Abstract

Introduction: There are prevalent financial relationships between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry in medical specialties, including otorhinolaryngology. Although these relationships might cause conflicts of interest, no studies have assessed the size and contents of the financial relationships between otorhinolaryngologists and pharmaceutical companies in Japan. This study aims to evaluate the magnitude, prevalence, and trend of the financial relationship between Japanese otolaryngologists and pharmaceutical companies.

Methods: Using payment data publicly disclosed by 92 pharmaceutical companies, we examined the size, prevalence, and trend in personal payments made to the otorhinolaryngologist board certified by the Japanese Society of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (JSO-HNS) between 2016 and 2019 in Japan. Furthermore, differences in payments were evaluated by whether otolaryngologists were clinical practice guideline authors, society board members, and academic journal editors or not. Trends in payments were evaluated by generalized estimating equations.

Results: Of 8,190 otorhinolaryngologists, 3,667 (44.8%) were paid a total of $13,873,562, in payments for lecturing, consulting, and writing by 72 pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. The median four-year combined payment per physician was $1,022 (interquartile range: $473-$2,526). Top 1%, 5%, and 10% of otorhinolaryngologists received 42.3% (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 37.2%-47.4%), 69.3% (95% CI: 65.9%-72.8%), and 80.6% (95% CI: 78.3%-82.9%) of overall payments, respectively. The median payments per physician were significantly higher among otorhinolaryngologists authoring clinical practice guidelines ($11,522), society board members ($22,261), and journal editors ($35,143) than those without. The payments and number of otorhinolaryngologists receiving payments remained stable between 2016 and 2019.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that a minority but a large number of otorhinolaryngologists received personal payments from pharmaceutical companies for the reimbursement of lecturing, consulting, and writing in Japan. Large amounts of these personal payments were significantly concentrated on a small number of leading otorhinolaryngologists.

Keywords: medical ethics, public health policy, health policy and economics, financial conflicts of interest, ethics, ethics and professionalism, otolaryngologist, industry payment, japan, conflict of interest

Introduction

Although collaborations between industry and healthcare professionals can bring breakthroughs in medicine, several medical scandals and limited transparency in the financial relationships between healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical companies led to concern for the undue influence of financial relationships on patient care. Since 2013, the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA), the largest pharmaceutical trade organization in Japan, has required all pharmaceutical companies belonging to the JPMA, whose share account for more than 80% of total sales for pharmaceutical products in Japan [1], to disclose their payments made to healthcare professionals for lecturing, consulting, and writing, based on the JPMA voluntary transparency guidance [2,3]. This voluntary payment disclosure by pharmaceutical companies has enabled the evaluation of the detailed magnitude of the financial relationships between healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical companies in several specialties [4-12].

As shown in previous studies in the United States, there are large and prevalent financial transfers from pharmaceutical industries to otorhinolaryngologists for various purposes [13-17], as well as other specialty physicians [18-25]. The payments from pharmaceutical companies often disproportionately concentrate on small numbers of physicians in leading and authoritative positions who are required to be independent and unbiased from any industries [4,26-30], namely, key opinion leaders [31,32]. This trend would exist among Japanese otorhinolaryngologists, considering previous studies showing that there were substantial and prevalent financial relationships between leading physicians and pharmaceutical companies in other specialties in Japan [7,9,33-35]. However, there was a lack of assessment regarding the whole picture of the financial relationships between pharmaceutical companies and otorhinolaryngologists in Japan. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the magnitude, prevalence, and trend in personal payments made to otorhinolaryngologists by pharmaceutical companies for the latest years in Japan.

Materials and methods

Study design and study participants

This retrospective study examined the magnitude and trends in financial relationships between pharmaceutical companies and all otorhinolaryngologists board-certified by the Japanese Society of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (JSO-HNS). As the JSO-HNS did not disclose the name list of board-certified otorhinolaryngologists for the previous years, we considered all board-certified otorhinolaryngologists in 2021. The JSO-HNS, established in 1893, is the sole and most authoritative professional medical society certifying otorhinolaryngologists in the field of otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery in Japan. The JSO-HNS has contributed to training otorhinolaryngologists, funded clinical trials and basic research, published many clinical practice guidelines for otorhinolaryngological diseases, and issued the English-language academic journal (Auris Nasus Larynx). This study defined leading otorhinolaryngologists as board-certified otorhinolaryngologists authoring clinical practice guidelines, board members of the JSO-HNS, and editorial members of Auris Nasus Larynx.

Data collection

As the JSO-HNS did not disclose the name list of board-certified otorhinolaryngologists for the previous years, the name, practicing region, and prefecture of all board-certified otorhinolaryngologists in 2021 were extracted from the official webpage of the JSO-HNS. Furthermore, we collected the name of all clinical practice guideline authors issued and reviewed by the JSO-HNS between 2015 and 2020 (including one year before and after the payment period), the JSO-HNS board members in 2018-2019 and 2020-2021, and editorial members of Auris Nasus Larynx in April 2022. For the data collection of society board members, we previously collected the name list of the JSO-HNS in 2018-2019 and 2020-2021 [29]. As the Auris Nasus Larynx did not publicly provide the name list of editorial board members in previous years, we collected the latest editorial members of Auris Nasus Larynx in April 2022.

