Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive malignant brain tumor and has a high mortality rate. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has emerged as a promising approach for the treatment of malignant brain tumors. However, the use of PDT for the treatment of GBM has been limited by its low blood‒brain barrier (BBB) permeability and lack of cancer-targeting ability. Herein, brain endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles (bEVs) were used as a biocompatible nanoplatform to transport photosensitizers into brain tumors across the BBB. To enhance PDT efficacy, the photosensitizer chlorin e6 (Ce6) was linked to mitochondria-targeting triphenylphosphonium (TPP) and entrapped into bEVs. TPP-conjugated Ce6 (TPP-Ce6) selectively accumulated in the mitochondria, which rendered brain tumor cells more susceptible to reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis under light irradiation. Moreover, the encapsulation of TPP-Ce6 into bEVs markedly improved the aqueous stability and cellular internalization of TPP-Ce6, leading to significantly enhanced PDT efficacy in U87MG GBM cells. An in vivo biodistribution study using orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice showed that bEVs containing TPP-Ce6 [bEV(TPP-Ce6)] substantially accumulated in brain tumors after BBB penetration via transferrin receptor-mediated transcytosis. As such, bEV(TPP-Ce6)-mediated PDT considerably inhibited the growth of GBM without causing adverse systemic toxicity, suggesting that mitochondria are an effective target for photodynamic GBM therapy.

Key words: Extracellular vesicle, Chlorin e6, Triphenylphosphonium, Mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer, Photodynamic therapy, Blood‒brain barrier, Glioblastoma, Transferrin receptor

Graphical abstract

Brain endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles are used as biocompatible nanoplatforms to transport mitochondria-targeting photosensitizers into glioblastoma across the blood‒brain barrier. Under light irradiation, the mitochondria-targeting photosensitizers trigger the apoptosis of glioblastoma.

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive malignant brain tumor and has a low survival rate and poor prognosis1, 2, 3. Patients with GBM have a median survival time of less than 1 year, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 4%4,5. Despite advances in the multimodal treatment of surgical resections with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy in the clinic, the effectiveness of this treatment remains limited owing to the inherent resistance of glioma cells to chemo- and radiotherapy along with poor transport of therapeutics to target brain tumors6.

Recently, clinical trials of photodynamic therapy (PDT) have shown great promise for the eradication of malignant brain tumors7, 8, 9. PDT, wherein photosensitizers generate cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) under light, can selectively kill infiltrating malignant brain tumors with minimal damage to nearby healthy tissues because light can be precisely focused on a specific tumor region10, 11, 12. Despite the selective tumor destruction of PDT, the therapeutic efficacy of PDT for brain tumors has been limited by poor penetration of photosensitizers through the protective blood‒brain barrier (BBB).

With the remarkable recent advances in nanocarrier-based drug delivery, a variety of nanocarriers with surface decoration of BBB-targeting ligands have been developed to penetrate the BBB via receptor-mediated endocytosis13 and transcytosis14. Moreover, nanoparticles can considerably improve the pharmacokinetics and tumor-targeting efficacy of encapsulated drugs. However, despite the promise of nanocarrier-based drug delivery, its translation to clinical settings remains a challenge, mainly due to the inherent toxicity of nanocarriers, particularly artificial ones15,16. Moreover, surface modifications of nanocarriers with BBB-targeting ligands are often found to be complicated and require laborious engineering processes17. Therefore, the development of highly biocompatible nanocarriers capable of efficient BBB penetration is indispensable to facilitate the translation of nanocarrier-based brain tumor therapy to clinical use.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), cell-derived nanoscale vesicles for intercellular communication, have recently emerged as natural nanocarriers for drug delivery18,19. Due to their endogenous origin, they possess exceptional biocompatibility, a prolonged half-life in blood circulation, and no or minimal immunogenicity18,19. Moreover, EVs are effective endogenous nanocarriers that can cross the BBB via receptor-mediated endocytosis20,21. The significance of EVs as endogenous nanocarriers is that they express tissue-specific surface proteins derived from parental cells22,23. Therefore, it is hypothesized that EVs derived from brain endothelial cells would display brain endothelial-specific proteins for efficient transport of therapeutic agents across the BBB via interaction with brain endothelial cells.

In recent years, subcellular organelle-targeted delivery of therapeutics has shown great promise to enhance therapeutic efficacy with minimized side effects. Mitochondria are vital subcellular organelles in eukaryotic cells, and they regulate cellular functions because they are energy powerhouses of the cells. Mitochondria are also decisive regulators of apoptosis24. Because mitochondrial damage triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis, targeting mitochondria has been recognized as an effective strategy for cancer treatment25,26. In particular, mitochondria are highly susceptible to oxidative damage induced by excessive ROS generation27. Thus, mitochondria-targeted PDT has emerged as a promising strategy for efficient cancer treatment26. Many efforts have been made to develop nanocarriers incorporated with mitochondria-targeting moieties for the targeted delivery of photosensitizers to the mitochondria of cancer cells28. However, mitochondria-targeted nanocarriers do not guarantee high mitochondrial accumulation of photosensitizers due to the premature leakage of photosensitizers prior to reaching the target mitochondria, which inevitably leads to limited efficacy in PDT. Recently, the use of mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer integrated with nanocarriers has proven to be effective for mitochondria-targeted PDT29.

