Abstract

Introduction

In haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from a healthy donor replace the patient’s ones. Ex vivo HSC gene therapy (HSC-GT) is a form of HSCT in which HSCs, usually from an autologous source, are genetically modified before infusion, to generate a progeny of gene-modified cells. In HSCT and HSC-GT, chemotherapy is administered before infusion to free space in the bone marrow (BM) niche, which is required for the engraftment of infused cells. Here, we review alternative chemotherapy-free approaches to niche voidance that could replace conventional regimens and alleviate the morbidity of the procedure.

Sources of data

Literature was reviewed from PubMed-listed peer-reviewed articles. No new data are presented in this article.

Areas of agreement

Chemotherapy exerts short and long-term toxicity to haematopoietic and non-haematopoietic organs. Whenever chemotherapy is solely used to allow engraftment of donor HSCs, rather than eliminating malignant cells, as in the case of HSC-GT for inborn genetic diseases, non-genotoxic approaches sparing off-target tissues are highly desirable.

Areas of controversy

In principle, HSCs can be temporarily moved from the BM niches using mobilizing drugs or selectively cleared with targeted antibodies or immunotoxins to make space for the infused cells. However, translation of these principles into clinically relevant settings is only at the beginning, and whether therapeutically meaningful levels of chimerism can be safely established with these approaches remains to be determined.

Growing points

In pre-clinical models, mobilization of HSCs from the niche can be tailored to accommodate the exchange and engraftment of infused cells. Infused cells can be further endowed with a transient engraftment advantage.

Areas timely for developing research

Inter-individual efficiency and kinetics of HSC mobilization need to be carefully assessed. Investigations in large animal models of emerging non-genotoxic approaches will further strengthen the rationale and encourage application to the treatment of selected diseases.

Keywords: haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, mobilization, autologous stem cell transplantation, gene therapy, chemotherapy-free conditioning

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) consists in the partial or complete replacement of the patient’s haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), which reside in bone marrow (BM) niches, with healthy donor cells.1 As HSPCs self-maintain and give rise to multi-lineage progeny, comprising leukocytes, erythrocytes and platelets, HSCT results in long-term substitution of haematopoiesis with donor-derived cells.

HSCT is standard practice for the treatment of several non-malignant haematopoietic diseases, both genetic (e.g. immune deficiencies) and acquired (e.g. aplastic anaemia), as well as malignant diseases, e.g. leukaemia and lymphomas. HSCT is also used to rescue haematopoiesis after high-dose chemotherapy for solid tumours (e.g. sarcomas), whose haematologic toxicity would otherwise be dose limiting.2

HSCT is undoubtedly the longest, best developed and most successful cell therapy in the regenerative medicine field.3 HSCT may be summarized as follows. Firstly, HSPCs are harvested from the donor, either the patient (autologous) or a third party (allogenic). Secondly, the patient BM is conditioned, i.e. prepared to receive the HSPC graft, by depleting the resident HSPCs from their niches. Thirdly, autologous or allogenic HSPCs are infused and home to the emptied niche, where they engraft and give rise to their progeny progressively reconstituting haematopoiesis. In case of allogenic HSCT, the patient thus becomes a chimera, whereby the host and donor cells may both contribute to the haematopoietic output, each between 0 and 100%, the extremes being full donor chimerism and graft rejection.3

If the donor is allogenic, incompatibilities between the host and the donor may give rise to averse immunological reactions, due to non-self recognition. Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) is due to the graft lymphocytes attacking the recipient’s tissues1; vice versa, graft failure may arise when the recipient’s immune system attacks the HSPC graft. Characterization of the human leukocyte antigen family (HLA) of recipient and donor is used to determine the degree of immunological compatibility between them. The greater the matching, the lower the risk of adverse immunological reactions.4,5 Notably, racial minorities have harder time finding a suitable match for HSCT, resulting in poorer outcomes.5,6

HSPC sources and collection

HSPCs can be manually aspirated from the BM. Alternatively, HSPCs can be mobilized from the BM niche and collected from the peripheral blood by apheresis. In the latter case, they are called peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs). Usually, PBSCs are the preferred source, as they may be collected in larger numbers7 with a less invasive procedure and often result in prompter haematological reconstitution as compared to BM.8 Umbilical cord blood (UCB), collected at birth after clamping, is a less commonly used source of HSPCs. Whereas UCB has been shown to be less prone to give rise to GvHD and be more enriched in more primitive stem cells,9 the weight-adjusted HSPC content from a single cord may be limiting and not reaching the dose threshold required safe and prompt haematological reconstitution of a conditioned adult individual (see Conditioning Prior HSCT).5 Generally speaking, the choice of HSPC donor source depends on the availability of HLA-matched donors in the patient’s family, international BM donors’ registry, being matched donors preferred over mismatched ones. Donor characteristics, such as age, cytomegalovirus serostatus, gender, blood group, parity and weight, also play a role in the decision, along with practical factors such as the donor’s availability for harvest in the desired timeframe.5 Donor sources differ in the number of HSPCs, being lowest in UCB and highest in PBSCs; the latter are associated with faster haematological reconstitution and lower risk of graft rejection but higher risk of GvHD.5

Mobilization procedures for HSPC collection

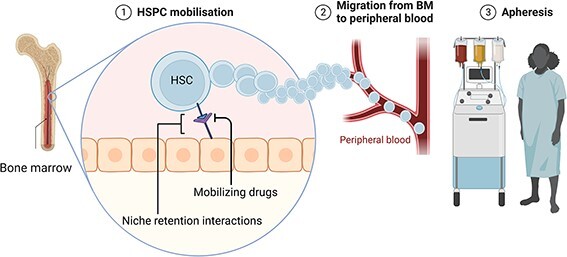

At steady state, HSPCs reside in the BM and are found in low numbers (0.01–0.05%) in circulation. Retention of HSPCs in the BM and their egression into peripheral blood are regulated by the local niche microenvironment, comprising stromal cell–expressed cytokines, growth factors and hormones, the adhesive properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the input of adrenergic nerve terminals, which contribute to instruct a circadian rhythm in the mobilization (Fig. 1). The number of circulating HSPCs can be exogenously increased through a process termed mobilization, which acts on the niche factors that retain HSPCs.10,11

Fig. 1.

