Abstract

A PCR test based on the amplification of an eae-specific sequence was designed and evaluated for its ability to directly detect homologous sequences in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Citrobacter spp. (amplification of eae open reading frame, 178 bp) in sections of the intestines of humans and animals with colonic lesions. Positive PCR results were observed with eae-positive reference strains of E. coli and Citrobacter rodentium (Citrobacter freundii biotype 4280). Known eae-negative reference strains of E. coli and other laboratory strains of enteric bacteria were negative by the amplification test. The sensitivity of the PCR for detection of eae-positive E. coli and C. rodentium was between 1 and 2 CFU. To detect these sequences directly from sections of fixed colon from human and veterinary sources, PCR conditions were modified by the addition of 0.1 mM 8-methoxypsoralen to eliminate extraneous bacterial DNA from the PCR amplification cocktail without added template. Sections of colon from three pigs experimentally affected with colon lesions due to enteropathogenic (attaching and effacing) E. coli were PCR positive for bacterial eae genome. Sections from control animals were negative. Sections of colon from one of 18 biopsies from confirmed AIDS patients and from 22 of 35 colorectal cancer patients were PCR positive for bacterial eae genome. The PCR test was a simple and quick method of detecting bacterial eae genome in human and veterinary clinical specimens. This method may remove the need for initial culture and detection of the gene by DNA probing from potential associated lesions. The clear relationship of bacteria containing the eae gene with colonic lesions in the pigs and mice indicates that a similar relationship is possible for human patients having similar lesions.

Mammalian colons normally maintain a large, complex bacterial flora. Many species within the flora are poorly characterized anaerobes, making identification of specific enteropathogenic bacteria in the colon difficult. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli capable of causing attaching and effacing lesions in the epithelial cells of the mucosa of the colon have been characterized in humans and in pigs and other animals (11, 15, 23, 27). Previous isolations of Citrobacter freundii and enteropathogenic E. coli from human colon have been associated with symptoms associated with lesions of acute enteritis (26). Whether these organisms are capable of contributing to chronic or subclinical enteric disease in humans is not clear.

It has been suggested that colonic bacteria may also be involved in the initiation of colonic hyperplasia and, ultimately, colonic cancer in humans (19, 25). Studies of colonic infection by Lawsonia intracellularis (family Desulfovibrionaceae) in pigs and Citrobacter rodentium (C. freundii biotype 4280) in mice have shown a causal relationship between the presence of the bacteria and hyperplasia of intestinal epithelial cells (13, 22). Both C. rodentium and enteropathogenic E. coli have an active eae gene, contributing to their attachment and virulence in the colon (5, 22). The eae gene cluster encodes a 94-kDa protein essential for characteristic intimate colonization and local cellular disruption (9). We therefore developed a sensitive and specific PCR for eae-positive bacteria which could be carried out with fixed specimens such as those obtained by biopsy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

In order to initially assess the efficacy and specificity of the PCR test for eae-positive bacteria, we used three representative bacteria, C. rodentium (C. freundii biotype 4280), enteropathogenic E. coli 5102/96 (eae positive), and nonpathogenic E. coli 9472/10 (eae negative). All these bacteria were obtained from the culture collection of the Veterinary Laboratories Agency, Addlestone, Surrey, United Kingdom. Following clonal isolation on nutrient agar plates, CFU from all bacteria were cultured at 37°C in broths of standard nutrient medium (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing no animal blood. In separate tests, liquid gelatin was added to portions of 24-h broth cultures of each of the representative strains to a final volume of 10% to solidify the cultures for sectioning. A 0.1-ml portion of each semisolid culture was added to melted paraffin and embedded in a separate histology cassette. Thirty-eight additional laboratory strains of enteric and other bacteria were also tested for the eae gene by PCR (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains tested for the presence of the eae gene by nested PCR

| Bacterium | Strain no. | Strain origina | eae PCR result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 447/82 D524 3 | Bovine feces | Positive |

