Abstract

Breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Moreover, standard treatments are limited, so new alternative treatments are required. Thai traditional formulary medicine (TTFM) utilizes certain herbs to treat different diseases due to their dominant properties including anti-fungal, anti-bacterial, antigenotoxic, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer actions. However, very little is known about the anti-cancer properties of TTFM against breast cancer cells and the underlying molecular mechanism has not been elucidated. Therefore, the present study, evaluated the metabolite profiles of TTFM extracts, the anti-cancer activities of TTFM extracts, their effects on the apoptosis pathway and associated gene expression profiles. Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy analysis identified a total of 226 compounds within the TTFM extracts. Several of these compounds have been previously shown to have an anti-cancer effect in certain cancer types. The MTT results demonstrated that the TTFM extracts significantly reduced the cell viability of the breast cancer 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Moreover, an apoptosis assay, demonstrated that the TTFM extracts significantly increased the proportion of apoptotic cells. Furthermore, the RNA-sequencing results demonstrated that 25 known genes were affected by TTFM treatment in 4T1 cells. TTFM treatment significantly up-regulated Slc5a8 and Arhgap9 expression compared with untreated cells. Moreover, Cybb, and Bach2os were significantly downregulated after TTFM treatment compared with untreated cells. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR demonstrated that TTFM extract treatment significantly increased Slc5a8 and Arhgap9 mRNA expression levels and significantly decreased Cybb mRNA expression levels. Moreover, the mRNA expression levels of Bax and Casp9 were significantly increased after TTFM treatment in 4T1 cells compared with EpH4-Ev cells. These findings indicated anti-breast cancer activity via induction of the apoptotic process. However, further experiments are required to elucidate how TTFM specifically regulates genes and proteins. This study supports the potential usage of TTFM extracts for the development of anti-cancer drugs.

Keywords: anti-cancer, apoptosis, breast cancer, traditional medicine, transcriptome, gene expression

Introduction

A major public health issue and one of the leading causes of death worldwide is breast cancer (BC). BC is the third most prevalent malignancy in Thailand, and its occurrence is steadily rising (1,2). The World Health Organization has reported that >20,000 new cases of BC (11.6% of all cases) were reported in Thailand in 2020(3). There are currently only a few standard treatments available for breast cancer because of the negative side-effects, high cost and cancer development associated with current treatments. New complementary therapies are therefore required and one option that has drawn interest from cancer patients is treatment with Thai traditional formulary medicine (TTFM) or a combination of contemporary medicine and specific natural items, such as herbs (4-6).

TTFMs are a valuable legacy of Thai ancestral knowledge. Numerous herbs used in TTFM recipes have been previously reported to have anti-fungal, anti-bacterial, anti-genotoxic, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties (7-9). Over hundreds of years, different TTFM recipes have been successfully utilized to treat symptoms related to breast and intestinal problems. The TTFM recipe used in the present study was taken from the TTFM, Atisaravak scripture and included seventeen dried herbs (Table I).

Table I.

The portion of the herb used and the amount of each ingredient in the Thai traditional formulary medicine formulation.

| Scientific name | Common name | Part used | Ratio (%) | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligusticum sinense Oliv.cv. Chaxiong | Sichuan lovage | Rhizome | 4.76 | (10,11) |

| Angelica dahurica | Chinese angelica | Root | 4.76 | (12) |

| Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC | Cang Zhu | Rhizome | 4.76 | (13) |

| Artemisia annua L | Sweet wormwood | Leaf and flower | 4.76 | (14) |

| Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels | Danggui | Root | 4.76 | N/A |

| Lepidium sativum L | Garden cress | Seed | 4.76 | (15) |

| Nigella sativa L | Black cumin | Seed | 4.76 | (16,17) |

| Cuminum cyminum L | Cumin | Fruit | 4.76 | (17) |

| Foeniculum vulgare Miller | Fennel | Fruit | 4.76 | N/A |

| Anethum graveolens L | Dill | Fruit | 4.76 | (18) |

| Amomum villosum Lour | Bastard cardamom | Seed | 4.76 | (19) |

| Amomum kravanh | Cambodian cardamom | Fruit | 4.76 | (20) |

| Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry | Cloves | Flower | 4.76 | (21) |

| Caesalpinia sappan L | Sappan Wood | Wood | 9.52 | (22) |

| Maclura cochinchinensis (Lour.) Corner | Cockspur thorn | Wood | 9.52 | N/A |

| Curcuma zedoaria | Zedoary | Rhizome | 9.52 | (23) |

| Punica granatum L | Pomegranate | Peel | 9.52 | (24,25) |

N/A, no reference identified.

Moreover, consuming a diet rich in micronutrients such as fiber, minerals, vitamins and phytonutrients has been reported to reduce the risk of BC and to demonstrated preventative anti-cancer activity (26). Many phytochemical compounds including phenolic compounds (such as, coumarins, flavonoids, lignans, phenolic acids, quinones, stilbenes and tannins), nitrogen compounds (such as alkaloids, amines and betalains), vitamins (such as A, C, D and E) and terpenes (including carotenoids) derived from certain herbs in the TTFM recipe have been reported to have the cytotoxic effects against certain cancer cells, such as non-small cell lung cancer (13,14), cervical cancer (27), colon cancer (28), gastric cancer (29), leukemic cancer (15,24) and breast cancer (22,23,25). Furthermore, a previous in vitro study reported that a variety of phytochemical substances plays a crucial part in inflammation in breast cancer (30).

The mixture of TTFM recipe in this combination may balance the effects of each phytochemical, lessen any adverse effects and increase the efficacy of the treatment because each herb, according to TTFM, possesses a range of medicinal characteristics. However, no research has either proven the efficacy of the TTFM formula against breast cancer cells or has elucidated the underlying molecular mechanisms (31).