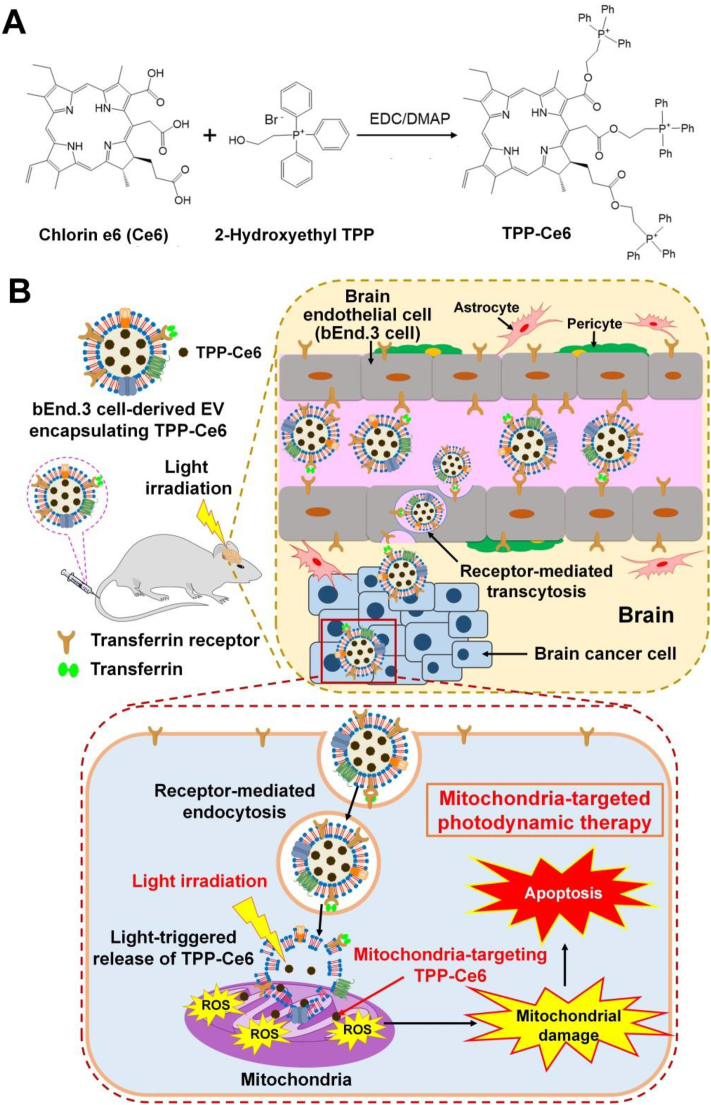

Inspired by the potential of brain endothelial cell-derived EVs for efficient BBB penetration, we propose brain endothelial cell-derived EV-based PDT for the safe and effective treatment of brain tumors. In this study, to achieve efficient PDT via high mitochondrial localization of photosensitizers, we synthesized a mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer by incorporating triphenylphosphonium (TPP), a positively charged lipophilic mitochondria-targeting agent30, to chlorin e6 (Ce6) via an ester linkage (Fig. 1A). Naturally occurring brain endothelial bEnd.3 cell-derived EVs (bEVs) were used to encapsulate the mitochondria-targeting TPP-conjugated Ce6 (TPP-Ce6). The brain endothelial cell-derived EVs would allow efficient encapsulation of TPP-Ce6 and cross the BBB effectively with exceptional biocompatibility. A bEV containing TPP-Ce6 [bEV–(TPP-Ce6)] could effectively disrupt mitochondria of GBM cells under light irradiation, leading to the efficient treatment of GBM. Additionally, compared to other synthetic nanocarrier-based PDT, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) fully addresses safety and toxicity concerns.

Figure 1.

(A) Synthetic scheme of TPP-Ce6. (B) Schematic illustration of the mitochondria-targeted PDT using bEV–(TPP-Ce6) that crosses the BBB. After bEV–(TPP-Ce6) is intravenously injected into orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice, it penetrates the blood‒brain barrier through transferrin receptor-mediated transcytosis, followed by the internalization into U87MG brain cancer cells. After endocytosis, TPP-Ce6 is efficiently released from bEV–(TPP-Ce6) upon irradiation with 660-nm light. The released TPP-Ce6 preferentially accumulates within mitochondria and generates ROS upon light irradiation. The ROS induce mitochondrial damage and apoptotic cell death.

Fig. 1B shows a schematic of the PDT using a bEV encapsulating mitochondria-targeting TPP-Ce6. After bEV–(TPP-Ce6) is administered to brain tumor-bearing mice, it penetrates the BBB through receptor-mediated transcytosis, followed by internalization into brain tumor cells through endocytosis. Light treatment stimulates the EV to release TPP-Ce6. The resulting TPP-Ce6 efficiently accumulates within mitochondria and produce ROS upon exposure to light. The ROS induce mitochondrial disruption and apoptosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of using bEVs as a BBB-crossing natural nanoplatform for mitochondria-targeted GBM PDT. The BBB penetration mechanism of bEVs was also elucidated in this study. This biocompatible bEV-based mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer has significant promise for the clinical translation of GBM treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of bEVs and TPP-Ce6-loaded bEVs

bEnd.3 cells were cultured in DMEM with EV-free fetal bovine serum (FBS) (ThermoFisher Scientific) to produce EVs. bEnd.3 cell-cultured media were centrifuged for 15 min at 1500 g to remove cell debris. ExoQuick-TC™ (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, USA) was used to isolate bEVs. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA, Nanosight NS300, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) was used to determine the concentration of bEVs. TPP-Ce6 was synthesized as previously reported31. The detailed synthesis is described in Supporting Information. To produce TPP-Ce6-loaded EVs, stock solutions of TPP-Ce6 (20 mg/mL) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were prepared. The TPP-Ce6 solution in DMSO (10 μL, 0.2 mg/mL) was mixed with 5 × 1011 bEVs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.5 mL). The DMSO concentration in the PBS was adjusted to 4% (v/v). The solution was subjected to agitation for 2 h. Subsequently, the mixture was purified from free TPP-Ce6 using desalting columns (Cytiva, Marlborough, USA), resulting in bEV–(TPP-Ce6). bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were stored at 4 °C for further use. Successful loading of TPP-Ce6 into the bEVs was confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopy. The absorbance of TPP-Ce6 at 664 nm was measured to determine the encapsulation efficiency (EE) of TPP-Ce6 in bEVs, which is defined as Eq. (1):

| (1) |

The hydrodynamic sizes and surface charges of EV-derived samples were determined using NTA (Nanosight NS300) and Zetasizer (Nano-ZS, Malvern), respectively. Morphologies of blank bEVs and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Talos F200X, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

2.2. In vitro transcytosis of TPP-Ce6-loaded EVs using a transwell BBB model

The in vitro BBB model composed of bEnd.3 and U87MG cells was constructed to assess the BBB permeability and glioma uptake of bEV–(TPP-Ce6). bEnd.3 and U87MG cells were cultured in 10% FBS-containing DMEM. The simulated BBB double-layer was prepared by culturing bEnd.3 cells on Transwell filter inserts (0.4-μm pore size, Corning-Costar Corp., Corning, USA) and U87MG cells in the lower compartment. Briefly, bEnd.3 cells in 400 μL of culture media were seeded on the Transwell filter inserts (5 × 106 cells/well). U87MG cells in 800 μL of culture media were inoculated in the lower chamber (5 × 106 cells/well). The culture media were replaced every two days, and the integrity and permeability of the cell layers were assessed by the measurement of trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) using an EVOM2 epithelial voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, USA). The multilayered bEnd.3 cells were cultured until their TEER values reach 200 Ω cm2 at least. After the culture medium in the upper chamber was removed, TPP-Ce6 or bEV–(TPP-Ce6) (10 μmol/L TPP-Ce6) in DMEM was added into the compartment and incubated for 4 h. To quantify the transcytosis of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) across the BBB layers, the amount of TPP-Ce6 in the lower chamber was quantified by the measurement of its fluorescence using a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax® iD3). To quantify the uptake of Ce6 and TPP-Ce6 samples by U87MG cells in the stimulated BBB model, U87MG cells cultured in the lower compartment were collected at 4 h post-incubation with the samples (10 μmol/L of TPP-Ce6 and Ce6). The amount of Ce6 or TPP-Ce6 in the cells was analyzed using a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) of samples were determined using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where A is membrane area (0.33 cm2); t is incubation time (4 h); Vreceiver is volume of receiver (lower compartment, cm3); Creceiver is concentration of receiver (lower compartment, μg/mL); Cdonor intitial is initial concentration of donor (upper compartment, μg/mL).

To quantify the bEVs penetrating the simulated BBB layers, fluorescently labeled bEVs were used to encapsulate TPP-Ce6. Rhodamine B (RB)-labeled bEVs (RB-bEVs) were prepared by mixing 1 × 1012 bEVs with RB isothiocyanate (0.4 μg) in 0.5 mL PBS. The solution was stirred at 4 °C for 2 h in the dark. It was subjected to PD G-25 columns to remove free RB isothiocyanate. RB-bEVs or RB-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) (10 μmol/L TPP-Ce6) in DMEM were added into the upper compartment as described earlier. After 4 h of incubation, the amounts of RB-bEV and RB-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) that crossed the simulated BBB were determined by the measurement of fluorescence intensity of RB in the cells cultured in each compartment. Papp values of the samples were also calculated based on the aforementioned formula.

2.3. Mechanism of transferrin receptor-mediated transcytosis of bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

To examine the mechanism behind the transcytosis of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) across the BBB, hDFB, U87MG, and bEnd.3 cells were inoculated in 12-well plate (3 × 105 cells/well). After 24 h of incubation, the cells were washed by PBS. Subsequently, the cells were pretreated with transferrin (apo-transferrin from mouse, Sigma–Aldrich) at various concentrations. After 30 min of treatment, the cells were rinsed with PBS, followed by incubation with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) for 4 h. The cells without pre-treatment with transferrin were also incubated with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) as a control. After the cells were detached by trypsin, their fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX).

