Abstract

Purpose

Deep learning (DL) has been widely used in various medical imaging analyses. Because of the difficulty in processing volume data, it is difficult to train a DL model as an end-to-end approach using PET volume as an input for various purposes including diagnostic classification. We suggest an approach employing two maximum intensity projection (MIP) images generated by whole-body FDG PET volume to employ pre-trained models based on 2-D images.

Methods

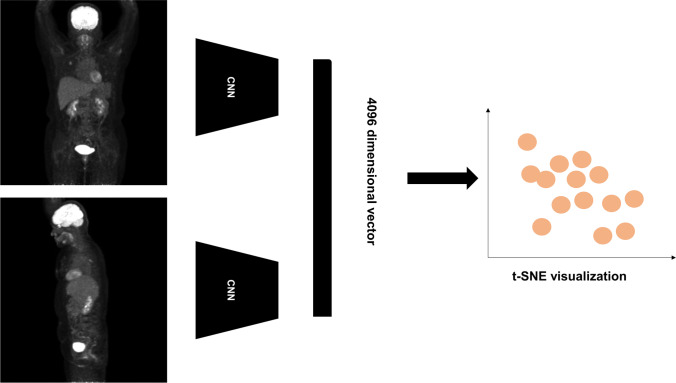

As a retrospective, proof-of-concept study, 562 [18F]FDG PET/CT images and clinicopathological factors of lung cancer patients were collected. MIP images of anterior and lateral views were used as inputs, and image features were extracted by a pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) model, ResNet-50. The relationship between the images was depicted on a parametric 2-D axes map using t-distributed stochastic neighborhood embedding (t-SNE), with clinicopathological factors.

Results

A DL-based feature map extracted by two MIP images was embedded by t-SNE. According to the visualization of the t-SNE map, PET images were clustered by clinicopathological features. The representative difference between the clusters of PET patterns according to the posture of a patient was visually identified. This map showed a pattern of clustering according to various clinicopathological factors including sex as well as tumor staging.

Conclusion

A 2-D image-based pre-trained model could extract image patterns of whole-body FDG PET volume by using anterior and lateral views of MIP images bypassing the direct use of 3-D PET volume that requires large datasets and resources. We suggest that this approach could be implemented as a backbone model for various applications for whole-body PET image analyses.

Keywords: Deep learning, PET/CT, Maximum intensity projection, Convolutional neural network, FDG

Introduction

Deep learning (DL) using the convolutional neural network (CNN) model is being applied to various medical imaging analyses. Analysis such as anatomical segmentation, lesion detection, and localization is being attempted in many other images such as plain radiography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and mammography [1, 2]. A DL model is also used in positron emission tomography (PET) image analysis [3]. For example, in brain PET using various radiotracers, DL-based image evaluation can create an image-based classification or quantitative biomarker by finding new patterns and can aid the diagnosis of neurologic disease [4–6]. Whole-body PET can be used to differentiate a tumor from a benign lesion and to predict prognosis by obtaining the total metabolic tumor volume [7–9]. PET using various radiotracers will highly likely be more utilized in various diseases.

When compared to other images, a 3-dimensional (3-D) volume of PET images presents difficulties in training an end-to-end model. It is possible to develop a model that meets the purpose by fine-tuning it if there is a pre-trained model obtained from a very large dataset. Many medical imaging studies using DL models have used pre-trained CNN models such as Inception, VGG, and ResNet, as these models could extract discriminative image features without training even though fine-tuning with real data is required [10]. Thus, the direct use of PET volume as an input has drawbacks in the lack of a pre-trained model as well as memory issues as a practical difficulty in research. For this reason, a DL model directly using whole-body PET volume has not yet been widely applied to image classification or prediction for clinical outcomes [3, 9].

