Abstract

Twelve patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and with CD4 cell counts below 100 cells/μl received fluconazole daily (200 mg; five patients) or weekly (400 mg; seven patients) for fungal prophylaxis during a 6-month period. Oropharyngeal swabs were taken at regular intervals in order to detect colonization with Candida spp. All yeast isolates were examined with respect to the development over time of fluconazole resistance. Genetic diversity among the strains was assessed in order to discriminate between selection of a resistant subclone and patient recolonization. Genotyping was performed through random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. Specific site polymorphisms were assayed by tracking length variability in several microsatellite loci. Finally, to maximize resolution, one of these loci (ERK1) was analyzed by nucleotide sequencing. Although the number of strains analyzed was too small to allow statistical verification, it appeared that when fluconazole was given weekly, a smaller fraction of the strains showed diminished sensitivity than when it was given daily. Genetic analyses allowed three different scenarios to be discerned. Resistance development in an otherwise apparently unchanged strain was seen for 1 of the 12 patients. Clear strain replacement was observed for 3 of the remaining 11 patients. For all other patients minor differences were seen in either the RAPD genotype or the microsatellite allele composition during the course of treatment. In general, microsatellite sequence data is in agreement with data obtained by other methods, but occasionally within-patient heterogeneity is indicated. The present results show that during fluconazole treatment colonizing strains can remain identical, be replaced by clearly different strains, or undergo small changes. Within a patient there may be different levels of intrastrain variation.

The yeast Candida albicans is frequently encountered as an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised patients (e.g., see references 10 and 37). Although this ubiquitous yeast species is commonly found as a harmless commensal in normal hosts, a variety of factors, such as broad-spectrum antibiotics, abdominal surgery, malnutrition, and immune suppression, can allow this organism to invade normal defenses and cause direct yeast-attributable mortality (12). Studies of C. albicans strains isolated from persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have led to the suggestion that these strains may display more pathogenic features than strains isolated from otherwise healthy people (5). It has been suggested that certain strains of C. albicans may persist in HIV-infected persons living in a given geographic locale (31), but this has been questioned by other workers (17, 27). Occurrence of identical strains shared by HIV-infected and HIV-negative persons has also been demonstrated (18). Moreover, person-to-person transmission of fluconazole-resistant strains of C. albicans has been shown to occur (1).

The methodology for subspecies identification of Candida sp. strains includes chromosome visualization (3) and PCR-mediated analysis of DNA loci harboring variable numbers of tandem repeat regions (VNTRs, also known as mini- and microsatellites) (8, 11, 19). One example of a minisatellite in yeast is the Candida krusei repeated sequence 1 (CKRS-1) (8). In this case, the unit length is 165 bp and the repeat is located in the nontranscribed intergenic region of rRNA-encoding genes. Elements of the subset of VNTRs in which a certain short nucleotide motif (1 to 8 bases in length) is reiterated are known as microsatellites and are thought to evolve by slipped-strand mispairing events during replication (sometimes combined with recombination) (16). Polymorphisms in these motifs can be tracked by the use of repeat motif oligonucleotides as molecular probes (32) or by locus-specific PCR, which amplifies the variable regions (36). The usefulness for molecular typing of a compound microsatellite in the promoter region of the C. albicans elongation factor 3 (EF-3) gene was demonstrated in a recent study (7). The authors suggest that analysis of multiple VNTR loci may enable high-speed typing in the near future. The multitude of procedures currently available enable genetic identification studies to be performed with more than a single technique, rendering epidemiological interpretation reliable and detailed.

