Abstract

A 3D-supramolecular nickel integrated Ni-SDZ complex was synthesized using sodium salt of sulfadiazine as the ligand and nickel(II) acetate as the metal salt using a condensation process and slow evaporation approach to growing the single crystal. The metal complex was characterized for its composition, functional groups, surface morphology as well as complex 3D structure, by resorting to various analytical techniques. The interacting surface and stability as well as reactivity of the complex were carried out using the DFT platform. From ADMET parameters, human Intestinal Absorbance data revealed that the compound has the potential to be well absorbed, and also Ni-SDZ complex cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Additionally, the complex's DNA binding affinity and in-vivo and in-vitro cytotoxic studies were explored utilizing UV–Vis absorbance titration, viscosity measurements, and S. pombe cells and brine shrimp lethality tests. In visible light radiation, the Ni-SDZ complex displayed exceptional photo-degradation characteristics of approximately 70.19% within 70 min against methylene blue (MB).

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Chemistry

Introduction

Organometallic compounds have piqued the interest of researchers due to their extraordinary properties such as large surface area, crystallinity, and antibacterial activity1–3. Sulfonamides, an organic sulfur-containing compound radical –SO2NH2–, derived from chiefly sulfanilamide, having a similar molecular structure to P-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), are capable of interfering with the metabolic processes in bacteria. They act as antimicrobial agents by inhibiting bacterial growth and activity and are called sulfa drugs4. Sulfonamides are used in the prevention and treatment of bacterial infections, diabetes mellitus, edema, hypertension, gout, allergies, and cough, as well as antifungal and antimalarial5–16 Sulfadiazine, a member of the triple sulfa drug family (sulfamerazine, sulfamethazine, and sulfadiazine) used as an antibacterial agent. In combination, sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine are used to treat toxoplasmosis, a disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii17,18 It is capable of inhibiting the growth or reproduction of bacteria but not killing the bacteria. It blocks the synthesis of bacterial dihydrofolic acid and therefore Figure S1 (Supplementary information). The lack of access to safe drinking water is one of the major health concerns of modern life. One of the most common compounds that renders water unsafe for drinking is industrial dyes. Methylene blue (MB), one of these dyes, poses the greatest risk to human health and environmental security since it is poisonous, carcinogenic, and non-biodegradable. It is typically discharged into natural water sources, endangering the health of both people and other living things. Therefore, it is necessary to create an effective, ecologically acceptable method of eliminating MB and other dyes from wastewater. A popular advanced oxidation method for removing dye is photodegradation. The full mineralization of the dye into simple, non-toxic species has the advantage of potentially lowering the cost of processing. Transition metal complexes have a wide range of applications in materials and biological sciences19–22. In the search for novel therapy against resistant organisms, the existing drug attempted to modify by incorporating metal on it. The presence of metal ions helps to accelerate drug action23–28. The metal complexes of sulfadiazine, especially silver sulfadiazine used in burn therapy, and zinc sulfadiazine used in the prevention of bacterial infection in burned animals29–32. The intercalation of transition metal complexes of sulfonamide derivatives into DNA has been a topic of major bioinorganic interest in the past two decades and continues to obtain much attentions33–38. Also, the transition metal complex and its nanocomposite-based photocatalysts have recently been established for the breakdown of the dye contained in wastewater. Because of energy and environmental concerns, the usefulness of metal complexes as a catalyst for photochemical processes has been widely researched. Metal complexes and their nanocomposite-based photocatalysts include UV-active and visible-responsive photocatalysts that are used to degrade organic contaminants. Transition metal-based complexes and composites are explored in visible and UV-active photocatalysis. This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of the sprd-free ligand once the metal is incorporated into it, to enhance both the biological activity and the photodegradation potential for a chosen organic dye, methylene blue (MB), within an aqueous solution. The metal complex (Ni-SDZ) properties such as Homo–Lumo energy have been calculated to get a better understanding of the properties of the Ni-SDZ molecule. Also, NBO analysis is the study of an intramolecular delocalization of hyper-conjugation. Hirshfeld surface analysis and their related 2D fingerprint plots evaluated the intermolecular interactions. Furthermore, we conclude from the magnetic behaviour of the nickel complex of sulfadiazine, the coordination environment surrounding nickel is distorted octahedral. The interaction of the nickel complex of sulfadiazine with DNA has improved much attention due to their possible applications as new therapeutic agents. In the present work, we have concluded the nature of ligands is of dominant importance in the interaction of the complex with DNA molecule. The DNA-binding of the complex has been studied using absorption titration and viscosity measurements are also reported.

Experimental details

Materials and instrumentations

Sodium salt of sulfadiazine (SDZ) (Sigma, purity of the compound was > 99%), nickel(II) acetate (Alfa Aezar, purity of the compound was > 99%), and other reagents are of the highest grade commercially available and used without further purification. FT-IR spectra were recorded on Perkin Elmer Spectrum GX FT-IR spectrometer using the KBr pellet technique. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectra were recorded at X-band frequencies with a JES—FA200 ESR Spectrometer. Magnetic measurements were performed on a Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) at room temperature. The crystal structure of the nickel complex of sulfadiazine was determined using Bruker Kappa Apex-II CCD-4 diffractometer using graphite-monochromatic MoKα radiation at room temperature (293 K).

Preparation of Ni-SDZ complex

The complex was synthesized using the reflux method at 60–70 °C. The aqueous nickel acetate (1 mmol) solution was added dropwise to a methanol–water solution of sodium salt of sulfadiazine (2 mmol) with constant stirring. The formed precipitate was separated from the solution by filtration, washed, and dried in a desiccator over CaCl2. The complex was insoluble in water and in most of the common organic solvents but soluble in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and dimethylformamide (DMF). The solid precipitates were dissolved in 3-methyl pyridine and left to crystallize. After four weeks, greenish square crystals were obtained and picked up for single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Light Green solid yield (70%).

(SDZ ligand) FT-IR (cm−1): 3103 (NH), 3423 νas(NH2), 3355 νs(NH2), 1652 δ(NH2), 1580, 1490 ν-phenyl ring, 1325, 1262 (SO2)as, 1156 (SO2)sy, 996, 942 ν(S–N). (Ni-SDZ complex) FT-IR (cm−1): 3438 νas(NH2), 3299 νs(NH2), 1628 δ(NH2), 1583, 1598 ν-phenyl ring, 1354, 1274 (SO2)as, 1179 (SO2)sy, 1016, 990 ν(S–N), 481 (M–N)1. UV–Vis: λmax (DMSO) nm: 259.

X-ray diffraction analysis

Diffraction data were collected on a Bruker Kappa Apex-II CCD-4 diffractometer using graphite-monochromatic MoKα radiation (0.71073 Å) at 293(2) K39. The good quality of the crystal is reflected by the comparatively low value of the Rint parameter. The structure is solved by direct methods (SHELXS-97) and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods on |F|2 with all non-hydrogen atoms anisotropic (SHELXL-97)40. Hydrogen atoms are located from difference maps and refined isotropically. The calculations are performed using the WinGX crystallographic software package41. Crystal data and structure refinement results for the compound are summarized in Table 1. The pictures are made with ORTEP-III42. Crystallographic data in CIF format are deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, CCDC No. 1552740.

Table 1.

Preliminary crystallographic data and refinement parameters.

| Chemical name | Nickel (4-amino-N-pyrimidin- 2-yl-benzenesulfonamide) (3-methyl Pyridine) |

|---|---|

| Chemical formula | Ni0.5 (C10H10N4O2S) (C6H7N) |

| Molecular weight | 743.5 amu |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/c |