The payments concerning lecturing, consulting, and writing paid to the board-certified otorhinolaryngologists were extracted from a total of 92 pharmaceutical companies belonging to the JPMA between 2016 and 2019. The period of payment data collection was determined by our availability of data collection. The companies have published and updated the payment data each year on their company websites. The payment data for all companies belonging to the JPMA were collected from 2016 and May 2022, and the payment data from 2019 are the latest analyzable data in Japan. Payment categories were described in our previous study and the JPMA transparency guideline [3,35]. The detailed procedure of the payment collection was noted previously [4].

Analysis

First, the payment data were descriptively analyzed. Payments per physician were also calculated only for physicians receiving payments each year, as in other previous studies [9,16,18,36-38]. Second, the payment concentration was evaluated by the shares of the payment values held by the top 1%, 5%, 10%, and 25% of the otorhinolaryngologists and the Gini coefficient at the physician level. The Gini index ranges from 0 to 1, and the greater the Gini index, the greater the disparity in the distribution of payments [10,34,39-41]. Third, we calculated descriptive statistics and evaluated payment differences among the leading otorhinolaryngologists, including guideline authors, society board members, journal editors, and other otorhinolaryngologists. The differences in payments by each variable were evaluated by chi-square and Fisher's exact tests for the proportion of otorhinolaryngologists receiving payments and by Mann-Whitney U test for payment values per otorhinolaryngologist.

Furthermore, the linear log-linked Poisson regression model was used to assess the association between the relative risk of payment receipt and the otorhinolaryngologist characteristics. To account for the highly skewed distribution of payment values, a negative binomial regression model was employed to evaluate the association between the relative monetary value of payments per physician and the otorhinolaryngologist characteristics, including practicing prefecture, participation in clinical guideline development, JSO-HNS board membership, and editorial membership of the society journal, as in previous studies [9,35,37,38]. Finally, we evaluated the trends in payments per physician and the number of physicians receiving payments between 2016 and 2019 by the population-averaged generalized estimating equation (GEE) with the panel data of the annual payments. As the payment distribution was highly skewed, the negative binomial GEE model for the payment values per physician and linear log-linked GEE model with Poisson distribution for the number of otorhinolaryngologists with payments were selected [10,12,42]. The payment values were converted from Japanese yen (¥) to US dollars ($) using the 2019 average monthly exchange rates of ¥109.0 per $1. All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel, version 16.0 (Microsoft Corporation, United States) and Stata statistical software, version 15 (StataCorp, 2017, College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.).

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of the Medical Governance Research Institute approved this study (approval number: MG2018-04-20200605; approval date: June 5, 2020). As this retrospective analysis only included publicly available information, informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Patient and public involvement

No patient was involved in this study.

Results

Overall and per-otorhinolaryngologist payments

At the time of this study, we identified 8,190 otorhinolaryngologists board-certified by the JSO-HNS. Of the 8,190 otorhinolaryngologists, 3,667 (44.8%) were paid a total of $13,873,562, entailing 22,076 contracts in payments for lecturing, consulting, and writing by 72 pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019 (Table 1). The median payment per physician was $0 (interquartile range (IQR): $0-$851) for overall otorhinolaryngologists. For otorhinolaryngologists receiving payments, the median payment per physician was $1,022 (IQR: $473-$2,526), while the average payment was $3,783 (standard deviation (SD): $14,349). The median payment contracts and number of companies making payments per physician were 3.0 (IQR: 1.0-6.0) and 2.0 (IQR: 1.0-4.0) over the four years, respectively. One otorhinolaryngologist received a maximum payment of $490,081 and 332 payment contracts.

Table 1. Summary of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies to board-certified otorhinolaryngologists between 2016 and 2019.

SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range

| Variables | |

| Total | |

| Payment values, $ | 13,873,562 |

| Instances, No. | 22,076 |

| Companies, No. | 72 |

| Average per physician (SD) | |

| Payment values, $ | 3,783 (14,349) |

| Instances, No. | 6.0 (13.6) |

| Companies, No. | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Median per physician (IQR) | |

| Payment values, $ | 1,022 (473‒2,526) |

| Instances, No. | 3.0 (1.0‒6.0) |

| Companies, No. | 2.0 (1.0‒4.0) |

| Range | |

| Payment values, $ | 28‒490,081 |

| Instances, No. | 1.0‒332 |

| Companies, No. | 1.0‒27.0 |

| Category of payments | |

| Lecturing | |

| Payment value, $ (%) | 11,968,045 (84.8) |

| Instances, No. (%) | 18,714 (84.8) |

| Physicians, No. (%) | 3373 (41.2) |

| Consulting | |

| Payment value, $ (%) | 1,075,487 (7.8) |

| Instances, No. (%) | 2,121 (9.6) |

| Physicians, No. (%) | 1112 (13.6) |

| Writing | |

| Payment value, $ (%) | 701,495 (5.1) |

| Instances, No. (%) | 1,075 (4.9) |

| Physicians, No. (%) | 494 (6.0) |

| Other | |

| Payment value, $ (%) | 128,534 (0.9) |

| Instances, No. (%) | 168 (0.8) |

| Physicians, No. (%) | 113 (1.4) |

Payments by category and payment concentration

Payments for lecturing occupied 86.3% of overall monetary values ($11,968,045) and 84.8% of overall payment contracts (18,714 contracts) between 2016 and 2019. Of 8,190 eligible otorhinolaryngologists, 3,373 (41.2%), 1,112 (13.6%), and 494 (6.0%) received one or more compensation payments for lecturing, consulting, and writing from the pharmaceutical companies over the four years, respectively.