Treatment with oral azoles has greatly improved therapy of mucosal and invasive fungal infection, but an increasing prevalence of azole-resistant Candida sp. strains has been reported. The exact mechanisms by which fluconazole resistance develops are unknown. Several clinical factors have been suggested to increase the risk of azole resistance in mucosal candidiasis, including low CD4 cell counts, previous thrush infection, and prior opportunistic infections (25). The dose and schedule of fluconazole administration have been suggested to be important factors in the development of resistant candidiasis (2, 29, 37). To explore the effect of daily versus weekly fluconazole administration on the sensitivity of colonizing oropharyngeal strains of Candida spp. in HIV-infected patients, we collected baseline and 6-month cultures from patients entering a randomized prospective clinical trial. For all strains, random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis was performed (28, 37, 38); more specific changes were assayed by size and sequence determinations of microsatellites as found within defined genes (7, 11, 19). The relationship between resistance development and genome evolution in C. albicans is also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and strains.

Patients with CD4 cell counts of less than 100/μl and without active fungal infection were randomly assigned to receive either 200 mg of fluconazole/day or 400 mg of fluconazole/week as prophylaxis for deep fungal infections. Baseline and 6-month cultures were obtained from 12 patients, and by culture criteria all of the strains appeared to be C. albicans. These 12 patients had no clinically apparent fungal infection during the 6 months of follow-up. Swabs from the buccal, palatal, and lingual surfaces were streaked directly onto Sabouraud agar. Cultures were shipped at ambient temperature to a central lab (Fungus Testing Laboratory, Houston, Texas) for identification and fluconazole susceptibility testing as measured by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines (24). Several colonies were removed and stored in 15% glycerol medium at −80°C for later genotypic analysis.

DNA isolation.

Prior to DNA isolation strains were grown overnight at 30°C on solid Sabouroud dextrose medium. For RAPD analysis, DNA was isolated from a single colony of C. albicans cells according to the method of Boom et al. (6) with Zymolyase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and spheroplast lysis in a buffer containing 4 M guanidinium isothiocyanate. DNA was affinity purified with Celite (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium). The DNA concentration was adjusted to 100 ng/μl, and the solutions were stored at −20°C. For microsatellite amplification, a toothpick sample of cells was boiled for 10 min in 5% Chelex (5% [wt/vol] Chelex 100, 100/200 mesh in double-distilled water; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The mix was subsequently vortexed for 20 s and then centrifuged to settle the beads. DNA samples for PCR were drawn directly from these preparations (11).

RAPD analysis.

RAPD analysis was performed as described previously (37, 38) using Taq polymerase (Super-Taq; Sphaero Q, Leiden, The Netherlands) in a thermocycler (Biomed, Theres, Germany). The amplification program consisted of 2 min of predenaturation at 94°C followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 25°C, and 2 min at 74°C. Primers ERIC1 and ERIC2 (41) and 1026 and BG2 (35) were used in combinations in single tests (37). RAPD products were size separated on agarose gels, and the resulting banding patterns were scored for differences. Different types were assigned when more than a single band difference was observed. Single band differences are identified by superscript numbers for the genocode defined by capital lettering. In cases where overall genotypes were deduced, subtypes were not taken into consideration. Single band differences in multiple assays do not contribute to significant measures of genetic diversity (37, 38). (The same references can also be reviewed for matters of test reliability and reproducibility.)

Microsatellite analysis.

Microsatellites were analyzed essentially as described by Metzgar et al. (19). Briefly, PCR was performed in the presence of radiolabelled primers by using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and a Perkin-Elmer 2400 thermocycler (program: 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C). Samples were run on a polyacrylamide gel, and amplicons were detected by autoradiography. Amplicon patterns were identified on the basis of length differences among microsatellite-containing PCR products and were given numerical indices. The ERK1 locus was amplified from genomic DNA as described above and cloned into Escherichia coli with a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, N.M.). Sequencing of individual alleles was done with the Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio, and −40 primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reaction products were sequenced by using a standard ABI automated sequencer (model 373) (19). All alleles were sequenced in both directions, and in most cases enough amplicons were sequenced to obtain two, and often more, sequences from different clones of the same allele. In cases where multiple clones differed by single base identities, the consensus base, found in the majority of other alleles, was chosen.

RESULTS

Fluconazole treatment.