Therefore, the present study assessed the secondary metabolites (phytochemical profile) of the TTFM extracts and their effects against cancer cells as well as biological properties, such as their effects on programmed cell death and the effect of whole RNA expression upon treatment in breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Preparation of TTFM extraction

The dried plant materials (Table I) were purchased from a Thai traditional medicine shop (Chao-Krom-Poe Dispensary Pharmacy). The mixed plant materials were boiled in 3.15 l of water for 30 min. After passing through the sterile voile fabric, the sample was centrifuged at 1,610 x g at 4˚C for 20 min. The pellet was discarded, while the supernatants were lyophilized and then kept at -20˚C until use.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fractionation

HPLC fractionation was performed before liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS) analysis. Briefly, 20 µg of dried TTFM extracts were incubated in 90% methanol at 25˚C and shaken at 1,300 rpm for 20 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 17,000 x g at 4˚C for 10 min, the supernatants were then collected and transferred to an HPLC vial (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Fractionations were performed using reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) on an Agilent 1200 HPLC device coupled with a 1260 Infinity II with a UV detector (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The solvents used for HPLC fractionation were ultrapure water (type I water) subjected to purification with a MilliQ system (Merck KGaA) to obtain an electrical resistance of 18.2 MW as solvent A and acetonitrile of HPLC grade (RCI Labscan, Ltd.) as solvent B. The column stationary phase was graphitic porous carbon (Hypercarb; 100x2.1 mm; particle size, 3 µm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with a controlled temperature of 65±0.8˚C. The mobile phases with a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min were programmed as follows: 0-5 min, isocratic elution of 5% B; 5-40 min, gradient elution of 2.28% B/min; 40-50 min, isocratic elution of 100% B (column wash); 50-65 min, isocratic elution of 5% B (recondition of the HPLC column); four fractions (2 ml each) were collected for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-MS/MS (UHPLC-MS/MS) characterization

Data dependent analysis was used for untargeted metabolomics measurements, which were performed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC coupled with an Orbitrap Q exactive focus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The heated electrospray ionisation source parameters were set as follows: Sheath gas flow rate of 30 arbitrary unit; aux gas flow of 10 l/min; spray voltage of 3 kV; capillary temperature of 350˚C; S-lens RF level of 60; auxiliary gas heater temperature of 300˚C. Separation of polar metabolites was performed using an Acclaim™ Polar Advantage II (250x3 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) set to a 3 µm particle size. The mobile phases were prepared according to the aforementioned method. The settings for the LC gradient were 0-5 min, isocratic elution of 1% B; 5-40 min, gradient elution of 1.5% B/min; 40-47 min, isocratic elution of 100% B (column wash); 47-65 min, isocratic elution of 1% B (recondition of the HPLC column).

Differential peak identification was performed using MS-Dial software (version 4.90) (32). Raw files were converted into Analysis Base Framework (ABF) format using an ABF file converter (http://www.reifycs.com/AbfConverter/index.html). In MS-DIAL, the converted files were processed with default parameters for deconvolution, peak picking, alignment and compound identification based on public MSP-formatted libraries (MSPs) for both positive and negative ionization modes (http://prime.psc.riken.jp/compms/msdial/main.html#MSP). The MS/MS analytical conditions (scan range, 70-1035 m/z) comprised a minimum peak height of 1,000 amplitude, m/z search tolerance of 0.01 Da, data acquisition with centroid mode and the filter of peak alignment before removal of features based on blank information.

Cell culture

The mouse 4T1 cell line [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) CRL-2539™], which mimics stage IV human breast cancer, were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 4,500 mg/l glucose (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1,500 mg/l sodium bicarbonate (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell line (gift from The Ketchart Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University) was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The study also included the normal EpH4-Ev breast cell line (ATCC CRL-30639™), as the control, which was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% Calf Bovine Serum (ATCC), 1.2 µg/ml puromycin dihydrochloride (Merck KGaA) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All cells were maintained under 5% CO2 at 37˚C.

Cell viability assay

An MTT test was used to perform a cell viability assay. Briefly, each of the cell lines were seeded (1x104) in 96 well-microplates and incubated under 5% CO2 at 37˚C for 24 h. Then, cells were exposed to TTFM extracts (final concentrations, 0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 200 and 400 µg/ml). After adding extracts, cells were incubated for 5 days without changing the medium or substituting the TTFM extracts. After incubation, treated cells were assessed with 0.4 mg/m of the membrane-permeable MTT dye (Abcam) for 3 h. The water-insoluble formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO (Merck KGaA) and the absorbance (570 nm) was quantified using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Apoptosis assay

4T1 cells were seeded (1x105) in 24 well-microplates and incubated under 5% CO2 at 37˚C for 24 h. Cells were then treated with TTFM extracts and incubated at 37˚C for 72 h. The cells were then harvested and washed twice with cold PBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells were stained using a FITC Annexin V Apoptosis detection kit with propidium iodide (Biolegend, Inc.) in the dark at 25˚C for 15 min. Finally, the fluorescent intensity of stained cells was evaluated using a BD™ LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva™ Software v. 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences).

