Abstract

Microtubules play a central role in cytoskeletal changes during neuronal development and maintenance. Microtubule dynamics is essential to polarity and shape transitions underlying neural cell division, differentiation, motility, and maturation. Kinesin superfamily protein 2A is a member of human kinesin 13 gene family of proteins that depolymerize and destabilize microtubules. In dividing cells, kinesin superfamily protein 2A is involved in mitotic progression, spindle assembly, and chromosome segregation. In postmitotic neurons, it is required for axon/dendrite specification and extension, neuronal migration, connectivity, and survival. Humans with kinesin superfamily protein 2A mutations suffer from a variety of malformations of cortical development, epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and neurodegeneration. In this review, we discuss how kinesin superfamily protein 2A regulates neuronal development and function, and how its deregulation causes neurodevelopmental and neurological disorders.

Keywords: brain disorders, cortical malformations, kinesin, microtubules, neurodegeneration, neurodevelopment

Introduction

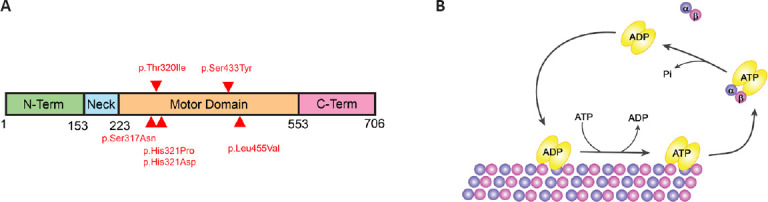

Microtubules (MTs) are essential components of the cytoskeleton implicated in different cellular functions. MTs are composed of heterodimers of α- and β-tubulin forming protofilaments. Tubulin subunits can be added or removed to grow or disassemble MTs in a process named dynamic instability. This process is essential to MT functions and is regulated by posttranslational modifications (PTM) of tubulin and the activity of different MT-associated proteins. In dividing cells for instance, microtubule poleward flux (that is when tubulin is added at the spindle poles and removed from the minus ends at the centrosome) is essential for mitotic progression, spindle assembly, and chromosome segregation. In mammals, the kinesin-13 family comprised 4 members: KIF2A, KIF2B, KIF2C (MCAK), and KIF24 (Ems-McClung and Walczak, 2010). These proteins bind MTs facilitating their depolymerization in ATP dependent manner (Desai et al., 1999). The motor domain (catalytic core) of KIF2A, KIF2B, and KIF2C is located in the middle of the molecule, meanwhile, KIF24 has it on the N-terminal (Miki et al., 2005). KIF2C is localized at the spindle poles, centromeres, and kinetochores, KIF2B at the kinetochores and spindle poles, and KIF2A at the spindle poles and centrosomes (Ems-McClung and Walczak, 2010). Kinesin-13 members are key regulators of microtubule dynamics during mitosis and are therefore important for spindle assembly, kinetochore-MT attachments, and chromosome segregation. In addition, KIF24 and KIF2A are expressed at the centriole where they suppress primary cilia formation (Kobayashi et al., 2011; Miyamoto et al., 2015). In the nervous system, KIF2A is the only Kinesin-13 member expressed in postmitotic neurons where it depolymerizes MTs at the plus-end. Although early studies suggested that KIF2A is involved in the anterograde transport of cell organelles (Noda et al., 1995; Morfini et al., 1997), it is now established that KIF2A depolymerizes MTs, thereby regulating MT dynamics and triggering its catastrophe (Desai et al., 1999; Trofimova et al., 2018). In humans, KIF2A is a 706 amino acids (aa) protein composed of long N- and C-terminal regions, and a monomeric domain including a specific neck and the motor domain (Figure 1A). While the N- and C-terminal regions are involved in subcellular targeting and dimerization, the monomeric domain depolymerizes MTs. KIF2A forms dimers that attach to MTs, diffuse to the plus or minus ends, and bind two tubulin dimers. The neck, besides the KVD and the motor domain, induces drastic bending of a tubulin dimer triggering this dissociation from the protofilament (Figure 1B). This process is dependent on ATP binding to KIF2A. On the other hand, ATP hydrolysis is required to release the dissociated tubulin dimer from the KIF2A protein (Figure 1B; Trofimova et al., 2018). In neurons, MT dynamics is necessary to support morphological changes during neuronal development and maturation, such as neuron polarization and migration, axon guidance, and synapse formation (Kapitein and Hoogenraad, 2015). MTs are the railways for intracellular transport, and the specific MT organization and stabilization determine the binding of transport proteins, regulatory molecules, and cargo trafficking (Kelliher et al., 2019). In mature neurons, adaptative changes in response to internal and external stimuli are highly dependent on MT dynamics. KIF2A is required in the developing and mature brain and KIF2A mutations in humans are associated with different clinical features ranging from malformations of the cortical development (MCD) to epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder (Hatano et al., 2021). In this review, we will discuss new developments in our understanding of the role of KIF2A in the developing and mature brain as well as the impact of its mutations on neuronal circuitries function and maintenance.

Figure 1.

KIF2A structure and mechanism of action.

(A) Schematic illustration of human KIF2A domain organization. Red arrowheads point to human mutations described in previous reports. (B) Schematic representation depicting how KIF2A dimers (yellow) bind to MTs, progress towards the ends, and remove tubulin subunits from MT. ATP hydrolysis is required to release tubulin dimers from KIF2A. Created using Adode Illustrator.

Retrieval Strategy

Studies cited in this review were obtained from searching the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the following keywords: KIF2A, microtubules, kinesin-13, neurodevelopment, and neurodegeneration. The results were further screened by title and abstract, and only those studies focused on the function of Kinesin proteins in cell division and neuronal development and function were included. Studies cited in this review were published between 1976 and 2023. The majority of the selected studies (77% of all references) were published between 2010 and 2023.