Fluconazole susceptibility data are noted in Table 1. A changes in susceptibility was considered significant if a fourfold or greater difference between the values for baseline and six-month isolates was seen. Three of five patients given daily fluconazole versus three of seven patients on the weekly regimen had fourfold changes (either increases or decreases) in susceptibility. Apparent loss of fluconazole susceptibility was present in two of five of the daily versus one of seven of the weekly fluconazole-treated patients.

TABLE 1.

Fluconazole MICs at 48 h for Candida sp. strains isolated from patients on daily or weekly medication

| Identification no.a | Isolation time | Fluconazole MIC | Fourfold change in susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected patients on 200 mg of fluconazole daily | |||

| 22-2435 | Baseline | 0.5 | |

| 22-2599 | 6 mo | 1.0 | No |

| 24-2445 | Baseline | 4.0 | |

| 24-2534 | 3 mo | 16.0 | Yes |

| 29-2436 | Baseline | <0.125 | |

| 29-2593 | 6 mo | 1.0 | Yes |

| 62-2437 | Baseline | 16.0 | |

| 62-2589 | 6 mo | 1.0 | Yes |

| 80-2525 | Baseline | >64.0 | |

| 80-2624 | 5 mo | >64.0 | No |

| HIV-infected patients on 400 mg of fluconazole weekly | |||

| 36-2518 | Baseline | 2.0 | |

| 36-2617 | 6 mo | 32.0 | Yes |

| 53-2442 | Baseline | 0.25 | |

| 53-2541 | 6 mo | <0.125 | Yes |

| 69-2514 | Baseline | >64.0 | |

| 69-2608 | 6 mo | 8.0 | Yes |

| 264-2535 | Baseline | 0.5 | |

| 264-2656 | 6 mo | 0.25 | No |

| 386-2607 | Baseline | 1.0 | |

| 386-2691 | 6 mo | 1.0 | No |

| 544-2621 | Baseline | 0.5 | |

| 544-2736 | 6 mo | 0.5 | No |

| 667-2686 | Baseline | 0.5 | |

| 667-2777 | 6 mo | 0.5 | No |

First two numbers in each identification number are the patient code; the last four numbers are the strain number.

Comparative molecular typing of C. albicans strains.

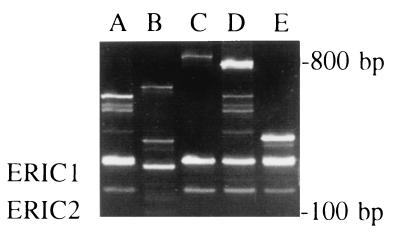

Two methods of genotyping were employed, and the experimental outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Figure 1 presents some examples of the data generated by RAPD analysis. In Table 2 the outcomes of the individual RAPD and microsatellite measuring assays are shown in combination with overall homology assessments based on the number of individual assays that show identity between pre- and posttreatment isolates of C. albicans. Of the 12 pairs of strains that were analyzed only 1 pair shows absolute identity between pre- and posttreatment genotype (strains 2436 and 2593 from patient 29). All possible combinations of RAPD and microsatellite data sets are found among the other pairs. Strains from patient 264 are microsatellite identical and RAPD diverse and those from patients 22, 24, and 667 are RAPD indistinguishable and microsatellite diverse. The posttreatment strain from patient 62 is nonreactive in the microsatellite-amplifying PCRs, whereas its RAPD code is widely different from the pretreatment strain characteristics as well. We suspected that the initial C. albicans colonizer had been replaced by another species of Candida. Ribosomal DNA sequencing and temperature-sensitive growth characteristics showed this to be Candida dubliniensis (19, 33). Strain 2442 from patient 53 was also shown to be C. dubliniensis by the same methods. Table 3 summarizes the data obtained by sequencing cloned amplicons derived from the ERK1 locus. In addition to the data shown, approximately 120 nucleotides upstream of the sequence depicted were confirmed to be essentially identical for all of the alleles except those which came from C. dubliniensis. Overall, seven different sequence compositions, differing mainly in the number of certain repeat motifs, could be discerned. Data were not collected for all of the paired strains, but extensive polymorphisms were documented between the paired isolates. Five of the eight pairs for which sequence data were collected gave sequences compatible with a stable diplotype over the treatment period (pairs from patients 29, 80, 36, 69, and 667). Patient 62 showed clear replacement of C. albicans with C. dubliniensis. For patients 386 and 22, partial concordance between the first and second samples was seen but more than two sequences were obtained for at least one of the samples. This heterogeneity suggests either within-patient polymorphisms or sequencing error. In the case of patient 667 it is noteworthy that the RAPD genotypes of both strains are identical although the microsatellite length profiles differ, implying that local changes have occurred in the yeast genome in the absence of gross alterations in the overall chromosome composition.

