Abstract

It was recently reported that Streptococcus iniae, a bacterial pathogen of aquatic animals, can cause serious disease in humans. Using the chaperonin 60 (Cpn60) gene identification method with reverse checkerboard hybridization and chemiluminescent detection, we identified correctly each of 12 S. iniae samples among 34 aerobic gram-positive isolates from animal and clinical human sources.

Streptococcus iniae was first isolated from skin lesions of freshwater dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) in the mid-1970s (8). In the 1980s, a new Streptococcus species, causing acute meningoencephalitis with mortalities as high as 50%, was isolated from infected rainbow trout (Onchorynchus mykiss) and diseased tilapia (Oreochromis species) farmed in Israel, Taiwan, and the United States (3, 4). This pathogen, which was named Streptococcus shiloi, was subsequently shown to be genetically and phenotypically identical to S. iniae. It has been suggested that the original name, S. iniae, be retained (2). The first reported case of human disease caused by this Streptococcus species was in Texas in 1991, and a second case was found in Ottawa in 1994 (1). During the winter of 1995 to 1996, four patients were diagnosed as having acute cellulitis due to a viridans group Streptococcus (1, 10). Further diagnostic tests subsequently confirmed the identity of this common infecting pathogen as S. iniae and not a viridans group Streptococcus (1, 10). Common to these patients was their handling of fresh tilapias, a popular freshwater food fish, prior to the onset of disease. Another five cases were subsequently identified in Toronto (10). Recently, because of the awareness of this disease in Canada (1, 10), two strains (isolates 582 and 608) were isolated from patients in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Thus, there is clear evidence that this pathogen is capable not only of causing serious disease in fish and dolphins but also of being transferred to and infecting humans. It is possible that other human cases have occurred but that in such instances the causative pathogen was misidentified as one of the viridans group streptococci. Of the various Streptococcus species that can be found as normal flora on humans and animals, some species can cause disease in their hosts (9). Current conventional phenotypic identification methods for Streptococcus can easily identify opportunistic pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus agalactiae. However, the unequivocal identification of some of the other species of streptococci such as the viridans group streptococci and S. iniae can be problematic.

Phenotyping methods for the preliminary identification of S. iniae have been described previously (1), but accurate species identification requires further extensive biochemical testing which is often available only in reference laboratories. Like other streptococci, this organism appears in smears as gram-positive cocci in chains, is catalase negative and leucine aminopeptidase positive, and is susceptible to vancomycin. When the organism is incubated anaerobically, betahemolysis is clearly demonstrated. Like S. pyogenes, this species is pyrrolidonylarylamidase positive and may be susceptible to bacitracin. However, S. iniae has not been demonstrated to carry any known Lancefield group antigen. S. iniae may grow in 6.5% NaCl, but only after prolonged incubation, and does not grow on bile esculin agar. Esculin and arginine are hydrolyzed and the CAMP test is positive; the Voges-Proskauer, urease, and hippurate tests are negative. Typical strains ferment glucose, salicin, sucrose, and starch, while tests for the fermentation of arabinose, inulin, lactose, melibiose, raffinose and sorbitol are negative. Mannitol fermentation is variable. We previously provided evidence that PCR amplification of the universal chaperonin 60 (Cpn60) gene (5) with a pair of degenerate Cpn60-specific primers followed by reverse checkerboard hybridization may be a useful alternative nucleic acid-based method for identifying microbes (6, 7). The method, described in detail in reference 7, consists essentially of evenly depositing each species-specific PCR-generated 600-bp Cpn60 fragment as a 13-cm-long slot onto a nylon membrane with a minislot apparatus (Immunetics Inc., Cambridge, Mass.). The filter, following heat fixation of the DNA and prehybridization, is loaded into the miniblot setup (Immunetics Inc.) such that the immobilized DNA slots are at right angles to the hybridization channels on the miniblot apparatus. To produce hybridization probes, 600-bp regions of the Cpn60 genes from bacterial isolates are simultaneously amplified and the amplicons are labeled with digoxigenin-11–dUTP by using the degenerate pair of PCR primers (6, 7). Each probe, in hybridization buffer, is pipetted into an individual hybridization channel on the miniblot apparatus. DNA hybridization signals are detected according to Boehringer Mannheim digoxigenin chemiluminescent detection protocols and by using Kodak Biomax X-ray films.

