Abstract

Diabetes foot ulcer (DFU) is one of the most intractable complications of diabetes and is related to a number of risk factors. DFU therapy is difficult and involves long‐term interdisciplinary collaboration, causing patients physical and emotional pain and increasing medical costs. With a rising number of diabetes patients, it is vital to figure out the causes and treatment techniques of DFU in a precise and complete manner, which will assist alleviate patients' suffering and decrease excessive medical expenditure. Here, we summarised the characteristics and progress of the physical therapy methods for the DFU, emphasised the important role of appropriate exercise and nutritional supplementation in the treatment of DFU, and discussed the application prospects of non‐traditional physical therapy such as electrical stimulation (ES), and photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) in the treatment of DFU based on clinical experimental records in ClinicalTrials.gov.

Keywords: diabetes foot ulcer, electrical stimulation, medical expenses, photobiomodulation therapy, physical therapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a metabolic condition characterised by hyperglycemia and brought on by a number of different factors. It is among the most prevalent chronic illnesses in the twenty‐first century. 1 According to the 10th edition of the Global Diabetes Map published by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) in December 2021, the prevalence of diabetes increases with age, peaking in the 75‐ to 79‐year‐old age group (24.0%). Diabetes were frequently referred to as a ‘diseases of affluence’ because of its higher prevalence in urban regions (12.1%) compared to rural areas (8.3%) and high‐income countries (11.1%) compared to low‐income countries (5.5%). Advanced and effective blood glucose control has greatly improved patient survival, but it has also paradoxically led to an increase in diabetes prevalence and global medical expenditure on diabetes. Diabetes‐related medical expenses were expected to reach 1054 billion dollars by 2045, with 783 million diabetic patients worldwide. 2

As a chronic metabolic disease, diabetes can only be controlled but cannot be cured. Long‐term poor blood glucose control may lead to complications with high disability and mortality rates, such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and renal failure, which not only raises medical costs but also endangers patients' lives. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Among all the complications, diabetes foot ulcer (DFU) is one of the most common consequences of diabetes, affecting up to 30% of diabetic people. Every 20 s, one DFU patient worldwide suffers an amputation due to worsening foot ulcer symptoms, and severe DFU can lead to death. 8 DFU also has one of the highest global disease burdens. 9 Fortunately, DFU is relatively easy to detect and prevent, 10 and the treatment outcome of early DFU has good benefits.

Therefore, given the increasing number of diabetic patients and medical burden, it is imperative to understand the mechanism of DFU formation and to improve the existing clinical strategies for the treatment of DFU, so as to improve the poor prognosis and reduce the cost of DFU. 11

At present, the treatment methods for DFU include wound dressings, autologous stem cell transplantation, acellular dermal matrix coverage, growth factor supplementation, and physical therapy. 12 In addition, nanocarriers, genetic engineering, and 3D printing‐based approaches to DFU are being developed and applied clinically. 13 Compared with pharmacotherapy, physical therapy has obvious advantages in simplicity, cost, and adverse effects, so it has been an important choice for clinical DFU treatment. This review started with diabetes symptoms and then analysed the causes of the unhealing diabetic wounds. We regarded reasonable exercise and meeting the nutritional needs of patients as the treatment of DFU, and more comprehensively established the characteristics and breakthrough progress of physical therapy, especially energy‐based physical therapies for DFU.

2. REFRACTORY FACTORS OF DFU HEALING

2.1. Individual factors

Long‐term hyperglycemia in diabetes produces a series of factors that are not conducive to skin regeneration and wound healing, such as biomechanical abnormalities caused by peripheral neuropathy, dry skin, and dysregulation of capillary temperature, making DFU difficult to cure. 14 Meanwhile, hyperalgesia caused by peripheral neuropathy can make the patient's skin painless after breakage, and prevent timely care and treatment, which lead to prolonged irritation, infection, and inflammation in the wound healing process. Age is a crucial component in wound healing, and the aging of skin cells and the decline of immune system function make DFU more common in the elderly. 15 Because of impaired glucose cell conversion and storage in diabetic patients, their utilisation of glucose is reduced, which leads to increased food intake. While patients consuming too much food, the intake of lipids is also increased, resulting in elevated levels of free fatty acids (FFA) in the blood, excess fat deposition, and further increased blood viscosity and slower blood flow. At the same time, the affinity of glycosylated haemoglobin for oxygen increases, and the release of oxygen slows down, so that the wound tissue is in a state of hypoxia for a long time, which will also aggravate DFU. 16 In addition, poor family economic conditions, lack of awareness of the dangers of diabetic complications, and lack of standardised life care are all potential factors in the formation of DFU.

2.2. Chronic impairment

Repeated stimulation and infection can cause long‐term oxidative stress in the wound. Inflammatory cells and pathogens consume more oxygen and nutrients. Neutrophils over‐recruit in the wound, after phagocytosis of bacteria, generating a significant number of proteases and oxygen free radicals, causing damage to the skin tissue, making collagen dissolution surpass deposition, resulting in delayed wound healing. At the same time, the combined effects of endotoxin, exotoxin, proteolytic enzymes, and oxygen free radicals cause the biological effects of cytokines and free radical damage, resulting in wound tissue edema and haemorrhage, increase purulent secretions and proteolysis, slow growth and filling of granulation tissue or excessive proliferation, which severely decreases epithelial formation and slows wound healing. In addition, under the hypoxic environment, the antibacterial ability of the wound is greatly reduced. The bacteria can secrete adhesive matrix to coat themselves, adhere to the surface of the wound tissue in the form of bacteria groups, and form a biofilm, which is not only difficult to eliminate, but also hinders the penetration of drugs.

2.3. Adverse microenvironment

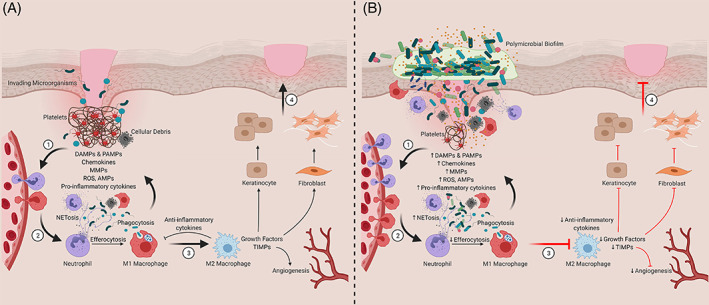

In the high glucose environment, the activity of antioxidant enzymes in skin cells is reduced and the production of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) is increased, resulting in long‐term hypoxia of the wound under oxidative stress. Increased and prolonged inflammation prevents macrophages from switching from pro‐inflammatory to anti‐inflammatory phenotypes, limiting macrophages' role in wound proliferation and remodelling. 17 Meanwhile, persistent inflammation interferes with insulin‐related signalling pathways, aggravates insulin resistance, inhibits insulin's anti‐inflammatory and metabolism‐regulating abilities, and further inhibits diabetic chronic wound healing. High glucose environment also inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of fibroblasts, impairs the function of fibroblasts to secrete TGF‐β, and reduces collagen synthesis. Most importantly, the high glucose environment interferes with the complex crosstalk between immune cells, dermal cells, and epidermal cells, inhibits the immune system's antibacterial ability, inhibits the skin's barrier function and self‐repair ability, and thus delays wound healing (Figure 1). 16 , 18

FIGURE 1.

Contribution of innate immune cells and inflammation to timely and delayed wound healing. (A) Representation of the four phases of wound healing ([1] Haemostasis, [2] Inflammation, [3] Proliferation and [4] Tissue Remodelling). (B) Chronic wounds are stalled in the inflammatory stage. DAMPs, damage‐associate molecular patterns; PAMPs, pathogen‐associated molecular patterns; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; ROS, reactive oxygen species; AMPs, antimicrobial peptides; TIMPs, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases. Created with BioRender.com.Copyright 2021 Versey, da Cruz Nizer, Russell, Zigic, DeZeeuw, Marek, Overhage and Cassol.