HSPC collection. HSPCs reside in the BM niche, where they are retained by molecular interactions (e.g. CXCR4-CXCL12). Mobilizing drugs like lenograstim and plerixafor disrupt these interactions, and HSPCs can leave the BM niche and enter the peripheral circulation. HSPCs are then collected by apheresis.

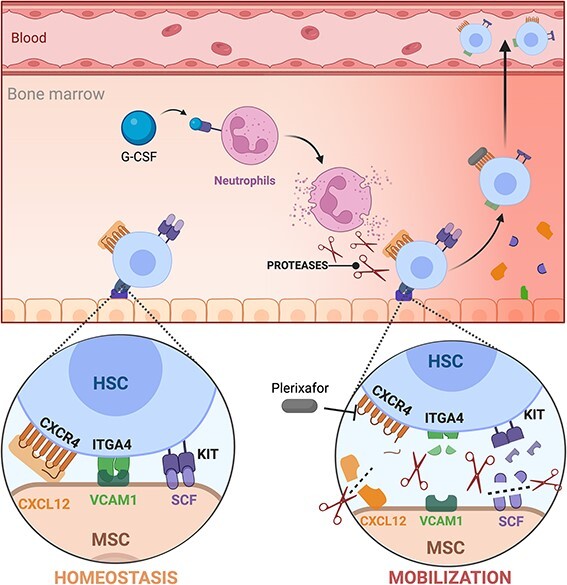

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF, e.g. lenograstim)12 is the most commonly used drug for this purpose. The mechanism of action of G-CSF in HSPC mobilization is not yet fully understood. Alone, it increases circulating PBSCs by 6–7-fold. Among other pathways, G-CSF induces the release of serine proteases (e.g. cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteinase-9) from BM neutrophils. These proteases partially digest molecules mediating cell–ECM adhesion and cell–cell interaction, such as VCAM-1, c-KIT, CXCL12 and CXCR4, which is a major homing receptor.13–15 G-CSF is administered once or twice daily for up to 6 days, either alone or in conjunction with mobilizing chemotherapy.16

G-CSF-alone mobilization may fail in up to 10% of donors. For this reason, novel molecules disrupting cell–cell interactions within the BM stem cell niche have been developed. Plerixafor (AMD3100/Mozobil®) is a competitive antagonist of CXCR4, reversibly inhibiting the key interaction between CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12. Free from the homing signal delivered by CXCL12, HSPCs egress into the periphery.17 Notably, G-CSF and plerixafor synergize in mobilizing HSPCs, reaching levels 10-fold above baseline in peripheral blood. For these reasons, plerixafor is now approved in combination with G-CSF for patients that fail to mobilize with G-CSF alone18. Of note, the relative progenitor composition of HSPC collected with G-CSF alone differ from those mobilized also with plerixafor, with the latter being more enriched in primitive progenitors and providing for faster engraftment.19–23

Other antagonists of adhesion molecules are being explored in preclinical models. Ramirez and colleagues showed that BIO5192, a VLA-4 inhibitor, antagonizes the VCAM-1/VLA-4 and results in a 30-fold increase in mobilization of murine HSPCs over basal levels.24,25 Others are investigating the use of recombinant Gro-βT (SB-251353; MGTA-145), an agonist of the CXCR2 receptor, currently in clinical testing (NCT03932864; NCT04552743; NCT05445128). It has been shown that when used in combination, Gro-β increases G-CSF or Plerixafor effects.26–28

Conditioning prior HSCT

Conditioning is administered to vacate the niche for the engraftment of donor HSPCs29. Depending on the underlying disease, conditioning regimens are tailored for providing anti-tumoral effects, immune suppression, penetration in the central nervous system and the required degree of myeloablation to establish a therapeutically effective level of chimerism.

Conditioning regimens might involve total body irradiation (TBI) and/or cytotoxic drugs, both of which are genotoxic. 29 By killing the host HSPCs, conditioning has the unescapable on-target effect of haematological suppression. In general, once conditioning has been administered, infusion of an HSPC graft is required for haematological reconstitution, which is gradual, with lineage specific kinetics. In between, patients are exposed to a very high infectious risk, mostly stemming from neutropenia, which is a major morbidity and mortality burden. 30 Red blood cells and platelet transfusions are required to ensure oxygen delivery and mitigate bleeding risk.31 Time to engraftment, which ideally is as short as possible, mostly depends on graft source, cell dose and conditioning regimen; neutrophil recovery may also be stimulated with G-CSF.32,33

Furthermore, as these cytotoxic regimens are not targeted, they have multiple short- and long-term off-target adverse effects, including vomiting, nausea, multi-organ damage, mucositis, interstitial pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, secondary tumours and infertility. The effects of conditioning regimens can vary substantially based on their mechanism of action and their intensity. Regimens may be non-myeloablative or myeloablative, depending on the partial or complete ablation of resident HSPCs.34