2.4. In vitro phototoxicity evaluation

To assess the photodynamic effects of TPP-Ce6-bearing EVs, the viability of U87MG cells after various treatments in the presence or absence of laser irradiation was measured using a standard MTT assay32. Ce6 and TPP-Ce6 samples at an equivalent Ce6 (or TPP-Ce6) concentration (10 μmol/L, 5.38 × 1010 bEVs/mL) were added to U87MG cells. Cytotoxicity of blank bEVs against U87 cells was also assessed at various concentrations of bEVs. After 4 h of treatments, the cells were exposed to a 660 nm light for 1 min. The cells without light irradiation were adopted as a negative control. Cell viability was measured after 24 h of incubation.

2.5. Preparation of orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Gachon University (Approval number: LCDI-2017-0131). Orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice were prepared using U87MG cells stably expressing luciferase (U87MG-luc) according to a previous method33. Briefly, male athymic mice of 5 weeks of age (20–30 g) were placed on a stereotactic device (Harvard Apparatus, USA) under inhalation anesthesia using 1%–1.5% isoflurane. U87MG-luc cells (1 × 105 cells) suspended in 2 μL of PBS were injected into the right striatum at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min through a small hole on the skull at a position 2.0 mm lateral, 0.2 mm anterior, and 3.2 mm ventral to the bregma. The formation of brain tumors in the mice was identified by bioluminescence intensity (BLI).

2.6. In vivo brain tumor uptake study of bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

To visualize the brain tumor uptake of bEVs by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled bEVs were prepared to encapsulate TPP-Ce6. FITC (0.4 μg) was added to 500 μL PBS-containing 1 × 1012 bEVs and kept at 4 °C for 2 h in the dark. The final product was purified using desalting columns. The FITC-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) of 100 μL was intravenously injected into the orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice through the tail vein (0.8 μmol/kg for TPP-Ce6). After 2 h, the GBM-bearing mice were transcardially perfused with 10 mmol/L potassium PBS followed by 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution. Brains were collected, divided into 4 mm coronal slices, and post-fixed with 4% (v/v) PFA solution at 4 °C overnight. The brain coronal sections (40 μm thickness) were obtained using a vibratome (Leica V1000S, Germany) and placed on coverslips. The sections were stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and then scanned by CLSM. The fluorescence intensity in the images was quantitatively analyzed using Nikon NIS-E image software.

2.7. In vivo biodistribution study and brain-tumor accumulation of bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

To evaluate in vivo real-time biodistribution of bEV–(TPP-Ce6), Ce6, and TPP-Ce6, orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice (n = 4) received the intravenous (i.v.) injection of each sample (100 μL, 1.71 μmol/kg for TPP-Ce6). Whole-body fluorescence images were acquired at the predetermined time intervals within 24 h after i.v. injection using in vivo imaging systems (IVIS) with a long wavelength emission filter (640–720 nm) (Ami HT imaging system, Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, AZ, USA). Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity in the images was carried out using the region of interest (ROI) function of imaging software (Aura Imaging 2.20, Spectral Instruments Imaging). The ROI of the brain tumor was manually selected based on its bioluminescence.

2.8. In vivo photodynamic therapy of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) for the treatment of GBM

The orthotopic GBM-bearing mice were divided into five groups (n = 4) and intravenously injected with one of the following samples: (i) PBS, (ii) PBS + L (L indicates light irradiation), (iii) Ce6 (1.71 μmol/kg) + L, (iv) TPP-Ce6 (1.71 μmol/kg) + L, and (v) bEV–(TPP-Ce6) (1.71 μmol/kg) + L. At 4 h post-injection, the tumor sites of the mice were illuminated with a 660-nm laser (150 mW, 5 min) on the skull. After the injection, the bioluminescence signal from the tumor area in the brain was scanned daily, with subsequent intraperitoneal injection of 150 mg/kg D-luciferin for each imaging session. The images were repeatedly acquired over 10 min at intervals of 2 min using IVIS (Ami HT imaging system). Regions of bioluminescence signal were determined using Aura imaging software (Spectral Instruments Imaging). On the ninth day after treatment with samples and light irradiation, the tumor-included brain and major organs (e.g., heart, liver, lungs, kidneys, and spleen) were collected and fixed in 4% (v/v) para-formaldehyde solution for H&E staining.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All the results were obtained in triplicate unless specified otherwise. All the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were carried out using ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test. ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were considered to be significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Design of mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer-loaded bEVs for safe and efficient in vivo GBM therapy

PDT using photosensitizer-loaded nanocarriers has great promise for the treatment of brain tumors. However, the use of photosensitizer-loaded nanocarriers for PDT of brain tumors has been limited by its low BBB permeability, lack of cancer-targeting ability, and intrinsic toxicity of nanocarriers. Moreover, most of the artificial nanocarriers encounter certain critical obstacles, such as systemic toxicity and poor pharmacokinetics. To overcome these challenges, in this study, a naturally occurring bEV that hijacks the BBB is proposed as a biocompatible nanocarrier to transport photosensitizers into brain tumors efficiently. In addition, we propose the encapsulation of mitochondria-targeting photosensitizers in bEVs to enhance the PDT efficacy for GBM through mitochondrial damage. Therefore, the mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer-loaded bEVs can achieve efficient in vivo GBM therapy owing to their intrinsic BBB-penetration capability and long-term blood circulatory capability.

3.2. Synthesis of TPP-Ce6 and preparation of TPP-Ce6-loaded bEVs

2-Hydroxyethyl TPP was chemically coupled with carboxylic acid groups of Ce6 to obtain mitochondria-targeting TPP-Ce6 photosensitizer (Fig. 1A). The synthesis of TPP- Ce6 was confirmed by 1H NMR (Supporting Information Fig. S1). The conjugation of 2-hydroxyethyl TPP to Ce6 was confirmed by the peaks at 7.7–7.9 ppm (aromatic protons) and 3.7–3.8 ppm (–CH2–CH2– adjacent to phosphorus). Three TPP moieties were coupled to Ce6, as indicated by the integration ratio of the peak for (C6H5)3P+ (7.7–7.9 ppm) to the peak for –CH=CH2 in the Ce6 (8.2 ppm) (Fig. S1).

To prepare TPP-Ce6-loaded EVs with enhanced BBB penetration capability, EVs were isolated from brain endothelial bEnd.3 cells. EVs were simply mixed with TPP-Ce6 solution in PBS containing 4% (v/v) DMSO. Since EVs have a hydrophobic lipid bilayer surrounding a hydrophilic core18, they may contain hydrophilic TPP-Ce6 in the aqueous core or at the bilayer interface. DMSO was adopted to enhance the solubility and loading efficiency of TPP-Ce6 owing to its permeability across lipid membranes. However, the concentration of DMSO in PBS was adjusted to 4% (v/v) because higher concentrations of DMSO induce a significant loss of EVs via membrane disruption34. The amount of TPP-Ce6 loaded into EVs was quantified by ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopic analysis. Fig. 2A represents the UV–Vis absorption spectra of bEV, Ce6, 2-hydroxyethyl TPP, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6). The UV–Vis absorption spectrum of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) illustrated distinct characteristic peaks representing 2-hydroxyethyl TPP (268 nm) and Ce6 (398 and 664 nm) (Fig. 2A). These characteristic peaks from the bEV–(TPP-Ce6) absorption spectrum verified the effective encapsulation of TPP-Ce6 into bEVs. The encapsulation efficiency of TPP-Ce6 in bEV–(TPP-Ce6) was calculated to be 27.9%.

Figure 2.

