Abstract

The VanC phenotype, as found in Enterococcus gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, and E. flavescens, is characterized by intrinsic low-level resistance to vancomycin. The nucleotide sequences of the vanC-1 gene in E. gallinarum, the vanC-2 gene in E. casseliflavus, and the vanC-3 gene in E. flavescens have been reported, although there is some disagreement as to whether E. flavescens is a legitimate enterococcal species. Previous attempts to differentiate the vanC-2 and vanC-3 genes by PCR analysis have been unsuccessful. The purpose of the present study was to detect and differentiate the three vanC determinants and examine the distribution of these genes in a collection of both typical and atypical enterococci. The 796-bp vanC-1 PCR product was amplified only from E. gallinarum isolates. As expected, due to the extensive homology in the vanC-2 and vanC-3 gene sequences, all of the E. casseliflavus and E. casseliflavus/flavescens isolates produced the 484-bp vanC-2 PCR product, although the E. gallinarum isolates were negative. Only the E. casseliflavus/flavescens isolates produced the 224-bp vanC-3 product. Using the three sets of primers, we were able to detect and distinguish the vanC-1, vanC-2, and vanC-3 genes from both typical and atypical enterococci strains. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests and analysis of genomic DNA by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis were also performed, but the results indicated that they were not able to distinguish among strains possessing the three vanC genotypes.

The VanC phenotype, as found in Enterococcus gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, and E. flavescens, is characterized by intrinsic low-level resistance to vancomycin. The nucleotide sequences of the vanC-1 gene in E. gallinarum, the vanC-2 gene in E. casseliflavus, and the vanC-3 gene in E. flavescens have been reported, although there is some disagreement as to whether E. flavescens is a legitimate enterococcal species (3, 7, 10, 18). Descheemaeker et al. were unable to discriminate between E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or oligonucleotide D11344-primed PCR (3). Previous attempts to differentiate the vanC-2 and vanC-3 genes by PCR analysis have also been unsuccessful (4, 11). Although these organisms are not as clinically significant as the other members of the group II enterococci, i.e., E. faecalis and E. faecium, clusters of infection have previously been reported (5, 6). In 1991, Pompei et al. reported four strains of yellow-pigmented enterococci resembling E. casseliflavus, all of which were isolated from surgical patients (13). These four strains were further characterized by DNA-DNA hybridization and biochemical tests, and the differences were considered significant enough for the strains to be designated a new species, E. flavescens, with the type strain CCM 439 (12). E. casseliflavus was incriminated in a series of bloodstream infections in a hemodialysis unit over an 8-month period (9). Pigment production and the motility test can usually differentiate E. faecium from the three enterococcal species carrying vanC genes, while acid production from ribose is the only biochemical test capable of differentiating E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens. The variable nature of these characteristics, however, complicates the proper identification of these species necessary for epidemiologic studies (5, 6). The recent report of vanC-1-containing E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates also emphasizes the importance of differentiation of the vanC genes for epidemiologic studies (11).

The purposes of this study were (i) to detect and differentiate the vanC genotypes, if possible, and (ii) to study the distribution of the respective vanC genes among a collection of typical and atypical enterococcal strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

The 30 isolates of enterococci with the VanC phenotype characterized in this study, including 21 E. casseliflavus or E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates and 9 E. gallinarum isolates, are listed in Table 1. All of the enterococcal isolates were identified at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention by standard methods (5, 6, 19). The control strains included E. faecalis A256 (vanA genotype [16]), V583 (vanB genotype [14]), and ATCC 19433 (type strain); E. faecium ATCC 19434 (type strain), and E. gallinarum VR-42 (vanC-1 genotype [2]). E. gallinarum SS-1228 (ATCC 49573 [type strain]) (vanC-1 genotype), E. casseliflavus SS-1229 (ATCC 25788 [type strain]) (vanC-2 genotype [10]), and E. flavescens SS-1317 (CCM-439 [type strain]) (vanC-3 genotype [10]) strains were included in the study. E. flavescens SS-1317 (CCM-439), SS-1318 (CCM-440), and SS-1319 (CCM-441) were received from Raffaello Pompei, Rome, Italy (12, 13).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics, antimicrobial susceptibility, and vanC PCR results of typical and atypical Enterococcus species of VanC phenotypea

| Isolate | Source or reference | Identification | ARG | MOT | PIG | RIBb | VM | TEI | PEN | AM | RIF | CIP | vanC PCRc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS-1229 | ATCC 25788 | E. casseliflavus | + | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 1 | 2 |