While majority of otorhinolaryngologists did not receive any payments from the pharmaceutical companies over the four years, top 1%, 5%, 10%, and 25% of otorhinolaryngologists received 42.3% (95% CI: 37.2%-47.4%), 69.3% (95% CI: 65.9%-72.8%), 80.6% (95% CI: 78.3%-82.9%), and 94.8% (95% CI: 94.1%-95.5%) of overall payments, respectively. The Gini coefficient for the four-year combined payments per physician was 0.889, indicating that the payments disproportionately concentrated on small numbers of otorhinolaryngologists.

Payments to leading otorhinolaryngologists: clinical practice guideline authors, society board members, and academic journal editors

We identified a total of 139 individual authors from eight clinical practice guidelines accredited or authorized by the JHO-HNS between 2015 and 2020 (Table 2). Of the 139 authors, 101 (72.7%) authors were board-certified otorhinolaryngologists, and 94 (93.1%) received one or more personal payments for lecturing, consulting, and writing compensations. A total of $2,435,239 (17.6% ($2,435,239 out of $13,873,562) of the overall personal payments from the companies) were made to 94 otorhinolaryngologists authoring clinical practice guidelines. The aggregated payment per physician was significantly higher among otorhinolaryngologists authoring clinical practice guidelines than that of otorhinolaryngologists not involved in authoring guidelines ($11,522 (IQR: $3,090-$32,390) vs. $0 (IQR: $0-$817), p<0.001).

Table 2. Payments to the board-certified otorhinolaryngologists with leading roles between 2016 and 2019.

a. The difference in proportion of otorhinolaryngologists with payments was evaluated by the chi-square test and fisher exact test.

b. The difference in payments per otorhinolaryngologist was evaluated by the Mann-Whitney U test for the two groups.

c. The interaction between continuous variable society board membership and journal editorial membership were included in multivariable regression models. The relative risk for the interaction was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.63–1.03) and relative monetary value for the interaction was 2.29 (95% CI: 0.63–8.38).

SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

| Physician with payments | Payment per physician $ | Relative payments | |||||||

| Number (%) | P valuea | Average (SD) | Median (IQR) | P valueb | Relative risk for receiving payments (95% CI) | P value | Relative monetary value (95% CI) | P value | |

| Clinical practice guideline | |||||||||

| Non-guideline author otorhinolaryngologists | 3,573 (44.2) | <0.001 | 1,414 (8,751) | 0 (0-817) | <0.001 | Ref. | <0.001 | Ref. | <0.001 |

| Otorhinolaryngologists authoring guideline | 94 (93.1) | 24,111 (33,621) | 11,522 (3,090-32,390) | 1.96 (1.82-2.12) | 13.03 (9.55-17.79) | ||||

| Board membershipc | |||||||||

| Non-board members | 3633 (44.6) | <0.001 | 1,550 (9,109) | 0 (0-831) | <0.001 | Ref. | <0.001 | Ref. | <0.001 |

| Board membership | 34 (94.4) | 34,298 (44,388) | 22,261 (4,537-50,331) | 1.47 (1.20-1.79) | 8.57 (3.04-24.17) | ||||

| Journal editorial membershipc | |||||||||

| Non-editor otorhinolaryngologists | 3,648 (44.7) | <0.001 | 1,603 (9,365) | 0 (0-851) | <0.001 | Ref. | <0.001 | Ref. | 0.001 |

| Editor otorhinolaryngologists | 19 (100) | 40,746 (46,059) | 35,143 (7,733-50,373) | 1.21 (1.11-1.33) | 0.54 (0.38-0.77) | ||||

All 36 board members of the JSO-HNS during the 2018-2019 and 2020-2021 periods were board-certified otorhinolaryngologists. Of the 36 board-certified otorhinolaryngologists with the JSO-HNS board membership, 34 (94.4%) received a total of $1,234,715 (8.9% of overall payments) and a median payment of $22,261 (IQR: $4,537-$50,331) per physician (Table 2). Both the proportion of otorhinolaryngologists receiving payments (94.4% vs. 44.6%, p<0.001) and the payments per physician ($22,261 (IQR: $4,537-$50,331) vs. $0 (IQR: $0-$831), p<0.001) were significantly higher for the otorhinolaryngologists positioned as the JSO-HNS board member than those without board membership.

There were 20 Japanese editors of Auris Nasus Larynx, and among them, 19 editors were board-certified otorhinolaryngologists. All 19 (100%) board-certified otorhinolaryngologists who are editors of Auris Nasus Larynx received payments of $774,171 (5.6% of the overall payments) in total and $35,143 (IQR: $7,733-$50,373) in median per-physician payments from pharmaceutical companies (Table 2).

The multivariable Poisson regression model showed that clinical practice guideline authorship, JSO-HNS board membership, and editorial membership in the academic journal were significantly associated with 1.96 (95% CI: 1.82-2.12) times, 1.47 (95% CI: 1.10-1.79) times, and 1.21 (95% CI: 1.11-1.33) times higher likelihood to accept personal payments from pharmaceutical companies than those without authorships or memberships (Table 2). The multivariable negative binomial regression model indicated that clinical practice guideline authorship and JSO-HNS board membership were positively associated 13.04 (95% CI: 9.55-17.79) times and 8.57 (95% CI: 3.04-24.17) times higher monetary values in personal payments, while editorial membership in the academic journal was negatively associated with payment values.

The JSO-HNS required clinical practice guideline authors to declare their financial conflicts of interest (FCOIs) with the industry, and the authors disclosed their FCOIs in the guidelines. Meanwhile, there was no FCOI disclosure among the JSO-HNS board members and the academic journal editors.