TABLE 2.

Survey of Candida sp. strain genetic characteristicsa

| Identification no. | Overall genome-scanning locus-specific genetic heterogeneity

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD type | % RAPD identity | Microsatellite type | % Microsatellite identity | ||||||||||||||

| HIV-infected patients on 200 mg of fluconazole daily | |||||||||||||||||

| 22-2435 | A | A | A | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 22-2599 | A | A | A | 100 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 83 |

| 24-2445 | A | B1 | B1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 24-2534 | A | B1 | B | 100 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 92 |

| 29-2436 | A | A | A | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 29-2593 | A | A | A | 100 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 100 |

| 62-2437 | A | B | B | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 62-2589 | C | C | E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 80-2525 | D | D | A3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 80-2624 | D | D | G | 67 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 83 |

| HIV-infected patients on 400 mg of fluconazole weekly | |||||||||||||||||

| 36-2518 | C | D | A2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 36-2617 | C | D | F | 67 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50 |

| 53-2442 | B | C | C | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 53-2541 | A | C | D | 33 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83 |

| 69-2514 | A | B | A1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 69-2608 | A2 | B | 50 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 83 | |

| 264-2535 | A1 | A | A | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 264-2656 | A | G | A | 67 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 386-2607 | A | A1 | A | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 386-2691 | A | J | A | 67 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| 544-2621 | A1 | E | G | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 544-2736 | A | J1 | A | 33 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 83 |

| 667-2686 | A3 | I | B1 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 667-2777 | A3 | I | B1 | 100 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83 |

The columns with the RAPD data display the codes obtained by three independent assays. Fingerprints were generated with the primer pairs ERIC1/ERIC2, ERIC2/1026, and ERIC2/BG2, from left to right, respectively (see Materials and Methods for more detail). RAPD subtypes, which are defined in Materials and Methods, are indicated by superscript figures. For determination of the overall RAPD consensus type, subtypes by the individual RAPD tests were disregarded. The following microsatellite loci (from left to right in the table) were examined for identity: ERK1, ERK1-2, 2NF1, 2NF1-2, EFG-2, EFG2-2, CCN2, CCN2-2, CPH2, CPH2-2, EFG1, and EFG1-2. The identification numbers are as defined in the footnote to Table 1.

FIG. 1.

RAPD analysis of C. albicans strains from HIV-infected patients on fluconazole treatment. Shown are all of the patterns obtained with the ERIC1-ERIC2 primer combination (types A to D). Type E is shown as a reference type and was obtained for a strain (2540) which is not included in either Table 1 or Table 2.

TABLE 3.

DNA sequences for the ERK1 allelles of some of the Candida sp. strainsa

| Identification no. | No. of clones/sequenced alleles | Allele | Sequence of allele |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected patients on the daily treatment regimen | |||

| 22-2435 | 5 | 237A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

| 2 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 2 | 234A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTANCGCTGCANCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 22-2599 | 1 | 234A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTANCGCTGCANCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 1 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 29-2436 | 2 | 246C | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCCGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 1 | 237A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 | |

| 29-2593 | 1 | 246C | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCCGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 62-2437 | 1 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 62-2589 | 3 | CdubA | (CAGGCT)1 (CAA)2CAGGCT(CAA)2CAG(GCA)7ACAACAGCAGCTAAC(GCT)5GGTGCTA(CTT)2 |