Insufficient oxygen supply and nutrient deficiency due to ischemia and ischemia are the main factors contributing to the difficulty of diabetic wound healing, and vascular damage is the most common clinical symptom in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. 19 In general, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), also known as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), is expressed via endothelial‐type nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) to promote vascular growth and permeability, thereby ensuring the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the wound site. In the case of hyperglycemia, high levels of glucose and AGEs consume NO and inhibit the activity of eNOS. The synthesis of NO is reduced, making the growth factor unable to operate, which leads to the vascular damage difficult to repair.

3. PHYSICAL THERAPY OF DFU

The treatment of the chronic wound microenvironment has received attention as the understanding of the healing process has gradually deepened, which has benefited the development of physical therapy. There are two types of physiotherapy for the treatment of DFU, one is the intervention of daily life to improve the quality of life of patients and reduce the possibility of chronic wounds by reducing unreasonable pressure on the patient's foot, increasing exercise or improving nutrition (Table 1). The other category is the direct treatment of wounds to improve the microenvironment of wounds and accelerate wound healing through debridement, negative pressure wound therapy (NPTW), oxygen therapy, and energy‐based physical therapy (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Intervention in daily life for the treatment of DFU.

| Treatment | Name of clinic trials | Intervention/treatment | Estimated enrollment | Starting and ending date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offloading device | Wound Healing: Total Contact Cast versus Custom‐Made Temporary Footwear for Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulceration |

Cast Shoe |

43 | 2001.8 ~ 2005.4 |

| Instant Total Contact Cast to Heal Diabetic Foot Ulcers (ITCC) |

Total contact cast ITCC RCW |

225 | 2010.10 ~ 2012.10 | |

| Sealed Therapeutic Shoe as Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers |

Sealed therapeutic shoe Total contact cast |

150 | August 2, 2019 ~ 2027.12 | |

| A Clinical Investigation Evaluating Wound Closure With OptiPulse™ Versus SOC in the Treatment of Non‐Healing DFU's |

OptiPulse Standard of care off‐loading device |

100 | December 15, 2021 ~ March 15, 2023 | |

| Wheeling to Healing: A Novel Method for Improving Healing of Diabetic Foot Ulceration |

Wheeled Knee Walker Usual and customary care |

68 | May 1, 2022 ~ September 30, 2023 | |

| Celliant Socks to Increase Tissue Oxygenation and Complete Wound Closure in Diabetic Foot Wounds |

Celliant diabetic medical socks control (placebo) medical socks |

254 | July 7, 2022 ~ 2024.8 | |

| Exercise | Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Shorter Treatment Period Using Custom Felt Relief? |

‘Custom felt relief’ Standard relief treatment |

74 | October 1, 2019 ~ June 1, 2023 |

| The Effect of Exercise on Wound Healing While Off‐loading | Exercise | 15 | May 14, 2021 ~ 2023.5 | |

| Exercise Enhances Wound Healing in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers | Structured exercise program | 60 | October 10, 2021 ~ May 31, 2023 | |

| Exercise Therapy for People With a Diabetic Foot Ulcer‐a Feasibility Study | Exercise therapy | 15 | September 1, 2021 ~ October 1, 2022 | |

| Investigation of the Effects of Different Exercise on Wound Healing in Patients with Diabetic Foot Wounds |

Standard treatment Aerobic exercise Exercise protocol |

60 | July 1, 2022 ~ February 1, 2023 | |

| Nutrition supplementation | The Effects of Nutrition Supplementation and Education on the Healing of Diabetic Foot Ulcer (DFU) | Glucose control nutritional shake, nutrition education | 29 | May 23, 2017 ~ May 9, 2018 |

| Nutritional Supplement on Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot | Dietary supplement: abound | 70 | October 1, 2018 ~ May 15, 2020 | |

| Evaluation of Personalised Nutritional Intervention on Wound Healing of Cutaneous Ulcers in Diabetics | Personalised nutritional intervention | 30 | March 1, 2022 ~ December 31, 2024 | |

| Evaluation of a Medical Food for Chronic Wounds |

Medical food Drink mix calorically similar to experimental product |

271 | 2008.6 ~ 2010.12 | |

| Effect of Supplementation With HMB and Glutamine in Wound Healing on Bloody Areas |

Glutamine supplementation HMB |

30 | June 1, 2021 ~ December 31, 2021 | |

| Nutritional Regulation of Wound Inflammation: Part III (FPP3) |

Placebo FPP |

22 | 2014.12 ~ February 10, 2018 |

Note: OptiPulse is supplied as a pair of footwear. One side is fitted with an off loader and shin pumping unit, and the other acts as pressure reducing footwear.

Abbreviations: FPP, Fermented Papaya Preparation; HMB, β‐Hydroxy‐β‐Methylbutyrate; ITCC, Instant Total Contact Cast; RCW, Removable Cast Walker.

TABLE 2.

Treatments of improving wound microenvironment of DFU.

| Treatment | Name of clinic trials | Intervention/treatment | Estimated enrollment | Starting and ending date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debridement | Maggot debridement therapy versus conventional dressing therapy to treat diabetic foot ulcers (MDTDF) |

Maggot debridement therapy Conventional dressing therapy |

138 | 2016.6 ~ 2017.2 |

| Ultrasound assisted wound debridement (UAW) versus standard wound treatment in complicated diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) |

Ultrasound group Surgical group |

51 | November 1, 2017 ~ December 31, 2019 | |

| Real world evidence with the debritom+ TM novel micro water jet technology at a single wound center (EVIDENT) |

Study device debridement SOC debridement |

180 | November 29, 2021 ~ 2023.12 | |

| Negative pressure wound therapy | Trial of vacuum assisted closure therapy in amputation wounds of the diabetic foot | Device: V.A.C. system | 146 | 2002.5 ~ 2005.10 |

| Randomised, controlled multicenter trial of vacuum assisted closure therapy in diabetic foot ulcers |

Moist wound therapy VAC therapy |

335 | 2002.5 ~ 2008.3 | |

| Negative pressure wound therapy registry (NPWTR) | NPWT | 50 000 | 2005.1 ~ 2020.1 | |

| Evaluating the ease of use of a VAC GranuFoam bridge dressing on diabetic foot ulcers receiving VAC negative pressure wound therapy | V.A.C. negative pressure wound therapy system | 33 | 2009.2 ~ 2009.9 | |

| SNaP wound care system versus traditional NPWT device for treatment of chronic wounds |

Traditional NPWT system SNaP wound care system |

132 | 2009.7 ~ 2011.3 | |

| Evaluation of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of DFUs Incl. post amputation wounds | NPWT system | 16 | 2010.1 ~ 2010.7 | |

| Treatment study of negative pressure wound therapy for diabetic foot wounds (DiaFu) |

Negative pressure wound therapy Standard wound therapy |

360 | 2011.11 ~ 2015.4 | |

| Negative pressure wound therapy as a drug delivery system |

Cardinal Pro +simultaneous irrigation (NPWTi) Cardinal Pro (NPWT) therapy |

150 | June 2, 2015 ~ August 1, 2020 | |

| Single‐use negative pressure wound therapy system versus traditional negative pressure wound therapy system (tNPWT) (NPWT) |

PICO system tNPWT system |

164 | July 2, 2015 ~ November 14, 2017 | |

| Evaluating clinical acceptance of a NPWT wound care system | Invia motion endure | 10 | October 16, 2018 ~ January 30, 2020 | |

| Negative pressure wound therapy in the management of diabetic foot ulcers | Negative pressure wound therapy | 40 | 2019.11 ~ 2021.1 | |

| Cryopreserved versus lyopreserved stravix as an adjunct to NPWT in the treatment of complex wounds |

NPWT and lyopreserved stravix NPWT and cryopreserved stravix |

40 | May 1, 2019 ~ July 1, 2021 | |

| Negative pressure wound therapy in diabetic wounds |

Negative pressure wound therapy delivered through VAC Standard of Care |

80 | May 1, 2019 ~ July 1, 2021 | |

| A dual‐center study evaluating clinical acceptance of a NPWT wound care system | Invia motion endure NPWT system | 25 | December 10, 2020 ~ May 18, 2021 | |

| Mean healing time of wound after vacuum assisted closure (VAC) versus conventional dressing in diabetic foot ulcer patients | Vacuum assisted closure conventional dressing | 60 | February 28, 2020 ~ August 27, 2022 | |

| The study of wound dressings for portable NPWT (NPWT) | Filler dressing of NPWT | 57 | 2011.2 ~ 2016.3 | |

| Oxygen therapy | Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for chronic diabetic lower limb ulcers (HBOT) |

