Synopsis

Understanding the biology of blood-feeding arthropods is critical to managing them as vectors of etiological agents. Circadian rhythms act in the regulation of behavioral and physiological aspects such as blood feeding, immunity, and reproduction. However, the impact of sleep on these processes has been largely ignored in blood-feeding arthropods, but recent studies in mosquitoes show that sleep-like states directly impact host landing and blood feeding. Our focus in this review is on discussing the relationship between sleep and circadian rhythms in blood-feeding arthropods along with how unique aspects such as blood gluttony and dormancy can impact sleep-like states. We highlight that sleep-like states are likely to have profound impacts on vector–host interactions but will vary between lineages even though few direct studies have been conducted. A myriad of factors, such as artificial light, could directly impact the time and levels of sleep in blood-feeding arthropods and their roles as vectors. Lastly, we discuss underlying factors that make sleep studies in blood-feeding arthropods difficult and how these can be bypassed. As sleep is a critical factor in the fitness of animal systems, a lack of focus on sleep in blood-feeding arthropods represents a significant oversight in understanding their behavior and its role in pathogen transmission.

Sleep, daily rhythms, and circadian biology

All living organisms are affected by the daily oscillations in environmental factors (such as light and temperature) that occur as the Earth rotates on its axis approximately every 24 h (Brody 2020; Kim et al. 2020). The exception may be specific species that live in constant conditions for extended periods, such as those that permanently reside underground and in the deep sea, but most still have other factors that induce rhythmic behaviors. As a result, changes in organismal behavior and physiology directly induced or controlled by external cues are called daily (or diel) rhythms (Tataroglu and Emery 2015; Patke et al. 2020). However, daily rhythms that occur in anticipation of external cues but persist in constant conditions are called circadian rhythms (Patke et al. 2020; Prior et al. 2020). Circadian rhythms, controlled by autonomous clocks that are entrained by environmental cues, serve essential benefits in living organisms, including energy conservation, reducing competition for resources, regulation of biochemical and physiological mechanisms, and mating coordination (Nation 2022). In arthropods (mostly based on studies on insects), circadian rhythms influence several processes such as the hormonal regulation of molting and metamorphosis (Ampleford and Steel 1982; Lazzari and Insausti 2008), social organization in honeybees (Bloch 2010), and reproductive functions, including sperm release, mating time, and egg laying (Bebas et al. 2001; Sakai and Ishida 2001; Beaver et al. 2002). In addition to their influences on the aforementioned processes, circadian rhythms regulate the sleep process, by defining the time when sleep is most likely to occur in multiple arthropods (Dubowy and Sehgal 2017).

Sleep is an evolutionarily conserved phenomenon that has been described in different arthropods, including moths (Andersen 1968), cockroaches (Tobler 1983), bees (Kaiser and Steiner-Kaiser 1983; Kaiser 1988, 1995), crayfish (Ramón et al. 2004), scorpions (Tobler and Stalder 1988), spiders (Rößler et al. 2022), and the versatile model organism Drosophila melanogaster (Hendricks et al. 2000; Shaw et al. 2000). Based on available methods, sleep-like states in nonmammalian systems (like arthropods) are characterized mainly using behavioral or electrophysiological criteria (Keene and Duboue 2018). In general, there is a strong correlation between sleep-like states defined by both criteria in animals, especially in invertebrates, that is, sleep-associated behavioral changes co-occur with sleep-associated neurological changes (Allada and Siegel 2008). Behavioral identifiers of sleep in animals that have been observed in the arthropods already mentioned include the adoption of species-specific postures, prolonged immobility (reversible upon stimulation), decreased response to external stimuli (i.e., increased arousal threshold), and a compensatory increase in sleep during recovery after a period of sleep deprivation (Keene and Duboue 2018). Unlike the measurements of the electroencephalogram to denote sleep in mammals, studies in invertebrates use local field potential (LFP) recordings as proxies for the electrophysiological correlates of sleep (Nitz et al. 2002; van Alphen et al. 2013). Recently, periodic bouts of retinal movements in the jumping spider, Evarcha arcuata, along with limb twitching and stereotyped leg curling behaviors were established as sleep-like states (Rößler et al. 2022). Comparative genomics is likely to be useful for examining underlying genes across diverse taxa that have been directly linked to sleep, providing an additional line of evidence in conjunction with behavioral or electrophysiological studies.

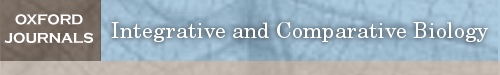

In D. melanogaster, individuals take up a prone position after moving away from a food source as they enter a sleep state. During the sleep period in these flies, the only movements observable are respiratory abdominal pumping, and minute but sporadic extension/retraction of the proboscis (Hendricks et al. 2000). Consolidated periods of immobility in the dark period (scotophase), characterized by an increased arousal threshold, are a feature of sleep in these insects, as reported in different studies (Shaw et al. 2000; Andretic and Shaw 2005). Importantly, these flies also show strong sleep rebound in the light phase (photophase) after sleep deprivation in the preceding night (Hendricks et al. 2000; Shaw et al. 2000). Electrophysiologically, a decrease in the levels of Ca2+ and LFPs in specific brain cells in Drosophila is associated with sleep-like states and, conversely, an increase in these signals correlates with wakefulness (Nitz et al. 2002; Bushey et al. 2015). In the last couple of decades, molecular studies using the Drosophila system not only have enriched our understanding of sleep in insects but have also been useful for practical human applications, especially in the area of sleep disorders and their treatments (Cirelli 2009; Allada et al. 2017). While the majority of sleep studies in arthropods are investigations carried out in nonhematophagous arthropods such as fruit flies, recently there has been an interest in evaluating sleep in blood-feeding arthropods, especially in mosquitoes (Fig. 1; Ajayi et al. 2020, 2022).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of sleep in mosquitoes and fruit flies. (A) Sleep phenotypes and parameters established in mosquitoes and fruit flies. Literature sources of established parameters can be found in Supplementary Table S1. (B) Differences in sleep profiles among three female mosquito and Drosophila species. Sleep profiles of the mosquito and Drosophila species were modified from Ajayi et al. (2022) and Mishra et al. (2023), respectively. White and dark horizontal bars represent photophase and scotophase, respectively. Created with BioRender.com, check online for colored version.

Blood-feeding arthropods, including mosquitoes, ticks, tsetse flies, and kissing bugs, are vectors of several pathogenic organisms responsible for diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, filariasis, babesiosis, typhus, Lyme disease, African trypanosomiasis, and Chagas disease (Mathison and Pritt 2014; Sonenshine and Stewart 2021). Diseases associated with blood-feeding arthropods have resulted in the collapse of armies or even entire civilizations (Busvine 1993; Sherman 2017), the mortality of millions of people, and significant morbidity among survivors (Alvar et al. 2020), and some that are not lethal have continued to occur at epidemic proportions in the last few years (Rosenberg et al. 2018). A recent report revealed that over half of the world’s population is at risk for arthropod-borne diseases, further confirming their medical and public health importance (World Health Organization 2020). Even those not in endemic areas for malaria and other prevalent diseases are potentially exposed to less prevalent vector-borne diseases, such as Japanese encephalitis and Powassan virus infection (Kemenesi and Bányai 2019; Quan et al. 2020). Furthermore, diseases that affect livestock are responsible for a significant reduction in their production, thereby impairing the nutritional needs of local human populations, especially those living in tropical and subtropical regions (Mullen and Durden 2009). As with other arthropods, the biology and physiology of blood-feeding arthropods are under the influence of biological rhythms that are regulated by a myriad of environmental factors.

Significant and consistent daily biological rhythms are experienced by blood-feeding arthropods (Clements 1999; Meireles-Filho and Kyriacou 2013). Kissing bugs are nocturnal insects that display two peaks of activity during the night: one at dusk to search for their host and one at dawn to seek shelter (Lazzari 1992; Lorenzo and Lazzari 1998, 1999). In tsetse flies and kissing bugs, these rhythms are correlated with daily rhythmic changes in their olfactory systems, showing increased sensitivity at specific times (Van der Goes van Naters et al. 1998; Barrozo et al. 2004; Rund, Bonar, et al. 2013a; Eilerts et al. 2018). Generally, sand flies are most active at dusk, but factors, including physiological state, environmental conditions, and host availability, can alter their activity patterns (Morrison et al. 1995; Meireles-Filho et al. 2006; Rivas et al. 2008). Indeed, one could expect blood-feeding arthropods to optimize their energy expenditure and increase their chance of success by being nocturnal to minimize their risk of desiccation, prevent UV damage from the Sun, and avoid day-active predators such as dragonflies, which rely on vision to locate their prey (Rund et al. 2016; Benoit and Vinauger 2022). However, the variation in activity patterns between different mosquito species in similar environments is a great example of how the vector’s behavior can be affected by nonenvironmental external factors, such as host presence (Clements 1999; Meireles-Filho and Kyriacou 2013). This is reflected in a range of physiological and sensory adaptations in response to time-specific activities. For example, several genes involved in mosquito visual pathways are rhythmically expressed, like rhodopsin levels, which increase at night in the nocturnal Anopheles gambiae (Moon et al. 2014) and decrease during the late afternoon and evening in the diurnal Aedes aegypti (Hu et al. 2012). Although hereditary, these activity patterns show some level of plasticity, and the insect’s physiological state plays a role in their activity patterns. For example, vectors tend to be less active, sometimes by up to 95%, after ingesting a blood meal (Rowland 1989; Meireles-Filho et al. 2006). Beyond these aspects of the vector’s biology, several other physiological and behavioral processes are rhythmically modulated in vectors, including vision, olfaction, mating, metabolism, locomotion, feeding (sugar and blood), biting, and oviposition (Ampleford and Davey 1989; Lazzari 1992; Lorenzo and Lazzari 1998; Rund et al. 2016).