| SS-938 | ATCC 25789 | E. casseliflavus | + | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | >4 | 2 | 2 |

| SS-1317 | CCM 439 | “E. flavescens”d | +de | + | + | − | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 1 | 2/3 |

| SS-1318 | CCM 440 | “E. flavescens”d | +d | + | + | − | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | 2/3 |

| SS-1319 | CCM 441 | “E. flavescens”d | +d | + | + | − | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | 2/3 |

| SS-1341 | ATCC 12755 | E. casseliflavus | +d | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 1112-75 | Blood | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | +d | + | + | +d | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 1119-75 | Blood | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | − | + | + | +d | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 1486-76 | Feces | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | +d | + | + | +d | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 1487-76 | Feces | E. casseliflavus | +d | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | >4 | 1 | 2 |

| 318-83 | Urine | E. casseliflavus | + | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | >4 | 2 | 2 |

| 1516-83 | Wound | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | +d | + | + | +d | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 2/3 |

| 1853-91 | Blood | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | − | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 361-92 | Blood | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | − | + | + | − | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >4 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 1673-93 | Blood | E. casseliflavus | − | − | − | + | 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 1703-93 | Blood | E. casseliflavus | − | − | − | + | 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 237-94 | Abscess | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | − | + | + | − | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | ≤1 | 1 | 2/3 |

| 1316-94 | Blood | E. casseliflavus | − | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 1319-94 | Blood | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | − | + | + | + | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 1320-94 | Blood | E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens | − | + | + | + | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ≤1 | 2 | 2/3 |

| 1325-94 | Unknown | E. casseliflavus | − | + | + | + | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| SS-1228 | ATCC 49573 | E. gallinarum | + | + | − | + | 8 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1362-91 | CSF | E. gallinarum | − | + | − | + | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ≤1 | 2 | 1 |

| 1475-91 | CSF | E. gallinarum | − | + | − | + | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | ≤1 | 2 | 1 |

| 616-93 | Urine | E. gallinarum | + | − | − | + | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | >4 | 8 | 1 |

| 447-94 | Blood | E. gallinarum | − | + | − | + | 4 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | ≤1 | 4 | 1 |

| 2628-95 | Unknown | E. gallinarum | +d | − | − | + | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | ≤1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2629-95 | Unknown | E. gallinarum | +d | − | − | + | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | ≤1 | 2 | 1 |

| 2630-95 | Unknown | E. gallinarum | +d | + | − | + | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | >4 | 1 | 1 |

| 2631-95 | Unknown | E. gallinarum | +d | + | − | + | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ≤1 | 2 | 1 |

| Control strains | |||||||||||||

| SS-1273 | ATCC 19433 | E. faecalis | + | − | − | + | ≤0.5 | ≤0.25 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | − |

| SS-1274 | ATCC 19434 | E. faecium | + | − | − | + | ≤0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | >4 | 8 | − |

| VR-42 | 2 | E. gallinarum (vanC-1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 | ≤0.5 | 1 | ND | ≤1 | 2 | 1 |

| A256 | 16 | E. faecalis (vanA) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 512 | 128 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | − |

| V583 | 14 | E. faecalis (vanB-1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 128 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ≤0.5 | − |

ARG, arginine; MOT, motility; PIG, pigment; RIB, ribose; VM, vancomycin; TEI, teicoplanin; PEN, penicillin; AM, ampicillin; RIF, rifampin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; ND, not done; NA, not applicable; +, positive reaction; −, negative reaction.

Results correspond to readings after 1 week of incubation. After observation for 7 days, only five strains remained negative for ribose. After 1 month, all strains were positive.

1, vanC-1 PCR product, or E. gallinarum; 2, vanC-2 product, or E. casseliflavus; and 2/3, vanC-2 and vanC-3 products, or E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens.

This strain was originally described by Pompeii et al. (12) as E. flavescens, but DNA-DNA hybridization results indicated they should be designated E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens. Now known as ATCC 49996, ATCC 49997, and ATCC 49998, respectively.

+d corresponds to a positive reaction and is detected only after at least 48 h of incubation.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

All isolates were tested by the broth microdilution method as described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (8) with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). The antimicrobial agents tested were ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, penicillin, rifampin, streptomycin, teicoplanin, and vancomycin. E. faecalis ATCC 29212 was the quality control strain used in the susceptibility testing.

PCR amplification of antimicrobial resistance genes.