Ex vivo HSC-GT

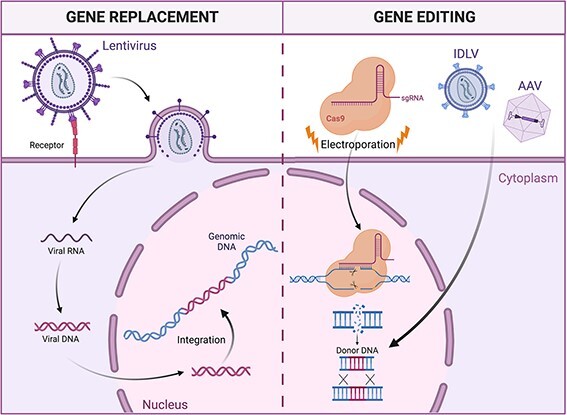

HSC-GT builds on the successful clinical track record of HSCT and the possibility to genetically modify ex vivo HSPCs for therapeutic benefit. As schematically shown in Figure 2, cells are harvested from the patient, purified and cultured ex vivo. Therapeutic genes may be delivered into the cells’ genome with viral or non-viral vectors.35,36 Alternatively, one or more endogenous genes may be edited with custom designed nucleases37–39 (Fig. 3). After conditioning, the modified cells are infused back into the patient and give rise to a genetically modified progeny. Successful gene therapies have been developed for the treatment of several congenital immune deficiencies, metabolic disorders, haemoglobinopathies and stem cell–depleting disorders. 40

Fig. 2.

Mobilization mechanism. HSPCs are retained in the BM niche by several interaction with stromal cells, as CXCL12-CXCR4, KITLG-KIT and VCAM1-ITGA4. G-CSF stimulates neutrophils to release proteases (MMP9, cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase) that cleave these receptors on both stromal cells and HSPCs, causing their release and egression into the blood stream. Plerixafor (AMD3100) acts as a competitive antagonist of CXCL12, disrupting the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis and causing the release of HSPCs. These two drugs can be used in combination to mobilize HSPCs.

Fig. 3.

Strategies for HSPC genetic modification. In gene transfer approaches (left panel), HSPCs are transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding for a functional version of the disease-causing mutated gene. Upon infection, the viral genome is retro-transcribed and integrates semi-randomly in the cell genome. In gene-editing strategies (right panel), Cas9 nuclease introduces a targeted double-strand break in the cell genome, disrupting the mutated gene. Providing a DNA template, for example, with adeno-associated viral vectors or integrase-deficient lentivirus, it is possible to trigger the homology-directed repair mechanism, introducing a functional copy of the mutated gene in a specific region of the genome.

Genetic manipulation does not come without a cost. Per se, current ex vivo manipulation procedures may negatively impact the content and fitness of gene-modified HSCs, hampering homing and their long-term repopulation potential.41,42 Moreover, not all the cells that are infused into the blood stream find their way to the stem cell niches in BM, as the majority is trapped in different non-haematopoietic organs and phagocytosed.43,44 Therefore, there is the need to develop strategies to improve homing and repopulation of the BM niche, especially when the number of engrafted HSPCs is low and their fitness is hampered.45

Chemotherapy-free replacement of HSPCs

Engraftment, as reflected by chimerism, may be thought of as a competition for occupying the ‘niche space’ between resident and transplanted cells. In absence of any preparatory regimen, transplanted HSPCs do not engraft or engraft very poorly, as the space is nearly completely occupied by resident cells.46 To a certain extent, increasing the number of infused cells, either by repeated harvests47 or ex vivo expansion before infusion,48–50 may allow establishing some chimerism, albeit to a very low level. Niche space may be vacated with chemotherapy, to an extent that depends on the intensity of the conditioning regimen (see Conditioning Prior HSCT). A fully myeloablative conditioning may eliminate most resident cells from the niche and allow infused cells engraft to substantial levels. Conversely, if not all resident cells are removed, as is the case with milder conditioning, engraftment is a competitive process between endogenous and infused HSPCs.51,52 Chemotherapy, however, also impacts stromal cells in the niche, whose damage may, in turn, affect the engraftment of the newly infused cells in different and sometimes opposite manners.53 On the one hand, niche damage may reduce the BM capacity for optimal recruitment and homing of the infused HSC. On the other hand, the secretome induced by local BM injury and depletion of its peripheral output may promote active HSC proliferation and prompt haematopoietic reconstitution.

In principle, however, removal of host HSCs does not require targeting of other cell types and tissues, nor using chemotherapy. Indeed, chemotherapy-free engraftment of genetically modified HSPCs is a highly desirable goal. Targeted removal of the recipient’s resident HSPC, increasing niche availability and increasing the competitiveness of donor cells are alternative, and possibly complementary, strategies that can be pursued to this end.

