In 1747, Andreas Sigismund Marggraf was in dire straits: His stock of sugar cane, from which he extracted saccharose in his pharmacy (located until 1945 next to Berlin’s City Hall) to sell as a luxury commodity to Berlin’s upper class, was dwindling as the Silesian wars threatened his supply routes. As a substitute, he experimented with local plants, finally succeeding in extracting sugar from beets—and thus, for the first time, isolating glucose.

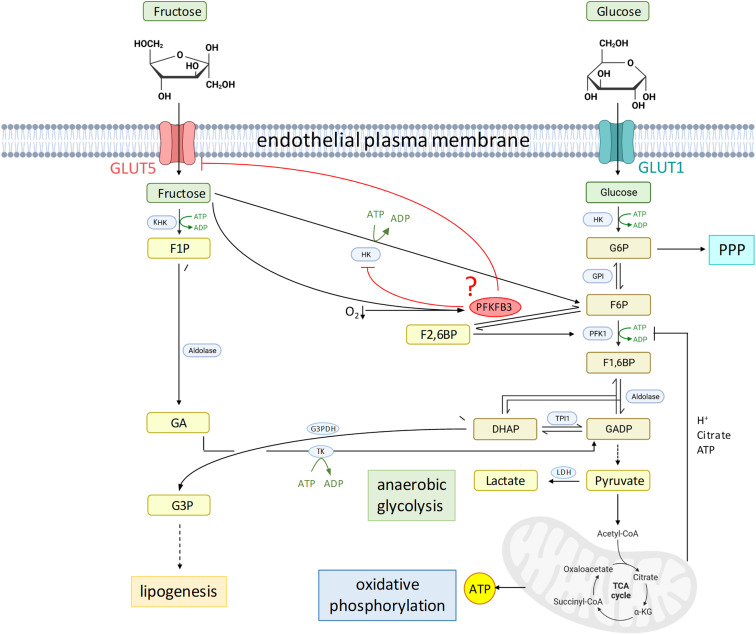

Glucose is, of course, the main (and, in some cases, exclusive) fuel for our cells, generating essential energy by means of aerobic or anaerobic glycolysis. This also applies to endothelial cells, which, under resting conditions, generate 85% of their ATP by converting glucose to lactate, seemingly avoiding oxidative metabolism despite their proximity to oxygen in the blood (1). How endothelial cells adapt their metabolism under stress, however, is less clear. In extreme environments, some cells (2) and entire organisms (3) manage to utilize fructose to facilitate rapid growth or survival. In these cases, fructose is taken up by means of the fructose transporter GLUT5 and utilized for glycolysis by one of two pathways (Figure 1): Either fructose can be phosphorylated similarly to glucose at C6 by hexokinase (HK) and fed into the classic glycolytic pathway, or it can be phosphorylated at C1 by ketohexokinase yielding fructose-1-phosphate, which can be directly metabolized into trioses, thus bypassing the negative-feedback regulation of the classic glycolysis pathway through inhibition of 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase (PFK-1) by citrate, protons, and ATP.

Figure 1.

Proposed inhibition of endothelial fructose utilization by PFKFB3. Left: fructose metabolism. Right: glucose metabolism. Created with BioRender.com. α-KG = α-ketoglutarate; CoA = coenzyme A; DHAP = dihydroxyacetone phosphate; F1P = fructose-1-phosphate; F1,6BP = fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; F2,6BP = fructose-2,6-bisphosphate; F6P = fructose-6-phosphate; G3P = glycerol-3-phosphate; G3PDH = glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; G6P = glucose-6-phosphate; GA = glyceraldehyde; GADP = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; GPI = glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; HK = hexokinase; KHK = ketohexokinase; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; PFK = phosphofructokinase; PFKFB3 = 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; PPP = pentose phosphate pathway; TCA = tricarboxylic acid; TK = triose kinase; TPI1 = triosephosphate isomerase 1.

In this issue of the Journal, Lee and coworkers (pp. 340–354) describe their exploration regarding whether pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) may also use fructose for glycolysis (4). When PMVECs were kept in high-fructose media, ATP production and cell proliferation were markedly reduced as compared with high glucose, and the extracellular acidification rate and lactate accumulation were negligible, indicating that PMVECs were unable to utilize fructose as an equivalent source for glycolysis. An additional challenge by hypoxia resulted in a high rate of cell death in PMVECs in fructose yet not in glucose. This apparent inability to utilize fructose is in line with extremely low PMVEC transcript levels for ketohexokinase which is predominantly expressed in liver, kidney, and gut. But why don’t PMVECs utilize HK, which is expressed at functional levels in endothelial cells (1), to channel fructose into the glycolytic pathway?

