Abstract

Purpose

Hereditary tumor syndrome Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease is characterized by various benign and malignant tumors that are known to express somatostatin receptors (SSTR). We evaluated the role of 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan in patients with positive germline mutation of the VHL gene, presented initially or on follow-up, for the detection of recurrent or synchronous/metachronous lesions.

Methods

Fourteen patients (8 males; 6 females) with mean age 30 ± 9.86 years were retrospectively analyzed, were tested positive for VHL on gene dosage analysis, and underwent 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan for disease evaluation. The number and site of lesions were determined. The tracer uptake was analyzed semi-quantitatively by calculating the maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) of lesion.

Results

Four of the 14 patients underwent scan for initial diagnosis as baseline, 6 patients for post-therapy disease status, and 4 patients for initial diagnosis as well as follow-up evaluation of the disease. A total of 67 lesions were detected in 14 patients. The sites of lesions were cerebellar/vertebral/spinal (17; mean SUVmax = 7.85); pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (NET) (11; mean SUVmax = 20.64); retina (3; mean SUVmax = 10.46); pheochromocytoma (10; mean SUVmax = 16.32); paragangliomas (3; mean SUVmax = 10.65); pancreatic cyst (9; mean SUVmax = 2.54); and renal cyst (8; mean SUVmax = 1.56) and miscellaneous lesions constituted 6 lesions.

Conclusion

Our results show that 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT may be a useful modality for screening and follow-up of associated tumors in patients with germline gene mutation for VHL. It can be used as a one-stop imaging modality for VHL patients and may substitute for separate radiological investigations, making it more convenient for patients in terms of time and cost.

Keywords: Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT, Hemangioblastoma, SUVmax

Introduction

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, a familial neoplastic syndrome, is characterized by the presence of a variety of visceral cysts and benign and malignant lesions [1]. The transmission of VHL syndrome occurs in an autosomal dominant fashion due to germline mutations of a tumor suppressor gene located on the short arm of chromosome 3 (3p25–26) [2]. The penetration of VHL is > 90% by 65 years of age and the overall incidence is around 1 in 36,000 live births [1, 3–5].

The most common manifestation of VHL syndrome is central nervous system (CNS) hemangioblastomas (HB) that can affect 60–80% of all patients [3, 6]. The sites of CNS HB include the supra-tentorial region, cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, and lumbosacral nerve roots [1, 7]. Other frequently encountered tumors include retinal HB (25–60%), endolymphatic sac tumors (10%), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (NET) or cysts (35–70%), renal cell carcinoma (RCC) or cysts (25–60%), pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (10–20%), epididymal cystadenoma (25–60%), and broad ligament cystadenoma [1, 3].

Diagnosis is often clinical and relies mainly on imaging, although mutation analysis can be done. In patients with family history of VHL, presence of one tumor (HB, pheochromocytoma, or RCC) is sufficient to make the diagnosis. However, in cases with no family history, clinical diagnosis is established with the presence of at least two tumors, that is, two HB or one HB and one visceral tumor. Screening and surveillances are done with conventional imaging modalities such as ultrasound (USG), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) depending on the region to be examined [8, 9].

Neuroendocrine involvement of VHL is well established. The role of nuclear medicine in management has so far been limited mainly to screening or evaluation of pheochromocytoma and pancreatic NETs. While the former is evaluated using 123/131I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine single-photon emission computed tomography (MIBG SPECT) or SPECT/CT, the latter are evaluated using peptide receptor imaging based on over-expression of somatostatin receptors (SSTR) [10–12]. Accordingly, 68 Ga-1, 4, 7, 10-tetraazacyclododecane-N, Nʹ, Nʺ, Nʹʹʹ-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) peptide [tyr3-octreotate (TATE), 1-NaI3-octreotide (NOC), phe1-tyr3 octreotide (TOC)] positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), a functional imaging modality, has been employed in the detection of VHL-associated lesions [8, 12–15]. Few studies have reported the higher detection of VHL-associated lesions by this hybrid modality as compared to conventional modalities [8, 12–16]. However, the cohort studied is mostly small given the rarity of the disease. Published data exclusively on 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan in VHL is limited.