Increasing the competitiveness of donor cells

Engraftment of donor cells can be achieved in unconditioned hosts by tilting the competition between resident cells and donor cells, either by enhancing features of donor cells or exploiting defects of recipient cells.54 For instance, in mice, engraftment of wild-type HSPCs is easier if the host cells are carrying an hypomorphic c-KIT receptor, interfering with the transduction of an essential survival signal for HSC.55,56 A similar concept applies to Fanconi anaemia patients, whose HSPCs disappear over time due to inherited defects in DNA repair pathways. HSPCs that have been corrected with lentiviral gene therapy and do not suffer this impairment are thus relatively more competitive, can engraft even in the absence of conditioning and progressively expand to rescue the haematopoietic insufficiency.45

In more experimental scenarios, donor cells may be artificially endowed with an engraftment advantage by constitutively expressing CXCR4; in mouse models, this resulted in higher levels of reconstitution.57 Taken together, these observations indicate that it is at least theoretically possible to avoid the use of conditioning regimens prior to HSCT. This is even more relevant in the context of HSC-GT for diseases where partial chimerism with corrected cells is sufficient to rescue the phenotype or if corrected cells (or their progeny) can outcompete their diseased counterpart.45,58,59 For example, combined immunodeficiencies are excellent disease models for novel conditioning strategies as few engrafting HSPCs are usually sufficient to stably reconstitute T-cell immunity.59

Antibody-based conditioning

The exquisite specificity of monoclonal antibodies has been extensively investigated as a mean to selectively remove a cell population of interest. Non-genotoxic conditioning aims to make space in the BM niche without conventional chemotherapy regimens, by using safer drugs that target HSPCs while sparing non-haematopoietic cells. Surface markers such as CD45, expressed by all blood cells, or c-KIT, an HSPC marker, have been considered as prime candidates for antibody- or immunotoxin-mediated targeting. These antibodies could also be conjugated to radioactive isotope to direct the delivery of radiation specifically to the BM, allowing to maintain the efficacy of the conditioning while reducing its toxicity.60 Of note, anti-CD45 antibodies coupled with saporin—a potent toxin that halts protein synthesis—can clear the white blood cell compartment. Administration into mice prior to HSCT resulted in comparable haematopoietic reconstitution as TBI, with less side effects61 and faster T-cell repopulation likely due to sparing radio damage to the thymic stroma.59 Due to the importance of c-KIT for HSPC retention and maintenance, antibody-mediated blocking of c-Kit can deplete murine HSPCs in vivo, allowing for establishing donor chimerism levels of up to 90% after HSCT.62 Similar results have been replicated in non-human primates (NHPs), and are being tested in humans, within the context of HSCT for severe combined immunodeficiencies (NCT02963064).63 Anti-c-KIT antibodies may also be coupled with a toxin, such as saporin, increasing the efficacy (up to > 99% depletion of host HSPCs) and enabling rapid and efficient engraftment of donor HSCs.64 As the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of these antibody–drug conjugates is further refined to enable safe and efficient clinical use, their adoption for HSCT conditioning may grow to an increasingly number of indications.

Niche vacation with mobilizing agents

As mentioned above, mobilization is commonly used to free HSPCs from their niche and harvest them from the circulation. It follows that if HSPC egress from the niche, there is space that becomes available for the same—or other cells—to engraft.65 As a proof of concept, low-level engraftment (<5%) of donor cells could be achieved in parabiotic mice treated with plerixafor alone.66 Later, serial mobilization and transplantation cycles were used to engraft donor HSPCs in murine models of aging and Parkinson’s disease.67,68

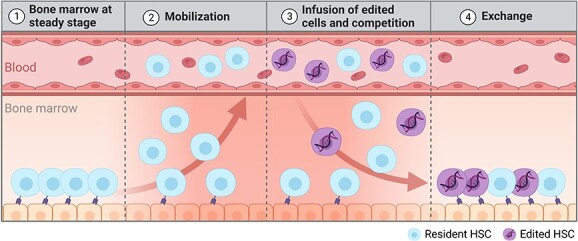

The same principle of chemotherapy-free exchange can be applied in the context of autologous HSC-GT. G-CSF, plerixafor, with or without BIO5192, can substantially, albeit transiently, empty BM niches, creating a window of opportunity for seamless engraftment of exogenous cells.65 Indeed, timely infusion of HSPCs at the peak of mobilization allows them to compete with those freshly egressed from the niche (Fig. 4). Of note, the engraftment fitness of infused and resident cells during mobilization may be different according to prior treatment. Mobilizing drugs negatively affect freshly egressed HSPCs, transiently impairing their homing and engraftment fitness due to the cleavage of homing and retention surface molecules. Conversely, cells cultured ex vivo can reconstitute the expression of the aforementioned surface receptors, thus gaining a relative competitive advantage.65

Fig. 4.

Mobilization-based conditioning strategy. After administration of the mobilization regimen, HSPCs egress the BM niche, entering in the peripheral blood (panel 2). Careful timing of the transplant at the peak of mobilization (i.e. peak of BM depletion—panel 3), enables the competition of donor cells and mobilized resident cells for the repopulation of the BM niche and an exchange between donor and resident cells (panel 4).

The principle of mobilization-based HSCT (M-HSCT) was achieved in a mouse model of Hyper IgM Syndrome I (HIGM-1), a combined immunodeficiency. HSPC exchange resulted in long-lasting stable chimerism and biologically significant restoration of immunological function.65 The applicability of this approach was further proven in human haematochimeric mice that allow the engraftment of human HSPCs in their BM niches. Human HSPCs were first transplanted in these mice and allowed to establish a human graft. Mice were then mobilized, and infused with genetically marked cells originating from the same human donor, mimicking autologous HSC-GT,65 achieving stable levels of chimerism averaging 30% of the human graft.