The Debated Role of Kinesin Superfamily Protein 2A in Cell Division and Neurogenesis

Several studies, performed mostly in human cell lines and Xenopus eggs, have associated KIF2A with spindle MT dynamics. In mitotic cells, KIF2A localizes centrosomes in interphase, and in centrosomes and spindle midzone in anaphase and telophase (Ganem and Compton, 2004). KIF2A depolymerizes the MTs regulating the length and alignment of the central spindle and the MT poleward flux (Ganem et al., 2005; Uehara et al., 2013). Downregulation of KIF2A using siRNA in U2OS cells affects the formation of the spindle assembly, with 90% of cells displaying monopolar spindles in anaphase (Ganem and Compton, 2004). Blocking KIF2A activity using polyclonal antibodies in Xenopus egg extracts results in longer spindle MTs and monopolar spindles (Gaetz and Kapoor, 2004). In Xenopus animal caps, KIF2A is required for chromosome segregation and spindle assembly, and its loss prevents cell division and epiboly affecting gastrulation (Eagleson et al., 2015). Some studies emphasized the role of KIF2A in cell proliferation through MT depolymerization in primary cilia (Miyamoto et al., 2015; Zang et al., 2019). In hTERT-RPE1 cells, KIF2A is necessary for primary cilia disassembly in a growth-signal-dependent manner. However, most Kif2a-KO cells showed normal bipolar spindle formation and cell-cycle progression (Miyamoto et al., 2015). The function and localization of KIF2A in dividing cells are regulated by the Polo-like Kinase (Plk1) and Aurora A (Jang et al., 2009; Miyamoto et al., 2015). Plk1 phosphorylates KIF2A promoting its depolymerizing activity at the mother centriole and primary cilia disassembly (Miyamoto et al., 2015). The interaction between PlK1 and KIF2A is regulated by Wnt signaling (Bufe et al., 2021). KIF2A also can be negatively regulated by Aurora A phosphorylation (Jang et al., 2009).

In mice, electroporation of a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) of Kif2A in E13.5 embryos increased neuronal differentiation and promoted cell cycle exit (Sun et al., 2017). Acute expression of a human variant of KIF2A (p.His321Asp) in mouse embryos at E14.5 yielded the opposite effect with the production of more progenitors and fewer neurons. These differences in proliferation and cell cycle were ascribed to abnormalities in the spindle integrity and ciliogenesis (Broix et al., 2018). Knock-in mice expressing one copy of the same human variant (KIF2A+/H321D) displayed an altered subcellular localization of KIF2A in microtubules, suggesting that the variant has a dominant negative activity. Progenitors in the mutant cortex did not exhibit any difference in the mitotic index or percentage of apical progenitors, basal progenitors, or neurons. However, authors observed an increase in embryonic cell death in both, progenitors and newborn neurons (Gilet et al., 2020). Cortex-specific conditional knock-out mice (in which KIF2A was deleted in cortical progenitors at E9.5 using the Emx1-Cre mouse line) showed a normal proliferation of progenitors and no cell death. Their cortex was undisguisable from that of control littermates at birth. However, they displayed severe premature neurodegeneration (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b).

In summary, the role of KIF2A in cell division and neuronal proliferation is still not completely understood. While in vitro studies convincingly showed the role of KIF2A in spindle assembly, chromosome movement, and ciliogenesis, the results from studies in vivo are less conclusive. Many factors can account for such differences: a) The role of KIF2A in mitosis in cell culture could be different than in vivo due to external factors. b) A compensatory effect can occur in vivo as other members of the Kinesin-13 family (such as KIF2B, KIF2C/MCAK, and KIF24) have redundant functions in spindle assembly, chromosome separation, and KIF24 in primary cilia disassembly (Manning et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2011; Miyamoto et al., 2015). In line with this, the mitotic phenotype of KIF2A depletion in Xenopus can be rescued by human KIF2B (Eagleson et al., 2015). c) The discrepancy in the results of in vivo experiments could be the use of different approaches. Overexpression of a KIF2A variant by in utero electroporation without removing the endogenous protein can cause dose-dependent effects (Broix et al., 2018). The KIF2A variant introduced by in-utero electroporation or in the Knock-in mice (KIF2A+/H321D) s a missense mutation in the ATP binding region of the protein. This variant forms dimers with the endogenous KIF2A reducing the binding to MTs and altering the protein function (Broix et al., 2018; Gilet et al., 2020). Furthermore, proteomic analysis revealed that compared with the wild type, the variant has different interactors and therefore could have additional functions (e.g., dominant negative activity, gain of function, dose-dependent side effect) (Akkaya et al., 2021).