| 80-2525 | 4 | 249E | (CAGGCT)4 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)6 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

| 2 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 80-2624 | 1 | 249E | (CAGGCT)4 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)6 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

| 3 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| HIV-infected patients on the weekly treatment regimen | |||

| 36-2518 | 2 | 246D | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)2 CAAGCA(CAA)6 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTACAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 36-2617 | 2 | 249D | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)2 CAAGCA(CAA)7 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 1 | 246D | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)2 CAAGCA(CAA)6 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTACAGCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 69-2514 | 1 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 69-2608 | 2 | 246A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 |

| 386-2607 | 4 | 237A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

| 1 | 246B | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)8 CAGGCAGCAGCAGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 1 | 234A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTANCGCTGCANCTACTA(CTT)3 | |

| 386-2691 | 2 | 237A | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)1 CAAGCA(CAA)4 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

| 667-2686 | 2 | 249C | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)2 CAAGCA(CAA)6 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

| 667-2777 | 1 | 249C | (CAGGCT)3 (CAAGCT)2 CAAGCA(CAA)6 CAGGCAGCAGCCGCAGCCGCAGCAGCTAACGCTGCAGCTACTA(CTT)4 |

Data presented for strains from patients 29, 80, 36, 69, and 667 are all consistent with unchanged diplotypes (see also Results and Discussion). Strains 2607 and 2435 show more than one diplotype, suggesting within-patient heterogeneity. Identification numbers are as defined in the footnote to Table 1. Underlined, boldface characters identify single nucleotide mutations.

Colonization dynamics as measured by molecular typing.

The recolonization event in patient 62, where a C. albicans strain was replaced by an isolate of C. dubliniensis, also explains the drop in fluconazole resistance between the pre- and posttreatment strains. It is interesting to note that a strain with a lower resistance managed to replace a more-resistant strain from another species. This suggests that other factors besides susceptibility are important in the recolonization process. Strains from patients 22, 24, and 29 developed reduced fluconazole susceptibilities during treatment while maintaining identical RAPD and microsatellite genotypes. Apparently, resistant strains are selected from a pool of closely related but slightly differing genotypes initially occurring at low levels in these patients. The genetic effects of this evolutionary turnover could sometimes be seen in the microsatellite length data. For example, slight length changes were seen at some loci in strains from patients 22 and 24. These changes suggest rapid population turnover since a change in genotype requires most of the pathogen population to be replaced by the variant carrying the new allele.

The strains derived from the patients on the weekly dosage scheme identify a single patient (667) who was colonized by the same strain (RAPD- and microsatellite-determined genetic homogeneity) during the treatment period. Patients 36 and 69 may have been recolonized during the course of treatment, although this is not certain: the strains from patient 36 differ only in microsatellite lengths of nonsequenced sites. Moreover, the RAPD data for the two strains from patient 69 are different, while the ERK1 sequences are stable. Among the paired isolates from patients 53, 264, and 544, minor genetic changes are documented both by RAPD analysis and microsatellite analysis.

DISCUSSION

Susceptibility towards antifungals.

The results of the present study indicate that daily and weekly regimens of fluconazole prophylaxis can lead to changes in fluconazole MIC. Our sample size was too small to speculate as to which regimen might lead to a greater propensity to develop resistance. This prohibits detailed discussions on the statistical significance of our data. However, Table 1 illustrates the tendency towards more frequent increases in resistance in the case of daily antifungal treatment. Molecular typing reveals that even if the MICs of the pre- and posttreatment isolates are similar, genetic change can be observed at the DNA level, as assessed either by RAPD analysis or microsatellite techniques. In nearly all pairs of strains (except strains from patient 29) genetic change could be observed: 8 of 12 pairs could be discriminated on the basis of RAPD analysis, whereas 10 of 12 pairs showed differences when the microsatellite alleles were studied. It should be emphasized that determination of pre- and posttreatment drug susceptibilities of pathogens requires accompanying genotyping of the strains in order to distinguish between recolonization by a new strain and the development or selection of resistant (sub)strains from the pool of pathogens initially present as a population within the individual.