| a | 8.8364 (10)Å |

| b | 18.27001 (20) Å |

| c | 13.7006(12)Å |

| β | 121.753 (5) |

| Volume (V) | 1881.21 (69) Å3 |

| Z | 2 |

| ρc (Mg/cm3) | 1.31 |

| µ mm-1 | 0.68 |

| F(000) | 772 |

| Size of the crystal | 0.34 × 0.15 × 0.05 mm |

| θ range for data collection (°) | θmin = 2.1°, θmax = 25.0° |

| Total number of measured reflections | 9258 |

| Total number of independent reflections | 3315 |

| h | − 10 to 10 |

| k | − 11 to 21 |

| l | − 15 to 16 |

| Number of parameters | 224 |

| Goodness of fit on |F|2 | 1.2 |

Computational analysis

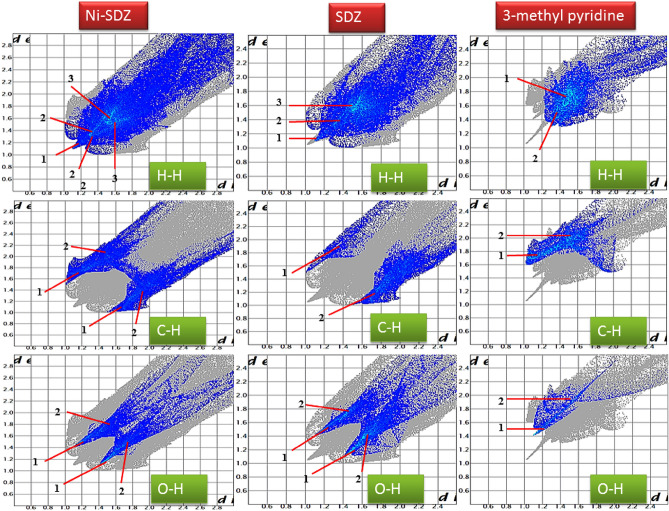

The Hirshfeld surfaces of the molecule are generated by Crystal Explorer 3.143. The two-dimensional fingerprint plot for Ni-SDZ molecule, SDZ, and 3-methyl pyridine (Solvent) displays the contributions from different contacts: All, H…H, O…H, C…H and N…H, which investigates the intermolecular contacts and gives a quantitative summary of nature and type of intermolecular contacts qualified by the molecules in the crystal. The fingerprint plot is based on the de (distance from the point to the nearest nucleus external to the surface) and di (the distance to the nearest nucleus internal to the surface). The value of dnorm is depending on the intermolecular contacts being less than, greater than, and equal to the van der Waals separations and is shown by the surface with a red spot representing shorter contacts, white areas representing contacts around the van der Waals separation, and blue regions are devoid of close contacts. The surface shape index and curvedness highlighted the C–H…π and π…π intermolecular interactions respectively44,45. All the calculations of an optimized structure of Ni-SDZ molecule were performed using the Jaguar program as built in the Schrödinger package software at B3LYP/LAV2P* level of theory46–50. The wide energy difference between Homo and Lumo is pointing towards the stability of the molecule. Natural bond orbital (NBO) calculation program incorporated in Schrödinger software package.

ADMET-SAR parameter

The pharmacokinetic properties, such as Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) of the compound were predicted using the preadmet. This tool is a convenient platform for biochemical and drug discovery research investigations. Various chemical-physical characteristics of the compound along with ADMET and toxicity were predicted51.

DNA interaction studies

The stock solution of DNA-polymerized CT-DNA was prepared by dissolving DNA in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.4 and kept for 24 h. The DNA solution was stored at 4 °C and used within 5 days of preparation. CT-DNA solutions gave a ratio of UV absorbance ~ 1.8 at 260 and 280 nm, indicating that DNA was sufficiently free from protein. The nucleotide concentration was determined by UV absorption spectroscopy using the molar absorption coefficient (ε = 6600 M−1 cm−1) at 260 nm. The ability of the Ni-SDZ complex to interact with CT-DNA was studied by UV–Vis. absorption titration and viscosity measurements according to the literature procedure52,53. The absorption spectra of the Ni-SDZ complex were recorded between 200 and 800 nm. The UV–Vis absorption titrations were carried out with a constant concentration of the test complex (5.0 × 10–5 M) and various concentrations of CT-DNA (0 to 2.5 × 10–5 M). Viscosity measurement was performed in the thermostatic viscosity bath maintained at 37 °C using Ubbelohde viscometer by measuring the flow time of DNA in Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.2. The flow time of each sample was automatically measured with three repetitions and the viscosity of the samples was computed by the average values of three measurements. The results were presented as relative specific viscosity (η/η0)1/3 against19/[DNA] = 0, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, 2.0, where η and η0 are the specific viscosities of DNA in the presence and absence of the compound respectively54–58.

Cytotoxic studies

The cellular level bioassay was carried out using S. pombe cells. The cells were grown in 50 mL yeast extract media in a 150 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The flask was incubated at 30 °C on a shaker at 150 rpm till the exponential growth of S. pombe was obtained (24–30 h). The cell culture was treated with different concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 mg mL−1) of complexes, free ligands, and DMSO (control) and incubated for 16–18 h. Brine shrimp lethality assay is an important tool for the preliminary cytotoxicity assay based on the ability to kill a laboratory-cultured larva (nauplii). Experiments were concluded with control and different concentration of the complexes. The whole set was triplicated to get an accurate result. The LC50 was determined from the best-fit line, a graph of % mortality against the concentration. The LC50 value was obtained from the antilogarithm of log19 at 50% mortality (LC50). All data were collected from three independent experiments59–61.

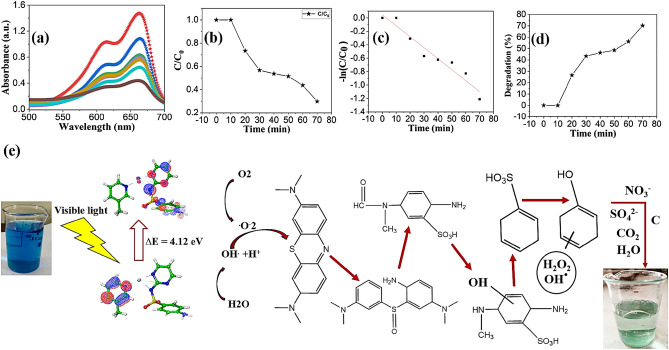

Photocatalytic degradation of MB

The photocatalytic activities of Ni-SDZ complex-based photocatalysts were calculated by the photodegradation of MB dye under a 24 W lamp irradiation (visible light) in the open air and at room temperature. The distance between the light source and the beaker containing the reaction mixture was fixed at 3 cm. The Ni-SDZ (0.1 g) metal complex photocatalysts were dispersed into 100.0 ml MB (10 PPM) aqueous solutions. Before irradiation (visible light), all three suspensions were magnetically stirred in the dark for 10-min in acetone to ensure the establishment of equilibrium and then were heated to evaporate the acetone until the three separately prepared compounds were deposited in the bottom of the beaker. Samples were withdrawn at regular intervals (20 min) for UV analysis.

Results and discussion

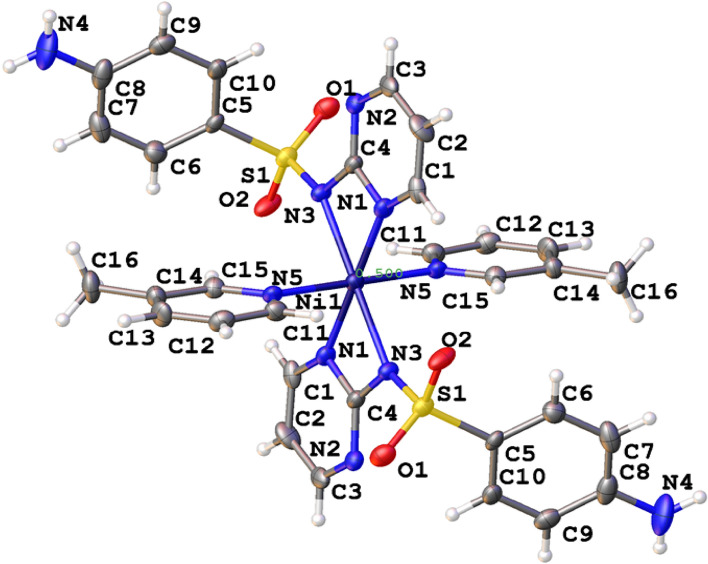

Crystal structure of [Ni(SDZ)2(3-methyl pyridine)2]

The crystal structure of the Ni-SDZ molecule and the atom numbering scheme are shown in Fig. 1. The preliminary and intensity data of crystallography are given in Table 1. The Ni(II) ion in the Ni-SDZ molecule exhibits a distorted-octahedral environment. The primary ligand sulfadiazine (SDZ) acts as a bidentate sulfonamide ligand and it is coordinated with the sulfonamide N1 and N3 [Ni–N(1) = 2.073(5)Å; Ni–N(3) = 2.145(5)Å]. The apical position is occupied by a 3-methyl pyridine solvent molecule that coordinates metal and its bond distance surrounding the nickel atom is Ni–N(5) = 2.078(5) Å, and the molecule completes the coordination sphere. In the Ni-SDZ molecule, the bond length of the benzene ring is slightly greater than the free SDZ ligand, whereas distances S(1)–N(1) = 1.614(5) Å, is slightly less than the free SDZ ligand. In the reported molecule (Ni-SDZ), bond length of S1–O1 = 1.441(5) Å and S1–O2 = 1.446(4) Å is slightly greater than the free SDZ ligand. Also, the bond angle of O1–S1–O2, O1–S1–C5, O2–S1–C5, and C5–S1–N3 is nearly equal to the free SDZ ligand62. The selected bond parameters surrounding the Ni(II) in [Ni(SDZ)(3-methyl pyridine)] with experimental (X-ray) and Computational (B3LYP) data are reported in Table 2.

Figure 1.

ORTEP View of Ni-SDZ molecule showing the numbering scheme of their displacement ellipsoids at the 50% probability level.

Table 2.

Bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) surrounding the Ni(II) in Ni-SDZ molecule with experimental (X-ray) and theoretical (B3LYP) data.

| Atom | X-ray | B3LYP | Atom | X-ray | B3LYP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni1—N1 | 2.073 (5) | 2.123 | N1—Ni1—N5 | 91.2 (2) | 89.878 |

| Ni1—N5 | 2.078 (5) | 2.099 | N1—Ni1—N3 | 63.63 (18) | 62.653 |

| Ni1—N3 | 2.145 (5) | 2.193 | N5—Ni1—N3 | 90.6 (19) | 91.958 |

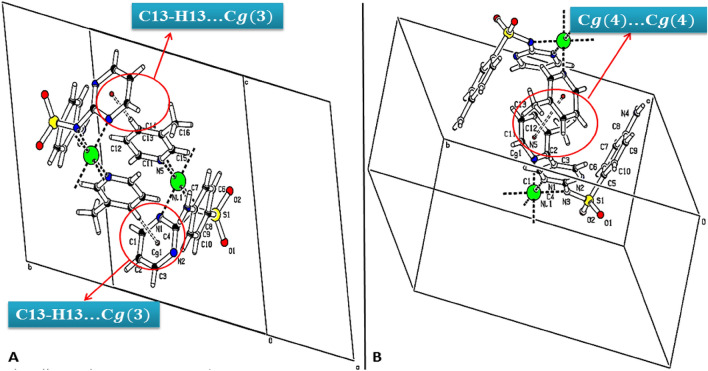

The stereochemistry of the sulfur atom is as usual a slightly distorted tetrahedral geometry with the bond parameters involving sulfur lying within the range quoted in the literature63,64. The maximum and minimum values of angles around the sulfur atom are O1–S1–O2 and O2–S1–N3 116.6(3) Å and 105.2(3) Å respectively for Ni-SDZ and the S–N bond length is similar to that found in reported structure [Ni(C10H9N4O2S)2(C5H5N)2]·0.5H2O65. Intramolecular and intermolecular interactions play a vital role in the stability of crystals. Few intermolecular interactions like Π…Π [Cg(4)–Cg(4)] and C–H…Π [C(13)–H(13)–Cg(3)] also help in the stability of the molecule and their relevant distance are 3.791 Å and 2.57 Å respectively. The C–H…Π [C(13)–H(13)–Cg(3)] interaction distance (2.57 Å) in the present molecule which is quite lesser than the distance in the reported crystal structure (C–H–Cg distance of 3.605(7) Å)66. The C–H…Π and Π…Π Interactions are presented in Fig. 2. The molecular structure shows the heterocyclic ring is planar. The nickel is in a similar plane as the four coordination 3-methyl pyridine nitrogen. The angles to the least square plane through nickel, sulfonamide, and heterocyclic nitrogen [N1–Ni–N1i] are 1.2(4)°, and 180(4)° respectively and the angle between sulfonamide and 3-methyl pyridine nitrogen is almost perpendicular [N1–Ni1–N5 = 91.2(2)°] (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Crystal packing of Ni-SDZ molecule showing (A) C–H···π and (B) π…π Interactions.

Figure 3.

Packing diagram of Ni-SDZ molecule containing an orthogonal view of ligand (sulfonamide) and solvent (3-methyl pyridine).

FT-IR spectral analysis

To clarify the mode of bonding and the effect of the nickel ion on the SDZ ligand, the IR spectra of the SDZ ligand and their nickel complex are calculated and assigned based on a careful comparison of their spectra with that of the SDZ ligand. The infrared spectra (FT-IR) of the nickel complex taken in the region 4000–400 cm-1 are compared with the SDZ ligand. Based on some general references33,34 and earlier studies of complexes with sulfonamide derivatives67–70, a tentative assignment of the best important bands is given in Figure S2. The symmetric and asymmetric bands assigned to ν(NH2) in SDZ ligand (3496 and 3317 cm−1) are shifted to wave numbers in the nickel complex (3490 and 3382 cm−1), representing the NH2 group are modified to the free SDZ ligand. These modifications are probably owing to the hydrogen bonding between complexes involving the NH2 and SO2 groups. The scissoring vibrations for the amino (–NH2) group seem at 1625 cm−1 and the peak due to the phenyl ring is at 1530 cm−1. The peaks at 1339 cm−1assigned to νasym(SO2) and those at 1154 cm−1 to νsym(SO2) show important changes upon complexation. The 1066 cm−1 band in the ligand is assigned to ν(S–N)71 at higher frequencies. These shifts to higher frequencies are in accord with the shortening of the S–N bond lengths which have been observed in the respective crystal structure of the complex. Also, the presence of 406 cm−1 in Ni-SDZ spectra indicates metal–ligand binding which is absent in the spectra of SDZ ligand60,72.

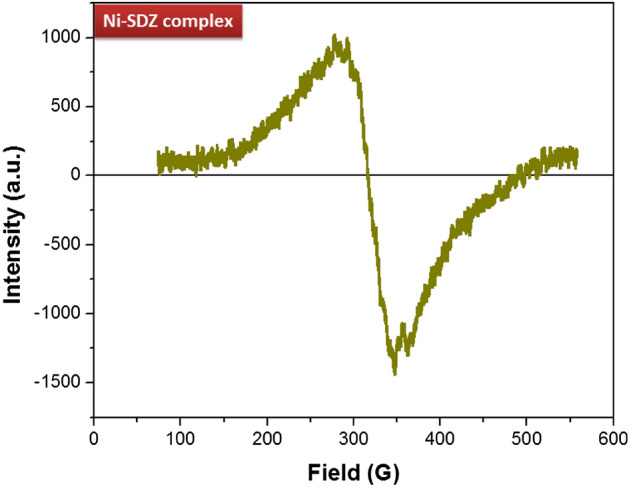

Magnetic behavior studies

The room temperature X-band EPR spectrum of the nickel complex is shown in Fig. 4. The EPR spectrum of the Ni-SDZ complex is exhibiting both parallel and perpendicular g tensor values which are 2.371 for gparallel and 1.942 for gperpendicular. The experimental g values were gparallel > gperpendicular > 2.0023 which indicates that the nickel has a ground state characteristic for octahedral or square planar geometry. Also, we compute the gavg = 2.085 with the help of equation g2avg = 1/3[2g2perpendicular + g2parallel]. The gparallel > gperpendicular value suggests the octahedral environment of the nickel complex of SDZ73,74.

Figure 4.

Electron paramagnetic resonance spectra (EPR) of nickel complex of SDZ.

The magnetic behavior of the complex was studied at room temperature (293 K) (Figure S3). The summary of the results on the magnetic behaviour of the nickel complex was given by Figgis and Nyholm75. The experimental values of the magnetic moment for nickel complexes are generally revealing of the coordination geometry of the metal. Nickel must exhibit a magnetic moment higher than that expected for two unpaired electrons in octahedral (2.80–3.20 B.M) and tetrahedral (3.40–4.20 B.M.) complexes, while its square planar complexes would be diamagnetic. The magnetic moment observed for the nickel(II) complex is 2.83 B.M which is consistent with the octahedral stereochemistry of the complex. Also, The nature of the graph of magnetic susceptibility: χ = M/H with a slope of 2.227 × 10–7, reveals that the complex possesses paramagnetic properties.