Kinesin Superfamily Protein 2A in Neuronal Migration

Neuronal migration of glutamatergic neurons in the developing cerebral cortex is radially oriented and follows an inside-out sequence. New neurons are generated in the ventricular zone (VZ) or subventricular zone (SVZ) from where they migrate in parallel to basal processes of radial glia to the appropriate cortical layer (Hakanen et al., 2019). KIF2A mutations were associated with several MCD, among which lissencephaly, pachygyria, and heterotopia are directly linked to defective radial migration of neurons (Poirier et al., 2013; Parrini et al., 2016; Tian et al., 2016; Cavallin et al., 2017). This is the case for instance of two de novo mutations namely, p.Ser317Asn and p.His321Pro that cause type 1 lissencephaly (Table 1; Cavallin et al., 2017). Mice expressing these variants exhibit abnormal radial migration of glutamatergic neurons and altered lamination of the cerebral cortex (Gilet et al., 2020). Radial migration starts when the shape of postmitotic neurons transforms from bipolar to multipolar. Defects in this first polarity transition result in periventricular heterotopia both in mice and humans (Kasioulis et al., 2017; Hakanen et al., 2019). Periventricular heterotopia is characterized by ectopically located nodules of neurons along the lateral ventricle walls (Lian and Sheen, 2015; Romero et al., 2018). However, no periventricular heterotopia has been reported in humans with KIF2A mutations or in knock-in mice bearing the human variants. The second polarity transition from multipolar to bipolar cell shape ends the multipolar migration in the upper intermediate zone (IZ) of the cerebral cortex. Migrating neurons in the upper IZ adhere again to radial glial processes and continue their migration into the cortical plate. Defects in the second multipolar-bipolar transition often lead to neuron accumulation in the upper IZ and subcortical band heterotopia (SBH) (Bai et al., 2003; Ohtaka-Maruyama and Okado, 2015). SBH is one of the KIF2A-related MCDs (Table 1; Poirier et al., 2013). Manipulation of KIF2A expression in mice increased the number of multipolar cells in the upper IZ and delayed radial migration (Homma et al., 2003; Broix et al., 2018; Gilet et al., 2020; Akkaya et al., 2021; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). In addition to the radial migration of glutamatergic neurons, KIF2A is involved in the tangential migration of interneurons (Broix et al., 2018; Hakanen et al., 2022; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). During brain development, GABAergic interneurons migrate tangentially from ventrally located ganglionic eminences into the cerebral cortex. Tangential migration also occurs postnatally where interneurons migrate from VZ/SVZ into the olfactory bulb via the rostral migratory stream. In absence of KIF2A, the velocity of migration of interneurons from the ganglionic eminences to the cerebral cortex is slower and the directionality is compromised (Broix et al., 2018; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022a). This does not dramatically affect the density of GABAergic interneurons but disrupts their positioning and connectivity, leading to abnormal behavior and increased susceptibility to epileptic seizures (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022a). The nearly normal density of interneurons despite defective tangential migration Kif2a conditional knock-out mice could be explained by compensatory mechanisms (e.g., reduced apoptosis) as one-third of interneurons undergo programmed cell death after arriving at their cortical in normal conditions (Southwell et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2018; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022a). Postnatally, interneurons also show reduced migration velocity and loss of directionality in the rostral migratory stream of Kif2a conditional knock-out mice. This results in interneuron accumulation at the proximal rostral migratory stream (adjacent to SVZ) and size reduction of the olfactory bulbs (Hakanen et al., 2022). It is yet to be discovered whether these defects in tangential migration contribute to the formation of MCDs or other neurodevelopmental disorders. Overall, KIF2A seems to affect the tangential migration of interneurons more severely than radial migration of cortical projection neurons, both at embryonic and postnatal stages. Radial and tangential migration shares the phenotype of slower neuronal migration, but only tangentially moving interneurons lose their directionality during migration. Thus, the differences between tangential and radial migration may be important in interpreting KIF2A function in neural migration (Broix et al., 2018; Hakanen et al., 2022; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022a). KIF2A-deficient interneurons show reduced velocity and lost directionality during their migration. Tangentially migrating interneurons move forwards with sequentially repeated leading processes extension, followed by centrosome movement, and finally translocation of soma. This migratory cycle is longer in Kif2a conditional knock-out mice compared with controls (Broix et al., 2018; Hakanen et al., 2022; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022a). A slower migration in Kif2a knock-out mice is caused by reduced velocities of leading process extension, centrosome movement, and soma translocation (Hakanen et al., 2022). The sequential migration cycle requires constant remodeling of the cell cytoskeleton, including dynamic reshaping of the MT cytoskeleton (Cooper, 2013). KIF2A-deficient interneurons show reduced MT growth rates during their migration. This slower MT growth speed could be the root cause of the longer migratory cycle by reducing leading process extension, centrosome, and soma velocity in KIF2A-deficient interneurons (Hakanen et al., 2022). MT cytoskeleton dynamics is also essential for directional cell migration (Watanabe et al., 2005; Cooper, 2013; Watanabe et al., 2015). The direction of neuronal movement is defined by the branching of the leading process tip. This branching facilitates migratory route finding of the interneurons by assisting in measuring attractants or repellent concentrations across the area (Cooper, 2013). MT assembly and disassembly rates can further modify both the extent and frequency of branching (Kappeler et al., 2006; Godin et al., 2012; Belvindrah et al., 2017; Nakamura et al., 2017). Kif2a knock-out mice show increased overall branching frequency and especially de novo branching formation from the soma (Hakanen et al., 2022). Regulators of MT organization, like KIF2A, are pivotal in establishing neuronal cell polarity and defining oriented neuronal migration by regulating leading process branching and formation (Arimura and Kaibuchi, 2007; Jossin, 2020). Polarity proteins which affect neuronal migration velocity and directionality with KIF2A interactions include, for example, CELSR3, CENPJ, CDK5, and PAK1 (Ogawa and Hirokawa, 2015; Ding et al., 2019; Kodani et al., 2020; Hakanen et al., 2022; Magliozzi and Moseley, 2021).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of seven patients with kinesin superfamily protein 2A single-nucleotide variants described in previous studies

| Mutation | AA substitution | Sex | Head circunference at birth | Head circunference at last evaluation | Developmental delay | Motor ability | Epilepsy | Cortical malfomations | Other signs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.961C>G | p.His321Asp | Female | 32 cm (–3.5 SD) | 43 cm (–5 SD) at 4 yr | Spastic tetraplegia | Bedridden | Early onset epilepsy | Posterior predominant pachygyria with subcortical band heterotopia and a thin corpus callosum | Intrauterine growth retardation, nystagmus, and scoliosis | Poirier et al., 2013; Cavallin et al., 2017 |

| c.950G>A | p.Ser317Asn | Female | 30 cm (–2.5 SD) | 44 cm (–4 SD) at 8 yr | Spastic tetraplegia | Bedridden | Early onset epilepsy | Posterior predominant pachygyria with a thick cortex and a thin corpus callosum | Nystagmus | Poirier et al., 2013; Cavallin et al., 2017 |

| c.950G>A | p.Ser317Asn | Female | 30.5 cm (–2.5 SD) | 40 cm (–4 SD) at 9 mon | Spastic tetraplegia, axial hypotonia | No development | Absent | Posterior agyria and frontal pachygyria | Strabismus | Cavallin et al., 2017 |

| c.962A>C | p.His321Pro | Male | 39.5 cm (0.3 SD) | 51.5 cm (–1 SD) at 8 yr | Spastic tetraplegia, axial hypotonia | No development | Neonatal seizures Poor seizure control | Posterior agyria and frontal pachygyria. Corpus callosum and cerebellum were normal. | Congenital nystagmus, cone/rod dysfunction, and scoliosis | Cavallin et al., 2017 |

| c.959C>T | p.Thr320Ile | Female | n.d. | 35.8 cm (–2.2 SD) at 2 mon | Central hypotonia, poor head control | No development | Early onset epilepsy | Posterior predominant pachygyria, dysplastic corpus callosum, and diminutive brainstem | Downgaze, nystagmus, microphthalmia, and PHPV with thin optic nerves | Tian et al., 2016 |

| c.1298C>A | p.Ser433Tyr | Male | 31 cm (–1.6 SD) | 42 cm (2.9 SD) at 1 yr | General hypotonia and psychomotor developmental delay | Muscle tone weak | Seizure onset at 4 years | Posterior dominant pachygyria, thick cortex, and a thin corpus callosum | Hatano et al., 2020 | |

| c.1363C>G | p.Leu455Val | Female | n.d. | Microcephaly at 5 yr | Global developmental delay, failure to thrive | n.d. | Early onset epilepsy | Delayed myelination, cerebral atrophy, thin corpus callosum | Costain et al., 2019 |

n.d.: Not described; PHPV: persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous.