Trends in personal payments between 2016 and 2019

The total annual payments from the pharmaceutical companies ranged from $3,356,647 in 2016 to $3,615,634 in 2017. A total of 1,988 (24.3%) otorhinolaryngologists in 2019 to 2,129 (26.0%) otorhinolaryngologists in 2018 received more than one personal payment from the companies in a single year (Table 3). The median annual payments per physician was $511 (IQR: $307‒$1,188) in 2016 to $619 (IQR: $473‒$1,328) in 2019, while the average annual payment per physician was $1,663 (SD: $5,505) to $1,761 (SD: $5,518). There were no significant annual changes in the total payments, payments per physician, and the number of otorhinolaryngologists receiving payments. A sensitivity analysis, limiting payments from 63 companies whose payment data were available throughout the four years, also confirmed that there were no significant annual changes in total payments, payment per physician, and the number of otorhinolaryngologists with payments between 2016 and 2019.

Table 3. Trend of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies to board-certified otorhinolaryngologists between 2016 and 2019.

a. There were nine companies without payment data through the four years and were excluded from the trend analysis.

SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range

| Variables | Payment year | Average yearly change (95%CI), % | P value | |||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||

| All pharmaceutical companies | ||||||

| Total payments, $ | 3,356,647 | 3,615,634 | 3,463,336 | 3,437,945 | -0.26 (-2.06‒2.59) | 0.84 |

| Average payments per physician (SD), $ | 1,663 (5,505) | 1,761 (5,518) | 1,627 (4,319) | 1,729 (4,249) | 0.27 (-2.72‒3.35) | 0.86 |

| Median payments per physician (IQR), $ | 511 (307‒1,188) | 511 (307‒1,209) | 613 (411‒1,211) | 619 (473‒1,328) | ||

| Range of payments per physician, $ | 28‒164,556 | 94‒151,906 | 92‒91,580 | 92‒82,038 | ||

| Physicians with payments, n (%) | 2,019 | 2,053 | 2,129 | 1,988 | -0.083 (-1.34‒1.19) | 0.90 |

| Gini index | 0.923 | 0.922 | 0.910 | 0.913 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Pharmaceutical companies with 4-years payment dataa | ||||||

| Total payments , $ | 3,315,057 | 3,608,993 | 3,417,689 | 3,358,464 | -0.18 (-3.06‒2.70) | 0.90 |

| Average payments per physician (SD), $ | 1,653 (5,491) | 1,758 (5,509) | 1,616 (4,290) | 1,714 (4,219) | -0.18 (-3.14‒2.87) | 0.91 |

| Median payments per physician (IQR), $ | 511 (307‒1,188) | 511 (307‒1,209) | 613 (409‒1,211) | 613 (473‒1,306) | ||

| Range of payments per physician, $ | 28‒163,610 | 94‒151,906 | 92‒90,161 | 92‒82,038 | ||

| Physicians with payments, n (%) | 2,005 | 2,053 | 2,115 | 1,959 | -0.37 (-1.63‒0.90) | 0.56 |

| Gini index | 0.923 | 0.922 | 0.911 | 0.914 | ‒ | ‒ |

Payments by company

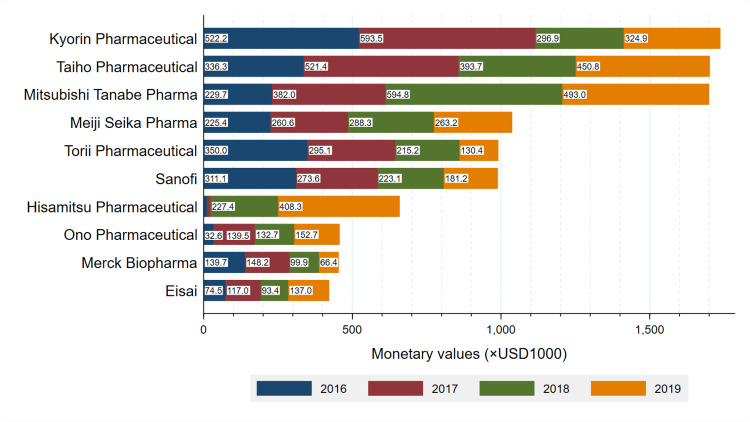

Total payments by company are described in Figure 1. Kyorin Pharmaceutical paid the largest personal payments to the board-certified otorhinolaryngologists, accounting for 12.6% ($1,745,682 out of $13,873,561) of overall payments. Similarly, payments from Taiho Pharmaceutical and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, the second and third largest paying companies, accounted for 12.3% ($1,705,181) and 12.3% ($1,704,126) of overall payments, respectively. The payments from the top 10 companies occupied 73.3% of overall personal payments between 2016 and 2019. Most companies made personal payments for the purpose of lecturing to the board-certified otorhinolaryngologists.

Figure 1. Payment trends by company.

Total payments made to all board-certified otorhinolaryngologists for lecturing, consulting, and writing between 2016 and 2019 by each company.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a minority but a large number of otorhinolaryngologists received personal payments from pharmaceutical companies for the reimbursement of lecturing, consulting, and writing in Japan. Large amounts of these personal payments were significantly concentrated on a small number of otorhinolaryngologists with leading positions, such as clinical practice guideline authors, society board members, and academic journal editors in the field of otorhinolaryngology. We observed that the personal financial relationships between the otorhinolaryngologists and pharmaceutical companies had remained stable over the four years in Japan. Our findings show significant similarities and differences compared to previous studies assessing this issue in Japan and other developed countries.