C. albicans epidemiology in AIDS patients.

Treatment with antifungals affects the population structure of C. albicans inhabiting particular human body sites. Several studies address this subject and various (re)colonization patterns have been demonstrated. Entire populations may be replaced by a different strain of C. albicans or another species (2, 4, 17, 27). In several cases development of resistance to antifungals was observed, without major changes in the genetic profiles determined for the yeast strain, indicating selection of a resistant subclone (2, 17, 20, 27). A precise definition of the phenomenon of clonal replacement is generally missing from the literature describing resistance development. Also, the degree of variability detected between pre- and posttreatment C. albicans isolates strongly depends on the molecular procedure used and on the individual patient. In previous studies, patients often revealed widely differing colonization dynamics. Our present study confirms previous findings of rapid strain evolution and variable colonization dynamics. In general, a relatively rapid turnover of population composition and frequent clonal replacement or a shift in the predominant clonal type leading to repopulation of the patient by a variant of the original strain were observed. It has to be emphasized that in many cases distinguishing between recolonization and strain selection is difficult. In the present communication we consider recolonization a likely event in cases where at least two of three RAPD assays gave rise to the definition of separate types (not subtypes; see Table 2, patients 62, 53, and 544).

VNTR polymorphisms among C. albicans strains.

Various regions in the chromosomes of C. albicans can be used for tracking DNA variation in the course of infection or colonization of given individuals. Analysis of the data shown in the present communication indicates that the intrinsic instability of C. albicans VNTR sites in general and the ERK1 locus in particular (see Table 3) may be a major pitfall to epidemiological applications: the speed of the molecular clock by which these loci evolve may be too high, even within the usually limited time frame in which epidemiological research takes place. In vivo evolution of the microsatellite in the EF-3 gene has not been studied yet (7); the outcome of these studies may clarify its usefulness as an epidemiological molecular marker. It is notable that all microsatellite loci used in this study were shown to be stable over 8 weeks of serial culture (18a), suggesting either that the in vivo environment may destabilize these loci or that changes in microsatellites between the first and second isolates may represent clonal replacement by preexisting rare genotypes within the original population.

As demonstrated in the present study, the different procedures monitor different types of molecular changes (chromosomal rearrangements, repeat expansion or contraction, base substitutions, etc.) which take place at different evolutionary clock speeds. Establishing the monitoring efficacies of the different methods is of prime importance for estimating the value of short- or long-term follow-up of clinical strains. RAPD analysis was recently suggested to be an adequate method for monitoring overall genome flexibility in C. albicans, and parity with other genome-scanning protocols was assessed (28). The following provisional conclusions can be based on the data shown in Table 2: daily fluconazole treatment leads to selection, RAPD patterns are rather well conserved, and evolution of the VNTRs can be observed (see references 21 and 22 for mechanistic information).

Contingency behavior in C. albicans.