The vanC genes that encode intrinsic low-level glycopeptide resistance in the enterococci were amplified by PCR with oligonucleotide primers selected from published sequences (4, 7, 10) with the assistance of the OLIGO software (National Biosciences, Hamel, Maine). The PCR reaction mix and conditions for amplification of the 796-bp vanC-1 gene product of E. gallinarum (2) and the 484-bp vanC-2 product of E. casseliflavus (15) have been described previously. The primers used for detection of the above genes were (5′→3′) (+) GAA AGA CAA CAG GAA GAC CGC and (−) ATC GCA TCA CAA GCA CCA ATC for vanC-1 (2) and (+) CGG GGA AGA TGG CAG TAT and (−) CGC AGG GAC GGT GAT TTT for vanC-2 (15).

The novel primers selected for amplification of the 224-bp vanC-3 gene product of E. flavescens were (5′→3′) (+) GCC TTT ACT TAT TGT TCC and (−) GCT TGT TCT TTG ACC TTA. For amplification of the vanC-3 gene, two to three bacterial colonies were suspended in 100 μl of sterile deionized water, and 2 μl of the suspension was added to the reaction mix containing 1× PCR buffer II, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP), 0.5 μM each primer, and 2.5 U of native Taq DNA polymerase (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). A Perkin-Elmer Cetus 9600 DNA thermocycler was programmed as described previously (2, 15).

Analysis of genomic DNA restriction patterns by PFGE.

The isolates were grown in Trypticase soy broth (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) overnight at 37°C with shaking. A modification of the procedure described by Smith and Cantor (17) was used for preparation of the agarose plugs. Briefly, the pellet from 300 μl of broth was resuspended in 300 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), mixed with an equal volume of 1.8% agarose (65 to 68°C; Bio-Rad Chromosomal Grade Agarose; Bio-Rad Chemical Co., Hercules, Calif.) in TE buffer, and poured into a plug mold. Mutanolysin (20 U/ml), instead of lysozyme, and 1 to 2 μg of RNase per ml was added to the EC lysis buffer (6 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA [pH 7.5], 0.5% Brij-58, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% Sarkosyl) used for treatment of the plugs overnight at 37°C. This solution was replaced by ESP solution (0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% Sarkosyl, and 1 mg of proteinase K per ml), and the plugs were incubated overnight at 50°C with gentle shaking. The plugs were washed with TE buffer and then stored at 4°C in TE buffer until needed. After digestion with 20 U of SmaI (New England BioLabs, Bedford, Maine), the plugs were placed in the wells of a 1% FastLane agarose (FMC BioProducts, Bedford, Maine) in 0.5× TBE and were electrophoresed at 200 V with a 0.1-s→20-s pulse time for 20 h at 14°C in the Bio-Rad CHEF-DRII system. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide, the restricted DNA was visualized with UV light, and the images were photographed with Polaroid type 55 film (Polaroid Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.) or were saved with the Foto Analyst Archiver System (Fotodyne, Inc., Hartland, Wis.) to floppy disks. The data were analyzed, and a dendrogram was generated with the Advanced Quantifier 1-D Match version 2.1 for Windows software (BioImage, Ann Arbor, Mich.).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to detect and differentiate the three vanC determinants and to examine the distribution of these genes in a collection of both typical and atypical enterococci. The biochemical characteristics and identification results of the typical and atypical VanC enterococci are given in Table 1. Although members of the group II enterococci with VanC phenotypes normally are arginine positive, motile, pigmented (except for E. gallinarum), and ribose positive (except for E. flavescens), the collection of strains selected for the present study included strains with variable results in these reactions that would, in most cases, prevent their proper identification. Precise identification of such strains was previously obtained by using analysis of whole-cell protein profiles and DNA-DNA reassociation experiments (18, 19).

Phenotypically, E. gallinarum is distinguished from the E. faecium, E. casseliflavus, and E. flavescens strains by its motility and lack of pigmentation (5, 6). However, three of the E. gallinarum strains included in our study were nonmotile, and two E. casseliflavus strains were nonmotile and nonpigmented. On the other hand, E. flavescens has been differentiated from E. casseliflavus by its lack of acid production from ribose. Five of the E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates included in the present study were negative for acid production from ribose after conventional incubation for 7 days, suggesting that they were E. flavescens. When the period of incubation was extended to 1 month, all were positive for acid production from ribose, thus eliminating the only phenotypic species distinction. Atypical isolates, such as strains 1673-93 and 1703-93, as well as 616-93, 2628-95, and 2629-95, would appear to be E. faecium by conventional tests, because they are nonmotile and nonpigmented, but PCR with the F1 and F2 primers as described by Dutka-Malen et al. (4) failed to amplify the 550-bp ddlE. faecium gene product in strains 1673-93 and 1703-93, suggesting that they are not E. faecium. Such strains would not be adequately identified on the basis of phenotypic characteristics alone but could be identified only by additional tests such as acidification of methyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (MGP) and susceptibility to efrotomycin as recently proposed (1).