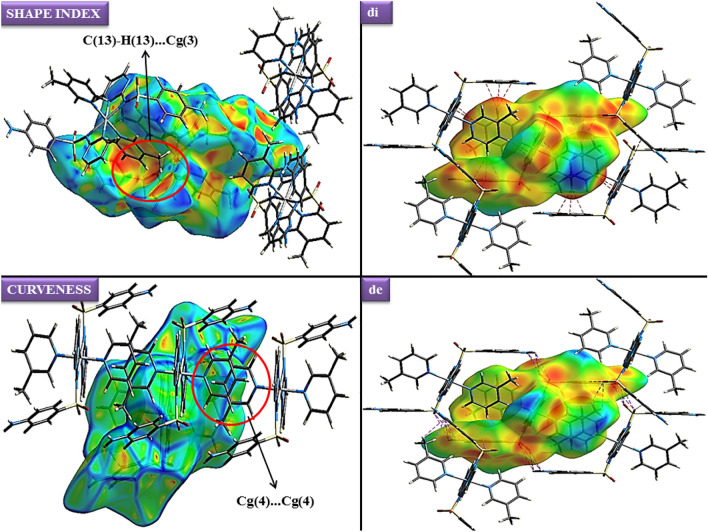

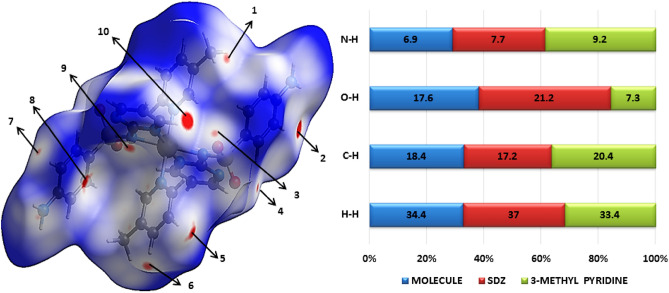

Hirshfeld surface analysis

Hirshfeld surface analysis and their correlated 2D fingerprint plots76 have been performed to study the nature of the intermolecular interactions and their measurable contributions towards the crystal packing. The Hirshfeld surfaces (shape index, curvedness, di, and de) of the Ni-SDZ molecule are depicted in Fig. 5. The shape index and curvedness plots are significant indicators for the C–H…π interactions and π…π stacking within the crystal lattice77. There are touching pair of triangles (blue and red) for the shape index and the curvedness surfaces display broad, relatively flat regions characteristic of π-stacking of molecules. One of the significant interactions in the molecule is between C…H/H…C atoms with the distances of 1.08 Å and 1.45 Å for H to di surface and C to di surface respectively and so, the total distance of C…H/H…C interactions is 2.53 Å. The dominant interactions N–H…O and C–H…O is observed on the de surface. The distance of O…H (N–H…O) is 2.55 Å and the distances of O to de and de to H are 1.438 Å and 1.11 Å respectively. The normalized contact distance (dnorm) is based on both de and di. The surface represented by a deep red spot is illuminating hydrogen bonding interactions (Fig. 5)58,78. The dominant interactions are H…O can be seen in di and de surface plots as the bright red spots and deep red spots in maps are showing strong interactions in molecules. The column chart shows the percentage contributions of various contacts of the molecule (Ni-SDZ molecule), SDZ, and 3-methyl pyridine (Solvent) in Fig. 6. The red spot in the dnorm surface (Fig. 6) is attributed to weak hydrogen bonds involving the acceptor oxygen and nitrogen atom from the sulfonyl group and the hydrogen atom from the pyrimidinyl ring. The 2D fingerprint plots can be deconstructed to focus on particular atom pair contacts. At the top left and bottom right of the fingerprint plot, there are characteristic ‘‘wings’’ which are identified as a result of C…H contacts and O…H interactions are represented by a spike (Fig. 7). The 2D fingerprint plots of the Ni-SDZ molecule, SDZ, and 3-methyl pyridine shows a variety of contacts (H…H, C…H, O…H and N…H) in the crystal structure. The percentages contributions of H…H (37%) of SDZ is higher than Ni-SDZ and 3-methyl pyridine and the contribution C…H (20.4%) of 3-methyl pyridine is higher than Ni-SDZ molecule (18.4%) and SDZ (17.2%). The Hirshfeld surfaces certainly allow a detailed analysis by displaying all the intermolecular interactions within the Ni-SDZ molecule, SDZ, and 3-methyl pyridine77,79.

Figure 5.

Hirshfeld surfaces of Ni-SDZ molecule showing shape index, curvedness, di, and de surface property.

Figure 6.

Hirshfeld surface is visualizing dnorm surface and the column chart shows the percentage contributions of various contacts of molecule Ni-SDZ molecule, SDZ, and 3-methyl pyridine (Solvent).

Figure 7.

2-D fingerprint plot of Ni-SDZ molecule, SDZ and 3-methyl pyridine (Solvent).

Computational analysis

Optimized geometry

An optimized molecular structure of the Ni-SDZ is calculated at B3LYP/LAV2P level by using the Jaguar program in Schrödinger software80. The experimental data are in a crystalline state whereas the Computational data are in a gaseous state. Optimized bond lengths and bond angles are listed in Table 2 and correlation coefficient values for molecular geometry (bond length and bond angle) are 0.982 and 0.989 respectively and the results are represented graphically (Figure S 4).

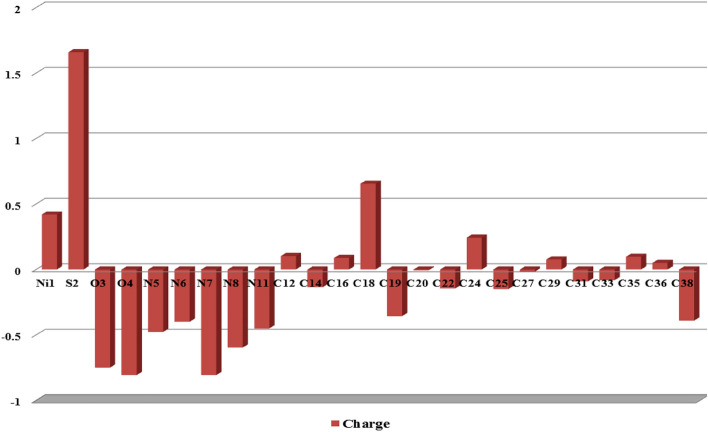

Mullikan population analysis (MPA)

Mullikan population analysis (MPA)46 of the Ni-SDZ is performed at B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level to obtain the values of the atomic charges. The bonding capability of a molecule depends on the electronic charge of the atoms. The calculated Mulliken charge values are listed in Table S1 and represented graphical forms of our results were shown in Fig. 8. The investigation expresses that the atom N7 shows the largest electro negativity (− 0.80577) and S2 shows the largest electro positivity (1.65838) which indicates the large charge delocalization in Ni-SDZ and the positive charges are localized due to hydrogen atoms. The analysis shows the presence of large electronegative atoms O3 (− 0.74922) and O4 (− 0.80557) creates a more positive charge on S2 (1.65838) atom. In the phenyl ring, all the carbon atoms have negative charges except C24 (0.2426). This suggests that atom C24 is acting as the center for charge transfer between the NH2 substituent and the phenyl ring81.

Figure 8.

Histogram for Mulliken atomic charges of Ni-SDZ molecule.

HOMO–LUMO energy

Homo and Lumo energy calculated by B3LYP/LAV2P* method is depicted in Fig. 9 Homo (− 5.407 eV) and Lumo (− 1.279 eV) energy represents an ability to donate and accept the electron. The electronic absorption agrees with the transition from the ground to the first excited state which is largely described by one electron excitation from the highest occupied molecular orbital to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital46,82. The wide energy difference between Homo and Lumo points towards the stability of the molecules and this energy gap (4.128 eV) reflects the chemical activity of the molecule. The UV–Vis spectra report the absorption maxima (265 nm) and optical energy band gap (4.683 eV). The energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO orbital has been found 4.128 eV as calculated theoretically. The computational (HOMO–LUMO) and experimental (UV–Vis) energy gap is measured in different conditions of the environment, therefore smaller deviation has been observed in it78.

Figure 9.

Homo–Lumo energy of Ni-SDZ Molecule.

By using Homo and Lumo energy values of a molecule, the global chemical reactivity descriptor of molecules such as Electronegativity (χ), global hardness (η), global softness (S), and electrophilicity (ω) are calculated using Koopman’s theorem83. Electronegativity (3.343 eV) is a chemical property that describes the ability of an atom to attract electrons or electron density toward itself. The Global hardness (2.064 eV) is a measure of the resistance of an atom to charge transfer, which indicates the molecule is more reactive and less stable. The global softness (0.4845 eV) which is equal to the reciprocal of global hardness describes the capacity of an atom or a functional group to attract electrons. The quantity global electrophilic power of the compound is electrophilicity (2.7205 eV) which defines a quantitative classification of the global electrophilic nature of a compound and measure of energy lowering due to maximal electron flow between donor and acceptor84.

Natural bond orbital analysis (NBO)

Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis is useful to investigate the stability of the molecule (Ni-SDZ) arising from charge delocalization. NBO analysis provides an essential method for understanding the interaction among bonds that played a vital role in the stabilization of the molecule. The second-order Fock matrix has been carried out to evaluate the donor–acceptor interactions in the NBO analysis. E(2) which represents the stabilization energy associated with i(donor)–j(acceptor) delocalization is estimated from the second-order perturbation approach. For each donor NBO (L) and acceptor NBO (NL), the stabilization energy E(2) associated with delocalization is given as:

where ql is the donor orbital occupancy, E(NL) and E(L) are diagonal elements (orbital energies) and F(L, NL) is the off-diagonal NBO Fock matrix element. The higher value of E(2) shows the more intense the interaction between electron donors and electron acceptors46. The LP(2) N7(donor), LV(1) C18(acceptor) interactions have the highest E(2) value of 131.55 kcal/mol. The donor and acceptor orbitals played the most dominant role in stabilizing the molecule (Table 3). The charge transfer interaction has been formed by the orbital overlap between bonding and antibonding orbital. The types of charge transfer in molecules are found to be n → σ ∗ , n → π ∗ and π → π ∗ . The co-ordination covalent bond of non-lewis nickel(acceptor) with lewis type of one 3-methyl pyridine (solvent) nitrogen and two sulfonamide nitrogen (Ni–N) have the E(2) values of 17.65, 7.08, and 16.57 kcal/mol respectively.

Table 3.