RNA preparation and sequencing (RNA-seq)

Total RNA was extracted from TTFM-treated 4T1 cells, TTFM-treated EpH4-Ev cells, and untreated cells using a RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Inc.). The concentration and RNA integrity were assessed using a Qubit RNA assay kit and Qubit RNA IQ assay kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A Bioanalyzer® (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used to verify the quality and the integrity of processed samples. The library preparation and RNA sequencing were performed commercially by Vishuo Biomedical Pte., Ltd. according to the manufacturer's standard protocols. The library preparation was performed using a NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (Illumina, Inc.). Briefly, 1 g of total RNA was utilized. Oligo(dT) beads were used to isolate poly(A) mRNA. High temperature (94˚C) and divalent cations were used to fragment the mRNA. Random primers from the Library Prep Kit were used for cDNA synthesis. For first strand cDNA synthesis, 25˚C (10 min), 42˚C (15 min), and 70˚C (15 min) were used, followed by second strand cDNA synthesis at 16˚C (1 h). T-A ligation was then used to add adaptors to both ends of the purified double-stranded cDNA, which had previously been treated to repair both ends and add a dA-tail in a single reaction. Then, DNA clean beads were used for size-selection (>200 nt) of the adaptor-ligated DNA. Each library was verified using an Bioanalyzer® Agilent High Sensitivity Chip (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and quantified using KAPA Library Quantification Kits (Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd). Subsequently, libraries with various indexes were multiplexed (3 nM final concentration) and loaded onto a NovaSeq 6000 instrument (Illumina, Inc.) with NovaSeq 6000 SP Reagent Kit v1.5 (300 cycles; Illumina, Inc.) for paired-end (2x150) sequencing according to the manufacturer's protocols.

RNA-seq data analysis

For the analysis of differentially expressed genes, the RNA-seq data were processed as previously reported (33). The trimmed reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (GRCm39/mm10) using HISAT2 v.2.1.0(34) with default parameters. The prevalence of transcripts was quantified using Cufflinks v.2.2.1(35). Differentially expressed genes were then investigated using DESeq2 (version 1.24.0) (36) with an adjusted cut-off of P<0.05. The gene ontology and relevant biological pathways were identified using GOSeq (v1.34.1) (37) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (38), respectively.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from TTFM-treated 4T1 cells, TTFM-treated EpH4-Ev cells, and untreated cells according to the aforementioned method. Reverse transcription was performed by mixing the total RNA with oligo(dT) primers and incubated at 65˚C for 5 min. After that the component was mixed with 4 µl of 5x reaction buffer for RT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 0.5 µl of 40 U/µl Ribolock RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1 µl of 200 U/µl RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 2 µl of 10 mM dNTP mix (Promega) at 42˚C for 1 h. Next, the RT-qPCR assay was performed using the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Amplifications were performed in 10 µl reaction solutions containing 5 µl of 2x PanGreen™ Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Helix Co., Ltd.), 0.25 µl each of 10 µM gene-specific primers, 3.5 µM of nuclease-free water and 1 µl of cDNA. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95˚C for 2 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 15 s, 60˚C for 20 s and 75˚C for 30 s. The specificity of each pair of primers was evaluated using melting curve analysis (95˚C for 15 s, 60˚C for 1 min and 95˚C for 15 s). The experiment was performed with technical triplicates. The relative expression of target genes normalized with Actb was determined using the 2-ΔΔCq method (39). The primers for Slc5a8, Arhgap9, and Cybb were designed in the present study, whereas the primers for Actb, Bcl2, Bax, Casp8, and Casp9 were used according to previous studies (40-43). The gene-specific primers used are presented in Table SI.

Statistical analysis

The apoptosis assay was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. The cell viability and quantification of mRNA expression were assessed using the unpaired t-test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.0 (Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Metabolite profiles of TTFM extracts

The LC-MS/MS data were processed and evaluated using MS-Dial software to identify the TTFM extract profiles. Based on the combined information from accurate mass, isotope ratios, retention-time prediction and MS/MS fragment matching, a total of 226 compounds were identified in the TTFM extract. A total of 64 compounds were identified in the negative ion mode (Table SII) and 162 compounds were identified in the positive ion mode (Table SIII). Several of the metabolites identified have been previously reported to have anti-cancer properties, including betaine, costunolide, cyanidin, d-limonene, geranic acid, ginkgolide A, hinokitiol, l-arginine, oleic acid, parecoxib, pentadecanoic acid, sinapic acid, syringic acid, tanshinone I, tryptanthrin and vinpocetine (Table II).

Table II.

Compounds extracted from Thai traditional formulary medicine reported to exert anti-cancer properties.

| Compound name | Pathway | Cancer type | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | Suppression of the colon tumor formation by inhibition of NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS and COX-2 | Colitis-associated colon cancer | (55) |

| Costunolide | Elevation of the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax while lowering the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, including Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL | Skin cancer and Melanoma | (44,45) |

| Suppression of melanoma cell growth via the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway | |||

| Cyanidin | Activation of apoptosis by caspase-3 cleavage and DNA fragmentation through the Bcl-2 and Bax signaling pathway | Breast cancer | (46,47) |

| Down-regulation of Sirt1 expression via inhibition of mRNA translation | |||

| D-limonene | Suppression of lung cancer growth and induction of apoptosis via a mechanism involving autophagy | Lung cancer | (60) |

| Geranic acid | Induction of apoptosis by induction of the activity of the caspase-3 protein | Colon cancer | (61) |

| Ginkgolide A | Inhibitory effect appeared to be cell cycle blockage at G0/G1 to S phase | Ovarian cancer | (56) |

| Hinokitiol | Increased reactive oxygen species level and activated apoptosis and autophagy through the ERK1/2 signaling pathway | Endometrial cancer and breast cancer | (48,49) |

| Inhibition of heparanase via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase B signaling pathway | |||

| L-arginine | Enhancement of anti-tumor effects in breast cancer mice by improving the immune status | Breast cancer | (62) |

| Increased the proliferation of CD8+ and CD4+ Th1 effector T cells and IFN-γ, as well as decreased frequency of myeloid-derived suppressor cells | |||

| Oleic acid | Decreased IFN-γ-induced expression of PD-L1, Bax, Bcl-2 and caspase 3 Inhibition of PD-1 expression and induction of apoptosis via STAT phosphorylation | Lung cancer | (50) |

| Parecoxib | Inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis by downregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | Colon cancer | (57) |

| Pentadecanoic acid | Increased the expression of cleaved caspase-3, -7, -8 and -9, which are involved in the induction of apoptosis | Breast cancer | (51) |

| Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway | |||

| Sinapic acid | Downregulation of the AKT/Gsk-3β signal pathway | Pancreatic cancer | (58) |

| Syringic acid | Induction of apoptosis, inhibition of inflammation and the suppression of the mTOR/AKT signaling pathway | Gastric cancer | (52) |

| Tanshinone I | Induction of apoptosis by activation of the expression of caspase 3, downregulation of the level of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2, and upregulation of the level of the pro-apoptotic protein, Bax | Breast cancer | (53) |

| Tryptanthrin | Suppression of the expression of NOS1, COX-2 and NF-κB in mouse tumor tissues, and regulation of IL-2, IL-10 and TNF-α | Breast cancer | (59) |

| Exertion of anti-cancer activities via modulation of the inflammatory epithelial-mesenchymal transition | |||

| Vinpocetine | Activation of Akt and STAT3 but had no effects on MAPK signaling pathways | Breast cancer | (54) |

Effects of TTFM extracts on breast cancer cells

The 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and the EpH4-Ev normal breast cells were treated with TTFM (0-400 µg/ml) for 5 days. TTFM extracts significantly decreased the viability of 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner; however, no significant affect was demonstrated for the EpH4-Ev cells (Fig. 1A-C). The IC50 values for TTFM extracts against 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells were 3.05 and 71.34 µg/ml, respectively (Fig. 1D). An IC50 value for EpH4-Ev was not determined.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effect of TTFM on the proliferation of 4T1, MDA-MB-231 and EpH4-Ev cells. (A-C) Cell viability assay and (D) IC50 proliferation of 4T1, MDA-MB-231 and EpH4-Ev cells after 5 days of treatment with TTFM. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. TTFM, Thai traditional formulary medicine.

Effects of TTFM extracts on the apoptotic process

To ensure that there was a sufficient cell population for use in the apoptotic assay, 4T1 cells were treated with 0-400 µg/ml of TTFM extracts and incubated for 3 days rather than 5 days. The mock (negative control) analysis demonstrated that ~86% of the 4T1 cells were alive, with the rest appearing as late apoptotic cells (8%), early apoptotic cells (5%) and dead cells (1%) (Fig. 2A and H). The proportion of early and late apoptotic cells increased by 2.7 and 8.5-fold, respectively, after the addition of the apoptotic inducer (positive control; 1 mM H2O2) compared with the mock group. The apoptotic inducer significantly enhanced the proportion of early and late apoptotic cells (Fig. 2B and H); however, the lower TTFM extract concentrations (25 and 50 µg/ml) only slightly raised the numbers of late apoptotic cells by about 1 and 1.2-fold when compared with the mock (Fig. 2C, D and H). When the treatment concentration was raised to 200 and 400 µg/ml, the proportion of late apoptotic cells significantly increased by 1.5 and 2.7-fold, respectively. Furthermore, the proportion of early apoptotic cells significantly increased by 6.9 and 2.7-fold, respectively (Fig. 2F-H). Subsequently, studies were performed to evaluate how TTFM extracts affected the gene expression profiles of the cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of TTFM on the apoptosis of 4T1 cells. Cell apoptosis data were analyzed for each group after 72 h treatment with TTFM at (A) 0 µg/ml, (C) 25 µg/ml, (D) 50 µg/ml, (E) 100 µg/ml, (F) 200 µg/ml and (G) 400 µg/ml. (B) Positive control cells were induced using 1 mM H2O2. (H) Quantitative analysis of the apoptosis rates among groups (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. mock.

Effects of TTFM extracts on breast cancer cell pathways and entire mRNA transcripts

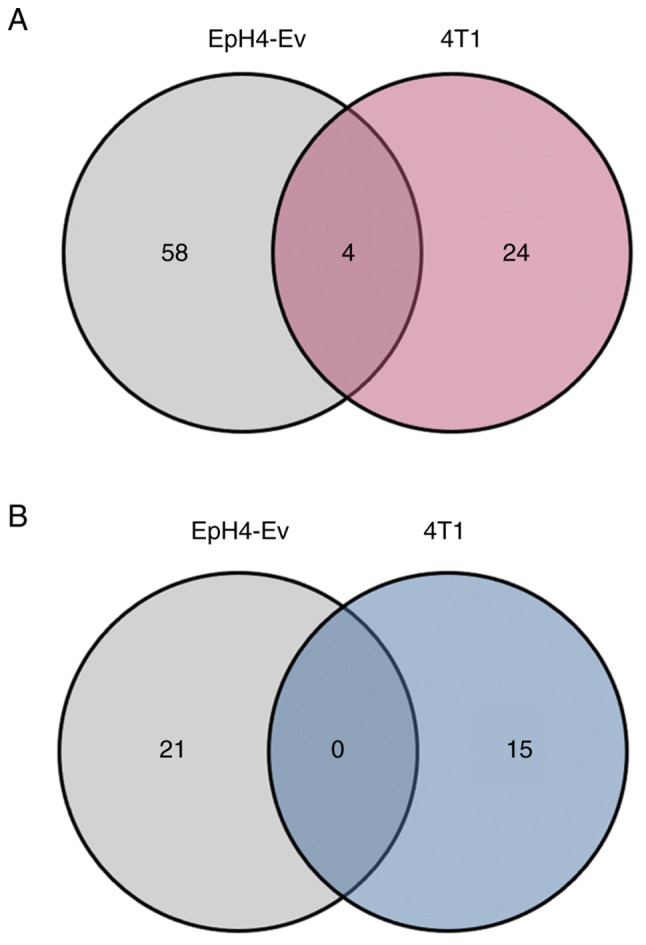

To further evaluate the effect of TTFM on gene expression in breast cancer cells, RNA-seq analysis was performed. Briefly, cells were exposed to TTFM extracts for 72 h at a final concentration of 25 µg/ml and the total RNA was collected in triplicate. A total of 55,359 protein-coding and non-protein coding genes were identified in both EpH4-Ev and 4T1 cells, respectively. TTFM treatment resulted in 62 and 28 genes whose expression was raised in EpH4-Ev and 4T1 cells, respectively, and 21 and 15 genes, respectively, whose expression was decreased more than twofold with statistical significance (|log2fold-change|>1, P<0.05) compared with the corresponding untreated control (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Impact of TTFM on RNA expression in TTFM-treated cells. Venn diagram of the impact of TTFM on RNA expression in TTFM-treated EpH4-Ev and 4T1 cells compared with their respective, untreated cells. (A) Up-regulated genes and (B) down-regulated genes.