Kinesin Superfamily Protein 2A in Maturation and Connectivity

MTs play important roles in morphological transitions during neuronal development such as neurite initiation, extension, pruning, and neuronal polarization and connectivity. For instance, for neuronal polarization, MT stabilization is a major factor in the induction of axon formation (Kapitein and Hoogenraad, 2015). In primary cultures of neurons, the accumulation of stable MTs in one of the neurites precedes axon specification. MT stabilization using the drug Taxol induces the formation of multiple axons in neurons (Witte et al., 2008). Therefore, the proportion between stable and dynamic MTs determines neuronal polarization. Given that KIF2A regulates MTs dynamics (Noda et al., 2012; Trofimova et al., 2018; Hakanen et al., 2022; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b), it is not surprising that KIF2A is required for proper neuronal polarization, neurite outgrowth, and pruning. Knocking out Kif2a in cultured neurons significantly increases not only the number of axons but also the number of primary dendrites (Homma et al., 2018; Akkaya et al., 2021; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). Kif2a-KO neurons exhibit overstable MT, with an increase of the tubulin PTM acetylation and polyglutamylation that account for axon specification (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). On the other hand, neurite pruning affects the number of dendrites in a neuron, and this process is dependent on MT disassembly (Rumpf et al., 2019). Accordingly, Kif2a deletion in dorsal root ganglion neurons prevents axonal pruning in vitro and results in a significant enhancement of the skin-innervating axons in vivo (Maor-Nof et al., 2013). The function of KIF2A in neuron morphology is regulated by the activity of kinases targeting different phosphorylation sites. For instance, KIF2A phosphorylation by ROCK2 enhances MT depolymerization reducing neurites extension and leading to round-shaped neurons. By contrast, PAK1-CDK5 kinase phosphorylates KIF2A reducing its activity and promoting neurites outgrowth in BDNF-stimulated neurons (Ogawa and Hirokawa, 2015). In line with that, axon collateral branches of cortical and hippocampal neurons with KIF2A-deletion are significantly longer compared to wild-type neurons (Homma et al., 2003; Noda et al., 2012; Ogawa and Hirokawa, 2015). The role of KIF2A in MT elongation in the axon is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase alpha (PIPKα) (Noda et al., 2012). PIPKα and KIF2A accumulate at the tips of neurites and partially colocalize at the growth cone where PIPKα enhances the MT-depolymerizing activity of KIF2A. Downregulation of PIPKα in hippocampal neurons increases the length of the axonal branches, a similar phenotype observed in Kif2a-KO neurons (Noda et al., 2012). In control conditions, MTs at the growth cone shrink or anchor when they collapse with the plasma membrane. In Kif2a-KO neurons, they continue to extend when they reach the cell edge and wander in the peripheral area (Homma et al., 2003; Noda et al., 2012). The size of the growth cone in Kif2a-KO hippocampal neurons is larger and accumulates more stable MTs (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). MT cytoskeleton is crucial for brain wiring. Guiding signals bind specific receptors at the growth cone of the projecting neuron and activate intracellular pathways that modulate MTs stabilization and assembly necessary for axon pathfinding (Sanchez-Huertas and Herrera, 2021). Surprisingly, only mild defects in axon guidance were associated with KIF2A ablation in mice. In cortex-specific conditional knockout mice, callosal axons cross the midline but fail to connect properly in the contralateral cortex. Corticospinal axons reach the pontine level and form the pyramidal decussation but fail to project to the spinal cord (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). These results suggest that KIF2A is more implicated in axon elongation rather than guidance. In the case of dendrites, KIF2A downregulation in cortical neurons using an shRNA does not change the dendritic length at 4 DIV (Akkaya et al., 2021). However, Kif2a-KO primary hippocampal neurons, after 15 DIV, exhibit shorter primary and secondary dendrites. Reduced cell size in Kif2a-deficient pyramidal neurons was confirmed in vivo by electrophysiological analysis in the Emx1-Kif2a cKO cortex (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). Moreover, MAP2, an MT-associated protein specifically located in dendrites, is aberrantly distributed in the cell body in KIF2A-deficient neurons both in vitro and in vivo. The layer I of mutant mice is significantly thinner compared with control mice suggesting a cell-autonomous role of KIF2A in dendritic arborization.

Kinesin Superfamily Protein 2A in Neurodegeneration and Neuroregeneration

In the mature brain, MTs play key roles in neuronal homeostasis and function. They are important for neurons to reorganize their cytoskeleton and adapt their morphology and plasticity in response to physiological challenges. MTs serve as highways for intracellular transport and in the control of local signaling events. Abnormalities in MT dynamics and composition are often associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Given that MT-associated proteins, tubulin-PTM, and severing proteins are directly related to MT dynamics, dysregulation of these factors can trigger neurodegeneration. For instance, an increase in MT stabilization in neurons, using the drug Taxol, reduces axonal transport and axonal length and triggers the degeneration of sensory axons (Gornstein and Schwarz, 2014). Mutation in the gene encoding the deglutamylase enzyme (CCP1), leads to excessive accumulation of tubulin polyglutamylation, a tubulin-PTM enriched in stable MTs (Mullen et al., 1976; Rogowski et al., 2010). Upregulated polyglutamylation impairs mitochondrial transport in the axon and triggers neurodegeneration (Magiera et al., 2018). Spastin, an MT-severing enzyme is also implicated in MT dynamics. Spastin-KO neurons exhibit axonal swelling and progressive degeneration, reduced synapse number, axonal transport, and excessive tubulin-polyglutamylation (Tarrade et al., 2006; Lopes et al., 2020). In humans, mutations in the Spastin gene (SPG4) are associated with hereditary spastic paraplegia, a neurological disorder characterized by the degeneration of the corticospinal tract.