Intriguingly, this exchange of HSPCs can be further modified to enhance the functionality of infused cells to outcompete those in circulation. By exploiting recently optimized RNA-based delivery, a technology similar to the one exploited by common Coronavirus-19 vaccines, it is possible to transiently and safely overexpress key biological effectors in ex vivo manipulated HSPCs, in order to improve their homing and engraftment capacity. This competitive advantage resulted in higher stable long-term chimerism in haematochimeric mice.65 Furthermore, this transient enhancement of engraftment ability may also overcome detrimental impacts of ex vivo genetic manipulation on cell fitness, thus enhancing their clinical translatability.

Based on available data from clinical trials, we can estimate that the levels of chimerism with corrected cells achieved in haematochimeric mouse models, if reproduced in humans, could be adequate to provide a therapeutic benefit in many diseases currently amenable to HSPC-GT, including primary immunodeficiencies (e.g. SCID-X1, HIGM169) schiroli 2017 and possibly hemoglobinopathies and lysosomal storage disorders.

Discussion

Unresolved concerns

Usually, autologous HSC-GT protocols are deployed as follows: cells are harvested after mobilization, genetically modified and frozen for quality control assays. Once these are passed, the patient undergoes chemotherapy and then receives the drug product (DP). Prospectively, mobilization-based HSC-GT protocols need to fit into this scheme for clinical application. It is likely that HSPCs would need to be mobilized once for harvest and DP manufacturing and quality controls, and then, the patient would have to be treated again with the mobilizers right before DP infusion. However, all-in-one mobilization and engraftment protocols could be eventually devised if the ex vivo manufacturing process can be achieved within 24–48 h (as it already occurs for some current clinical studies) and qualified for reproducible and satisfactory outcome. It is conceivable that repeat administration of a stored DP could be performed in case of unsatisfactory engraftment through successive mobilization cycles, given the safety profile of the mobilization protocol.70,71 However, the kinetic of HSPC egression and recirculation during subsequent rounds of mobilization require further modelling.

Additional factors to be addressed are the following. The kinetics of HSPC mobilization and its variability in human patients must be characterized for timely infusion of the DP, given its crucial importance. If the DP is infused too early or too late, it may find the niches occupied by resident cells and thus not engraft. Combining mobilization with removal of circulating HSPCs by apheresis—the standard procedure of HSPCs collection—has not yet been modelled in the reported animal studies; in principle, it may be expected to further reduce the competition between resident and infused cells. To some extent, these questions will be best addressed in NHPs, which are considered to be the most stringent model of human HSPC physiology. Moreover, as NHPs are expected to reflect the human tissue distribution of CXCL12 better than mice, NHPs are better tailored to confirm the engraftment advantage of infused cells that are transiently overexpressing CXCR472.

Potential advantages and applications of mobilization-based conditioning

A major advantage of mobilization-based conditioning is the sparing of the immune system of the host. Thus, one would expect no neutropenia upon its application. This would avert the profound immunosuppression that follows conventional conditioning, and its short- and long-term consequences, such as mucositis, veno-occlusive disease and endocrine dysfunction, greatly shortening the morbidity and hospital stay of the procedure.29,30,73,74

Once mobilization-based HSCT has been fully validated for clinical testing, it could be first applied to HSCT settings that do not require (i) a high threshold of correction, nor (ii) lymphodepletion/immune suppression. The most suitable setting may be autologous HSC-GT for SCIDs75 and DNA repair diseases,76 which are at increased risk of chemotherapy toxicity. These diseases are usually treated with low-dose conditioning regimens, which may well be replaced by HSPC mobilization. Indeed, congenital disorders of haemopoiesis have long been excellent model diseases for the development of novel therapies and therapeutic approaches.36 Another intriguing application may be emerging HSPC-based anti-cancer therapies,77,78 which rely on the gain of function of some HSPC progeny.

Expansion to more common conditions, such as allogenic HSCT, or HSCT for malignant diseases will be far more challenging, as HSPC exchange on its own does not suppress the immune system, nor does it kill tumour cells. Different approaches could be envisioned here:

(i) combination with low-dose chemotherapy79 or (ii) combination with immune-depleting agents, both antibody based (alemtuzumab, anti-thymocyte globulin) or not (cyclophosphamide, fludarabine).

Of note, a previous trial testing G-CSF and AMD3100 as preparative regimen for patients with SCID undergoing HSCT was unsuccessful80 Retrospectively, however, the efficiency of mobilization was suboptimal7 highlighting a limited BM vacancy that would explain the low chimerism. Moreover, donor HSPCs were mobilized but not cultured ex vivo and thus most likely had reduced expression of adhesion molecules and lower homing and engraftment potential.65

Until now, genetic engineering of human haematopoiesis has been mainly approached by ex vivo strategies, which require resource-intense manufacturing processes, well-developed healthcare systems and logistical infrastructures. Yet, these features are only found in a fraction of clinical centres, precluding access to these treatments to most patients worldwide. Prospectively, mobilization protocols could transiently enhance accessibility and permissiveness of HSPCs to in vivo gene therapy, as supported by recent data obtained in mice and NHPs.28,81–83 While promising, the levels of transduction obtained so far are low (7%) and obtained following a stringent selection step, whose clinical compatibility remains to be demonstrated. Despite the challenges ahead, in vivo HSPC editing could present a major advance and allow to bypass current manufacturing challenges.