To overcome these issues, we suggest an approach to extract features of whole-body PET images employing maximum intensity projection images with a 2-D image-based pre-trained CNN model. Instead of using whole-body PET volume, only images of anterior and lateral views of the MIP images could extract discriminative patterns of PET volumes. As a proof-of-concept study, we visualized these features using a t-distributed stochastic neighborhood embedding (t-SNE) map. We expected our approach using DL-based feature extraction from MIP images could be used as a backbone model of various DL-based PET image analyses.

Materials and Methods

Patients

In this study, 562 lung cancer patients who underwent [18F]FDG PET/CT as baseline evaluation from January 2018 to December 2018 in our institution were analyzed. We collected various clinicopathological factors, such as tumor size (long diameter measured on CT image), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation, and pathologic M stage. Clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of enrolled patients

| Clinicopathological factors | Number of patients (total n = 526) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.5 ± 10.3 [min–max: 30–91] |

| Sex | |

| F | 215 |

| M | 347 |

| Tumor size (cm) | n = 280 |

| ≤ 2.5 | 145 (51.8%) |

| 2.5 < ≤ 5.0 | 104 (37.1%) |

| 5.0 < ≤ 7.5 | 23 (8.2%) |

| 7.5 < ≤ 10.0 | 6 (2.1%) |

| 10.0 < ≤ 12.5 | 1 (0.4%) |

| ≥12.5 | 1 (0.4%) |

| EGFR mutation | n = 336 |

| Y | 155 (46.1%) |

| N | 181 (53.9%) |

| Pathologic M stage | n = 396 |

| M0 | 265 (66.9%) |

| M1a | 34 (8.6%) |

| M1b | 9 (2.3%) |

| M1c | 88 (22.2%) |

[18F]FDG PET/CT

All patients fasted for at least 8 h before [18F]FDG injection. Blood glucose level was checked before the radiotracer injection. Patients received 5.18 MBq/Kg of [18F]FDG when their blood glucose level was less than 200 mg/dL. After voiding, PET/CT scan was performed 60 min after [18F]FDG injection. PET scans were acquired using dedicated PET/CT scanners (Biograph mCT40 or mCT64, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). First, CT scanning was performed without contrast enhancement from the cranial base to the proximal thigh. Then PET emission scans were examined for 1 min per bed position. Attenuation-corrected PET images were reconstructed by an iterative algorithm (ordered subset expectation maximization, 2 iterations, 21 subsets, 5-mm Gaussian filter).

Generation of MIP Images

Whole-body PET images were resliced to a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. MIP images of the anterior and lateral views were generated from 3-D matrices of PET volume. Each pixel value of the MIP images represented a standardized uptake value (SUV). Each pixel value of the MIP image was clipped to set the range of SUVmax from 0 to 10 for visual pattern analysis and then scaled to the 0 to 255 range. This process was performed to use a pre-trained CNN model, ResNet-50. Because of the difference in the number of bed positioning, MIP images have different matrix sizes. Thus, two MIP images were changed to square matrices (600 × 600) by zero padding. Lastly, the images were modified to a size of 224 × 224 to be input into the ResNet-50 model [11].

Feature Extraction and Embedding

We applied the ResNet-50 model [12] for extracting features of MIP images. All processes were performed with the TensorFlow package (version 2.4.1) [13]. Using the ResNet-50 model, 2048 dimensional vectors were extracted from the MIP images of two views, respectively. The 2048 dimensional vectors were the last layer of ResNet-50 before the 1000 classification label for ImageNet. Because we used a pair of MIP images, the last layer was simply concatenated to extract features to be 4096 dimensional vectors. These features were regarded as discriminative features of PET volumes of subjects.