TTFM regulated the mRNA expression levels of 25 known genes in 4T1 breast cancer cells (Fig. 4 and Table SIV). Following treatment with TTFM extracts, the mRNA expression levels of Acta1, Tnnc2, 0610039K10Rik, Flacc1, Arl5c, Slc5a8, Krt20, BC147527, Raet1e, Snord72, Acat3, Otop1, Arhgap9, Eef1a2, Hmgb1-ps7, Ndufb4c and Ccl20 were significantly increased. Conversely, the mRNA expression levels of Ccdc39, Rbm6-ps1, Grin3b, SNORA21B, Cybb, B430219N15Rik, C1ql4 and Bach2os were significantly decreased after TTFM treatment. Among those genes, TTFM treatment significantly increased the expression of Slc5a8 and Rho Arhgap9, compared with untreated cells. Adversely, compared to the untreated control group, the TTFM treatment markedly decreased the expression of Cybb and Bach2os (Fig. 4 and Table SIV), which had previously been reported to be involved in cell death. Notably, these significantly differently expressed genes, were categorized into six major biological processes based on KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (Table SV): organismal systems (7 genes), metabolism (2 genes), human diseases (9 genes), environmental information processing (5 genes), cellular process (1 genes) and genetic information processing (1 gene).

Figure 4.

Significantly up- and down-regulated genes in TTFM-treated cells. Volcano plot of the significantly up- and down-regulated genes in TTFM-treated 4T1 cells compared with untreated 4T1 cells. DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

TTFM extracts have different effects on Slc5a8, Arhgap9, Cybb and apoptosis-related gene expression in normal breast and breast cancer cell lines

To validate the effects of TTFM on mRNA transcripts, RT-qPCR was performed. In brief, cells were treated with TTFM extracts for 72 h at a final concentration of 25 µg/ml, and the total RNA was collected in triplicate, followed by cDNA synthesis. The results demonstrated that TTFM treatment significantly enhanced the mRNA expression levels of Slc5a8 and Arhgap9 genes, and significantly reduced the mRNA expression levels of Cybb in TTFM-treated 4T1 cells compared with TTFM-treated EpH4-Ev cells (Fig. 5A-C). Moreover, TTFM treatment significantly increased the mRNA expression levels of Bax and Casp9 in TTFM-treated 4T1 cells compared with TTFM-treated EpH4-Ev cells (Fig. 5D-G).

Figure 5.

mRNA expression levels TTFM-treated cells. Relative mRNA expression levels of (A) Slc5a8, (B) Arhgap9, (C) Cybb and (D-G) apoptosis-related genes in treated cells compared with untreated cells. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. EpH4-Ev, treated EpH4-Ev cells-untreated EpH4-Ev cells; 4T1, treated 4T1cells-untreated 4T1 cells.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported that numerous plant extracts have cytotoxic effects against cancer cells (7,30). The present study evaluated the effects of TTFM extracts on breast cancer cell viability using the MTT assay. The results suggested that TTFM extracts possessed anti-breast cancer activity. These findings demonstrated that the TTFM extracts had different effects on cancer cells and normal cells, which could lead to more severe cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells.

LC-MS/MS analysis demonstrated that TTFM extracts included numerous secondary metabolites. Some of which have been previously reported to have anti-cancer properties, including costunolide (44,45), cyanidin (46,47), hinokitiol (48,49), oleic acid (50), pentadecanoic acid (51), syringic acid (52), tanshinone I (53) and vinpocetine (54), which have been reported to inhibit cancer cell growth and proliferation via the induction of apoptosis. The results of the present study were consistent with reports from previous studies that certain metabolites found in medicinal plants might promote apoptosis in breast cancer, possibly reducing the viability of breast cancer cells (46,51,53). The compounds betaine (55), ginkgolide A (56), parecoxib (57), sinapic acid (58) and tryptanthrin (59). which have been previously reported to induce cancer cell death by inhibiting cell proliferation and migration in certain types of cancer, such as colon cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer and breast cancer through different pathways were also found in TTFM extracts. Furthermore, certain metabolites such as d-limonene (60), geranic acid (61), l-arginine (62) and pentadecanoic acid (51) have been previously reported to have demonstrated synergistic effects, enhancing anti-cancer properties of drugs and compounds. It could be hypothesized that the synergistic effects from mixtures of several metabolites are crucial for the anti-breast cancer activity of TTFM extracts. However, the present study lacks data to support the specific mechanism of action for specific components in the TTFM extract, which is a limitation of the present study.

In cancer cells, increased or decreased expression of certain transcripts has been reported to promote cancer cell growth. Previous studies reported that the expression of Slc5a8, a putative tumor suppressor, was repressed in certain cancers, including breast cancer, through DNA methylation (63). Up-regulation of Slc5a8 in cancer cells has been reported to induce apoptosis when its substrates, which are HDAC inhibitors, are present (63). The RNA-seq results of the present study demonstrated that the expression of Slc5a8 was increased following treatment with TTFM extracts. These findings were consistent with a previous study that reported that up-regulation of Slc5a8 in the breast cancer MB231 cell line prevented cells from forming colonies in vitro and tumors in vivo (64).