In summary, mobilization-based HSPC exchange could provide an alternative to conventional chemotherapy-based conditioning regimens, at least for the treatment of congenital diseases amenable to treatment with autologous HSC-GT. Engraftment enhancers, removal of mobilized HSPCs by apheresis, addition of new mobilization drugs and possibly antibody-conjugated immunotoxins and optimization of mRNA delivery may all help in further improving this platform and eventually broaden its applicability to more patients and diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of LN’s laboratory for discussion. The schematics were created with BioRender.com. This work was supported by grants to LN from the Telethon Foundation (SR-Tiget core grant), the Italian Ministry of Health (E-Rare-3 JTC 2017), the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN 2017 Prot. 20175XHBPN), the EU Horizon 2020 Program (UPGRADE) and from the Louis-Jeantet Foundation through the 2019 Jeantet-Collen Prize for Translational Medicine; to AO from the H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA Individual Fellowship, Grant agreement ID: 101031856); to SF from the European Hematology Association (EHA, Junior Research Grant 2022) and the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata SG-2021-12374529). GP and DC conducted this study as partial fulfilment of their PhD in Molecular Medicine, International PhD School, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University (Milan, Italy).

Contributor Information

Daniele Canarutto, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy; Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy; Pediatric Immunohematology Unit and BMT Program, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy.

Attya Omer Javed, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy.

Gabriele Pedrazzani, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy; Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy.

Samuele Ferrari, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy; Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy.

Luigi Naldini, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy; Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Via Olgettina, 60, 20132 Milano, MI, Italy.

Author contributions

Daniele Canarutto (Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Gabriele Pedrazzani (Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Samuele Ferrari (Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Luigi Naldini (Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing) and Attya Omer Javed (Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing)

Conflict of interest statement

LN is the inventor of patents on applications of gene editing in HSPCs, and compositions and methods for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, owned and managed by the San Raffaele Scientific Institute and the Telethon Foundation, including on improved gene editing filed together with by SF and DC, and increasing engraftment by HSPCs filed together with AO.

LN is the founder, quota holder and consultant of GeneSpire, a startup company developing gene therapies, including ex vivo gene editing. All other authors declare no relevant conflict of interests.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this review.

References

- 1. Comazzetto S, Shen B, Morrison SJ. Niches that regulate stem cells and hematopoiesis in adult bone marrow. Dev Cell 2021;56:1848–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galgano L, and Hutt D. Chapter 2 HSCT: How Does It Work? The European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Textbook for Nurses: Under the Auspices of EBMT. 2017. https://10.1007/978-3-319-50026-3_2.

