Abstract

We present a progress report towards Bactobolin A and C4-epi-Bactobolin A. Sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker cyclization followed by a Tsuji-Wacker ketone synthesis furnishes a key tricyclic intermediate which we hypothesize can be elaborated into C4-epi-Bactobolin A. Epimerization of one of the stereocenters of this compound furnishes an intermediate which we hypothesize can be elaborated into Bactobolin A.

Keywords: Aza-Wacker cyclization, Total synthesis, Antibiotics

The rise of antimicrobial resistance has motivated the search for new classes of antibiotics [1,2]. Synthetic exploration of antibiotic scaffolds is a proven strategy for enriching the therapeutic pipeline [3–7]. Our laboratory has a programmatic focus on the development of new reactions for the syntheses of antibiotics with mechanisms of action distinct from ones which are FDA-approved [8–10]. Bactobolin A is one such antibiotic which we were motivated to pursue, both for its broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and for its complex, functional-group rich scaffold (Fig. 1A) [11,12]. Bactobolin A inhibits bacterial protein translation by binding to the L2 protein of the bacterial ribosome 50s subunit, which is an unusual location for antibiotic interactions [13,14]. To date, there exists one racemic synthesis [15–17] (Weinreb) and one enantiospecific synthesis [18] (Švenda) of Bactobolin A (Fig. 1B). Creative albeit unfinished approaches to Bactobolin A have been furnished by Danishefsky [19], Fraser-Reid [20], and Ward [21].

Fig. 1.

(A) Bactobolin A is a potent antibiotic, and there are many analogues which are unexplored. (B) Literature approaches to installing the C4 nitrogen with our own.

There are only a few reports on the syntheses and analyses of Bactobolin A derivatives [22–24]. Existing reports have focused on modifying Bactobolin A side chains rather than fundamentally altering the core scaffold. Based on our previous efforts with a model compound [10], we envisioned a synthesis of Bactobolin A in which our laboratory’s sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker cyclization [8] would be used to install the 1,3-amino alcohol structural element. However, this model compound lacked the C7 hydroxyl group found in Bactobolin A, and it was unclear how the presence of this additional functional group would affect the yield and selectivity of the aza-Wacker cyclization. If our route was successful, we envisioned using it to access unnatural isomers of Bactobolin A (Fig. 1) which would be difficult or impossible to access by chemical degradation or by semisynthetic studies with fermentation-derived natural product. Here, we describe our synthesis of key tricyclic intermediates using this strategy, which we envision can later be elaborated into Bactobolin A and interesting analogues.

In our retrosynthetic analysis (Fig. 2), we envisioned nucleophilic opening of activated oxathiazinane heterocycle B to set the C6 stereocenter of Bactobolin A. Tricyclic intermediate B would be synthesized by addition of into ketone C followed by a Weinreb-inspired alkoxycarbonylation reaction [17]. Ketone C would be prepared from sulfamate D using two sequential Wacker oxidations. The first would be our laboratory’s sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker cyclization reaction followed by a Tsuji-Wacker ketone synthesis [25]. We planned to prepare sulfamate D using enone E, itself accessible from D-(−)-Quinic acid, a commercially available chiron.

Fig. 2.

Our retrosynthetic analysis incorporates two Wacker oxidation steps.

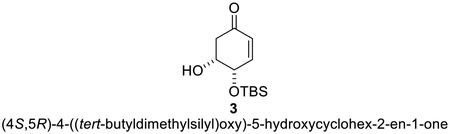

Our synthesis commenced by transforming (D)-(−)-Quinic acid into enone 1 using our laboratory’s previously disclosed optimization of literature precedent (Fig. 3) [10]. The acetonide group was removed by treatment of 1 with aqueous acetic acid at room temperature. Preferential TBS protection of the allylic alcohol was effected using TBSCl/imidazole/DMAP in DMF.

Fig. 3.

Opening sequence.