Second-order perturbation theory analysis of Fock matrix in NBO basis for Ni-SDZ molecule.

| Donor (L) NBO | Acceptor (NL) NBO | E(2) kcal/mol | E(NL)–E(L) a.u |

|---|---|---|---|

| LP (1) N5 | LV (6) Ni1 | 17.65 | 0.6 |

| LP (2) O3 | σ* S2–C19 | 7.68 | 0.45 |

| LP (3) O3 | σ* S2–O4 | 8.98 | 0.5 |

| LP (3) O3 | σ* S2–N7 | 6.94 | 0.41 |

| LP (2) O4 | σ* S2–C19 | 6.26 | 0.45 |

| LP (3) O4 | σ* S2–O3 | 9.18 | 0.51 |

| LP (1) N6 | σ* N5–C18 | 7.08 | 0.79 |

| LP (2) N7 | LV (1) C18 | 131.55 | 0.09 |

| LP (1) N8 | π* C22–C24 | 16.57 | 0.32 |

| LP (1) C14 | π*N5–C12 | 84.02 | 0.11 |

| LP (1) C14 | π*N6–C16 | 71.37 | 0.13 |

| π N5–C12 | LV (1) C18 | 32.72 | 0.2 |

| π N6–C16 | LV (1) C18 | 44.31 | 0.18 |

| π C19–C20 | π* C22–C24 | 7.77 | 0.28 |

| π C19–C20 | π*C25–C27 | 12.15 | 0.29 |

| π C22–C24 | π* C19–C20 | 14.47 | 0.27 |

| π C22–C24 | π* C 25–C27 | 7.68 | 0.29 |

| π C25–C27 | π* C19–C20 | 8.4 | 0.27 |

| π C25–C27 | π* C22–C24 | 12.69 | 0.27 |

| LP (1) N11 | LV (6)Ni1 | 20.36 | 0.62 |

| π N11–C 29 | π* C35–C36 | 11.38 | 0.35 |

| π C 31–C 33 | π*N11–C29 | 16.48 | 0.24 |

| π C 31–C 33 | π*C35–C36 | 8.61 | 0.3 |

| π C 35–C 36 | π* N11–C29 | 9.46 | 0.23 |

| π C 35–C 36 | π* C31–C33 | 12.36 | 0.27 |

ADMET-SAR parameters

The Caco-2 cellular permeability of the chemical was predicted by the absorption (A) study to be medium. The results in Table 4 indicate that the compound's capability to bind to plasma proteins was modest. Usually, P-glycoprotein binders facilitate the excretion of chemicals from the cells through the drug efflux mechanism and increase drug resistance. The results revealed that the compound was neither a substrate nor an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein. Human Intestinal Absorbance data revealed that the compound has the potential to be well absorbed. The compound has lower MDCK permeability. Drug distribution (D) analysis predicted to the compound cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). In the analysis of liver microsomal metabolism, the 2 key cytochrome P450s (CYP450s) which are involved in drug metabolism are CYP2D6 and CYP3A4; these two enzymes together perform the majority of the liver microsomal phase-I drug metabolism. The results showed that the compound was an inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4; not a substrate for CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Toxicity parameters of the compound reflected that it has a medium risk for hERG inhibition85.

Table 4.

Computational studies of a molecule.

| ADMET parameters | |||

| BBB | 0.0355242 | Skin permeability | − 4.15228 |

| Caco2 | 17.8992 | CYP 2C19 inhibition | Non |

| HIA | 94.384107 | CYP_2C9 inhibition | Non |

| MDCK | 0.518548 | CYP_2D6 inhibition | Inhibitor |

| Pgp inhibition | Non | CYP 3A4 inhibition | Inhibitor |

| Plasma Protein Binding | 48.744991 | hERG inhibition | Medium risk |

BBB = blood–brain barrier (high absorption CNS > 2.0, middle absorption CNS 2.0–0.1, low absorption to CNS < 0.1, Caco2 (high permeability > 70, middle permeability 4–70, low permeability < 4, %HIA (human intestinal absorbance) (well-absorbed compounds 70–100%, moderately absorbed compounds 20%–70%, poorly absorbed compounds 0–20%), %PPB (plasma protein binding) (strongly bound > 90%, weakly bound < 90%), MDCK (higher permeability > 500, medium permeability 25–500, lower permeability < 25).

CT-DNA interaction studies

Polycyclic aromatic molecules can interact with DNA either through forming covalent bonding with DNA or by some non-covalent interaction like groove binding, electrostatic interaction, and intercalation. In groove binding, the molecules locate themselves in the major or minor groove of the DNA, and forces like hydrogen bonding, van der Waals, or hydrophobic interaction stabilizes the molecule-DNA conformation. Intercalation occurs when molecules of a reasonable size and chemical nature fit in between the stacks of DNA base pairs through associative π-stacking interaction and these often make a good nucleic acid stain86. Some intensively studied DNA intercalators are ethidium bromide, daunomycin, doxorubicin, etc. Doxorubicin and daunorubicin are used in the treatment of some tumors. DNA interaction study is very useful in developing a novel class of antitumor agents. UV–visible absorption spectroscopy and relative viscosity measurement studies were used to determine the binding ability of Ni-complex with DNA. The measurement of change in electronic spectra of the metal complex upon successive addition of DNA gives valuable information about the binding mode and strength. The effect of the stoichiometric addition of calf thymus DNA on the UV–visible absorption spectra of Ni-complex is shown in Fig. 10. The increase in the concentration of CT DNA resulted in a hypochromic with bathochromic shift, which suggests that the complex interacts with DNA most likely through a mode that involves a stacking interaction between the aromatic chromophore and the base pairs of DNA. The columbic force between metal ions and the phosphate of nucleotide could favor these interactions. Using absorption titration measurements, a linear plot of [DNA]/(εf − εa) versus [DNA] (Fig. 10, inset) is obtained. Assuming all the molecules of complexes were bound with DNA, the experimental Kb was obtained by substituting the absorbance into Beer’s law. The Kb value derived from the plot for the complex is 3.8 × 104 M-1. The bathochromic shift, hypochromic, and large binding constant value obtained for Ni-complex suggests that the binding mode is intercalation21,87–91.

Figure 10.

Absorption spectra of complex with increasing amount of CT-DNA in Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.2)19. = 5 µM, [DNA] = 0–60 µM with an incubation period of 10 min at room temperature.

The change in relative viscosity of DNA with increasing concentration of any compound is directly associated with the mode of interaction. The intercalation of compounds in between the base pair stacks lengthens the DNA size, and so the viscosity of the DNA solution increases. While the partial intercalation or non-classical interactions can bend the DNA, and hence the size of the DNA chain is reduced and so is the viscosity. So, the relative viscosity measurement results are the least ambiguous in finding the mode of interaction between DNA. The relative viscosity of the DNA solution increases with an increase in the concentration of Ni-complex, which is the result of an increase in the size of the DNA chain due to intercalation (Figure S5). Similar kinds of results are observed in the case of reported metal complexes and classical intercalator, EtBr and the data are supporting the UV–visible absorption titration study55,87,88,92.

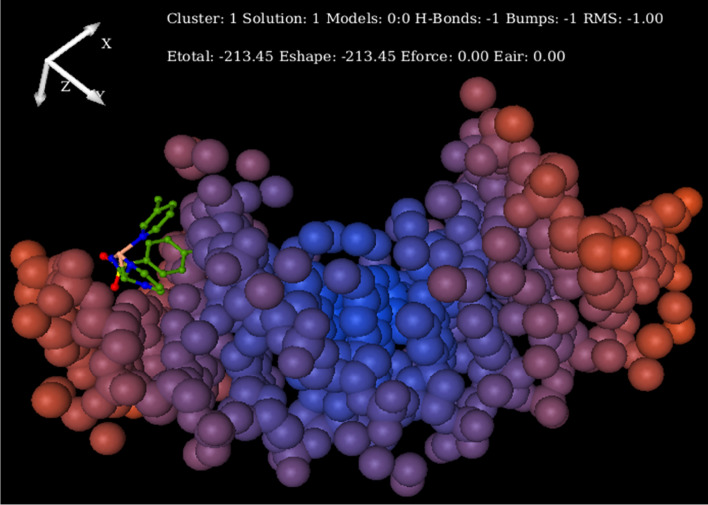

Molecular docking study

Molecular docking is used to predict the structure of intermolecular complexes formed between two or more constituent molecules. Currently, it is actively used in virtual screening, lead optimization, biological activity prediction, binding site identification, drug-biomolecular interaction, etc. So, it has gained enormous interest for researchers as a tool for drug discovery, nowadays. The computational strategy allows for permeating all aspects of drug discovery today. Our interest to find out the primary site of interaction of Ni-complex with DNA was accomplished by molecular docking studies on DNA duplex of self-complementary sequenced (ACCGACGTCGGT)2 by Hex software 8.1. The final binding orientation among all possible conformation having optimal energy is considered as a docked pose with minimum energy, which shows that minor groove mode plays a predominant role in the interaction (Fig. 11)45,93–95. The relative binding energy of the docked structure was found − 213.45 kJ mol−1. The lower binding energy implies a more potent binding affinity between the receptor (DNA) and a metal complex. These data are consistent with the UV–visible absorption titration study and relative viscosity measurement.

Figure 11.

Molecular docked model of a complex located within the hydrophobic pocket of DNA (PDB ID: 1BNA).

Cytotoxicity and cell viability studies

Cytotoxicity is the most important study among all biological evaluation studies. The compound may have different cytotoxicity mechanisms such as cell membrane destruction, prevention of protein synthesis, irreversible receptor binding, etc. So, the determination of cell death requires cheap, reliable, and reproducible short-term cytotoxicity and cell viability assays, for which a broad spectrum of cytotoxicity assays are currently used. The brine shrimp lethality assay correlates reasonably well with cytotoxic and anti-tumor properties. In the present study, the brine shrimp lethality of the metal complex was determined using the procedure of Meyer et al. The maximum mortality of brine shrimp was observed at a 30 µM concentration of Ni-complex. The LC50 value of the metal complex was obtained by a plot of the percentage of the shrimp nauplii killed against the concentrations of the metal complex and the best-fit line was obtained from the data using regression analysis. This significant lethality of the metal complex (LC50 = 7.44 µM) to brine shrimp is indicative of the presence of potent cytotoxic components which warrants further investigation.