For visualizing the relationship of extracted features according to the similarities, we employed a t-SNE model [14]. Four thousand ninety-six features of each PET volume were used as input for the t-SNE model. t-SNE embedding was performed by the scikit-learn package (ver 0.24.1). Additionally, clinical factors were applied to the t-SNE map as color codes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scheme of image processing, feature extraction, and t-distributed stochastic neighborhood embedding (t-SNE) visualization. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) images of anterior and lateral views are generated and input to the deep learning (DL) model. Four thousand ninety-six vectors extracted from each image were visualized using a t-SNE map

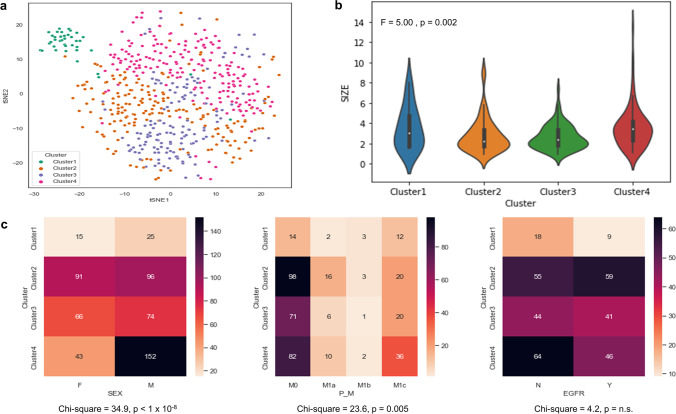

The 4096 features extracted by our suggested model were used for the clustering. K-means clustering was performed using 4096 features across 562 image data. The optimal value of k (the number of clusters, k=4) was determined by the elbow method by calculating a sum of squared distances to each center of a cluster. To evaluate the association between the clusters defined by the DL model and clinical variables, the chi-square test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively.

Results

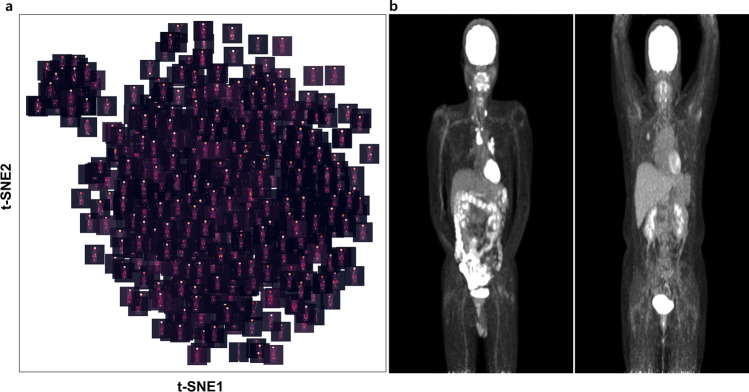

Visual Patterns of FDG PET Images Projection to t-SNE Map

FDG PET image features of all patients were extracted by the DL model. Those features were projected to 2-D axes using t-SNE. Each point indicates individual PET data. The association of points indicated the local similarity of features extracted by the model. Accordingly, a t-SNE map shows some grouped images having similarities. The t-SNE map visually showed two groups, one with a small number of images located on the left upper portion of the t-SNE map and the other with a large number of images (Fig. 2a). Figure 2b depicted representative images of each group. The difference between the two images was whether the arms were raised or not. This embedding could identify abnormal data, for example, at the bottom of the map, there was an upside-down image, and at the top right of the map, there was an image showing urine activity of Foley’s catheter.

Fig. 2.

Visualization of anterior MIP image features on t-SNE map. (a) Two clusters of different numbers of positron emission tomography (PET) images are shown. (b) Two representative images of each cluster are shown. These are anterior MIP images of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET taken with arms lowered and with arms raised