Blood-feeding arthropods not only have to synchronize their clocks to match the environmental conditions but also need to synchronize their rhythms to match their hosts to optimize their chances of acquiring blood meals without getting killed during the attempt. In other words, the vectors’ internal clock times their sensory sensitivity and locomotor activity to moments of the day when the hosts are available and least defensive. This can turn into a complex and dynamic system since the hosts have their specific rhythms and activity profiles, which can vary significantly between individuals and can change based on multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Benoit and Vinauger 2022). When the hosts change their behavior, the vectors have to be able to adapt, either by shifting their behavior or by finding alternative hosts (Moiroux et al. 2012; Vinauger et al. 2018). For example, the use of bed nets to prevent mosquito access to humans during the night changes the time-specific availability of the hosts (Pates and Curtis 2005). In response, An. funestus, a mosquito that typically feeds during the night, started to host-seek earlier (in the evening) or later (in the early morning) to adapt to the modified host availability (Moiroux et al. 2014; Sougoufara et al. 2014). However, despite the clear epidemiological importance of vectors’ biological rhythms, there has been a surprising lack of focus on sleep in blood-feeding arthropods (Ajayi et al. 2020; Benoit and,Vinauger 2022).

Although circadian rhythms and sleep share a strong connection, there are fundamental differences between both processes. Circadian rhythms help to establish the period in a 24-h day when certain biological processes (including sleep) are optimum (showing high peaks of occurrence) in response to the cycling of environmental cues such as light (Dubowy and Sehgal 2017). These benefit living organisms as incompatible processes can be separated temporally, for example, photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus (Merrow et al. 2005). On the other hand, sleep establishes specific periods during the day when organisms have reduced movement, altered metabolic activity, and decreased response to environmental stimulation (Dubowy and Sehgal 2017; Keene and Duboue 2018). Since 1994, locomotor activity has been the assay of choice for circadian rhythms. This is also applicable for sleep quantification, except that the emphasis is on the inverse of activity by establishing a cutoff (period of inactivity) correlating with a reduced sensory response. Importantly, molecular studies in flies have also shown that these two processes can be separated. Mutations in the core clock genes in flies can still result in normal total sleep amounts (except that the sleep is now fragmented across both the photophase and scotophase), and flies can still exhibit robust circadian activity rhythms even if they carry mutations that lead to extremely reduced sleep (Hendricks et al. 2003; Dubowy and Sehgal 2017).

Why is sleep difficult to study in blood-feeding systems?

Circadian rhythms have been studied in multiple arthropod systems, which suggests that there are likely periods of increased sleep during either the day or the night for most, if not all, species. A major issue for sleep studies in blood-feeding arthropods is that the presence of a host is likely to alter sleep-like states, making direct and accurate evaluation difficult due to exposure to host cues emanating from the experimenter (Gibson and Torr 1999). These sleep disruptions are likely to occur due to variable periods of exposure to host cues, such as CO2, which can change naturally in lab settings. This could be more critical for species that sleep during the day such as Culex pipiens and An. stephensi (Veronesi et al. 2012; Rund et al. 2016; Ajayi et al. 2022), as scientists will be in the lab mostly during the photophase. To accomplish sleep studies in blood-feeding systems, arthropod vectors must be isolated from accidentally detecting their host by conducting experiments in incubators or buildings that do not experience frequent human movements, except those that can be tracked by the investigator. This does not only apply to the specific room where sleep studies are conducted, but significant daily variations in CO2 and other host volatiles can occur within indoor spaces of the entire building and could impact vector sleep patterns (Jung et al. 2015; Erlandson et al. 2019). Thus, sleep studies need to be conducted in nearly isolated areas to ensure outside factors do not interrupt this physiological state.

Another major issue is that some species spend extended periods with little or no activity, such as prolonged quiescence between blood meals for ticks and bed bugs (Usinger 1966; Needham and Teel 1991), which makes behavioral observations of sleep-like states based on the most common methodology (i.e., infrared-based activity monitoring) nearly impossible. There is also a major difference between blood-feeding systems before and after a meal (Benoit and Denlinger 2010), suggesting significant differences in sleep patterns with feeding status. Similarly, the internal homeostatic status of arthropods, whether starved or dehydrated, can have profound impacts on rest–activity patterns (Klowden 1986; Brady 1988; McCue et al. 2017; Hagan et al. 2018; Rosendale et al. 2019; Benoit et al. 2023), as such the physiological state needs to be accounted for in sleep studies on blood-feeding arthropods. These combined factors make assessing sleep in blood-feeding systems difficult, but not insurmountable.

Direct evidence and potential sleep-like states in blood-feeding arthropods

Although sleep studies are limited and difficult to assess in blood-feeding arthropods, evidence suggests that sleep-like states occur in many disease vectors, and circadian rhythm studies in others indicate that sleep-like states likely exist in most blood-feeding systems. Here, we give an overview of what is known about mosquitoes, tsetse flies, blood-feeding hemipterans, ticks, and other important species based on the combination of sleep studies and what can be inferred from circadian and daily rhythm profiles. Importantly, beyond the current studies in mosquitoes (Ajayi et al. 2020, 2022), few studies have directly examined sleep states in hematophagous arthropods, but likely sleep profiles can be inferred from behavioral aspects such as activity patterns. A summary of periods when sleep is most likely to occur in specific genera is shown in Table 1, which is based on known activity patterns, field collections, and observations.

Table 1.

Comparison of predominant sleep time across different blood-feeding arthropods.

| Order | Representative families | Genus | Common name | Blood-feeding stages | Predicted sleep time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ixodida | Ixodidae | Ixodes | Deer tick | J, M, F | Day |

| Dermacentor | American dog tick | J, M, F | Night | ||

| Argasidae | Argas | Fowl tick | J, M, F | Day | |

| Diptera | Culicidae | Aedes | Yellow fever mosquito | F | Night |

| Culex | House mosquito | F | Day | ||

| Anopheles | Malaria mosquito | F | Day | ||

| Ceratopogonidae | Bezzia | Biting midge | F | Unknown | |

| Glossinidae | Glossina | Tsetse fly | M, F | Night and midday | |

| Hippoboscidae | Pseudolynchia | Pigeon louse fly | M, F | Unknown | |

| Muscidae | Stomoxys | Stable fly | M, F | Night | |

| Nycteribiidae | Nycteribia | Bat fly | M, F | Unknown | |

| Psychodidae | Lutzomyia | Sand fly | F | Day | |

| Rhagionidae | Symphoromyia | Snipe fly | F | Unknown | |

| Simuliidae | Simulium | Black fly | F | Night | |

| Streblidae | Trichobius | Bat fly | M, F | Unknown | |

| Tabanidae | Chrysops | Deer fly | F | Night | |

| Hemiptera | Cimicidae | Cimex | Bed bug | J, M, F | Day |

| Polyctenidae | Hesperoctenes | Bat bug | J, M, F | Night | |

| Reduviidae | Triatoma | Kissing bug | J, M, F | Day | |

| Lepidoptera | Erebidae | Calyptra | Vampire moth | M | Day |

| Phthiraptera | Haematopinidae | Haematopinus | Sucking lice | J, M, F | Unknown |

| Hoplopleuridae | Hoplopleura | Armored lice | J, M, F | Unknown | |

| Linognathidae | Linognathus | Pale lice | J, M, F | Unknown | |

| Pediculidae | Pediculus | Body lice | J, M, F | Unknown | |

| Polyplacidae | Polyplax | Spiny rat lice | J, M, F | Unknown | |

| Pthiridae | Phthirus | Pubic lice | J, M, F | Day | |

| Siphonaptera | Ceratophyllidae | Ceratophyllus | Chicken flea | M, F | Unknown |

| Ctenophthalmidae | Rhadinopsylla | Rodent flea | M, F | Unknown | |

| Leptopsyllidae | Leptosylla | Mouse flea | M, F | Unknown | |

| Pulicidae | Ctenocephalides | Cat flea | M, F | Day |

Notes: J = juvenile; M = male; F = female. Predicted sleep time is defined as when consolidated periods of sleep are likely to occur, and this is based on a combination of activity profiles, daily field collections, and biting times except for studies on specific mosquito species. Literature sources related to this can be found within the specific section of the main text and in the condensed version of the table (Supplementary Table S2).