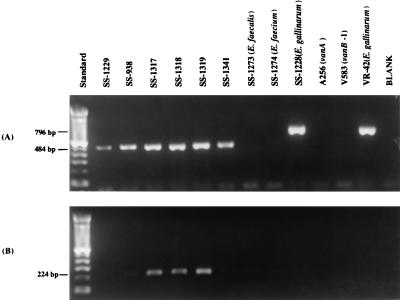

The 796-bp vanC-1 PCR product was amplified only from the E. gallinarum isolates and not from the E. casseliflavus or E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). As expected, due to the extensive homology (98.3%) shared in the vanC-2 and vanC-3 gene sequences, all of the E. casseliflavus or E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates produced the 484-bp vanC-2 PCR product; all E. gallinarum isolates were negative (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). Only the E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates produced the 224-bp vanC-3 product (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). Organisms yielding a vanC-1 gene product were reported as E. gallinarum, those yielding the vanC-2 product only were reported as E. casseliflavus, and those yielding both the vanC-2 and the vanC-3 products were reported as E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens.

FIG. 1.

Amplification of the vanC-1, vanC-2, and vanC-3 enterococcal genes by PCR. The standard in lane 1 is the 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). (A) vanC-1 (796-bp) and vanC-2 (484-bp) products amplified from selected study and control isolates with vanC-1 and vanC-2 primers in the reaction mix. Lanes 2 to 7 contain E. casseliflavus and E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens strains, and A256 and V583 are E. faecalis strains. (B) The vanC-3 (224-bp) products amplified from E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens strains are seen in lanes 4 to 6.

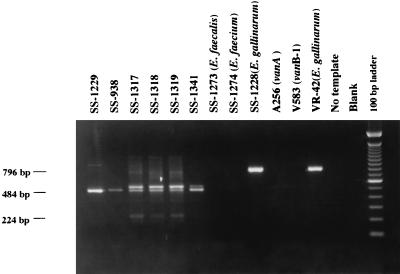

We also varied the concentrations of the primers in our multiplex PCR mixture containing the vanC-1 (0.1 μM), vanC-2 (0.1 μM), and vanC-3 (0.2 μM) primers in an attempt to eliminate the production of the vanC-2 product by the vanC-3-containing isolates (Fig. 2). We were not successful in eliminating the product, but only the vanC-3 isolates produced both the 484-bp (vanC-2) and the 224-bp (vanC-3) products. In the multiplex PCR, a 525-bp product was also amplified with both the vanC-2 and vanC-3 genes resulting from the combination of the vanC2(+) and vanC3(−) primers. The 525-bp product appeared to predominate in isolates with the vanC-3 gene, while the 484-bp product predominated with the vanC-2 gene. Only the E. gallinarum (vanC-1) isolate produced the expected 796-bp product.

FIG. 2.

Multiplex PCR of the vanC genes of enterococcal strains with the VanC phenotype. The reaction mix contained the vanC-1, vanC-2, and vanC-3 primers for amplification of the respective genes. Lanes 1 to 6, E. casseliflavus and E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates; lanes 3 to 5, the 224-bp vanC-3 product specific for E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates. Also, the 525-bp product that appears to be more prominent in E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates is seen. The 796-bp vanC-1 gene product amplified in E. gallinarum strains is in lanes 10 and 12. The molecular size standard is the 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco/BRL Life Technologies, Inc.).

The MICs for the VanC study isolates ranged from 2 to 8 μg/ml for vancomycin; most E. gallinarum isolates were intermediate (8 μg/ml), and all were susceptible to teicoplanin and did not show high-level resistance to gentamicin or streptomycin (Table 1). None of the antimicrobials tested distinguished among the species.

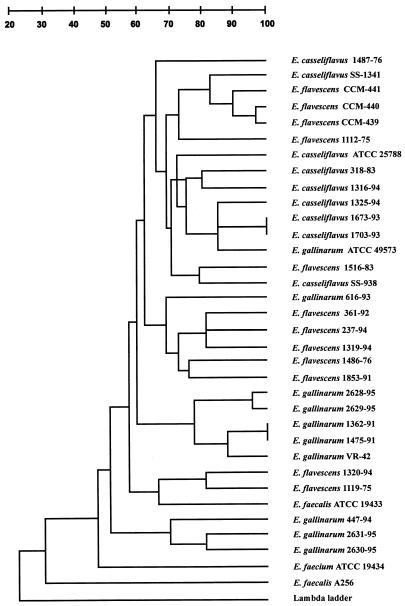

As seen in the dendrogram (Fig. 3), PFGE was not useful for differentiating the E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens isolates. In all E. gallinarum strains except for SS-1228 (ATCC 49573 [type strain]) and 616-93, only smaller molecular fragments were seen (<150 kb) in the PFGE patterns.