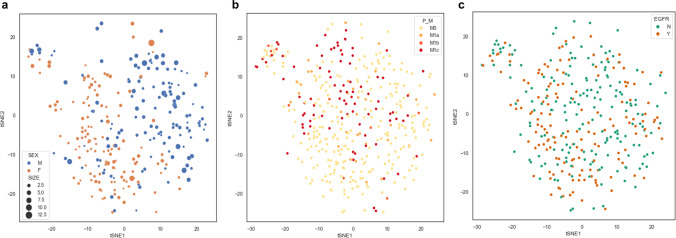

Embedding Clinicopathological Factors to t-SNE Map

We embedded the aforementioned clinicopathological factors together on the t-SNE map (Fig. 3). Additionally, we performed K-mean clustering, and we analyzed an association between clinicopathological factors and each cluster. The result is shown in the Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

t-SNE map embedded with clinicopathological factors. Each dot represents a PET image of each patient. Two groups according to sex are clustered. The size of each dot indicates tumor size representing long axis of the tumor measured on CT images (a). The pathologic M stage (b) and the presence of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation (c) are represented at each dot. (P_M = pathologic M stage, Y: presence of EGFR mutation, N: absence of EGFR mutation)

Fig. 4.

Results of K-means clustering and association analysis. (a) The t-SNE map shows 4 clusters. (b) The distribution of tumor size of each cluster and the result of the one-way ANOVA test are shown. (c) Each heatmap and result of the Chi-square test shows the association between clinicopathological factors and each cluster

The group was well defined according to sex and tumor size (Fig. 3a). The tumor size was significantly different according to the clusters (F= 5.0, p = 0.002; Fig. 4b). The sex was significantly associated with the clusters (chi-square = 34.9, p = 0.005; Fig. 4c). In Fig. 3b, the t-SNE plot showed some distinctive clusters were associated with M0 and M1c clusters. The statistical analysis also showed a significant association between M-stage and the clusters (chi-square = 23.6, p = 0.005; Fig. 4c). This means the pattern or site of metastasis could be predicted by extracted features by a DL model. Although there was no significant difference between EGFR mutation and each cluster, the t-SNE map showed a trend of association (chi-square = 4.2, p = n.s.; Figs. 3c and 4c). We showed that feature extraction and clustering were possible with only two MIP images of FDG PET. In addition, they were associated with the clinicopathological factors.

Discussion

As a proof-of-concept study, we extracted DL-based whole bode FDG PET features using two MIP images to overcome issues related to a large 3-D PET volume data. We showed that DL-based feature extraction that could reflect clinicopathological characteristics only with MIP images applied to a pre-trained CNN model, ResNet-50. Whole-body FDG PET contains a lot of non-pathologic information, and the clinical significance of some of it has not yet been fully understood or identified [15–18]. While these representations can be modeled through the DL model, whole-body PET data has not yet been widely applied to developing a DL model to extract features directly from whole-body image data. However, in this paper, DL-based feature extraction was performed with a relatively small volume of data without training a pre-trained model transfer.

Extracting discriminative features is key of DL especially CNN. CNN models trained on the ImageNet database are commonly used as backbone models for various vision tasks including image classification and recognition because they extract representations from natural images. Many DL models for medical images have employed this transfer learning strategy, and models pre-trained with ImageNet, such as ResNet-50 in this study, have been used. There were attempts to make a 3-D backbone model as it was limited to use them for large 3-D volume data [19]. Training on 3-D images is limited because the number of parameters is much larger and more data is required. Since it is a memory problem to process volume data on a general-scale graphic processing unit, the method of adjusting the input as a 2-D-based pre-trained CNN architecture has been widely used. Previous studies have utilized DL models to analyze limited field-of-view instead of whole-body level, such as tumor regions or thorax [20, 21]. One of the advantages of FDG PET is that it provides metabolic features at the whole-body level, including the metabolism of normal organs. This study contributes to an understanding of how to easily extract discriminative features using pre-trained CNNs for PET volumes at the whole-body level, which contain various clinicopathological information. Using MIP of PET volume is meaningful in mimicking real vision tasks. In PET reading in the clinical situation, MIP is widely used in visual interpretation for lesion detection and overall evaluation of the metabolic status of patients [22]. Extracting a pattern for a whole-body PET volume using MIP is similar to imitating a human vision task.