| 5102/96P | Bovine feces | Positive | |

| 499/82 11 | Ovine feces | Positive | |

| 579/73 | Porcine feces | Positive | |

| O116 | Porcine feces | Positive | |

| 248/82 D360 3 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 249/82 44 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 496/82 D532 6 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 513/82 D53A 15CR | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 555/82 D832 8R | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 1660/81 727 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 9472/10 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 219/82 44 | Equine feces | Negative | |

| 32/82 N47 R | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli | B41 K99 | Bovine feces | Negative |

| B44 K99 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 947240 K99 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| Campylobacter fetus | 437/73 | Ovine fetus | Negative |

| NCTC 5850 | Ovine fetus | Negative | |

| Campylobacter lari | 357/90 | Avian feces | Negative |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 88/82 B | Bovine feces | Negative |

| 127/82 D128 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 127/82 D128 7C | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 127/82 D128 14C | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 191/82 276 C1 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 213/82 D128 20 C NS | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| D141 26 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 285/82 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 7C-R | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 1716/81 | Bovine feces | Negative | |

| 1097/75 10-537 | Human feces | Negative | |

| 32/82 24 | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| 291/82 24 | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| 291/82 27 | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| 291/82 29 | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| 389/82 7 | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| 441/82 D338 8C | Ovine feces | Negative | |

| 1386/76 U1-E | Porcine feces | Negative | |

| Citrobacter rodentium (freundii) | 4280 | Murine intestine | Positive |

| 655/80 | Murine intestine | Positive | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | B45/95 | Bovine milk | Negative |

| Streptococcus dysgalactea | M37896 | Bovine milk | Negative |

| Streptococcus zooepidemicus | M49/87 | Equine skin | Negative |

All isolates originated from animals located in Scotland, except C. rodentium 655/80, which was isolated from mice in the United States, C. fetus NCTC 5850, which was isolated in Cambridge, United Kingdom, and C. rodentium biotype 4280, E. coli 5102/96P, and E. coli 9472/10, obtained from the culture collection of the Veterinary Laboratories Agency.

Human and veterinary clinical samples.

In this study we included samples of formalin-fixed colon as direct clinical material for the PCR protocols, taken at necropsy from control pigs (n = 3) and from pigs experimentally affected with attaching and effacing lesions of the intestine due to eae-positive E. coli O116 (n = 3) as described earlier (16). For these sections we also visualized the relative numbers of E. coli O116 attached to the epithelial cells within each lesion by examining additional sections from each colon in an indirect immunoperoxidase assay incorporating primary rabbit antibody into E. coli O116 (16). The human clinical samples included specimens taken from the colons of patients with AIDS at autopsy, which were collected in Edinburgh between 1990 and 1995 (n = 18) as described earlier (20). We also included surgical biopsies taken from the colons of patients with operable colorectal cancer, which were collected from local hospitals between 1988 and 1993 (n = 35). All cases were classified as Dukes stage A (early) cancer progression by standard histopathologic methods. In all human and veterinary clinical material, colon tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. For all specimens, standard 4-μm-thick sections adjacent to those taken for PCR analysis were prepared and stained with routine hematoxylin and eosin stain and Gram stain.

DNA template preparation.

Bacterial DNA was prepared from pelleted bacteria of each cultured strain by standard methods (10). DNA from paraffin-embedded sections of cultured bacteria or clinical material was prepared for PCR by a modification of a boiling lysis method (6). Briefly, four 10-μm-thick sections from each sample were transferred to separate microcentrifuge tubes, with a fresh knife used for each specimen. A 0.1-ml portion of an aqueous lysis buffer, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.4), 1 mM Na2–EDTA, 0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (polyoxyethylene [20] sorbitan monolaurate), with added 0.1 mM 8-methoxypsoralen (MOPS) (14) was exposed to UV light (365 nm) for 5 min. MOPS-treated lysis buffer (0.1 ml) was then added to each tube containing paraffin sections and heated to 100°C for 30 min for a resulting DNA solution. Samples of cultures and tissues were prepared in a separate room from that in which subsequent PCR tests were carried out, and sterile disposable gloves, sterile nonpyrogenic water, and positive displacement pipettes with sterile filter tips were systematically used.