In view of this, in the present study, we aimed to retrospectively evaluate the role of 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT in patients with clinically suspicious/positive VHL syndrome in establishing the initial diagnosis, in follow-up for the detection of recurrent or synchronous/metachronous lesions, and in the evaluation of disease status.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection and Imaging Protocol

Patients with clinical suspicion/positive VHL disease who were referred to our department for 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan for further evaluation underwent the scan as per the following protocol.

The patients were administered 3–5 mCi of 68 Ga-DOTANOC intravenously. Scan was acquired 30–45 min post-injection of 68 Ga-DOTANOC on dedicated PET/CT scanners (Biograph mCT, Siemens Inc., Germany; and 710 Discovery PET/CT, GE, USA). Patients were positioned supine and whole body (from the vertex to mid-thigh) scans were acquired. Low-dose CT scan was acquired first with care dose parameters (80–120 keV; 150–300 mAs; pitch 1) followed by PET scan acquisition over 7–8 bed positions with 2–3 min per bed. The images were reconstructed with iterative reconstruction (3 iterations; 21 subsets).

All the 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scans conducted between 2017 and 2019 in patients with suspicious/known VHL were included in the study. The images were checked for any artifact and misregistration. The scans included either baseline or follow-up PET/CT scans and baseline as well as follow-up PET/CT scans whichever was available.

Image Analysis

68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan and clinical details of all the included patients were retrospectively analyzed by two experienced nuclear medicine physicians. Additionally, the findings of other imaging modalities such as CT/MRI/USG, whichever available, were analyzed with respect to the 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan findings. Any difference of opinion was resolved by discussion and consensus was reached.

Analysis of 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT was done using the following methods:

For semi-quantitative analysis, SUVmax was estimated by drawing region of interest (ROI) on the area of uptake. Three-dimensional ROI were drawn with 40% thresholding.

Visual analysis was performed on the basis of presence of anatomic lesion on CT scan as well as tracer uptake in the corresponding region on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET scan.

Clinical follow-up was obtained for all the included patients and was considered reference standard.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was done and continuous data (age; SUVmax) is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Discrete data in patient-wise and lesion-wise analysis is presented in terms of percentage. The organ-wise lesion count detected by conventional modalities and 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan was compared by t-test/Mann–Whitney/ANOVA. p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was done using SPSS software version 22.

Results

Twenty-four 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scans of 14 patients (6 females; 8 males) were analyzed for the study. Four of the 14 patients underwent the scan for initial diagnosis considered baseline and 6 patients underwent the scan for evaluation of disease status or restaging post-therapy while 4 patients underwent 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan for initial diagnosis as well as post-therapy evaluation of the disease (Fig. 1). Of 24 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scans in 14 patients, 9 patients underwent only one scan either at baseline or at follow-up (i.e., 4 baseline and 5 follow-up scans) and remaining 5 patients underwent baseline as well as follow-up scans, i.e., one patient had 2 scans, three patients have 3 scans, and another one had total 4 scans. Patients who were referred 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan for evaluation of disease status (N = 6) had undergone surgery prior to the scan. Mean age of the patients was 30 ± 9.86 years. The cohort demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Patient distribution based on indication for 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT. Rx, treatment; Dx, diagnosis

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

| Variable | Patients (n = 14) |

|---|---|

| Gender | Female = 6 |

| Male = 8 | |

| Age | 30 ± 9.86 years |

| (range = 15–45 years) | |

| Scan indication | |

| Baseline (for initial diagnosis) | 4 (28.5%) |

| Restaging (disease status post intervention) | 6 (43%) |

| Baseline + follow-up | 4 (28.5%) |

| Lesions detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT Scan | |

| CNS HB | 8 (57%) |

| Retinal angioma | 2 (14%) |

| Pheochromocytoma | 7 (50%) |

| Paraganglioma | 3 (21%) |

| NET pancreas | 7 (50%) |

| Pancreatic cyst | 9 (64%) |

| Renal cyst | 5 (36%) |

| Miscellaneous | 5 (36%) |

CNS HB, central nervous system hemangioblastoma; NET pancreas, neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas

Patients-Wise Analysis

Screening and surveillance are done with retinal angioma (14%) on 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma were detected in 7 (50%) and 3 (21%) patients, respectively. Pancreatic NET was detected in 7 of 14 patients (50%). Pancreatic and renal cysts were detected in 9 (64%) and 5 (36%) patients, respectively. Five patients (36%) had lesions at other sites (lymph nodes; thyroid; adrenal cyst; bone; liver cyst). Patient-wise division of lesions is given in Table 1.

