Abstract

Background

There are several approaches to THA, and each has their respective advantages and disadvantages. Previous meta-analysis included non-randomised studies that introduce further heterogeneity and bias to the evidence presented. This meta-analysis aims to present level I evidence by comparing functional outcomes, peri-operative parameters and complications of direct anterior approach (DAA) versus posterior approach (PA) or lateral approach (LA) in THA.

Patients and methods

A comprehensive multi-database search (PubMed, OVID Medline, EMBASE) was conducted from date of database inception to 1st December 2020. Data from randomised controlled trials comparing outcomes of DAA versus PA or LA in THA were extracted and analysed.

Results

Twenty-four studies comprising 2010 patients were included in this meta-analysis. DAA has a longer operative time (MD = 17.38 min, 95%CI: 12.28, 22.47 min, P < 0.001) but a shorter length of stay compared to PA (MD = − 0.33 days, 95%CI: − 0.55, − 0.11 days, P = 0.003). There was no difference in operative time or length of stay when comparing DAA versus LA. DAA also had significantly better HHS than PA at 6 weeks (MD = 8.00, 95%CI: 5.85, 10.15, P < 0.001) and LA at 12 weeks (MD = 2.23, 95%CI: 0.31, 4.15, P = 0.02). There was no significant difference in risk of neurapraxia for DAA versus LA or in risk of dislocations, periprosthetic fractures or VTE between DAA and PA or DAA and LA.

Conclusion

The DAA has better early functional outcomes with shorter mean length of stay but was associated with a longer operative time than PA. There was no difference in risk of dislocations, neurapraxias, periprosthetic fractures or VTE between approaches. Based on our results, choice of THA approach should ultimately be guided by surgeon experience, surgeon preference and patient factors.

Level of evidence I

Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Keywords: Direct anterior approach, Lateral approach, Posterior approach, Posterolateral approach, Total hip arthroplasty, Total hip replacement

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a highly successful treatment for hip osteoarthritis, offering significant pain relief and improved quality of life by restoring function and mobility [1]. THA has shown excellent results over time, with 10-year survivorship exceeding 95% [2]. Annually, over one million THA is performed worldwide and is projected to reach two million by 2030 [1], attributed to the increasing life expectancy and prevalence of osteoarthritis.

There are several surgical approaches to THA, including posterior approach (PA), lateral approach (LA) and direct anterior approach (DAA), all of which have their respective advantages and disadvantages. PA involves splitting of gluteus maximus to access the hip joint posteriorly. PA allows for excellent exposure of both acetabulum and femur and avoids disruption of the hip abductors [3]. However, PA has been associated with an increased dislocation risk compared to LA or DAA [3–5], though this risk can be reduced with careful implant positioning and posterior soft tissue repair [6]. LA involves splitting of gluteus medius to access the hip joint anterolaterally. It has a lower risk of dislocation but is associated with superior gluteal nerve injury, heterotopic ossification and impaired abductor function [3]. DAA is unique with its inter-nervous and intermuscular plane between sartorius and tensor fascia latae, leading to increasing popularity as a THA approach [3]. Reported advantages include shorter hospital stay [7], earlier functional recovery [8] and lower dislocation risks [9]. Disadvantages include risk of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) injury [10], periprosthetic fractures [11] and the presence of a prolonged learning curve of 100 cases [12, 13].

There is ongoing debate with no clear consensus on the most optimal THA approach. Although several meta-analyses on this subject have previously been published, these meta-analyses had included non-randomised controlled trials (RCT) [4, 5, 8, 11, 14–17] which limit the quality of evidence presented since selection and recall bias cannot be excluded. Hence, an updated meta-analysis incorporating only RCTs would be of value to present the highest evidence level.

This meta-analysis aims to present level I evidence by evaluating and comparing 1. functional outcomes, 2. peri-operative parameters and 3. complications of DAA versus LA or PA in THA.

Material and methods

Literature search

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria. A comprehensive multi-database search (PubMed, OVID Medline, EMBASE) was conducted from date of database inception to 1st December 2020. The Medical Subject Headings and Boolean operators utilized were: [(‘Total hip arthroplasty’ OR ‘Total hip replacement’) AND (Approach)]. Results were subsequently filtered for RCTs. Identified articles and their corresponding references were reviewed and considered for inclusion according to the selection criteria.

Selection criteria

All RCTs directly comparing outcomes of DAA versus LA or PA in THA were considered for inclusion. Non-English language studies, non-peer-reviewed studies, conference abstracts, unpublished manuscripts and studies not directly comparing outcomes between THA approaches were excluded. Two independent authors reviewed studies retrieved from the initial search and excluded irrelevant studies. Abstracts and titles of remaining articles were then screened against the inclusion criteria. Included articles were critically reviewed according to a pre-defined data extraction form. Differences in opinions were resolved by discussion between the first two authors.

Data extraction

Extracted data parameters include details on study designs, publication year, patient numbers, basic demographics, peri-operative parameters, functional outcomes and complications. Peri-operative parameters include mean operative time (minutes), mean length of stay (LoS) (days), mean blood loss (millilitres), transfusion requirement, discharge destination and post-operative opioid use. Functional outcomes of interest include Harris Hip Score (HHS), Oxford Hip Score (OHS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index score (WOMAC), EuroQoL 5-Dimension (EQ-5D), Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain scores, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF12), 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF36), University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) activity scores, Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) and timed up and go (TUG). Complications of interest include periprosthetic fractures, dislocations, venous thromboembolism (VTE), neurapraxia, wound dehiscence, superficial infections, deep infections and revisions. Data extracted were organised using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Methodology assessment

Methodology quality of included studies was assessed with the Cochrane collaboration tool for Risk of Bias (RoB) in RCT [18]. Seven criteria were used to assess RCT, and each criterion was scored in three categories. The criterion is rated ‘low risk’ if the criterion is explicitly adhered to, ‘high risk’ if it is not adhered to and ‘unclear risk’ if the criterion is not mentioned. Any discrepancy in risk assessment was resolved by open discussion and a deciding vote from a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

Comparative meta-analysis was performed with odds ratio (OR) and weighted mean difference (MD) primarily used as summary statistics. In this meta-analysis, both fixed- and random-effects models were tested. Fixed-effects model assumed that treatment effects in each study were identical, while random-effects model assumed that variations were present between studies. X2 tests were used to study heterogeneity between studies. I2 statistic was used to estimate the percentage of total variation across studies, owing to heterogeneity rather than chance. Values greater than 50% were regarded as substantial heterogeneity. I2 can be calculated as: I2 = 100% x (Q−df)/Q. Q was defined as Cochrane’s heterogeneity statistics and df defined as degree of freedom. If substantial heterogeneity was present, the possible clinical and methodological reasons were explored qualitatively. This meta-analysis presented results with a random-effects model to account for clinical diversity and methodological variation between studies. All p values were two-sided. Review Manager (version 5.3, Copenhagen, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Literature search

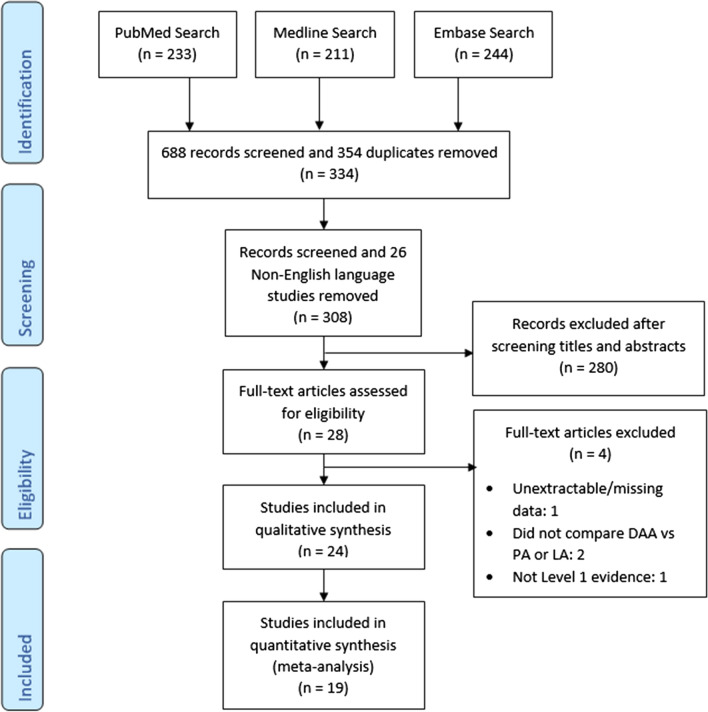

A selection process flowchart to include relevant studies is illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 688 studies were identified from initial search, of which 354 duplicates and 26 non-English language articles were removed. Titles and abstracts of 308 remaining studies were screened according to the pre-defined inclusion criteria, and 280 studies were excluded. Twenty-eight full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Eventually, 24 randomized controlled trials were included of which 12 compared DAA versus PA [19–30] and 12 compared DAA versus LA [31–42].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA search flowchart