First, this large sample-sized longitudinal observational study elucidated that 44.8% of all board-certified otorhinolaryngologists received a median personal payment of $1,022 from pharmaceutical companies. Previous studies in Japan reported that there was an increasing trend in physicians receiving payments from pharmaceutical companies in terms of the number of physicians with payments and payments per physician [5,10,35,42,43]. The proportion of physicians with payments and median four-year personal payments was from 62.0% in pulmonology [12] to 70.6% in medical oncology [5] and $2,210 in pulmonology [12] to $3,183 in infectious diseases [43], respectively. Smaller payments made to otorhinolaryngologists as observed in this study were consistent with many previous studies in the United States [13-15,18,44]. Pathak et al. found that US otorhinolaryngologists received the second lowest personal payments in surgical specialties between 2014 and 2015 [15]. Cvetanovich et al. [44] and Rathi et al. [13] reported that the trend of lowest payments made to the otorhinolaryngologists persisted since the launch of the Open Payments Program in 2013. Fewer expensive and novel drugs and the large number of otorhinolaryngologists could contribute to the lower payment values both in Japan and the US.

Second, the personal financial relationships between the otorhinolaryngologists and pharmaceutical companies remained stable over the four years at both low monetary payment values and number of otorhinolaryngologists with payments. In contrast to our findings, Morse et al. previously observed that there was an increasing trend in personal payments among the US otorhinolaryngologists between 2014 and 2016 [14], while the increasing trend was not observed in 2017 [16]. Meanwhile, even lower personal payments to otorhinolaryngologists significantly influence otorhinolaryngologists’ clinical practice, such as increasing brand-name prescriptions [45], prescribing more brand-name intranasal corticosteroids over generic alternatives [46], and performing more controversial treatment, such as sinus balloon catheter dilation [47,48]. Accumulating evidence strongly suggests that personal payments made by pharmaceutical companies significantly distort physicians’ prescribing patterns, which were potentially harmful to patients [45,47,49-56], increase healthcare costs [49,56-59], and lower patients’ trust in physicians [60-62], while many physicians have denied the influence and justified their personal financial relationships with industries [63-65].

In addition, our study directly demonstrated that large amounts of personal payments significantly concentrated on only a small number of otorhinolaryngologists positioned in authoritative and public roles, such as clinical practice guideline authors, society board members, and academic journal editors. A high concentration of payments on leading physicians, namely, key opinion leaders, is pervading in medicine worldwide [7,9,26-28,30,32,37,66-69]. Moynihan et al. elucidated that 72% of board members of 10 US professional medical societies in the highest financial burden disease areas accepted a median of $6,026 in personal payments from pharmaceutical and medical device companies between 2013 and 2018 [27]. Similarly, Saito et al. reported that 86.9% of the board members from 19 major Japanese professional medical societies received a median per-physician payment of $7,486 in 2016 [29]. Moreover, there are prevalent and large FCOIs among clinical practice guideline authors and journal editors in many developed countries [70-77]. Furthermore, many of the financial relationships between leading physicians and pharmaceutical companies are undisclosed to the public and underreported [4,11,27,33,34,43,75,78-84], as we found that the JSO-HNS did not disclose FCOIs among the board members and academic journal editors. Unlike leading physicians conducting clinical trials and research sponsored by the industry, leading physicians, such as clinical practice guideline authors, society board members, and academic journal editors, are necessary to manage and, if possible, be free from financial interest with the industry, as their financial interest with industry conflict with their primary interest [6,7,9-11,33,41,42,81,82,85-88]. Currently, FCOIs among clinical practice guideline authors are strictly managed by many guideline-developing organizations: the minority of guideline authors with FCOIs involve in guideline development, all FCOIs for the past three years are declared and disclosed by guideline authors, and the guideline chairperson is required to be free from any FCOIs with industry [11,81,84,86,88-90]. Several academic journals, such as the Annals of Emergency Medicine, the official journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians, and the Journal of Urology, the official journal of the American Urological Association, disclose the editors’ FCOIs on journal webpages [75]. Transparency and rigorous management are necessary for financial relationships between pharmaceutical companies and leading otorhinolaryngologists with authoritative and public positions.

Limitations

This study included several limitations: First, there would be underestimated payments made by non-member companies of the JPMA to the otorhinolaryngologists. However, as the member companies accounted for 80.8% of the total pharmaceutical sales in Japan in 2018 [1], such an underestimation of payments could be minimized by including data from all member companies. Second, the pharmaceutical companies were not required to disclose other categories of payments, such as meals, beverages, travel, and stock ownership, at an individual level, according to the JPMA guidance [3]. This could have led to underestimations of the extent and prevalence of overall financial relationships between otorhinolaryngologists and industries. Third, this study included otorhinolaryngologists as of November 2021, as the JSO-HNS did not disclose the name list of otorhinolaryngologists for previous years. Therefore, this study would have included otorhinolaryngologists who were not certified during the study period. Fourth, the payment magnitude and trend may not be applicable to other countries.

Conclusions

Although a minority of otorhinolaryngologists board-certified by the JSO-HNS stably received personal payments from pharmaceutical companies for the reimbursement of lecturing, consulting, and writing between 2016 and 2019, large amounts of payments significantly concentrated on a relatively small number of otorhinolaryngologists. Leading otorhinolaryngologists, such as clinical practice guideline authors, society board members, and academic journal editors, significantly accepted far larger personal payments than those who were not.

The authors have declared financial relationships, which are detailed in the next section.

