Abstract

Rationale

Sarcoidosis is a racially disparate granulomatous disease likely caused by environmental exposures, genes, and their interactions. Despite increased risk in African Americans, few environmental risk factor studies in this susceptible population exist.

Objectives

To identify environmental exposures associated with the risk of sarcoidosis in African Americans and those that differ in effect by self-identified race and genetic ancestry.

Methods

The study sample comprised 2,096 African Americans (1,205 with and 891 without sarcoidosis) compiled from three component studies. Unsupervised clustering and multiple correspondence analyses were used to identify underlying clusters of environmental exposures. Mixed-effects logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of these exposure clusters and the 51 single-component exposures with risk of sarcoidosis. A comparison case-control sample of 762 European Americans (388 with and 374 without sarcoidosis) was used to assess heterogeneity in exposure risk by race.

Results

Seven exposure clusters were identified, five of which were associated with risk. The exposure cluster with the strongest risk association was composed of metals (P < 0.001), and within this cluster, exposure to aluminum had the highest risk (odds ratio, 3.30; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.23–4.09; P < 0.001). This effect also differed by race (P < 0.001), with European Americans having no significant association with exposure (odds ratio, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.56–1.33). Within African Americans, the increased risk was dependent on genetic African ancestry (P = 0.047).

Conclusions

Our findings support African Americans having sarcoidosis environmental exposure risk profiles that differ from those of European Americans. These differences may underlie racially disparate incidence rates that are partially explained by genetic variation differing by African ancestry.

Keywords: sarcoidosis, environment, racial disparity, genetic ancestry

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan-system granulomatous disease that is likely driven by environmental exposures, heritable genetic factors, and the interactions between them (1). Genetic studies have shown that a portion of the trait variance is due to variation in the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) class II genes (2, 3). Although multiple reports of environmental risk factors for sarcoidosis exist in the literature (4–10), few include minority populations at high risk of sarcoidosis, such as African Americans (11).

To date, the most comprehensive study of environmental risk factors for sarcoidosis was conducted by the multicenter study ACCESS (A Case Control Etiologic Sarcoidosis Study). ACCESS found evidence for multiple environmental risk factors with modest effects (8). Although nearly half of the ACCESS sample was African American, the study did not explore environmental factors that may differ in risk by race in the original report; a subsequent analysis of environmental exposures associated with different disease phenotypes did find some associations that differed by race (12). Further, even though evidence suggests that genetic African ancestry partially explains the disparity in sarcoidosis risk between African Americans and European Americans (13), no studies exist that have investigated whether the degree of genetic African ancestry among African Americans modifies the risk associated with environmental exposures.

The present investigation combines primary data from three component studies to explore the associations of environmental exposures with risk of sarcoidosis in African Americans. Multiple multi-exposure statistical approaches were used to characterize the profile of environmental risk factors associated with sarcoidosis susceptibility in this high-risk minority population (11, 14–16). To identify environmental factors that may explain a portion of the nearly fourfold higher incidence rate in African Americans compared with European Americans (11), differential effects of environmental exposures by self-reported race/ethnicity were also assessed. Finally, we used existing genome-wide estimates of African ancestry (17) to evaluate whether exposures that have differential effects on risk by race could be explained by an underlying genetic mechanism in African Americans (i.e., genetic African ancestry–by–environmental interactions).

Methods

Detailed methods are described in the data supplement.

Study Subjects

The study sample includes 2,096 self-identified African Americans (1,205 with and 891 without sarcoidosis) and was assembled from the following three studies: 1) ACCESS (18), 2) a multisite affected-sibling sarcoidosis linkage study (19), and 3) a nuclear family–based sample ascertained through a single affected individual (20). The varied sampling schemes across studies resulted in a final analytic sample of related and unrelated cases and control subjects. Additionally, the European American ACCESS participants (388 with and 374 without sarcoidosis) were also included for the purpose of comparison. A descriptive summary of the primary African American study samples contributing to the environmental analyses is presented in Table 1, and a similar summary for the contribution of each of the component studies is presented in Table E1 in the data supplement. All study protocols were approved by the Henry Ford Health System (Detroit, MI) Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Description of overall environmental and ancestry interaction analysis groups

| Variable | Overall (N = 2,096) |

Ancestry Interactions (n = 1,858) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case (n = 1,205) | Control (n = 891) | P Value* | Case (n = 1,057) | Control (n = 801) | P Value* | |