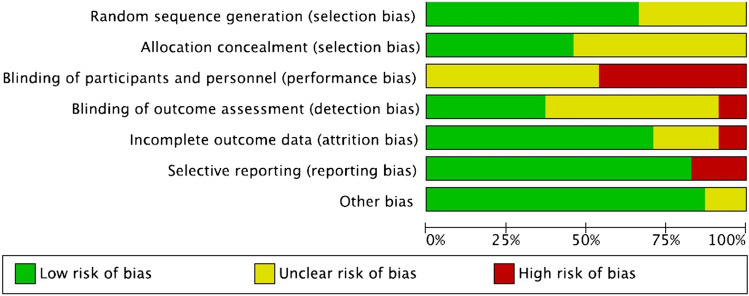

Methodology assessment

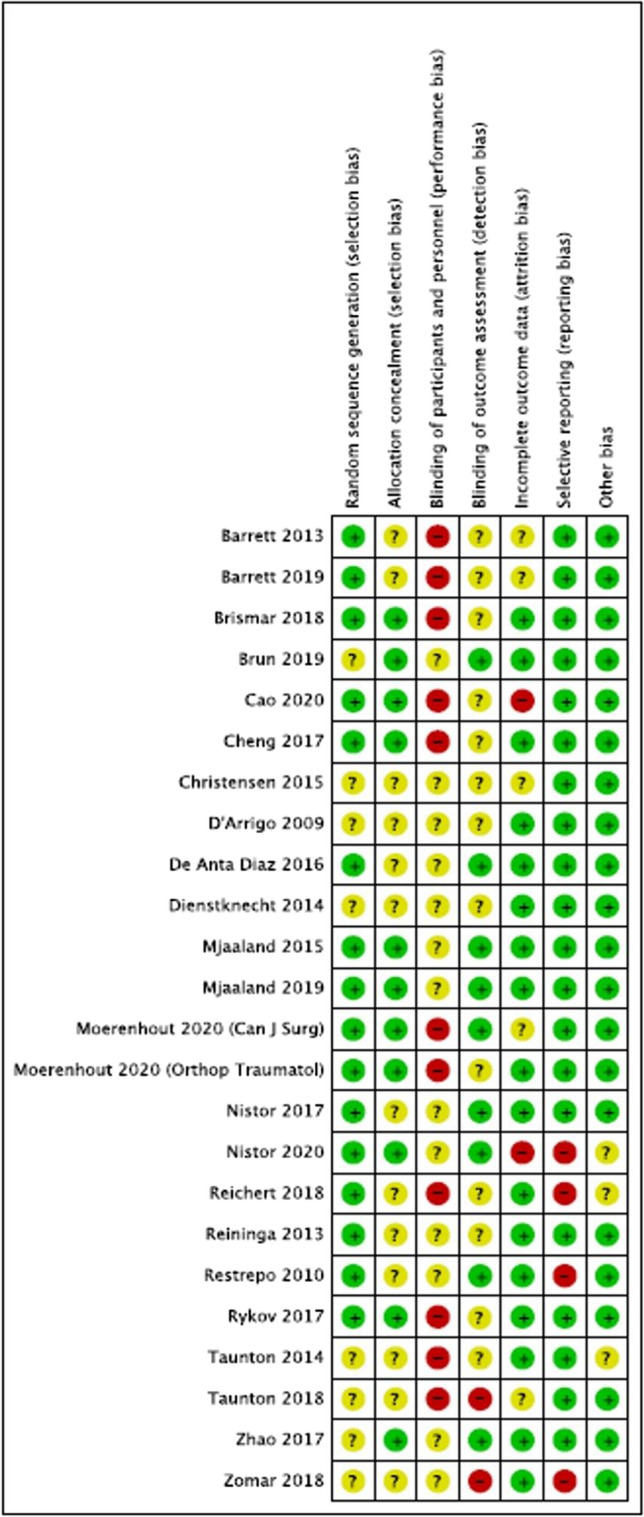

Risk of bias assessment summary and graph for all 24 included RCTs are found in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Sixteen studies had low risk of bias in random sequence generation, while 8 studies had unclear risk. Risk of bias with allocation concealment was low in 11 studies but unclear in 13 studies. All studies had unclear or high risk of bias in blinding of participants and personnel due to nature of intervention. In terms of blinding of outcome assessors, two studies had high risk of bias, 13 had unclear risk, and 9 were low risk. Risk of bias with incomplete outcome data was low in 17 studies, unclear in five studies and high in two studies. Four studies had high risk of bias from selective reporting, while 20 were low risk. Apart from three studies with an unclear risk of other biases, the rest were of low risk.

Table 1.

Risk of bias (RoB) assessment tool summary

Table 2.

Risk of bias (RoB) assessment tool graph

Demographics

A total of 2010 patients were included, with 792 in DAA versus PA and 1218 in DAA versus LA. Comparing DAA versus PA, both DAA and PA groups had 177 males and 219 females. Mean age in the DAA group was 63.5 years, while mean age of PA group was 63.3 years. Comparing DAA versus LA, 236 males and 361 females underwent DAA, while 288 males and 333 females underwent LA. Mean age was 64.7 years for the DAA group and 63.3 years for the LA group. Follow-up period was reported by 23 studies ranging from 4 days to 6.2 years. Other demographic details of each study are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Basic demographics of included studies

| Articles | Year | Study design | No of patients | Mean age | Sex | Follow-up in years (range) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAA vs PA | DAA | PA | DAA | PA | DAA | PA | DAA | PA | ||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||||||

| Barrett | 2013 | RCT | 43 | 44 | 61.4 | 63.2 | 29 | 14 | 19 | 25 | Up to 1 | |

| Barrett | 2019 | RCT | 43 | 44 | 61.4 | 63.2 | 29 | 14 | 19 | 25 | 4.94 | 5.19 |

| Cao | 2020 | RCT | 65 | 65 | 61.4 | 62.4 | 27 | 38 | 28 | 37 | Up to 0.5 | |

| Cheng | 2017 | RCT | 35 | 38 | 59.0* | 62.5* | 15 | 20 | 18 | 20 | Up to 0.25 | |

| Christensen | 2015 | RCT | 28 | 23 | 64.3 | 65.2 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 12 | Up to 0.115 | |

|

Moerenhout (Can J Surg) |

2020 | RCT | 28 | 27 | 70.4 | 68.9 | 11 | 17 | 18 | 9 | 4.583 | |

|

Moerenhout (Orthopaedics and traumatology) |

2021 | RCT | 24 | 21 | 70.3 | 67.7 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 7 | 5.167 (4–6.167) | |

| Reininga | 2013 | RCT | 35 | 40 | 60.3 | 60.5 | 11 | 24 | 8 | 32 | Up to 0.5 | |

| Rykov | 2017 | RCT | 23 | 23 | 62.8 | 60.2 | 8 | 15 | 11 | 12 | Up to 0.115 | |

| Taunton | 2014 | RCT | 27 | 27 | 62.1 | 66.4 | 12 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 1 | |

| Taunton | 2018 | RCT | 52 | 49 | 65.0 | 64.0 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 1.718 | |

| Zhao | 2017 | RCT | 60 | 60 | 64.9 | 62.2 | 24 | 36 | 26 | 34 | Up to 0.5 | |

| DAA vs LA | DAA | LA | DAA | LA | DAA | LA | DAA | LA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||||||

| Brismar | 2018 | RCT | 50 | 50 | 66* | 67* | 18 | 32 | 17 | 33 | Up to 5 | |

| Brun | 2019 | RCT | 84 | 80 | 67.2 | 65.6 | 25 | 59 | 30 | 50 | – | |

| D' Arrigo | 2009 | RCT | 20 | 20 | 64.0 | 66.3 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 6 | Up to 0.115 | |

| De Anta Diaz | 2016 | RCT | 50 | 49 | 64.8 | 63.5 | 26 | 24 | 26 | 23 | 1 | |

| Dienstknecht | 2014 | RCT | 55 | 88 | 61.9 | 61.3 | 22 | 33 | 41 | 47 | 0.25 | |

| Mjaaland | 2015 | RCT | 84 | 80 | 67.2 | 65.6 | 25 | 59 | 30 | 50 | Up to 0.0110 | |

| Mjaaland | 2019 | RCT | 84 | 80 | 67.2 | 65.6 | 25 | 59 | 30 | 50 | Up to 2 | |

| Nistor | 2017 | RCT | 35 | 35 | 67.0* | 64.0* | 9 | 26 | 19 | 16 | 0.25 | |

| Nistor | 2020 | RCT | 56 | 56 | 65.0* | 63.0* | 16 | 40 | 30 | 26 | Up to 0.25 | |

| Reichert | 2018 | RCT | 77 | 71 | 63.2 | 61.9 | 45 | 32 | 39 | 32 | Up to 1 | |

| Restrepo | 2010 | RCT | 50 | 50 | 62.0 | 59.9 | 17 | 33 | 22 | 28 | 2 | |

| Zomar | 2018 | RCT | 36 | 42 | 60.8 | 59.5 | 21 | 15 | 20 | 22 | Up to 0.25 | |

* Values presented in median, '–' Data not available

Clinical outcomes

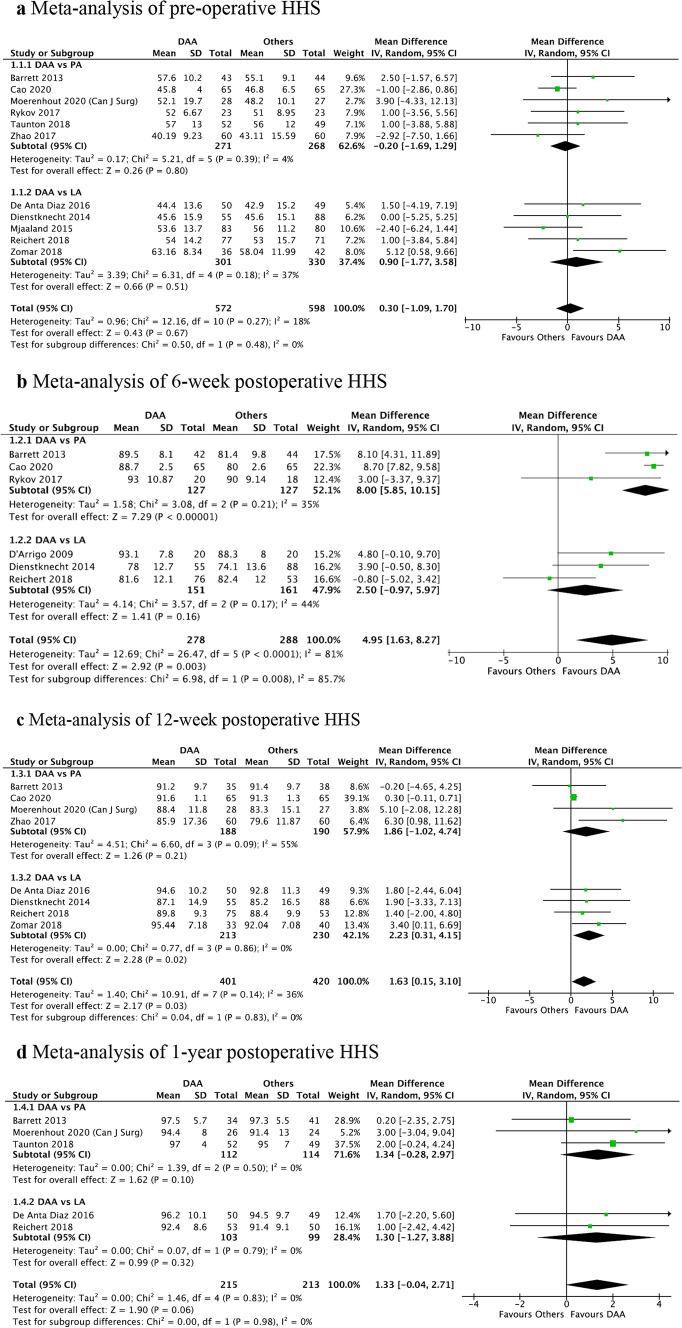

Comparing DAA versus PA, there was a significantly better HHS in the DAA than PA group at 6 weeks (mean difference (MD) = 8.00, 95%CI: 5.85, 10.15, P < 0.001) as seen in Fig. 2b, while pre-op (MD = − 0.20, 95%CI: − 1.69, 1.29, P = 0.80), 12 week (MD = 1.86, 95%CI: − 1.02, 4.74, P = 0.21) and 1-year (MD = 1.34, 95%CI: − 0.28, 2.97, P = 0.10) HHS did not show statistically significant difference (Fig. 2b–d).