(A) Absorbance spectra of blank bEVs, Ce6, 2-hydroxyethyl TPP, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) solutions. (B) TEM images of blank bEV and bEV–(TPP-Ce6). Scale bar: 50 nm. (C) Changes in fluorescence intensity of TPP-Ce6 and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) after incubation in PBS for 14 days under normal light conditions (n = 3). (D) TPP-Ce6 release profiles from bEV–(TPP-Ce6) before and after light irradiation (660 nm, 1 min) at different incubation times (n = 3). (E) Schematic diagram of in vitro BBB model using bEnd.3 cells. (F) Apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) of TPP-Ce6 and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) measured using an in vitro BBB model (n = 3). (G) Relative Ce6 uptake of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) by U87MG cells after crossing BBB layers (n = 3). (H) Relative cellular uptake of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in U87MG cells following pre-treatment with Tf at different concentrations (n = 3). (I) Changes in the uptake levels of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) by different cell lines after pre-treatment with Tf (100 μg/mL) (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01).

The hydrodynamic sizes and surface charges of blank bEVs and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were measured via nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and Zetasizer, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the size of blank bEVs was 118.0 ± 7.3 nm and slightly increased to 122.6 ± 7.2 nm after the loading of TPP-Ce6, which can be explained by the incorporation of lipophilic TPP-Ce6 into hydrophobic lipid bilayers of EVs. In addition, all the bEV samples exhibited negative surface charges. TEM results reveal spherical morphologies of blank bEVs and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) (Fig. 2B). The diameters of the blank bEVs and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were 50–80 nm. The nanoscale bEV–(TPP-Ce6) would avoid nonspecific clearance by the reticuloendothelial system and increase blood circulation half-life35.

Table 1.

Sizes and zeta potentials of various EV samples (n = 3).

| Sample | Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| bEVs | 118.0 ± 7.3 | ‒20.4 ± 0.8 |

| bEV–(TPP-Ce6) | 122.6 ± 7.2 | ‒22.0 ± 1.0 |

3.3. High colloidal stability of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) under physiological conditions

The stability of nanoparticles in biologically relevant media plays an important role in determining their bioavailability in vivo36. To demonstrate colloidal stability against serum proteins, the size changes of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were monitored after incubation in PBS containing 10% (v/v) EV-free FBS. bEV–(TPP-Ce6) exhibited no significant size changes for 5 days at 37 °C (Supporting Information Fig. S2). The high colloidal stability of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) against serum proteins, and the nanoscale size of the vesicles should extend the half-life of the substance in blood circulation and improve tumor accumulation.

3.4. Prolonged aqueous stability of TPP-Ce6 by encapsulation into EVs

Ce6, a fluorophore with an excellent molar extinction coefficient at 660 nm, has shown great potential as an effective therapeutic and imaging agent37. However, Ce6 faces several challenges due to its inherent shortcomings, such as poor water solubility, irreversible degradation, and rapid photobleaching38. To demonstrate the prolonged aqueous stability of TPP-Ce6 in bEVs, the fluorescence intensity of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) and free TPP-Ce6 incubated in PBS was monitored. As displayed in Fig. 2C, the fluorescence intensity of TPP-Ce6 was noticeably dropped to 36.8% of its initial value after incubation in PBS for 14 days. However, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) retained more than 71.2% of its initial fluorescence intensity of TPP-Ce6 under the same condition. These findings indicate that bEVs significantly boost the aqueous stability of TPP-Ce6 by shielding it from external destabilizing radicals, as reported in a previous study39.

3.5. Light-triggered release of TPP-Ce6 from bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

To demonstrate the light-responsive drug release of bEV–(TPP-Ce6), it was pretreated with a 660 nm laser for 1 min, followed by incubation in PBS at 37 °C. In the absence of laser treatment, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) released 56.7% of TPP-Ce6 within 24 h (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, after 1 min of laser irradiation, the cumulative release of TPP-Ce6 reached 86.3% 24 h after the incubation. This result suggests that the release of TPP-Ce6 from bEV–(TPP-Ce6) can be accelerated by light irradiation. The light-triggered release of TPP-Ce6 might be attributed to the destabilization of the EV membranes by light-induced ROS generation from TPP-Ce6. It has been reported that ROS generated from photosensitizers induce lipid peroxidation, consequently disrupting EVs40.

3.6. Efficient BBB transcytosis of TPP-Ce6-Loaded bEVs

Penetrating the BBB and delivering therapeutics to brain tumors at therapeutic levels is a significant bottleneck for the successful treatment of brain tumors41. We hypothesized that brain endothelial cell-derived EVs would cross the BBB through receptor-mediated transcytosis because EVs are known to possess cell-specific proteins found in the membrane of the parent cells22,23. To investigate whether bEVs can penetrate the BBB and enter brain tumor cells, an in vitro BBB model using the transwell method was established. The simulated BBB double-layer was prepared by culturing bEnd.3 cells in the upper chamber and U87MG human GBM cells in the lower chamber. The upper and lower chambers were separated by a porous membrane (Fig. 2E). After bEnd.3 cells in the upper chamber reached a confluent monolayer, they were incubated with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) and TPP-Ce6 for 4 h. Then, the amount of TPP-Ce6 released into the lower compartment was quantified. As illustrated in Fig. 2F, the entrapment of TPP-Ce6 in bEVs resulted in a significant increase in transport across the BBB, which was indicated by the increased apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) value. To verify that bEVs cross the BBB, Papp values of RB-labeled blank bEVs and RB-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were measured. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S3, both blank bEVs and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) exhibited high Papp values in BBB penetration, demonstrating the effective BBB transport of bEVs themselves.

To assess the capability of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) to cross the BBB and target brain tumors, cellular uptake levels of TPP-Ce6 and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in lower chambers were quantified. The bEnd.3 cells in upper chambers were treated with bEV–(TPP-Ce6), Ce6, and TPP-Ce6 and incubated for 4 h. The samples that crossed the bEnd.3 layer could be internalized by U87MG cells in the lower chamber. As presented in Fig. 2G, TPP-Ce6 was more efficiently internalized by the U87MG cells than Ce6. Moreover, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) significantly improved the intracellular uptake level of TPP-Ce6 into U87MG cells. This study demonstrates that encapsulating TPP-Ce6 in bEVs greatly enhances its cellular internalization into GBM. The efficient intracellular transport of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) might be attributed to the favorable binding of bEVs with the cell membranes42.

3.7. Transferrin-mediated brain targeting of bEVs

Receptor-mediated transcytosis is one of the main routes for the transport of therapeutics through endothelial cells of the BBB43,44. A variety of therapeutic molecules, including chemical drugs, polymeric nanoparticles, antibodies, and EVs, have adopted this strategy44,45. Transferrin receptor (TfR), which is overexpressed on the surface of glioma and brain endothelial cells45,46, is a widely validated receptor for the BBB penetration of therapeutics through receptor-mediated transcytosis45. Recent studies have reported that blood-derived exosomes express TfR abundantly and exhibit natural BBB-crossing capability through the transferrin-TfR interaction47,48.