The present study demonstrates that C. albicans populations inhabiting the human body are subject to frequent change; the causative selection and/or induction events may be clinically relevant processes since they reflect the capacity of a C. albicans strain to respond to environmental signals. This type of contingency behavior has been associated with VNTR- or microsatellite-mediated modulation of gene expression in different species of bacteria (23, 26, 30, 39, 40). Since most of the microsatellites assayed in the present study are located in functional genes, encoding primarily polyglutamine tracts in proteins associated with gene regulation (13, 14), potential functional aspects of the observed microsatellite polymorphisms warrant further studies. The most prevalent C. albicans genotype in a population of cells changes from time to time, and a primary question is whether, in patients not treated with fluconazole, similar variability can be detected or whether the effect documented in the present communication is a direct consequence of antifungal treatment. The fact that the strains analyzed inhabit an immunocompetent human body complicates the drawing of definite conclusions at this stage. It is most fascinating to note that despite a high degree of genetic flexibility in the VNTRs studied here, overall genome composition may be quite well conserved. Population-based studies have shown clear genetic differences between European and American isolates. Strains in the two groups cluster among but not between each other (9), suggesting that despite genomic flexibility, group identity is maintained. This further emphasizes that different evolutionary clock speeds are generating divergence at different genetic and geographical levels of analysis (14, 15, 34).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barchiesi F, Hollis R J, del Poeta M, McGough D A, Scalise G, Rinaldi M G, Pfaller M A. Transmission of fluconazole resistant Candida albicans between patients with AIDS and oropharyngeal candidiasis documented by pulsed field electrophoresis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:561–564. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bart-Delabesse E, Boiron P, Carlotti A, Dupont B. Candida albicans genotyping in studies with patients with AIDS developing resistance to fluconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2933–2937. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2933-2937.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton R C, van Belkum A, Scherer S. Stability of karyotype in serial isolates of Candida albicans from neutropenic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:794–796. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.794-796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berenguer J, Diaz-Guerra T, Ruiz-Diez B, Bernaldo de Quiros J C L, Rodriguez-Tudela J L, Martinez-Suarez J V. Genetic dissimilarity of two fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains causing meningitis and oral candidiasis in the same AIDS patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1542–1545. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1542-1545.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerlin P, Boerlin-Petzold F, Durussel C, Addo M, Pagani J L, Chave J P, Bille J. Cluster of oral atypical Candida albicans isolates in a group of human immunodeficiency virus-positive drug users. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1129–1135. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1129-1135.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boom R, Sol C J A, Salimans M M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M E, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bretagne S, Costa J M, Besmond C, Carsique R, Calderone R. Microsatellite polymorphism in the promoter sequence of the elongation factor 3 gene of Candida albicans as the basis for a typing system. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1777–1780. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1777-1780.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlotti A, Chaib F, Couble A, Bourgeois N, Blanchard V, Villard J. Rapid identification and fingerprinting of Candida krusei by PCR-based amplification of the species-specific repetitive polymorphic sequence CKRS-1. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1337-1343.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemons K V, Feroze F, Holmberg K, Stevens D A. Comparative analysis of genetic variability among Candida albicans isolates from different geographic locales by three genotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1332–1336. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1332-1336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz-Guerra T M, Martinez-Suarez J, Laguna F, Rodriguez-Tudela J L. Comparison of four molecular typing methods for evaluating genetic diversity among Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients with oral candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:856–861. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.856-861.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field D, Eggert L, Metzgar D, Rose R, Wills C. Use of polymorphic short and clustered coding-region microsatellites to distinguish strains of Candida albicans. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;15:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser V J, Jones M, Dunkel J, Storfer S, Medoff G, Dunagan W C. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: epidemiology, risk factors and predictors of mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:414–421. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber H P, Seipel K, Georgiev O, Hoefferer M, Hug M, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. Transcriptional activation modulated by homopolymeric glutamine and proline stretches. Science. 1994;263:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.8303297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gostout B, Liu Q, Sommer S S. “Cryptic” repeating triplets of purines and pyrimidines (cRRY(i)) are frequent and polymorphic: analysis of coding cRRY(i) in the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and TATA-binding protein (TBP) genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:1182–1190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenski R E, Sniegowski P D. Directed mutations slip-sliding away? Curr Biol. 1995;5:97–99. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levinson G, Gutman G A. Slipped strand mispairing: mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:203–221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lischewski A, Ruhnke M, Tennagen I, Schonian G, Morschhauser J, Hacker J. Molecular epidemiology of Candida isolates from AIDS patients showing different fluconazole resistance profiles. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:769–771. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.769-771.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lupetti A, Guzzi G, Paladini A, Swart K, Campa M, Senesi S. Molecular typing of Candida albicans in oral candidiasis: karyotype epidemiology with human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients in comparison with that with healthy carriers. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1238–1242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1238-1242.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Metzgar, D. Unpublished results.