Fig. 2.

a Meta-analysis of pre-operative HHS, b meta-analysis of 6-week post-operative HHS, c meta-analysis of 12-week post-operative HHS, d meta-analysis of 1-year post-operative HHS

When comparing DAA versus LA, there was a significantly better HHS in the DAA than LA group at 12 weeks (MD = 2.23, 95%CI: 0.31, 4.15, P = 0.02) as seen in Fig. 2c, while pre-op (MD = 0.90, 95%CI: − 1.77, 3.58, P = 0.51), 6 week (MD = 2.50, 95%CI: − 0.97, 5.97, P = 0.16) and 1-year (MD = 1.30, 95%CI: − 1.27, 3.88, P = 0.32) HHS did not show statistically significant difference (Figs. 2a, b, d).

Due to heterogeneity of PROMS, comparative statistical analysis could only be performed for pre-op, 6-week, 12-week and 1-year HHS. All other functional outcomes are summarised in Appendix 1.

Eleven RCTs discussed pain scores. Seven RCTs reported lower VAS pain scores in the first few days up to 1-week post-operatively for DAA [24, 25, 28, 31, 35, 36, 38]. Four studies noted no significant difference beyond 2 weeks [19, 22, 25, 37]. Cao et al. [27], however, reported lower pain scores for DAA at 3 and 6-weeks when comparing DAA versus PA.

In terms of gait parameters, there were inconsistent results across studies. Comparing DAA versus PA, Zhao et al. reported improved gait recovery at 3 months but not 6 months for DAA, while Reininga et al. [28, 30] reported no difference in locomotor parameters and gait recovery, respectively. Comparing DAA versus LA, Zomar et al. [42] found improved gait velocity, stride length, step length and symmetry at early follow-up favouring DAA.

Radiological

Nine RCTs discussed radiological positioning. Eight RCTs reported no significant difference in radiological positioning of implants between THA approaches [19, 21–23, 32, 35, 38, 40]. However, Zhao et al. [28] concluded that the DAA was associated with more accurate cup positioning.

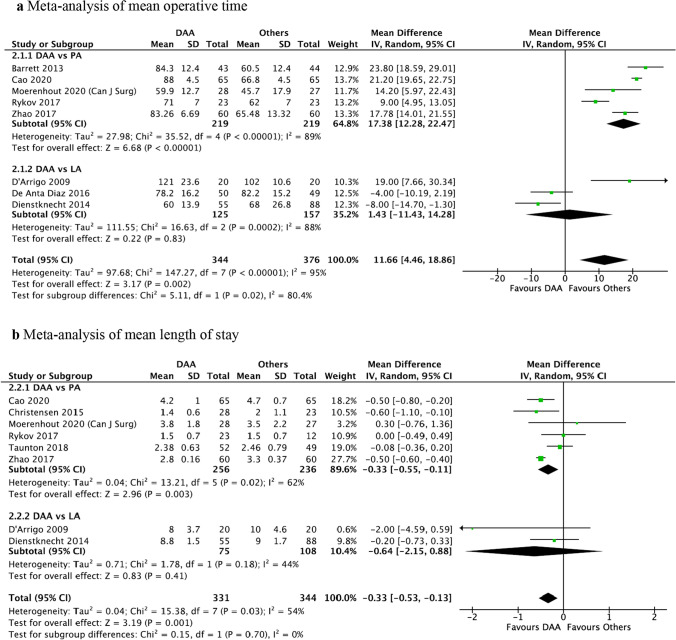

Peri-operative parameters

Mean operative time was significantly longer for DAA compared to PA (MD = 17.38 min, 95%CI: 12.28, 22.47 min, P < 0.001), but there was no significant difference between DAA and LA (MD = 1.43 min, 95%CI: − 11.43, 14.28 min, P = 0.83) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

a Meta-analysis of mean operative time, b meta-analysis of mean length of stay

Mean LoS was significantly shorter for DAA versus PA (MD = -0.33 days, 95%CI: − 0.55, − 0.11 days, P = 0.003), but there was no statistically significant difference between DAA and LA (MD = − 0.64 days, 95%CI: − 2.15, 0.88 days, P = 0.41) (Fig. 3b).

No statistical analysis could be performed for other peri-operative parameters due to heterogeneity of raw data. Four studies comparing DAA versus PA noted higher blood loss in DAA [19, 25, 27, 28], while seven studies comparing DAA versus LA did not report any significant difference [31, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41]. Several studies also reported significantly lower morphine equivalents required in DAA patients post-operatively [19, 24, 31, 36, 38], while others did not [25, 41]. Studies that evaluated transfusion rates [19, 27, 28, 36, 38, 41] and discharge destination [19, 41] did not notice any difference between DAA and other approaches.

Complications

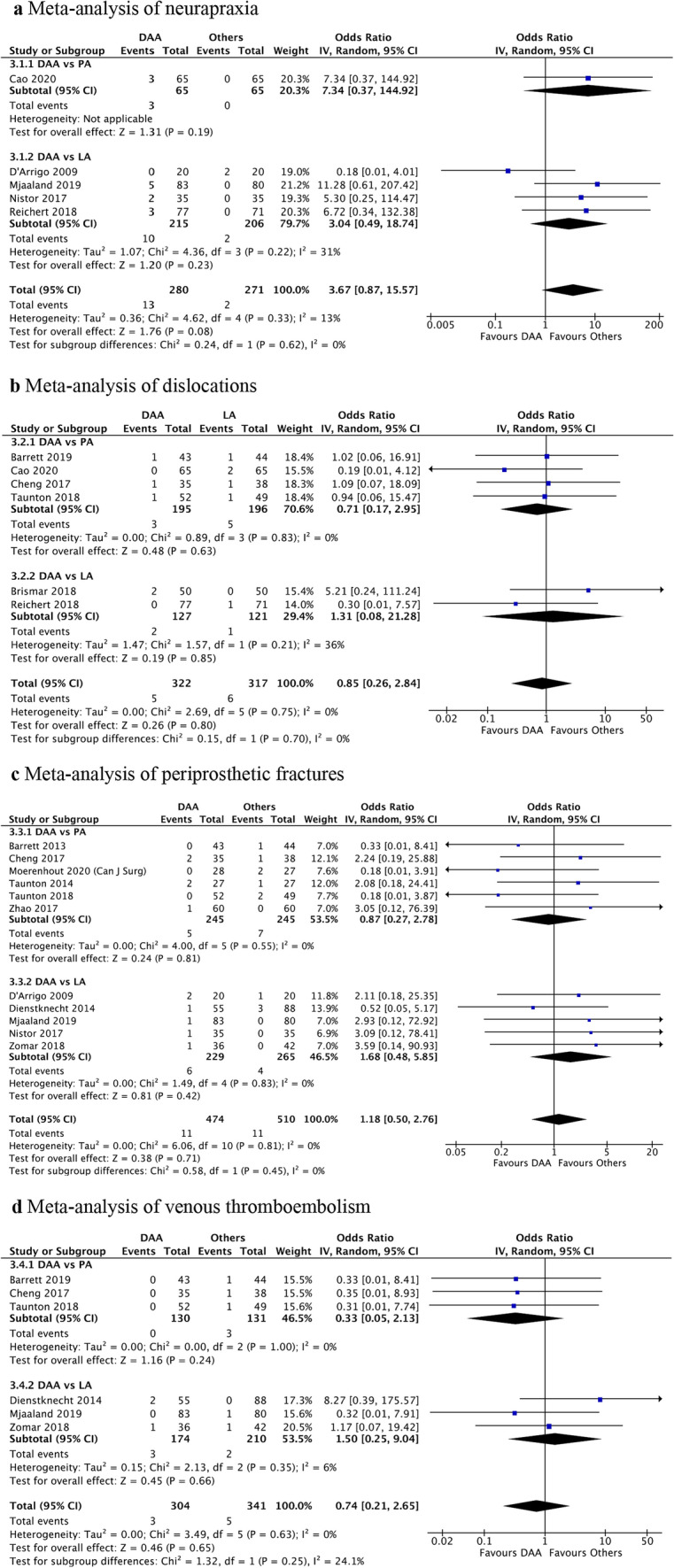

There was no significant difference in risk of neurapraxia between DAA and LA (OR = 3.04, 95%CI: 0.49, 18.74, P = 0.23). Meta-analysis for neurapraxia risk for DAA versus PA could not be performed as only Cao et al. reported neurapraxia rates [27] (Fig. 4a). Otherwise, there was no statistically significant difference in risk of dislocations, periprosthetic fractures or venous thromboembolisms when comparing DAA versus PA or LA (Figs. 4b–d).

Fig. 4.

a Meta-analysis of neurapraxia, b meta-analysis of dislocations, c meta-analysis of periprosthetic fractures, d meta-analysis of venous thromboembolism

Discussion

This is an updated comprehensive level-1 meta-analysis comparing functional outcomes, peri-operative parameters and complications of THA performed via DAA versus PA or LA. Most prominently, DAA had better functional outcomes in terms of HHS in the early post-operative period, with statistically significant difference at 6 weeks over PA and at 12 weeks over LA. While DAA had a slightly shorter mean length of stay than PA, DAA was associated with a significantly longer operative time than PA. There was no difference in risk of neurapraxia for DAA vs LA, and there was no difference in risks of dislocations, periprosthetic fractures or VTE between approaches.

An updated meta-analysis is justified due to increasing numbers of new RCTs published on this topic. The strict inclusion of only RCTs ensures that biases are minimised to produce the highest evidence level. While previous meta-analyses mainly compared two surgical approaches, our meta-analysis compared three main surgical approaches currently valid in clinical practice, with DAA being the common comparison. A network meta-analysis was not performed since assumptions associated with performing the analysis would reduce quality of evidence. Instead, our meta-analysis presents subgroup analysis comparing DAA with PA or LA and an overall analysis comparing DAA with PA and LA. This allows for direct comparison between DAA and other common approaches without compromising quality of evidence as with network meta-analysis.