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy Procedure Placebo hyperbaric oxygen chamber |

107 | 2008.4 ~ 2013.4 |

| A prospective, randomised, double‐blind multicenter study comparing continuous diffusion of oxygen (CDO) therapy to standard moist wound therapy (MWT) in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers |

CDO electrochemical tissue oxygenation system Moist wound therapy |

146 | 2012.4 ~ 2016.11 | |

| Efficacy, safety and economic benefits of topical wound oxygen therapy in the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers (TWO2DFU) |

TWO2 device Placebo device |

73 | 2014.10 ~ December 15, 2018 | |

| Can topical oxygen therapy (Natrox™) improve wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers? | Natrox oxygen delivery system (ODS) | 20 | 2015.12 ~ 2016.12 | |

| An observational clinical trial examining the effect of topical oxygen therapy (NATROX) on the rates of healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers | NATROX topical oxygen therapy system | 20 | August 17, 2018 ~ May 31, 2021 | |

| The effect of natrox oxygen wound therapy on the healing rate of chronic diabetic foot ulcers | Natrox oxygen wound therapy | 145 | June 4, 2019 ~ October 18, 2020 | |

| Topical oxygen therapy for diabetic wounds | Topical oxygen chamber for extremities | 40 | February 1, 2020 ~ January 1, 2024 | |

| Effectiveness of vaporous hyperoxia therapy (VHT) in the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers (VHTDFU2) | Vaporous hyperoxia therapy | 30 | October 4, 2021 ~ October 3, 2022 | |

| Energy‐based physical therapies | Effect of natrox oxygen wound therapy on non‐healing wounds and implication of remote monitoring and telehealth for management in the home. | Natrox topical oxygen therapy | 12 | February 12, 2021 ~ November 27, 2022 |

| Effects of high voltage pulsed current (HVPC) and low level laser therapy (LLLT) on wound healing in diabetic ulcers |

High voltage pulsed current Low level laser Standard nursing care |

28 | 2004.3 ~ 2006.12 | |

| Open Multi‐center safety & efficacy study of low‐frequency magnetic fields to treat unresponsive diabetic foot ulcers. |

Forearm tissue exposure with ELF‐MF Thorax tissue exposure with ELF‐MF |

27 | 2006.12 ~ 2014.1 | |

| Monochromatic phototherapy on diabetic foot ulcers |

Monochromatic phototherapy, biolight Monochromatic phototherapy |

107 | 2008.8 ~ 2012.4 | |

| Low level laser therapy and expression of VEGF, NO, VEGFR‐2, HIF‐1α in diabetic foot ulcers |

Low Level Laser(Ga‐As) Placebo |

27 | 2013.6 ~ 2015.2 | |

| Pilot study on auricular vagus nerve stimulation effects in chronic diabetic wounds | PrimeStim | 24 | 2014.2 ~ April 13, 2015 | |

| Wound healing process in diabetic neuropathy and diabetic neuroischemia | Electrical stimulation device | 60 | 2015.4 ~ 2016.4 | |

| Efficacy of laser debridement on pain and bacterial load in chronic wounds |

Er:YAG laser debridement Scalpel/Curette debridement |

22 | January 5, 2017 ~ March 17, 2017 | |

| Study assessing safety and efficacy of B‐cure laser treating diabetic chronic wounds |

Standard hoem treatment LLLT‐808 B‐cure laser machine |

December 16, 2011 ~ March 22, 2013 | ||

| Iontophoresis of treprostinil to enhance wound healing in diabetic foot skin ulcers (InTREPiD) |

Treprostinil iontophoresis Remodulin placebo iontophoresis |

60 | January 28, 2020 ~ 2023.9 |

Abbreviations: CDO, Continuous Diffusion of Oxygen; ELF‐MF, Extremely Low‐Frequency Magnetic Fields; Er:YAG, Erbium:Yttrium‐Aluminium‐Garnet; LLLT, Low Level Laser Therapy; NPWT, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy; NPWTi, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy with Instillation; ODS, Oxygen Delivery System; PICO, Single‐Use Negative Pressure Wound Therapy; SOC, Standard of Care; TWO2, Topical Wound Oxygen Therapy; VAC, Vacuum Assisted Closure.

3.1. Lifestyle interventions

3.1.1. Offloading devices

Due to peripheral neuropathy, the skin perception ability of DFU patients is reduced, and their feet are repeatedly pressed, their blood flow is blocked without consciousness, which directly leads to the aggravation of the disease. Reducing foot pressure is the most direct method in DFU physiotherapy, usually called ‘offloading’, and has the greatest therapeutic effect in areas with high vertical or shear stress. 20 Bed rest, wheelchair, crutch‐assisted gait, total‐contact casts (TCC), removable cast walker (RCW), and offloading shoes are all common methods. 21

TCC is regarded as the gold standard for treating neuropathic foot ulcers and lowering plantar pressure, 20 , 22 , 23 but it is not frequently used in clinic. 24 Because the device is non‐removable, it can force treatment and reduce unnecessary movement of patients, which greatly reduces patient compliance. Ironically, the reason for the decline in patient compliance is precisely the fundamental reason why TCC is superior to other ‘offloading’ methods. 20 TCC has a high medical cost, and its application requires a large amount of time and material costs, which requires medical staff to master the skills of installing TCC. The use of TCC is absolutely prohibited in patients with infection or severe ischemia. TCC is also prohibited in very elderly patients with visual or balance disorders, contralateral foot ulcers or varicose veins. 25 Therefore, in 2002, Armstrong et al. proposed an alternative to TCC: non‐removable RCW, which uses single layer of glass fibre tape to make it impossible for patients to remove the device and called it ‘instant total‐contact cast’ (I‐TCC). 26 , 27 They believed that I‐TCC would completely change the future management of plantar nerve ulcers due to its benefits such as being inexpensive, quick, simple to perform, and has few side effects. 20 However, as mentioned above, the detachable nature of RCW greatly reduces the time for patients to use the pressure offloading devices, resulting in no advantage compared with TCC. 28 According to studies, the average time for DFU patients who insist on using RCW is only one‐third of the prescribed treatment time. 23

The high cost of casts, gait changes due to volume and weight of cast, and decreased comfort caused by increased differences in limb length all lead to a significant reduction in patient compliance. 29 This makes clinicians have to find a more acceptable method for patients: shoes modify. Offloading shoes is the most common treatment in DFU offloading therapy. Compared with casts, patients are more likely to accept minor modifications to their familiar shoes, 30 and offloading shoes can indeed achieve ideal therapeutic effect. 14 , 28 , 31 However, shoes modify cannot completely reverse the impact of offloading shoes on patients' dynamic balance. There are very few studies on dynamic balance combined with offloading shoes. Diabetic patients urgently need to be liberated from this risk and fear of falling. 32

In addition to the common offloading methods described above, there was low‐quality evidence that the use of felt foam can enhance DFU healing and reduce plantar pressure, but further evidence is needed to demonstrate the effectiveness and rationality of these methods in clinical use. 33 , 34