The proportion of viable cells in a cell population was estimated by the simplest and most widely used dye exclusion method. In the dye exclusion method, viable cells exclude dyes, but dead cells do not exclude them. In vivo, cytotoxic study of Ni(II) complex at a cellular level was carried out using eukaryotic S. pombe cell by trypan blue assay. The percentage viability of cells treated by complex after 17 h treatment is 92%, 87%, 81%, 79%, and 74%, for series of complex concentrations 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 µg/mL, respectively. The data clearly shows the potent cytotoxic nature of the complex.

Photo-catalytic degradation

The photocatalytic degradation of MB was conducted to investigate the efficiency of photocatalysts. The photocatalytic activities of Ni-SDZ were monitored from the variation of the color in the reaction system by measuring the maximum absorbance intensity of MB. The absorption spectra of a sample (20 min time interval) and MB is shown in Fig. 12a. The absorption spectra of the MB solution decreased with visible light irradiation time. Under visible irradiation in a period of 70 min, the Ni-SDZ complex can degrade over 70.19% of the MB dye (Fig. 12a). The reduction in the intensity of the maximum absorption peak (662 nm) for MB suggests the complete removal of the chromophoric group within the MB molecule (Fig. 12a). If the position of the distinctive peak in the MB absorption spectrum, centered at 662 nm, remains unchanged throughout the experiment despite the diminishing intensity, this signifies the nonexistence of any other chromophore molecules produced as by-products. The complete degradation of MB without any intermediate formation can be examined by the disappearance of the λmax peak (662 nm) without the appearance of other peaks in the UV–vis spectra96. At the same time, the photograph of the MB dye degrading sample with time clearly shows the color change of MB dye. The photocatalytic degradation activity of Ni-SDZ complex is more than reported [Co(4,4′‐bipy)∙(HCOO)2]n (54.70% degradation) MOF complex97. The curve of changes in the relative concentration of MB dye (calculated from the absorption data) versus visible light irradiation time for each sample is demonstrated in Fig. 12b and the logarithms of the values are shown in Fig. 12c. To have a better understanding of the reaction kinetics of the MB degradation catalyzed by Ni-SDZ photocatalysts, the experimental data were fitted by a first‐order model as expressed by Eq. (1) (Langmuir‐Hinshelwood model) since the value of the rate constant k commonly indicates the activity of the photocatalyst. The degradation pathway starts with electronic reorganization, the sulfhydryl group (C–S+=C) transforms a sulfoxide (C–S=O)–C), leading to the opening of the central aromatic heterocycle. The introduction of an electrophilic.OH group at the unpaired electron of the S heteroatom results in a change of its oxidation state from − 2 to 0. However, the transition from C–S+.C to C–S(.O)–C must maintain the preservation of the double bond conjugation, which in turn triggers the unfolding of the central aromatic ring that encompasses both heteroatoms (S and N). The necessary hydrogen atoms for the formation of C–H and N–H bonds may be derived from the reduction of protons due to electrons generated by light. Among the intermediate byproducts observed in the degradation of MB are 2-amino-5-(N-methyl formamide) benzene sulfonic acid, 2-amino-5-(methyl amino)-hydroxybenzene sulfonic acid, benzenesulfonic acid, and phenol (Fig. 12e).

| 1 |

where C0 and C is the initial and apparent concentration of the MB and k is the kinetic rate constant. The values of k were obtained from the slope and the intercept of the linear plot. Figure 12d shows a linear relationship between ln(C/C0) and the irradiation time for MB degradation. The rate constants for MB photodegradation with Ni-SDZ under visible light are − 0.01634 min−1. The values of k indicated that the activity of photocatalyst Ni-SDZ is better than that of reported data58,91,98–100.

Figure 12.

(a) Absorption spectra of MB solution with Ni-SDZ complex function of visible light irradiation time, (b) Photocatalytic degradation rate of MB in the presence of Ni-SDZ complex, (c) The liner fitting of -in C/Co and irradiation time and (d) Starting and final degradation % V/S time and (e) Degradation pathway of MB dye via Chromophoric group degradation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Ni(II) complex of sulfadiazine has been successfully synthesized. The magnetic measurements (EPR and magnetic susceptibility) data reveal the complex coordination is distorted octahedral. By crystal data results, the sulfadiazine ligand is bidentate and the geometry of the Ni-SDZ molecule is suggested to be octahedral, involving two nitrogen atoms of the sulfonamide group and two nitrogen atoms from the 3-methyl pyridine ligand. The experimental results were complemented with DFT calculations showing a good agreement between calculated and experimental geometrical parameters. The NBO analysis reveals that the intra-molecular interaction orbital overlaps providing the maximum stability to the molecule. Hirshfeld surface analysis reveals intermolecular O···H and H···H contacts are the most significant interactions in the crystal. The DNA interaction studies as performed using relative viscosity measurement and UV–visible absorption titration suggest intercalation of the complex in between the stacks of DNA base pairs. The molecular docking study suggests the minor groove as the first site of interaction of complex for DNA followed by intercalation. The cytotoxic and cell viability analysis of the complex suggests the potent cytotoxic nature of the complex. The molecular docking study complemented the DNA binding studies of the complex. The percentage of degradation of methylene blue dye was found to be 70.19% within 70 min of visible light radiation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Physics, Sardar Patel University, India for making it convenient to work in the laboratory. We are thankful to DST-FIST, New Delhi for funding the single crystal diffractometer facility at the Department of Physics, Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Anand, Gujarat, India. Bhavesh N. Socha is thankful to UGC CPEPA-II/2018-19/2442(11) programme of P.G. Department of Chemistry, Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, for project fellowship. We also acknowledge the help received from the Department of Chemistry, Sardar Patel University for DNA binding study, and SAIF, IIT Bombay for EPR analysis.

Author contributions

S.B.P.: Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft. B.N.S.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Photocatalyst activity. U.H.P.: Conceptualization, Editing, Supervision, Methodology. R.P.D.: Data curation, Software, Formal analysis. R.H.P.: Supervision, Formal analysis. B.S.B.: DNA interactions studies. P.T.: Anticancer activity, Formal analysis. S.B.: Photocatalyst activity. N.V.: Photocatalyst activity. J.V.: Photocatalyst activity, Formal analysis.

Data availability

We would like to confirm that all relevant data and materials supporting the findings of our journal paper are available upon request. For data inquiries, please contact Bhavesh Socha at bhaveshkumarsocha@gmail.com.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sachin B. Pandya, Email: sachinpandya561@gmail.com

Bhavesh N. Socha, Email: bhaveshkumarsocha@gmail.com

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-42668-z.

References

- 1.Aljohani ET, Shehata MR, Abu-Dief AM. Design, synthesis, structural inspection of Pd2+, VO2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+ chelates incorporating ferrocenyl thiophenol ligand: DNA interaction and pharmaceutical studies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021;35(4):e6169. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aljohani ET, et al. Development and structure elucidation of new VO2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, and Pd2+ complexes based on azomethine ferrocenyl ligand: DNA interaction, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer activities, and molecular docking. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021;35(5):e6154. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barabadi H, et al. Green synthesis, characterization, antibacterial and biofilm inhibitory activity of silver nanoparticles compared to commercial silver nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021;129:108647. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tačić A, et al. Antimicrobial sulfonamide drugs. Adv. Technol. 2017;6(1):58–71. doi: 10.5937/savteh1701058T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A, et al. Discovery of HIV-1 protease inhibitors with picomolar affinities incorporating N-aryl-oxazolidinone-5-carboxamides as novel P2 ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49(25):7342–7356. doi: 10.1021/jm060666p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarroll AJ, et al. Quinols As novel therapeutic agents. 7. Synthesis of antitumor 4-[1-(arylsulfonyl-1 H-indol-2-yl)]-4-hydroxycyclohexa-2, 5-dien-1-ones by Sonogashira reactions. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50(7):1707–1710. doi: 10.1021/jm061163m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson BL, et al. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: inhibition of isozymes I, II, and IX with triazole-linked O-glycosides of benzene sulfonamides. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50(7):1651–1657. doi: 10.1021/jm061320h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drews J. Drug discovery: A historical perspective. Science. 2000;287(5460):1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd AE. Sulfonylurea receptors, ion channels, and fruit flies. Diabetes. 1988;37(7):847–850. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Supuran CT, Scozzafava A. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2000;10(5):575–600. doi: 10.1517/13543776.10.5.575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadi AA, et al. Synthesis, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities of novel 2-(1-adamantyl)-5-substituted-1, 3, 4-oxadiazoles and 2-(1-adamantylamino)-5-substituted-1, 3, 4-thiadiazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007;42(2):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenone S, et al. New 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole derivatives endowed with analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14(6):1698–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghorab MM, et al. Anticancer and radio-sensitizing evaluation of some new thiazolopyrane and thiazolopyranopyrimidine derivatives bearing a sulfonamide moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46(10):5120–5126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liou J-P, et al. A novel oral indoline-sulfonamide agent, N-[1-(4-methoxybenzenesulfonyl)-2, 3-dihydro-1H-indol-7-yl]-isonicotinamide (J30), exhibits potent activity against human cancer cells in vitro and in vivo through the disruption of microtubule. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;323(1):398–405. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.126680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornber C. Isosterism and molecular modification in drug design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1979;8(4):563–580. doi: 10.1039/cs9790800563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrases: Novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7(2):168. doi: 10.1038/nrd2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajapakse S, et al. Antibiotics for human toxoplasmosis: A systematic review of randomized trials. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2013;107(4):162–169. doi: 10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tung, A. S., Toxoplasmosis and the associated retinochoroiditis: important facts and when to treat.