| Component study | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| HFHS | 344 (40.5) | 506 (59.5) | 287 (38.0) | 469 (62. 0) | ||

| SAGA | 540 (87.0) | 81 (13.0) | 530 (86.9) | 80 (13.1) | ||

| ACCESS | 321 (51.4) | 304 (48.6) | 240 (48.8) | 252 (51.2) | ||

| Sex | 0.007 | 0.004 | ||||

| Female | 892 (74.0) | 611 (68.6) | 795 (59.0) | 553 (41.0) | ||

| Male | 313 (26.0) | 280 (31.4) | 262 (48.6) | 248 (51.4) | ||

| African ancestry, %† | — | — | — | 83.0 ± 9.7 | 81.3 ± 11.7 | 0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: ACCESS = A Case-Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis; HFHS = Henry Ford Health System; SAGA = SArcoidosis Genetic Analysis.

Values presented as count (row percentage) or mean ± standard deviation. The analysis groups are defined as follows: 1) “overall” refers to the African American study participants contributing to the environmental exposure cluster analysis, single cluster/environmental exposure analyses, multiexposure model, and environmental exposure–by–race interaction analyses; and 2) “ancestry interactions” refers to African American study participants contributing to the analyses testing the interaction between environmental exposures and genome-wide percentage of African ancestry among African American study participants.

P value calculated by χ2 test for sex/component studies and t test for African ancestry percentage.

Genome-wide African ancestry percentage for African American study participants.

Environmental Exposure Assessment

Data for individuals were collected in person by trained interviewers. The questionnaires used for the two family-based studies were reduced versions of the questionnaire used in ACCESS, which was constructed from exposures that were plausibly associated with sarcoidosis risk based on the literature. Whereas ACCESS solely enrolled incident cases, the two family-based studies enrolled incident and prevalent cases. Although subjects in each of the studies were asked exposure questions focused on the time before disease diagnosis, the prevalent cases had an additional period of time between diagnosis and their exposure assessment, which may have impacted their recall relative to the incident cases. The common questions across the three instruments primarily assessed dichotomous exposures, including jobs, hobbies, and exposures at home and at work. For tobacco use, ever-users were also asked detailed questions to assess the duration and intensity of exposure (8, 18). In total, 65 environmental and occupational exposures were assessed in all three of the component studies. The analyses presented here are restricted to 51 exposures with <5% missing data.

Statistical Analyses

To determine if evidence exists for underlying groupings of exposures within the African American sample, all dichotomous exposure variables (ever vs. never exposed) were clustered using multiple correspondence analysis implemented in the variable clustering ClustOfVar R package (21). Briefly, this algorithm attempts to generate groupings of highly correlated exposures by maximizing homogeneity within clusters, whereby the homogeneity measure is defined by the link between the variables in the cluster and its central synthetic variable, defined as the first principal component from multiple correspondence analysis (22). A bootstrap approach was used to determine the number of exposure clusters. Missing data were accounted for as a third category for each of the exposures.

Mixed-effect logistic regression was used to assess the association between sarcoidosis affection status and each of the synthetic environmental exposures and the component exposures to account for first-degree relationships, adjusted for sex. Statistical significance was assessed using a likelihood ratio test. To test for heterogeneity in each exposure effect by race, we compared models with and without an exposure-by-race multiplicative interaction term. For significant interactions, similar exposure– by–genome-wide African ancestry interactions among African Americans were tested, with African ancestry estimates derived from a prior study (17). P value adjustment for multiple comparisons was achieved using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) approach.

A multiexposure model was constructed using a multiple imputation procedure. Specifically, exposures with missing values were imputed using the multivariate imputation by chained equations method (23). For each imputed dataset, a logistic mixed model was fit using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator penalty. The procedure of imputation and model estimation was performed five times, and exposures that were selected at least once in the five datasets were used for the final model. Finally, the parameter estimates of the selected exposure variables from five datasets were combined using Rubin’s rules (24).