This approach could be used for various applications for designing models for biomarker extraction such as tumor burden as well as the classification process of PET images. Thus, we expect that this approach can be used as a backbone model for various DL-based analyses. This in itself could be used to create a new diagnostic classification system or to classify subtypes of diseases. Also, as shown in the above results, it can be used for filtering images taken in different postures or abnormal images such as those containing clinical artifacts. Finally, as a large-scale study using many FDG PET data, it can be used to find FDG PET images similar to the target representative image, referred to as content-based medical image retrieval [23]. As we already visualized by the t-SNE map (Fig. 1), an interactive explanation of PET images with a large database could support clinical readings as well as studies using FDG PET data.

Despite the promising results of our proof-of-concepts, there are several limitations to consider. First, our study only included lung cancer patients, so the generalizability of our findings to other types of cancer or diseases may be limited. Second, although our approach showed a simple method that utilizes FDG PET data in feature extraction and visualization, validation using larger datasets and external validation is required for generalization, including various PET machines as well as reconstruction algorithms. Lastly, we used a pre-trained CNN model, which may have limitations in capturing features specific to PET images. As various models have been developed for pretraining beyond CNN [24], another approach including pretraining for 3-dimensional data could be another option for extracting features from FDG PET data [25]. Collectively, the study analyzed baseline lung cancer FDG PET at a single center and found that DL-based feature extraction from whole-body FDG PET images using only anterior and lateral views of MIP images could be successful. We suggest that this approach could be used as the backbone model for various DL-based analyses of whole-body PET images, but further study using FDG PET from other centers, in other diseases, and under different clinical circumstances will be necessary.

Conclusion

A 2-D image-based pre-trained model could extract image patterns of whole-body FDG PET volume by using anterior and lateral views of MIP images. As the direct use of 3-D PET volume has difficulties in the requirement of large datasets and resources for the pretraining, our suggested approach leverages the existing pre-trained models trained by 2-D images that have been widely used in entire computer vision fields. These extracted patterns reflected clinicopathological factors. We suggest that this approach could be implemented as a backbone model for various applications for whole-body PET image analyses.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues from Seoul National University Hospital, who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Availability of Data and Material

Please contact author for data requests

Author Contributions

The study was designed by Hongyoon Choi. Material preparation and data collection and analysis were performed by Joonhyung Gil and Hongyoon Choi. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Joonhyung Gil. Review, editing, and supervision were performed by Jin Chul Paeng, Gi Jeong Cheon, and Keon Wook Kang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019K1A3A1A14065446), and Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (Project Number: 1711137870, KMDF_PR_20200901_0006-03).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Competing Interests

Joonhyung Gil, Hongyoon Choi, Jin Chul Paeng, Gi Jeong Cheon, and Keon Wook Kang declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study design of the retrospective analysis and exemption of informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (2105-157-1221). All procedures followed were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. The institutional review board waived the need to obtain informed consent.