3.1.2. Appropriate exercise

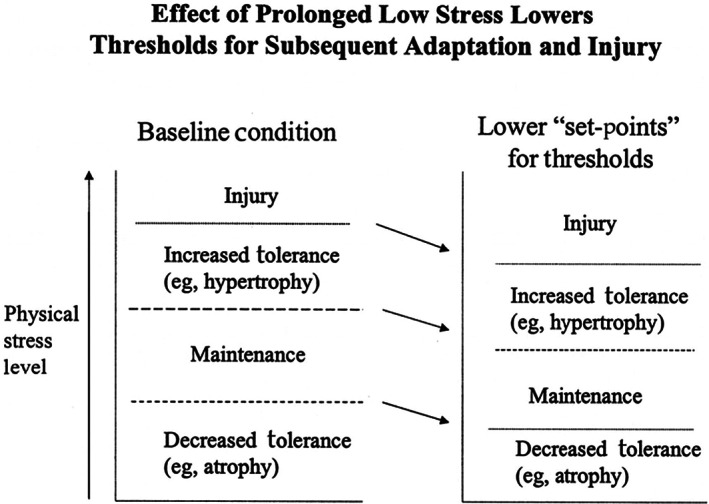

Patients with DFU tend to have a conservative or even deformed gait due to foot ulcers, limited foot movement, and reduced control of body dynamic balance, as evidenced by reduced walking speed and rhythm, shortened stride lengths, and increased variability in stride length. 35 , 36 Traditional medical and rehabilitation approaches emphasised the importance of protecting the insensitive and vulnerable foot as well as reducing foot pressure by reducing unnecessary action. 37 However, there was mounting evidence showing that this view is false, 38 and long‐term low‐frequency foot activity decreases the tolerance of the plantar skin to pressure, causing the foot to be more susceptible to ulceration when activity frequency and pressure are suddenly increased, the theory first proposed by Mueller and Maluf and accepted by the medical practitioners (Figure 2). 39 There was substantial clinical evidence that walking at an appropriate frequency and intensity (at least five times a week for half an hour) not only does not increase the risk of DFU but also significantly improves the quality of patient survival. 40 , 41 Kanade et al. demonstrated that aerobic exercise or walking could improve physical health and glycemic control in DFU patients. 42 At the same time, patients' dynamic balance could be improved further through targeted intervention in their gait. 36 , 43 Mueller made the following recommendations to people at high risk of recurrence of foot ulcers: continue to keep the foot ‘offloading’ after wound healing to reduce stress and protect the foot; gradually increase activity levels to avoid stress on the plantar skin due to excessive step changes. Patients are encouraged to take care of themselves and have their feet checked promptly. 37 Recently, a 16‐week tap dance training program had been shown to significantly improve ankle mobility, lower extremity functional strength, and static postural stability, but this approach was not suitable for patients with severe foot or joint deformities and weakness. 44

FIGURE 2.

Effect of prolonged low stress lowers thresholds for subsequent adaptation and injury. Copyright 2002, Oxford University Press.

3.1.3. Nutrition supplementation

Poor dietary habits are also considered as an important factor in the current diabetes epidemic. 38 Patients with diabetes generally have a high body mass index, but their intake of energy, protein, and essential micronutrients involved in wound healing are surprisingly lower than the minimum recommended by National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and the Dietary Reference Intake. 45 This problem is more severe in the elderly population, as the physiological and nervous systems decline, reducing the elderly sense of smell, taste, and appetite and inhibiting their desire to obtain food; injured pain, reduced mobility, economic constraints, and depression all lead to reduced food intake in the elderly. When elderly patients have wounds, they tend to exhibit malnutrition symptoms. With the aggravation of malnutrition, their immune function is further damaged, the risk of infection is further increased, the speed of wound healing is further slowed, and eventually death. 46 As a result, it is critical to provide nutrition education to patients and to supplement nutrition as needed. 47 Protein supplements, vitamin supplements, mineral supplements, probiotic supplements, and fatty acid supplements are all commonly used nutritional supplements. 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 However, there was only very low‐quality evidence to show the effectiveness of nutritional intervention in the treatment of DFU, and more large‐scale, high‐quality, comprehensive studies are required to clarify the impact of nutritional intervention on DFU in order to help healthcare managers make the best decisions for the patients. 52

3.2. Improving wound microenvironment

3.2.1. Debridement

Surgery is a common treatment for DFU. Debridements, correction of deformities, wound closures, partial amputations are the most common methods. 53 , 54 Debridement is the first step in the treatment of DFU 55 : its purpose is to remove ischemia, devitalized, gangrene, and necrosis from the infected lesion or its vicinity, expose the surrounding healthy tissue, convert chronic wounds into acute wounds, and reduce the adverse effects of exudate and infection on the wound. 56 , 57 It also assists medical personnel in conducting a comprehensive examination and evaluation of the wound in order to determine whether additional surgical treatment is required, and which surgical procedure will be used. 55 , 58

Wilcox et al. conducted an ultra‐large retrospective cohort study using data collected from 525 wound care centers via a web‐based clinical management system that clearly demonstrated that more frequent debridement (more than once every 2 weeks) improved wound healing. 59 liu et al. proposed a five‐in‐one comprehensive treatment approach that included 1 medical symptom treatment, 2 early and thorough debridement, 3 vascular reconstruction, 4 NPWT wound bed preparation, and 5 subsequent dressing changes, surgical skin grafting, or flap grafting depending on the wound condition. It provides a multi‐disciplinary cooperation mode for the comprehensive treatment of internal and external medicine of DFU, which had achieved good clinical results. 60

At present, there are two types of clinical debridement methods, one is surgical debridement, which mainly includes scalpel debridement, saline gauze drying debridement, water flow debridement, and ultrasonic debridement, and the other is non‐surgical debridement, which mainly includes autolytic debridement, enzyme debridement, and biological debridement. 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 Dayya et al. classified and summarised the advantages and disadvantages, indications, and contraindications of these methods, so they will not be repeated here. 7

Not all DFUs require debridement. When a diabetic wound does not cause discomfort or is free of foreign bodies and exudates, dry and necrotic wound tissue can be left in place to assist healthcare staff to assess the potential degree of ischemia in the diabetic wound and to provide a foundation for corrective vascular surgery, and there is a probability that the necrotic wound tissue will fall off on its own. 66 Furthermore, the person performing the debridement must have a basic knowledge of pathophysiology and anatomy. Non‐invasive or invasive testing (eg, angiography) must be performed before or after the initial surgical debridement (at least within 24–48 h) to examine wound vascular deficits in patients with DFU. 67

3.2.2. Negative pressure wound therapy

The NPTW system, which was developed in the 1990s in Germany and the United States, has been widely used in the treatment of DFU. NPTW is based on vacuum‐assisted closure (VAC) and vacuum‐sealed drainage techniques. NPTW can reduce tissue edema and promote cell and granulation tissue growth by increasing blood flow to the wound area and eliminating tissue exudates and proinflammatory factors. Although it is appropriate for almost all acute and chronic wounds, it cannot replace surgical debridement, improve blood circulation, or other wound infection treatment measures. 68 There was considerable clinical evidence that NPWT is more effective than standard of care (SOC) for DFU, which effectively promotes granulation tissue production and reduces the risk of secondary amputation, especially major amputation, and has a similar safety profile to SOC. 66 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73

In order to solve the deficiency of NPTW in the treatment of infection, the combination of liquid infusion has become one of the main directions of the development of NPTW, which is called NPTWi. In comparison to the traditional NPTW, it has one more adjustable infusion solution, which will be introduced into the wound bed during the treatment, and the wound will be infiltrated and washed by the solution. NPTWi can flexibly adjust the type and volume of solution, as well as the residence time of solution on the wound surface, complete wound cleaning and care in a negative pressure sealed environment, improve the wound healing microenvironment, and can further reduce the biological load of the wound bed by adding antibiotics to the liquid. 74 There was evidence that NPWTi is superior to standard NPWT in the treatment of diabetic infections after surgical debridement. However, the quality of evidence for the use of NPWTi in the treatment of diabetic foot infections is limited and comes primarily from cases, small retrospective or prospective studies. 75 The optimal drip regimen, optimal fluid residence time, and negative pressure time for NPWTi also need to be further explored.

Another development direction for NPTW is to improve compliance and reduce costs. The Smart Negative Pressure (SNaP) Wound Care System (Spiracur, Sunnyvale, CA) and the PICO Negative Pressure Wound Treatment System (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN) are two new systems on the market that are disposable, portable, quiet, and less disruptive to patients' daily lives, which are disposable, portable, quiet, and less disruptive to patients' daily lives and are expected to have a more important therapeutic and commercial value in ambulatory patients. 74

The in‐depth study on the mechanism of NPTW promoting healing has improved people's understanding of DFU. Younan et al. described the promoting effect of NPTW on the expression of nerve growth factor by changing the micromechanical force on the wound surface, explaining the reason why NPTW promotes wound formation from a novel perspective. 76 The experiments of Seo et al. demonstrated that NPTW promoted endothelial progenitor cell mobilisation systemically and increased vascular and granulation tissue generation. 77 Experiments by Valentina et al. demonstrated that NPTW was able to regulate protease activity, thereby promoting chronic diabetic wound healing by influencing extracellular matrix proliferation and remodelling. 78 The molecular mechanism of NPTW promoting wound healing has also made some progress. Wang et al. collected from patients who had received NPWT or SOC. Through histological and immunohistochemical analysis, reached a preliminary conclusion that NPWT may act by inhibiting the pro‐inflammatory enzyme activating transcription factor‐3 (ATF‐3) and the (inhibitor of nuclear factor‐kappaB) IκB‐α. 79 , 80 Further understanding of the pathogenesis of DFU will further promote the innovation of DFU treatment.