Following a blood meal, there is a general trend of reduced activity that is noted for most, if not all, hematophagous arthropods (Brady 1988; Rowland 1989; Meireles-Filho et al. 2006; Gentile et al. 2013; Traoré et al. 2021; Benoit and Vinauger 2022). During this period of blood digestion along with oogenesis for females, typical diel patterns of activity are suppressed or lacking. Once the individual has digested the blood and, in the case of females, completed oogenesis, activity levels return to prefeeding levels to allow for progeny deposition or a return to host-seeking. It is unknown if the reduced activity is increased sleep-like states. A reduction in response to external cues suggests that this could be a sleep-like state or could be due to other factors such as altered expression of chemosensation genes (Rinker et al. 2013; Duvall 2019; Latorre Estivalis et al. 2022). Likely, a combination of altered sleep states and shifted chemosensation could underlie the pre- and post-blood meal differences, but targeted studies are necessary for confirmation.

Mosquitoes

An early investigation revealed the resting postures of Ae. aegypti to be different from the body position during normal hovering flights and between flights (Haufe 1963). This was the first description of potential sleep-like states in mosquitoes; however, this study failed to consider these resting postures as actual periods of sleep. Recently, other observations have emerged to support the occurrence of sleep-like conditions in mosquitoes (Ajayi et al. 2020, 2022). The aforementioned unique resting posture of Ae. aegypti provides a distinction between periods of low activity (putative sleep) and high activity (active state) in Ae. aegypti. This sleep-like posture is characterized by lowered hind legs and changes in the orientation of the abdomen along the substrate/resting surface (Ajayi et al. 2020). Importantly, these periods (low and high activity) are under distinct circadian influences in multiple mosquito species (Rund et al. 2012, 2016), where high activity (biting times) and low activity (prolonged immobility) differ in arousal threshold, an important hallmark of sleep in animals (Keene and Duboue 2018). Orthologs of sleep-based genes reported in Drosophila have been identified in different mosquito species. These genes have functional roles in the sleep/wake cycles, metabolism of dopamine and octopamine, and neuronal signaling, highlighting potential critical roles in sleep (Ajayi et al. 2020).

Moreover, sleep deprivation induces sleep recovery in both day-active (Ae. aegypti) and night-active (An. stephensi) mosquitoes, consistent with observations in previously studied arthropods (Helfrich-Förster 2018; Ajayi et al. 2022; Benoit and Vinauger 2022). Blood-feeding propensity and host landing were suppressed during the light phase after night-time sleep deprivation in Ae. aegypti (Ajayi et al. 2022). These two indices evaluated here are an important consideration concerning disease transmission in mosquitoes and other blood-feeding arthropods, showing that there might be a potential link between sleep or its deprivation and disease transmission. In the same study, we identified differences in sleep patterns and amounts among three mosquito species, similar to differences reported in Drosophila studies (Ito and Awasaki 2022; Mishra et al. 2023). Other studies have shown sleep differences among multiple lines of the same species from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP), where several candidate genes associated with the variation in sleep have homologs identified in human sleep studies (Harbison et al. 2013; Serrano Negron et al. 2018). As a result, we predict similar observations in mosquitoes where strains from different populations or geographic lineages will show subtle variation in sleep, perhaps related to factors such as human preference that have been shown for other biological factors (Rose et al. 2020).

Tsetse flies

Sleep processes in tsetse flies have not been directly examined, but there has been considerable focus on understanding the circadian rhythms of tsetse flies that can be extrapolated to identify sleep periods (Brady 1988). Tsetse flies are unique compared to mosquitoes as these flies are obligate blood feeders and females deposit live larvae rather than eggs (Benoit et al. 2015; Attardo et al. 2019). The activity patterns for tsetse flies have a distinct U-shaped daily activity pattern with little to no activity during the night (Brady 1973, 1988; Brady and Crump 1978; Brady and Gibson 1983). Blood feeding depresses this U-shaped activity pattern, and low or high temperatures can prevent either the morning or evening activity peaks (Brady and Crump 1978; Crump and Brady 1979). These U-shaped daily activity patterns have also been noted for other host-finding parameters, such as olfactory response (Brady 1972, 1973, 1988) and host-biting rates in the field (Dean et al. 1969). Late in pregnancy, tsetse flies have a near-complete suppression of the U-shaped pattern, which returns to baseline a day after birth (Brady and Gibson 1983; Abdelkarim and Brady 1984).

Little is known about the molecular mechanism underlying tsetse fly circadian rhythms, but genomes for multiple tsetse fly species would make these studies feasible (International Glossina Genome Initiative 2014; Attardo et al. 2019). Consistent with the conservation of clock mechanisms in insects (Zhu et al. 2005; Tomioka and Matsumoto 2015), orthologs of the core circadian genes identified in Drosophila were found in tsetse flies, opening new research avenues in this direction. Based on sleep and activity patterns known in other insect systems (Helfrich-Förster 2018; Ajayi et al. 2022; Benoit and Vinauger 2022), tsetse flies likely sleep mostly at night and will have increased resting/sleep periods at midday between the morning and evening peaks in activity. The impact of sleep deprivation on tsetse fly biology is likely to be unique due to the critical roles of circadian activity in finding a host that provides blood as food and water along with how sleep reduction may impact their unique viviparous reproduction.

Blood-feeding hemipterans

Blood-feeding hemipterans, which include members of Cimicidae and Reduviidae (Lehane 2005; Thomas et al. 2020), are usually active at night (Guerenstein and Lazzari 2009; Benoit and Vinauger 2022). Importantly, there are blood-feeding hemipterans that commonly feed on nocturnal animals, such as the bat bugs Cimex adjunctus, that will likely be active during the day when their hosts (bats) are sleeping (Usinger 1966). Most likely, bed bugs are inactive and sleep during the day (except for day-active species that feed on nocturnal vertebrates) within shelters to prevent detections by their host and avoid predation (Miller et al. 2013). Similar to most other blood-feeding arthropods, the sleep patterns of triatomine bugs have yet to be examined, but postural changes associated with sleep are likely similar to those that have been found in other hemimetabolous species (Helfrich-Förster 2018). There is a significantly higher response to host cues during the night compared to the day for bed bugs (Aak et al. 2014), suggesting there are likely chemosensory changes related to thermal- and CO2-sensing associated with daily rhythms. The completion of the genomes for multiple blood-feeding hemipterans (Mesquita et al. 2015; Benoit et al. 2016; Rosenfeld et al. 2016) could allow for more in-depth studies on mechanisms of sleep in these disease vectors (Mesquita et al. 2015; Benoit et al. 2016; Rosenfeld et al. 2016).

Ticks

There are two major groups of ticks, Argasidae (soft ticks) and Ixodidae (hard ticks), which have different lifestyles (Sonenshine and Roe 2013). In specific, hard ticks will feed for multiple days (only two to three feedings per lifecycle), while argasid ticks are adapted to feeding rapidly (an hour or less; which will feed multiple times). For general activity, some hard ticks (Ixodidae) are active during the scotophase (e.g., Ixodes ricinus [Babenko,1974]) and other species are active during the dawn/dusk or the photophase (e.g., Dermacentor variabilis); (Atwood and Sonenshine 1967). Soft ticks (Argasidae), as nest parasites, are most active during the night when their hosts are likely in the nest and asleep (Howell 1976), but this might be reversed if the host is nocturnal, similar to bat bugs. Daily rhythms in tick biology are directly influenced by environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and seasonality (Perret et al. 2000; Randolph 2004; Rosendale et al. 2016, 2019). Molecular factors that underlie circadian rhythms in ticks are yet to be examined, but identification of many of the orthologs core clock genes has been done through genomic analysis (Gulia-Nuss et al. 2016; Jia et al. 2020).