Our first major challenge in this synthesis was installation of the all-syn stereotriad of 5. We hypothesized that diastereoselectivity in this conjugate addition may be achievable if addition were directed by the unprotected homoallylic alcohol of 3. There is literature precedent for diastereoselectivity in conjugate additions in which an allylic alcohol serves as a stereocontrol element, but, to our knowledge, very little is known about chelation to a homoallylic alcohol [26,27]. Accordingly, many conditions were tested (Fig. 4). Early experiments with organocuprates yielded intractable mixtures of diastereomers. A positive result came upon switching to organoaluminum reagents, prepared from reaction of the corresponding Grignard reagent with AlCl3. With three equivalents of tri((Z)-prop-1-en-1-yl)aluminum, we isolated desired product in 10% yield, but, more importantly, as a single diastereomer (Fig. 4, Entry 1). As equivalents of tri((Z)-prop-1-en-1-yl)aluminum increased, so too did the yield (Fig. 4, Entries 2–4). More than 10 equivalents of tri((Z)-prop-1-en-1-yl)aluminum was deleterious however (Fig. 4, Entry 5). Dropping the start temperature of the reaction from 0 °C to −20 °C was beneficial (Fig. 4, Entry 6), but there was no benefit to further decreasing the temperature to −78 °C (Fig. 4, Entry 7). To confirm the stereochemistry of 5, we prepared its acetate derivative, assigned the shifts of the salient protons using 2-D NMR spectroscopy, and saw a strong transannular NOE enhancement between these protons (see Supporting Information for further details).

Fig. 4.

Conjugate addition directed by a homoallylic alcohol.

Treatment of 5 with TBAF removed the TBS group (Fig. 5). The homoallylic alcohol was then selectively protected using TBSCl/NEt3, and we hypothesize that steric factors underlie selectivity. Ketone 7 was converted into acetonide 8 with trimethyl orthoformate, ethylene glycol, and catalytic p-toluenesulfonic acid. Sulfamoylation of 8 proceeded upon treatment with ClSO2NH2 in DMA.

Fig. 5.

Synthesis of the aza-Wacker cyclization precursor.

The next challenge of the synthesis was optimization of the key sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker cyclization reaction. Despite their remarkable utility for site-selective amination, aza-Wacker reactions are rarely used as key steps in the syntheses of complex molecules [28,29]. Tethered aza-Wacker reactions are particularly powerful because a pre-existing C–N bond is no longer required to form a new one. Our laboratory has a programmatic focus on increasing the prominence of tethered aza-Wacker technology in complex molecule syntheses, and our pursuit of Bactobolin A provided a perfect opportunity to further develop the sulfamate-tethered variant of this chemistry. With 15 mol% of Pd(OAc)2 and 1 equivalent of Cu(OAc)2, cyclized product was isolated in a 20% yield (Fig. 6A, Entry 1). Increasing the loading of Pd(OAc)2–25 mol% led to an increase in product yield to 45% (Fig. 6A, Entry 2). While further [Pd] loading was deleterious (Fig. 6A, Entry 3), increasing the reaction time from 16 h to 24 h was markedly beneficial (Fig. 6A, Entry 4). The reaction yield plateaued at 36 h (Fig. 6A, Entries 5–6). Based on previous work with a model compound [10], we hypothesized that the newly formed C4 stereocenter was epimeric to that of natural Bactobolin A. Further experimentation (vide infra) would confirm this suspicion. The exquisite diastereoselectivity of this reaction warrants further discussion (Fig. 6B). We hypothesize that minimization of unfavorable steric clashing between the pendant (Z)-alkene and the cyclohexane ring forces 9 to adopt the specific conformation which allows for 10 to form selectively.

Fig. 6.

(A) Optimization of the sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker cyclization reaction.

Tsuji-Wacker oxidation of alkene 10 into ketone 11 proceeded in excellent yield using PdCl2/CuCl in aqueous DMF (Fig. 7). We made many attempts to crystallize 11, but, in most cases, we were unsuccessful. In one instance, high quality crystals formed from slow evaporation from acetone in a scintillation vial open to air (~14 days). However, to our surprise, the crystals were of imine 12, which we hypothesize formed from slow oxidation of 11. Interestingly, we do not observe formation of 12 during the Tsuji-Wacker oxidation step.

Fig. 7.

Tsuji-Wacker oxidation and unexpected imine formation during a crystallization event.