Results

African American Environmental Exposure Clusters

The frequencies for the 51 exposures in sarcoidosis cases and controls are presented in Table E2. The most parsimonious exposure clustering solution consisted of seven exposure clusters (Figure E1), which are displayed in Figure 1. With few exceptions, the seven exposure clusters are consistent with the following descriptions: 1) smoke, 2) work history, 3) farm/outdoor animals, 4) sources of humidity, 5) mold/musty odors, 6) household pets, and 7) metals.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram resulting from unsupervised hierarchical clustering of exposures among African Americans with and without sarcoidosis. The hashed line indicates the threshold at which the dendrogram was cut, resulting in seven exposure clusters, each indicated by a different color of the component exposures on the right side of the dendrogram (from top to bottom, pink indicates smoke, blue indicates work history, teal indicates farm/outdoor animals, light green indicates sources of humidity, dark green indicates mold/musty odors, yellow indicates household pets, and red indicates metals).

Single-Exposure Cluster and Individual Exposure Risk Associations in African Americans

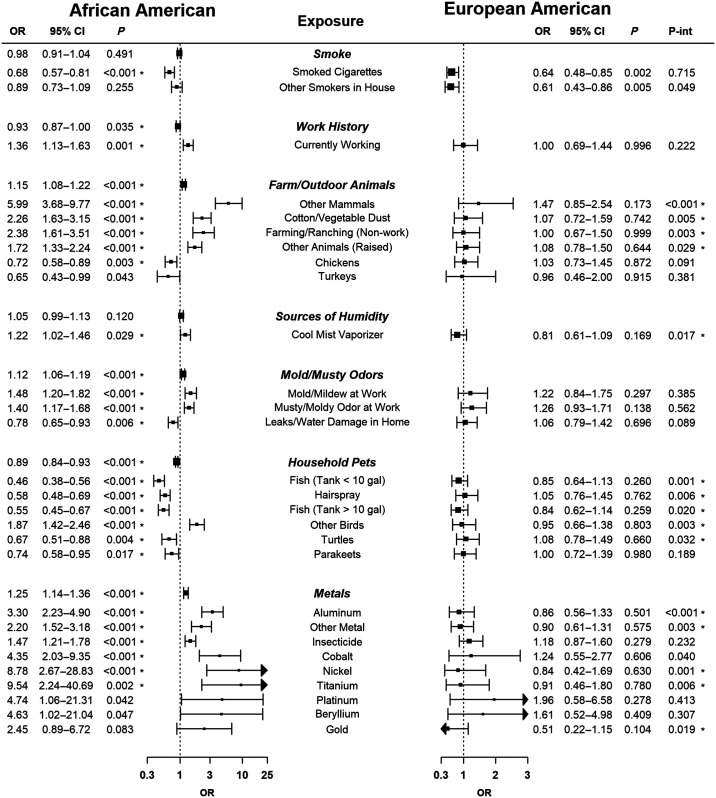

Association findings between the seven clusters and sarcoidosis risk are presented in Figure 2. The farm animals/hospital, mold/musty odor, and metals exposure clusters were each associated with increased risk of sarcoidosis. The smoke and household pet clusters were associated with a protective effect.

Figure 2.

Univariate sarcoidosis risk association results for exposure clusters and significant (P < 0.05) component exposures for African Americans or European Americans. For each exposure cluster, the odds ratio corresponds to a one-unit change in the first principal component for that cluster obtained from a multiple correspondence analysis of the component exposures. For the component exposures, each is dichotomous (i.e., ever vs. never exposed). For the African American and race interaction analyses, an asterisk adjacent to the P value further indicates a test with a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate–adjusted significance level lower than 0.05. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; P-int = P value for the race-by-exposure interaction term.

For each individual exposure, the sarcoidosis risk association results are presented in the full sample and separated by study design (independent case-control, ACCESS; and family-based, Henry Ford Health System study and SAGA [SArcoidosis Genetic Analysis]) in Table E3. Overall, 26 exposures were associated (P < 0.05) with the risk of sarcoidosis, 22 of which remained after adjustment for multiple testing (FDR < 0.05), and, in a subanalysis restricting the cases to those that were biopsy-confirmed (n = 903), all 26 remained associated with risk (Table E4). There was agreement in the direction of effect for the cluster and single exposures. In particular, the component exposures of the mold/musty odor and metal clusters were all associated with an increased risk of disease. Within the metal cluster, the most prominent exposure was aluminum (odds ratio [OR], 3.30; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.23–4.90; P < 0.001). Insecticide exposure also clustered with the metals and was associated with increased risk (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.22–1.78; P < 0.001). Exposures within the farm cluster were also predominantly associated with increased risk, exemplified by the category “other farm mammals” (OR, 5.99; 95% CI, 3.68–9.77; P < 0.001). However, exposure to chickens and turkeys was associated with a protective effect.