- 3. Granot N, Storb R. History of hematopoietic cell transplantation: challenges and progress. Haematologica 2020;105:2716–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spierings E, Fleischhauer K Histocompatibility. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N (eds). The EBMT Handbook, 61–8 ( Springer International Publishing, 2019). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02278-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ayuk F, Balduzzi A. Donor Selection for Adults and Pediatrics. The EBMT Handbook (Springer International Publishing, 2019). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Landry I. Racial disparities in hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a systematic review of the literature. Stem Cell Investig 2021;8:24–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Canarutto D, Tucci F, Gattillo S, et al. Peripheral blood stem and progenitor cell collection in pediatric candidates for ex vivo gene therapy: a 10-year series. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021;22:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heimfeld S. Bone marrow transplantation: how important is CD34 cell dose in HLA-identical stem cell transplantation? Leukemia 2003;17:856–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Panch SR, Szymanski J, Savani BN, et al. Sources of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and methods to optimize yields for clinical cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017;23:1241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Menendez-Gonzalez JB, Hoggatt J. Hematopoietic stem cell mobilization: current collection approaches, stem cell heterogeneity, and a proposed new method for stem cell transplant conditioning. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021;17:1939–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonig H, Papayannopoulou T. Hematopoietic stem cell mobilization: updated conceptual renditions. Leukemia 2013;27:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Metcalf D. The colony stimulating factors discovery, development, and clinical applications. Cancer 1990. 10.1002/1097-0142(19900515)65:102185::AID-CNCR28206510053.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McQuibban GA, Gong JH, Tam EM, et al. Inflammation dampened by gelatinase a cleavage of monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Science 2000;289:1202–6. 10.1126/science.289.5482.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lévesque JP, Takamatsu Y, Nilsson SK, et al. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD106) is cleaved by neutrophil proteases in the bone marrow following hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood 2001. 10.1182/blood.V98.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, Liu F, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood 2005;106:3020–7. 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hübel K Mobilization and collection of HSC. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mothy M, Kröger N (eds). The EBMT Handbook, 117–22 ( Springer International Publishing, 2019). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02278-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devine SM, Vij R, Rettig M, et al. Rapid mobilization of functional donor hematopoietic cells without G-CSF using AMD3100, an antagonist of the CXCR4/SDF-1 interaction. Blood 2008;112:990–8. 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Clercq E. Mozobil® (Plerixafor, AMD3100), 10 years after its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration. Antivir Chem Chemother 2019;27:204020661982938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lidonnici MR, Aprile A, Frittoli MC, et al. Plerixafor and G-CSF combination mobilizes hematopoietic stem and progenitors cells with a distinct transcriptional profile and a reduced in vivo homing capacity compared to plerixafor alone. Haematologica 2017;102:e120–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Teipel R, Oelschlägel U, Wetzko K, et al. Differences in cellular composition of peripheral blood stem cell grafts from healthy stem cell donors mobilized with either granulocyte Colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) alone or G-CSF and Plerixafor. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018;24:2171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mombled M, Rodriguez L, Avalon M, et al. Characteristics of cells with engraftment capacity within CD34+ cell population upon G-CSF and Plerixafor mobilization. Leukemia 2020;34:3370–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rutella S, Filippini P, Bertaina V, et al. Mobilization of healthy donors with plerixafor affects the cellular composition of T-cell receptor (TCR)-αβ/CD19-depleted haploidentical stem cell grafts. J Transl Med 2014;12:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lundqvist A, Smith AL, Takahashi Y, et al. Differences in the phenotype, cytokine gene expression profiles, and in vivo alloreactivity of T cells mobilized with Plerixafor compared with G-CSF. J Immunol 2013;191:6241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramirez P, Rettig MP, Uy GL, et al. BIO5192, a small molecule inhibitor of VLA-4, mobilizes hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood 2009;114:1340–3. 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rettig MP, Ansstas G, Dipersio JF. Mobilization of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using inhibitors of CXCR4 and VLA-4. Leukemia 2012;26:34–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fukuda S, Bian H, King AG, et al. The chemokine GROβ mobilizes early hematopoietic stem cells characterized by enhanced homing and engraftment. Blood 2007;110:860–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suárez-Álvarez B, López-Vázquez A, López-Larrea C. Mobilization and homing of hematopoietic stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012;741:152–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li C, Georgakopoulou A, Mishra A, et al. In vivo HSPC gene therapy with base editors allows for efficient reactivation of fetal γ-globin in β-YAC mice. Blood Adv 2021;5:1122–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagler A, Shimoni A Conditioning. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N (eds). The EBMT Handbook, 99–107 ( Springer International Publishing, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mikulska M Neutropenic Fever. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N (eds). The EBMT Handbook, 259–64 ( Springer International Publishing, 2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schrezenmeier H, Körper S, Höchsmann B, et al. Transfusion Support. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N (eds.). The EBMT Handbook. Springer International Publishing, 2019,163–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stewart D, Guo D, Luider J, et al. Factors predicting engraftment of autologous blood stem cells: CD34+ subsets inferior to the total CD34+ cell dose. Bone Marrow Transplant 1999;23:1237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciceri F, Bacigalupo A, Lankester A, et al. Haploidentical HSCT. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N (eds.). The EBMT Handbook. Springer International Publishing, 2019,479–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gyurkocza B, Sandmaier BM. Conditioning regimens for hematopoietic cell transplantation: one size does not fit all. Blood 2014;124:344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tucci F, Galimberti S, Naldini L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of gene therapy with hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells for monogenic disorders. Nat Commun 2022;13:1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naldini L. Genetic engineering of hematopoiesis: current stage of clinical translation and future perspectives. EMBO Mol Med 2019;11:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferrari S, Vavassori V, Canarutto D, et al. Gene editing of hematopoietic stem cells: hopes and hurdles toward clinical translation. Front Genome Ed 2021;3:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. N Engl J Med 2021;384:252–60. 10.1056/NEJMoa2031054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ferrari S, Valeri E, Conti A, et al. Genetic engineering meets hematopoietic stem cell biology for next-generation gene therapy. Cell Stem Cell 2023;30:549–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ferrari G, Thrasher AJ, Aiuti A. Gene therapy using haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat Rev Genet 2021;22:216–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hall KM, Horvath TL, Abonour R, et al. Decreased homing of retrovirally transduced human bone marrow CD34+ cells in the NOD/SCID mouse model. Exp Hematol 2006;34:433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schiroli G, Conti A, Ferrari S, et al. Precise gene editing preserves hematopoietic stem cell function following transient p53-mediated DNA damage response. Cell Stem Cell 2019;24:551–565.