3.2.3. Oxygen therapy

All stages of diabetic wound healing rely heavily on oxygen. However, DFU causes ischemia and necrosis of wound tissue, and there are not enough blood vessels to transport blood to the wound to provide energy for healing, which limits the self‐repair and immune function of skin cells. The hypoxic environment also promotes the growth of anaerobic bacteria, which is detrimental to wound healing. 81 The purpose of oxygen therapy is to compensate for DFU patients' lack of oxygen.

At present, there are two main types of oxygen therapy. The first is systemic hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), which requires patients to breathe or make whole‐body contact with concentrated oxygen under pressure higher than an absolute atmospheric (ATA). By increasing the oxygen supply and distribution in damaged tissues, regulating immunity, stimulating granulation tissue, blood vessels, and collagen production, to achieve the effect of promoting wound healing, especially the healing of Wagner grade 3 and 4 DFU, 82 , 83 and reducing the possibility of major amputation. 84 , 85 The other method is Topical oxygen therapies (TOTs), which deliver oxygen directly to the open wound. 86 Compared with systemic HBOT, it has the advantages of strong patient compliance, small equipment footprint, and low cost. 70 , 87 , 88

Oxygen therapy for diabetic wounds is still controversial, 89 and a large number of large, strictly designed and implemented randomised controlled trials are still required to clarify the value of oxygen therapy in the treatment of DFU. 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 At the same time, the confined, high‐pressure oxygen environment for treating diabetic foot produces, close to one in 10 000 side effects, including various forms of pneumatic injuries, central nervous system and pulmonary oxygen toxicity, ocular side effects, and claustrophobia, making HBO poorly accepted by clinicians, despite the fact that all of these side effects can be treated with reasonable care without long‐term sequelae for patients. 94 In addition, the high cost and the tedious and time‐consuming treatment process are also important reasons that hinder the popularisation and development of HBO in clinical practice. 95 , 96

3.3. Energy‐based physical therapy

Wound healing is an energy‐demanding process that often requires the assistance of physical therapy, which accelerates and optimises the repair process by shortening the absorption time of the implant and improving the quality of healing. 97 Non‐traditional physical therapy focuses on changes in the microenvironment of chronic wounds than traditional physical therapy and accelerates wound healing through a variety of biochemical mechanisms. 98 Energy‐based physical therapy for DFU mainly includes the following: shockwave therapy, extremely low‐frequency magnetic field stimulation, electrical stimulation (ES) and photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT). ES and PBMT are widely used in clinical practice.

3.3.1. Electrical stimulation

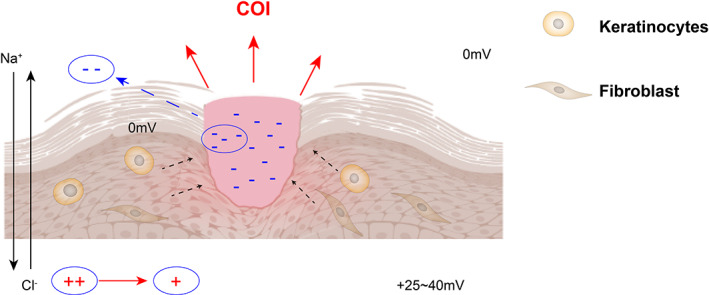

The intact skin will present a trans‐epithelial potential, primarily in the form of anions and cations exchanged between the dermis and the epidermis, known as the ‘skin battery’, and skin damage will cause leakage of the ‘skin battery’, resulting in a current of injury (COI). COI is an endogenous electric field, and electrotaxis will cause skin cells to move to the center of the electric field (Figure 3). The theory suggests that continuous COI is a prerequisite for cell migration and wound healing. 99 In contrast, hyperglycemia in DFU patients retards wound healing by inhibiting COI and decreasing the activity of cells involved in the healing cascade. ES is a non‐invasive, inexpensive, and easy‐to‐use physical therapy that mimics and enhances the COI to re‐establish skin cell migration. 99 ES also increases local blood flow to the skin, which aids in the exchange of substances between the wound and the blood, thereby speeding up wound healing. 100 , 101 ES is superior to traditional antibacterial medications that promote wound healing because they do not cause bacterial resistance. 102 Using metal antibacterial materials on the basis of ES can greatly improve the antibacterial effect. 98 Furthermore, ES can significantly reduce patients' sensory threshold and increase their perception of skin damage while reducing pain, but a large number of high‐quality experiments are still needed to prove this view. 101 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106

FIGURE 3.

The mechanism of generation of wound electric fields. COI, Current of Injury. Skin cells are recruited to the wound under the action of endogenous electric field formed by COI.

To ensure the unidirectional movement of the current, the ES stimulation generally uses direct current or pulsed current (PC), resulting in positive and negative electrodes. Polak et al. summarised and the results of high‐voltage pulsed current (HVPC) treatment of chronic wounds and found that both positive and negative electrodes can promote wound healing, and different electrodes can play a role in different stages of wound healing. The anode can play a role in the inflammatory stage of wound healing, and improve the response and efficiency of the inflammatory stage by activating the electrotaxis of immune cells; Cathode can promote the release of wound surface's hypoxic inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐α), nitric oxide (NO) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stimulate the formation of wound epithelial cells. 107 Based on the above experimental results, Polak et al. proposed a hypothesis that applying anodic stimulation for the first 3 days in ES treatment of chronic wounds and then switching to cathodic stimulation for the remainder of the treatment may produce a stronger pro‐healing effect. 100

Temperature is one of the most important factors influencing the effectiveness of ES treatment, and a clinical study by Petrofsky et al. found that increasing the skin temperature of the foot from 31 to 37°C accelerated wound healing after ES stimulation, primarily in the form of a substantial increase in blood flow around the wound, whereas the effect of ES alone was not significant. 108 Although there was evidence that systemic heating is more effective than topical heating, maintaining such high room temperatures in a hospital setting is impractical, so topical heating remains the preferred treatment method for heating combined with ES. 109

Currently, developing personalised medical services to achieve low cost, portability, and stability of ES devices has become a popular topic. Researchers have proposed numerous novel strategies for improving ES devices in response to these requirements, and some new micro ES devices are being developed. 110 Wireless microcurrent stimulation (WMCS) realises the innovation of ES. First, WMCS leverages the capabilities of oxygen and nitrogen to deliver electrons to generate DC with very low intensity in the wound instead of the power supply device required by regular ES. WMCS is non‐contact, so it is essentially painless and simple to use. In a large clinical experiment conducted by Wirsing et al., WMCS technology significantly accelerated the healing of refractory wounds caused by different causes. 111

Although ES has shown great potential in the treatment of DFU, it is rarely used in clinical practice. A large number of high‐quality experiments are still required to demonstrate the advantages of ES over traditional DFU treatment methods. The treatment of ES should also be standardised in order to facilitate clinical dissemination and popularisation.