In the Weinreb synthesis of Bactobolin A, the CHCl2 moiety was diastereoselectively introduced via addition of Cl2CHLi in the presence of CeCl3 at −100 °C.17 We hypothesized that finding alternate conditions for introduction of the CHCl2 group may contribute to the future scalability and reproducibility of our synthesis. To this end, we tested conditions developed by Mioskowski for the addition of into ketones [30]. To our surprise, rather than forming 13, these conditions led to inversion of the C4 stereocenter; we note that this stereochemistry matches that found in natural Bactobolin A. A crystal structure of 14 allowed us to confirm product identity and stereochemistry unambiguously (Fig. 8). Furthermore, we were then able to assign the stereochemistry of 11 by analogy (see Supporting Information for further details).

Fig. 8.

Conditions which should allow for CHCl2 addition into the ketone actually led to epimerization of the nitrogen stereocenter.

We envision that 11 and 14 will serve as key intermediates for syntheses of C4-epi-Bactobolin A and Bactobolin A. Some important future steps will be diastereoselective introduction of the CHCl2 functional group, formation of the lactone, and oxathiazinane ring opening. We shall continue forward with these goals in mind.

1. Experimental section

General Considerations: All reagents were obtained commercially unless otherwise noted. Solvents were purified by passage under 10 psi N2 through activated alumina columns. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific™ Nicolet™ iS™5 FT-IR Spectrometer; data are reported in frequency of absorption (cm−1). 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 400, 500, or 600 MHz. Data are recorded as: chemical shift in ppm referenced internally using residual solvent peaks, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet or overlap of nonequivalent resonances), integration, coupling constant (Hz). 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 101 MHz or at 126 MHz. Exact mass spectra were recorded using an electrospray ion source (ESI) either in positive mode or negative mode and with a time-of-flight (TOF) analyzer on a Waters LCT PremierTM mass spectrometer and are given in m/z. TLC was performed on pre-coated glass plates (Merck) and visualized either with a UV lamp (254 nm) or by dipping into a solution of KMnO4–K2CO3 in water followed by heating. Flash chromatography was performed on silica gel (230–400 mesh) or Florisil (60–100 mesh).

2. Synthesis and characterization

Compound 1 was synthesized from D-(−)-Quinic acid according to a previously reported sequence [10].

2.1. Synthesis of compound 2

A 100 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a stir bar, 1 (2 g, 11.9 mmol, 1 equiv.), and 80% aqueous acetic acid (40 mL) at room temperature. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. Following this time, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified through column chromatography on Florisil by eluting with hexane/ethyl acetate (20:80) to afford of 2 (1 g, 7.8 mmol, 66%) as a white semi-solid.

2 is a known compound [31].

2.2. Synthesis of compounds 3 and 4

A 100 mL round-bottom flask was charged with 2 (1.00 g, 7.81 mmol, 1 equiv.), imidazole (0.584 g, 8.59 mmol, 1.1 equiv.), and anhydrous DMF (15 mL, Reaction Concentration = 0.5 M). The reaction flask was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath. TBSCl (1.30 g, 8.63 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) and DMAP (190 mg, 1.56 mmol, 0.2 equiv.) were sequentially added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at 0 °C. Following this time, the ice-water bath was removed, and the reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature over a period of 3 h. Following this time, the reaction was diluted with EtOAc (30 mL) and chilled H2O (50 mL) and transferred to a separatory funnel. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was further extracted with EtOAc (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl solution (2 × 20 mL), dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (hexanes/ethyl acetate, 85/15) to afford 3 (colorless oil, 1.13 g, 4.64 mmol, 60%) and 4 (white solid, 0.151 g, 0.623 mmol, 8%).

Compound 3: [α]D = +191.8° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3054, 2960, 1730, 1474, 652 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.61−6.53 (m, 1H), 6.06−5.98 (m, 1H), 4.57−4.51 (m, 1H), 4.21 (dq, J = 3.2, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.84−2.73 (m, 1H), 2.52 (ddd, J = 16.7, 3.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 0.93 (s, 9H), 0.17 (overlapping singlets, 6H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 196.4, 147.4, 129.9, 70.0, 68.7, 42.4, 25.8, 18.2, −4.43, −4.64.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C12H22O3SiNa = 265.1236, Found Mass = 265.1265 (10 ppm error).