The exposures in the household pet cluster were generally associated with protective effects, the most prominent association being fish tank exposure, with similar effects for exposure to smaller (<10 gal; OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.38–0.56; P < 0.001) and larger (>10 gal; OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.45–0.67; P < 0.001) tanks. The only nonanimal exposure in this cluster was hairspray, which was also associated with a protective effect. A notable exception to the protective trend within this cluster was exposure to “other birds” (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.42–2.46; P < 0.001).

Within the smoke exposure cluster, cigarette and pipe smoking were associated with a protective effect (Figure 2). African Americans with sarcoidosis were less likely to report ever having smoked cigarettes (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.57–0.81; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Among ever-smokers, subjects with sarcoidosis reported smoking fewer cigarettes per day (per-cigarette OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97–0.98; P < 0.001).

Exposure Effect Modification by Self-reported Race and Genetic African Ancestry

Of the 17 exposures showing differential effects by race (P < 0.05 for interaction; 15 with interaction FDR < 0.05; Figure 2), 15 were associated with risk in African Americans. The most prominent differential effect was exposure to aluminum (P < 0.001 for interaction). Compared with the increased risk of disease among African Americans, the effect among European Americans did not differ from the null (Figure 2). This pattern was consistent with the five other exposures in the metal cluster that showed association with risk in African Americans (Figure 2). African Americans also had stronger increased risk related to farm animals, best exemplified by other farm mammals (P < 0.001 for interaction), and stronger protective effects related to indoor pets, exemplified by exposure to fish tanks (<10 gal; P < 0.001 for interaction).

Although the majority of exposures that differed by race/ethnicity had more extreme effects in African Americans, a notable exception was secondhand smoke. Specifically, reporting other smokers in one’s home was associated with a protective effect among European Americans (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.43–0.86; P = 0.005) that was stronger than the effect in African Americans (P = 0.049 for interaction).

Exposure Effect Modification by Genetic Ancestry in African Americans

For the race-by-exposure interactions identified (P < 0.05 for interaction), we tested whether exposure effects on the risk of sarcoidosis depended on genome-wide percentage of African ancestry among African Americans. The fish tank and aluminum exposure effects depended on the percentage of African ancestry. First, for the fish tank exposure, an increasing proportion of genetic African ancestry was associated with an increasingly protective effect of exposure to a fish tank (P = 0.02 for ancestry interaction; Figure 3), consistent with the stronger protective effect in African Americans relative to European Americans. Second, an increasing proportion of genetic African ancestry was associated with an increasing risk effect of aluminum exposure (P = 0.047 for ancestry interaction; Figure 3), consistent with the higher risk associated with exposure in African Americans versus European Americans.

Figure 3.

The effects of a household fish tank and aluminum exposure on the risk of sarcoidosis are dependent on the percentage of genome-wide African ancestry among African Americans. For the fish tank (top) and aluminum (bottom) exposure, odds ratios and 95% CIs are displayed for each stratum of percentage of genome-wide African ancestry (⩽60%, >60% to 70%, >70% to 80%, >80% to 90%, and >90% to 100%). As the percentage of African ancestry increases, the fish tank exposure becomes increasingly protective whereas the detrimental effect of aluminum on sarcoidosis risk becomes more pronounced. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Multivariable Model of Exposures and Sarcoidosis Risk in African Americans

Given the self-reported race/ethnicity–specific exposure effects, a multiexposure model of sarcoidosis risk was constructed in African Americans alone. The resulting model included 11 exposures (Table 2), all of which were individually associated with risk (Figure 2), and the multivariable OR estimates were also consistent with the direction of the univariate estimates, even though the magnitudes of the effects were diminished. Of note, aluminum and fish tank exposure had the most prominent differences in effect between African Americans and European Americans, and both were retained in the multiexposure model. Among the exposures associated with increased risk, four farm/outdoor animal exposures were retained, along with exposures to other birds and insecticides. Among the protective exposures, ever-exposure to smoking cigarettes remained associated with decreased sarcoidosis risk.

Table 2.