- 19.Elkanzi, N., et al., Synthesis, characterization, 3D modeling, and in vitro antibacterial, and antifungal activity evaluation of novel Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes based on 2-[(4-{[(4-methylphenyl) sulfonothioyl] oxy} phenyl) methylene] amino} benzoic acid.

- 20.Aljohani FS, et al. Structural inspection for novel Pd(II), VO(II), Zn(II) and Cr(III)-azomethine metal chelates: DNA interaction, biological screening and theoretical treatments. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1246:131139. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abu-Dief AM, et al. Tailoring, structural elucidation, DFT calculation, DNA interaction and pharmaceutical applications of some aryl hydrazone Mn(II), Cu(II) and Fe(III) complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1244:131017. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abu-Dief AM, El-Sagher HM, Shehata MR. Fabrication, spectroscopic characterization, calf thymus DNA binding investigation, antioxidant and anticancer activities of some antibiotic azomethine Cu(II), Pd(II), Zn(II) and Cr(III) complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33(8):e4943. doi: 10.1002/aoc.4943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Giménez JL, et al. Toward the development of metal-based synthetic nucleases: DNA binding and oxidative DNA cleavage of a mixed copper(II) complex with N-(9H-purin-6-yl) benzenesulfonamide and 1, 10-phenantroline. Antitumor activity in human Caco-2 cells and Jurkat T lymphocytes. Evaluation of p53 and Bcl-2 proteins in the apoptotic mechanism. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103(6):923–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casanova J, et al. Metal complexes of sulfanilamide derivatives. Crystal structure of [Zn (sulfathiazole)2]· H2O. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1993;51(4):689–699. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(93)85001-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chohan ZH, et al. In-vitro antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic properties of sulfonamide—Derived Schiff's bases and their metal complexes. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2005;20(2):183–188. doi: 10.1080/14756360500043257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel MN, Bhatt BS, Dosi PA. Spectroscopic study of DNA hydrolysis, DNA intercalative, and electrostatic interaction activity exerted by drug based coordination compounds. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2012;638(1):152–162. doi: 10.1002/zaac.201100307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kremer E, et al. Copper complexes with heterocyclic sulfonamides: Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, microbiological and SOD-like activities: Crystal structure of [Cu (sulfisoxazole)2(H2O)4]· 2H2O. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100(7):1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casanova J, et al. Coordination behavior of sulfathiazole. Crystal structure of dichloro-disulfathiazole ethanol Cu(II) complex. Superoxide dismutase activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1994;56(2):65–76. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(94)85038-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baenziger N, Struss AW. Crystal structure of 2-sulfanilamidopyrimidinesilver (I) Inorg. Chem. 1976;15(8):1807–1809. doi: 10.1021/ic50162a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook DS, Turner MF. Crystal and molecular structure of silver sulphadiazine (N1-pyrimidin-2-ylsulphanilamide) J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2. 1975;10:1021–1025. doi: 10.1039/p29750001021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baenziger N, Modak S, Fox C. Diamminebis (2-sulfanilamidopyrimidinato) zinc(II), [Zn(C10H9N4O2S)2(NH3)2] Acta Crystallogr. C. 1983;39(12):1620–1623. doi: 10.1107/S0108270183009506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha M, et al. Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) ternary complexes with sulfadiazine and dimethylformamide: Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, crystallographic study and antibacterial activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1176:605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erkkila KE, Odom DT, Barton JK. Recognition and reaction of metallointercalators with DNA. Chem. Rev. 1999;99(9):2777–2796. doi: 10.1021/cr9804341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metcalfe C, Thomas JA. Kinetically inert transition metal complexes that reversibly bind to DNA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003;32(4):215–224. doi: 10.1039/b201945k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakthi M, Ramu A. Synthesis, structure, DNA/BSA binding and antibacterial studies of NNO tridentate Schiff base metal complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1149:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.08.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallikarjuna N, Keshavayya J, Ravi B. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial, antitubercular and DNA cleavage studies of 2-(1H-indol-3-yldiazenyl)-4, 5, 6, 7-tetrahydro-1, 3-benzothiazole and its metal complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1173:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asadi Z, Nasrollahi N. The effect of metal and substituent on DNA binding, cleavage activity, and cytotoxicity of new synthesized Schiff base ligands and Zn(II) complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1147:582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.06.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vekariya PA, et al. Half sandwich Rhodium(III) and Iridium(III) complexes as cytotoxic and metallonuclease agents. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12010-018-2835-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blessing RH. An empirical correction for absorption anisotropy. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1995;51(1):33–38. doi: 10.1107/S0108767394005726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2008;64(1):112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrugia LJ. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012;45(4):849–854. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812029111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burnett, M. N. & Johnson, C. K. ORTEPIII. Report ORNL-6895. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Tennessee, USA (1996).

- 43.Wolff, S., et al. CrystalExplorer (Version 3.1); University of Western Australia: 2012. There is no corresponding record for this reference.(b) Spackman, MA; Jayatilaka, D. CrystEngComm11(1), 19–32 (2009).

- 44.Spackman MA, Jayatilaka D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm. 2009;11(1):19–32. doi: 10.1039/B818330A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chavda BR, et al. Coordination behavior of dinuclear silver complex of sulfamethoxazole with solvent molecule having static rotational disorder: Spectroscopic characterization, crystal structure. Hirshfeld Surf. Antimicrob. Act. 2021;1228:129777. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dubey RP, Patel UH, Patel BD. Study on molecular structure, spectral investigations, NBO, NLO, Hirshfeld surface analysis and Homo-Lumo energy of silver complex of 4-Amino-N-(2, 6-dimethoxypyrimidin-4-yl) benzenesulfonamide. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2018;48(2):110–119. doi: 10.1080/24701556.2017.1357635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubey RP, Patel UH, Tailor SM. DFT studies, Hirshfeld surface analysis and crystal structure of novel silver complex of sulfapyridine with secondary ligand pyridine. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2017;656(1):139–152. doi: 10.1080/15421406.2017.1397432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel KD, Patel UH. Quantitative analysis of weak interactions by Lattice energy calculation, Hirshfeld surface and DFT studies of sulfamonomethoxine. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1128:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.08.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demir S, et al. Vibrational spectroscopic studies, NMR, HOMO–LUMO, NLO and NBO analysis of 1-(2-nitrobenzoyl)-3, 5-diphenyl-4, 5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole with use X-ray diffractions and DFT calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2016;1108:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.12.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lalvani KK, et al. Synthesis, crystallographic investigation, DFT studies and Hirshfeld surface analysis of novel bromo hydrazine derivative: (E)-2-(2-bromo-4, 5-dimethoxybenzilidene)-1-(4, 5-dimethoxy-2-methylphenyl)-1-hydroxyhydrazine. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2022;732(1):87–101. doi: 10.1080/15421406.2021.1989652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Namera DL, et al. Arylidene analogues as selective COX-2 inhibitors: synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39(18):7150–7159. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1806109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kallus S, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of biotin-conjugated anticancer thiosemicarbazones and their iron(III) and copper(II) complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019;190:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shahabadi N, Moghadam NH. DNA interaction studies of a platinum(II) complex containing an antiviral drug, ribavirin: The effect of metal on DNA binding. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012;96:723–728. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel MN, Bhatt BS, Dosi PA. Topoisomerase inhibition, nucleolytic and electrolytic contribution on DNA binding activity exerted by biological active analogue of coordination compounds. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012;166(8):1949–1968. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9623-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Padariya TJ, et al. Synthesis, physicochemical, quantitative analysis and crystal structures of two mononuclear diperchlorate cobalt(II) complexes of 1, 10-phenanthroline: antimicrobial, cytotoxicity and DNA/BSA interaction studies. Struct. Chem. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11224-022-02093-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alalawy MD, et al. Role of secondary ligand on Cd complex of sulfamethizole: Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, Hirshfeld surface analysis and DNA interaction. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1247:131411. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pandya SB, et al. DNA interaction, cytotoxicity and molecular structure of cobalt complex of 4-amino-N-(6-chloropyridazin-3-yl) benzene sulfonamide in the presence of secondary ligand pyridine. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33(12):e5235. doi: 10.1002/aoc.5235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Socha BN, et al. 1-D MOF [Ag2(C10H10N3O3S)2(C4H8N)2]n: Photocatalytic treatment, crystallographic evaluation, ADMET parameters, CT-DNA and anticancer activity. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2236732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanthecha DN, et al. Biological significance of hetero-scaffolds based gold(III) complexes. Acta Chim. Slov. 2018;65(2):333–343. doi: 10.17344/acsi.2017.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pandya SB, et al. DNA interaction, cytotoxicity and molecular structure of cobalt complex of 4-amino-N-(6-chloropyridazin-3-yl) benzene sulfonamide in the presence of secondary ligand pyridine. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:e5235. doi: 10.1002/aoc.5235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thakor P, et al. Extraction and purification of phytol from Abutilon indicum: Cytotoxic and apoptotic activity. RSC Adv. 2016;6(54):48336–48345. doi: 10.1039/C5RA24464A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shin HS, et al. The crystal and molecular structure of sulfadiazine. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1974;18(5):329–340. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh T, Patel U, Haridas M. Structure of 2-[4-(acetylaminosulphonyl) phenylcarbamoyl] benzoic acid (phthalylsulfacetamide), C16H14N2O6S. Acta Crystallogr. C. 1984;40(12):2088–2091. doi: 10.1107/S010827018401074X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tailor SM, Patel UH. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial activity and crystal structure of [Ag2(C10H10N3O3S)2(C5H5N)3] J. Mol. Struct. 2015;1088:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y-F, et al. trans-Bis [4-amino-N-(pyrimidin-2-yl) benzenesulfonamidato] dipyridinenickel(II) hemihydrate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online. 2009;65(12):m1584–m1584. doi: 10.1107/S1600536809043621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mondelli M, et al. Study of a series of cobalt(II) sulfonamide complexes: Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and microbiological evaluation against M. tuberculosis. Crystal structure of [Co (sulfamethoxazole)2(H2O)2]· H2O. J. Mol. Struct. 2013;1036:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.09.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O-T, W. K. Nakanishi, Infrared absorption spectroscopy---practical. Holden-Day, Inc., San Francisco, 1962, pp. 233. Price $9.85.J. Mol. Struct.5, 244–244 (1970).