Consent for Publication

The institutional review board waived the need to obtain informed consent because of the anonymity and the retrospective nature of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee J-G, Jun S, Cho Y-W, Lee H, Kim GB, Seo JB, et al. Deep learning in medical imaging: general overview. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:570–584. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarvamangala DR, Kulkarni RV. Convolutional neural networks in medical image understanding: a survey. Evol Intel. 2022;15:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s12065-020-00540-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arabi H, AkhavanAllaf A, Sanaat A, Shiri I, Zaidi H. The promise of artificial intelligence and deep learning in PET and SPECT imaging. Physica Medica. 2021;83:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee R, Shin JH, Choi H, Kim H-J, Cheon GJ, Jeon B. Variability of FP-CIT PET patterns associated with clinical features of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2021;96:e1663–e1671. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi H, Kim YK, Yoon EJ, Lee J-Y. Lee DS, for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Cognitive signature of brain FDG PET based on deep learning: domain transfer from Alzheimer’s disease to Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamdi M, Bourouis S, Rastislav K, Mohmed F. Evaluation of neuro images for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using deep learning neural network. Front Public Health. 2022;10:834032. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.834032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai Y-C, Wu K-C, Tseng N-C, Chen Y-J, Chang C-J, Yen K-Y, et al. Differentiation between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules by using automated three-dimensional high-resolution representation learning with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022;9:773041. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.773041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capobianco N, Meignan M, Cottereau A-S, Vercellino L, Sibille L, Spottiswoode B, et al. Deep-Learning 18F-FDG uptake classification enables total metabolic tumor volume estimation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:30–36. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.242412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawauchi K, Furuya S, Hirata K, Katoh C, Manabe O, Kobayashi K, et al. A convolutional neural network-based system to classify patients using FDG PET/CT examinations. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:227. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6694-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morid MA, Borjali A, Del Fiol G. A scoping review of transfer learning research on medical image analysis using ImageNet. Comput Biol Med. 2021;128:104115. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whi W, Choi H, Paeng JC, Cheon GJ, Kang KW, Lee DS. Fully automated identification of brain abnormality from whole-body FDG-PET imaging using deep learning-based brain extraction and statistical parametric mapping. EJNMMI Phys. 2021;8:79. doi: 10.1186/s40658-021-00424-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proc IEEE Comput Soc Conf Comput Vis Pattern Recognit. 2016:770–8.

- 13.Abadi M, Agarwal A, Barham P, Brevdo E, Chen Z, Citro C, et al. Tensorflow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2016;1603.04467.

- 14.van der Maaten L. Learning a parametric embedding by preserving local structure. Proc Twelfth Int Conf Artif Intell Statistics. 2009:384–91.

- 15.Shreve PD, Anzai Y, Wahl RL. Pitfalls in oncologic diagnosis with FDG PET imaging: physiologic and benign variants. RadioGraphics. 1999;19:61–77. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.1.g99ja0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purohit BS, Ailianou A, Dulguerov N, Becker CD, Ratib O, Becker M. FDG-PET/CT pitfalls in oncological head and neck imaging. Insights Imaging. 2014;5:585–602. doi: 10.1007/s13244-014-0349-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shammas A, Lim R, Charron M. Pediatric FDG PET/CT: physiologic uptake, normal variants, and benign conditions. RadioGraphics. 2009;29:1467–1486. doi: 10.1148/rg.295085247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin A, Rosenbaum SJ, Bockisch A. Physiological 18F-FDG uptake by the spinal cord: is it a point of consideration for cancer patients? J Neurooncol. 2012;107:609–615. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0785-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Ma K, Zheng Y. Med3d: transfer learning for 3d medical image analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2019; 1904.00625.

- 20.Kirienko M, Sollini M, Silvestri G, Mognetti S, Voulaz E, Antunovic L, et al. Convolutional neural networks promising in lung cancer T-parameter assessment on baseline FDG-PET/CT. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2018;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sibille L, Seifert R, Avramovic N, Vehren T, Spottiswoode B, Zuehlsdorff S, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT uptake classification in lymphoma and lung cancer by using deep convolutional neural networks. Radiology. 2020;294:445–452. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019191114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara T, Miyake M, Watanuki S, Mejia MA, Itoh M, Fukuda H. Easy detection of tumor in oncologic whole-body PET by projection reconstruction images with maximum intensity projection algorithm. Ann Nucl Med. 1999;13:199–203. doi: 10.1007/BF03164863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Q, Yang Y, Sun J, Yang Z, Zhang J. Using deep learning for content-based medical image retrieval. Medical Imaging 2017: Imaging Informatics for Healthcare. Res Appl. 2017(10138):270–80.

- 24.Shamshad, F., Khan, S., Zamir, S. W., Khan, M. H., Hayat, M., Khan, F. S., et al. Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2022; 2201.09873. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Singh SP, Wang L, Gupta S, Goli H, Padmanabhan P, Gulyás B. 3D deep learning on medical images: a review. Sensors. 2020;18:5097. doi: 10.3390/s20185097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact author for data requests