Based on the efficient BBB penetration capability of bEV–(TPP-Ce6), we hypothesized that bEVs could cross the BBB through the transferrin-TfR interaction. Indeed, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay verified that bEVs contained high levels of transferrin, which might be bound to TfR expressed on the bEVs (Supporting Information Fig. S4). To demonstrate our hypothesis, transferrin competition binding study, in which bEnd.3 cells were pretreated with free transferrin prior to the incubation with bEV–(TPP-Ce6), was conducted. Upon pre-incubation with free transferrin, the uptake level of bEVs by bEnd.3 cells noticeably decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2H). This indicates that pre-treatment with free transferrin saturated TfR on the bEnd.3 cells, leading to a decrease in the amount of available TfR on the surface of bEnd.3 cells. Consequently, cellular internalization of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) by bEnd.3 cells was significantly reduced. This result reveals that the enhanced internalization of the bEV–(TPP-Ce6) by bEnd.3 cells is associated with TfR-mediated transcytosis. The same Tf competition binding assay was performed using U87MG cells and hDFB human dermal fibroblast cells. When bEnd.3 cells were replaced with hDFB cells, the cellular uptake level of bEVs was also reduced by the pre-treatment of Tf (Fig. 2I). However, it should be noted that the pre-treatment of Tf showed a much more significant influence on the cellular uptake of bEVs by bEnd.3 cells than by hDFB cells. The reduction in the cellular uptake of bEVs by U87MG cells was also more significant than that of bEVs by hDFB cells after Tf pre-treatment. This result provides further evidence for the critical role of the transferrin-TfR interaction in the BBB penetration of bEVs.

Although our study suggests that bEVs could effectively cross the BBB through the transferrin-TfR interaction, elucidating the exact molecular mechanisms still requires further investigation. In addition to TfR, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors and insulin receptors have been demonstrated to facilitate the transcytosis of bEVs across the BBB49. Further studies, such as proteomic analysis of bEVs, are required to understand the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the transcytosis of bEVs across the BBB. Moreover, establishing realistic and dynamic in vitro BBB models could be crucial to investigate molecular interactions between bEVs and brain endothelial cells50.

3.8. Enhanced mitochondrial uptake of Ce6 by conjugation with TPP

Recent studies have revealed that conjugation of TPP to photosensitizers improved their mitochondrial targeting in cells26,51. To demonstrate whether TPP conjugation enhances the mitochondrial targeting of Ce6, mitochondrial accumulation of TPP-Ce6 and Ce6 in U87MG cells were compared. As shown in Fig. 3A, TPP-Ce6 exhibited substantially higher mitochondrial uptake in U87MG cells than Ce6, demonstrating that positively charged TPP has high affinity to mitochondrial membranes. Additionally, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) showed significantly higher mitochondrial uptake than TPP-Ce6 owing to the increased uptake of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) by U87MG cells.

Figure 3.

(A) Relative mitochondrial uptake of various samples in U87MG cells (n = 3). (B) Confocal micrographs displaying intracellular localization of Ce6 and TPP-Ce6 in U87MG cells. U87MG cells were treated with Ce6 or TPP-Ce6 (red) for 2 h, followed by staining with MitoTracker (green) for the visualization of mitochondria. The red fluorescence intensity of the cells and Mander's overlap coefficients were calculated from the images (n = 4). Scale bars: 20 μm. (C) Intracellular localization of rhodamine B (RB)-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in U87MG cells stained with MitoTracker Green. Mander's overlap coefficients indicating the RB-labeled bEVs or TPP-Ce6 signals overlapped with mitochondria staining were determined from the images (n = 4). Scale bars: 25 μm. (D) Relative intracellular ROS levels in U87MG cells treated with various samples before and after light irradiation (660 nm, 1 min) (n = 3). (E) Fluorescence images of U87MG cells generating intracellular ROS after various treatments in the absence or presence of light exposure (660 nm, 1 min). Scale bars: 50 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD (∗∗P < 0.01).

To further verify the mitochondrial targeting of TPP-Ce6 in U87MG cells, we performed CLSM after incubating U87MG cells with Ce6 and TPP-Ce6. We measured Mander's overlap coefficients to quantify the colocalization degree of TPP-Ce6 (or Ce6) in the mitochondria, which were labeled with MitoTracker green. The mean fluorescence intensity of TPP-Ce6-treated U87MG cells was stronger than that of Ce6-treated U87MG cells, indicating that TPP-Ce6 enters the cells more efficiently than Ce6 (Fig. 3B). This result corresponded to the cellular uptake result in Fig. 2G. Red fluorescence, representing Ce6 or TPP-Ce6, overlapped effectively with the green fluorescence of MitoTracker Green. Notably, a quantitative colocalization examination based on Mander's overlap coefficients revealed that TPP-Ce6 was localized in the mitochondria more efficiently than Ce6 (e.g., 0.50 ± 0.02 for TPP-Ce6; 0.31 ± 0.03 for Ce6) (Fig. 3C). This result clearly demonstrates the mitochondria-targeting ability of TPP.

3.9. Cytoplasmic localization of bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

To investigate the intracellular distribution of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in brain tumor cells, RB-labeled bEVs (RB-bEVs) were prepared to load TPP-Ce6. The prepared RB-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) was added to bEnd.3 and U87MG cells. Both bEnd.3 and U87MG cells were labeled with LysoTracker, which preferentially stains endo/lysosomal compartments, to determine whether bEV–(TPP-Ce6) can enter cells via the endocytic pathway. As illustrated in Supporting Information Fig. S5, a significant amount of RB-bEVs (red) were colocalized with LysoTracker (green) in both bEnd.3 and U87MG cells. This result verifies that bEV–(TPP-Ce6) enters cells via endocytosis. Intracellular distributions of RB-bEVs (red dots) and TPP-Ce6 (cyan dots) in U87MG cells after incubation with RB-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) are shown in Fig. 3C. Both RB-bEVs and TPP-Ce6 were distributed primarily in the cytoplasm. Moreover, significant amounts of RB-bEV and TPP-Ce6 were localized in the mitochondria (green) stained with MitoTracker Green. The Mander's overlap coefficient values of mitochondria with TPP-Ce6 were 2 times higher than those with RB-bEVs in U87MG cells (Fig. 3C), indicating that the TPP-Ce6 released from bEVs efficiently accumulated in the mitochondria.

3.10. Light-triggered intracellular ROS generation using TPP-Ce6-loaded bEVs

The efficacy in ROS generation of photosensitizers under light illumination is critical for photodynamic cancer therapy. To investigate whether TPP-Ce6 produces ROS upon 660-nm light irradiation, the relative ROS production from free Ce6 solution, free TPP-Ce6 solution, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) suspensions in a cell-free system was quantified before and after 660-nm laser treatment. The laser irradiation considerably augmented the ROS generation of Ce6 and TPP-Ce6 (Supporting Information Fig. S6). Notably, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) exhibited a superior capability to produce ROS compared to TPP-Ce6 (Fig. S6). This finding can be attributed to the increased stability of TPP-Ce6 in aqueous solutions when encapsulated in bEVs (Fig. 2C). Our findings indicate that bEV–(TPP-Ce6) is an effective photosensitizer for PDT.

Previous studies have reported that conjugation of TPP facilitates the intracellular transport of photosensitizers to mitochondria and thus affects their intracellular ROS generation51,52. To examine whether the conjugation of TPP to Ce6 affects the intracellular ROS generation of Ce6, ROS levels in U87MG cells that received Ce6, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were measured before and after light irradiation. TPP-Ce6 significantly increased the intracellular ROS generation in U87MG cells relative to Ce6, regardless of light irradiation (Fig. 3D). Encapsulating TPP-Ce6 in bEVs considerably increased its ROS generation in U87MG cells. This result can be explained by the enhanced cellular internalization of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) compared to TPP-Ce6. Notably, the intracellular ROS levels in U87MG cells after treatment with bEV–(TPP-Ce6), Ce6, and TPP-Ce6 were significantly increased after 1 min of light exposure (Fig. 3D). This result demonstrated the efficient photodynamic effects of Ce6. Fluorescence images of U87MG cells stained with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate were obtained to observe light-triggered ROS production by TPP-Ce6. As displayed in Fig. 3E, we observed weak fluorescence signals in the cells treated with Ce6. Treatment with TPP-Ce6 or bEV–(TPP-Ce6) increased cellular fluorescence signals. The fluorescence signals in the cells increased significantly when the cells were exposed to a 660-nm laser. The highest fluorescence signals were observed within the cells that received bEV–(TPP-Ce6) and light irradiation (Fig. 3E), indicating the high efficacy of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in ROS generation. This might be ascribed to the efficient uptake of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) by U87MG cells.