Multivariable model of exposures associated with sarcoidosis risk in African Americans

| Cluster/Exposure | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Smoking (ever smoked cigarettes) | 0.68 (0.58–0.80) |

| Farm/outdoor animals | |

| Other mammals | 3.05 (2.08–4.48) |

| Other animals | 0.98 (0.76–1.25) |

| Farming or ranching | 1.11 (0.82–1.50) |

| Cotton/vegetable dust | 1.32 (1.01–1.72) |

| Household pets | |

| Other birds | 1.32 (1.05–1.68) |

| Fish (tank >10 gal) | 0.62 (0.52–0.74 |

| Fish (tank <10 gal) | 0.60 (0.50–0.71) |

| Hairspray | 0.81 (0.68–0.95) |

| Metals | |

| Aluminum | 1.48 (1.11–1.98) |

| Insecticide | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) |

Definition of abbreviation: 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

The model was constructed based on five component least absolute shrinkage and selection operator penalized logistic regression mixed models constructed using multiple imputation by chained equations to account for missing data. The final model was composed of those exposures that were included in a majority (i.e., three or more) of the five component models. All component models were adjusted for sex.

Discussion

Previously, the ACCESS investigators reported multiple exposures with modestly increased risks for sarcoidosis. The present study adds further support to multiple exposures as risk factors for sarcoidosis identified in ACCESS (8) including, but not limited to, protective effects of tobacco exposure (e.g., ever smoking cigarettes) and risk-increasing effects of metals and insecticides. Interestingly, ACCESS also identified potential bioaerosols with risk-protective (e.g., home fish tanks) and risk-increasing (e.g., mold/musty odors) effects. Although the original ACCESS analysis did not evaluate evidence for race-specific effects, a subsequent analysis of ACCESS data that focused on environmental exposures associated with specific disease phenotypes did report race-specific environmental associations (12).

Investigating the risk of systemic sarcoidosis, Kreider and colleagues found exposure to agricultural organic dust at work to be protective only in European Americans and wood-burning exposure to be protective only in African Americans, although formal heterogeneity testing of risk differences by race was not performed (12). A novel contribution of the present study was its testing of the assumption of homogeneity of effects by combining the ACCESS study data with additional exposure data in African Americans.

Although there were notable associations of smoking and reported mold/musty odors that did not appear to have differential effects between African Americans and European Americans, novel race-specific exposure effects were found. The strongest evidence of differences by race were for aluminum and indoor fish tank exposures. In particular, aluminum was the metal exposure with the strongest risk association, but only in African Americans. Aluminum is the most widely distributed metal in the environment, and in a previous study of 648 African American siblings with one or more sarcoidosis-affected individuals, we reported metal machining as an occupational risk factor for sarcoidosis (7).

In terms of direct exposure to aluminum and sarcoidosis, the best evidence comes from the case-report literature of granulomatous skin reactions and histologic evidence of sarcoid granuloma within tattoos (25). Sarcoidal granulomas are known to infiltrate tattoos, dissipate with treatment, and recur with disease activity. Carbon, titanium, and aluminum are three of the common elements used as tattoo colorants (26, 27). Further, in a death certificate–based study of occupational exposures and sarcoidosis, Liu and colleagues found that a history of working in an occupation with exposure to metals had a significantly stronger detrimental effect on sarcoidosis-related mortality in African Americans than in European Americans (28). This finding was consistent with one from an ACCESS occupational exposure study by Barnard and colleagues that identified a detrimental effect of occupational metal dust exposure in African Americans but not in European Americans (4). These differential effects are consistent with our findings, strengthening support of the existence of race-specific metal exposure effects.

In contrast to the race-restricted effect of aluminum, the protective effect of exposure to indoor fish tanks was evident in both races but was more pronounced in African Americans. Given the connections between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and sarcoidosis (29) and the genetic similarity between Mycobacterium marinum and M. tuberculosis, the protective effect of fish tanks may be related to an induced state of immune tolerance resulting from exposure to M. marinum in susceptible individuals. Although this may seem improbable given that M. marinum infection is a well-known cause of “fish tank granuloma” (30), M. marinum has been investigated as a potential immunotherapy for tuberculosis (31). Another possible explanation could be related to stress reduction, given that the magnitude of stressful life events was significantly higher in patients with sarcoidosis compared with healthy controls (32). However, both are speculative and would require mechanistic study.