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van der Loo JC, Ploemacher RE. Marrow- and spleen-seeding efficiencies of all murine hematopoietic stem cell subsets are decreased by preincubation with hematopoietic growth factors. Blood 1995;85:2598–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Hennik PB, de Koning AE, Ploemacher RE. Seeding efficiency of primitive human hematopoietic cells in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immune deficiency mice: implications for stem cell frequency assessment. Blood 1999;94:3055–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Río P, Navarro S, Wang W, et al. Successful engraftment of gene-corrected hematopoietic stem cells in non-conditioned patients with Fanconi anemia. Nat Med 2019;25:1396–401. 10.1038/s41591-019-0550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Micklem HS, Clarke CM, Evans EP, et al. Fate of chromosome-marked mouse bone marrow cells tranfused into normal syngeneic recipients. Transplantation 1968;6:299–302. 10.1097/00007890-196803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rao SS, Peters SO, Crittenden RB, et al. Stem cell transplantation in the normal nonmyeloblasted host: relationship between cell dose, schedule, and engraftment. Exp Hematol 1997;25:114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wilkinson AC, Ishida R, Kikuchi M, et al. Long-term ex vivo haematopoietic-stem-cell expansion allows nonconditioned transplantation. Nature Preprint at 2019;571:117–21. 10.1038/s41586-019-1244-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wagner JE, Brunstein CG, Boitano AE, et al. Phase I/II trial of StemRegenin-1 expanded umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells supports testing as a stand-alone graft. Cell Stem Cell 2016;18:144–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sakurai M, Ishitsuka K, Ito R, et al. Chemically defined cytokine-free expansion of human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2023;615:127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stewart F, Zhong S, Wuu J, et al. Lymphohematopoietic engraftment in minimally myeloablated hosts. Blood 1998;91:3681–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rao S, Peters SO, Crittenden RB, et al. Stem cell transplantation in the normal nonmyeloablated host: relationship between cell dose, schedule, and engraftment. Exp Hematol 1997;25:114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peci F, Dekker L, Pagliaro A, et al. The cellular composition and function of the bone marrow niche after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2022;57:1357–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Migliaccio AR. “To condition” or not “to condition”, this is the question. Exp Hematol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cosgun KN, Rahmig S, Mende N, et al. Kit regulates HSC engraftment across the human-mouse species barrier. Cell Stem Cell 2014;15:227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Waskow C, Madan V, Bartels S, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without irradiation. Nat Methods 2009;6:267–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kahn J, Byk T, Jansson-Sjostrand L, et al. Overexpression of CXCR4 on human CD34+ progenitors increases their proliferation, migration, and NOD/SCID repopulation. Blood 2004;103:2942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mankad A, Taniguchi T, Cox B, et al. Natural gene therapy in monozygotic twins with Fanconi anemia. Blood 2006;107:3084–90. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schiroli G, Ferrari S, Conway A, et al. Preclinical modeling highlights the therapeutic potential of hematopoietic stem cell gene editing for correction of SCID-X1. Sci Transl Med 2017;9:eaan0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Griffin JM, Healy FM, Dahal LN, et al. Worked to the bone: antibody-based conditioning as the future of transplant biology. J Hematol Oncol 2022;15:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Palchaudhuri R, Saez B, Hoggatt J, et al. Non-genotoxic conditioning for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using a hematopoietic-cell-specific internalizing immunotoxin. Nat Biotechnol 2016;34:738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Czechowicz A, Kraft D, Weissman IL, et al. Efficient transplantation via antibody-based clearance of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Science 2007;318:1296–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kwon HS, Logan AC, Chhabra A, et al. Anti-human CD117 antibody-mediated bone marrow niche clearance in nonhuman primates and humanized NSG mice. Blood 2019;133:2104–8. 10.1182/blood-2018-06-853879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Czechowicz A, Palchaudhuri R, Scheck A, et al. Selective hematopoietic stem cell ablation using CD117-antibody-drug-conjugates enables safe and effective transplantation with immunity preservation. Nat Commun 2019;10:617. 10.1038/s41467-018-08201-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Omer-Javed A, Pedrazzani G, Albano L, et al. Mobilization-based chemotherapy-free engraftment of gene-edited human hematopoietic stem cells. Cell 2022;185:2248–64.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chen J, Larochelle Á, Fricker S, et al. Mobilization as a preparative regimen for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2006;107:3764–71. 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chen C, Guderyon MJ, Li Y, et al. Non-toxic HSC transplantation-based macrophage/microglia-mediated GDNF delivery for Parkinson’s disease. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020;17:83–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Guderyon MJ, Chen C, Bhattacharjee A, et al. Mobilization-based transplantation of young-donor hematopoietic stem cells extends lifespan in mice. Aging Cell 2020;19:e13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vavassori V, Mercuri E, Marcovecchio GE, et al. Modeling, optimization, and comparable efficacy of T cell and hematopoietic stem cell gene editing for treating hyper-IgM syndrome. EMBO Mol Med 2021;13:e13545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schmidt AH, Mengling T, Hernández-Frederick CJ, et al. Retrospective analysis of 37,287 observation years after peripheral blood stem cell donation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017;23:1011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rüesch M, Amar el Dusouqui S, Buhrfeind E, et al. Basic characteristics and safety of donation in related and unrelated haematopoietic progenitor cell donors – first 10 years of prospective donor follow-up of Swiss donors. Bone Marrow Transplant 2022;57:918–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang H, Germond A, Li C, et al. In vivo HSC transduction in rhesus macaques with an HDAd5/3 + vector targeting desmoglein 2 and transiently overexpressing cxcr4. Blood Adv 2022;6:4360–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Inamoto Y, Lee SJ. Late effects of blood and marrow transplantation. Haematologica 2017;102:614–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Grupp SA, Corbacioglu S, Kang HJ, et al. Defibrotide plus best standard of care compared with best standard of care alone for the prevention of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HARMONY): a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 2023;10:e333–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Laberko A, Gennery AR. Cytoreductive conditioning for severe combined immunodeficiency – help or hindrance? Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2015;11:785–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Dufour C. How I manage patients with Fanconi anaemia. Br J Haematol 2017;178:32–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Birocchi F, Cusimano M, Rossari F, et al. Targeted inducible delivery of immunoactivating cytokines reprograms glioblastoma microenvironment and inhibits growth in mouse models. Sci Transl Med 2022;14:eabl4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mucci A, Antonarelli G, Caserta C, et al. Myeloid cell-based delivery of IFN-γ reprograms the leukemia microenvironment and induces anti-tumoral immune responses. EMBO Mol Med 2021;13:e13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Konopleva M, Benton CB, Thall PF, et al. Leukemia cell mobilization with G-CSF plus plerixafor during busulfan-fludarabine conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015;50:939–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dvorak CC, Horn BN, Puck JM, et al. A trial of plerixafor adjunctive therapy in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with minimal conditioning for severe combined immunodeficiency. Pediatr Transplant 2014;18:602–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang H, Georgakopoulou A, Psatha N, et al. In vivo hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy ameliorates murine thalassemia intermedia. J Clin Invest 2019;129:598–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li C, Georgakopoulou A, Gil S, et al. In vivo HSC gene therapy with base editors allows for efficient reactivation of Fetal globin in Beta-Yac mice. Blood 2020;136:22–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Richter M, Saydaminova K, Yumul R, et al. In vivo transduction of primitive mobilized hematopoietic stem cells after intravenous injection of integrating adenovirus vectors. Blood 2016;128:2206–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this review.