PCR.

The PCR was completed in microcentrifuge tubes (Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany) for the Hybaid Omnigene thermocycler. The PCR mixture contained 10× PCR buffer (500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9], 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM MOPS), 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide mixture (Pharmacia Ltd., Uppsala, Sweden), 4% dimethylsulfoxide, 200 ng of each primer, and 2 U of Taq polymerase (Promega Ltd., Minneapolis, Minn.). Aliquots of the reaction mixture (45 μl each) and 50 μl of MOPS-treated mineral oil were exposed to UV light (365 nm) for 5 min prior to the addition of 5 μl of template DNA (50 μl of final reaction volume). Each primer was designed from the open reading frame of published eae gene sequences from three different bacterial strains deposited in GenBank: E. coli, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and C. rodentium (accession no. M58154, Z11541, and L11691, respectively). The primer pair P1 (5′-ATTATGGAACGGCAGAGG-3′, sense [nucleotides 694 to 711]) and P2 (5′-GGAAGGAAAAAACGCTGAC-3′, antisense [nucleotides 873 to 852]) and pair P3 (5′-GAGTGGTAATAACTTTGACGG-3′, sense [nucleotides 702 to 722]) and P4 (5′-GTAAAGCGGGAGTCAATG-3′, antisense [nucleotides 835 to 818]) generated fragments of 179 and 133 bp, respectively. The specificity of these fragments for the eae gene was confirmed by the >99% homology of nucleotides identified by direct sequencing of each fragment to the published sequence (GenBank accession no. Z11541). These primer sequences were chosen from a region of high homology in the eae gene between Citrobacter spp. and enteropathogenic E. coli. The presence of bacterial DNA in each sample was confirmed by the incorporation of a 5-μl sample of each template DNA into a PCR amplification of bacterial ribosomal DNA fragments with primers p11E (5′ GAGGAAGGTGGGGATGACG 3′) and p13B (5′ AGGCCCGGGAACGTATTCAC 3′), specific for all known eubacterial genera, as described previously (18). Cycling parameters for each primer set are outlined in Table 2. To increase sensitivity of eae detection, nested PCR was performed. Each sample underwent 38 cycles of PCR amplification with primers P1 and P2. One microliter of product from this reaction was used as template in the nested reaction of 25 cycles of PCR with primers P3 and P4. The additions of MOPS were intended to decontaminate nonsample reaction components of extraneous bacterial DNA (14). PCR products were separated by size by electrophoresis through 1.8% (wt/vol) Metaphor agarose gel (Pharmacia Ltd.) and visualized after staining with ethidium bromide on a UV transilluminator. All batches of PCRs included separate tubes with DNA from E. coli 5102/96P and 9472/10 and a reaction mixture with water instead of template DNA.

TABLE 2.

PCR cycling conditions used with eae detection primer set P1 and P2 and set P3 and P4 and eubacterial 16S primers p11E and p13B

| Primer set | Time at denaturing at 94°C | Annealing | Time at extension at 72°C | No. of cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1/P2 | 30 s | 55°C for 20 s | 20 s | 38 |

| P3/P4 | 1 min | 50°C for 1 min | 1 min | 25 |

| p11E/p13B | 1 min | 55°C for 1 min | 1.5 min | 38 |

To distinguish the origin of eae-positive PCR product from human specimens, restriction digestion of PCR product from reactions incorporating primer pair P1 and P2 was performed. The DNA sequences of 179-bp PCR product from the eae genes derived from a Citrobacter sp. and E. coli differ in an area including a restriction site to AciI in the E. coli DNA. Digestion of the PCR product with this enzyme therefore produces either one (179 bp) or two (132 and 47 bp) bands, respectively.

Determination of the lower detection limit.