DAA showed earlier recovery of function in the early post-operative period, which is consistent with previously published meta-analyses [5, 8, 11, 14, 17]. The quicker recovery has been attributed to the muscle-sparing nature of DAA by utilizing an inter-nervous plane between tensor fasciae latae and sartorius muscle superficially and between gluteus medius and rectus femoris deeper. Hence, muscle splitting is avoided and soft tissue injury is minimised [8, 43]. This is supported by biochemical and radiological evidence, with reports of lower levels of early post-operative creatine kinase or myoglobin, which are indicators of muscle damage, in DAA compared to other approaches [28, 34, 38, 39]. Post-operative MRI studies also noted less muscle and tendon damage in DAA than LA [34].

While no statistical analysis was performed for VAS pain scores, 8 of 11 RCTs reported lower levels of clinical pain measured by VAS in DAA versus other approaches. This could be attributed to minimal soft tissue trauma leading to earlier functional recovery. Pain is associated with poorer recovery following THA [44]. Progress of early post-operative rehabilitation is often limited and delayed due to pain; hence, lower pain VAS may be a positive driver and motivator of earlier rehabilitation. It should be noted that VAS pain levels and opioid requirements were only discussed qualitatively due to parameter heterogeneity. Post-operative analgesia regimes play a significant role in post-operative pain management, with the type of local anaesthetic used before skin closure, mode and type of analgesia used post-operatively greatly influencing VAS pain levels. Since analgesia regimes are not standardised across studies, it would be difficult to directly compare VAS pain without introducing bias.

HHS is a comprehensive instrument widely used to assess THA outcomes, comprising domains for pain severity, function, absence of deformity and range of motion. A study by Söderman et al. [45] concluded that HHS is a valid, reproducible and reliable indicator of clinical outcome after THA. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for HHS was reported to be 4 [46]. According to this measure, our results demonstrate a clinically significant improvement in HHS at 6 weeks for DAA versus PA but not at 12 weeks for DAA versus LA.

Previous meta-analyses comparing mean LoS in DAA versus PA have been inconsistent, with some reporting shorter LoS in DAA [5, 11], while others reporting no difference [8, 14]. Our study showed a slightly shorter LoS in DAA than PA, likely due to less soft tissue trauma in DAA and lower post-operative pain levels, which facilitates better tolerance and participation in early post-operative rehabilitation. Inconsistent results have also been reported for operative time between THA approaches, with some reporting increased operative time for DAA [11, 14], while others find no significant difference [5, 8]. This meta-analysis reports a longer operative time for DAA than PA postulated to be due to surgeon experience, the use of a fracture table and/or intraoperative fluoroscopy during DAA THA [25, 29]. Four RCTs noted higher blood loss for DAA versus PA. This could be attributed to the longer operative time for DAA over PA since blood loss has been noted to increase with surgical duration [47]. The long learning curve for DAA, which has previously been described, could be another contributing factor, though all but two [23, 28] of the RCTs comparing DAA versus PA involved surgeons experienced in DAA. While our results did not show any difference in peri-operative parameters between DAA and LA, Yue et al. [17] reported a longer operative time and shorter LoS for DAA compared to LA.

Overall, 14 of 24 RCTs involved surgeons experienced in DAA, [19–22, 24–27, 29, 30, 32, 35, 40, 42]. The remainder either involved surgeons still within the learning curve [28, 31, 33, 36–38, 41] or did not specify surgeon experience [23, 34, 39]. Complication risks during the learning curve of DAA can potentially be reduced with adequate supervision and guidance by experienced surgeons and by performing initial cases on less complex patients [48].

Although our study did not find an increased risk of neurapraxia for DAA vs LA and could not run the meta-analysis for DAA vs PA, previous meta-analyses have reported an increased risk of neurapraxia with DAA [11, 15, 16]. The LFCN is most often implicated in DAA as it lies within the intermuscular interval used for DAA with an incidence of 14.8–81% [49]. As a sensory nerve, the symptoms include numbness and neuropathic pain. LFCN injuries generally improve over time with several studies showing symptom improvement in over 88% of patients after 2 years [49]. On the other hand, the sciatic nerve is more likely to be implicated in the PA due to its posterior location. Although overall incidence of sciatic nerve injury is relatively low at 0.068–1.9% [49], the rate of full recovery is reportedly less than 50% [50]. Being a major motor nerve that supplies most of the posterior compartment musculature in the lower limb, an injury to the sciatic nerve can lead to debilitating functional consequences.

There was no significant difference in risk of dislocations, periprosthetic fractures or VTE between approaches, which is also consistent with previous meta-analysis [4, 8, 11, 15–17]. However, three meta-analyses did report a higher risk of dislocations in PA than DAA [4, 5, 15]. Medium-term data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) also reported an increased risk of revision surgery in PA THA indicated for recurrent dislocations (HR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.55, 2.20, p < 0.001). There are several reasons that could have led to this discrepancy in dislocation rates between our analysis and other reports. Firstly, including only RCTs meant that patient numbers are limited and there may be insufficient statistical power to demonstrate a significant difference. Furthermore, a majority of RCTs focused mainly on the early post-operative period which could be too early for all dislocations to occur. It was also noted that most PA THA included in this analysis was reported to have posterior capsule repair and/or peri-operative hip precautions to minimise the risk of dislocations. Other confounding factors for this discrepancy can be due to the higher numbers of PA for THA, differing indications for PA THA, differing soft tissue closure techniques and individual patient factors including soft tissue integrity and comorbidities.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this meta-analysis. Due to heterogeneity of reported PROMS and their follow-up intervals, only comparative analysis of HHS could be performed. PROMS that could not be quantitatively analysed are summarised in Appendix 1 for easy comparison between surgical approaches. The difference in surgeon experience amongst studies is a potential confounder given the learning curve of DAA of 100 procedures, with an increased risk of complications if this minimum threshold is not met [12, 13]. Although complication rates compared were consistently low across studies, the wide difference in follow-up duration across studies could have impacted the number and type of complications observed. Hence, it would be difficult to account for the impact that the learning curve has on complications in this context. Unfortunately, we could not control or adjust for the influence that this discrepancy could have had on our results. Several RCTs reported utilising minimally invasive surgery (MIS) techniques to perform THA. To date, the definition of MIS remains debatable [51, 52]. Traditionally, it is perceived that MIS involves smaller incisions. However, studies have shown that there are more factors to MIS than incision length alone, with minimal soft tissue trauma being a key principle [51, 52]. Hence, it would be exceptionally challenging to adjust for this factor given the lack of a standardised definition of MIS. Although osteoarthritis was the main indication for a majority of THAs performed, the inclusion of other diagnoses may act as confounding variables. Detection bias may have been introduced considering that discharge criteria and blinding of outcome assessors were not clearly defined in some RCTs [27, 29]. Lastly, the quality of RCTs included was limited by the inherent inability to completely blind participants and researchers given the nature of the intervention.

Conclusion

The DAA has better early functional outcomes with shorter mean length of stay and was associated with a longer operative time than PA. There was no difference in risk of neurapraxia for DAA vs LA, and there was no difference in risks of dislocations, periprosthetic fractures or VTE between approaches. Based on our results, preference of THA approach should ultimately be guided by surgeon experience, surgeon preference and patient factors.

Appendix 1

See Table 4.

Table 4.

Patient-reported outcome measures between approaches

| Articles | Year | No of patients | Outcome measure | Mean (Standard deviation) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAA vs PA | DAA | PA | DAA | PA | |||

| Barrett | 2013 | 43 | 44 | Pre-op VAS | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 0.1751 |

| 43 | 44 | Post-op immediate VAS | 4.2 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 0.2257 | ||

| 43 | 44 | Day 1 VAS | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 0.0472 | ||

| 43 | 44 | Day 2 VAS | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 0.2042 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week VAS | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 0.953 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month VAS | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 0.4414 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month VAS | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.4606 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year VAS | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.1857 | ||

| 43 | 44 | Pre-op HHS, pain | 17.3 ± 6.4 | 14.5 ± 5.0 | 0.0347 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HHS, pain | 39.8 ± 4.4 | 38.4 ± 5.4 | 0.2056 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HHS, pain | 37.5 ± 7.0 | 39.4 ± 6.2 | 0.2402 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HHS, pain | 41.1 ± 5.9 | 41.1 ± 5.7 | 0.9701 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HHS, pain | 42.0 ± 5.2 | 42.5 ± 4.4 | 0.6615 | ||

| 43 | 44 | Pre-op HHS, function | 22.2 ± 5.0 | 22.4 ± 4.8 | 0.8685 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HHS, function | 28.7 ± 3.7 | 25.5 ± 5.3 | 0.0027 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HHS, function | 31.5 ± 2.8 | 30.6 ± 3.5 | 0.2371 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HHS, function | 32.4 ± 1.4 | 32.6 ± 1.3 | 0.6626 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HHS, function | 32.8 ± 0.7 | 32.4 ± 1.6 | 0.1301 | ||

| 43 | 44 | Pre-op HHS, total | 57.6 ± 10.2 | 55.1 ± 9.1 | 0.2464 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HHS, total | 89.5 ± 8.1 | 81.4 ± 9.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HHS, total | 91.2 ± 9.7 | 91.4 ± 9.7 | 0.9317 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HHS, total | 95.8 ± 7.8 | 95.9 ± 6.8 | 0.968 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HHS, total | 97.5 ± 5.7 | 97.3 ± 5.5 | 0.87 | ||

| 43 | 44 | Pre-op 6MWT | 312.3 ± 80.7 | 291.1 ± 84.5 | 0.2379 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week 6MWT | 513.7 ± 750.5 | 344.4 ± 96.7 | 0.1644 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month 6MWT | 428.4 ± 95.2 | 402.3 ± 71.9 | 0.1842 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HOOS, symptoms | 79.4 ± 12.3 | 79.9 ± 11.6 | 0.8631 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HOOS, symptoms | 90 ± 11.5 | 83.9 ± 11.7 | 0.0471 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HOOS, symptoms | 90.6 ± 12.7 | 89.7 ± 8.9 | 0.7404 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HOOS, symptoms | 92.9 ± 13.2 | 92.1 ± 8.7 | 0.7574 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HOOS, pain | 83.5 ± 14.7 | 79.6 ± 16.7 | 0.2673 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HOOS, pain | 90.8 ± 11.6 | 89.0 ± 12.5 | 0.5214 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HOOS, pain | 90.7 ± 14.8 | 92.6 ± 9.6 | 0.5288 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HOOS, pain | 94.3 ± 12.7 | 93.4 ± 10.6 | 0.7407 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HOOS, ADL | 83.5 ± 13.7 | 79.0 ± 13.3 | 0.1341 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HOOS, ADL | 89.1 ± 12.1 | 89.7 ± 8.6 | 0.8122 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HOOS, ADL | 92.5 ± 12.7 | 93.3 ± 7.8 | 0.7521 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HOOS, ADL | 94.4 ± 11.2 | 95.4 ± 7.3 | 0.6518 | ||