The data reported herein demonstrate that S. iniae can be accurately identified by the Cpn60 identification method. In the initial phase of this study, one putative S. iniae isolate (isolate 288) was recovered from a swab taken from a live tilapia. It was confirmed as S. iniae by standard phenotypic methods (data not shown). To compare the specificity of our Cpn60 identification method against those of standard phenotypic methods for S. iniae identification, 34 bacterial isolates were identified by Cpn60 gene reverse checkerboard hybridization followed by chemiluminescent detection according to previously published protocols (7). The type strain, S. iniae ATCC 29178 (8), was used to generate a positive species-specific 600-bp Cpn60 target. The negative-control target streptococci, S. anginosus ATCC 33397, S. mutans ATCC 25175, S. mitis ATCC 9811, S. bovis ATCC 9809, S. salivarius 25975, S. pneumoniae ATCC 27336, S. porcinus SR1387/93, and S. equi ATCC 9528, were from the culture collection of the National Centre for Streptococcus, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. The other bacterial cultures used to generate the known 600-bp Cpn60 DNA targets shown in Fig. 1 (see the legend for Fig. 1) were from the culture collection of the Provincial Laboratory, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control. Digoxigenin-11–dUTP-labelled probes from a total of 34 isolates consisting of 31 isolates obtained in the blind from humans and animals (Table 1), S. iniae ATCC 29178, and isolates 286 and 288 were synthesized with the degenerate Cpn60-specific PCR primers (7). The miniblot apparatus was used to hybridize the probes against the panel of 600-bp Cpn60 gene targets comprising S. iniae ATCC 29178 and the 27 known bacterial negative controls (Fig. 1). Nine of the 31 isolates obtained in the blind, ATCC 29178, and isolates 286 and 288 were positive for S. iniae by the Cpn60 identification method (Fig. 1 and Table 1). No cross-hybridization against any of the negative controls, which included 10 different Streptococcus species, was observed (Fig. 1). All 12 S. iniae isolates previously had been confirmed as S. iniae by standard biochemical phenotyping methods (Table 1). Probes from the remaining 22 bacterial isolates failed to hybridize with the Cpn60 DNA targets from either S. iniae or the negative controls (Fig. 1 and Table 1). These isolates, which were recovered from tilapias, consisted of either Vagococcus or Enterococcus species, with one (9002-3) being an unidentified species (Table 1).

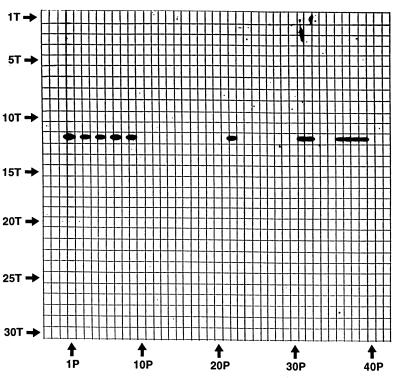

FIG. 1.

Miniblot reverse checkerboard hybridization results for bacterial isolates described in Table 1. The horizontal slots contained immobilized Cpn60 600-bp target (T) DNA from S. anginosus ATCC 29971 (2T), S. bovis ATCC 9809 (3T), S. equi ATCC 9528 (4T), S. mitis ATCC 9811 (5T), S. mutans ATCC 25175 (6T) S. pneumoniae ATCC 27336 (7T), S. porcinus SR1387/93 (8T), S. salivarius ATCC 25957 (9T), S. pyogenes ATCC 19615 (10T), S. agalactiae ATCC 12386 (11T), S. iniae ATCC 29178 (12T), Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600 (13T), Citrobacter freundii ATCC 8090 (14T), Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048 (15T), Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (16T), Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 (17T), Proteus vulgaris ATCC 13315 (18T), Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028 (19T), Serratia marcescens ATCC 8100 (20T), Shigella sonnei ATCC 25931 (21T), Neisseria gonorrhoeae ATCC 41426 (22T), Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 (23T), Yersinia enterocolitica ATCC 27729 (24T), Proteus mirabilis ATCC 25933 (25T), Staphylococcus lugdunensis ATCC 43804 (26T), Borrelia burgdorferi ATCC 53899 (27T), Streptococcus faecalis ATCC 19433 (28T), and Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 14990 (29T). Slots 1T and 30T contained no DNA. The vertical hybridization channels contained digoxigenin-labelled Cpn60 600-bp probe (P) DNA from S. iniae ATCC 29178 (1P), isolate 582 (3P), isolate 608 (5P), isolate 286 (7P), isolate 288 (9P), isolate 9001-1 (11P), isolate 9001-2 (12P), isolate 9001-3 (13P), isolate 9001-4 (14P), isolate 9002-1 (15P), isolate 9002-2 (16P), isolate 9002-3 (17P), isolate 9002-4 (18P), isolate 9003-2 (19P), isolate 9003-3 (20P), isolate 9003-4 (21P), isolate 9003-5 (22P), isolate 9004-1 (23P), isolate 9004-2 (24P), isolate 9004-3 (25P), isolate 9005-1 (26P), isolate 9005-2 (27P), isolate 9005-3 (28P), isolate 9005-4 (29P), isolate 9005-5 (30P), isolate 9005-6 (31P), isolate 9005-7 (32P), isolate 9006-1 (33P), isolate 9006-2 (34P), isolate 9006-3 (35P), isolate 9019 (36P), isolate 9020 (37P), isolate 9085 (38P), and isolate 9086 (39P). Vertical hybridization channels 2P, 4P, 6P, 8P, 10P, and 40P contained hybridization buffer alone.