Among the Kinesin-13 family, only KIF2A remains expressed in postmitotic neurons and is therefore the only member with roles in neuronal function and survival. KIF2A deletion impairs lysosome transport along the axon of hippocampal neurons in primary culture (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). These defects are most likely due to increased tubulin polyglutamylation and acetylation, enriched stable MTs, and decreased levels of EB3 and CLASP1. Tubulin polyglutamylation alters the affinity of Kif5 to bind MTs, a member of the Kinesin-1 subfamily implicated in the anterograde transport of some cell organelles including lysosomes (Lopes et al., 2020). Interestingly, Kif2a-KO hippocampal neurons have defects mainly in the anterograde movement of lysosomes in the axon, suggesting an impairment in kinesin-dependent transport. Deficits in lysosome transport and function are linked with neurodegeneration (Roney et al., 2022). Overstable MTs also account for defects in neuronal connectivity and synaptogenesis. Pyramidal neurons of the Kif2a-mutant cortex are not integrated into the cortical network, and they form less glutamatergic synapses in vitro. Therefore, specific deletion of KIF2A in mouse cortex triggers severe neurodegeneration that is not only due to aberrant development since KIF2A ablation in the fully mature brain, using a tamoxifen-inducible mutant mouse model (CamKII-Kif2a cKO), also causes neuronal loss (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b).

Investigation of a potential role for KIF2A in axon regeneration is still in its infancy. After spinal axon injury spinal cord, neurons display a dystrophic structure called retraction bulb. This structure is affected by the organization of the cytoskeleton (Blanquie and Bradke, 2018). Few studies aimed at developing efficient therapeutic strategies for injured neurons were carried out to understand differences in the activity of proteins regulating MT dynamics between growth cones and retraction bulbs. After spinal cord injury, KIF2A expression increases after 10 days in axons and mature oligodendrocytes adjacent to the injury site, suggesting an inhibitory role in axon branching, sprouting and regeneration (Seira et al., 2019). On the contrary, the downregulation of kinesin-13 proteins in C. elegans after injury promotes axonal regrowth (Ghosh-Roy et al., 2012). Additional studies are needed to address the role of KIF2A in MT dynamics in the retraction bulb and determine whether regulating the KIF2A activity could be instrumental in axon regeneration and treatment of neuropathic pain.

Kinesin Superfamily Protein 2A Human Mutations and Pathology

KIF2A forms homodimers that bind MTs. KIF2A mutations alter its subcellular distribution and turnover (Poirier et al., 2013). Mutant KIF2A forms dimers with the wild-type protein preventing binding to MT. KIF2A variant p.His321Asp reduces KIF2A depolymerizing activity and causes MT over stability (Gilet et al., 2020). Fibroblasts from patients or knock-in mice (KIF2A+/H321D) display an increased speed of EB3 comets, suggesting an enhanced MT polymerization (Gilet et al., 2020). Loss of KIF2A in neuroblasts using a conditional Kif2a-KO mouse line, causes an opposite effect with a reduced EB3 comets velocity (Hakanen et al., 2022).

In humans, KIF2A mutations result in MCD, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder (Poirier et al., 2013; Yuen et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2016; Cavallin et al., 2017; Costain et al., 2019; Hatano et al., 2021). The clinical features vary according to the mutated region (Figure 1A and Table 1). To date, six de novo missense mutations in the motor domain of KIF2A have been reported in patients with MCD (Figure 1A and Table 1). They all map to five different amino acids in the nucleotide-binding domain and the pocket of the KIF2A motor region. MCD includes microcephaly, lissencephaly, posterior agyria, pachygyria, and thin corpus callosum. Patients have developmental delay, neonatal or infantile epilepsy, motor dysfunction, and spastic tetraplegia (Table 1; Hatano et al., 2021).

Microcephaly in humans has been attributed to KIF2A’s role in cell division. However, as discussed above, loss of KIF2A in cortical progenitors does not trigger microcephaly in mice (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). By contrast, mice expressing a human variant exhibit early cell death in the cortex and microcephaly (Gilet et al., 2020). KIF2A mutations in the motor domain can lead to a gain of function in progenitor survival most probably by changing the protein partners (Akkaya et al., 2021). Alternatively, microcephaly could be secondary to cell death in young neurons given the known role of KIF2A in neuronal survival (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b).

Lissencephaly, another common feature of MCD patients, is a condition associated with defective neuronal migration. Transgenic and knock-in mice with human mutations p.Ser317Asn and p.His321Asp display neuron mispositioning and abnormal cortical lamination and these defects have been ascribed to defective radial migration (Broix et al., 2018; Gilet et al., 2020). Kif2a knock-out mice also exhibit defects in the radial migration of glutamatergic neurons causing altered neuron positioning in cortical layers (Homma et al., 2003; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022b). Specific deletion of KIF2A in cortical interneurons affects the migration and connectivity of inhibitory cortical interneurons in the cortex and mutant mice are more susceptible to epilepsy (Ruiz-Reig et al., 2022a). Therefore, epilepsy in humans with KIF2A mutations likely stems from an imbalance between excitation and inhibition due to aberrant cortical interneuron development and maturation. Besides neuronal migration, KIF2A has been involved in cancer cell invasion in many tissues including brain tumors (Li et al., 2019). For example, human gliomas show elevated KIF2A expression which supports glioma cells’ invasiveness and migration (Zhang et al., 2016). An additional missense mutation with a relatively milder phenotype has been described. The mutation (p.Leu455Val), located in the motor domain of KIF2A but outside the nucleotide-binding domain, was associated with childhood epilepsy, cerebral atrophy, delayed myelinization, and thin corpus callosum (Table 1; Costain et al., 2019). Furthermore, de novo deletions of the chromosome 5q12.1 region which encompasses KIF2A gene, are found in patients with intellectual disabilities and ocular anomalies (Jaillard et al., 2011). Lastly, rare variants and deregulation of KIF2A expression have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease in humans (Caceres and Gonzalez, 2020; Prokopenko et al., 2021).

Conclusion

KIF2A is essential for embryonic and postnatal brain development and maintenance. KIF2A-MT-dependent cell behaviors are highly spatiotemporal and context-dependent in nature. The different functions of KIF2A presumably rely on isoform expression and phosphorylation status. During brain development, regulation of MT dynamics by KIF2A is required for neuronal migration, polarization, and connectivity. KIF2A deregulations affect its function and trigger MCD in humans. However, it is not clear whether microcephaly observed in patients arises from defects in neurogenesis or premature cell death. Studies using conditional KO mice, in which KIF2A is deleted in a spatiotemporal manner, strongly support the idea of secondary microcephaly due to defects in MT dynamics and subcellular transport that affect neuronal maturation, connectivity, and survival. Further studies should strengthen the relationship between alterations in KIF2A, neurodevelopment, and neurodegeneration.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the following grants: Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS) PDR T0236.20, FNRS-Exellence of Science 30913351, and FNRS CDR J.0175.23 (to FT).