Lesion-Wise Analysis

In 14 patients, 67 lesions were detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan. Cerebellar and/or spinal hemangioblastoma constituted 17 of total lesions (25%; mean SUVmax = 7.85). Three (4%) lesions were retinal angioma (mean SUVmax = 10.46). Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma constituted 10 (15%; mean SUVmax = 16.32) and 3 (4%; mean SUVmax = 10.65) of all lesions, respectively. Eleven (16%) lesions were NET of pancreas (mean SUVmax = 20.64). Pancreatic and renal cyst accounted for 9 (13%; mean SUVmax = 2.54) and 8 (12%; mean SUVmax = 1.56) lesions, respectively. Miscellaneous lesions constituted 6 (9%) lesions. The lesion-wise description along with their semi-quantitative analysis of various lesion sites detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scans of VHL patients is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lesion-wise analysis and semi-quantitative analysis of the tracer uptake in various lesion sites detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scans of VHL patients

| Lesion site | Lesion-wise analysis (%) | SUVmax (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| CNS HB | 25 | 7.85 ± 6.91 |

| Retinal angioma | 4 | 10.46 ± 8.03 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 15 | 16.32 ± 7.13 |

| Paraganglioma | 4 | 10.65 ± 7.26 |

| NET pancreas | 16 | 20.64 ± 13.33 |

| Pancreatic cyst | 13 | 2.54 ± 1.99 |

| Renal cyst | 12 | 1.56 ± 1.23 |

CNS HB, central nervous system hemangioblastoma; NET pancreas, neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas

Of the 67 lesions detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan, 28 lesions (42%) were detected on conventional modalities (ultrasound, MRI, CT, endoscopy, and/or MIBG) and were known prior to the 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan. Of the remaining 39 lesions, 30 were not detected as the region was not scanned on conventional modalities. Nine lesions detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan were not reported on conventional modalities (1 CNS HB; 1 pheochromocytoma; 2 paraganglioma; 3 pancreatic NET + cyst; 2 miscellaneous). Organ-wise detection of lesions on conventional imaging modalities and 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT is shown in Fig. 2. The number of lesions detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT was significantly higher than the number of lesions detected on conventional imaging modalities (p = 0.025).

Fig. 2.

Bar graph depicting relative detection of lesions and their various sites in conventional modalities (CM) vs 68 Ga-DOTANOC (DOTA) scan

Clinical Follow-up

68 Ga-DOTANOC scan was able to detect additional 43 lesions (64%) in 14 patients. In 8 of 14 patients, 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan helped in establishing/confirming clinical diagnosis of VHL. In the remaining 6 patients, 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan findings changed the course of management. In these 6 patients, clinical diagnosis of VHL had already been established by the clinician and they had undergone some treatment/intervention on the basis of conventional modalities prior to the 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan. As mentioned earlier, 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan was performed in these patients for restaging or for evaluation of disease status. The additional lesions detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan influenced the disease management, thereby affecting the outcome.

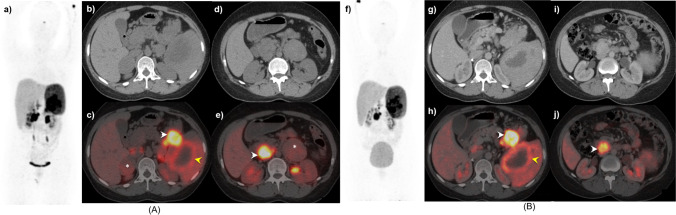

Figures 3, 4, and 5 A and B show the 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT images of patients referred for initial diagnosis; for the evaluation of post-surgery disease status; and for both initial diagnosis and post-treatment disease status of VHL, respectively.

Fig. 3.

A 33-year-old male with history of right cerebellar HB and clinical suspicion of VHL underwent 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT (a MIP image showing physiological distribution). Axial CT and fused PET/CT (b, c) images showing small hepatic cyst (white arrowhead) with no definite evidence of increased SSTR expression over and above the background liver uptake. Multiple non-DOTANOC avid pancreatic cysts (yellow arrowhead) noted in the body and tail of pancreas in axial CT and fused PET/CT (d, e) abdominal section images. Axial fused PET/CT (g) images of the brain reveal small hypodense foci of increased SSTR expression in left cerebello-pontine angle (white arrowhead) corresponding to well-defined hypodense lesion on CT (f), likely HB. Overall findings are consistent with clinical diagnosis of VHL

Fig. 4.