Serial dilutions were made of 24-h broth cultures of each of the three representative bacterial strains in sterile water to determine the sensitivity of the PCR test for the eae gene. Ten microliters of each dilution was immediately plated onto duplicate nutrient agar plates and incubated at 37°C. Subsequent colonies were counted to determine the number of CFU per dilution by standard Miles-Misra calculations. Two microliters of each dilution was used as template DNA for the PCRs in concurrent tests.

RESULTS

Elimination of nonsample DNA.

Preliminary testing of lysis buffers, PCR components, and mineral oils without added MOPS or UV light exposure regularly detected PCR fragments, with reactions incorporating primers p11Ep and p13B for eubacterial ribosomal DNA but not with the primers for eae DNA (data not shown). The addition of MOPS and exposure to UV light as described for each of these components, except the template DNA, gave no detectable PCR products with any set of test primers with negative control samples, indicating the successful removal of extraneous bacterial DNA.

Specific PCR for eae.

PCRs incorporating primer pair P1 and P2 and pair P3 and P4 and nested reactions resulted in the amplification of eae-specific sequences from DNA prepared from pelleted and paraffin-embedded cultures of the C. rodentium (C. freundii biotype 4280) and enteropathogenic E. coli 5102/96p strains tested, whereas similar preparations from the control E. coli 9472/10 showed no amplified product with these primers. There was no apparent difference in the reaction efficiency for DNA between C. rodentium and E. coli 5102/96P in these eae tests. Thirty-eight other enteric bacteria were tested for eae-specific product by nested PCR, and the results are shown in Table 1. In addition to the reference strains described above, four strains—three E. coli and one Citrobacter—were eae positive, originating from bovine, ovine, porcine, and murine isolates, respectively. PCRs incorporating primer pair p11Ep and p13B showed amplified product with all these bacterial DNAs.

A clear PCR signal was observed up to the dilution that yielded between 50 and 70 CFU per plate for primers P1 and P2 and between 5 and 7 CFU for primers P3 and P4 in a nested PCR, indicating detection sensitivities of approximately 10 bacteria and 1 bacterium, respectively, per PCR. Although PCR with P3 and P4 was more sensitive, the larger fragment amplified by P1 and P2 enabled the performance of subsequent restriction digestions. Digestion of PCR products from eae sequences of Citrobacter spp. and E. coli with AciI resulted in a single fragment for Citrobacter spp. and two fragments (132 and 47 bp) for E. coli eae digestions.

Specific eae gene product was detected following PCRs incorporating primer pair P3 and P4 in colonic biopsies from each of the three pigs experimentally infected with enteropathogenic E. coli but not from the control pigs (Fig. 1). Numerous colonies of gram-negative bacilli attaching to the epithelial cells of the colons in the three pigs positive for the eae gene were visualized in areas affected by effacing lesions. These bacteria had clear positive reactions with rabbit antibody anti-E. coli O116 in immunoperoxidase assays (Fig. 2). There was an absence of similar attaching bacteria and lesions in control pigs.

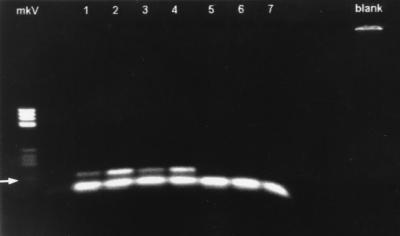

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel (1.8%) illustrating eae-specific PCR products from three pigs infected with E. coli O116 (lane 1, proximal colon; lanes 2 to 4, cecum) and three negative control pigs (lanes 5 to 7, proximal colon). The arrow indicates an eae-specific PCR product of 133 bp, and the lower band represents primer dimer complex present in all lanes containing samples. Lane mkV contains Boehringer molecular weight marker V. The blank lane contains a negative control for the PCR.