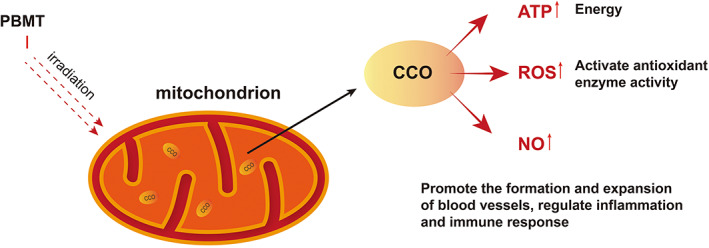

3.3.2. Photobiomodulation therapy

PBMT transmits non‐thermal light energy to cells via non‐ionising light radiation such as visible red light or near‐infrared light, and achieves photobiological regulation by changing the redox potential of cell mitochondria for pain relief, inflammation control, immune modulation, and skin tissue regeneration 112 (Figure 4). Low‐level lasers and LED lights are common to light sources in PBMT. Because of the superior therapeutic effect of laser in PBMT, 113 this method was originally also known as low‐level laser therapy. This method was first discovered and proved by Mester et al. 114 , 115 , 116 Power density (mW/cm2), wavelength (nm), energy density (J/cm2), and irradiation time(s) all influence the therapeutic effect of PBMT. 117 , 118 PBMT has been shown in numerous studies to enhance the anti‐inflammatory and antioxidant capacity of skin tissue, improve the activities of cytochrome C oxidase and metalloproteinase, promote the metabolic activity, proliferation, differentiation, migration and synthesis of collagen type I (Col‐I) of skin cells, and improve the proliferation and remodelling of wounds. 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 PBMT can also improve blood circulation, increase microvessel formation and reduce pain in patients. 124 , 125 , 126 PBMT can even be used as photodynamic therapy to reduce bacterial infection on the wound surface and accelerate the inflammatory stage of wound healing, 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 which has high clinical application value. The newly approved home PBMT device by Health Canada (B‐Cure laser Pro; Good Energies, Haifa, Israel) will enable DFU self‐treatment, which will greatly improve the compliance of patients to PBMT and reduce the medical cost of PBMT. 132 With the passage of time, the mechanism and method of PBMT promoting DFU healing have been further supplemented and improved. Gai et al. found that PBMT can promote human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) survival, proliferation, and migration by activating the VEGFA/VEGFR2/STAT3 pathway under appropriate photodynamic parameters (632.8 nm, 1.0 J/cm2), promoting wound angiogenesis and wound healing in rats. 133 Salvi et al. demonstrated the promotion and improvement of PBMT on autonomic nerve regulation, and emphasised the importance of photodynamic parameters in PBMT. 134 Mokoena et al. found that 660 nm and 5 J/cm2 PBMT promoted the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in diabetic‐injured cells. 135 Some experiments have even shown that PBMT can directly control blood glucose levels by inducing muscle glycogen synthesis. 136 The use of PBMT in conjunction with other drugs to treat DFU has begun to gain attention. Amini et al. demonstrated that the combination of conditioned medium (CM) from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with pulse wave PBM in a rat model of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) promoted wound healing. It was proved that CM + PBM significantly increased the expression of Basic FGF, Stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 α (SDF‐1), and HIF‐1α in the wounds of T1DM rats. 137 The synergistic therapeutic effects of drugs such as curcumin and metformin, which can help with diabetic wound healing and PBMT have also begun to be studied and achieved the expected results. 129 , 138 In the current PBMT combination therapy, the combination of PBMT and adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD‐MSC) in the treatment of DFU appears to be a hot spot. There is substantial animal experimental data to show that the treatment method significantly improves the healing of diabetic wounds and other chronic wounds. 139 , 140 , 141 , 142

FIGURE 4.

Mechanism of action of PBM therapy in wound healing. PBMT, photobiomodulation therapy; I, irradiation; CCO, cytochrome c oxidase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NO, Nitric Oxide.

Not all DFU are candidates for PBTM, and DFU patients with severe infection, ischemia, or combined systemic disease need to be excluded before using PBM. PBMT may only be significantly effective in the healing of Wagner grade 1 and 2 DFUs. 143 Furthermore, animal studies may not replicate the real clinical situation of DFU patients, and well‐designed human studies are still the gold standard in clinical practice. 144

4. CONCLUSION AND PROSPECT

For additional requirements for specific article types and further information please refer to ‘Article types’ on every Frontiers journal page. The proportion of DFU treatment in medical spending is also rising year after year as a result of the population's aging problem and the rise in diabetic patients. As a result, it's important to enhance DFU treatment methods, lower DFU treatment costs, increase patient awareness of the harm caused by DFU, improve patient adherence to the DFU treatment process, and move the ‘main battlefield’ of DFU prevention and treatment from the hospital to the patient's home. In addition to lowering the cost of diabetic care, preventive and ambulatory treatment approaches also result in a more effective utilisation of hospital medical resources. In‐depth study of the pathogenesis of DFU has made reasonable exercise and eating habits re‐emphasised, which has greatly improved the quality of life of DFU patients and promoted the cure of DFU. With the continuation of clinical practice and the improvement of technology, physical therapy is becoming more and more standardised and humanised. More and more portable and home‐based therapeutic instruments have been developed and popularised. DFU patients can self‐treat at home, which not only improves the compliance of patients but also avoids the cost of patients going to hospital for treatment and the secondary injury of foot before DFU treatment. ES and PBMT are relatively new but not yet mature treatments, and their clinical application potential has yet to be explored in comparison to other traditional physical therapies.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (19 401 900 700, 20S21901200, 20DZ2255200, 21 140 901 900, 21S21900900, and 22S2190270), and Special Plan for Innovation and Generation of Military Medical Support Capability (20WQ011)

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. Miao and Mr. Chen for proofreading this review.

Huang H, Xin R, Li X, et al. Physical therapy in diabetic foot ulcer: Research progress and clinical application. Int Wound J. 2023;20(8):3417‐3434. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14196

Hao Huang and Rujuan Xin contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Zongguang Tai, Email: taizongguang@163.com.