Akihiko Ozaki declare(s) personal fees from Medical Network Systems (MNES). Ozaki received personal fees from Medical Network Systems (MNES) outside the scope of the submitted work.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Ethics Committee of the Medical Governance Research Institute issued approval MG2018-04-20200605

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Data book 2023. [ Aug; 2023 ]. 2023. https://www.jpma.or.jp/news_room/issue/databook/en/rfcmr00000000an3-att/DATABOOK2023_en.pdf https://www.jpma.or.jp/news_room/issue/databook/en/rfcmr00000000an3-att/DATABOOK2023_en.pdf

- 2.Overview and transparency of non-research payments to healthcare organizations and healthcare professionals from pharmaceutical companies in Japan: analysis of payment data in 2016. Ozaki A, Saito H, Senoo Y, et al. Health Policy. 2020;124:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regarding the transparency guideline for the relation between corporate activities and medical institutions [Article in Japanese] [ Mar; 2022 ]. 2018. https://www.jpma.or.jp/english/code/transparency_guideline/eki4g60000003klk-att/transparency_gl_intro_2018.pdf. https://www.jpma.or.jp/english/code/transparency_guideline/eki4g60000003klk-att/transparency_gl_intro_2018.pdf.

- 4.Pharmaceutical company payments to dermatology clinical practice guideline authors in Japan. Murayama A, Ozaki A, Saito H, et al. PLoS One. 2020;15:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pharmaceutical payments to certified oncology specialists in Japan in 2016: a retrospective observational cross-sectional analysis. Ozaki A, Saito H, Onoue Y, et al. BMJ Open. 2019;9:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Financial relationships between pharmaceutical companies and rheumatologists in japan between 2016 and 2019. Murayama A, Mamada H, Shigeta H, et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2023;29:118–125. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Financial conflicts of interest between pharmaceutical companies and executive board members of internal medicine subspecialty societies in Japan between 2016 and 2020. Murayama A, Saito H, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. J Eval Clin Pract. 2023 doi: 10.1111/jep.13877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Characteristics and distribution of scholarship donations from pharmaceutical companies to Japanese healthcare institutions in 2017: a cross sectional analysis. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Saito H, et al. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2023 doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2023.7621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pharmaceutical payments to Japanese board-certified dermatologists: a 4-year retrospective analysis of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Saito H, Ozaki A. Sci Rep. 2023;13:7425. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-34705-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross-sectional analysis of pharmaceutical payments to Japanese board-certified gastroenterologists between 2016 and 2019. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Kawashima M, Saito H, Yamashita E, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. BMJ Open. 2023;13:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Undisclosed financial conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies among the authors of the Esophageal Cancer Practice Guidelines 2017 by the Japan Esophageal Society. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Shigeta H, Saito H, Yamashita E, Tanimoto T, Akihiko O. Dis Esophagus. 2022;35 doi: 10.1093/dote/doac056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nature and trends in personal payments made to the respiratory physicians by pharmaceutical companies in Japan between 2016 and 2019. Murayama A, Hoshi M, Saito H, et al. Respiration. 2022;101:1088–1098. doi: 10.1159/000526576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the physician payment sunshine act. Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:993–999. doi: 10.1177/0194599815573718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Increasing industry involvement in otolaryngology: insights from 3 years of the Open Payments database. Morse E, Fujiwara RJ, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159:501–507. doi: 10.1177/0194599818778502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assessment of nonresearch industry payments to otolaryngologists in 2014 and 2015. Pathak N, Fujiwara RJ, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158:1028–1034. doi: 10.1177/0194599818758661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Industry involvement in otolaryngology: updates from the 2017 Open Payments database. Morse E, Berson E, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:265–270. doi: 10.1177/0194599819838268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Industry payments for otolaryngology research: a four-year analysis of the Open Payments database. Brauer PR, Morse E, Mehra S. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:314–320. doi: 10.1002/lary.27896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Types and distribution of payments from industry to physicians in 2015. Tringale KR, Marshall D, Mackey TK, Connor M, Murphy JD, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. JAMA. 2017;317:1774–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the Open Payments program. Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Industry payments to obstetrician-gynecologists: an analysis of 2014 Open Payments data. Tierney NM, Saenz C, McHale M, Ward K, Plaxe S. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:376–382. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Financial relationships between urologists and industry: an analysis of Open Payments data. Maruf M, Sidana A, Fleischman W, Brancato SJ, Purnell S, Agrawal S, Agarwal PK. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urpr.2017.03.012. Urol Pract. 2018;5:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Analysis of payments to GI physicians in the United States: Open Payments data study. Gangireddy VG, Amin R, Yu K, Kanneganti P, Talla S, Annapureddy A. JGH Open. 2020;4:1031–1036. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Industry payment trends to orthopaedic surgeons from 2014 to 2018: an analysis of the first 5 years of the Open Payments database. Heckmann ND, Mayfield CK, Chung BC, Christ AB, Lieberman JR. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:0–8. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Industry payments to nephrologists in the United States. Pakanati AR, Kovvuru K, Thombre V, Kanduri SR, Nalleballe K, Ranabothu S. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Industry payments to practicing US rheumatologists, 2014-2019. Putman MS, Goldsher JE, Crowson CS, Duarte-García A. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41896. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:2138–2144. doi: 10.1002/art.41896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunshine on KOLs: assessment of the nature, extent and evolution of financial ties between the leaders of professional medical associations and the pharmaceutical industry in France from 2014 to 2019: a retrospective study. Clinckemaillie M, Scanff A, Naudet F, Barbaroux A. BMJ Open. 2022;12:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Financial ties between leaders of influential US professional medical associations and industry: cross sectional study. Moynihan R, Albarqouni L, Nangla C, Dunn AG, Lexchin J, Bero L. BMJ. 2020;369:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pharmaceutical industry payments to leaders of professional medical associations in Australia: focus on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Karanges EA, Ting N, Parker L, Fabbri A, Bero L. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49:151–154. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-08-19-5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pharmaceutical company payments to executive board members of professional medical associations in Japan. Saito H, Ozaki A, Kobayashi Y, Sawano T, Tanimoto T. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:578–580. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assessment of pharmaceutical company and device manufacturer payments to gastroenterologists and their participation in clinical practice guideline panels. Nusrat S, Syed T, Nusrat S, Chen S, Chen WJ, Bielefeldt K. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:0. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Key opinion leaders and the corruption of medical knowledge: what the Sunshine Act will and won't cast light on. Sismondo S. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41:635–643. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Key opinion leaders: independent experts or drug representatives in disguise? Moynihan R. BMJ. 2008;336:1402–1403. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39575.675787.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evaluation of financial and nonfinancial conflicts of interest and quality of evidence underlying psoriatic arthritis clinical practice guidelines: analysis of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies and authors' self-citation rate in Japan and the United States. Mamada H, Murayama A, Kamamoto S, et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023;75:1278–1286. doi: 10.1002/acr.25032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evaluation of financial conflicts of interest and quality of evidence in Japanese gastroenterology clinical practice guidelines. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Murata N, et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:565–573. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pharmaceutical payments to Japanese certified hematologists: a retrospective analysis of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Kusumi E, Murayama A, Kamamoto S, et al. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:54. doi: 10.1038/s41408-022-00656-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the Open Payment data. Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1307–1313. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A nine-year investigation of healthcare industry payments to pulmonologists in the United States. Murayama A, Kugo H, Saito Y, Saito H, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202209-827OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Industry payments during the COVID-19 pandemic to cardiologists in the United States. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Shigeta H, Ozaki A. CJC Open. 2023;5:253–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Industry payments to cardiologists. Annapureddy A, Murugiah K, Minges KE, Chui PW, Desai N, Curtis JP. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:0. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Analysis of pharmaceutical industry payments to UK health care organizations in 2015. Ozieranski P, Csanadi M, Rickard E, Tchilingirian J, Mulinari S. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:0. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pharmaceutical payments to Japanese Board-Certified Head and Neck Surgeons between 2016 and 2019. Murayama A, Shigeta H, Kamamoto S, et al. https://doi.org/10.1002/oto2.31. OTO Open. 2023;7:0. doi: 10.1002/oto2.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evaluation of financial relationships between Japanese certified pediatric hematologist/oncologists and pharmaceutical companies: a cross-sectional analysis of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Kamamoto S, Murayama A, Kusumi E, et al. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69:0. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pharmaceutical payments to Japanese board-certified infectious disease specialists: a four-year retrospective analysis of payments from 92 pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Saito H, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Industry financial relationships in orthopaedic surgery: analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments database and comparison with other surgical subspecialties. Cvetanovich GL, Chalmers PN, Bach BR Jr. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1288–1295. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The association between industry payments and brand-name prescriptions in otolaryngologists. Morse E, Hanna J, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:605–612. doi: 10.1177/0194599819852321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The association of industry payments to physicians with prescription of brand-name intranasal corticosteroids. Morse E, Fujiwara RJ, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159:442–448. doi: 10.1177/0194599818774739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The role of industry influence in sinus balloon dilation: trends over time. Gadkaree SK, Rathi VK, Gottschalk E, Feng AL, Phillips KM, Scangas GA, Metson R. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:1540–1545. doi: 10.1002/lary.27203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cross-sectional analysis of the relationship between paranasal sinus balloon catheter dilations and industry payments among otolaryngologists. Fujiwara RJ, Shih AF, Mehra S. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157:880–886. doi: 10.1177/0194599817728897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Association between payments by pharmaceutical manufacturers and prescribing behavior in rheumatology. Duarte-García A, Crowson CS, McCoy RG, et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Are financial payments from the pharmaceutical industry associated with physician prescribing? : a systematic review. Mitchell AP, Trivedi NU, Gennarelli RL, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:353–361. doi: 10.7326/M20-5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Association between industry marketing payments and prescriptions for PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/Kexin type 9) inhibitors in the United States. Inoue K, Figueroa JF, DeJong C, Tsugawa Y, Orav EJ, Shen C, Kazi DS. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:0. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Association of biologic prescribing for inflammatory bowel disease with industry payments to physicians. Khan R, Nugent CM, Scaffidi MA, Gimpaya N, Grover SC. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1424–1425. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Industry payments to physician specialists who prescribe repository corticotropin. Hartung DM, Johnston K, Cohen DM, Nguyen T, Deodhar A, Bourdette DN. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:0. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Industry relationships are associated with performing a greater number of sinus balloon dilation procedures. Eloy JA, Svider PF, Bobian M, Harvey RJ, Gray ST, Baredes S, Folbe AJ. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.21976. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7:878–883. doi: 10.1002/alr.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng CW, Lin GA, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1114–1122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Industry-sponsored meals are associated with increased prescriptions and Medicare expenditures on brand-name colchicine in the United States [PREPRINT] Murayama A. Authorea Preprints. 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 57.The receipt of industry payments is associated with prescribing promoted alpha-blockers and overactive bladder medications. Modi PK, Wang Y, Kirk PS, Dupree JM, Singer EA, Chang SL. Urology. 