐704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance . Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: Clinical Practice Guidelines. The International Guideline. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hahnel E, Lichterfeld A, Blume‐Peytavi U, Kottner J. The epidemiology of skin conditions in the aged: a systematic review. J Tissue Viability. 2017;26(1):20‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australian Government. AIoHaW . Residential Aged Care Quality Indicators—January to March 2022. 2022; https://www.gen‐agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/2021‐22‐Quality‐Indicators/RACS‐QI‐report‐January‐to‐March‐2022‐previous‐releases.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nghiema S, Campbell J, Walker R, Byrnes J, Chaboyer W. Pressure injuries in Australian public hospitals: a cost of illness study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;130:1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Padula W, Delarmente B. The national cost of hospital‐acquired pressure injuries in the United States. Int Wound J. 2019;16(3):634‐640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guest J, Fuller G, Vowden P. Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK's National Health Service in 2017/2018: update from 2012/2013. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e045253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Australian Commision on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Safety and Quality Improvement Guide Standard 8: Preventing and Managing Pressure Injuries. 2012. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Australian Government Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety . Final Report: Care, Dignity and Respect 2021; https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final‐report. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Australian Government . Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Intermim Report “Neglect”—Extract from Interim Report. 2019; Retrieved November 26, 2019: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/news/Pages/media-releases/interim-report-released-31-october-2019.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee D, Chow Choi K, Chan C, et al. The impact on patient health and service outcomes of introducing nurse consultants: a historically matched controlled study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(431):1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kapp S. Successful implementation of clinical practice guidelines for pressure risk management in a home nursing setting. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;5:895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Santamaria N, Carville K, Ellis I, Prentice J. The effectiveness of digital imaging and remote expert wound consultation on healing rates in chronic lower leg ulcers in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Prim Int J Austral Wound Manag Assoc. 2004;12(2):62‐72. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goh L, Zhu X. Effectiveness of telemedicine for distant wound care advice to‐ wards patient outcomes: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int Arch Nurs Health Care. 2017;3(2):1‐9. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frick K. Microcosting quantity data collection methods. Med Care. 2009;47(7):S76‐S81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilson L, Kapp S, Santamaria N. The direct cost of pressure injuries in an Australian residential aged care setting. Int Wound J. 2019;16(1):64‐70. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Padula W, Gibbons R, Valuck R, et al. Are evidence‐based practices associated with effective prevention of hospital‐acquired pressure ulcers in US academic medical centers? Med Care. 2016;54(5):512‐518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Padula W, Pronovost P, Makic M, et al. Value of hospital resources for effective pressure injury prevention: a cost‐effectiveness analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(2):132‐141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eldridge S, Lancaster G, Campbell M, et al. Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klaic M, Kapp S, Hudson P, et al. Implementability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a conceptual framework. Implement Sci. 2022;17(10):4‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whitehead A, Sully B, Campbell M. Pilot and feasibility studies: is there a difference from each other and from a randomised controlled trial? Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(1):130‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eldridge S, Chan C, Campbell M, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoffmann T, Glasziou P, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;34:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eldridge S, Costelloe C, Kahan B, Lancaster G, Kerry S. How big should the pilot study for my cluster randomised trial be? Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(3):1039‐1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. EuroQol . EQ‐5D‐5L User Guide: Basic Information on How to Use the EQ5D‐5L Instrument. 2022. https://www.euroqol.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/EQ-5D-5L_UserGuide_2015.pdf. 2015.

- 27. Norman R, Cronin P, Viney R. A pilot discrete choice experiment to explore preferences for EQ‐5D‐5L health states. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(3):287‐298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Padula W, Lee K, Pronovost P. Using Economic Evaluation to Illustrate Value of Care for Improving Patient Safety and Quality: Choosing the Right Method. Journal of Patient Safety. 2017;00(00):1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weinstein MC, Torrance G, McGuire A. 2009. QALYs: the basics. Value in health. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30. Padula B, Chen Y, Santamaria N. Five‐layer border dressings as part of a quality improvement bundle to prevent pressure injuries in US skilled nursing facilities and Australian nursing homes: A cost‐effectiveness analysis. Int Wound J. 2019;16(6):1263‐1272. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford university press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.