- 68.Macias B, et al. Synthesis and characterization of sulfonamides containing 8-aminoquinoline and their Ni(II) complexes. Crystalline structures of the Ni complexes. Polyhedron. 2002;21(12–13):1229–1234. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(02)00997-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blasco F, et al. Cobalt(II), Nickel(II), and Copper(II) complexes of sulfanilamide derivatives: Synthesis, spectroscopic studies, and antibacterial activity. Crystal structure of [Co(sulfacetamide)2(NCS)2] J. Inorg. Biochem. 1996;61(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(95)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Driessen W, Van der Voort P. Metal(II) isoxazole complexes: Spin crossover in the iron(II) compounds. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1977;21:217–222. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)86264-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Casanova J, et al. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Synthesis of water-soluble, topically effective, intraocular pressure-lowering aromatic/heterocyclic sulfonamides containing cationic or anionic moieties: is the tail more important than the ring. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1993;51:689–761. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(93)85001-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tailor SM, Patel UH. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial activity and crystal structure of silver and copper complexes of sulfamethazine. J. Coord. Chem. 2015;68(13):2192–2207. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2015.1055258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hosny NM, et al. Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity of new 2-isonicotinoyl-N-phenylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide and its metal complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:e4998. doi: 10.1002/aoc.4998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdel-Rhman MH, et al. Synthesis, characterization, molecular docking and cytotoxicity studies on N-benzyl-2-isonicotinoylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide and its metal complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1196:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.06.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Figgis B, Nyholm R. A convenient solid for calibration of the Gouy magnetic susceptibility apparatus. J. Chem. Soc. 1958;4:4190–4191. doi: 10.1039/JR9580004190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKinnon JJ, Jayatilaka D, Spackman MA. Towards quantitative analysis of intermolecular interactions with Hirshfeld surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2007;37:3814–3816. doi: 10.1039/b704980c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dubey RP, et al. Cadmium complex of sulfathiazole dihydrate with secondary ligand pyridine: Structure, DFT studies, Hirshfeld surface analysis and antimicrobial activity. Indian J. Phys. 2021;95:33–42. doi: 10.1007/s12648-019-01680-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Socha BN, et al. Structural investigation, quantum chemical calculation, energy framework analysis and MIC studies of silver and cobalt complexes of 4-amino-N-(4, 6-dimethyl-2 pyrimidinyl) benzenesulfonamide in presence of secondary ligand. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alalawy MD, et al. Qualitative and quantitative contributions of intermolecular interactions of dinuclear Ag complexes of sulfathiazole and sulfadiazine: X-ray crystallographic, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT studies and biological activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1255:132426. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bochevarov AD, et al. Jaguar: A high-performance quantum chemistry software program with strengths in life and materials sciences. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013;113(18):2110–2142. doi: 10.1002/qua.24481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel MK, et al. Crystal structure elucidation, Hirshfeld surface analysis, lattice energy frame work, and molecular docking studies of copper(II) complex of 1-(3-bromo-5-chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl) ethan-1-one in the presence of solvent pyridine as secondary ligand. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2022 doi: 10.1080/24701556.2022.2078353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dodeja KK, et al. Lipophilicity, gas-phase optimized geometry, quantum chemical calculations, Hirshfeld surface analysis, energy frameworks, and molecular docking studies of novel (Z)-2-((3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl) methylene)-3, 4-dihydronaphthalen-1 (2H)-one. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2021 doi: 10.1080/24701556.2021.1983839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koopmans T. Ordering of wave functions and eigenenergies to the individual electrons of an atom. Physica. 1933;1:104–113. doi: 10.1016/S0031-8914(34)90011-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pandya SB, et al. Combined experimental and computational studies on molecular structure of nickel complex of 4-amino-N-(1, 3-thiazol-2-yl) benzenesulfonamide with coordinated pyridine. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2021;51(9):1280–1290. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thakkar AB, et al. Isolation, identification, and characterization of α-asarone, from hydromethanolic leaf extract of Acorus calamus L. and its apoptosis-inducing mechanism in A549 cells. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2227712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alves CM, et al. Novel long alkyl side chain benzo [a] phenoxazinium chlorides: Synthesis, photophysical behaviour and DNA interaction. Tetrahedron. 2009;65(50):10441–10452. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Akcha S, et al. Copper(II) and nickel(II) complexes derived from a carbothioamide-5-pyrazolone ligand: Synthesis, characterization, crystal structures, electrochemical, potentiometric and DNA-binding studies. J. Coord. Chem. 2015;68(24):4373–4394. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2015.1096932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sureshbabu P, et al. Phosphoester binding, DNA binding, DNA cleavage and in vitro cytotoxicity studies of simple heteroleptic copper(II) complexes with bidentate ligands. J. Coord. Chem. 2018;71(22):3615–3638. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2018.1527029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abu-Dief AM, et al. Fabrication, structural elucidation of some new metal chelates based on N-(1H-Benzoimidazol-2-yl)-guanidine ligand: DNA interaction, pharmaceutical studies and molecular docking approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2023;386:122353. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abu-Dief AM, et al. Synthesis, structural elucidation, DFT calculation, biological studies and DNA interaction of some aryl hydrazone Cr3+, Fe3+, and Cu2+ chelates. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2022;97:107643. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2022.107643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abu-Dief AM, et al. Synthesis and characterization of new Cr(III), Fe(III) and Cu(II) complexes incorporating multi-substituted aryl imidazole ligand: Structural, DFT, DNA binding, and biological implications. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020;228:117700. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Socha BN, et al. Role of metal Cu(II) and Ag(I) on molecular structure of 4-amino-N-(2, 6-dimethoxypyrimidin-4-yl) benzenesulfonamide in presence of 3-methyl pyridine: Synthesis, spectral, crystallographic and DNA interaction studies. Polyhedron. 2020;188:114696. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alalawy MD, et al. Molecular structure investigation, Hirshfeld surface analysis and DNA interaction of cadmium complex of 4-amino-N-(1, 3-thiazol-2-yl) benzenesulfonamide monohydrate in the presence of the secondary ligand β-picoline. Polyhedron. 2021;200:115137. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2021.115137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Socha BN, et al. Gas-phase DFT studies, quantum chemical calculation and 3D energy framework analysis of novel copper complex of sulfadimethoxine in the presence of secondary ligand 3-methyl pyridine. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2021;51(12):1822–1830. doi: 10.1080/24701556.2020.1856140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dubey RP, et al. Quantum chemical calculations, molecular docking, Hirshfeld surface analysis, biological activity, and characterizations (IR and NMR) of cadmium complex of triple sulfa drugs constituent sulfamethazine. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2020;51(10):1442–1451. doi: 10.1080/24701556.2020.1839767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khan I, et al. Review on methylene blue: Its properties, uses, toxicity and photodegradation. Water. 2022;14(2):242. doi: 10.3390/w14020242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang M, et al. Two pure MOF-photocatalysts readily prepared for the degradation of methylene blue dye under visible light. Dalton Trans. 2018;47(12):4251–4258. doi: 10.1039/C8DT00156A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Alzaid M, et al. Novel (Y2O3)x(CdO)1–x binary mixed oxide nanocomposites: Facile synthesis, characterization, and photocatalysis enhancement. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023;23:2454–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.01.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abu-Dief AM, et al. Facile synthesis and characterization of novel Gd2O3–CdO binary mixed oxide nanocomposites of highly photocatalytic activity for wastewater remediation under solar illumination. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2021;148:109666. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mohamed W, Abu-Dief AM. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalysis enhancement of Eu2O3–ZnO mixed oxide nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2018;116:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We would like to confirm that all relevant data and materials supporting the findings of our journal paper are available upon request. For data inquiries, please contact Bhavesh Socha at bhaveshkumarsocha@gmail.com.