| 42 | 44 | 6-week HOOS, QoL | 62.6 ± 19.8 | 54.7 ± 20.5 | 0.0777 | ||

| 35 | 38 | 3-month HOOS, QoL | 76.3 ± 18.2 | 67.5 ± 19.8 | 0.0606 | ||

| 34 | 36 | 6-month HOOS, QoL | 80.3 ± 20.2 | 82.3 ± 17.0 | 0.6615 | ||

| 34 | 41 | 1-year HOOS, QoL | 81.3 ± 21.8 | 85.3 ± 17.5 | 0.3769 | ||

| Barrett | 2019 | 41 | 44 | Pre-op UCLA | 3.68 ± 1.507 | 3.07 ± 0.873 | 0.026 |

| 36 | 39 | 5-year min UCLA | 6.33 ± 1.639 | 6.26 ± 1.888 | 0.8516 | ||

| 42 | 44 | Pre-op HHS | 56.7 ± 10.42 | 53.8 ± 10.19 | 0.1961 | ||

| 39 | 40 | 5-year min HHS | 96.9 ± 8.44 | 97.1 ± 9.95 | 0.9417 | ||

| 39 | 39 | 5-year min HOOS Jr | 95.7 ± 7.7 | 92.9 ± 14.1 | 0.2815 | ||

| Cao | 2020 | 65 | 65 | Pre-op HHS | 45.8 ± 4.0 | 46.8 ± 6.5 | 0.272 |

| 1-week HHS | 78.7 ± 3.3 | 71.7 ± 4.1 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 3-week HHS | 84.2 ± 3.4 | 77.2 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 6-week HHS | 88.7 ± 2.5 | 80.0 ± 2.6 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 3-month HHS | 91.6 ± 1.1 | 91.3 ± 1.3 | 0.1 | ||||

| 6-month HHS | 93.0 ± 1.5 | 92.9 ± 1.4 | 0.672 | ||||

| Pre-op VAS | 5.9 ± 1.3 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.085 | ||||

| 1-week VAS | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 3-week VAS | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 6-week VAS | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 3-month VAS | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.599 | ||||

| 6-month VAS | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.68 | ||||

| Cheng | 2017 | 35 | 38 | Pre-op WOMAC, pain | 13.1 ± 3.55 | 14.6 ± 3.51 | – |

| 35 | 38 | 2-week WOMAC, pain | 7.5 ± 4.20 | 7.5 ± 4.19 | 0.94 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week WOMAC, pain | 3.8 ± 3.31 | 3.7 ± 3.35 | 0.86 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week WOMAC, pain | 1.7 ± 2.72 | 2.3 ± 2.74 | 0.33 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op WOMAC, stiffness | 5.4 ± 1.72 | 6.1 ± 1.73 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week WOMAC, stiffness | 3.3 ± 1.95 | 3.6 ± 1.91 | 0.64 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week WOMAC, stiffness | 2.4 ± 1.66 | 2 ± 1.64 | 0.39 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week WOMAC, stiffness | 1.4 ± 1.66 | 1.8 ± 1.64 | 0.27 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op WOMAC, function | 44.5 ± 11 | 50.5 ± 10.97 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week WOMAC, function | 29.5 ± 12.78 | 33.4 ± 12.82 | 0.2 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week WOMAC, function | 13 ± 10.53 | 16.3 ± 10.46 | 0.2 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week WOMAC, function | 6 ± 8.28 | 8.7 ± 8.27 | 0.17 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op WOMAC, total | 63 ± 15.3 | 71.2 ± 15.29 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week WOMAC, total | 40.3 ± 17.81 | 44.5 ± 17.82 | 0.33 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week WOMAC, total | 19.2 ± 14.61 | 22 ± 14.6 | 0.43 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week WOMAC, total | 9.1 ± 12.13 | 12.8 ± 12.10 | 0.2 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op OHS | 19.1 ± 6.66 | 14.5 ± 6.66 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week OHS | 28.5 ± 9.23 | 26.8 ± 9.25 | 0.44 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week OHS | 39.8 ± 6.21 | 37.3 ± 6.14 | 0.1 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week OHS | 43.8 ± 5.15 | 42.8 ± 5.11 | 0.39 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op EQ5D | 0.4 ± 0.30 | 0.3 ± 0.31 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week EQ5D | 0.6 ± 0.24 | 0.5 ± 0.25 | 0.16 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week EQ5D | 0.8 ± 0.18 | 0.8 ± 0.18 | 0.86 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week EQ5D | 0.9 ± 0.12 | 0.9 ± 0.12 | 0.57 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op EQ5D VAS | 61.2 ± 19.4 | 59.1 ± 19.48 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week EQ5D VAS | 74 ± 15.97 | 74.1 ± 15.97 | 0.98 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week EQ5D VAS | 86.6 ± 9.64 | 87 ± 9.61 | 0.84 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week EQ5D VAS | 91.6 ± 7.75 | 91.9 ± 7.73 | 0.87 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op 10mWT normal (m/s) | 1.1 ± 0.24 | 1.1 ± 0.25 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week 10mWT normal (m/s) | 0.9 ± 0.24 | 0.8 ± 0.25 | 0.45 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week 10mWTnormal (m/s) | 1.2 ± 0.24 | 1.2 ± 0.24 | 0.55 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week 10mWT normal (m/s) | 1.3 ± 0.18 | 1.3 ± 0.18 | 0.85 | ||

| 35 | 38 | Pre-op 10mWT fast (m/s) | 1.5 ± 0.35 | 1.4 ± 0.37 | – | ||

| 35 | 38 | 2-week 10mWT fast (m/s) | 1.1 ± 0.30 | 1.1 ± 0.31 | 0.48 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 6-week 10mWT fast (m/s) | 1.6 ± 0.24 | 1.6 ± 0.24 | 0.9 | ||

| 35 | 37 | 12-week 10mWT fast (m/s) | 1.7 ± 0.24 | 1.7 ± 0.24 | 0.78 | ||

| Christensen | 2015 | 28 | 23 | Pre-op chair rising force | 48.8 ± 10.8 | 46.7 ± 8.0 | – |

| 6-week chair rising force | 53.2 ± 5.0 | 50.0 ± 4.8 | 0.7 | ||||

| Pre-op TUG | 10.3 ± 2.8 | 12.2 ± 4.4 | – | ||||

| 6-week TUG | 8.9 ± 2.5 | 10.0 ± 2.6 | 0.51 | ||||

|

Moerenhout (Can J Surg) |

2020 | 28 | 27 | Pre-op VAS | 5.0 ± 2.4 | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 0.029 |

| 28 | 27 | 2-week VAS | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 0.79 | ||

| 28 | 27 | 4-week VAS | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 0.63 | ||

| 28 | 27 | 3-month VAS | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 0.66 | ||

| 28 | 26 | 6-month VAS | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.61 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 1-year VAS | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.38 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 2-year VAS | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 1.9 | 1 | ||

| 28 | 27 | Pre-op HHS | 52.1 ± 19.7 | 48.2 ± 10.1 | 0.66 | ||

| 28 | 27 | 2-week HHS | 66.9 ± 17.1 | 60.0 ± 15.1 | 0.12 | ||

| 28 | 27 | 4-week HHS | 76.7 ± 16.4 | 68.7 ± 16.8 | 0.08 | ||

| 28 | 27 | 3-month HHS | 88.4 ± 11.8 | 83.3 ± 15.1 | 0.18 | ||

| 28 | 26 | 6-month HHS | 90.1 ± 11.3 | 90.3 ± 12.3 | 1 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 1-year HHS | 94.4 ± 8.0 | 91.4 ± 13.0 | 0.72 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 2-year HHS | 89.4 ± 11.9 | 88.7 ± 20.0 | 0.58 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 5-year HHS | 82.0 ± 19.8 | 80.0 ± 20.4 | 0.72 | ||

| Moerenhout (orthopaedics and traumatology) | 2021 | 24 | 21 | Pre-op MHHS | 41.7 | 34.4 | 0.6 |

| 5-year MHHS | 77.5 | 74.5 | 0.5 | ||||

| Rykov | 2017 | 23 | 23 | Pre-op HOOS | 33.4 ± 16.0 | 32.5 ± 13.5 | 0.87 |

| 20 | 18 | 6-week HOOS | 72.8 ± 16.9 | 71.0 ± 18.7 | 0.69 | ||

| 23 | 23 | Pre-op HHS | 52 ± 6.67 | 51 ± 8.95 | 0.85 | ||

| 20 | 18 | 6-week HHS | 93 ± 10.87 | 90 ± [9.14 | 0.36 | ||

| Taunton | 2014 | 27 | 27 | Pre-op SF12, mental | 56.95* | 55.73* | 0.488 |

| 3-week SF12, mental | 58.42* | 60.66* | 0.016 | ||||

| 6-week SF12, mental | 58.69* | 59.56* | 0.262 | ||||

| 1-year SF12, mental | 59.84* | 57.39* | 0.294 | ||||

| Pre-op SF12, physical | 30.28* | 34.59* | 0.26 | ||||

| 3-week SF12, physical | 44.33* | 43.45* | 0.406 | ||||

| 6-week SF12, physical | 53.57* | 53.64* | 0.4 | ||||

| 1-year SF12, physical | 53.80* | 53.19* | 0.389 | ||||

| Pre-op WOMAC, pain | 45.00* | 55.00* | 0.051 | ||||

| 3-week WOMAC, pain | 97.50* | 100.00* | 0.294 | ||||

| 6-week WOMAC, pain | 100.00* | 100.00* | 0.111 | ||||

| 1-year WOMAC, pain | 100.00* | 100.00* | 0.364 | ||||

| Pre-op WOMAC, stiffness | 37.50* | 50.00* | 0.105 | ||||

| 3-week WOMAC, stiffness | 75.00* | 75.00* | 0.101 | ||||

| 6-week WOMAC, stiffness | 87.50* | 87.50* | 0.41 | ||||

| 1-year WOMAC, stiffness | 87.50* | 87.50* | 0.346 | ||||

| Pre-op WOMAC, function | 50.00* | 48.53* | 0.478 | ||||

| 3-week WOMAC, function | 86.76* | 91.18* | 0.056 | ||||

| 6-week WOMAC, function | 97.06* | 97.06* | 0.392 | ||||

| 1-year WOMAC, function | 98.53* | 98.53* | 0.43 | ||||

| Pre-op WOMAC, total | 47.90* | 49.46* | 0.202 | ||||

| 3-week WOMAC, total | 87.20* | 91.49* | 0.043 | ||||

| 6-week WOMAC, total | 95.41* | 95.74* | 0.287 | ||||

| 1-year WOMAC, total | 97.38* | 97.38* | 0.492 | ||||

| Pre-op HHS, pain | 20* | 20* | 0.47 | ||||

| 3-week HHS, pain | 44* | 44* | 0.432 | ||||

| 6-week HHS, pain | 44* | 44* | 0.224 | ||||

| 1-year HHS, pain | 44* | 44/8 | 0.072 | ||||

| Pre-op HHS, function | 31* | 31* | 0.476 | ||||

| 3-week HHS, function | 37.5* | 32* | 0.08 | ||||

| 6-week HHS, function | 45* | 43* | 0.079 | ||||

| 1-year HHS, function | 45* | 44.5* | 0.166 | ||||

| Pre-op HHS, total | 55* | 51* | 0.497 | ||||

| 3-week HHS, total | 86.5* | 81* | 0.085 | ||||

| 6-week HHS, total | 97* | 93* | 0.135 | ||||

| 1-year HHS, total | 98* | 97.5* | 0.231 | ||||

| Taunton | 2018 | 52 | 49 | Post-op VAS | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | < 0.01 |