Leilei Bao, Email: annabao212@126.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data openly available in a public repository that issues datasets with DOIs.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chang M, Nguyen TT. Strategy for treatment of infected diabetic foot ulcers. Acc Chem Res. 2021;54(5):1080‐1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country‐level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harding JL, Benoit SR, Gregg EW, Pavkov ME, Perreault L. Trends in rates of infections requiring hospitalization among adults with versus without diabetes in the U.S., 2000‐2015. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(1):106‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fitridge R, Pena G, Mills JL. The patient presenting with chronic limb‐threatening ischaemia. Does diabetes influence presentation, limb outcomes and survival? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polk C, Sampson MM, Roshdy D, Davidson LE. Skin and soft tissue infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2021;35(1):183‐197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sen CK. Human wound and its burden: updated 2020 compendium of estimates. Adv Wound Care. 2021;10(5):281‐292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dayya D, O'Neill OJ, Huedo‐Medina TB, Habib N, Moore J, Iyer K. Debridement of diabetic foot ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 2021;11(12): 666‐686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bus SA, van Netten JJ, Monteiro‐Soares M, Lipsky BA, Schaper NC. Diabetic foot disease: ‘the times they are a Changin'’. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Phang SJ, Arumugam B, Kuppusamy UR, Fauzi MB, Looi ML. A review of diabetic wound models‐novel insights into diabetic foot ulcer. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;15(12):1051‐1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lung CW, Wu FL, Liao F, Pu F, Fan Y, Jan YK. Emerging technologies for the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2020;29(2):61‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schaper NC, van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J, Bus SA, Hinchliffe RJ, Lipsky BA. Practical guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oliveira A, Simoes S, Ascenso A, Reis CP. Therapeutic advances in wound healing. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(1):2‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mariadoss AVA, Sivakumar AS, Lee CH, Kim SJ. Diabetes mellitus and diabetic foot ulcer: etiology, biochemical and molecular based treatment strategies via gene and nanotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151:113134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2367‐2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blair MJ, Jones JD, Woessner AE, Quinn KP. Skin structure‐function relationships and the wound healing response to intrinsic aging. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2020;9(3):127‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Versey Z, da Cruz Nizer WS, Russell E, et al. Biofilm‐innate immune Interface: contribution to chronic wound formation. Front Immunol. 2021;12:648554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Louiselle AE, Niemiec SM, Zgheib C, Liechty KW. Macrophage polarization and diabetic wound healing. Transl Res. 2021;236:109‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Munoz LD, Sweeney MJ, Jameson JM. Skin resident γδ T cell function and regulation in wound repair. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):9286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharma S, Schaper N, Rayman G. Microangiopathy: is it relevant to wound healing in diabetic foot disease? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot: from art to science. The 18th Camillo Golgi lecture. Diabetologia. 2004;47(8):1343‐1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu SC, Jensen JL, Weber AK, Robinson DE, Armstrong DG. Use of pressure offloading devices in diabetic foot ulcers: do we practice what we preach? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2118‐2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lavery LA, Higgins KR, La Fontaine J, Zamorano RG, Constantinides GP, Kim PJ. Randomised clinical trial to compare total contact casts, healing sandals and a shear‐reducing removable boot to heal diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12(6):710‐715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ababneh A, Finlayson K, Edwards H, Lazzarini PA. Factors associated with adherence to using removable cast walker treatment among patients with diabetes‐related foot ulcers. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2022;10(1):e002640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Götz J, Lange M, Dullien S, et al. Off‐loading strategies in diabetic foot syndrome‐evaluation of different devices. Int Orthop. 2017;41(2):239‐246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Faglia E, Caravaggi C, Clerici G, et al. Effectiveness of removable walker cast versus nonremovable fiberglass off‐bearing cast in the healing of diabetic plantar foot ulcer: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1419‐1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Armstrong DG, Short B, Espensen EH, Abu‐Rumman PL, Nixon BP, Boulton AJ. Technique for fabrication of an ‘instant total‐contact cast’ for treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92(7):405‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piaggesi A, Macchiarini S, Rizzo L, et al. An off‐the‐shelf instant contact casting device for the management of diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized prospective trial versus traditional fiberglass cast. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(3):586‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elraiyah T, Prutsky G, Domecq JP, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of off‐loading methods for diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(2 Suppl):59S‐68S e1‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crews RT, Candela J. Decreasing an offloading device's size and offsetting its imposed limb‐length discrepancy lead to improved comfort and gait. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):1400‐1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Waaijman R, Keukenkamp R, de Haart M, Polomski WP, Nollet F, Bus SA. Adherence to wearing prescription custom‐made footwear in patients with diabetes at high risk for plantar foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1613‐1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Waaijman R, de Haart M, Arts ML, et al. Risk factors for plantar foot ulcer recurrence in neuropathic diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1697‐1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horstink KA, van der Woude LHV, Hijmans JM. Effects of offloading devices on static and dynamic balance in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(2):325‐335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lazzarini PA, Jarl G, Gooday C, et al. Effectiveness of offloading interventions to heal foot ulcers in persons with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Netten JJ, Sacco ICN, Lavery LA, et al. Treatment of modifiable risk factors for foot ulceration in persons with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamola G, Venturi M, Martelli D, et al. Quantitative assessment of early biomechanical modifications in diabetic foot patients: the role of foot kinematics and step width. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2015;12:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Allet L, Armand S, de Bie RA, et al. The gait and balance of patients with diabetes can be improved: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2010;53(3):458‐466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mueller MJ. Mobility advice to help prevent re‐ulceration in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kwan YH, Cheng TY, Yoon S, et al. A systematic review of nudge theories and strategies used to influence adult health behaviour and outcome in diabetes management. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(6):450‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue adaptation to physical stress: a proposed ‘physical stress theory’ to guide physical therapist practice, education, and research. Phys Ther. 2002;82(4):383‐403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crews RT, Schneider KL, Yalla SV, Reeves ND, Vileikyte L. Physiological and psychological challenges of increasing physical activity and exercise in patients at risk of diabetic foot ulcers: a critical review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(8):791‐804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Williams PT, Franklin B. Vigorous exercise and diabetic, hypertensive, and hypercholesterolemia medication use. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(11):1933‐1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kanade RV, van Deursen RW, Harding K, Price P. Walking performance in people with diabetic neuropathy: benefits and threats. Diabetologia. 2006;49(8):1747‐1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sacco IC, Sartor CD. From treatment to preventive actions: improving function in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl 1):206‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhao Y, Cai K, Wang Q, Hu Y, Wei L, Gao H. Effect of tap dance on plantar pressure, postural stability and lower body function in older patients at risk of diabetic foot: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1):e001909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Basiri R, Spicer MT, Levenson CW, Ormsbee MJ, Ledermann T, Arjmandi BH. Nutritional supplementation concurrent with nutrition education accelerates the wound healing process in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Biomedicine. 2020;8(8):263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Molnar JA, Vlad LG, Gumus T. Nutrition and chronic wounds: improving clinical outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(3 Suppl):71S‐81S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Basiri R, Spicer M, Levenson C, Ledermann T, Akhavan N, Arjmandi B. Improving dietary intake of essential nutrients can ameliorate inflammation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Nutrients. 2022;14(12):2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mohseni S, Bayani M, Bahmani F, et al. The beneficial effects of probiotic administration on wound healing and metabolic status in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34(3). doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yammine K, Wehbe R, Assi C. A systematic review on the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(10):2970‐2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bechara N, Gunton JE, Flood V, Hng TM, McGloin C. Associations between nutrients and foot ulceration in diabetes: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Farah S, Yammine K. A systematic review on the efficacy of vitamin B supplementation on diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(5):1340‐1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moore ZE, Corcoran MA, Patton D. Nutritional interventions for treating foot ulcers in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD011378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Strauss MB. Surgical treatment of problem foot wounds in patients with diabetes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;439:91‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Golinko MS, Joffe R, Maggi J, et al. Operative debridement of diabetic foot ulcers. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(6):e1‐e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Suh HS, Oh TS, Hong JP. Innovations in diabetic foot reconstruction using supermicrosurgery. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl 1):275‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411(1):153‐165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bergin SM, Gurr JM, Allard BP, et al. Australian diabetes foot network: management of diabetes‐related foot ulceration ‐ a clinical update. Med J Aust. 2012;197(4):226‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hong JP. Reconstruction of the diabetic foot using the anterolateral thigh perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(5):1599‐1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wilcox JR, Carter MJ, Covington S. Frequency of debridements and time to heal: a retrospective cohort study of 312 744 wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(9):1050‐1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liu Y, Shi Y, Zhu J, et al. Study on the effect of the five‐in‐one comprehensive limb salvage Technologies of Treating Severe Diabetic Foot. Adv Wound Care. 2020;9(12):676‐685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McCardle JE. Versajet hydroscalpel: treatment of diabetic foot ulceration. Br J Nurs. 2006;15(15):S12‐S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hinchliffe RJ, Valk GD, Apelqvist J, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):S119‐S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Game FL, Apelqvist J, Attinger C, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to enhance healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl 1):154‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rayman G, Vas P, Dhatariya K, et al. Guidelines on use of interventions to enhance healing of chronic foot ulcers in diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Braun LR, Fisk WA, Lev‐Tov H, Kirsner RS, Isseroff RR. Diabetic foot ulcer: an evidence‐based treatment update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15(3):267‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Eneroth M, van Houtum WH. The value of debridement and vacuum‐assisted closure (V.a.C.) therapy in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):S76‐S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rauwerda JA. Surgical treatment of the infected diabetic foot. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20(Suppl 1):S41‐S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vikatmaa P, Juutilainen V, Kuukasjarvi P, Malmivaara A. Negative pressure wound therapy: a systematic review on effectiveness and safety. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36(4):438‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang J, Hu ZC, Chen D, Guo D, Zhu JY, Tang B. Effectiveness and safety of negative‐pressure wound therapy for diabetic foot ulcers: a meta‐analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(1):141‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1704‐1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Blume PA, Walters J, Payne W, Ayala J, Lantis J. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum‐assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):631‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schintler MV. Negative pressure therapy: theory and practice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):72‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Markakis K, Bowling FL, Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot in 2015: an overview. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl 1):169‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Garwood CS, Steinberg JS. What's new in wound treatment: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl 1):268‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Singh D, Chopra K, Sabino J, Brown E. Practical things you should know about wound healing and vacuum‐assisted closure management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(4):839e‐854e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Younan G, Ogawa R, Ramirez M, Helm D, Dastouri P, Orgill DP. Analysis of nerve and neuropeptide patterns in vacuum‐assisted closure‐treated diabetic murine wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(1):87‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Seo SG, Yeo JH, Kim JH, Kim JB, Cho TJ, Lee DY. Negative‐pressure wound therapy induces endothelial progenitor cell mobilization in diabetic patients with foot infection or skin defects. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45:e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Izzo V, Meloni M, Giurato L, Ruotolo V, Uccioli L. The effectiveness of negative pressure therapy in diabetic foot ulcers with elevated protease activity: a case series. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6(1):38‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wang T, He R, Zhao J, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy inhibits inflammation and upregulates activating transcription factor‐3 and downregulates nuclear factor‐kappaB in diabetic patients with foot ulcerations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(4). doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Khamaisi M, Balanson S. Dysregulation of wound healing mechanisms in diabetes and the importance of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(7). doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nasole E, Nicoletti C, Yang ZJ, et al. Effects of alpha lipoic acid and its R+ enantiomer supplemented to hyperbaric oxygen therapy on interleukin‐6, TNF‐alpha and EGF production in chronic leg wound healing. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2014;29(2):297‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kranke P, Bennett M, Roeckl‐Wiedmann I, Debus S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD004123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Dhamodharan U, Karan A, Sireesh D, et al. Tissue‐specific role of Nrf2 in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers during hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;138:53‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Game FL, Hinchliffe RJ, Apelqvist J, et al. A systematic review of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):119‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Liu R, Li L, Yang M, Boden G, Yang G. Systematic review of the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygenation therapy in the management of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(2):166‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Vas P, Rayman G, Dhatariya K, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to enhance healing of chronic foot ulcers in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Frykberg RG, Franks PJ, Edmonds M, et al. A multinational, multicenter, randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of cyclical topical wound oxygen (TWO2) therapy in the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: the TWO2 study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(3):616‐624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yellin JI, Gaebler JA, Zhou FF, et al. Reduced hospitalizations and amputations in patients with diabetic foot ulcers treated with cyclical pressurized topical wound oxygen therapy: real‐world outcomes. Adv Wound Care. 2022:11(12):657‐665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fedorko L, Bowen JM, Jones W, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy does not reduce indications for amputation in patients with diabetes with nonhealing ulcers of the lower limb: a prospective, double‐blind, randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(3):392‐399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Aldana PC, Khachemoune A. Diabetic foot ulcers: appraising standard of care and reviewing new trends in management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(2):255‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Londahl M, Boulton AJM. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in diabetic foot ulceration: useless or useful? A battle. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Stoekenbroek RM, Santema TB, Legemate DA, Ubbink DT, van den Brink A, Koelemay MJ. Hyperbaric oxygen for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47(6):647‐655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Flegg JA, McElwain DL, Byrne HM, Turner IW. A three species model to simulate application of hyperbaric oxygen therapy to chronic wounds. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(7):e1000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Heyboer M 3rd, Sharma D, Santiago W, McCulloch N. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: side effects defined and quantified. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6(6):210‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot wounds: has hope hurdled hype? Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1143‐1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Londahl M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):78‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Neves LMG, Parizotto NA, Cominetti MR, Bayat A. Photobiomodulation of a flowable matrix in a human skin ex vivo model demonstrates energy‐based enhancement of engraftment integration and remodeling. J Biophotonics. 2018;11(9):e201800077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ennis WJ, Lee C, Gellada K, Corbiere TF, Koh TJ. Advanced technologies to improve wound healing: electrical stimulation, vibration therapy, and ultrasound‐what is the evidence? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(3 Suppl):94S‐104S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Melotto G, Tunprasert T, Forss JR. The effects of electrical stimulation on diabetic ulcers of foot and lower limb: a systematic review. Int Wound J. 2022;19:1911‐1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Polak A, Franek A, Taradaj J. High‐voltage pulsed current electrical stimulation in wound treatment. Adv Wound Care. 2014;3(2):104‐117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Peters EJ, Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Fleischli JG. Electric stimulation as an adjunct to heal diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(6):721‐725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yadav A, Gupta A. Noninvasive red and near‐infrared wavelength‐induced photobiomodulation: promoting impaired cutaneous wound healing. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2017;33(1):4‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Najafi B, Crews RT, Wrobel JS. A novel plantar stimulation technology for improving protective sensation and postural control in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a double‐blinded, randomized study. Gerontology. 2013;59(5):473‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kwan RL, Cheing GL, Vong SK, Lo SK. Electrophysical therapy for managing diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. Int Wound J. 2013;10(2):121‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zhou K, Schenk R, Brogan MS. The wound healing trajectory and predictors with combined electric stimulation and conventional care: one outpatient wound care clinic's experience. Eur J Clin Investig. 2016;46(12):1017‐1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Harris C, Ramage D, Boloorchi A, Vaughan L, Kuilder G, Rakas S. Using a muscle pump activator device to stimulate healing for non‐healing lower leg wounds in long‐term care residents. Int Wound J. 2019;16(1):266‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Asadi MR, Torkaman G, Hedayati M, Mohajeri‐Tehrani MR, Ahmadi M, Gohardani RF. Angiogenic effects of low‐intensity cathodal direct current on ischemic diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;127:147‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Petrofsky JS, Lawson D, Berk L, Suh H. Enhanced healing of diabetic foot ulcers using local heat and electrical stimulation for 30 min three times per week. J Diabetes. 2010;2(1):41‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Petrofsky JS, Lawson D, Suh HJ, et al. The influence of local versus global heat on the healing of chronic wounds in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9(6):535‐544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Luo R, Dai J, Zhang J, Li Z. Accelerated skin wound healing by electrical stimulation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(16):e2100557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wirsing PG, Habrom AD, Zehnder TM, Friedli S, Blatti M. Wireless micro current stimulation‐an innovative electrical stimulation method for the treatment of patients with leg and diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12(6):693‐698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Karkada G, Maiya GA, Houreld NN, et al. Effect of photobiomodulation therapy on inflammatory cytokines in healing dynamics of diabetic wounds: a systematic review of preclinical studies. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2020;1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Vitoriano NAM, Mont'Alverne DGB, Martins MIS, et al. Comparative study on laser and LED influence on tissue repair and improvement of neuropathic symptoms during the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Lasers Med Sci. 2019;34(7):1365‐1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Mester E, Sellyei M, Tota J. The effect of laser beam on Ehrlich ascites tumor cells in vitro. Orv Hetil. 1968;109(46):2551‐2552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Mester E, Spiry T, Szende B, Tota JG. Effect of laser rays on wound healing. Am J Surg. 1971;122(4):532‐535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Mester E, Mester AF, Mester A. The biomedical effects of laser application. Lasers Surg Med. 1985;5(1):31‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Zhou Y, Chia HWA, Tang HWK, et al. Efficacy of low‐level light therapy for improving healing of diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Wound Repair Regen. 2021;29(1):34‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Nair HKR, Chong SSY, Selvaraj DDJ. Photobiomodulation as an adjunct therapy in wound healing. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2021;15347346211004186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Goralczyk K, Szymanska J, Gryko L, Fisz J, Rosc D. Low‐level laser irradiation modifies the effect of hyperglycemia on adhesion molecule levels. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(7):1521‐1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ayuk SM, Houreld NN, Abrahamse H. Collagen production in diabetic wounded fibroblasts in response to low‐intensity laser irradiation at 660 nm. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(12):1110‐1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ayuk SM, Abrahamse H, Houreld NN. The role of matrix Metalloproteinases in diabetic wound healing in relation to Photobiomodulation. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2897656‐2897659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Jere SW, Houreld NN, Abrahamse H. Effect of photobiomodulation on cellular migration and survival in diabetic and hypoxic diabetic wounded fibroblast cells. Lasers Med Sci. 2021;36(2):365‐374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Otterco AN, Andrade AL, Brassolatti P, Pinto KNZ, Araujo HSS, Parizotto NA. Photobiomodulation mechanisms in the kinetics of the wound healing process in rats. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;183:22‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Saied GM, Kamel RM, Labib AM, Said MT, Mohamed AZ. The diabetic foot and leg: combined He‐Ne and infrared low‐intensity lasers improve skin blood perfusion and prevent potential complications. A prospective study on 30 Egyptian patients. Lasers Med Sci. 2011;26(5):627‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Mathur RK, Sahu K, Saraf S, Patheja P, Khan F, Gupta PK. Low‐level laser therapy as an adjunct to conventional therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(2):275‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Romanelli M, Piaggesi A, Scapagnini G, et al. EUREKA study ‐ the evaluation of real‐life use of a biophotonic system in chronic wound management: an interim analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:3551‐3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Kouhkheil R, Fridoni M, Piryaei A, et al. The effect of combined pulsed wave low‐level laser therapy and mesenchymal stem cell‐conditioned medium on the healing of an infected wound with methicillin‐resistant staphylococcal aureus in diabetic rats. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(7):5788‐5797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]