A 44-year-old male, known case of VHL with cerebellar HB, post lesionectomy, on follow-up, presented with suspicious pancreatic cysts on conventional imaging and no other known system involvement. Patient underwent 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT, MIP image (a) reveals foci of increased tracer uptake in the head region with heterogeneous tracer accumulation in bilateral kidneys. Axial sections of CT and fused PET/CT (b, c) at the level of pancreatic tail reveal multiple calcified pancreatic tail and hepatic cysts (white arrowheads) with faint to no significant SSTR expression. Axial sections of CT and PET/CT fused images (d, e) reveal similar non tracer avid pancreatic head and body cysts (yellow arrowhead) and bilateral kidneys (white arrowheads). Axial brain CT and fused PET/CT images (f, g) revealed post-operative cavity in the left cerebellum with tracer avid residual/recurrent disease along the periphery of cavity (white arrowhead). Sagittal PET/CT image (h) of the brain shows a focal area of SSTR expression in the right cerebellum (white arrowhead) as correlated with MIP—suggestive of recurrence in the brain missed as peri-lesional edema on MRI along with appearance of new lesion in the right cerebellum, pancreatic, and renal cysts

Fig. 5.

A 21-year-old female, with known VHL, underwent 68 Ga-DOTANOC A at baseline (MIP: a) and B post-operative follow-up (MIP: f). At baseline, CT and fused PET/CT axial images (b, c) reveal a hypodense right supra-renal lesion with mild tracer uptake (asterisk), intensely tracer avid hypodensity in the tail of the pancreas (white arrowhead), and an adjacent heterogeneous splenic lesion with peripheral tracer uptake (yellow arrowhead). Other.68 Ga-DOTANOC avid lesions seen in the lower sections in CT and fused PET/CT images (d, e) involving the left adrenal (asterisk) and an intensely avid precaval mass at the level of L2 vertebra (white arrowhead), suggestive of paraganglioma. Post bilateral adrenalectomy, follow-up axial CT and PET/CT images (g, h and i, j) revealed no residual disease in bilateral supra-renal regions with no significant interval change in the paraganglioma, pancreatic, and splenic lesions compared to baseline (stable disease)

Discussion

The current Dutch, Danish, and American guidelines for VHL disease recommend screening and periodic surveillance using imaging techniques such as MRI, CT, and USG for patients, as well as at-risk family members [17–20].

In the present study, we aimed at retrospectively evaluating the role of 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT scan in initial diagnosis and subsequently for monitoring the disease status as follow-up. Previously, few studies have demonstrated the importance of 68 Ga- DOTATATE PET/CT in VHL [8, 16, 21–26]. However, there is still paucity of literature on this subject.

VHL-associated tumors involve the brain, spine, eyes, ears, kidneys, pancreas, adrenal glands, liver, and/or reproductive tract. The lesions can be presented as benign or malignant. This requires the screening and surveillance of VHL to be multisystemic. While a multidisciplinary approach is necessary, any one conventional imaging modality (USG, CT, and MRI) may not be adequate. A major disadvantage of these modalities is they are often used for regional scan such as USG and CT for the abdomen and MRI for the brain. For overall screening, the patient has to undergo multiple scans on one or more modalities that is time-consuming and inconvenient and may not be cost-effective for the patient. Furthermore, these modalities yield structural information and do not assess the functional/physiological status of the lesions.

68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT can plug these lacunae in conventional imaging, as it is a hybrid modality that provides both structural and functional information of the lesions. Furthermore, the default imaging protocol involves whole body scanning (from the vertex to mid-thigh) which enables multisystemic evaluation of the patient in a single sitting, making it more convenient and cost-effective for the patient [8].

In the present study, 68Ga-DOTANOC detected 67 VHL-associated lesions in 14 patients. Of the 14 patients, 4 patients underwent scan for initial diagnosis, 6 patients for restaging, and 4 patients for both initial diagnosis and follow-up. All the patients had undergone at least one conventional imaging prior to the 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan. The organ-based prevalence of the VHL-associated tumors observed in our study (Table 1) is similar to that reported in literature [6].