2018;117:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Physician payments from industry are associated with greater Medicare Part D prescribing costs. Perlis RH, Perlis CS. PLoS One. 2016;11:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and prescriptions of biologics for asthma. Murayama A. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patients' awareness of and attitudes toward gifts from pharmaceutical companies to physicians. Jastifer J, Roberts S. Int J Health Serv. 2009;39:405–414. doi: 10.2190/HS.39.2.j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Awareness and attitudes of the Lebanese population with regard to physician-pharmaceutical company interaction: a survey study. Ammous A, Bou Zein Eddine S, Dani A, Dbaibou J, El-Asmar JM, Sadder L, Akl EA. BMJ Open. 2017;7:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Awareness and perceptions among members of a Japanese cancer patient advocacy group concerning the financial relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and physicians. Murayama A, Senoo Y, Harada K, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of patients and the general public towards the interactions of physicians with the pharmaceutical and the device industry: a systematic review. Fadlallah R, Nas H, Naamani D, et al. PLoS One. 2016;11:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The effects of pharmaceutical firm enticements on physician prescribing patterns. There's no such thing as a free lunch. Orlowski JP, Wateska L. Chest. 1992;102:270–273. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians' prescribing: a systematic review. Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, Lexchin J, Doust J, Othman N, Vitry AI. PLoS Med. 2010;7:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Research and nonresearch industry payments to nephrologists in the United States between 2014 and 2021. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Kugo H, Saito H, Ozaki A. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023 doi: 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Industry payments to pathologists in the USA between 2013 and 2021. Murayama A, Hirota S. J Clin Pathol. 2023;76:566–570. doi: 10.1136/jcp-2023-208901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trend in industry payments to rheumatologists in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic between 2013 and 2021. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Higuchi K, Shigeta H, Ozaki A. J Rheumatol. 2023;50:575–577. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.220512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Industry payments to allergists and clinical immunologists in the United States during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Saito H, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:635–636. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Self-reported financial conflict of interest in nephrology clinical practice guidelines. Chengappa M, Herrmann S, Poonacha T. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Evaluation of financial conflicts of interest among physician-authors of American College of Rheumatology clinical practice guidelines. Wayant C, Walters C, Zaaza Z, Gilstrap C, Combs T, Crow H, Vassar M. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:1427–1434. doi: 10.1002/art.41224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reporting of financial conflicts of interest by Canadian clinical practice guideline producers: a descriptive study. Elder K, Turner KA, Cosgrove L, et al. CMAJ. 2020;192:0–25. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Financial conflicts of interest among National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guideline panelists in 2019. Desai AP, Chengappa M, Go RS, Poonacha TK. Cancer. 2020;126:3742–3749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Industry payments to physician journal editors. Wong VS, Avalos LN, Callaham ML. PLoS One. 2019;14:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Payments by US pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to US medical journal editors: retrospective observational study. Liu JJ, Bell CM, Matelski JJ, Detsky AS, Cram P. BMJ. 2017;359:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Undisclosed financial ties between guideline writers and pharmaceutical companies: a cross-sectional study across 10 disease categories. Moynihan R, Lai A, Jarvis H, Duggan G, Goodrick S, Beller E, Bero L. BMJ Open. 2019;9:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Discrepancies in self-reported financial conflicts of interest disclosures by physicians: a systematic review. Taheri C, Kirubarajan A, Li X, Lam AC, Taheri S, Olivieri NF. BMJ Open. 2021;11:0. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Undisclosed payments by pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to authors of endoscopy guidelines in the United States. Bansal R, Khan R, Scaffidi MA, et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Undisclosed financial conflicts of interest among authors of American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guidelines. Saleh RR, Majeed H, Tibau A, Booth CM, Amir E. Cancer. 2019;125:4069–4075. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Financial conflicts of interest between pharmaceutical companies and the authors of urology clinical practice guidelines in Japan. Yamamoto K, Murayama A, Ozaki A, Saito H, Sawano T, Tanimoto T. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:443–451. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Evaluation of financial conflicts of interest and drug statements in the coronavirus disease 2019 clinical practice guideline in Japan. Hashimoto T, Murayama A, Mamada H, Saito H, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:460–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Financial and intellectual conflicts of interest among Japanese clinical practice guidelines authors for allergic rhinitis. Murayama A, Kida F, Ozaki A, Saito H, Sawano T, Tanimoto T. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166:869–876. doi: 10.1177/01945998211034724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Letter to the editor: Are clinical practice guidelines for hepatitis C by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America evidence based? Financial conflicts of interest and assessment of quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Murayama A, Ozaki A, Saito H, Sawano T, Tanimoto T. Hepatology. 2022;75:1052–1054. doi: 10.1002/hep.32262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Evaluation of conflicts of interest among participants of the Japanese nephrology clinical practice guideline. Murayama A, Yamada K, Yoshida M, et al. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:819–826. doi: 10.2215/CJN.14661121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Professional medical associations and their relationships with industry: a proposal for controlling conflict of interest. Rothman DJ, McDonald WJ, Berkowitz CD, et al. JAMA. 2009;301:1367–1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guidelines International Network: principles for disclosure of interests and management of conflicts in guidelines. Schünemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:548–553. doi: 10.7326/M14-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Analysis of conflict of interest policies among organizations producing clinical practice guidelines. Brems JH, Davis AE, Clayton EW. PLoS One. 2021;16:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Evaluation of financial conflicts of interest and quality of evidence underlying the American Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, 2021. Shigeta H, Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Saito H, Ozaki A. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]