Ticks have the potential to have the most unique forms of sleep among blood-feeding arthropods, as extended periods of inactivity, defined as quiescence, occur commonly (Belozerov 1982, 2009; Yoder et al. 2016; Rosendale et al. 2019). During these extended periods, using behavioral correlates (active vs inactive periods) to assess factors such as sleep and daily rhythms will be difficult as ticks sometimes do not move (or have limited movement) for days or weeks. The big question remains for ticks: Is quiescence equivalent to sleep? This period does have the hallmark of sleep-like states with reduced sensitivity to host cues (Belozerov 2009), but is this a sleep period or is this more equivalent to diapause? Ticks do have periods of a diapause-like state that can be induced by cold and short day length (Belozerov 2009; Yoder et al. 2016). This suggests that quiescent periods are likely to be sleep-like states, but it is not clear if both processes are distinguishable. Importantly, these sleep-like quiescent states could be an important factor for tick survival as prolonged starvation resistance (months to years) could be a critical factor for ticks as “sit and wait” strategies (Lighton and Fielden 1995; Rosendale et al. 2019).

Other blood-feeding arthropods

Outside of the previously mentioned blood-feeding arthropod groups, sleep, or for that matter circadian, studies have been limited. For sand flies, activity reaches its peak during the light-to-dark transition (i.e., dusk), and activity is higher during the scotophase than the photophase (Morrison et al. 1993; Meireles-Filho et al. 2006; Minter and Brown 2010), suggesting that a sleep-like state is consolidated during the photophase. Circadian and sleep profile studies have been lacking in lice and other parasites that live on the hosts (bat flies and sheep ked), which might be difficult to assess as these species remain on-host for most or their entire life cycle. Importantly, clock- and sleep-associated genes have been identified in the louse and sheep ked genomes (Kirkness et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2023), suggesting the potential for rhythmic profiles. Assessing daily and activity patterns will be difficult as blood feeding occurs every few hours, which will require video tracking on a host or an artificial feeding membrane. Cat fleas have been noted to have increased activity during the night (Koehler et al. 1989; Kern et al. 1992), suggesting that there will be significantly decreased activity and mostly sleep during the day. Sleep and circadian behaviors of blood-feeding species that predominantly parasitize livestock have been understudied, even though some species, such as stable flies, can cause billions in damage (Olafson et al. 2021). Many blood-feeding arthropods have had their genomes sequenced (Kirkness et al. 2010; Gulia-Nuss et al. 2016; Driscoll et al. 2020; Thomas et al. 2020; Olafson et al. 2021; Labbé et al. 2023), which can allow for the identification of genes that underlie or are impacted by sleep in these understudied blood-feeding arthropods.

Various states of dormancy in blood-feeding arthropods: role of sleep

Periods of hibernation are critical to the survival of blood-feeding arthropods during periods of adverse conditions, especially dry seasons, or the winter months (Denlinger 2022). For blood-feeding arthropods, this may be critical as the host may also be in hibernation, thus blood sources may not be available. The specific stage at which dormancy occurs varies between species, for example, mosquitoes can undergo dormancy as eggs, larvae, and adults, while other blood-feeding flies likely undergo dormancy as pupae (Denlinger and Armbruster 2014; Denlinger 2022). Egg, larval, and pupal dormancy largely involves a suspension of development (Denlinger 2022). For adults, dormancy could involve changes in the sleep patterns of insects, but this has remained an understudied area for all invertebrate systems. Importantly, periods of dormancy are not just increased sleep, but could vary from no differences in sleep to a lack of sleep. Indeed, some animals must undergo periodic termination of dormancy to allow for periods of sleep (Daan et al. 1991; Trachsel et al. 1991). For blood-feeding arthropods that undergo dormancy as adults, studies will be required on specific species to assess how sleep may be impacted during dormancy.

Shifts in sleep profiles of blood-feeding arthropods by light pollution

Among various abiotic cues in nature, light is one of the most potent and dominant stimuli to entrain the circadian clocks in living organisms (Devlin and Kay 2001; Grippo and Güler 2019). Under light–dark cycles, circadian rhythms for Drosophila are much stronger in sleep (Guo et al. 2018), locomotor activity (Schlichting and Helfrich-Förster 2015), and olfaction (Tanoue et al. 2004). Since light is a central modulator of circadian systems, the light input into the central and peripheral clocks allows organisms to align or synchronize their physiology, behavior, and cognitive functions to environmental changes (LeGates et al. 2014; Coetzee et al. 2022). If animals experience light stimuli at irregular times or lengths, which misalign the organism’s temporal niche, this may lead to a direct or indirect harmful light effect on their fitness or survival (Jones et al. 2015; Bedrosian and Nelson 2017). Moreover, short-term photic stimulation may elicit acute effects due to the disruption of circadian rhythms (Gronfier et al. 2004; Rahman et al. 2017; Walker et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2023), while long-term exposure to light may further influence many aspects of circadian features like phase and period of the pacemaker because of the integration of the photic effect into circadian rhythms or desynchrony between clocks and lighting conditions (Fonken and Nelson 2014). Light pollution is rapidly increasing with growing urbanization as one of the key factors disturbing or even threatening most living organisms’ lives (Kyba et al. 2023). Since light is a well-known primary cue to entrain the circadian clock, any change in temporal, spatial, and spectral components of light conditions is likely to lead to biological effects on gene expression, physiological processes, and behaviors of individual animals (Owens and Lewis 2018; Bani Assadi and Fraser 2021; Kumar et al. 2021; Stewart 2021; Wilson et al. 2021). Artificial light at night (ALAN) has become a global change driver (Davies and Smyth 2018) and widely impacts ecosystem and human health in many aspects, including not only individuals but also intra- and inter-specific interactions (Chown and Gaston 2008; van Geffen et al. 2015; Knop et al. 2017; Kernbach et al. 2018; Giavi et al. 2020; Vaz et al. 2021; Velasque et al. 2023). In fruit flies, exposure to light at night disrupts important biology, including metabolism, reproduction, sleep, eclosion rhythm, and survival (Thakurdas et al. 2009; McLay et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2022).

Acute, temporal effect of ALAN on mosquito behaviors: an example of how daytime- vs. nighttime-active species could be impacted by ALAN

Mosquito activities peak at daytime (diurnal), nighttime (nocturnal), and twilight (crepuscular) depending on the species. Their activity pattern likely corresponds to mosquito–host interaction, biting frequencies, and disease transmission (Ajayi et al. 2022). In Drosophila and other insects, light exposure during the night causes phase advance or delay in their activity rhythms due to the light-modulated photosensitive cryptochrome (CRY) conformational change and Timeless (TIM) degradation (Thakurdas et al. 2009; Tang and Juusola 2010; Lin et al. 2023). Most importantly, it is known that the time and length of light exposure shape activity patterns differentially through CRY–TIM interaction (Suri et al. 1998; Kistenpfennig et al. 2012; Vinayak et al. 2013), and this phenomenon can be depicted by a phase–response curve, which reveals the light effect (i.e., phase advance or delay) at specific times (Vinayak et al. 2013). Light also affects the transcript oscillation of clock genes and other genes involved in a variety of physiological processes like cellular communication, immunity, metabolism, and detoxification (Wijnen et al. 2006; Das and Dimopoulos 2008; Adewoye et al. 2015). Without any doubt, CRY plays an important role in the temporal integration of light input into the clockworks as CRY mutants are less photosensitive and show less magnitude of phase advances and delays compared to control flies (Kistenpfennig et al. 2012). Moreover, clock mutants in response to light at night are still able to shift their activities (Kempinger et al. 2009); thus, this light-mediated process involves clock-dependent and clock-independent pathways (Das and Dimopoulos 2008; Kempinger et al. 2009).