Of the 67 lesions detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan, only 28 (42%) were already known on conventional imaging modalities. 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT detected additional 39 (58%) lesions that had an impact on the management of the patients. The majority of lesions were missed on conventional imaging due to regional scans unlike PET/CT in which whole body (vertex to mid-thigh) is scanned in single sitting. The lesions detected on conventional modalities were also detected on 68 Ga-DOTANOC scan. Furthermore, the detection rate of 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT was significantly higher (p = 0.025) than of conventional modalities for all VHL-associated tumors.

Few studies have reported 68 Ga-DOTATATE/DOTATOC PET/CT to have a higher sensitivity, specificity, and detection rate than that of MRI and CT in detecting VHL-associated tumors [8, 16]. In a recent study by Shell et al. [8], 68 Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT was found to have significantly higher detection rate when compared with anatomic imaging for all lesions, and comparable detection rate for pancreatic lesions in VHL patients [8]. These reports are in consensus with our results.

In light of these results, we suggest that 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT has a much larger role to play in management of VHL than it currently does. It should be considered the first-line and single point modality for diagnosis, staging, and restaging as well as response evaluation for all VHL-associated tumors instead of being limited to NETs.

The present study has certain limitations. Firstly, it has a small sample size. The study is heterogeneous as the included population has VHL patients for initial diagnosis and restaging as well as follow-up. Since the study is retrospective in nature, 68 Ga-DOTANOC comparison was made with any of the three conventional modalities (CT/MRI/USG) that the patients had undergone prior to the PET/CT scan. Furthermore, conventional imaging usually involves regional scanning instead of whole body scanning in PET/CT. Hence, one-to-one lesion comparison could not be made. However, despite these limitations, the present study underlines the importance of this hybrid molecular whole body imaging modality, 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT, in the screening and surveillance of VHL disease.

Conclusion

The present study shows that 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT may be a useful modality for overall screening and follow-up of VHL syndrome. Being a hybrid modality and the default whole body scanning protocol, PET/CT can be used as one-stop imaging modality for VHL patients and may substitute for separate radiological investigations, making it more convenient for patients in terms of time and cost. However, prospective studies with larger cohort are warranted to establish the clear advantage of 68 Ga-DOTA peptide PET/CT over stand-alone conventional modalities in the screening and surveillance of VHL patients.

Author Contribution

In this study, 11 authors have made their contributions and we hereby certify that there is a significant contribution by all the authors in the study as given below:

Shamim Ahmed Shamim (corresponding author): conception and design of study, data interpretation, and writing the manuscript.

Geetanjali Arora: analysis of data, data interpretation, and writing the manuscript.

Naresh Kumar: data collection; data compilation, writing and revising the manuscript.

Jhangir Hussain: collection and compilation of data.

Shreya Datta Gupta: data interpretation and writing the manuscript.

Arun Raj ST: data interpretation.

Kritin Shankar: writing the manuscript.

Alpesh Goyal: data interpretation and clinical correlation of image findings.

Rajesh Khadgawat: conception and design of study.

Sambit Sagar: writing the manuscript.

Chandrasekhar Bal: conception and design of study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Shamim Ahmed Shamim, Geetanjali Arora, Naresh Kumar, Jhangir Hussain, Shreya Datta Gupta, Arun Raj ST, Kritin Shankar, Alpesh Goyal, Rajesh Khadgawat, Sambit Sagar, and Chandrasekhar Bal declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The participants signed consent regarding publishing their data (and/or photographs).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shamim Ahmed Shamim, Email: sashamim2002@gmail.com.

Geetanjali Arora, Email: a.geetanjali@gmail.com.

Naresh Kumar, Email: nchaudhary378.nc@gmail.com.

Jhangir Hussain, Email: jahangeer78697@gmail.com.

Shreya Datta Gupta, Email: dgshreya90@gmail.com.

Arun Raj ST, Email: arunrajst@gmail.com.

Kritin Shankar, Email: kritin23@gmail.com.

Alpesh Goyal, Email: alpeshgoyal89@gmail.com.

Rajesh Khadgawat, Email: rajeshkhadgawat@hotmail.com.

Sambit Sagar, Email: drsambitofficial@gmail.com.