TABLE 1.

Identification of S. iniae isolates by the Cpn60 Gene identification method and reverse checkerboard hybridization

| Isolate | Source | Bacterial species (by phenotype) | S. iniae result by Cpn60 Gene IDa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9001-1 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9001-2 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9001-3 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9001-4 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9002-1 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9002-2 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9002-3 | Fish | Unidentified | − |

| 9002-4 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9003-2 | Fish | Enterococcus sp. | − |

| 9003-3 | Fish | Enterococcus sp. | − |

| 9003-4 | Fish | Enterococcus sp. | − |

| 9003-5 | Fish | S. iniae | + |

| 9004-1 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9004-2 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9004-3 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9005-1 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9005-2 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9005-3 | Fish | Enterococcus sp. | − |

| 9005-4 | Fish | Enterococcus sp. | − |

| 9005-5 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9005-6 | Fish | S. iniae | + |

| 9005-7 | Fish | S. iniae | + |

| 9006-1 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9006-2 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9006-3 | Fish | Vagococcus sp. | − |

| 9019 | Dolphin | S. iniae | + |

| 9020 | Dolphin | S. iniae | + |

| 9085 | Fish | S. iniae | + |

| 9086 | Fish | S. iniae | + |

| 286 | Human | S. iniae | + |

| 288 | Fish | S. iniae | + |

| 582b | Human | S. iniae | + |

| 608b | Human | S. iniae | + |

| S. iniae ATCC 29178 | Dolphin | S. iniae | + |

ID, identification.

Isolate obtained from patient in Vancouver British Columbia, Canada.

No false negatives were observed despite the fact that the S. iniae-positive cultures were isolated from both infected animals and humans. DNA sequencing of the 600-bp Cpn60 fragment from isolate ATCC 29178, a dolphin isolate, isolate 286, a human isolate, and isolate 288, a fish isolate, showed identical DNA sequences (data not shown). This suggests that the targeted 600-bp Cpn60 gene fragment is probably well conserved among S. iniae isolates, an important factor in the specificity of the tested bacterial identification system. Data from previous studies further support this conclusion (6, 7). Results from this study suggest that S. iniae, a potentially serious zoonotic agent, may be accurately discriminated from related organisms by the Cpn60 gene identification method. Future tests of suspected S. iniae organisms isolated from new clinical cases and various fish species should further confirm the validity of the Cpn60 gene identification results reported in this paper.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the 600-bp Cpn60 DNA fragment from S. iniae ATCC 29178 has been deposited in the GenBank under accession no. AF064076.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Panchuk for DNA sequencing.

Funding was from the Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network to D.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Invasive infection due to Streptococcus iniae—Ontario, 1995–1996. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1996;45:650–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eldar A, Frelier P F, Assenta L, Varner P W, Lawhon S, Bercovier H. Streptococcus shiloi, the name of an agent causing septicemic infection in fish, is a junior synonym of Streptococcus iniae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:840–842. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eldar A, Bejerano Y, Livoff A, Horovitcz A, Bercovier H. Experimental streptococcal meningo-encephalitis in cultured fish. Vet Microbiol. 1995;43:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eldar A, Bejerano Y, Bercovier H. Streptococcus shiloi and Streptococcus difficile: two new streptococcal species causing a meningoencephalitis in fish. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis R J. Chaperonins: introductory perspective. In: Ellis R J, editor. The chaperonins. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press Inc.; 1996. pp. 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh S H, Potter S, Wood J, Hemmingsen S M, Reynolds R P, Chow A W. HSP60 gene sequences as universal targets for microbial species identification: studies with coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:818–823. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.818-823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goh S H, Santucci Z, Kloos W E, Faltyn M, George C G, Driedger D, Hemmingsen S M. Identification of Staphylococcus species and subspecies by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method and reverse checkerboard hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3116-3121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pier G B, Madin S H. Streptococcus iniae sp. nov., a beta-hemolytic streptococcus isolated from an Amazon freshwater dolphin, Inia geoffrensis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1976;26:545–553. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruoff K L. Streptococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein M R, Litt M, Kertesz D A, Wyper P, Rose D, Coulter M, McGeer A, Facklam R, Ostach C, Willey B M, Borczyk A, Low D E. Invasive infections due to a fish pathogen, Streptococcus iniae. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:589–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708283370902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]