Behavioral changes

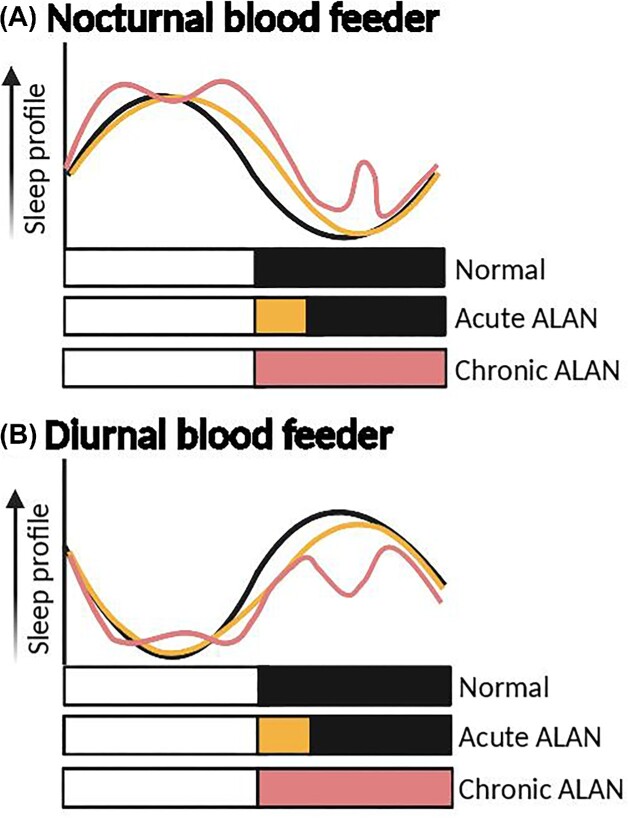

Although there is little direct evidence of ALAN’s impact on blood-feeding arthropods’ sleep, studies have shown that just like in mammals and Drosophila, light also modulates the activities of blood-feeding arthropods during the night (Fig. 2, Coetzee et al. 2022). The effect of light-mediated behaviors is time-of-day specific and involves masking effects and circadian regulation. When nighttime-active mosquitoes, An. gambiae, are exposed to the light pulse at the onset of the night (ZT12), their flight activities significantly reduce (Sheppard et al. 2017; see Fig. 2A). Conversely, light pulses in the rest of the night (ZT16, ZT22, and ZT24) lead to increasing activities. Interestingly, although light pulses induce increasing flight activity, photic stimulation inhibits the biting activity at almost all phases of the night (ZT12, ZT14, ZT16, ZT18, and ZT20) and feeding propensity (Das and Dimopoulos 2008; Sheppard et al. 2017). Depending on the length of the light stimulation, the photomodulation of An. gambiae feeding behaviors could be transient without phase shift (5 min light pulses) or immediate with 3–4 h phase advance (2 h light pulses); (Das and Dimopoulos 2008). Moreover, the shorter the duration between light pulse and blood provision, the larger the degree of inhibition of feeding behavior (Das and Dimopoulos 2008). Similarly, ALAN-exposed nighttime active Cx. pipiens are less active in the evening and lay fewer eggs (lower fecundity; Honnen et al. 2019). In the daytime-active mosquitoes Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, ALAN exposure increases nocturnal host-seeking and biting behavior is elevated (Kawada et al. 2005; Rund et al. 2020), and there is a positive correlation between host-seeking behavior and light intensity (Kawada et al. 2005; Rund et al. 2020; see Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Potential influence of light pollution on the sleep of blood-feeding arthropods. Predicted sleep profiles of a typical (A) nocturnal and (B) diurnal blood feeder under different light exposures during a circadian day. Sleep profiles are based on general trends of increased sleep in the light cycle for nocturnal insects and reduced sleep in the light cycle for diurnal insects. Black, orange, and red solid lines show the normalized profiles under normal light–dark conditions, acute ALAN, and chronic ALAN, respectively. Extension of the day by the ALAN is expected to prolong or reduce the sleep period in the scotophase or photophase period. Chronic ALAN will likely yield more unpredictable and sporadic periods of sleep across the day. Other parameters, such as random periods of light during the night, are not shown but will likely impact the sleep profiles. White, dark, orange, and red horizontal bars represent photophase, scotophase, acute ALAN, and chronic ALAN, respectively. Created with BioRender.com, check online for colored version.

Gene expression changes underlying ALAN

At the transcriptomic level, various genes related to the circadian clock, metabolism, immunity, and chemosensory are known to be differentially regulated in response to the light stimulus at night (Das and Dimopoulos 2008; Honnen et al. 2019). Among these genes, RNAi silencing in light-pulse-regulated circadian and chemosensory genes in An. gambiae leads to the increase and decrease of nighttime feeding behaviors, respectively (Das and Dimopoulos 2008), suggesting a molecular link between light pulses and these genes. Light-pulse induced transcriptomic change is also observed in Cx. pipiens (Honnen et al. 2016, 2019). This differential gene expression is in a sex-specific manner since ALAN has a stronger effect on the expression in males than that in females (Honnen et al. 2016). More extensive studies are necessary to assess how ALAN impacts molecular mechanisms of circadian rhythms.

Effects of chronic ALAN exposure

ALAN causes alterations in various aspects of the physiological processes and behaviors, but very few studies focus on the effect of chronic exposure (multiple days to weeks) in mosquitoes. Under short day length and low temperature, photoperiodically induced diapauses take place in some mosquito species and help them survive the winter (Sanburg and Larsen 1973; Armbruster 2016). ALAN will cause photoperiod extension and impact diapause incidence in different insect species (Van Geffen et al. 2014; Westby and Medley 2020; Fyie et al. 2021). In Ae. albopictus, the proportion of eggs in diapause is significantly reduced by chronic exposure to ALAN (Westby and Medley 2020). Similarly, female Cx. pipiens exposed to ALAN throughout their lifespan will avert diapause and show abnormal seasonal phenotypes in lipid content, egg follicle size, and blood-feeding behaviors (Fyie et al. 2021).

Impact of pathogens and microbial partners on the sleep cycles of blood-feeding arthropods

Blood-feeding arthropods are exposed to a myriad of transmissible infectious agents ranging from viruses and bacteria to protozoan parasites (Hill et al. 2005; Krenn and Aspöck 2012; Mathison and Pritt 2014). In other instances, insects and other arthropods can be exposed to pathogens such as entomopathogenic fungi that act predominantly to cause diseases in the vector hosts (Hajek and St. Leger 1994). Lastly, the presence of specific microbial partners, for example, gut microbes or more intimate bacterial residents such as Wolbachia could have an impact on the sleep of arthropods (Albertson et al. 2013; Vale and Jardine 2015; Bi et al. 2018; Morioka et al. 2018; Silva et al. 2021). Although sleep was not quantified in this study, Ae. aegypti mosquitoes showed an increase in daytime activity when infected with Wolbachia, suggesting a potential influence on sleep duration during the entire day (Evans et al. 2009). In general, the role of sleep-immune response–infection dynamics has been the focus of many studies, especially in fruit flies (Cirelli et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2007), where increased sleep was documented to be associated with infection (Kuo et al. 2010; Kuo and Williams 2014; Toda et al. 2019). As such, sleep is proposed to be an adaptive response to infection and in promoting survival. The direct impact of infection is likely to increase sleep to allow for immune response and recovery, which is consistent with the response noted in Drosophila (Toda et al. 2019). In contrast to the effect of Wolbachia in the previous Ae. aegypti study, studies in An. stephensi reported a reduction in flight performance after Plasmodium infections (Schiefer et al. 1977; Rowland and Boersma 1988). However, it is unclear if this reduced flight performance translates to increased sleep. Similar to the influence of infection on sleep dynamics, sleep deprivation could directly impact the susceptibility of blood-feeding insects to infection, thereby establishing a bi-directional relationship between sleep and the acquisition of transmittable pathogens.

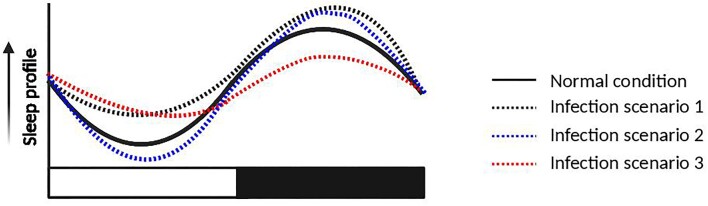

Altogether, based on previous locomotor activity studies in mosquitoes (Schiefer et al. 1977; Rowland and Boersma 1988; Evans et al. 2009) and direct evaluation in fruit flies, we predict that sleep dynamics would also be modulated in varied ways under different infection scenarios in blood-feeding arthropods (Fig. 3). In Drosophila, increased sleep duration, altered sleep time, and sometimes increased nocturnal activities (due to sleep disturbance) have been reported in specific studies evaluating the influence of Wolbachia (Albertson et al. 2013; Bi et al. 2018; Morioka et al. 2018), and both bacterial and viral infections resulted in increased sleep in this insect system (Kuo et al. 2010; Kuo and Williams 2014; Vale and Jardine 2015; Toda et al. 2019). We predict similar results in blood-feeding arthropods; however, future studies in multiple disease vectors will be necessary to confirm the effect of infection status on sleep dynamics.

Fig. 3.

Impact of microbial infection on the sleep cycle of blood-feeding arthropods. Predicted sleep profiles of a typical diurnal blood feeder under different conditions of infection. Sleep and activity patterns could be shifted to increase interaction with potential hosts to improve transmission or promote the survival of the vector. Predictions are based on previous studies in mosquitoes and fruit flies reported in the main text. Other potential shifts, such as a general reduction or increase in sleep overall, depend on the specific interaction between host and microbe. Furthermore, other factors that could be altered due to infection, such as increased metabolism, could impact sleep patterns in unexpected ways. White and dark horizontal bars represent photophase and scotophase, respectively. Created with BioRender.com, check online for colored version.