In addition to these race-by-exposure interactions, these exposure effects were also modified by the genome-wide percentage of African ancestry among African Americans in the directions consistent with the observed interactions by race. Although the present study did not explore the specific genetic variation underlying these interactions, the literature supports that gene–environment interactions drive disease pathogenesis in sarcoidosis (33), and evidence of gene–environment interaction effects influencing risk of sarcoidosis (34–36) has begun to emerge. For example, using ACCESS data, Rossman and colleagues identified potential gene–environment interaction between insecticide and mold exposures and known susceptibility alleles in HLA-DRB1 (35). Using a genome-wide approach, we recently identified an interaction between the gene FUT9 and insecticide exposure that impacts sarcoidosis susceptibility (36).

As noted earlier, associations with some of the environmental exposures assessed in the ACCESS study have been reported previously as simple exposure–disease relationships (4, 8), as well as in the context of specific disease phenotypes (12) and gene–environment interactions (35). Other disease–exposure associations involving portions of the present study dataset have also been reported (7, 37). Our study was unique, however, in its use of multiple multivariate techniques to gain insight into risk-associated exposures. In particular, the use of unsupervised clustering facilitated insight into the relationship between risk-associated exposures. An unexpected result was the clustering of insecticide exposure within the metal cluster. Consistent with the increased sarcoidosis risk observed for individual metals studied, exposure to insecticides was also associated with increased risk of disease in African Americans. It is known that some insecticides contain inorganic elements, including metals. Exposure to insecticides has been associated with several pulmonary conditions, including farmer’s lung (38), asthma (39), and decreased lung function (40, 41).

Although this is the largest study of environmental exposures and risk of sarcoidosis in African American subjects, there are multiple limitations of note. The most important limitation to the study is possible differential recall between cases and controls due to the retrospective exposure assessment. One potentially affected finding is the protective effect of ever smoking (8, 42, 43). Although possible recall or detection bias cannot be ruled out, this protective effect is supported by prior reports and by evidence in this study of a more intense smoking history (i.e., more cigarettes per day and an early age of smoking onset) among controls relative to cases. Although aluminum is a component of tobacco products (44, 45), the risk-protective effect may be related to the antiinflammatory properties of nicotine, which is being explored as a pulmonary sarcoidosis therapeutic agent (46).

Other study limitations are evident. First, there is no independent African American cohort available to validate the study’s primary findings. However, it is evident from the results in Table E3 that there was consistency in effects across ACCESS and the family-based studies for the majority of the findings. Second, the European American sample used to identify differential race effects was significantly smaller than the African American sample. Although this difference is not likely to bias the findings, it certainly reduces the statistical power to detect more subtle race-specific effects, especially those that are unique to European Americans. Third, misdiagnosis of other granulomatous diseases as sarcoidosis is a possibility, and even though the sensitivity analysis based on biopsy-confirmed cases in African Americans showed consistent effects, the potential for misdiagnosis to influence the results cannot be completely ruled out. Fourth, we did not have information on timing of exposure across all of the studies, which is likely important information that would give further insight into these exposure relationships with risk. Finally, exposure doses were not available, with the exception of smoking. This information could provide additional insights into exposure associations with the risk of sarcoidosis, which should be captured in future studies.