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram derived from analysis of the PFGE patterns of SmaI-digested genomic DNA of enterococcal strains with the VanC phenotype. E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens strains are labeled E. flavescens in the figure because of space limitations.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and PFGE were not able to distinguish among strains possessing the three vanC gene genotypes. In contrast, the use of the three sets of PCR primers allowed us to detect and differentiate the vanC-1 (E. gallinarum), vanC-2 (E. casseliflavus), and vanC-3 (E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens) genes from typical and atypical enterococcal strains. In all of the isolates characterized as E. gallinarum, the 796-bp vanC-1 gene product was amplified. Of the 21 E. casseliflavus or E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens isolates, all were shown to carry the vanC-2 gene, and 10 of them also possessed the vanC-3 gene. Therefore, the presence of the vanC genes may indicate a marker of species identification, and their detection may be an adjunct tool to assist in the precise identification of atypical strains. In a recent investigation testing some of the strains included in the present study, E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens were found to be a single species, and the term E. casseliflavus was recommended to be retained as the species denomination (18, 19). Taking this into account and considering our results, the presence of vanC-3 genes in some of the E. casseliflavus strains indicates that strains possessing the vanC-3 gene may constitute genotypic variants of this species. According to our data, such variants seem to be more frequently associated with ribose-negative variants, including those with a delayed reaction, of E. casseliflavus, which were denominated E. casseliflavus-E. flavescens, since the scope of the present study would not allow us to speculate on the validity of the designation E. flavescens as a separate species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carvalho M D G S, Teixeira L M, Facklam R R. Use of tests for acidification of methyl-α-d-glucopyranoside and susceptibility to efrotomycin for differentiation of strains of Enterococcus and some related genera. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1584–1587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1584-1587.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark N C, Cooksey R C, Hill B C, Swenson J M, Tenover F C. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Descheemaeker P, Lammens C, Pot B, Vandamme P, Goossens H. Evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of large genomic DNA fragments for identification of enterococci important in human medicine. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:555–561. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:24–27. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.24-27.1995. . (Erratum, 33:1434.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Facklam R R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Facklam R R, Sahm D F. Enterococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leclercq R, Dutka-Malen S, Duval J, Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance gene vanC is specific to Enterococcus gallinarum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2005–2008. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Approved standard M7-A4. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 4th ed. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nauschuetz W F, Trevino S B, Harrison L S, Longfield R N, Fletcher L, Wortham W G. Enterococcus casseliflavus as an agent of nosocomial bloodstream infections. Med Microbiol Lett. 1993;2:102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarro F, Courvalin P. Analysis of genes encoding d-alanine-d-alanine ligase-related enzymes in Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel R, Uhl J R, Kohner P, Hopkins M K, Cockerill F R., III Multiplex PCR detection of vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2/3 genes in enterococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:703–707. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.703-707.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pompei R, Berlutti F, Thaller M C, Ingianni A, Cortis G, Dainelli B. Enterococcus flavescens sp. nov., a new species of enterococci of clinical origin. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:365–369. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pompei R, Lampis G, Berlutti F, Thaller M C. Characterization of yellow-pigmented enterococci from severe human infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2884–2886. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2884-2886.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahm D F, Kissinger J, Gilmore M S, Murray P R, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satake S, Clark N, Rimland D, Nolte F S, Tenover F C. Detection of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in fecal samples by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2325–2330. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2325-2330.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shlaes D M, Bouvet A, Devine C, Shlaes J H, Al-Obeid S, Williamson R. Inducible, transferable resistance to vancomycin in Enterococcus faecalis A256. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:198–203. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith C L, Cantor C R. Purification, specific fragmentation, and separation of large DNA molecules. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:449–467. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teixeira L M, Carvalho M G S, Merquior V L C, Steigerwalt A G, Teixeira M G M, Brenner D J, Facklam R R. Recent approaches on the taxonomy of the enterococci and some related microorganisms. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;418:397–400. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teixeira, L. M., et al. Unpublished data.