Compound 4: [α]D = +107.0° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3056, 2954, 2860, 1717, 1473, 650.9 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.80−6.67 (m, 1H), 6.04 (ddd, J = 10.3, 1.8, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (ddd, J = 3.7, 3.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (dddd, J = 4.6, 3.6, 3.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (ddd, J = 16.2, 6.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (dd, J = 16.3, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 0.88 (s, 9H), 0.11 (overlapping singlets, 6H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 196.7, 148.0, 130.1, 70.8, 67.8, 44.0, 25.8, 18.1, −4.4, −4.7.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C12H22O3SiNa = 265.1236, Found Mass = 265.1263 (10 ppm error).

2.3. Synthesis of compound 5

An oven-dried 500 mL two-neck round-bottom flask was equipped with a magnetic stir bar and a reflux condenser. The flask was evacuated and backfilled with N2. Mg turnings (4.4 g, 183 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), a few crystals of iodine, and anhydrous THF (124 mL) were added. Next, Cis-1-bromo-1-propene (10.6 mL, 15.1 g, 125 mmol) was slowly added (Caution! There is a significant exotherm during Grignard reagent formation, which may lead to THF reflux). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h.

A 500 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a stir-bar, AlCl3 (5.5 g, 41.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), and anhydrous CH2Cl2 (20 mL). The mixture was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath. Freshly prepared (Z)-prop-1-en-1-ylmagnesium bromide solution (1Min THF, 124 mL, 124 mmol, 3 equiv.) was added over a period of 1 h, and the mixturewas allowed towarm to room temperature over a period of 12 h.

A 500 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a stir-bar, 3 (1 g, 4.13 mmol, 1 equiv.), and anhydrous THF (10 mL). The reaction mixture was cooled to −20 °C using an ice-salt water bath. Freshly prepared tri((Z)-prop-1-en-1-yl)aluminum (0.3 M in THF, 138 mL, 41.3 mmol, 10 equiv.) was slowly added. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature over a period of 12 h. Following this time, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath and quenched with slow addition of 20% aqueous tartaric acid solution (40 mL). After transferring to a separatory funnel, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 100 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel by eluting with hexane/ethyl acetate (80/20) to afford 5 (0.529 g, 1.86 mmol, 45% yield) as a brown oil.

Compound 5: [α]D = +15°(c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3440, 3012, 2958,1717, 1473 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.59−5.49 (m, 1H), 5.45−5.35 (m, 1H), 3.99 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (ddd, J = 11.6, 5.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 2.74−2.57 (m, 2H), 2.57−2.48 (m, 2H), 2.10−2.01 (m, 1H), 1.61 (dd, J = 6.8, 1.8 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (s, 9H), 0.14 (overlapping singlets, 6H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.4, 130.3, 125.6, 73.5, 72.2, 45.5, 41.0, 36.6, 26.2, 18.6, 13.2, −3.7, −4.0.; HRMS (ESI) m z = [M + Na+] calculated for C15H28O3SiNa = 307.1705, Found Mass = 307.1723 (6 ppm error).

2.4. Synthesis of compound 6

A 50 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a magnetic stir bar, 5 (568 mg, 2 mmol, 1 equiv.), and THF (10 mL). The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath. TBAF (1 M in THF, 4 mL, 4 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added, and the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature over a period of 12 h. Following this time, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by column chromatography on Florisil by eluting with hexane/ethyl acetate (30/70 mixture) to afford 6 (brown oil, 0.170 g, 1 mmol, 50%).

Compound 6: [α]D = +3.82° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3440, 3426, 2932, 1714, 1042 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.70−5.46 (m, 2H), 3.99−3.95 (m, 2H), 2.83−2.68 (m, 2H), 2.68−2.50 (m, 2H), 2.43 (s, 1H), 2.34 (s, 1H), 2.10 (ddd, J = 14.2, 4.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 1.63 (dd, J = 6.6, 1.6 Hz, 3H).;13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.8, 129.1, 126.3, 71.6, 71.4, 44.8, 40.6, 35.8, 13.2.; HRMS calculated for C9H14O3SiNa = 193.0841, Found Mass = 193.0837 (2 ppm error).