| Pre-op HHS | 57 ± 13 | 56 ± 12 | 0.69 | ||||

| 2-month HHS | 95 ± 6 | 92 ± 8 | 0.07 | ||||

| 1-year HHS | 97 ± 4 | 95 ± 7 | 0.44 | ||||

| Pre-op HOOS, symptoms | 20 ± 18 | 16 ± 16 | 0.35 | ||||

| 2-month HOOS, symptoms | 60 ± 12 | 57 ± 10 | 0.14 | ||||

| 1-year HOOS, symptoms | 69 ± 8 | 64 ± 13 | 0.05 | ||||

| Pre-op HOOS, pain | 16 ± 17 | 16 ± 12 | 0.98 | ||||

| 2-month HOOS, pain | 63 ± 12 | 61 ± 12 | 0.54 | ||||

| 1-year HOOS, pain | 69 ± 9 | 67 ± 11 | 0.41 | ||||

| Pre-op HOOS, ADLs | 20 ± 19 | 21 ± 15 | 0.79 | ||||

| 2-month HOOS, ADLs | 62 ± 11 | 61 ± 11 | 0.61 | ||||

| 1-year HOOS, ADLs | 69 ± 10 | 68 ± 10 | 0.42 | ||||

| Pre-op HOOS, sport/recreation | 3 ± 24 | 2 ± 19 | 0.95 | ||||

| 2-month HOOS, sport/recreation | 52 ± 20 | 51 ± 19 | 0.94 | ||||

| 1-year HOOS, sport/recreation | 63 ± 15 | 57 ± 17 | 0.1 | ||||

| Pre-op HOOS, QoL | -5 ± 16 | -1 ± 16 | 0.21 | ||||

| 2-month HOOS, QoL | 49 ± 19 | 45 ± 19 | 0.34 | ||||

| 1-year HOOS, QoL | 61 ± 18 | 56 ± 20 | 0.29 | ||||

| Pre-op SF 12, physical | 30 ± 7 | 31 ± 7 | 0.27 | ||||

| 2-month SF 12, physical | 45 ± 10 | 42 ± 8 | 0.12 | ||||

| 1-year SF 12, physical | 49 ± 10 | 50 ± 7 | 0.69 | ||||

| Pre-op SF 12, mental | 54 ± 10 | 53 ± 8 | 0.91 | ||||

| 2-month SF 12, mental | 54 ± 7 | 55 ± 7 | 0.65 | ||||

| 1-year SF 12, mental | 54 ± 7 | 54 ± 4 | 0.82 | ||||

| Pre-op steps/day | 6099 ± 3245 | 5144 ± 3189 | 0.23 | ||||

| 2-week steps/day | 3897 ± 2258 | 2235 ± 1688 | 0.04 | ||||

| 8-week steps/day | 6665 ± 3247 | 5503 ± 3523 | 0.23 | ||||

| 1-year steps/day | 6291 ± 3283 | 5857 ± 3160 | 0.62 | ||||

| Zhao | 2017 | 60 | 60 | Pre-op pain score | 6.12 ± 0.58 | 6.02 ± 0.43 | 0.18 |

| Pre-op VAS | 5.95 ± 0.46 | 5.92 ± 0.67 | 0.73 | ||||

| Day 1 VAS | 3.07 ± 0.84 | 3.79 ± 0.96 | 0.01 | ||||

| Day 2 VAS | 2.11 ± 0.28 | 3.09 ± 0.58 | 0.01 | ||||

| Day 3 VAS | 1.83 ± 0.43 | 2.49 ± 0.41 | 0.01 | ||||

| Pre-op HHS | 40.19 ± 9.23 | 43.11 ± 15.59 | 0.37 | ||||

| 3-month HHS | 85.9 ± 17.36 | 79.6 ± 11.87 | 0.04 | ||||

| 6-month HHS | 92.2 ± 13.25 | 89.9 ± 11.74 | 0.63 | ||||

| Pre-op UCLA | 4.03 ± 0.29 | 4.17 ± 0.26 | 0.22 | ||||

| 3-month UCLA | 5.37 ± 1.11 | 4.12 ± 1.23 | 0.03 | ||||

| 6-month UCLA | 7.04 ± 1.13 | 6.96 ± 1.21 | 0.67 | ||||

| DAA vs LA | DAA | LA | DAA | LA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D' Arrigo | 2009 | 20 | 20 | 6-week HHS | 93.1 ± 7.8 | 88.3 ± 8 | > 0.05 |

| 6-week WOMAC | 23.3 ± 9.9 | 27.7 ± 13.6 | 0.003 | ||||

| De Anta Diaz | 2016 | 50 | 49 | Pre-op HHS | 44.4 ± 13.6 | 42.9 ± 15.2 | 0.606 |

| 3-month HHS | 94.6 ± 10.2 | 92.8 ± 11.3 | 0.407 | ||||

| 12-month HHS | 96.2 ± 10.1 | 94.5 ± 9.7 | 0.397 | ||||

| Dienstknecht | 2014 | 55 | 88 | Pre-op HHS | 45.6 ± 15.9 | 45.6 ± 15.1 | 0.991 |

| 6-week HHS | 78.0 ± 12.7 | 74.1 ± 13.6 | 0.142 | ||||

| 3-month HHS | 87.1 ± 14.9 | 85.2 ± 16.5 | 0.562 | ||||

| Pre-op OHS | 20.0 ± 8.3 | 19.1 ± 8.0 | 0.508 | ||||

| 6-week OHS | 39.4 ± 7.0 | 37.0 ± 6.7 | 0.083 | ||||

| 3-month OHS | 41.9 ± 5.4 | 39.9 ± 8.7 | 0.196 | ||||

| Pre-op EQ-5D | 0.473 ± 0.235 | 0.466 ± 0.253 | 0.859 | ||||

| 6-week EQ-5D | 0.847 ± 0.167 | 0.810 ± 0.169 | 0.274 | ||||

| 3-month EQ-5D | 0.850 ± 0.216 | 0.845 ± 0.230 | 0.909 | ||||

| 6 h VAS | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 2.7 | 0.035 | ||||

| 12 h VAS | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 2.8 ± 2.7 | 0.02 | ||||

| Day 1 VAS | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 2.4 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Day 2 VAS | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 3.0 ± 2.1 | 0.007 | ||||

| Day 3 VAS | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 2.7 ± 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| Day 4 VAS | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 0.017 | ||||

| Day 5 VAS | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 0.011 | ||||

| Day 6 VAS | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 0.03 | ||||

| Day 7 VAS | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 0.06 | ||||

| Day 8 VAS | 1.4 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 0.056 | ||||

| Mjaaland | 2015 | 83 | 80 | Pre-op HHS | 53.6 ± 13.7 | 56.0 ± 11.2 | - |

| Pre-op OHS (0–48) | 25.2 ± 7.5 | 24.8 ± 6.8 | - | ||||

| Pre-op VAS (0–10) | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 5.7 ± 1.9 | - | ||||

| Day 1 VAS, before physiotherapy | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 4.0 ± 2.3 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Day 1 VAS, after physiotherapy | 3.0 ± 2.1 | 4.6 ± 2.2 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Day 2 VAS, before physiotherapy | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 0.001 | ||||

| Day 2 VAS, after physiotherapy | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Day 3 VAS, before physiotherapy | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Day 3 VAS, after physiotherapy | 1.9 ± 1.9 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Day 4 VAS, before physiotherapy | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 0.006 | ||||

| Day 4 VAS, after physiotherapy | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Mjaaland | 2019 | 83 | 80 | 3-month OHS | 39 ± 7 | 36 ± 7 | 0.02 |

| 12-month EQ-5D index | 0.83 ± 0.18 | 0.77 ± 0.20 | 0.04 | ||||

| Nistor | 2020 | 56 | 56 | After passive PT (day 1) VAS | 2* | 4* | < 0.001 |

| 56 | 56 | After active PT (day 2) VAS | 2* | 4* | < 0.001 | ||

| 56 | 56 | After active PT (day 3) VAS | 2* | 3* | < 0.001 | ||

| 56 | 56 | After active PT (day 4) VAS | 2* | 3* | < 0.001 | ||

| 54 | 55 | After 20mWT (6 week) VAS | 1* | 1* | 0.009 | ||

| 54 | 53 | After 20mWT (3 month) VAS | 0* | 1* | 0.062 | ||

| 48 | 47 | After 20mWT (6 month) VAS | 0* | 0* | 0.293 | ||

| 40 | 39 | After 20mWT (1 year) VAS | 0* | 0* | 0.424 | ||

| Reichert | 2018 | 77 | 71 | Pre-op HHS | 54.0 ± 14.2 | 53.0 ± 15.7 | 0.2813 |

| 76 | 53 | 6-week HHS | 81.6 ± 12.1 | 82.4 ± 12.0 | 0.068 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month HHS | 89.8 ± 9.3 | 88.4 ± 9.9 | 0.37 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month HHS | 90.3 ± 9.8 | 89.1 ± 10.0 | 0.556 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month HHS | 92.4 ± 8.6 | 91.4 ± 9.1 | 0.477 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op XSFMA, function | 35.2 ± 16.1 | 40.5 ± 16.0 | 0.053 | ||