Chandrasekhar Bal, Email: drcsbal@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260:1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maher ER. Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30:1987–90. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00391-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, Benjamin C, Harris R, Moore AT, et al. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. QJM. 1990;77:1151–1163. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann HPH, Wiestler OD. Clustering of features of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: evidence for a complex genetic locus. Lancet. 1991;337:1052–1054. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91705-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varshney N, Kebede AA, Owusu-Dapaah H, Lather J, Kaushik M, Bhullar JS. A review of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2017;4:20–29. doi: 10.15586/jkcvhl.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chittiboina P, Lonser RR. Von Hippel–Lindau disease. In: M.P. Islam and E.S. Roach, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology: neurocutaneous syndromes; 2015; 132 (3): pp. 139–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Shell J, Tirosh A, Millo C, Sadowski SM, Assadipour Y, Green P, et al. The utility of 68Gallium-DOTATATE PET/CT in the detection of von Hippel- T Lindau disease associated tumors. European J Radiology. 2019;112:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma P, Dhull VS, Bal CS, Malhotra A, Kumar R. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: demonstration of entire disease spectrum with 68Ga-DOTANOC PET-CT. Korean J Radiol. 2014;15:169–172. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2014.15.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sizdahkhani S, Feldman MJ, Piazza MG, Ksendzovsky A, Edwards NA, Ray Chaudhury A, et al. Somatostatin receptor expression on von Hippel-Lindau-associated hemangioblastomas offers novel therapeutic target. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40822. doi: 10.1038/srep40822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambrosini V, Campana D, Allegri V, Opocher G, Fanti S. 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET/CT detects somatostatin receptors expression in von Hippel-Lindau cerebellar disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:64–65. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181fef14a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadakis GZ, Millo C, Jassel IS, Bagci U, Sadowski SM, Karantanas AH, et al. 18F-FDG and 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in von Hippel-Lindau disease–associated retinal hemangioblastoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:189–190. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadakis GZ, Millo C, Sadowski SM, Bagci U, Patronas NJ. Endolymphatic sac tumor showing increased activity on 68Ga DOTATATE PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:783–784. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadakis GZ, Millo C, Sadowski SM, Bagci U, Patronas NJ. Epididymal cystadenomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease showing increased activity on 68Ga DOTATATE PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:781–782. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadakis GZ, Millo C, Sadowski SM, Bagci U, Patronas NJ. Kidney tumor in a von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) patient with intensely increased activity on 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:970–971. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad V, Tiling N, Denecke T, Brenner W, Plöckinger U. Potential role of 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in screening for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:2014–2020. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hes FJ, van der Luijt RB, Lips CJ. Clinical management of Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. Neth J Med. 2001;59:225–234. doi: 10.1016/S0300-2977(01)00165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lammens CR, Aaronson NK, Hes FJ, Links TP, Zonnenberg BA, Lenders JW, et al. Compliance with periodic surveillance for Von-Hippel-Lindau disease. Genet Med. 2011;13:519–527. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182091a1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poulsen M, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Bisgaard M. Surveillance in von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) Clin Genet. 2010;77:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VHL Family Alliance. The VHL Handbook: what you need to know about VHL. In: The VHL Alliance. 6th edition; revised 2020: pp. 14–15.

- 21.Ilhan H, Fendler WP, Cyran CC, Spitzweg C, Auernhammer CJ, Gildehaus FJ, et al. Impact of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT on the surgical management of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas or ileum. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:164–171. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haug AR, Cindea-Drimus R, Auernhammer CJ, Reincke M, Wängler B, Uebleis C, et al. The role of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in suspected neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1686–1692. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.101675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mojtahedi A, Thamake S, Tworowska I, Ranganathan D, Delpassand ES. The value of (68)Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors compared to current FDA approved imaging modalities: a review of literature. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;4:426–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofman MS, Kong G, Neels OC, Eu P, Hong E, Hicks RJ. High management impact of Ga-68 DOTATATE (GaTate) PET/CT for imaging neuroendocrine and other somatostatin expressing tumours: management impact of GaTate PET/CT. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012;56:40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid-Tannwald C, Schmid-Tannwald CM, Morelli JN, Neumann R, Haug AR, Jansen N, et al. Comparison of abdominal MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging to 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in detection of neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:897–907. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadowski SM, Neychev V, Millo C, Shih J, Nilubol N, Herscovitch P, et al. Prospective study of 68 Ga-DOTATATE positron emission tomography/computed tomography for detecting gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and unknown primary sites. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):588–596. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.