2.5. Synthesis of compound 7

A 50 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a magnetic stir-bar, 6 (0.64 g, 3.76 mmol, 1.00 equiv.), and anhydrous DMF (10 mL). The reaction flask was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath. Tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI) (69 mg, 0.189 mmol, 0.05 equiv.), TBSCl (626 mg, 4.15 mmol, 1.10 equiv.), NEt3 (0.63 mL, 0.457 g, 4.52 mmol, 1.20 equiv.), and DMAP (105 mg, 0.86 mmol, 0.23 equiv.) were added sequentially. After warming to room temperature over a period of 12 h, the reaction mixture was again cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath and quenched with chilled H2O (20 mL). The reaction mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel and extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 20 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed once with saturated aqueous NaCl solution, and dried with Na2SO4. After the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the resulting residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel by eluting with hexane/ethyl acetate (80/20) to afford 7 (colorless oil, 0.770 g, 2.71 mmol, 72% yield).

Compound 7: [α]D = +9.0° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3423, 2950, 2830, 1710, 1473, 1136, cm−1.;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.71−5.53 (m, 2H), 3.95 (ddd, J = 11.0, 5.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (t, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 2.77−2.56 (m, 3H), 2.49−2.39 (m, 1H), 2.12−2.00 (m, 1H), 1.65−1.57 (m, 3H), 0.90 (s, 9H), 0.09 (overlapping singlets, 6H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.8, 129.5, 125.5, 72.5, 71.9, 45.4, 40.7, 35.5, 25.8, 18.1, 13.1, −4.5, −4.7.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C15H28O3SiNa = 307.1705, Found Mass = 307.1722 = (6 ppm error).

2.6. Synthesis of compound 8

A 50 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a magnetic stir-bar, 7 (0.3 g, 1.05 mmol,1 equiv.) and anhydrous CH2Cl2 (10 mL). The reaction flask was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath. Trimethyl orthoformate (1.15 mL, 1.12 g, 10.5 mmol, 10 equiv.), ethylene glycol (0.6 mL, 0.67 g, 10.7 mmol, 10 equiv.), and p-TsOH·H2O (18 mg, 0.09 mmol, 0.1 equiv.) were added at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature over a period of 2 h. Following this time, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath and quenched with chilled H2O (15 mL). After transferring to a separatory funnel, the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were washed once with saturated aqueous NaCl solution and dried with Na2SO4. After the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the resulting residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel by eluting with hexane/ethyl acetate (85:15) to afford 8 (colorless oil, 0.311 g, 0.95 mmol, 90% yield).

Compound 8: [α]D = −16.5° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3420, 2930, 2840, 1473, 1036, 650.9 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.67−5.42 (m, 2H), 3.95 (p, J = 2.7 Hz, 4H), 3.91−3.85 (m, 1H), 3.65 (t, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (dddd, J = 12.8, 8.5, 4.2, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.97−1.78 (m, 2H), 1.72−1.67 (m, 1H), 1.66−1.62 (m, 3H), 1.38 (ddd, J = 13.0, 4.2, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 0.89 (s, 9H), 0.08 (overlapping singlets, 6H).; = 13C {1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 130.9, 124.5, 108.9, 72.0, 71.4, 64.5, 64.3, 37.7, 34.7, 33.9, 25.9, 18.2, 13.2, −4.5, −4.7·.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C17H32O4SiNa = 351.1968, Found Mass = 351.1984 (5 ppm error).

2.7. Synthesis of compound 9

Compound 9: A 5 mL microwave vial was charged with a stir bar and chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (ClSO2NCO) (0.18 mL, 0.30 g, 2.14 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) and cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath. Formic acid (0.08 mL, 0.098 g, 2.15 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) was slowly added (Caution! Vigorous gas evolution during addition), and the mixture was stirred for 10 min, during which a white solid formed.

Anhydrous acetonitrile (4 mL) was added to this solid. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After 12 h, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C using an ice-water bath, and alcohol 8 (0.28 g, 0.854 mmol, 1 equiv.) dissolved in 0.6 mL of DMA was added dropwise using a syringe. The resulting solution was warmed to room temperature over 5 h. Subsequently, the reaction was quenched with ice water (10 mL) and transferred to a separatory funnel. The organic layer was separated, and then the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl solution (2 × 10 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified through silica gel column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 65:35) to afford 140 mg (0.34 mmol, 40%) of 9 as a white solid.