| 76 | 53 | 6-week XSFMA, function | 21.2 ± 14.2 | 28.5 ± 15.9 | 0.026 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month XSFMA, function | 12.7 ± 12.5 | 18.8 ± 16.1 | 0.023 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month XSFMA, function | 11.6 ± 12.1 | 15.8 ± 15.4 | 0.094 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month XSFMA, function | 10.3 ± 13.0) | 15.1 ± 16.3 | 0.04 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op XSFMA, bother | 48.7 ± 20.5 | 53.0 ± 17.9 | 0.126 | ||

| 76 | 53 | 6-week XSFMA, bother | 26.6 ± 19.8 | 33.0 ± 18.3 | 0.055 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month XSFMA, bother | 19.8 ± 17.0 | 33.0 ± 18.1 | 0.099 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month XSFMA, bother | 16.8 ± 15.8 | 25.1 ± 17.9 | 0.149 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month XSFMA, bother | 15.8 ± 18.0 | 21.7 ± 19.6 | 0.056 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op SF36, physical | 27.4 ± 8.2 | 25.6 ± 8.7 | 0.152 | ||

| 76 | 53 | 6-week SF36, physical | 39.1 ± 9.7 | 34.8 ± 9.8 | 0.004 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month SF36, physical | 44.6 ± 9.2 | 40.7 ± 10 1 | 0.031 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month SF36, physical | 46.0 ± 10.0 | 42.7 ± 5.6 | 0.042 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month SF36, physical | 47.5 ± 9.9 | 42.9 ± 11.9 | 0.017 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op SF36, mental | 57.2 ± 8.5 | 56.3 ± 9.2 | 0.405 | ||

| 76 | 53 | 6-week SF36, mental | 58.1 ± 8.7 | 59.3 ± 66 | 0.465 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month SF36, mental | 56.0 ± 9.2 | 56.7 ± 8.3 | 0.774 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month SF36, mental | 56.0 ± 10.0 | 55.8 ± 72 | 0.67 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month SF36, mental | 55.0 ± 9.8 | 56.2 ± 6.9 | 0.714 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op Stepwatch Activity Monitor | 4695 | 4695 | - | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month Stepwatch Activity Monitor | 5992 | 5239 | 0.035 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month Stepwatch Activity Monitor | 6402 | 5340 | 0.012 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op T25-FW (s) | 22.4 ± 5.2 | 24.0 ± 3.9 | 0.193 | ||

| 76 | 53 | 6-week T25-FW (s) | 21.3 ± 6.3 | 22.0 ± 4.2 | 0.385 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month T25-FW (s) | 18.5 ± 3.7 | 19.4 ± 3.8 | 0.291 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month T25-FW (s) | 18.3 ± 4.1 | 19.9 ± 5.5 | 0.04 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month T25-FW (s) | 18.1 ± 3.4 | 19.8 ± 4.6 | 0.046 | ||

| 77 | 71 | Pre-op activity VAS | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 0.461 | ||

| 76 | 53 | 6-week activity VAS | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 0.031 | ||

| 75 | 53 | 3-month activity VAS | 7.3 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 0.08 | ||

| 75 | 50 | 6-month activity VAS | 7.3 ± 0.7 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 0.223 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month activity VAS | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 | ||

| 73 | 50 | 12-month walking distance (m) | 6435 ± 4260 | 5125 ± 3868 | 0.045 | ||

| Restrepo | 2010 | 50 | 50 | Pre-op HHS | 51.86 | 54.95 | 0.06 |

| 6-week HHS | 93.64 | 88.8 | 0.03 | ||||

| 6-month HHS | 94.45 | 90.03 | 0 | ||||

| 1-year HHS | 94.72 | 92.08 | 0.04 | ||||

| 2-year HHS | 97.34 | 97.55 | 0.72 | ||||

| Pre-op LEFS | 6.72 | 6.51 | 0.25 | ||||

| 6-week LEFS | 10.36 | 9.9 | 0.36 | ||||

| 6-month LEFS | 10.12 | 9.56 | 0.04 | ||||

| 1-year LEFS | 10.3 | 10.12 | 0.5 | ||||

| 2-year LEFS | 10.58 | 10.14 | 0.07 | ||||

| Pre-op WOMAC | 8.68 | 8.33 | 0.29 | ||||

| 6-week WOMAC | 4.4 | 9.7 | 0 | ||||

| 6-month WOMAC | 3.46 | 8.62 | 0 | ||||

| 1-year WOMAC | 3.68 | 6.06 | 0.02 | ||||

| 2-year WOMAC | 2.24 | 1.9 | 0.6 | ||||

| Pre-op Linear Analogue Scale, Energy | 5.89 | 5.72 | 39 | ||||

| 6-week Linear Analogue Scale, Energy | 7.71 | 7.15 | 0.06 | ||||

| 6-month Linear Analogue Scale, Energy | 7.82 | 7.29 | 0.06 | ||||

| 1-year Linear Analogue Scale, Energy | 7.9 | 7.43 | 0.11 | ||||

| 2-year Linear Analogue Scale, Energy | 7.96 | 7.91 | 0.63 | ||||

| Pre-op Linear Analogue Scale, Daily Activity | 6.6 | 6.46 | 0.36 | ||||

| 6-week Linear Analogue Scale, Daily Activity | 8.13 | 7.48 | 0.49 | ||||

| 6-month Linear Analogue Scale, Daily Activity | 8.29 | 7.84 | 0.19 | ||||

| 1-year Linear Analogue Scale, Daily Activity | 8.35 | 7.91 | 0.19 | ||||

| 2-year Linear Analogue Scale, Daily Activity | 8.08 | 8.14 | 0.57 | ||||

| Pre-op Linear Analogue Scale, Overall | 6.07 | 5.93 | 0.57 | ||||

| 6-week Linear Analogue Scale, Overall | 8.23 | 7.33 | 0 | ||||

| 6-month Linear Analogue Scale, Overall | 8.54 | 7.75 | 0.02 | ||||

| 1-year Linear Analogue Scale, Overall | 8.59 | 7.79 | 0.01 | ||||

| 2-year Linear Analogue Scale, Overall | 8.23 | 8.26 | 0.88 | ||||

| Pre-op SF36, Physical | 68.91 | 66.32 | 0.27 | ||||

| 6-week SF36, Physical | 87.74 | 70.35 | 0 | ||||

| 6-month SF36, Physical | 89.02 | 75.14 | 0 | ||||

| 1-year SF36, Physical | 89.22 | 84.78 | 0.13 | ||||

| 2-year SF36, Physical | 90.44 | 91.11 | 0.6 | ||||

| Pre-op SF36, Mental | 26.86 | 28.98 | 0.57 | ||||

| 6-week SF36, Mental | 89.7 | 81.3 | 0 | ||||

| 6-month SF36, Mental | 90.64 | 79.72 | 0 | ||||

| 1-year SF36, Mental | 90.16 | 86.85 | 0.18 | ||||

| 2-year SF36, Mental | 92.51 | 92.9 | 0.58 | ||||

| Zomar | 2018 | 36 | 42 | Pre-op WOMAC, pain | 48.89 ± 15.9 | 44.02 ± 16.85 | 0.2 |

| 36 | 41 | 6-week WOMAC, pain | 73.21 ± 14.22 | 76.65 ± 14.02 | 0.29 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week WOMAC, pain | 83.65 ± 12.47 | 89.16 ± 12.33 | 0.06 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op WOMAC, stiffness | 43.40 ± 20.58 | 42.99 ± 17.24 | 0.92 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 6-week WOMAC, stiffness | 64.27 ± 16.56 | 69.22 ± 16.39 | 0.19 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week WOMAC, stiffness | 74.67 ± 14.99 | 73.97 ± 14.86 | 0.84 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op WOMAC, function | 47.10 ± 16.56 | 42.50 ± 13.67 | 0.18 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 6-week WOMAC, function | 73.44 ± 14.7 | 74.72 ± 14.54 | 0.71 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week WOMAC, function | 82.48 ± 12.64 | 84.82 ± 12.52 | 0.43 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op WOMAC, total | 47.07 ± 16.32 | 43.24 ± 12.83 | 0.27 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 6-week WOMAC, total | 71.50 ± 13.26 | 74.30 ± 13.06 | 0.36 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week WOMAC, total | 81.34 ± 11.60 | 84.35 ± 11.5 | 0.27 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op SF12, physical | 33.19 ± 9.72 | 31.04 ± 6.93 | 0.26 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 2-week SF12, physical | 31.05 ± 7.8 | 30.37 ± 7.75 | 0.71 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 6-week SF12, physical | 40.65 ± 9.24 | 40.68 ± 9.16 | 0.99 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week SF12, physical | 45.92 ± 8.21 | 46.67 ± 8.10 | 0.7 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op SF12, mental | 55.57 ± 12 | 51.43 ± 11.21 | 0.12 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 2-week SF12, mental | 52.52 ± 10.14 | 54.09 ± 9.99 | 0.5 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 6-week SF12, mental | 52.80 ± 9.54 | 54.07 ± 9.41 | 0.56 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week SF12, mental | 55.16 ± 8.10 | 55.81 ± 7.97 | 0.73 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op HHS | 63.16 ± 8.34 | 58.04 ± 11.99 | 0.04 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week HHS | 95.44 ± 7.18 | 92.04 ± 7.08 | 0.05 | ||

| 36 | 42 | Pre-op VAS | 5.32 ± 2.4 | 6.24 ± 1.75 | 0.06 | ||

| 36 | 41 | DC VAS | 4.17 ± 2.64 | 3.86 ± 2.50 | 0.66 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 2-week VAS | 2.76 ± 2.28 | 2.74 ± 2.24 | 0.98 | ||

| 36 | 41 | 6-week VAS | 1.57 ± 1.92 | 1.04 ± 1.86 | 0.23 | ||

| 33 | 40 | 12-week VAS | 0.85 ± 1.67 | 0.60 ± 1.64 | 0.52 |

HHS Harris Hip Score, MHHS : Modified Harris Hip Score, OHS :Oxford Hip Score, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index Score, EQ-5D EuroQoL 5-Dimension, HOOS Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, VAS Visual Analogue Scale, SF12 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, SF36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, UCLA University of California Los Angeles activity scores, LEFS Lower Extremity Functional Scale, TUG timed up and go, XSFMA extra short musculoskeletal functional assessment, mWT meter walk test, MWT minute walk test, T25-FW timed 25-m foot walk. *median values presented. Bolded p-values are meant to highlight statistical significance

Authors’ contribution

First author and second author helped in conception and design, collection and assembly of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of article, critical revision of article, final approval of article.