3.11. In vitro PDT using mitochondria-targeting TPP-Ce6-loaded bEVs

Mitochondria are key organelles of cellular energy metabolism53. When mitochondria are damaged, they initiate the reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential and cascades for apoptosis54,55. Therefore, mitochondria are potential targets for effective PDT. A conventional JC-1 staining assay was adopted to determine whether mitochondria were destructed by various treatments. In healthy mitochondria, JC-1 dye forms aggregates with red fluorescence. In contrast, in apoptotic cells with lowered mitochondria membrane potential, JC-1 localizes to the cytosol in its monomeric form emitting green fluorescence. Consequently, a reduction in the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio indicated mitochondrial damage. Strong red fluorescence was found in the control group, suggesting a minor change in mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 4A). The red fluorescence in Ce6-or TPP-Ce6-treated cells drastically decreased upon light irradiation. Importantly, red-to-green fluorescence ratio was lowest in cells treated with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) plus laser irradiation (Fig. 4A), indicating the most significant mitochondrial damage. This result demonstrates that mitochondria-targeting PDT by bEV–(TPP-Ce6) effectively damaged the mitochondria.

Figure 4.

(A) Fluorescence images JC-1 stained U87MG cells after various treatments: 1) control, 2) Ce6+L, 3) TPP-Ce6+L, and 4) bEV–(TPP-Ce6)+L. The red JC-1 aggregates indicate mitochondria with normal membrane potentials, and the green JC-1 monomer indicates mitochondria with depolarized membrane potentials. Red/green fluorescence ratios of JC-1 stained U87MG cells after various treatments were obtained from the fluorescence images (n = 5). Scale bars: 50 μm.(B) Viabilities of U87MG cells treated with various samples in the absence or presence of light exposure (660 nm, 1 min) (n = 5). (C) Fluorescence images of co-stained U87MG cells after treatment with Ce6, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6). The cells were co-stained with calcein-AM (live cells, green) and ethidium homodimer-1 (dead cells, red). The cells were irradiated with light (660 nm, 1 min). Scale bars: 100 μm. (D) Viabilities of U87MG cells treated with various concentrations of bEVs (n = 5). (E) Apoptosis staining of U87MG cells treated with various samples. Data are presented as mean ± SD (∗∗P < 0.01).

The viability of U87MG cells after various treatments under laser irradiation was analyzed using a standard MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 4B, more than 92% of the cells retained viability upon 1 min of light irradiation only, suggesting that light irradiation was minimally cytotoxic. The viability of U87MG cells slightly decreased upon incubation with TPP-Ce6 and Ce6. The cytotoxicity of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) was more significant than that of free TPP-Ce6. The increased uptake of TPP-Ce6 by bEVs might have contributed to this increased cytotoxicity. A significant reduction in cell viability was observed when the cells received Ce6 or TPP-Ce6 upon exposure to light. The viabilities of the cells incubated with Ce6 and TPP-Ce6 under light irradiation were 72.5% and 42.2%, respectively (Fig. 4B). The higher phototoxicity of TPP-Ce6 compared to Ce6 might be attributed to the increased mitochondrial damage that leads to apoptosis. Notably high phototoxicity (8.9% cell viability) was observed when bEV–(TPP-Ce6) was added to the cells under light irradiation (Fig. 4B). This is attributed to the efficient cellular uptake and mitochondrial targeting of bEV–(TPP-Ce6). The photodynamic effects of various samples were observed by live/dead staining assay. Fluorescence images of the dye-stained U87MG cells that received various treatments are provided in Fig. 4C. The treatment with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) plus laser irradiation showed the highest percentage of dead cells, which correlated with the cell viability results (Fig. 4B).

The cytotoxicity of the blank bEVs against U87MG cells was assessed to demonstrate their biosafety. The blank bEVs exhibited very minimal cytotoxicity up to a concentration of 1.0 × 1011 bEVs/mL (>90% viability) (Fig. 4D). The bEV and TPP-Ce6 concentrations tested for the in vitro cytotoxicity study (Fig. 4B) were approximately 5.38 × 1010 bEVs/mL and 10 μmol/L, respectively. The innate toxicity of drug carriers remains a major challenge to their clinical use. Therefore, the extremely low toxicity of bEVs suggests that bEV-based photosensitizers have great promise to facilitate the clinical translation of brain tumor-targeted PDT.

To investigate whether phototoxicity of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) results from apoptosis, apoptosis rates of U87MG cells treated with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were analyzed before and after 660 nm light irradiation (Fig. 4E). Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/PI staining assay revealed that bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated U87MG cells showed a higher level of total apoptosis than those treated with TPP-Ce6, regardless of laser exposure. The number of total apoptotic cells dramatically increased when the cells received TPP-Ce6 under light irradiation. Treatment with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) combined with light illumination substantially increased the percentage of total apoptotic (early and late apoptosis) cells from 28.14 to 66.80%. The apoptosis results corresponded well to the cytotoxicity results (Fig. 4B). In conjunction with the intracellular ROS analysis (Fig. 3D), the apoptosis results reveal that elevated oxidative stress caused by the photodynamic effects of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) triggers the apoptosis of GBM cells.

3.12. Effective brain tumor accumulation of bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

Biodistribution and brain tumor accumulation of various samples were evaluated using luciferase-expressing U87MG GBM-xenografted mice. The samples were intravenously administered to the orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice via the tail vein. The distribution of Ce6, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in the body was analyzed by measuring the fluorescence from Ce6 and TPP-Ce6 using IVIS. Within 10 min after i.v. injection, the fluorescence signals of Ce6, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were detected across the whole body—that is, the fluorescence signal of circulating bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in the blood (Fig. 5A). While weak fluorescence appeared in the brains of mice treated with Ce6 or TPP-Ce6 at 24 h post-injection, the bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated mice showed high fluorescence intensity in the brain at 24 h after injection (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) In vivo real-time fluorescence imaging of orthotopic GBM-xenografted mouse model after i.v. administration of free Ce6, free TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6). Luminescence imaging of mice before injection with samples was also conducted to determine the location of brain tumors. (B) Time course ratios of the fluorescence intensity in the whole brain at each time point to the whole body at 1 min for free Ce6-, free TPP-Ce6-, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated mice (n = 4), determined by IVIS. (C) Time course ratios of the fluorescence intensity in the brain tumor to the whole brain for free Ce6-, free TPP-Ce6-, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated mice (n = 4), determined by IVIS fluorescence imaging. (D) Ex vivo imaging of tumor-contained brain and major organs at 24 h post-injection of various samples. (E) Quantitation of fluorescence signal from ex vivo imaging of tumor-contained brain and major organs at 24 h-post i.v. administration of various samples (n = 4). (F) Confocal micrographs showing the distribution of FITC-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in the brain and brain tumors of mice after i.v. Injection. The boundary between tumor regions and surrounding normal tissue was indicated by a white dotted line. Scale bars: 100 μm. (G) Quantitation of mean fluorescence intensities from FITC-bEV and TPP-Ce6 accumulated in tumor regions and surrounding normal tissues in the brains of mice after i.v. injection with FITC-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) (n = 4). Data are presented as mean ± SD (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01).