Compound 9: [α]D = −11.5° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3260, 2857, 1673, 1473, 1036 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.64−5.51 (m, 1H), 5.50−5.39 (m, 1H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 4.74 (s, 1H), 4.05 (ddd, J = 12.1, 5.0, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.02−3.89 (m, 4H), 2.88−2.72 (m, 1H), 2.07−1.95 (m, 1H), 1.85−1.78 (m, 1H), 1.74 (t, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H), 1.69−1.60 (m, 3H), 1.48 (ddd, J = 13.5, 4.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 0.93 (s, 9H), 0.21−0.11 (m, 6H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 128.5, 126.2, 108.1, 85.9, 71.8, 64.7, 64.6, 38.3, 34.9, 34.2, 26.0, 18.7, 13.3, −4.9, −5.1.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C17H33NO6SSiNa = 430.1696, Found Mass = 430.1716 (5 ppm error).

2.8. Synthesis of compound 10

A 20 mL microwave vial containing a magnetic stir-bar was charged with sulfamate 9 (140 mg, 0.343 mmol, 1 equiv.), Pd(OAc)2 (19 mg, 0.085 mmol, 0.25 equiv.), and Cu(OAc)2 (63 mg, 0.347 mmol, 1 equiv.) in 6.8 mL of acetonitrile (final concentration 0.05 M). The reaction vial was sealed and then evacuated and backfilled with oxygen three times. The reaction vessel was then submerged in an oil bath preheated to 55 °C and kept at this temperature under a balloon of O2 (~1 atm) for 36 h. After 36 h, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered through a small plug of silica. The silica plug was further rinsed with CH2Cl2 (20 mL). The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified through silica gel column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 65:35) to afford 83 mg (0.205 mmol, 60%) of 10 as a white solid.

Compound 10: [α]D = +41.0° (c = 1, CHCl3); FT-IR: 3264, 2926, 1180, 654 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.32 (ddd, J = 17.4, 10.7, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.36−5.25 (m, 2H), 4.94 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (dddd, J = 11.7, 7.8, 4.8, 2.0 Hz, 5H), 3.78 (tt, J = 6.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.10−1.90 (m, 3H), 1.82 (dddd, J = 12.9, 4.9, 2.4, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 1.58−1.49 (m, 1H), 0.88 (s, 9H), 0.09 (overlapping singlets, 6H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 135.6, 117.9, 107.9, 81.4, 69.2, 64.8, 64.7, 61.2, 38.4, 33.6, 33.5, 25.8, 18.2, −4.5.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C17H31NO6SSiNa = 428.1539, Found Mass = 428.1500 (9 ppm error).

2.9. Synthesis of compound 11

A 5 mL microwave vial was charged with a magnetic stir bar, 10 (81 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), 2 mL of DMF/H2O (9:1 mixture), PdCl2 (9 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.25 equiv.), and CuCl (40 mg, 0.4 mmol, 2 equiv.). The resulting dark brown suspension was stirred under a balloon of O2 (~1 atm) for 16 h. After 16 h, the reaction was quenched with ice water (10 mL) and transferred to a separatory funnel. The organic layer was separated, and then the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine solution (2 × 10 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified through silica gel column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 60:40) to afford 68 mg (0.16 mmol, 80%) of 11 as a white solid.

Compound 11: [α]D = 20.6° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3185, 2932, 1715, 1438,1073 cm-1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.98 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 4.08−3.86 (m, 5H), 3.57 (dd, J = 6.9, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (ddt, J = 14.0, 4.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (s, 3H), 2.03−1.77 (m, 3H), 1.46−1.36 (m, 1H), 0.87 (s, 9H), 0.09 (s, 3H), 0.08 (s, 3H).; 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 203.8, 107.7, 83.1, 68.8, 66.6, 64.8, 64.7, 38.3, 32.6, 27.5, 27.1, 25.8, 18.2, −4.59, −4.57.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C17H31NO7SSiNa = 444.1488, Found Mass = 444.1455 (7 ppm error).

2.10. Synthesis of compound 14

To a solution of 11 (30 mg, 0.071 mmol, 1 equiv.) in dry DMF (1 mL) was added TMSCHCl2 (0.032 mL, 0.033 g, 0.212 mmol, 3 equiv.) and HCO2Na (1.5 mg, 0.022 mmol, 0.3 equiv.) at room temperature. The resulting solution was heated to 50 °C using an oil bath and stirred at this temperature for 36 h. Following this time, reaction was cooled to room temperature. Subsequently, MeOH (1 mL) and a 1 M aqueous HCl solution (1 mL) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then poured into saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (10 mL). After transferring to a separatory funnel, this mixture was extracted with Et2O (2 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were washed once with brine solution (30 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified through column chromatography on silica gel using hexane/ethyl acetate (80:20) as an eluent to afford 15 mg (0.036 mmol, 50%) of 14 as a white solid.