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Li CH; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Akkaya C, Atak D, Kamacioglu A, Akarlar BA, Guner G, Bayam E, Taskin AC, Ozlu N, Ince-Dunn G. Roles of developmentally regulated KIF2A alternative isoforms in cortical neuron migration and differentiation. Development. (2021);148:dev192674. doi: 10.1242/dev.192674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arimura N, Kaibuchi K. Neuronal polarity:from extracellular signals to intracellular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2007);8:194–205. doi: 10.1038/nrn2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai J, Ramos RL, Ackman JB, Thomas AM, Lee RV, LoTurco JJ. RNAi reveals doublecortin is required for radial migration in rat neocortex. Nat Neurosci. (2003);6:1277–1283. doi: 10.1038/nn1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belvindrah R, Natarajan K, Shabajee P, Bruel-Jungerman E, Bernard J, Goutierre M, Moutkine I, Jaglin XH, Savariradjane M, Irinopoulou T, Poncer JC, Janke C, Francis F. Mutation of the alpha-tubulin Tuba1a leads to straighter microtubules and perturbs neuronal migration. J Cell Biol. (2017);216:2443–2461. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanquie O, Bradke F. Cytoskeleton dynamics in axon regeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. (2018);51:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broix L, Asselin L, Silva CG, Ivanova EL, Tilly P, Gilet JG, Lebrun N, Jagline H, Muraca G, Saillour Y, Drouot N, Reilly ML, Francis F, Benmerah A, Bahi-Buisson N, Belvindrah R, Nguyen L, Godin JD, Chelly J, Hinckelmann MV. Ciliogenesis and cell cycle alterations contribute to KIF2A-related malformations of cortical development. Hum Mol Genet. (2018);27:224–238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bufe A, García Del Arco A, Hennecke M, de Jaime-Soguero A, Ostermaier M, Lin YC, Ciprianidis A, Hattemer J, Engel U, Beli P, Bastians H, Acebrón SP. Wnt signaling recruits KIF2A to the spindle to ensure chromosome congression and alignment during mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2021);118:e2108145118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2108145118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caceres A, Gonzalez JR. Female-specific risk of Alzheimer's disease is associated with tau phosphorylation processes:A transcriptome-wide interaction analysis. Neurobiol Aging. (2020);96:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavallin M, Bijlsma EK, El Morjani A, Moutton S, Peeters EA, Maillard C, Pedespan JM, Guerrot AM, Drouin-Garaud V, Coubes C, Genevieve D, Bole-Feysot C, Fourrage C, Steffann J, Bahi-Buisson N. Recurrent KIF2A mutations are responsible for classic lissencephaly. Neurogenetics. (2017);18:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s10048-016-0499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper JA. Cell biology in neuroscience:mechanisms of cell migration in the nervous system. J Cell Biol. (2013);202:725–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costain G, Cordeiro D, Matviychuk D, Mercimek-Andrews S. Clinical application of targeted next-generation sequencing panels and whole exome sequencing in childhood epilepsy. Neuroscience. (2019);418:291–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai A, Verma S, Mitchison TJ, Walczak CE. Kin I kinesins are microtubule-destabilizing enzymes. Cell. (1999);96:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding W, Wu Q, Sun L, Pan NC, Wang X. Cenpj regulates cilia disassembly and neurogenesis in the developing mouse cortex. J Neurosci. (2019);39:1994–2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1849-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eagleson G, Pfister K, Knowlton AL, Skoglund P, Keller R, Stukenberg PT. Kif2a depletion generates chromosome segregation and pole coalescence defects in animal caps and inhibits gastrulation of the Xenopus embryo. Mol Biol Cell. (2015);26:924–937. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-12-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ems-McClung SC, Walczak CE. Kinesin-13s in mitosis:Key players in the spatial and temporal organization of spindle microtubules. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2010);21:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaetz J, Kapoor TM. Dynein/dynactin regulate metaphase spindle length by targeting depolymerizing activities to spindle poles. J Cell Biol. (2004);166:465–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganem NJ, Compton DA. The KinI kinesin Kif2a is required for bipolar spindle assembly through a functional relationship with MCAK. J Cell Biol. (2004);166:473–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganem NJ, Upton K, Compton DA. Efficient mitosis in human cells lacking poleward microtubule flux. Curr Biol. (2005);15:1827–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh-Roy A, Goncharov A, Jin Y, Chisholm AD. Kinesin-13 and tubulin posttranslational modifications regulate microtubule growth in axon regeneration. Dev Cell. (2012);23:716–728. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilet JG, Ivanova EL, Trofimova D, Rudolf G, Meziane H, Broix L, Drouot N, Courraud J, Skory V, Voulleminot P, Osipenko M, Bahi-Buisson N, Yalcin B, Birling MC, Hinckelmann MV, Kwok BH, Allingham JS, Chelly J. Conditional switching of KIF2A mutation provides new insights into cortical malformation pathogeny. Hum Mol Genet. (2020);29:766–784. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godin JD, Thomas N, Laguesse S, Malinouskaya L, Close P, Malaise O, Purnelle A, Raineteau O, Campbell K, Fero M, Moonen G, Malgrange B, Chariot A, Metin C, Besson A, Nguyen L. p27(Kip1) is a microtubule-associated protein that promotes microtubule polymerization during neuron migration. Dev Cell. (2012);23:729–744. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gornstein E, Schwarz TL. The paradox of paclitaxel neurotoxicity:Mechanisms and unanswered questions. Neuropharmacology. (2014);76(Pt A):175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakanen J, Ruiz-Reig N, Tissir F. Linking cell polarity to cortical development and malformations. Front Cell Neurosci. (2019);13:244. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakanen J, Parmentier N, Sommacal L, Garcia-Sanchez D, Aittaleb M, Vertommen D, Zhou L, Ruiz-Reig N, Tissir F. The Celsr3-Kif2a axis directs neuronal migration in the postnatal brain. Prog Neurobiol. (2022);208:102177. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatano M, Fukushima H, Ohto T, Ueno Y, Saeki S, Enokizono T, Tanaka R, Tanaka M, Imagawa K, Kanai Y, Kato M, Shiraku H, Suzuki H, Uehara T, Takenouchi T, Kosaki K, Takada H. Variants in KIF2A cause broad clinical presentation;the computational structural analysis of a novel variant in a patient with a cortical dysplasia, complex , with other brain malformations 3. Am J Med Genet A. (2021);185:1113–1119. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.62084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homma N, Takei Y, Tanaka Y, Nakata T, Terada S, Kikkawa M, Noda Y, Hirokawa N. Kinesin superfamily protein 2A (KIF2A) functions in suppression of collateral branch extension. Cell. (2003);114:229–239. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homma N, Zhou R, Naseer MI, Chaudhary AG, Al-Qahtani MH, Hirokawa N. KIF2A regulates the development of dentate granule cells and postnatal hippocampal wiring. Elife. (2018);7:e30935. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaillard S, Andrieux J, Plessis G, Krepischi AC, Lucas J, David V, Le Brun M, Bertola DR, David A, Belaud-Rotureau MA, Mosser J, Lazaro L, Treguier C, Rosenberg C, Odent S, Dubourg C. 5q12.1 deletion:delineation of a phenotype including mental retardation and ocular defects. Am J Med Genet A. (2011);155A:725–731. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang CY, Coppinger JA, Seki A, Yates JR, 3rd, Fang G. Plk1 and Aurora A regulate the depolymerase activity and the cellular localization of Kif2a. J Cell Sci. (2009);122:1334–1341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.044321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jossin Y. Molecular mechanisms of cell polarity in a range of model systems and in migrating neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. (2020);106:103503. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2020.103503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapitein LC, Hoogenraad CC. Building the neuronal microtubule cytoskeleton. Neuron. (2015);87:492–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kappeler C, Saillour Y, Baudoin JP, Tuy FP, Alvarez C, Houbron C, Gaspar P, Hamard G, Chelly J, Metin C, Francis F. Branching and nucleokinesis defects in migrating interneurons derived from doublecortin knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet. (2006);15:1387–1400. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasioulis I, Das RM, Storey KG. Inter-dependent apical microtubule and actin dynamics orchestrate centrosome retention and neuronal delamination. Elife. (2017);6:e26215. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelliher MT, Saunders HA, Wildonger J. Microtubule control of functional architecture in neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. (2019);57:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi T, Tsang WY, Li J, Lane W, Dynlacht BD. Centriolar kinesin Kif24 interacts with CP110 to remodel microtubules and regulate ciliogenesis. Cell. (2011);145:914–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kodani A, Kenny C, Lai A, Gonzalez DM, Stronge E, Sejourne GM, Isacco L, Partlow JN, O'Donnell A, McWalter K, Byrne AB, Barkovich AJ, Yang E, Hill RS, Gawlinski P, Wiszniewski W, Cohen JS, Fatemi SA, Baranano KW, Sahin M, et al. Posterior neocortex-specific regulation of neuronal migration by CEP85L identifies maternal centriole-dependent activation of CDK5. Neuron. (2020);106:246–255.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Shu K, Wang Z, Ding D. Prognostic significance of KIF2A and KIF20A expression in human cancer:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) (2019);98:e18040. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lian G, Sheen VL. Cytoskeletal proteins in cortical development and disease:actin associated proteins in periventricular heterotopia. Front Cell Neurosci. (2015);9:99. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopes AT, Hausrat TJ, Heisler FF, Gromova KV, Lombino FL, Fischer T, Ruschkies L, Breiden P, Thies E, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Schweizer M, Schwarz JR, Lohr C, Kneussel M. Spastin depletion increases tubulin polyglutamylation and impairs kinesin-mediated neuronal transport, leading to working and associative memory deficits. PLoS Biol. (2020);18:e3000820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magiera MM, Bodakuntla S, Ziak J, Lacomme S, Marques Sousa P, Leboucher S, Hausrat TJ, Bosc C, Andrieux A, Kneussel M, Landry M, Calas A, Balastik M, Janke C. Excessive tubulin polyglutamylation causes neurodegeneration and perturbs neuronal transport. EMBO J. (2018);37:e100440. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magliozzi JO, Moseley JB. Connecting cell polarity signals to the cytokinetic machinery in yeast and metazoan cells. Cell Cycle. (2021);20:1–10. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2020.1864941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning AL, Ganem NJ, Bakhoum SF, Wagenbach M, Wordeman L, Compton DA. The kinesin-13 proteins Kif2a, Kif2b , and Kif2c/MCAK have distinct roles during mitosis in human cells. Mol Biol Cell. (2007);18:2970–2979. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maor-Nof M, Homma N, Raanan C, Nof A, Hirokawa N, Yaron A. Axonal pruning is actively regulated by the microtubule-destabilizing protein kinesin superfamily protein 2A. Cell Rep. (2013);3:971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miki H, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Analysis of the kinesin superfamily:insights into structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. (2005);15:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto T, Hosoba K, Ochiai H, Royba E, Izumi H, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Dynlacht BD, Matsuura S. The microtubule-depolymerizing activity of a mitotic kinesin protein KIF2A drives primary cilia disassembly coupled with cell proliferation. Cell Rep. (2015);10:664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morfini G, Quiroga S, Rosa A, Kosik K, Caceres A. Suppression of KIF2 in PC12 cells alters the distribution of a growth cone nonsynaptic membrane receptor and inhibits neurite extension. J Cell Biol. (1997);138:657–669. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullen RJ, Eicher EM, Sidman RL. Purkinje cell degeneration, a new neurological mutation in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1976);73:208–212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamura A, Tanaka R, Morishita K, Yoshida H, Higuchi Y, Takashima H, Yamaguchi M. Neuron-specific knockdown of the Drosophila fat induces reduction of life span, deficient locomotive ability, shortening of motoneuron terminal branches and defects in axonal targeting. Genes Cells. (2017);22:662–669. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noda Y, Sato-Yoshitake R, Kondo S, Nangaku M, Hirokawa N. KIF2 is a new microtubule-based anterograde motor that transports membranous organelles distinct from those carried by kinesin heavy chain or KIF3A/B. J Cell Biol. (1995);129:157–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noda Y, Niwa S, Homma N, Fukuda H, Imajo-Ohmi S, Hirokawa N. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase alpha (PIPKalpha) regulates neuronal microtubule depolymerase kinesin, KIF2A and suppresses elongation of axon branches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2012);109:1725–1730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107808109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogawa T, Hirokawa N. Microtubule destabilizer KIF2A undergoes distinct site-specific phosphorylation cascades that differentially affect neuronal morphogenesis. Cell Rep. (2015);12:1774–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohtaka-Maruyama C, Okado H. Molecular pathways underlying projection neuron production and migration during cerebral cortical development. Front Neurosci. (2015);9:447. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parrini E, Conti V, Dobyns WB, Guerrini R. Genetic basis of brain malformations. Mol Syndromol. (2016);7:220–233. doi: 10.1159/000448639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poirier K, Lebrun N, Broix L, Tian G, Saillour Y, Boscheron C, Parrini E, Valence S, Pierre BS, Oger M, Lacombe D, Geneviève D, Fontana E, Darra F, Cances C, Barth M, Bonneau D, Bernadina BD, N'guyen S, Gitiaux C, et al. Mutations in TUBG1, DYNC1H1, KIF5C and KIF2A cause malformations of cortical development and microcephaly. Nat Genet. (2013);45:639–647. doi: 10.1038/ng.2613. Erratum in: Nat Genet. 2013;45:962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prokopenko D, Morgan SL, Mullin K, Hofmann O, Chapman B, Kirchner R, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Amberkar S, Wohlers I, Lange C, Hide W, Bertram L, Tanzi RE. Whole-genome sequencing reveals new Alzheimer's disease-associated rare variants in loci related to synaptic function and neuronal development. Alzheimers Dement. (2021);17:1509–1527. doi: 10.1002/alz.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rogowski K, van Dijk J, Magiera MM, Bosc C, Deloulme JC, Bosson A, Peris L, Gold ND, Lacroix B, Bosch Grau M, Bec N, Larroque C, Desagher S, Holzer M, Andrieux A, Moutin MJ, Janke C. A family of protein-deglutamylating enzymes associated with neurodegeneration. Cell. (2010);143:564–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romero DM, Bahi-Buisson N, Francis F. Genetics and mechanisms leading to human cortical malformations. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2018);76:33–75. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roney JC, Cheng XT, Sheng ZH. Neuronal endolysosomal transport and lysosomal functionality in maintaining axonostasis. J Cell Biol. (2022);221:e202111077. doi: 10.1083/jcb.202111077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruiz-Reig N, Garcia-Sanchez D, Schakman O, Gailly P, Tissir F. Inhibitory synapse dysfunction and epileptic susceptibility associated with KIF2A deletion in cortical interneurons. Front Mol Neurosci. (2022a);15:1110986. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1110986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruiz-Reig N, Chehade G, Hakanen J, Aittaleb M, Wierda K, De Wit J, Nguyen L, Gailly P, Tissir F. KIF2A deficiency causes early-onset neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2022b);119:e2209714119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2209714119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rumpf S, Wolterhoff N, Herzmann S. Functions of microtubule disassembly during neurite pruning. Trends Cell Biol. (2019);29:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanchez-Huertas C, Herrera E. With the permission of microtubules:an updated overview on microtubule function during axon pathfinding. Front Mol Neurosci. (2021);14:759404. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.759404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seira O, Liu J, Assinck P, Ramer M, Tetzlaff W. KIF2A characterization after spinal cord injury. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2019);76:4355–4368. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03116-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Southwell DG, Paredes MF, Galvao RP, Jones DL, Froemke RC, Sebe JY, Alfaro-Cervello C, Tang Y, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Rubenstein JL, Baraban SC, Alvarez-Buylla A. Intrinsically determined cell death of developing cortical interneurons. Nature. (2012);491:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun D, Zhou X, Yu HL, He XX, Guo WX, Xiong WC, Zhu XJ. Regulation of neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation by Kinesin family member 2a. PLoS One. (2017);12:e0179047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tarrade A, Fassier C, Courageot S, Charvin D, Vitte J, Peris L, Thorel A, Mouisel E, Fonknechten N, Roblot N, Seilhean D, Dierich A, Hauw JJ, Melki J. A mutation of spastin is responsible for swellings and impairment of transport in a region of axon characterized by changes in microtubule composition. Hum Mol Genet. (2006);15:3544–3558. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tian G, Cristancho AG, Dubbs HA, Liu GT, Cowan NJ, Goldberg EM. A patient with lissencephaly, developmental delay, and infantile spasms, due to de novo heterozygous mutation of KIF2A. Mol Genet Genomic Med. (2016);4:599–603. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trofimova D, Paydar M, Zara A, Talje L, Kwok BH, Allingham JS. Ternary complex of Kif2A-bound tandem tubulin heterodimers represents a kinesin-13-mediated microtubule depolymerization reaction intermediate. Nat Commun. (2018);9:2628. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05025-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uehara R, Tsukada Y, Kamasaki T, Poser I, Yoda K, Gerlich DW, Goshima G. Aurora B and Kif2A control microtubule length for assembly of a functional central spindle during anaphase. J Cell Biol. (2013);202:623–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe T, Noritake J, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of microtubules in cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. (2005);15:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watanabe T, Kakeno M, Matsui T, Sugiyama I, Arimura N, Matsuzawa K, Shirahige A, Ishidate F, Nishioka T, Taya S, Hoshino M, Kaibuchi K. TTBK2 with EB1/3 regulates microtubule dynamics in migrating cells through KIF2A phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. (2015);210:737–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Witte H, Neukirchen D, Bradke F. Microtubule stabilization specifies initial neuronal polarization. J Cell Biol. (2008);180:619–632. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wong FK, Bercsenyi K, Sreenivasan V, Portales A, Fernandez-Otero M, Marin O. Pyramidal cell regulation of interneuron survival sculpts cortical networks. Nature. (2018);557:668–673. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0139-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yuen RK, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Merico D, Walker S, Tammimies K, Hoang N, Chrysler C, Nalpathamkalam T, Pellecchia G, Liu Y, Gazzellone MJ, D'Abate L, Deneault E, Howe JL, Liu RS, Thompson A, Zarrei M, Uddin M, Marshall CR, Ring RH, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of quartet families with autism spectrum disorder. Nat Med. (2015);21:185–191. doi: 10.1038/nm.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zang G, Jia J, Shi Y, Sharma T, Ratner A. Modeling and economic analysis of waste tire gasification in fluidized and fixed bed gasifiers. Waste Manag. (2019);89:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang X, Ma C, Wang Q, Liu J, Tian M, Yuan Y, Li X, Qu X. Role of KIF2A in the progression and metastasis of human glioma. Mol Med Rep. (2016);13:1781–1787. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]