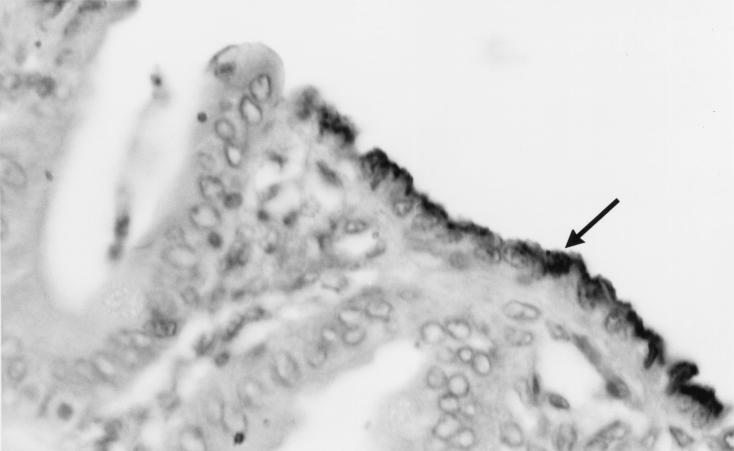

FIG. 2.

Micrograph of a 4-μm-thick section of proximal colon of a pig infected with E. coli O116. E. coli bacteria were stained in an indirect immunoperoxidase assay incorporating primary rabbit antibody with this strain. The arrow indicates positively stained bacteria.

eae PCR of clinical samples.

The nested E. coli PCR results obtained from DNA prepared from sections of colon biopsies of patients with AIDS or colorectal cancer indicated that one of 18 of AIDS patients and 22 of 35 (63%) of Dukes stage A colorectal cancer patients were positive for the eae gene. AciI digestion of eae product of positive patients (n = 3) indicated that the products were consistent with E. coli eae. Single primer pair PCRs for eae did not result in positive results with any clinical specimen. There was no histologic evidence of attaching and effacing lesions in the mucosal epithelium examined with any of these samples. Gram-stained sections of all these samples showed a variety of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in the colonic lumen, within the mucus in the colonic lumen, and associated with the colonic epithelium.

DNA prepared from all fixed colon specimens, pig and human, was positive for PCR product with primer pair p11Ep and p13B for eubacterial ribosomal DNA, indicating the integrity of template DNA and the absence of inhibitory factors in PCRs.

DISCUSSION

This study describes a method of detection of eae-positive bacteria in colon samples collected at biopsy or necropsy. Our preliminary results indicate the presence of eae-positive bacteria in a proportion of AIDS patients and colorectal cancer patients. The accuracy of these preliminary results was confirmed by initial examination of pure cultures of control bacteria and samples from a valid animal model of colonic disease caused by bacteria carrying eae. Samples from the cultures and pig colons reacted in a consistent and specific manner, depending on the presence or absence of bacteria with the eae gene. We therefore suggest that the preliminary result in the human colon samples offers interesting insights into the possible role of eae-positive bacteria in chronic enteric diseases.

The results with human colon samples suggest that eae-positive bacteria are present in the diseased human colon. The source of these bacteria may be dietary or environmental, such as contact with human or animal feces. Our preliminary results suggest that eae-positive bacteria may be more common in cancer patients than in patients with AIDS, but we did not include a human case control group for either disease. While our animal model results are supportive, and while eae-positive bacteria have been clearly associated with acute enteritis in humans and in animals (11, 23, 27) as well as with hyperplasia of colon epithelial cells in a murine model (21), it remains to be established whether there is a causal relationship between eae-positive bacteria and chronic enteric disease in humans. Our results may merely indicate that the colonic environment in colorectal cancer patients is more conducive to the life cycle of eae-positive bacteria. While we did not identify definite chronic or epithelial lesions attributable to eae-positive bacteria, the presence of these bacteria raises the possibility that bacteria living in the diseased human colon can carry virulence factors capable of marked epithelial cell disruption. The eae gene is important for bacterial attachment to intestinal epithelial cells. In vitro studies of cell-bacterial interactions have demonstrated that eae-isogenic strains of bacteria do not attach in the absence of eae but that bacterial and cellular proliferation rates are not affected (21). Several other virulence genes and bacterial attachment mechanisms have also been identified in enteric bacteria, such as the inv gene in Yersinia spp. (8), but eae has been the only gene identified from bacteria capable of causing the proliferation of epithelial cells in the colon of a monogastric mammal (21).