Furthermore, previous studies reported that the MAPK signaling pathway was regulated by Arhgap9 in breast cancer (65). High levels of Arhgap9 expression inhibited activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, which prevented cell proliferation, invasion and migration (66). The present study demonstrated that TTFM extracts treatment also increased Arhgap9 mRNA expression levels.

Previous studies reported that Cybb was involved in the immune regulation of tumor metastasis and that the expression level of Cybb was higher in triple-negative breast cancer compared with normal tissue (67). In the present study, Cybb mRNA expression levels were significantly suppressed by TTFM treatment. Bach2os are oncogenic lncRNAs that might act as drivers of tumor progression (68). In the present study, following TTFM extract treatment, Bach2os was down regulated in the RNA-seq data.

TTFM treatment significantly enhanced Bax and Casp9 mRNA expression levels in TTFM-treated 4T1 cells compared with TTFM-treated EpH4-Ev cells. A previous study reported that increasing the expression of Bax and Caspase-9, two key regulators of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, was necessary for the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells (51,53,69). When apoptotic stimuli are present, BAX translocate from the cytosol to mitochondria, resulting in dimerization, integration and cytochrome c release, which results in caspase-9 activation and apoptosis (69). Taken together, the results demonstrated that TTFM may have caused breast cancer cells to become cytotoxic by inducing apoptosis. However, the pathways need to be further elucidated and evaluated to support this.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the anti-breast cancer activity of TTFM water extracts. The levels of certain transcripts were altered by TTFM, and this process most likely caused cell death by inducing apoptosis. However, further experiments are required to evaluate how the TTFM extracts used specifically regulate genes and proteins. The TTFM extracts used in the present study are suggested as a potential for further development of anti-breast cancer therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Assoc. Professor Dr Wannarasmi Ketchart (Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand) who kindly provided the MDA-MB-231 cells.

Funding Statement

Funding: The present study was supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund (grant no. CU_FRB640001_01_30_4) and the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund (RA-MF-69/64; Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University). The study was supported by the 100th Anniversary Chulalongkorn University Fund for Doctoral Scholarship.

Availability of data and materials

The RNA-sequencing datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (accession no. SRR18848741-SRR18848746 and SRR18848748-SRR18848753). The data are also available through the NCBI GenBank (accession no. PRJNA830310).