Third author and supervising author contributed to conception and design, critical revision of article, final approval of article.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

James Jia Ming Ang, Email: james_angjiaming@hotmail.com.

James Randolph Onggo, Email: jamesonggo1993@hotmail.com.

Christopher Michael Stokes, Email: Christopher.m.stokes@gmail.com.

Anuruban Ambikaipalan, Email: rubanambi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ackerman IN, Bohensky MA, Zomer E, Tacey M, Gorelik A, Brand CA, de Steiger R. The projected burden of primary total knee and hip replacement for osteoarthritis in Australia to the year 2030. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):90–90. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2411-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shan L, Shan B, Graham D, Saxena A. Total hip replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis on mid-term quality of life. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(3):389–406. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talia AJ, Coetzee C, Tirosh O, Tran P. Comparison of outcome measures and complication rates following three different approaches for primary total hip arthroplasty: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2368-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docter S, Philpott HT, Godkin L, Bryant D, Somerville L, Jennings M, Marsh J, Lanting B. Comparison of intra and post-operative complication rates among surgical approaches in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop. 2020;20:310–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins BT, Barlow DR, Heagerty NE, Lin TJ. Anterior vs. posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplast. 2015;30(3):419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon MS, Kuskowski M, Mulhall KJ, Macaulay W, Brown TE, Saleh KJ. Does surgical approach affect total hip arthroplasty dislocation rates? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:34–38. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000218746.84494.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen CP, Karthikeyan T, Jacobs CA. Greater prevalence of wound complications requiring reoperation with direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(9):1839–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Hou J-z, Wu C-h, Zhou Y-j, Gu X-m, Wang H-h, Feng W, Cheng Y-x, Sheng X, Bao H-w. A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct anterior approach versus posterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-0929-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheth D, Cafri G, Inacio MCS, Paxton EW, Namba RS. Anterior and anterolateral approaches for THA are associated with lower dislocation risk without higher revision risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(11):3401–3408. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4230-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton C, Kim PR. Complications of the direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(3):371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia F, Guo B, Xu F, Hou Y, Tang X, Huang L. A comparison of clinical, radiographic and surgical outcomes of total hip arthroplasty between direct anterior and posterior approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hip Int. 2018;29(6):584–596. doi: 10.1177/1120700018820652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari M, Matta JM, Dodgin D, Clark C, Kregor P, Bradley G, Little L. Outcomes following the single-incision anterior approach to total hip arthroplasty: a multicenter observational study. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(3):329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartford JM, Bellino MJ. The learning curve for the direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: a single surgeon's first 500 cases. Hip Int. 2017;27(5):483–488. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meermans G, Konan S, Das R, Volpin A, Haddad FS. The direct anterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2017;99B(6):732–740. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B6.38053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller LE, Gondusky JS, Kamath AF, Boettner F, Wright J, Bhattacharyya S. Influence of surgical approach on complication risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2018;89(3):289–294. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2018.1438694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X-t, Huang H-f, Sun L, Yang Z, Deng C-y, Tian X-b. Direct anterior approach versus posterolateral approach in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Orthop Surg. 2020;12(4):1065–1073. doi: 10.1111/os.12669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue C, Kang P, Pei F. Comparison of direct anterior and lateral approaches in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) Medicine. 2015;94(50):e2126–e2126. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng TE, Wallis JA, Taylor NF, Holden CT, Marks P, Smith CL, Armstrong MS, Singh PJ. A prospective randomized clinical trial in total hip arthroplasty-comparing early results between the direct anterior approach and the posterior approach. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(3):883–890. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen CP, Jacobs CA. Comparison of patient function during the first six weeks after direct anterior or posterior total hip arthroplasty (THA): a randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moerenhout K, Benoit B, Gaspard HS, Rouleau DM, Laflamme GY. Greater trochanteric pain after primary total hip replacement, comparing the anterior and posterior approach: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107(8):102709. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moerenhout K, Derome P, Laflamme GY, Leduc S, Gaspard HS, Benoit B. Direct anterior versus posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: a multicentre, prospective, randomized clinical trial. Can J Surg. 2020;63(5):E412–e417. doi: 10.1503/cjs.012019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taunton MJ, Mason JB, Odum SM, Springer BD. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty yields more rapid voluntary cessation of all walking aids: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9 Suppl):169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taunton MJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ, Kaufman K, Pagnano MW. John charnley award: randomized clinical trial of direct anterior and miniposterior approach THA: which provides better functional recovery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(2):216–229. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett WP, Turner SE, Leopold JP. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1634–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett WP, Turner SE, Murphy JA, Flener JL, Alton TB. Prospective, randomized study of direct anterior approach vs posterolateral approach total hip arthroplasty: a concise 5-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(6):1139–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao J, Zhou Y, Xin W, Zhu J, Chen Y, Wang B, Qian Q. Natural outcome of hemoglobin and functional recovery after the direct anterior versus the posterolateral approach for total hip arthroplasty: a randomized study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01716-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao HY, Kang PD, Xia YY, Shi XJ, Nie Y, Pei FX. Comparison of early functional recovery after total hip arthroplasty using a direct anterior or posterolateral approach: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(11):3421–3428. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rykov K, Reininga IHF, Sietsma MS, Knobben BAS, Ten Have B. Posterolateral vs direct anterior approach in total hip arthroplasty (POLADA trial): a randomized controlled trial to assess differences in serum markers. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(12):3652–3658.e3651. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reininga IH, Stevens M, Wagenmakers R, Boerboom AL, Groothoff JW, Bulstra SK, Zijlstra W. Comparison of gait in patients following a computer-navigated minimally invasive anterior approach and a conventional posterolateral approach for total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(2):288–294. doi: 10.1002/jor.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brismar BH, Hallert O, Tedhamre A, Lindgren JU. Early gain in pain reduction and hip function, but more complications following the direct anterior minimally invasive approach for total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial of 100 patients with 5 years of follow up. Acta Orthop. 2018;89(5):484–489. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2018.1504505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brun OCL, Sund HN, Nordsletten L, Rohrl SM, Mjaaland KE. Component placement in direct lateral vs minimally invasive anterior approach in total hip arthroplasty: radiographic outcomes from a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1718–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Arrigo C, Speranza A, Monaco E, Carcangiu A, Ferretti A. Learning curve in tissue sparing total hip replacement: comparison between different approaches. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(1):47–54. doi: 10.1007/s10195-008-0043-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Anta-Diaz B, Serralta-Gomis J, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Benavidez E, Lopez-Prats FA. No differences between direct anterior and lateral approach for primary total hip arthroplasty related to muscle damage or functional outcome. Int Orthop. 2016;40(10):2025–2030. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-3108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dienstknecht T, Luring C, Tingart M, Grifka J, Sendtner E. Total hip arthroplasty through the mini-incision (Micro-hip) approach versus the standard transgluteal (Bauer) approach: a prospective, randomised study. J Orthop Surg. 2014;22(2):168–172. doi: 10.1177/230949901402200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mjaaland KE, Kivle K, Svenningsen S, Pripp AH, Nordsletten L. Comparison of markers for muscle damage, inflammation, and pain using minimally invasive direct anterior versus direct lateral approach in total hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(9):1305–1310. doi: 10.1002/jor.22911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mjaaland KE, Kivle K, Svenningsen S, Nordsletten L. Do postoperative results differ in a randomized trial between a direct anterior and a direct lateral approach in THA? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(1):145–155. doi: 10.1097/corr.0000000000000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nistor DV, Caterev S, Bolboaca SD, Cosma D, Lucaciu DOG, Todor A. Transitioning to the direct anterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. Is it a true muscle sparing approach when performed by a low volume hip replacement surgeon? Int Orthop. 2017;41(11):2245–2252. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nistor DV, Bota NC, Caterev S, Todor A. Are physical therapy pain levels affected by surgical approach in total hip arthroplasty? A randomized controlled trial. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2020;12(1):8399. doi: 10.4081/or.2020.8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichert JC, von Rottkay E, Roth F, Renz T, Hausmann J, Kranz J, Rackwitz L, Noth U, Rudert M. A prospective randomized comparison of the minimally invasive direct anterior and the transgluteal approach for primary total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Pour AE, Hozack WJ. Prospective randomized study of two surgical approaches for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(5):671–679.e671. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zomar BO, Bryant D, Hunter S, Howard JL, Vasarhelyi EM, Lanting BA. A randomised trial comparing spatio-temporal gait parameters after total hip arthroplasty between the direct anterior and direct lateral surgical approaches. Hip Int. 2018;28(5):478–484. doi: 10.1177/1120700018760262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin CT, Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Clark CR. A comparison of hospital length of stay and short-term morbidity between the anterior and the posterior approaches to total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(5):849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satterly T, Neeley R, Johnson-Wo AK, Bhowmik-Stoker M, Shrader MW, Jacofsky MC, Jacofsky DJ. Role of total knee arthroplasty approaches in gait recovery through 6 months. J Knee Surg. 2013;26(4):257–262. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Söderman P, Malchau H. Is the harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res ®. 2001;384:189–197. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200103000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoeksma HL, Van Den Ende CHM, Ronday HK, Heering A, Breedveld FC. Comparison of the responsiveness of the harris hip Score with generic measures for hip function in osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(10):935–938. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.10.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross D, Erkocak O, Rasouli MR, Parvizi J. Operative time directly correlates with blood loss and need for blood transfusion in total joint arthroplasty. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2019;7(3):229–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters RM, Ten Have B, Rykov K, Van Steenbergen L, Putter H, Rutgers M, Vos S, Van Steijnen B, Poolman RW, Vehmeijer SBW, Zijlstra WP. The learning curve of the direct anterior approach is 100 cases: an analysis based on 15,875 total hip arthroplasties in the dutch arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop. 2022;93:775–782. doi: 10.2340/17453674.2022.4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel NK, Krumme J, Golladay GJ. Incidence, injury mechanisms, and recovery of iatrogenic nerve injuries during hip and knee arthroplasty. JAAOS J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(19):e940–e949. doi: 10.5435/jaaos-d-21-00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasija R, Kelly JJ, Shah NV, Newman JM, Chan JJ, Robinson J, Maheshwari AV. Nerve injuries associated with total hip arthroplasty. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(1):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siddiqui NA, Mohandas P, Muirhead-Allwood S, Nuthall T. (i) A review of minimally invasive hip replacement surgery—current practice and the way forward. Curr Orthop. 2005;19(4):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cuor.2005.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldstein WM, Branson JJ, Berland KA, Gordon AC. Minimal-incision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85A(Suppl 4):33–38. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300004-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]