The time course ratios of the fluorescence intensity in whole brain to whole body at 1 min post-injection were also measured to quantitatively estimate the brain-selective localization of bEV–(TPP-Ce6), Ce6, and TPP-Ce6. The time courses of whole brain-to-whole body fluorescence ratios for Ce6-and TPP-Ce6-treated mice were similar (Fig. 5B). In contrast, bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated mice exhibited higher whole brain-to-whole body fluorescence ratios than Ce6-and TPP-Ce6-treated mice. These results suggest that bEV–(TPP-Ce6) could effectively transport TPP-Ce6 into the brain across the BBB. To assess the GBM-targeting capability of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in mice, time course brain tumor-to-whole brain fluorescence ratios were measured after i.v. injection of bEV–(TPP-Ce6). As shown in Fig. 5C, bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated mice displayed higher brain tumor-to-whole brain fluorescence ratios over time compared to Ce6-and TPP-Ce6-treated mice. These results demonstrate that bEVs can significantly enhance the accumulation of TPP-Ce6 in brain tissue and brain tumors. It should be noted that the brain tumor-to-whole brain fluorescence ratio was found to be highest at 4 h post-injection of bEV–(TPP-Ce6). Therefore, the mice were irradiated with light 4 h after the administration of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) to achieve the most effective PDT using bEV–(TPP-Ce6).

Ex vivo imaging of the GBM-bearing brains and major organs collected 24 h after injection was performed. All the mice showed the highest level of fluorescence signal in the liver at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 5D). Notably, at 24 h post-administration, the level of TPP-Ce6 localization in the brain of the bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-injected mice was markedly higher than that for TPP-Ce6-injected mice (Fig. 5E), which corresponded to the real-time biodistribution result (Fig. 5A).

In situ localization of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) in brain tumors of mice after i.v. Injection was evaluated using CLSM. To observe the brain tumor accumulation of bEV–(TPP-Ce6), FITC was used to label bEVs. bEV–(TPP-Ce6) labeled with FITC was intravenously injected into orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice. Brain tissue was collected 2 h after the injection, and localization of FITC-labeled bEV–(TPP-Ce6) around the boundary between normal and tumor tissue in brain slices was assessed using CLSM. As shown in Fig. 5F and G, green fluorescence [FITC-labeled bEV–(FITC-bEV)] and red fluorescence (TPP-Ce6) were much stronger at the tumor site than at the normal site. This result indicates that bEV–(TPP-Ce6) accumulates preferentially in brain tumor tissue.

3.13. Efficient in vivo PDT effects of bEV–(TPP-Ce6)

The in vivo PDT effects of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were evaluated using luciferase-expressing U87MG-bearing mice. The representative images of BLI in brain tumors of the mice injected with various samples were displayed in Fig. 6A. The mice were illuminated with a 660 nm laser (5 min) 4 h after i.v. injection of each sample. The BLI in the brain tumors treated with PBS increased dramatically for 9 days, regardless of light irradiation (Fig. 6A). Free Ce6- and TPP-Ce6-treated mice showed the limited suppression of tumor growth upon laser treatment. In contrast, treatment with bEV–(TPP-Ce6) plus laser irradiation showed the most significant suppression of tumor growth (Fig. 6A and B). Safety has been a major concern for the use of synthetic nanocarriers for PDT. Notably, all the samples caused negligible body weight changes during 9 days, indicating that none of the samples induced any adverse effects (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) Time-lapse BLI in the brain tumors of orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice after i.v. administration with PBS, free Ce6, free TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) upon light irradiation (660 nm, 5 min). The mice were irradiated with 660 nm light for 5 min at 4 h post-i.v. injection of each sample. (B) Changes in the BLI of brain tumors of mice after treatment with various samples and light irradiation compared to that on Day 0 (n = 4). Data are presented as mean ± SD (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01). (C) Changes in the body weights of GBM-xenografted mice (n = 4) for 9 days after i.v. injection of various samples and light irradiation (n.s.; not significant). (D) H&E stained brain sections of mice on Day 9 after i.v. injection of PBS, Ce6, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) combined with light irradiation. The tumor region of interest in the brain section (as indicated by black boxes) was magnified. Scale bars of the magnified images indicate 100 μm. (E) H&E staining of major organs of the mice on Day 9 after i.v. Injection of various samples and light irradiation. Scale bars: 100 μm.

The efficient PDT effects of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) were also confirmed by H&E staining of brain sections from GBM-xenografted mice. As displayed in Fig. 6D, the brain tumor tissue of the mice injected with PBS exhibited highly dense tumor cells, regardless of light irradiation. In contrast, low cell density and nuclear shrinkage were observed in the tumor tissue of mice injected with free Ce6, TPP-Ce6, and bEV–(TPP-Ce6) upon exposure to light. The smallest tumor size and largest area of necrotic change and nuclear shrinkage in tumor tissue were observed in bEV–(TPP-Ce6)-treated mice subjected to light irradiation, indicating the high PDT efficacy of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) for the treatment of GBM (Fig. 6D). Negligible pathological changes were observed in the major organs of mice in all groups, indicating the high biosafety of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) for PDT (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that bEV–(TPP-Ce6) combined with light irradiation can efficiently inhibit the growth of GBM without adverse effects.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a mitochondria-targeting photosensitizer, TPP-Ce6, was synthesized and encapsulated into brain endothelial cell-derived EVs for the safe and effective treatment of GBM. TPP-Ce6 effectively accumulated in the mitochondria of U87MG human GBM cells and showed higher PDT efficacy than Ce6. Importantly, bEVs significantly boosted the aqueous stability and cellular internalization of TPP-Ce6, leading to an increase in intracellular ROS production under laser irradiation. Therefore, bEV–(TPP-Ce6) showed significantly enhanced PDT performance in U87MG cells. An in vivo biodistribution study using orthotopic GBM-xenografted mice showed that bEV–(TPP-Ce6) effectively targeted brain tumors after efficient BBB penetration. As a result, administration of bEV–(TPP-Ce6) combined with light irradiation efficiently suppressed tumor growth in GBM-xenografted mice without causing adverse systemic toxicity. This study offers new insights into the use of biocompatible bEVs for safe and efficient photodynamic GBM therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) [(NRF-2022R1A2C1007207, Korea), Basic Research Laboratory Program (NRF-2020R1A4A2002894, Korea), Basic Science Research Program (NRF-2020R1A2B5B01001719, Korea), and Engineering Research Center of Excellence Program (NRF-2016R-1A5A1010148, Korea)]. This work was also supported by Basic Science Research Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1I1A1A01042149, Korea). YSZ acknowledges support by the Brigham Research Institute, USA.

Author contributions

Thuy Giang Nguyen Cao conceptualized the project, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the original manuscript. Ji Hee Kang performed experiments and wrote the original manuscript. Su Jin Kang performed experiments and wrote the original manuscript. Quan Truong Hoang performed experiments. Han Chang Kang provided resources for experiments. Won Jong Rhee provided funding and supervised the project. Yu Shrike Zhang performed data analysis and revised the manuscript. Young Tag Ko provided funding and supervised the project. Min Suk Shim supervised the project, provided funding, and revised the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.03.023.

Contributor Information

Won Jong Rhee, Email: wjrhee@inu.ac.kr.

Yu Shrike Zhang, Email: yszhang@research.bwh.harvard.edu.

Young Tag Ko, Email: youngtakko@gachon.ac.kr.