In summary, this study sheds further light on exposures related to the risk of sarcoidosis in African Americans through an evaluation of the correlated nature of these exposures and race-specific exposure risk effects. Further, among African Americans, the modification of the risk associations of fish tank and aluminum exposure by African ancestry provides further evidence of the contribution of gene-by-environment interactions to sarcoidosis susceptibility. Future large studies to identify the specific genetic variants that contribute to these interactions in African Americans may have implications for the prevention and treatment of sarcoidosis in this minority population that suffers disproportionately from this disease. However, in trying to understand the underlying causes of exposure effects that differ by race, one cannot overlook the potential of racial bias in the diagnostic workup of sarcoidosis cases and even in the exposure assessment that could lead to spurious results. Reports of disparate disease outcomes for low-income African Americans support this possibility (47, 48), and future studies should be appropriately designed to minimize or eliminate such biases and explore measures of structural racism as potential contributory exposures to the differences in risk of sarcoidosis between African Americans and European Americans.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–funded ACCESS and SAGA research groups for original data collection efforts, as well as the participants in these studies.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R21HL129023-01 (A.M.L.), R61AR076803 and P20GM103456 (I.A.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants 1RC2HL101499 and R01HL113326 (C.G.M.), R01-HL54306 and U01-HL060263 (M.C.I.), and R56-AI072727 and R01-HL092576 (B.A.R.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: A.M.L., M.C.I., and B.A.R. Analysis and interpretation: A.M.L., R.S., Y.C., I.A., I.D., I.M.L., L.G., C.G.M., J.L., M.C.I., and B.A.R. Drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: A.M.L., R.S., I.A., C.G.M., J.L., M.C.I., and B.A.R. All authors contributed to and approved the final submitted manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis: recent advances and future prospects. Semin Respir Crit Care Med . 2007;28:22–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossman MD, Thompson B, Frederick M, Maliarik M, Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, et al. ACCESS Group HLA-DRB1*1101: a significant risk factor for sarcoidosis in blacks and whites. Am J Hum Genet . 2003;73:720–735. doi: 10.1086/378097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gardner J, Kennedy HG, Hamblin A, Jones E. HLA associations in sarcoidosis: a study of two ethnic groups. Thorax . 1984;39:19–22. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnard J, Rose C, Newman L, Canner M, Martyny J, McCammon C, et al. ACCESS Research Group Job and industry classifications associated with sarcoidosis in A Case-Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS) J Occup Environ Med . 2005;47:226–234. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000155711.88781.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jajosky P. Sarcoidosis diagnoses among U.S. military personnel: trends and ship assignment associations. Am J Prev Med . 1998;14:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kajdasz DK, Lackland DT, Mohr LC, Judson MA. A current assessment of rurally linked exposures as potential risk factors for sarcoidosis. Ann Epidemiol . 2001;11:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kucera GP, Rybicki BA, Kirkey KL, Coon SW, Major ML, Maliarik MJ, et al. Occupational risk factors for sarcoidosis in African-American siblings. Chest . 2003;123:1527–1535. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, Rossman MD, Barnard J, Frederick M, et al. ACCESS Research Group A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2004;170:1324–1330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jordan HT, Stellman SD, Prezant D, Teirstein A, Osahan SS, Cone JE. Sarcoidosis diagnosed after September 11, 2001, among adults exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. J Occup Environ Med . 2011;53:966–974. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822a3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Terčelj M, Salobir B, Harlander M, Rylander R. Fungal exposure in homes of patients with sarcoidosis—an environmental exposure study. Environ Health . 2011;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Jr, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol . 1997;145:234–241. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreider ME, Christie JD, Thompson B, Newman L, Rose C, Barnard J, et al. Relationship of environmental exposures to the clinical phenotype of sarcoidosis. Chest . 2005;128:207–215. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rybicki BA, Levin AM, McKeigue P, Datta I, Gray-McGuire C, Colombo M, et al. A genome-wide admixture scan for ancestry-linked genes predisposing to sarcoidosis in African-Americans. Genes Immun . 2011;12:67–77. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wills AB, Adjemian J, Fontana JR, Steiner CA, Daniel-Wayman S, Olivier KN, et al. Sarcoidosis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:1490–1493. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201806-401RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogundipe F, Mehari A, Gillum R. Disparities in sarcoidosis mortality by region, urbanization, and race in the United States: a multiple cause of death analysis. Am J Med . 2019;132:1062–1068.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, Rossman MD, Yeager H, Jr, Bresnitz EA, et al. Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS) research group Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2001;164:1885–1889. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levin AM, Iannuzzi MC, Montgomery CG, Trudeau S, Datta I, Adrianto I, et al. Admixture fine-mapping in African Americans implicates XAF1 as a possible sarcoidosis risk gene. PLoS One . 2014;9:e92646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. ACCESS Research Group. Design of a case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS) J Clin Epidemiol . 