Influence of sleep in blood-feeding arthropods on interactions with their host and disease transmission

Disease transmission by blood-feeding arthropods is driven by the rate of contact between hosts and vectors, as the causative agents of vector-borne diseases are either injected in the host bloodstream during biting or deposited on the host skin when the vector defecates (Becker 2008; Klotz et al. 2014). Of interest, host and vector rhythms are critical to the initial infection by disease-causing pathogens and subsequent transmission to the next host (Hawking 1970; Rund et al. 2016; Reece et al. 2017). When an uninfected vector bites an infected host, the timing of the mobilization of the pathogen in the blood will also matter, and, for example, parasites have synchronized to the vectors’ rhythms by migrating to the peripheral blood vessels when vectors are actively host-seeking, increasing their chances of being transmitted (Hawking 1970, 1975; Aschoff 1989; Lazzari and Insausti 2008). Surprisingly, targeted studies similar to the aforementioned that investigated the rhythmicity of parasites in response to the vectors’ rhythms are limited, except for a few other projects on mosquito–malaria dynamics (Rund et al. 2016; Reece et al. 2017; Schneider et al. 2018). Most research has only focused on the diel rhythms of parasites within vertebrate hosts or in vitro studies on stages that are infective to vertebrates (Hawking 1975; Reece et al. 2017; Rijo-Ferreira et al. 2017, 2018; Prior et al. 2020). Biological rhythms, including sleep–wake patterns, are therefore important aspects of the vector–host relationship as well as the vector–pathogen relationship (Reece et al. 2017; Prior et al. 2020).

Importantly, sleep could affect the ability of the vector to detect and respond to host-emitted cues. A hallmark of sleep is an increased sensory threshold (or a reduced response to sensory cues). In non-blood-feeding insects such as honeybees, rhythms in sensory thresholds align with sleep patterns and ventilatory activity (Sauer et al. 2003). In fruit flies, reduced sensory responsiveness was also observed during sleep (Hendricks et al. 2000). Combined with daily rhythms in overall sensory sensitivity (Rund et al. 2013a; Eilerts et al. 2018) and sensory gene expression (Rund et al. 2013b), a higher sensory threshold could serve an additional adaptive function by ensuring that vectors not only avoid responding to host cues when not in the optimal physiological and temporal context (i.e., in the proper nutritional or reproductive state, depending on the species, and when the host is available but the least active) but also do not respond when not rested. Considering the widespread effects of sleep deprivation on honeybees’ memory (Hussaini et al. 2009), the precision of their waggle dance signaling (Klein et al. 2010), and their ability to return successfully to their hive (Beyaert et al. 2012), or its negative effects on fruit flies’ short- and long-term memory (Seugnet et al. 2009, 2011), it is expected that the lack of sleep will also negatively impact the ability of vectors to successfully identify, locate, and navigate to their hosts. Since a prolonged period of inactivity correlates with reduced neuronal activity in the brain of flies (Nitz et al. 2002), future studies in disease vectors will be needed to evaluate the neural correlates of sleep. However, while there are standardized methods for peripheral electrophysiological recordings in several vectors (Peach et al. 2019; Lahondère 2022), neurophysiological studies in the central brain of vectors have been so far limited to mosquitoes (Vinauger et al. 2018). Optophysiological methods (e.g., calcium imaging, two-photon microscopy) bear the potential to reveal trends in patterns of neural activity across the brain of vectors, but currently lack the temporal resolution to finely dissect the impact of sleep on individual neuron activity (Lahondère et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2022; Wolff et al. 2023).

Another important time-dependent aspect of vector–host interaction is that the time of day will affect the behavioral state of the host and, by extension, its level of defensiveness. In mosquitoes, the diurnal Ae. aegypti and nocturnal An. coluzii differed in the strategy they employ to avoid potential host defensive maneuvers such as a fictive swat (Cribellier et al. 2022), where Ae. aegypti appears to rely on vision more than its counterpart, both in flight (Cribellier et al. 2022) and when landing on a host mimic (Wynne et al. 2022). In addition, the association between sensory cues signaling the level of defensiveness of an individual host can be learned by female mosquitoes, who will then bias their host preference based on these past experiences with the host (Vinauger et al. 2018). With important consequences for sensory processing, learning-induced plasticity, and decision-making processes across insects (Hussaini et al. 2009; Seugnet et al. 2011; Buchert et al. 2022), the sleep status or deprivation of sleep can likely alter their ability to survive their hosts’ defensive strategies. This could occur either via reduced sensory detection and processing of threats or by increased risk-taking by the vector. Predation risk could also be increased, where the inability of sleep-deprived mosquitoes or other blood-feeding vectors to avoid predators could lead to higher mortality rates. In this context, a control strategy relying on disrupting the natural sleep–wake cycles of vectors would appear advantageous as it would reduce their ability to locate, bite, and survive interactions with their hosts.

Conclusions

Understanding sleep in blood-feeding arthropods will be critical to understanding their biology and assessing pathogen transmission. Sleep is likely to have a significant impact on a multitude of factors ranging from the initial immune response to when individuals will interact with the host and feed. Thus, shifted sleep patterns or sleep deprivation will directly impact aspects relating to vectorial capacity. However, this lack of extensive sleep studies in blood-feeding arthropods might be due to limited circadian studies in these systems when compared to Drosophila systems (Benoit and Vinauger 2022). Furthermore, sleep-based studies need to be conducted in spaces without exposure to hosts or other disturbances, so isolated areas outside of normal lab space are necessary to prevent exposure to cues that can modulate sleep. The major aspects that need to be examined include the evaluation of the influence of sleep on immune function following blood feeding and the impact of periods of sleep deprivation on the susceptibility of vectors to pathogens that can be transmitted to a host. Studies beyond mosquitoes need to be conducted as sleep investigation, or even extensive circadian studies, in other blood-feeding genera is lacking. Even in nonhematophagous insects, sleep studies across more arthropod taxa are necessary since there is a paucity of knowledge outside of fruit flies and honeybees.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Oluwaseun M Ajayi, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USA.

Nicole E Wynne, Department of Biochemistry, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA.

Shyh-Chi Chen, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USA.

Clément Vinauger, Department of Biochemistry, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA.

Joshua B Benoit, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI148551 (to J.B.B.), University of Cincinnati Sigma Xi (to O.M.A.), and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture of the United States Department of Agriculture, Hatch project 1017860 (to C.V.), and partially supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award number R01AI155785 (to C.V.). Direct support for the sleep-based studies was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AI166633 (to J.B.B. and C.V.).

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.

References

- Aak A, Rukke BA, Soleng A, Rosnes MK. 2014. Questing activity in bed bug populations: male and female responses to host signals. Physiol Entomol. 39:199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkarim EI, Brady J. 1984. Changing visual responsiveness in pregnant and larvipositing tsetse flies, Glossina morsitans. Physiol Entomol. 9:125–31. [Google Scholar]

- Adewoye AB, Kyriacou CP, Tauber E. 2015. Identification and functional analysis of early gene expression induced by circadian light-resetting in Drosophila. BMC Genomics. 16:570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi OM, Eilerts DF, Bailey ST, Vinauger C, Benoit JB. 2020. Do mosquitoes sleep?. Trends Parasitol. 36:888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi OM, Marlman JM, Gleitz LA, Smith ES, Piller BD, Krupa JA, Vinauger C, Benoit JB. 2022. Behavioral and postural analyses establish sleep-like states for mosquitoes that can impact host landing and blood feeding. J Exp Biol. 225:jeb244032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson R, Tan V, Leads RR, Reyes M, Sullivan W, Casper-Lindley C. 2013. Mapping Wolbachia distributions in the adult Drosophila brain. Cell Microbiol. 15:1527–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allada R, Cirelli C, Sehgal A. 2017. Molecular mechanisms of sleep homeostasis in flies and mammals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 9:a027730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allada R, Siegel JM. 2008. Unearthing the phylogenetic roots of sleep. Curr Biol. 18:R670–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvar J, Alves F, Bucheton B, Burrows L, Büscher P, Carrillo E, Felger I, Hübner MP, Moreno J, Pinazo M-Jet al. 2020. Implications of asymptomatic infection for the natural history of selected parasitic tropical diseases. Semin Immunopathol. 42:231–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampleford EJ, Davey KG. 1989. Egg laying in the insect Rhodnius prolixus is timed in a circadian fashion. J Insect Physiol. 35:183–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ampleford EJ, Steel CGH. 1982. Circadian control of ecdysis in Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera). J Comp Physiol. 147:281–6. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen FS. 1968. Sleep in moths and its dependence on the frequency of stimulation in Anagasta kuehniella. Opusc Ent. 33:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Andretic R, Shaw PJ. 2005. Essentials of sleep recordings in Drosophila: moving beyond sleep time. Methods Enzymol. 393:759–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster PA. 2016. Photoperiodic diapause and the establishment of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: culicidae) in North America. J Med Entomol. 53:1013–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschoff J. 1989. Temporal orientation: circadian clocks in animals and humans. Anim Behav. 37:881–96. [Google Scholar]