Compound 14: [α]D = 15.6° (c = 1, CHCl3).; FT-IR: 3185, 2932, 1715, 1438, 1073 cm-1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.06 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 4.92 (s, 1H), 4.65 (dd, J = 9.7, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.05−3.90 (m, 5H), 2.29−2.26 (m, 1H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 1.96 (t, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 1.82 (ddd, J = 4.9, 2.3, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 1.70 (t, J = 13.4 Hz, 1H), 1.07−0.96 (m, 1H), 0.90 (s, 9H), 0.12 (s, 3H), 0.10 (s, 3H).; 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.1, 107.5, 83.7, 68.9, 64.9, 64.8, 64.7, 38.0, 31.5, 28.0, 27.0, 25.8, 18.2, −4.50, −4.53.; HRMS (ESI) m/z = [M + Na+] calculated for C17H31NO7SSiNa = 444.1488, Found Mass = 444.1459 (7 ppm error).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant R35GM142499 awarded to Shyam Sathyamoorthi. Justin Douglas and Sarah Neuenswander (KU NMR Lab) are acknowledged for help with structural elucidation. Lawrence Seib and Anita Saraf (KU Mass Spectrometry Facility) are acknowledged for help acquiring HRMS data. Joel T. Mague thanks Tulane University for support of the Tulane Crystallography Laboratory. Dr. Allen Oliver (University of Notre Dame) is gratefully acknowledged for solving the structure of Compound 12. We thank Chemveda Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd. (Hyderabad, India) for large-scale preparation of Compound 1.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Shyam Sathyamoorthi reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2022.133112.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Privalsky TM, Soohoo AM, Wang J, Walsh CT, Wright GD, Gordon EM, Gray NS, Khosla C, Prospects for antibacterial discovery and development, J. Am. Chem. Soc 143 (2021) 21127–21142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rossolini GM, Arena F, Pecile P, Pollini S, Update on the antibiotic resistance crisis, Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 18 (2014) 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wright PM, Seiple IB, Myers AG, The evolving role of chemical synthesis in antibacterial drug discovery, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 53 (2014) 8840–8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cai L, Yao Y, Yeon SK, Seiple IB, Modular approaches to lankacidin antibiotics, J. Am. Chem. Soc 142 (2020) 15116–15126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moore MJ, Qu S, Tan C, Cai Y, Mogi Y, Jamin Keith D, Boger DL, Next-generation total synthesis of vancomycin, J. Am. Chem. Soc 142 (2020) 16039–16050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mandhapati AR, Yang G, Kato T, Shcherbakov D, Hobbie SN, Vasella A, Böttger EC, Crich D, Structure-based design and synthesis of apramycin–paromomycin analogues: importance of the configuration at the 6′-position and differences between the 6′-amino and hydroxy series, J. Am. Chem. Soc 139 (2017) 14611–14619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feng M, Tang B, Liang HS, Jiang X, Sulfur containing scaffolds in drugs: synthesis and application in medicinal chemistry, Curr. Top. Med. Chem 16 (2016) 1200–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shinde AH, Sathyamoorthi S, Oxidative cyclization of sulfamates onto pendant alkenes, Org. Lett 22 (2020) 896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shinde AH, Nagamalla S, Sathyamoorthi S, N-arylated oxathiazinane heterocycles are convenient synthons for 1,3-amino ethers and 1,3-amino thioethers, Med. Chem. Res 29 (2020) 1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nagamalla S, Johnson DK, Sathyamoorthi S, Sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker approach towards analogs of Bactobolin A, Med. Chem. Res 30 (2021) 1348–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kondo S, Horiuchi Y, Hamada M, Takeuchi T, Umezawa H, A new antitumor antibiotic bactobolin produced by Pseudomonas, J. Antibiot 32 (1979) 1069–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Greenberg EP, Seyedsayamdost MR, Chandler JR, The chemistry and biology of bactobolin: a 10-year collaboration with natural product chemist extraordinaire Jon Clardy, J. Nat. Prod 83 (2020) 738–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Amunts A, Fiedorczuk K, Truong TT, Chandler J, Greenberg EP, Ramakrishnan V, Bactobolin A binds to a site on the 70S ribosome distinct from previously seen antibiotics, J. Mol. Biol 427 (2015) 753–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chandler JR, Truong TT, Silva PM, Seyedsayamdost MR, Carr G, Radey M, Jacobs MA, Sims EH, Clardy J, Greenberg EP, Bactobolin resistance is conferred by mutations in the L2 ribosomal protein, mBio 3 (2012), e00499–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Weinreb SM, Garigipati RS, Design of an efficient strategy for total synthesis of the microbial metabolite (−)-bactobolin, Pure Appl. Chem 61 (1989) 435. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Garigipati RS, Tschaen DM, Weinreb SM, Stereoselective total syntheses of the antitumor antibiotics (+)-actinobolin and (−)-bactobolin from a common bridged lactone intermediate, J. Am. Chem. Soc 112 (1990) 3475–3482. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Garigipati RS, Weinreb SM, Stereoselective total synthesis of the antitumor antibiotic (−)-bactobolin, J. Org. Chem 53 (1988) 4143–4145. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vojáčková P, Michalska L, Nečas M, Shcherbakov D, Böttger EC, Šponer J, Šponer JE, Švenda J, Stereocontrolled synthesis of (−)-Bactobolin A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 142 (2020) 7306–7311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Askin D, Angst C, Danishefsky S, An approach to the synthesis of bactobolin and the total synthesis of N-acetylactinobolamine: some remarkably stable hemiacetals, J. Org. Chem 52 (1987) 622–635. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Underwood R, Fraser-Reid B, Support studies for the conversion of actinobolin into bactobolin, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 (1990) 731–738. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ward DE, Gai Y, Kaller BF, Synthetic studies on actinobolin and bactobolin: synthesis of N-desalanyl-N-[2-(trimethylsilyl)ethanesulfonyl] derivatives from a common intermediate and attempted removal of the SES protecting group, J. Org. Chem 61 (1996) 5498–5505. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Adachi H, Usui T, Nishimura Y, Kondo S, Ishizuka M, Takeuchi T, Synthesis and activities of bactobolin derivatives based on the alteration of the functionality at C-3 position, J. Antibiot 51 (1998) 184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Adachi H, Nishimura Y, Takeuchi T, Synthesis and activities of bactobolin derivatives having new functionality at C-3, J. Antibiot 55 (2002) 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Adachi H, Nishimura Y, Synthesis and biological activity of bactobolin glucosides, Nat. Prod. Res 17 (2003) 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].James MT, Xun-tian J, The wacker reaction and related alkene oxidation reactions, Curr. Org. Chem 7 (2003) 369–396. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rodeschini V, Boiteau J-G, Van de Weghe P, Tarnus C, Eustache J, MetAP-2 inhibitors based on the fumagillin structure. Side-chain modification and ring-substituted analogues, J. Org. Chem 69 (2004) 357–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Carreño MC, Pérez González M, Ribagorda M, Houk KN, Studies of diastereoselectivity in conjugate addition of organoaluminum reagents to (R)-[(p-Tolylsulfinyl)methyl]quinols and derivatives, J. Org. Chem 63 (1998) 3687–3693. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Thomas AA, Nagamalla S, Sathyamoorthi S, Salient features of the aza-Wacker cyclization reaction, Chem. Sci 11 (2020) 8073–8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Weinstein AB, Schuman DP, Tan ZX, Stahl SS, Synthesis of vicinal aminoalcohols by stereoselective aza-wacker cyclizations: access to (−)-Acosamine by redox relay, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 52 (2013) 11867–11870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kister J, Mioskowski C, Trichloromethyltrimethylsilane, sodium formate, and dimethylformamide: a mild, efficient, and general method for the preparation of trimethylsilyl-protected 2,2,2-trichloromethylcarbinols from aldehydes and ketones, J. Org. Chem 72 (2007) 3925–3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Frost JW; Frost KM Biocatalytic synthesis of quinic acid and conversion to hydroquinone U.S. Patent 6,620,602 B2, Sep. 16, 2003.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.