1999;52:1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rybicki BA, Hirst K, Iyengar SK, Barnard JG, Judson MA, Rose CS, et al. A sarcoidosis genetic linkage consortium: the Sarcoidosis Genetic Analysis (SAGA) study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2005;22:115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iannuzzi MC, Maliarik MJ, Poisson LM, Rybicki BA. Sarcoidosis susceptibility and resistance HLA-DQB1 alleles in African Americans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2003;167:1225–1231. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1097OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chavent M, Simonet VK, Liquet B, Saracco J. ClustOfVar: an R package for the clustering of variables J Stat Softw 2012. 50 1 16 25317082 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chavent M, Kuentz-Simonet V, Saracco J. Orthogonal rotation in PCAMIX. Adv Data Anal Classif . 2012;6:131–146. [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw . 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kluger N. Sarcoidosis on tattoos: a review of the literature from 1939 to 2011. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2013;30:86–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beute TC, Miller CH, Timko AL, Ross EV. In vitro spectral analysis of tattoo pigments. Dermatol Surg . 2008;34:508–515, discussion 515–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Timko AL, Miller CH, Johnson FB, Ross E. In vitro quantitative chemical analysis of tattoo pigments. Arch Dermatol . 2001;137:143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu H, Patel D, Welch AM, Wilson C, Mroz MM, Li L, et al. Association between occupational exposures and sarcoidosis: an analysis from death certificates in the United States, 1988-1999. Chest . 2016;150:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med . 2007;357:2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu TS, Chiu CH, Yang CH, Leu HS, Huang CT, Chen YC, et al. Fish tank granuloma caused by Mycobacterium marinum. PLoS One . 2012;7:e41296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tian WW, Wang QQ, Liu WD, Shen JP, Wang HS. Mycobacterium marinum: a potential immunotherapy for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Drug Des Devel Ther . 2013;7:669–680. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S45197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamada Y, Tatsumi K, Yamaguchi T, Tanabe N, Takiguchi Y, Kuriyama T, et al. Influence of stressful life events on the onset of sarcoidosis. Respirology . 2003;8:186–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Culver DA, Newman LS, Kavuru MS. Gene-environment interactions in sarcoidosis: challenge and opportunity. Clin Dermatol . 2007;25:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossman M, Thompson B, Frederick M, Cizman B, Magira E, Monos D. Sarcoidosis: association with human leukocyte antigen class II amino acid epitopes and interaction with environmental exposures. Chest . 2002;121:14S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3_suppl.14s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rossman MD, Thompson B, Frederick M, Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Pander JP, et al. ACCESS Group HLA and environmental interactions in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2008;25:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li J, Yang J, Levin AM, Montgomery CG, Datta I, Trudeau S, et al. Efficient generalized least squares method for mixed population and family-based samples in genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol . 2014;38:430–438. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen Y, Adrianto I, Ianuzzi MC, Garman L, Montgomery CG, Rybicki BA, et al. Extended methods for gene-environment-wide interaction scans in studies of admixed individuals with varying degrees of relationships. Genet Epidemiol . 2019;43:414–426. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, Kullman GJ, Henneberger PK, London SJ, Alavanja MC, et al. Pesticides and other agricultural factors associated with self-reported farmer’s lung among farm residents in the Agricultural Health Study. Occup Environ Med . 2007;64:334–341. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.028480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Henneberger PK, Liang X, London SJ, Umbach DM, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Exacerbation of symptoms in agricultural pesticide applicators with asthma. Int Arch Occup Environ Health . 2014;87:423–432. doi: 10.1007/s00420-013-0881-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ye M, Beach J, Martin JW, Senthilselvan A. Association between lung function in adults and plasma DDT and DDE levels: results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Environ Health Perspect . 2015;123:422–427. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hernández AF, Casado I, Pena G, Gil F, Villanueva E, Pla A. Low level of exposure to pesticides leads to lung dysfunction in occupationally exposed subjects. Inhal Toxicol . 2008;20:839–849. doi: 10.1080/08958370801905524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Smoking, obesity and risk of sarcoidosis: a population-based nested case-control study. Respir Med . 2016;120:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Douglas JG, Middleton WG, Gaddie J, Petrie GR, Choo-Kang YF, Prescott RJ, et al. Sarcoidosis: a disorder commoner in non-smokers? Thorax . 1986;41:787–791. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.10.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Exley C, Begum A, Woolley MP, Bloor RN. Aluminum in tobacco and cannabis and smoking-related disease. Am J Med . 2006;119:276.e9-11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pappas RS, Watson CH, Valentin-Blasini L. Aluminum in tobacco products available in the United States. J Anal Toxicol . 2018;42:637–641. doi: 10.1093/jat/bky034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Crouser ED, Smith RM, Culver DA, Julian MW, Martin K, Baran J, et al. A pilot randomized trial of transdermal nicotine for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest . 2021;160:1340–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harper LJ, Love G, Singh R, Smith A, Culver DA, Thornton JD. Barriers to care among patients with sarcoidosis: a qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2021;18:1832–1838. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202011-1467OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rabin DL, Thompson B, Brown KM, Judson MA, Huang X, Lackland DT, et al. Sarcoidosis: social predictors of severity at presentation. Eur Respir J . 2004;24:601–608. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00070503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]