Min Suk Shim, Email: msshim@inu.ac.kr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Stupp R., et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsons D.W., et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walid M.S. Prognostic factors for long-term survival after glioblastoma. Perm J. 2008;12:45–48. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakkar J.P., et al. Epidemiologic and molecular prognostic review of glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1985–1996. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrom Q.T., et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006‒2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:1–56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tığlı Aydın R.S., Kaynak G., Gümüşderelioğlu M. Salinomycin encapsulated nanoparticles as a targeting vehicle for glioblastoma cells. J Biomed Mater. 2016;104:455–464. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupont C., et al. INtraoperative photodynamic therapy for glioblastomas (INDYGO): study protocol for a phase I clinical trial. Clin Neurosurg. 2019;84:414–419. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akimoto J. Photodynamic therapy for malignant brain tumors. Neurol Med -Chir. 2016;56(4):151–157. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2015-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmoudi K., et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for the treatment of high-grade gliomas. J Neuro Oncol. 2019;141:595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolmans D.E., Fukumura D., Jain R.K. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller P.J., Wilson B.C. Photodynamic therapy of brain tumors—a work in progress. Laser Surg Med. 2006;38:384–389. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer S.W., Chen C.C. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. Front Surg. 2019;6:81. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2019.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu D.Z., et al. The enhancement of siPLK1 penetration across BBB and its anti glioblastoma activity in vivo by magnet and transferrin co-modified nanoparticle. Nanomedicine. 2018;14:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zensi A., et al. Albumin nanoparticles targeted with Apo E enter the CNS by transcytosis and are delivered to neurones. J Control Release. 2009;137:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenblum D., Joshi N., Tao W., Karp J.M., Peer D. Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1410. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03705-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sukhanova A., Bozrova S., Sokolov P., Berestovoy M., Karaulov A., Nabiev I. Dependence of nanoparticle toxicity on their physical and chemical properties. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2018;13:44. doi: 10.1186/s11671-018-2457-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao H. Progress and perspectives on targeting nanoparticles for brain drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:268–286. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha D., Yang N., Nadithe V. Exosomes as therapeutic drug carriers and delivery vehicles across biological membranes: current perspectives and future challenges. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang Y., Duan L., Lu J., Xia J. Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery. Theranostics. 2021;11:3183–3195. doi: 10.7150/thno.52570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shan S., et al. Functionalized macrophage exosomes with panobinostat and PPM1D-siRNA for diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas therapy. Adv Sci. 2022;9 doi: 10.1002/advs.202200353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saint-Pol J., Gosselet F., Duban-Deweer S., Pottiez G., Karamanos Y. Targeting and crossing the blood‒brain barrier with extracellular vesicles. Cells. 2020;9:851. doi: 10.3390/cells9040851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle L.M., Wang M.Z. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells. 2019;8:727. doi: 10.3390/cells8070727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y., Liu Y., Liu H., Tang W.H. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberg S.E., Chandel N.S. Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:9–15. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green D.R., Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakrabortty S., et al. Mitochondria targeted protein-ruthenium photosensitizer for efficient photodynamic applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2512–2519. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J., Shamul J.G., Kwizera E.A., He X. Recent advancements in mitochondria-targeted nanoparticle drug delivery for cancer therapy. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:743. doi: 10.3390/nano12050743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Battogtokh G., Ko Y.T. Mitochondrial-targeted photosensitizer-loaded folate-albumin nanoparticle for photodynamic therapy of cancer. Nanomedicine. 2017;13:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho D.Y., et al. Triphenylphosphonium-conjugated poly(ε-caprolactone)-based self-assembled nanostructures as nanosized drugs and drug delivery carriers for mitochondria-targeting synergistic anticancer drug delivery. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:5479–5491. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen Cao T.G., et al. Mitochondria-targeting sonosensitizer-loaded extracellular vesicles for chemo-sonodynamic therapy. J Control Release. 2023;354:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truong Hoang Q., Lee D., Choi D.G., Kim Y.C., Shim M.S. Efficient and selective cancer therapy using pro-oxidant drug-loaded reactive oxygen species (ROS)-responsive polypeptide micelles. J Ind Eng Chem. 2021;95:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang J.H., Ko Y.T. Dual-selective photodynamic therapy with a mitochondria-targeted photosensitizer and fiber optic cannula for malignant brain tumors. Biomater Sci. 2019;7:2812–2825. doi: 10.1039/c9bm00403c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen Cao T.G., et al. Safe and targeted sonodynamic cancer therapy using biocompatible exosome-based nanosonosensitizers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:25575–25588. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c22883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoshyar N., Gray S., Han H., Bao G. The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine. 2016;11:673–692. doi: 10.2217/nnm.16.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abstiens K., Maslanka Figueroa S., Gregoritza M., Goepferich A.M. Interaction of functionalized nanoparticles with serum proteins and its impact on colloidal stability and cargo leaching. Soft Matter. 2019;15:709–720. doi: 10.1039/c8sm02189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilson R.C., Tang R., Gautam K.S., Grabowska D., Achilefu S. Trafficking of a single photosensitizing molecule to different intracellular organelles demonstrates effective hydroxyl radical-mediated photodynamic therapy in the endoplasmic reticulum. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019;30:1451–1458. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hongying Y., Fuyuan W., Zhiyi Z. Photobleaching of chlorins in homogeneous and heterogeneous media. Dyes Pigments. 1999;43:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Son J., et al. Gelatin-chlorin e6 conjugate for in vivo photodynamic therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2019;17:50. doi: 10.1186/s12951-019-0475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacellar I.O.L., Baptista M.S. Mechanisms of photosensitized lipid oxidation and membrane permeabilization. ACS Omega. 2019;4:21636–21646. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b03244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lockman P.R., et al. Heterogeneous blood–tumor barrier permeability determines drug efficacy in experimental brain metastases of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5664–5678. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prada I., Meldolesi J. Binding and fusion of extracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane of their cell targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1296. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terstappen G.C., Meyer A.H., Bell R.D., Zhang W. Strategies for delivering therapeutics across the blood‒brain barrier. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:362–383. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00139-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pulgar V.M. Transcytosis to cross the blood brain barrier, new advancements and challenges. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:1019. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi H., et al. Strategies for targeted delivery of exosomes to the brain: advantages and challenges. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:672. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14030672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calzolari A., et al. Transferrin receptor 2 is frequently and highly expressed in glioblastomas. Transl Oncol. 2010;3:123–134. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu M., et al. Dopamine-loaded blood exosomes targeted to brain for better treatment of Parkinson's disease. J Control Release. 2018;287:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qi H., et al. Blood exosomes endowed with magnetic and targeting properties for cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3323–3333. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haqqani A.S., Delaney C.E., Tremblay T.-L., Sodja C., Sandhu J.K., Stanimirovic D.B. Method for isolation and molecular characterization of extracellular microvesicles released from brain endothelial cells. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10:4. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramos-Zaldívar H.M., et al. Extracellular vesicles through the blood–brain barrier: a review. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022;19:60. doi: 10.1186/s12987-022-00359-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noh I., et al. Enhanced photodynamic cancer treatment by mitochondria-targeting and brominated near-infrared fluorophores. Adv Sci. 2018;5 doi: 10.1002/advs.201700481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang C.J., et al. Image-guided combination chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy using a mitochondria-targeted molecular probe with aggregation-induced emission characteristics. Chem Sci. 2015;6:4580–4586. doi: 10.1039/c5sc00826c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X., Fang P., Mai J., Choi E.T., Wang H., Yang X. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species as novel therapy for inflammatory diseases and cancers. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghosh P., Vidal C., Dey S., Zhang L. Mitochondria targeting as an effective strategy for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3363. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei G., Wang Y., Huang X., Yang G., Zhao J., Zhou S. Induction of mitochondrial apoptosis for cancer therapy via dual-targeted cascade-responsive multifunctional micelles. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6:8137–8147. doi: 10.1039/c8tb02159g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.