Lee and colleagues demonstrate that, in response to fructose, PMVECs upregulate 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), a glycolytic enzyme that converts fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, which serves as an allosteric activator of PFK-1, counteracting the negative-feedback inhibition by glycolysis products (Figure 1). PFKFB3 is also upregulated by hypoxia in a hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1)–dependent manner (5); hence, combined exposure to fructose and hypoxia will result in a surge of PFKFB3 expression. Using functional and biochemical assays in combination with metabolomic analyses and in vivo experiments in inducible endothelial-specific PFKFB3-deficient mice, the authors identify here a novel role for PFKFB3 as blocker of fructose utilization for glycolysis. This was evident in PFKFB3-deficient PMVECs, which, relative to wild-type cells, restored ATP production and survival in hypoxic conditions and increased lactate accumulation and extracellular acidification, all glycolytic intermediates, as well as intermediates of the tricarboxylic cycle and pentose phosphate pathway in high-fructose conditions. The fact that PFKFB3-deficient cells can utilize fructose points to a novel role of PFKFB3 not only as promoter of glucose-mediated glycolysis but also in parallel as inhibitor of fructose-mediated glycolysis. The latter effect seemingly relates to the utilization of fructose through HK, as extracellular lactate accumulation in high-fructose, PFKFB3-deficient PMVECs was blocked by HK inhibition. The authors convincingly conclude that PFKFB3 acts as a molecular switch in control of substrate metabolism by glycolysis.

But how does PFKFB3 inhibit fructose metabolism? PFKFB3 may—directly or indirectly—inhibit HK. In this case, PFKFB3-deficient cells would also increase glucose-mediated glycolysis, yet this effect would be counteracted by reduced PFK-1 activity. PFKFB3 deficiency had little impact on glycosidic intermediates in glucose media, but it increased pentose phosphate pathway flux (which branches off the glycosidic pathway upstream of PFK-1) while reducing glucose conversion to lactate. This may point to HK inhibition by PFKFB3, and PFKFB3 may serve as a switch between glucose and fructose glycolysis but also between glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. Alternatively, PFKFB3 may reduce substrate availability for fructose metabolism. By RNA sequencing, Lee and colleagues show that PFKFB3 deletion may increase GLUT5, implying that PFKFB3, itself regulated by fructose, may counteract fructose uptake by downregulating its transporter by means of negative feedback (4). However, the conclusion that, because of GLUT5 downregulation, fructose uptake in wild-type PMVECs is negligible also falls short, as pointed out by the authors’ interpretation of their Seahorse assays: Although PMVECs were unable to use fructose for glycolysis, they sustained oxidative phosphorylation independently of PFKFB3 in fructose media at normoxia. As such, the exact molecular nature of PFKFB3’s role as a glycosidic switch remains to be elucidated.

Lee and colleagues show that minimal fructose utilization for glycolysis is not restricted to PMVECs but is similarly evident in other endothelial cells (4). Yet why, from an evolutionary perspective, should endothelial cells not utilize fructose for glycolysis? Fructose metabolism is a common evolutionary pathway of survival, providing adequate fuel even when oxygen availability is limited (6). This strategy has been exploited by the naked mole-rat, which can survive unharmed for 18 minutes in complete anoxia by switching to anaerobic metabolism fueled by fructose (3). Why do endothelial cells not make use of a similar strategy? The answer remains speculative, but two possibilities come to mind: First, with PFKFB3 boosting glucose metabolism while inhibiting fructose-mediated glycolysis, endothelial cells may have “opted” to put all their eggs in one basket and, given their privileged access to circulating blood sugars, rely exclusively on sufficient glucose supply. Alternatively, the lack of endothelial fructose metabolism may be beneficial. Dietary fructose—now excessively available in refined sugar and high-fructose corn syrup—increases cardiovascular risk by promoting endothelial dysfunction (1). The extent to which such effects are attributable to direct uptake and metabolism of fructose by endothelial cells is unclear. Yet, with PFKFB3 inhibitors under development for cancer treatment—partially based on their antiangiogenic effect on endothelial cells—(7), we should keep in mind that PFKFB3’s role as “physiologic brake” on endothelial fructose utilization may serve homeostatic functions that we simply do not yet understand. There may be a reason why endothelial cells do not like fructose but rather prefer to die in hypoxia. It almost seems that Johann Sebastian Bach, a decade before the discovery of glucose, had a premonition of this scenario when he titled his sacred song BWV 478 “Come, Sweet Death.”

Footnotes

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2023-0195ED on June 22, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Li X, Kumar A, Carmeliet P. Metabolic pathways fueling the endothelial cell drive. Annu Rev Physiol . 2019;81:483–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J, Dong C, Wu J, Liu D, Luo Q, Jin X. Fructose utilization enhanced by GLUT5 promotes lung cancer cell migration via activating glycolysis/AKT pathway. Clin Transl Oncol. 2023;25:1080–1090. doi: 10.1007/s12094-022-03015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park TJ, Reznick J, Peterson BL, Blass G, Omerbašić D, Bennett NC, et al. Fructose-driven glycolysis supports anoxia resistance in the naked mole-rat. Science . 2017;356:307–311. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee JY, Stevens RP, Pastukh VV, Pastukh VM, Kozhukhar N, Alexeyev MF, et al. PFKFB3 inhibits fructose metabolism in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2023;69:340–354. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0443OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minchenko A, Leshchinsky I, Opentanova I, Sang N, Srinivas V, Armstead V, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-mediated expression of the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3 (PFKFB3) gene. Its possible role in the Warburg effect. J Biol Chem . 2002;277:6183–6187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110978200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson RJ, Stenvinkel P, Andrews P, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Nakagawa T, Gaucher E, et al. Fructose metabolism as a common evolutionary pathway of survival associated with climate change, food shortage and droughts. J Intern Med . 2020;287:252–262. doi: 10.1111/joim.12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang Q, Hou P. Targeting PFKFB3 in the endothelium for cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med . 2017;23:197–200. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]