All other data used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SP and NT devised the study. KC reviewed the TTFM Atisaravak scripture and selected the TTFM recipe. AK performed the experiments, analyzed the data and interpreted the results. WJ and PKa performed the LC-MS/MS. PKl collected and analyzed the data. PC performed RNA extraction. PS performed data analysis. AK prepared this manuscript. SP and NT oversaw, revised the final manuscript and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thaineua V, Ansusinha T, Auamkul N, Taneepanichskul S, Urairoekkun C, Jongvanich J, Kannawat C, Traisathit P, Chitapanarux I. Impact of regular Breast Self-Examination on breast cancer size, stage, and mortality in Thailand. Breast J. 2020;26:822–824. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Journal. 2020;2021 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim C, Kim B. Anti-Cancer natural products and their bioactive compounds inducing ER stress-mediated apoptosis: A review. Nutrients. 2018;10(1021) doi: 10.3390/nu10081021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Wang Z, Huang Y, O'Barr SA, Wong RA, Yeung S, Chow MS. Ginseng and anticancer drug combination to improve cancer chemotherapy: A critical review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014(168940) doi: 10.1155/2014/168940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demain AL, Vaishnav P. Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:687–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrowder DA, Miller FG, Nwokocha CR, Anderson MS, Wilson-Clarke C, Vaz K, Anderson-Jackson L, Brown J. Medicinal herbs used in traditional management of breast cancer: Mechanisms of action. Medicines (Basel) 2020;7(47) doi: 10.3390/medicines7080047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rayan A, Raiyn J, Falah M. Nature is the best source of anticancer drugs: Indexing natural products for their anticancer bioactivity. PLoS One. 2017;12(e0187925) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdollahzadeh S, Mashouf R, Mortazavi H, Moghaddam M, Roozbahani N, Vahedi M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of punica granatum peel extracts against oral pathogens. J Dent (Tehran) 2011;8:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu PY, Zhong YH, Feng JF, Li DX, Deng P, Zhang WL, Lei ZQ, Liu XM, Zhang GS. Pharmacokinetics of five phthalides in volatile oil of Ligusticum sinense Oliv.cv. Chaxiong, and comparison study on physicochemistry and pharmacokinetics after being formulated into solid dispersion and inclusion compound. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21(129) doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03289-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Q, Yang J, Ren J, Wang A, Ji T, Su Y. Bioactive phthalides from Ligusticum sinense Oliv cv. Chaxiong. Fitoterapia. 2014;93:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu M, Li T, Chen L, Peng S, Liao W, Bai R, Zhao X, Yang H, Wu C, Zeng H, Liu Y. Essential oils from Inula japonica and Angelicae dahuricae enhance sensitivity of MCF-7/ADR breast cancer cells to doxorubicin via multiple mechanisms. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;180:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo W, Liu S, Ju X, Du J, Xu B, Yuan H, Qin F, Li L. The antitumor effect of hinesol, extract from Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. by proliferation, inhibition, and apoptosis induction via MEK/ERK and NF-κB pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines A549 and NCI-H1299. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:18600–18607. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang SJ, Schmiech M, Hafner S, Paetz C, Steinborn C, Huber R, Gaafary ME, Werner K, Schmidt CQ, Syrovets T, Simmet T. Antitumor activity of an Artemisia annua herbal preparation and identification of active ingredients. Phytomedicine. 2019;62(152962) doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basaiyye SS, Kashyap S, Krishnamurthi K, Sivanesan S. Induction of apoptosis in leukemic cells by the alkaloid extract of garden cress (Lepidium sativum L.) J Integr Med. 2019;17:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan MA, Chen HC, Tania M, Zhang DZ. Anticancer activities of Nigella sativa (black cumin) Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2011;8 (5 Suppl):S226–S232. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korff JM, Menke K, Schwermer M, Falke K, Schramm A, Längler A, Zuzak TJ. Antitumoral effects of curcumin (Curcuma longa L.) and thymoquinone (Nigella sativa L.) on neuroblastoma cell lines. Complement Med Res. 2021;28:164–168. doi: 10.1159/000509765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Sheddi ES, Al-Zaid NA, Al-Oqail MM, Al-Massarani SM, El-Gamal AA, Farshori NN. Evaluation of cytotoxicity, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by Anethum graveolens L. essential oil in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Saudi Pharm J. 2019;27:1053–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yue J, Zhang S, Zheng B, Raza F, Luo Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Nie Q, Qiu M. Efficacy and mechanism of active fractions in fruit of amomum villosum lour. for gastric cancer. J Cancer. 2021;12:5991–5998. doi: 10.7150/jca.61310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weerapol Y, Manmuan S, Chaothanaphat N, Okonogi S, Limmatvapirat C, Limmatvapirat S, Tubtimsri S. Impact of fixed oil on ostwald ripening of anti-oral cancer nanoemulsions loaded with amomum kravanh essential oil. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(938) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14050938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dwivedi V, Shrivastava R, Hussain S, Ganguly C, Bharadwaj M. Comparative anticancer potential of clove (Syzygium aromaticum)-an Indian spice-against cancer cell lines of various anatomical origin. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1989–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naik Bukke A, Nazneen Hadi F, Babu KS, Shankar PC. In vitro studies data on anticancer activity of Caesalpinia sappan L. heartwood and leaf extracts on MCF7 and A549 cell lines. Data Brief. 2018;19:868–877. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao XF, Li QL, Li HL, Zhang HY, Su JY, Wang B, Liu P, Zhang AQ. Extracts from Curcuma zedoaria inhibit proliferation of human breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231 in vitro. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014(730678) doi: 10.1155/2014/730678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamborlin L, Sumere BR, de Souza MC, Pestana NF, Aguiar AC, Eberlin MN, Simabuco FM, Rostagno MA, Luchessi AD. Characterization of pomegranate peel extracts obtained using different solvents and their effects on cell cycle and apoptosis in leukemia cells. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:5483–5496. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dikmen M, Ozturk N, Ozturk Y. The antioxidant potency of Punica granatum L. Fruit peel reduces cell proliferation and induces apoptosis on breast cancer. J Med Food. 2011;14:1638–1646. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shapira N. The potential contribution of dietary factors to breast cancer prevention. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017;26:385–395. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao W, Li XQ, Wang X, Fan HT, Zhang XN, Hou Y, Liu SB, Mei QB. A novel polysaccharide, isolated from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels induces the apoptosis of cervical cancer HeLa cells through an intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nalini N, Manju V, Menon VP. Effect of spices on lipid metabolism in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced rat colon carcinogenesis. J Med Food. 2006;9:237–245. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee TK, Lee D, Lee SR, Ko YJ, Sung Kang K, Chung SJ, Kim KH. Sesquiterpenes from Curcuma zedoaria rhizomes and their cytotoxicity against human gastric cancer AGS cells. Bioorg Chem. 2019;87:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapinova A, Kubatka P, Golubnitschaja O, Kello M, Zubor P, Solar P, Pec M. Dietary phytochemicals in breast cancer research: Anticancer effects and potential utility for effective chemoprevention. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(36) doi: 10.1186/s12199-018-0724-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4(177) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsugawa H, Cajka T, Kind T, Ma Y, Higgins B, Ikeda K, Kanazawa M, VanderGheynst J, Fiehn O, Arita M. MS-DIAL: Data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat Methods. 2015;12:523–526. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jevapatarakul D, T-Thienprasert J, Payungporn S, Chavalit T, Khamwut A, T-Thienprasert NP. Utilization of Cratoxylum formosum crude extract for synthesis of ZnO nanosheets: Characterization, biological activities and effects on gene expression of nonmelanoma skin cancer cell. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130(110552) doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(550) doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11(R14) doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, Yamanishi Y. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gong H, Sun L, Chen B, Han Y, Pang J, Wu W, Qi R, Zhang TM. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in three metabolism related tissues of mice after caloric restriction. Sci Rep. 2016;6(38513) doi: 10.1038/srep38513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daneshforouz A, Nazemi S, Gholami O, Kafami M, Amin B. The cytotoxicity and apoptotic effects of verbascoside on breast cancer 4T1 cell line. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;22(72) doi: 10.1186/s40360-021-00540-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi W, Li F, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Yang X, Zhu J, Wu F, Ouyang H, Ge J, et al. Caspase-8 promotes NLRP1/NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production in acute glaucoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11181–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402819111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu W, Guo G, Li J, Ding Z, Sheng J, Li J, Tan W. Activation of Bcl-2-Caspase-9 apoptosis pathway in the testis of asthmatic mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(e0149353) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SH, Cho YC, Lim JS. Costunolide, a sesquiterpene lactone, suppresses skin cancer via induction of apoptosis and blockage of cell proliferation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2075) doi: 10.3390/ijms22042075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang H, Yi J, Park S, Zhang H, Kim E, Park S, Kwon W, Jang S, Zhang X, Chen H, et al. Costunolide suppresses melanoma growth via the AKT/mTOR pathway in vitro and in vivo. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11:1410–1427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho E, Chung EY, Jang HY, Hong OY, Chae HS, Jeong YJ, Kim SY, Kim BS, Yoo DJ, Kim JS, Park KH. Anti-cancer Effect of Cyanidin-3-glucoside from Mulberry via Caspase-3 Cleavage and DNA Fragmentation in vitro and in vivo. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2017;17:1519–1525. doi: 10.2174/1871520617666170327152026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang L, Liu X, He J, Shao Y, Liu J, Wang Z, Xia L, Han T, Wu P. Cyanidin-3-glucoside induces mesenchymal to epithelial transition via activating Sirt1 expression in triple negative breast cancer cells. Biochimie. 2019;162:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen HY, Cheng WP, Chiang YF, Hong YH, Ali M, Huang TC, Wang KL, Shieh TM, Chang HY, Hsia SM. Hinokitiol exhibits antitumor properties through induction of ROS-Mediated apoptosis and p53-Driven cell-cycle arrest in endometrial cancer cell lines (Ishikawa, HEC-1A, KLE) Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8268) doi: 10.3390/ijms22158268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu YJ, Hsu WJ, Wu LH, Liou HP, Pangilinan CR, Tyan YC, Lee CH. Hinokitiol reduces tumor metastasis by inhibiting heparanase via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase B pathway. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:403–413. doi: 10.7150/ijms.41177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamagata K, Uzu E, Yoshigai Y, Kato C, Tagami M. Oleic acid and oleoylethanolamide decrease interferon-ү-induced expression of PD-L1 and induce apoptosis in human lung carcinoma cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;903(174116) doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.To NB, Nguyen YT, Moon JY, Ediriweera MK, Cho SK. Pentadecanoic acid, an odd-chain fatty acid, suppresses the stemness of MCF-7/SC human breast cancer stem-like cells through JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Nutrients. 2020;12(1663) doi: 10.3390/nu12061663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pei J, Velu P, Zareian M, Feng Z, Vijayalakshmi A. Effects of syringic acid on apoptosis, inflammation, and AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in gastric cancer cells. Front Nutr. 2021;8(788929) doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.788929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nizamutdinova IT, Lee GW, Son KH, Jeon SJ, Kang SS, Kim YS, Lee JH, Seo HG, Chang KC, Kim HJ. Tanshinone I effectively induces apoptosis in estrogen receptor-positive (MCF-7) and estrogen receptor-negative (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang EW, Xue SJ, Zhang Z, Zhou JG, Guan YY, Tang YB. Vinpocetine inhibits breast cancer cells growth in vitro and in vivo. Apoptosis. 2012;17:1120–1130. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim DH, Sung B, Chung HY, Kim ND. Modulation of Colitis-associated colon tumorigenesis by baicalein and betaine. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:153–160. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2014.19.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye B, Aponte M, Dai Y, Li L, Ho MC, Vitonis A, Edwards D, Huang TN, Cramer DW. Ginkgo biloba and ovarian cancer prevention: Epidemiological and biological evidence. Cancer Lett. 2007;251:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong CH, Chang WL, Lu FJ, Liu YW, Peng JY, Chen CH. Parecoxib expresses anti-metastasis effect through inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in human colon cancer DLD-1 cell line. Environ Toxicol. 2022;37:2718–2727. doi: 10.1002/tox.23631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang Z, Chen H, Tan P, Huang M, Shi H, Sun B, Cheng Y, Li T, Mou Z, Li Q, Fu W. Sinapic acid inhibits pancreatic cancer proliferation, migration, and invasion via downregulation of the AKT/Gsk-3β signal pathway. Drug Dev Res. 2022;83:721–734. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng Q, Luo C, Cho J, Lai D, Shen X, Zhang X, Zhou W. Tryptanthrin exerts anti-breast cancer effects both in vitro and in vivo through modulating the inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Acta Pharm. 2021;71:245–266. doi: 10.2478/acph-2021-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu X, Lin H, Wang Y, Lv W, Zhang S, Qian Y, Deng X, Feng N, Yu H, Qian B. d-limonene exhibits antitumor activity by inducing autophagy and apoptosis in lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:1833–1847. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S155716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramasamy S, Abdul Wahab N, Zainal Abidin N, Manickam S, Zakaria Z. Growth inhibition of human gynecologic and colon cancer cells by Phyllanthus watsonii through apoptosis induction. PLoS One. 2012;7(e34793) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cao Y, Wang Q, Du Y, Liu F, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Jin F. l-arginine and docetaxel synergistically enhance anti-tumor immunity by modifying the immune status of tumor-bearing mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;35:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ganapathy V, Gopal E, Miyauchi S, Prasad PD. Biological functions of SLC5A8, a candidate tumour suppressor. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 1):237–240. doi: 10.1042/BST0330237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coothankandaswamy V, Elangovan S, Singh N, Prasad PD, Thangaraju M, Ganapathy V. The plasma membrane transporter SLC5A8 suppresses tumour progression through depletion of survivin without involving its transport function. Biochem J. 2013;450:169–178. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piao XM, Jeong P, Yan C, Kim YH, Byun YJ, Xu Y, Kang HW, Seo SP, Kim WT, Lee JY, et al. A novel tumor suppressing gene, ARHGAP9, is an independent prognostic biomarker for bladder cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020;19:476–486. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.11123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun J, Zhao X, Jiang H, Yang T, Li D, Yang X, Jia A, Ma Y, Qian Z. ARHGAP9 inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation, invasion and EMT via targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Tissue Cell. 2022;77(101817) doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2022.101817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Z, Li M, Jiang Z, Wang X. A Comprehensive immunologic portrait of triple-negative breast cancer. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:311–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Diermeier SD, Chang KC, Freier SM, Song J, El Demerdash O, Krasnitz A, Rigo F, Bennett CF, Spector DL. Mammary tumor-associated RNAs impact tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Cell Rep. 2016;17:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ichim G, Tait SW. A fate worse than death: Apoptosis as an oncogenic process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:539–548. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-sequencing datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (accession no. SRR18848741-SRR18848746 and SRR18848748-SRR18848753). The data are also available through the NCBI GenBank (accession no. PRJNA830310).

All other data used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.