- Attardo GM, Abd-Alla AMM, Acosta-Serrano A, Allen JE, Bateta R, Benoit JB, Bourtzis K, Caers J, Caljon G, Christensen MBet al. 2019. Comparative genomic analysis of six Glossina genomes, vectors of African trypanosomes. Genome Biol. 20:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood EL, Sonenshine DE. 1967. Activity of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Acarina: ixodidae), in relation to solar energy changes. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 60:354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko LV. 1974. Daily fluctuations in the activity of starving nymphs of Ixodes ricinus L. and Ixodes persulcatus P. Sch. (Parasitiformes: ixodiadae). Med Parazitol. 43:520–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani Assadi S, Fraser KC. 2021. The influence of different light wavelengths of anthropogenic light at night on nestling development and the timing of post-fledge movements in a migratory songbird. Front Ecol Evol. 9:741. [Google Scholar]

- Barrozo RB, Schilman PE, Minoli SA, Lazzari CR. 2004. Daily rhythms in disease-vector insects. Biol Rhythm Res. 35:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver LM, Gvakharia BO, Vollintine TS, Hege DM, Stanewsky R, Giebultowicz JM. 2002. Loss of circadian clock function decreases reproductive fitness in males of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99:2134–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebas P, Cymborowski B, Giebultowicz JM. 2001. Circadian rhythm of sperm release in males of the cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Insect Physiol. 47:859–66. [Google Scholar]

- Becker N. 2008. Influence of climate change on mosquito development and mosquito-borne diseases in Europe. Parasitol Res. 103:S19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedrosian TA, Nelson RJ. 2017. Timing of light exposure affects mood and brain circuits. Transl Psychiatry. 7:e1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belozerov VN. 1982. Diapause and biological rhythms in ticks. Physiol Ticks. 469–500.. Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Belozerov VN. 2009. Diapause and quiescence as two main kinds of dormancy and their significance in life cycles of mites and ticks (Chelicerata: Arachnida: Acari). Acarina. 17:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JB, Adelman ZN, Reinhardt K, Dolan A, Poelchau M, Jennings EC, Szuter EM, Hagan RW, Gujar H, Shukla JNet al. 2016. Unique features of a global human ectoparasite identified through sequencing of the bed bug genome. Nat Commun. 7:10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JB, Attardo GM, Baumann AA, Michalkova V, Aksoy S. 2015. Adenotrophic viviparity in tsetse flies: potential for population control and as an insect model for lactation. Annu Rev Entomol. 60:351–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JB, Denlinger DL. 2010. Meeting the challenges of on-host and off-host water balance in blood-feeding arthropods. J Insect Physiol. 56:1366–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JB, McCluney KE, DeGennaro MJ, Dow JAT. 2023. Dehydration dynamics in terrestrial arthropods: from water sensing to trophic interactions. Annu Rev Entomol. 68:129–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JB, Vinauger C. 2022. Chronobiology of blood-feeding arthropods: influences on their role as disease vectors. In: Hill S, Ignell R, Lorenzo M, editors. Sensory ecology of disease vectors. Wageningen, The Netherlands, Wageningen Academic Publishers. p.815–49. [Google Scholar]

- Beyaert L, Greggers U, Menzel R. 2012. Honeybees consolidate navigation memory during sleep. J Exp Biol. 215:3981–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi J, Sehgal A, Williams JA, Wang YF. 2018. Wolbachia affects sleep behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol. 107:81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch G. 2010. The social clock of the honeybee. J Biol Rhythms. 25:307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady J. 1972. The visual responsiveness of the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans Westw. (Glossinidae) to moving objects: the effects of hunger, sex, host odour and stimulus characteristics. Bull Entomol Res. 62:257–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brady J. 1973. Changes in the probing responsiveness of starving tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans Westw.) (Diptera, Glossinidae). Bull Entomol Res. 63:247–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brady J. 1988. The circadian organization of behavior: timekeeping in the tsetse fly, a model system. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 18: 153–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brady J, Crump AJ. 1978. The control of circadian activity rhythms in tsetse flies: environment or physiological clock?. Physiol Entomol. 3:177–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brady J, Gibson G. 1983. Activity patterns in pregnant tsetse flies, Glossina morsitans. Physiol Entomol. 8:359–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brody S. 2020. A comparison of the Neurospora and Drosophila clocks. J Biol Rhythms. 35:119–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchert SN, Murakami P, Kalavadia AH, Reyes MT, Sitaraman D. 2022. Sleep correlates with behavioral decision making critical for reproductive output in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 264:111114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushey D, Tononi G, Cirelli C. 2015. Sleep- and wake-dependent changes in neuronal activity and reactivity demonstrated in fly neurons using in vivo calcium imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:4785–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busvine JR. 1993. Disease Transmission by Insects Springer. Berlin: xii, 361, illus., DM 98.00 (3-540-55457-2). [Google Scholar]

- Chown SL, Gaston KJ. 2008. Macrophysiology for a changing world. Proc Biol Sci. 275:1469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C. 2009. The genetic and molecular regulation of sleep: from fruit flies to humans. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10:549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C, LaVaute TM, Tononi G. 2005. Sleep and wakefulness modulate gene expression in Drosophila. J Neurochem. 94:1411–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN. 1999. The biology of mosquitoes. Volume 2: sensory reception and behaviour CABI publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee BWT, Gaston KJ, Koekemoer LL, Kruger T, Riddin MA, Smit IPJ. 2022. Artificial light as a modulator of mosquito-borne disease risk. Front Ecol Evol. 9:768090. [Google Scholar]

- Cribellier A, Straw AD, Spitzen J, Pieters RPM, van Leeuwen JL, Muijres FT. 2022. Diurnal and nocturnal mosquitoes escape looming threats using distinct flight strategies. Curr Biol. 32:1232–1246.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump AJ, Brady J. 1979. Circadian activity patterns in three species of tsetse fly: Glossina palpalis, austeni and morsitans. Physiol Entomol. 4:311–8. [Google Scholar]

- Daan S, Barnes BM, Strijkstra AM. 1991. Warming up for sleep?—ground squirrels sleep during arousals from hibernation. Neurosci Lett. 128:265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Dimopoulos G. 2008. Molecular analysis of photic inhibition of blood-feeding in Anopheles gambiae. BMC Physiol. 8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies TW, Smyth T. 2018. Why artificial light at night should be a focus for global change research in the 21st century. Glob Change Biol. 24:872–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean GJW, Clements SA, Paget J. 1969. Observations on sex attraction and mating behaviour of the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans orientalis Vanderplank. Bull Entomol Res. 59:355–65. [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger DL. 2022. Insect Diapause. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger DL, Armbruster PA. 2014. Mosquito diapause. Annu Rev Entomol. 59:73–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin PF, Kay SA. 2001. Circadian photoperception. Annu Rev Physiol. 63:677–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll TP, Verhoeve VI, Gillespie JJ, Johnston JS, Guillotte ML, Rennoll-Bankert KE, Rahman MS, Hagen D, Elsik CG, Macaluso KRet al. 2020. A chromosome-level assembly of the cat flea genome uncovers rampant gene duplication and genome size plasticity. BMC Biol. 18:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowy C, Sehgal A. 2017. Circadian rhythms and sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 205:1373–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall LB. 2019. Mosquito host-seeking regulation: targets for behavioral control. Trends Parasitol. 35:704–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilerts DF, VanderGiessen M, Bose EA, Broxton K, Insects2018. Odor-specific daily rhythms in the olfactory sensitivity and behavior of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Insects. 9:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson G, Magzamen S, Carter E, Sharp JL, Reynolds SJ, Schaeffer JW. 2019. Characterization of indoor air quality on a college campus: a pilot study. IJERPH. 16:2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans O, Caragata EP, McMeniman CJ, Woolfit M, Green DC, Williams CR, Franklin CE, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. 2009. Increased locomotor activity and metabolism of Aedes aegypti infected with a life-shortening strain of Wolbachia pipientis. J Exp Biol. 212:1436–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonken LK, Nelson RJ. 2014. The effects of light at night on circadian clocks and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 35:648–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyie LR, Gardiner MM, Meuti ME. 2021. Artificial light at night alters the seasonal responses of biting mosquitoes. J Insect Physiol. 129:104194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile C, Rivas GB da S, Lima JBP, Bruno RV, Peixoto AA. 2013. Circadian clock of Aedes aegypti: effects of blood-feeding, insemination and RNA interference. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 108:80–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavi S, Blösch S, Schuster G, Knop E. 2020. Artificial light at night can modify ecosystem functioning beyond the lit area. Sci Rep. 10:11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Torr SJ. 1999. Visual and olfactory responses of haematophagous Diptera to host stimuli. Medical Vet Entomolo. 13:2–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo RM, Güler AD. 2019. Focus: clocks and cycles: dopamine signaling in circadian photoentrainment: consequences of desynchrony. Yale J Biol Med. 92:271–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronfier C, Wright KP, Kronauer RE, Jewett ME, Czeisler, CA. 2004. Efficacy of a single sequence of intermittent bright light pulses for delaying circadian phase in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 287:E174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerenstein PG, Lazzari CR. 2009. Host-seeking: how triatomines acquire and make use of information to find blood. Acta Trop. 110:148–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulia-Nuss M, Nuss AB, Meyer JM, Sonenshine DE, Roe RM, Waterhouse RM, Sattelle DB, de la Fuente J, Ribeiro JM, Megy Ket al. 2016. Genomic insights into the Ixodes scapularis tick vector of Lyme disease. Nat Commun. 7:10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Holla M, Díaz MM, Rosbash M. 2018. A circadian output circuit controls sleep-wake arousal in Drosophila. Neuron. 100:624–635.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan RW, Didion EM, Rosselot AE, Holmes CJ, Siler SC, Rosendale AJ, Hendershot JM, Elliot KSB, Jennings EC, Nine GAet al. 2018. Dehydration prompts increased activity and blood feeding by mosquitoes. Sci Rep. 8:6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek AE, Leger RJ St.. 1994. Interactions between fungal pathogens and insect hosts. Annu Rev Entomol. 39:293–322. [Google Scholar]