- 19.Metzgar, D., D. Field, R. Haubrich, and C. Wills. Sequence analysis of a compound coding region microsatellite in Candida albicans resolves homoplasies and provides a high-resolution tool for genotyping. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Millon L, Manteaux A, Reboux G, Drobacheff C, Monod M, Barale T, Michel-Briand Y. Fluconazole-resistant recurrent oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients: persistence of Candida albicans strains with the same genotype. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1115–1118. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1115-1118.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moxon E R, Rainey P B. Ecology of pathogenic bacteria. Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences, Second Series, no. 96. 1995. Pathogenic bacteria: the wisdom of their genes; pp. 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moxon E R, Rainey P B, Nowak M A, Lenski R E. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Curr Biol. 1996;4:24–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy G L, Connell T D, Barritt D S, Coomey M, Cannon J G. Phase variation of gonococcal protein II: regulation of gene expression by slipped strand mispairing of a repetitive DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;56:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: proposed standards. Document M27-P. 12, no. 25. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomura J, Ruskin J. Failure of therapy with fluconazole for candidal endophthalmitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:888–889. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peak I R A, Jennings M P, Hood D W, Bisercic M, Moxon E R. Tetrameric repeat units associated with virulence factor phase variation in Haemophilus also occur in Neisseria spp. and Moraxella catarrhalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:109–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfaller M A, Rhine-Chalberg J, Redding S W, Smith J, Farinacci G, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Variations in fluconazole susceptibility and electrophoretic karyotype among oral isolates of Candida albicans from patients with AIDS and oral candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:59–64. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.59-64.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pujol C, Joly S, Lockhart S R, Noel S, Tibayrenc M, Soll D R. Parity among the randomly amplified polymorphic DNA method, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and Southern blot hybridization with the moderately repetitive DNA probe Ca3 for fingerprinting Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2348–2358. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2348-2358.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richet H M, Andremont A, Tancrede C, Pico J L, Jarvis W R. Risk factors for candidemia in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:211–215. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riesenfeld C, Everett M, Piddock L J V, Hall B G. Adaptive mutations produce resistance to ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2059–2060. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid J, Odds F C, Wiselka M J, Nicholson K G, Soll D R. Genetic similarity and maintenance of Candida albicans strains from a group of AIDS patients demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:935–941. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.935-941.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan D J, Bennett D, Henman M, Harwood P, Flint S, Mulcahy F, Shanley D, Coleman D. Oligonucleotide fingerprinting of isolates of Candida species other than C. albicans and of atypical Candida species from human immunodeficiency virus-positive and AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2124–2133. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2124-2133.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan D J, Westerneng T J, Haynes K A, Bennett D E, Coleman D C. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology. 1995;141:1507–1521. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tautz D, Schlotterer C. Simple sequences. Curr Biol. 1994;4:832–837. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Belkum A, Bax R, Peerbooms P, Goessens W H F, van Leeuwen N, Quint W G V. Comparison of phage typing and DNA fingerprinting by PCR for discrimination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:798–803. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.798-803.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Belkum A, Scherer S, van Leeuwen W, Willemse D, van Alphen L, Verbrugh H. Variable number of tandem repeats in clinical strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5017–5027. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5017-5027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Belkum A, Melchers W, de Pauw B E, Scherer S, Quint W, Meis J F G M. Genotypic characterization of sequential Candida albicans isolates from fluconazole-treated neutropenic patients. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1062–1070. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Belkum A, Mol W, van Saene R, Ball L M, van Velzen D, Quint W G V. PCR-mediated genotyping of Candida albicans from bone marrow transplant patients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1994;13:811–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Ende A, Hopman C T P, Zaat S, Essink B B O, Berkhout B, Dankert J. Variable expression of class 1 outer membrane protein in Neisseria meningitidis is caused by variation in the spacing between the −10 and −35 regions of the promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2475–2480. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2475-2480.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Ham S M, van Alphen L, Mooi F R, van Putten J P M. Phase variation of Haemophilus influenzae fimbriae: transcriptional control of two divergent genes through a variable combined promoter region. Cell. 1993;73:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]