Eae-positive bacteria have been commonly associated with acute diarrhea in infants in developing countries (11), but it is clear from this study and other recent studies that these bacteria are present not only in European and American populations (1, 24) but also in patients with colon disease. Acute enteric disease is a major complication of human immunodeficiency disease, and eae-positive bacteria have been reported in 17% of AIDS patients in New York City (12). We have found a similar frequency of eae-positive bacteria in AIDS patients in the United Kingdom. This finding may reflect opportunistic infection in immunosuppressed individuals but is an unlikely explanation for the presence of eae-positive bacteria in colorectal cancer cases. It is possible that eae-positive E. coli possesses capabilities similar to those of Helicobacter pylori (declared by the International Agency for Research on Cancer to be a group 1 carcinogen, a definite cause of human cancer [7]), causing increased cellular proliferation and inflammation (4). Animals infected with C. rodentium develop colonic hyperplasia and, when exposed to exogenous mutagens, progress more rapidly to malignancy than uninfected animals (2, 3). It is possible to speculate that cell disruptions associated with the eae virulence gene play a role in the pathogenesis of colon cancer and its progression in some cases.

Direct PCR for bacterial gene detection in histologic samples is an efficient new tool for the study of attaching and effacing bacteria and may be applicable to many other bacterial infections. Direct PCR has reduced the need for bacterial culture and allowed the use of archival specimens. This type of PCR can be carried out in less than 1 day. However, it is vital to eliminate extraneous DNA by rigorous removal of DNA from all nonsample reagents. Bacterial DNA was apparently a common contaminant of laboratory reagents and buffers in this and other studies (14).

The eae sequence used for primer design was considered to be both sensitive and specific. We examined sequences of eae from three different bacterial strains, E. coli, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and C. rodentium (GenBank accession no. M58154, Z11541, and L11691, respectively), and the primers were designed from a highly conserved region. It is therefore likely that this PCR would not be restricted to the eae gene of these bacterial species, meaning that it could have detected additional eae-positive species. Our biochemical identification of species did not indicate this, however. The subsequent use of restriction enzyme digestion allowed the tentative identification of the bacterial source compared to the appropriate control DNA directly from clinical material. This gene-targeted approach to bacterial identification in clinical samples could allow the presumptive identification of bacterial pathogens. Direct PCR may also provide an initial general test to explore the distribution and histological consequences of potential pathogens in clinical samples.

Direct PCR could also provide a method to collect more general information about the genetic content of populations of animal bacteria. Other PCR studies have indicated that the number of bacteria located on and within the bodies of living animals may be much higher than estimates obtained by previous culture-based methods (17). The use of targeted-gene identification may clarify the possible role of some of these new bacteria. Bacterial species could be subsequently identified by additional PCR techniques or by immunohistochemistry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Cancer Research Campaign, grant no. SP2288.