- Harbison ST, McCoy LJ, Mackay TFC. 2013. Genome-wide association study of sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Genomics. 14:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufe WO. 1963. Ethological and statistical aspects of a quantal response in mosquitoes to environmental stimuli. Behaviour. 20:221–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking F. 1970. The clock of the malaria parasite. Sci Am. 222:123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawking F. 1975. Circadian and other rhythms of parasites. Adv Parasitol. 13:123–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Förster C. 2018. Sleep in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 63:69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JC, Finn SM, Panckeri KA, Chavkin J, Williams JA, Sehgal A, Pack AI. 2000. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron. 25:129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JC, Lu S, Kume K, Yin JCP, Yang Z, Sehgal A. 2003. Gender dimorphism in the role of cycle (BMAL1) in rest, rest regulation, and longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Rhythms. 18:12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CA, Kafatos FC, Stansfield SK, Collins FH. 2005. Arthropod-borne diseases: vector control in the genomics era. Nat Rev Microbiol. 3:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honnen AC, Johnston PR, Monaghan MT. 2016. Sex-specific gene expression in the mosquito Culex pipiens f. molestus in response to artificial light at night. BMC Genomics. 17:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honnen A-C, Kypke JL, Hölker F. 2019. Artificial light at night influences clock-gene expression, activity, and fecundity in the mosquito Culex pipiens f. molestus. Sustainability. 11:6220. [Google Scholar]

- Howell FG. 1976. Influence of the daily light cycle on the behavior of Argas cooleyi (Acarina: argasidae). J Med Entomol. 13:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Leming MT, Metoxen AJ, Whaley MA, O'Tousa JE. 2012. Light-mediated control of rhodopsin movement in mosquito photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 32:13661–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussaini SA, Bogusch L, Landgraf T, Menzel R. 2009. Sleep deprivation affects extinction but not acquisition memory in honeybees. Learn Mem. 16:698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Glossina Genome Initiative . 2014. Genome sequence of the tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans): vector of African trypanosomiasis. Science. 344:380–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito F, Awasaki T. 2022. Comparative analysis of temperature preference behavior and effects of temperature on daily behavior in 11 Drosophila species. Sci Rep. 12:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia N, Wang J, Shi W, Du L, Sun Y, Zhan W, Jiang JF, Wang Q, Zhang B, Ji Pet al. 2020. Large-scale comparative analyses of tick genomes elucidate their genetic diversity and vector capacities. Cell. 182:1328–1340.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TM, Durrant J, Michaelides EB, Green MP. 2015. Melatonin: a possible link between the presence of artificial light at night and reductions in biological fitness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 370:20140122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C-C, Wu P-C, Tseng C-H, Su H-J. 2015. Indoor air quality varies with ventilation types and working areas in hospitals. Build Environ. 85:190–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser W. 1988. Busy bees need rest, too. J Comp Physiol. 163:565–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser W. 1995. Rest at night in some solitary bees—a comparison with the sleep-like state of honey bees. Apidologie. 26:213–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser W, Steiner-Kaiser J. 1983. Neuronal correlates of sleep, wakefulness and arousal in a diurnal insect. Nature. 301:707–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada H, Takemura SY, Arikawa K, Takagi M. 2005. Comparative study on nocturnal behavior of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. J Med Entomol. 42:312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene AC, Duboue ER. 2018. The origins and evolution of sleep. J Exp Biol. 221:jeb159533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemenesi G, Bányai K. 2019. Tick-borne flaviviruses, with a focus on Powassan virus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 32:10–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempinger L, Dittmann R, Rieger D, Helfrich-Forster C. 2009. The nocturnal activity of fruit flies exposed to artificial moonlight is partly caused by direct light effects on the activity level that bypass the endogenous clock. Chronobiol Int. 26:151–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern WH Jr, Koehler PG, Patterson RS. 1992. Diel patterns of cat flea (Siphonaptera: pulicidae) egg and fecal deposition. J Med Entomol. 29:203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernbach ME, Hall RJ, Burkett-Cadena ND, Unnasch TR, Martin LB. 2018. Dim light at night: physiological effects and ecological consequences for infectious disease. Integr Comp Biol. 58:995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Son GI, Cho YH, Kim GH, Yoon SE, Kim YJ, Chung J, Lee E, Park JJ. 2022. Reduced branched-chain aminotransferase activity alleviates metabolic vulnerability caused by dim light exposure at night in Drosophila. J Neurogenet. 37:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Kaur M, Jang H-I, Kim Y-I. 2020. The circadian clock—a molecular tool for survival in cyanobacteria. Life. 10:365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness EF, Haas BJ, Sun W, Braig HR, Perotti MA, Clark JM, Lee SH, Robertson HM, Kennedy RC, Elhaik Eet al. 2010. Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:12168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistenpfennig C, Hirsh J, Yoshii T, Helfrich-Förster C. 2012. Phase-shifting the fruit fly clock without cryptochrome. J Biol Rhythms. 27:117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BA, Klein A, Wray MK, Mueller UG, Seeley TD. 2010. Sleep deprivation impairs precision of waggle dance signaling in honey bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:22705–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz SA, Dorn PL, Mosbacher M, Schmidt JO. 2014. Kissing bugs in the United States: risk for vector-borne disease in humans. Environ Health Insights. 8:49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klowden MJ. 1986. Effects of sugar deprivation on the host-seeking behaviour of gravid Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J Insect Physiol. 32:479–83. [Google Scholar]

- Knop E, Zoller L, Ryser R, Gerpe C, Hörler M, Fontaine C. 2017. Artificial light at night as a new threat to pollination. Nature. 548:206–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler PG, Leppla NC, Patterson RS. 1989. Circadian rhythm of cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) locomotion unaffected by ultrasound. J Econ Entomol. 82:516–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenn HW, Aspöck H. 2012. Form, function and evolution of the mouthparts of blood-feeding Arthropoda. Arthropod Structure Development. 41:101–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Malik S, Bhardwaj SK, Rani S. 2021. Impact of light at night is phase dependent: a study on migratory redheaded bunting (Emberiza bruniceps). Front Ecol Evol. 9:751072. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo TH, Pike DH, Beizaeipour Z, Williams JA. 2010. Sleep triggered by an immune response in Drosophila is regulated by the circadian clock and requires the NFκB Relish. BMC Neurosci. 11:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo TH, Williams JA. 2014. Increased sleep promotes survival during a bacterial infection in Drosophila. Sleep. 37:1077–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyba CCM, Altıntaş YÖ, Walker CE, Newhouse M. 2023. Citizen scientists report global rapid reductions in the visibility of stars from 2011 to 2022. Science. 379:265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbé F, Abdeladhim M, Abrudan J, Araki AS, Araujo RN, Arensburger P, Benoit JB, Brazil RP, Bruno RV, Bueno da Silva Rivas Get al. 2023. Genomic analysis of two phlebotomine sand fly vectors of Leishmania from the new and old World. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 17:e0010862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahondère C. 2022. Mosquito electroantennogram recordings. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2022:PROT107871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahondère C, Vinauger C, Okubo RP, Wolff GH, Chan JK, Akbari OS, Riffell JA. 2020. The olfactory basis of orchid pollination by mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:708–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]