We thank Natasha Neef, Heratio Terzolo, David Sherwood, and John Sullivan for their help with this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agin T S, Wolf M K. Identification of a family of intimins common to Escherichia coli causing attaching-effacing lesions in rabbits, humans, and swine. Infect Immun. 1997;65:320–326. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.320-326.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthold S W, Jonas A M. Morphogenesis of early 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced lesions and latent period reduction of colon carcinogenesis in mice by a variant of Citrobacter freundii. Cancer Res. 1977;37:4352–4360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthold S W, Osbaldiston G W, Jonas A M. Dietary, bacterial, and host genetic interactions in the pathogenesis of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Lab Anim Sci. 1977;27:938–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenes F, Ruiz B, Correa P, Hunter F, Rhamakrishnan T, Fontham E, Shi T Y. Helicobacter pylori causes hyperproliferation of the gastric epithelium: pre- and post-eradication indices of proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1870–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnenberg M S, Tzipori S, McKee M L, O’Brien A D, Alroy J, Kaper J B. The role of the eae gene of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in intimate attachment in vitro and in a porcine model. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1117–1118. doi: 10.1172/JCI116718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubbard A L, Anderson T J. Simple 10 minute preparation of fixed, embedded breast tissue for the polymerase chain reaction. Breast. 1993;2:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC (Int Agency Res Cancer) 1994;61:177–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. Molecular determinants of Yersinia pathogenesis. Microbiologica. 1996;12:267–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerse A E, Kaper J B. The eae gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes a 94-kilodalton membrane protein, the expression of which is influenced by the EAF plasmid. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4302–4309. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4302-4309.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junhui Z, Ruifu Y, Jianchun L, Songle Z, Meiling C, Fengxiang C, Hong C. Detection of Francisella tularensis by the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:477–482. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-6-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knutton S, Phillips A D, Smith H R, Gross R J, Shaw R, Watson P, Price E. Screening for enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in infants with diarrhea by the fluorescent-actin staining test. Infect Immun. 1991;59:365–371. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.365-371.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotler D P, Giang T T, Thiim M, Nataro J P, Sordillo E M, Orenstein J M. Chronic bacterial enteropathy in patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:552–558. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McOrist S, Gebhart C J, Boid R, Barns S M. Characterization of Lawsonia intracellularis gen. nov., sp. nov., the obligately intracellular bacterium of porcine proliferative enteropathy. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:820–825. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier A, Persing D H, Kinken M, Bottger E C. Elimination of contaminating DNA within polymerase chain reaction reagents: implications for a general approach to detection of uncultured pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:646–652. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.646-652.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon H W, Whipp S C, Argenzio R A, Levine M M, Giannella R A. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestine. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neef N A, McOrist S, Lysons R J, Bland A P, Miller B G. Development of large intestinal attaching and effacing lesions in pigs in association with the feeding of a particular diet. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4325–4332. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4325-4332.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podzorski R P, Persing D H. Molecular detection and identification of microorganisms. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 130–157. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Relman D A, Loutit J S, Schmidt T M, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis: an approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1573–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberton A M. Roles of endogenous substances and bacteria in colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 1993;290:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90034-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santosh C G, Bell J E, Best J J. Spinal tract pathology in AIDS: postmortem MRI correlation with neuropathology. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00588630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schauer D B, Falkow S. The eae gene of Citrobacter freundii biotype 4280 is necessary for colonization in transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4654–4661. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4654-4661.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schauer D B, Zabel B A, Pedraza I F, O’Hara C M, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J. Genetic and biochemical characterization of Citrobacter rodentium sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2064–2068. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2064-2068.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scotland S M, Willshaw G A, Smith H R, Said B, Stokes N, Rowe B. Virulence properties of Escherichia coli strains belonging to serogroups O26, O55, O111 and O128 isolated in the United Kingdom in 1991 from patients with diarrhea. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:429–438. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen W, Steinruch H, Ljungh A. Expression of binding of plasminogen, thrombospondin, vitronectin, and fibrinogen, and adhesive properties by Escherichia coli strains isolated from patients with colonic diseases. Gut. 1995;36:401–406. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Werf S D J, Nagengast F M, Van der Berge Henegouwen G P, Huijbregts A W, Van Tongeren J H M. Intracolonic environment and the presence of colonic adenomas in man. Gut. 1983;24:876–880. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.10.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanhoof R, Content J, Van Bossuyt E, Nulens E, Sonck P, Depuydt F, Hubrechts J M, Maes P, Hannecart-Pokorni E. Use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the detection of aacA genes encoding aminoglycoside-6′-N-acetyltransferases in reference strains and Gram-negative clinical isolates from two Belgium hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:23–35. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada Y, Kondo H, Nakaoka Y, Kubo M. Gastric attaching and effacing Escherichia coli lesions in a puppy with naturally occurring enteric colibacillosis and concurrent canine distemper virus infection. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:717–720. doi: 10.1177/030098589603300615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]