Abstract

MA6, an O157:H7-like strain, did not react with most anti-O157 kits examined; however, it had the rfbE gene that is essential for O157 expression and carried O157:H7 virulence factors. Lipopolysaccharide analysis showed that MA6 is a rough strain that does not produce the O157 antigen, but genetically, it belongs in the O157:H7 clonal group.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) of O157:H7 serotype is identified serologically by its somatic O157 and flagellar H7 antigens. In routine clinical analysis, fecal specimens are plated onto sorbitol MacConkey agar and non-sorbitol-fermenting colonies are tested serologically for the O157 antigen. Only isolates that react with anti-O157 serum are serotyped further for the H7 antigen and assayed for virulence factors. Analysis for O157:H7 in foods is done by a similar protocol, except that samples are first enriched in broth medium before plating and testing for the sorbitol phenotype and the O157 antigen (5). Recently, many commercial anti-O157 kits have been introduced, which assay enrichment broths directly for O157:H7 (6). Therefore, testing for the O157 antigen is critical in the isolation and identification of O157:H7 from both clinical and food specimens.

A recent paper reported the isolation of E. coli O157:H7 from beef marketed in Malaysia (13). One of the isolates, MA6, had the typical O157:H7 phenotype, and an initial screening using two latex agglutination kits as well as an O:H serotyping kit showed this strain to be O157:H7. However, when MA6 was tested with another anti-O157 test (QUIX; Universal HealthWatch, Inc., Columbia, Md.), it was found to be negative. This discrepancy in MA6 reactivity to O157-specific antisera was unexpected and therefore was investigated further in this study. We used serological and genetic assays to characterize MA6 and determined that it was a rough strain of O157:H7 that does not make the O157 antigen.

Serological analysis.

The discrepancy in serological reactivity of MA6 could be due to differences in the specificity of O157 antisera; hence, we examined MA6 with other anti-O157 assays. These tests, listed in Table 1, were performed according to the manufacturers’ specifications. Using TT12, an outbreak strain of O157:H7 serotype as the positive control, MA6 was found not to react with most of the anti-O157 kits examined. It did, however, react with anti-H7 sera in the Seiken and RIM kits; hence, it carried the H7 antigen. To resolve this discrepancy regarding its O-antigen type, MA6 was sent for serotyping to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and to the Escherichia coli Reference Center, Pennsylvania State University. Both institutions verified the presence of the H7 antigen; however, O serotyping was inconclusive. The reference center found that MA6 agglutinated with anti-O157 serum, but it also reacted with 14 other O sera.

TABLE 1.

Serological assay kits used in the analysis of E. coli MA6 and TT12 strains

| Target antigen | Kit | Formata | Manufacturer | Reactionb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA6 | TT12 | ||||

| O157 | Stain | FA | KPLc | − | ND |

| RIM | LA | REMEL | − | + | |

| OXOID | LA | Unipath | − | + | |

| Wellcolex | LA | Murex | − | + | |

| Seiken | AG | Denka Seiken | + | + | |

| VIDAS | EIA | bioMerieux | − | + | |

| O157 | EIA | LMD Laboratories | + | ND | |

| VIP | Abppt | BioControl | − | + | |

| Reveal | Abppt | Neogen | − | + | |

| QUIX | Abppt | Universal Health Watch | − | ND | |

| H7 | RIM | LA | REMEL | + | + |

| Seiken | AG | Denka Seiken | + | ND | |

| Stx1 | Verotox-F | RPLA | Denka Seiken | − | + |

| Stx2 | Verotox-F | RPLA | Denka Seiken | + | + |

Abbreviations: FA, fluorescent antibody (12); LA, latex agglutination; AG, agglutination; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; Abppt, immunoprecipitation; RPLA, reverse passive latex agglutination.

−, no reaction; +, reaction; ND, not done.

KPL, Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories.

Genetic analysis.

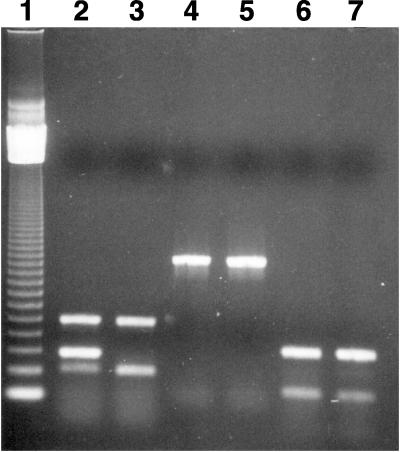

Since the O antigen of strain MA6 could not be determined, we tested MA6 for O157:H7 traits by PCR, starting with the rfbE gene that is essential for O157 antigen expression (1). Primers PF-38 (5′-CTGTTATGTTGTACTGCTTCA-3′) and PF-36 (5′-CAATTCCACCGCCCCACTCG-3′) were modified from the primers of Bilge et al. (1), and they amplify a 1,280-bp DNA sequence that includes the entire rfbE gene. Both TT12 and MA6 produced identical amplicons of the expected size for the rfbE fragment (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 5); hence, despite the absence of reactivity to most O157 sera, MA6 appears to carry genetic sequences essential for O157 antigen expression.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA fragments amplified from strains TT12 (O157:H7) and MA6 by PCR, using primers specific for various genes (shown in parentheses). Lanes: 1, 123-bp molecular size ladder; 2, TT12 (stx2, stx1, and uidA); 3, MA6 (stx2, stx1, and uidA); 4, TT12 (rfbE); 5, MA6 (rfbE); 6, TT12 (eaeA and EHEC plasmid); 7, MA6 (eaeA and EHEC plasmid).

Radu et al. (13) tested strain MA6 with DNA probe, PCR, and agarose gel electrophoresis to show the presence of eaeA, stx2, and the EHEC plasmid, respectively. Those results were verified in our study by PCR, using primers for these virulence factors (2, 10), as identical amplicons were obtained from both TT12 and MA6 for eaeA (397 bp), EHEC plasmid (166 bp), and stx2 (584 bp) (Fig. 1). Serological test for toxins (Verotox-F; Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) confirmed that MA6 produced only Stx2. Our PCR studies also showed that MA6 had the 252-bp amplicon from uidA (2), which specifically detects a T-to-G base change at +92 in the uidA allele (8). This base mutation is unique to the O157:H7 serotype (4) and is highly conserved in the O157:H7 clonal complex (9); therefore, the presence of this uidA base mutation in MA6 strongly suggests that it is of the O157:H7 serotype. This assumption was confirmed by testing for genetic relatedness by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (17), which showed that MA6 had the ET1 electrophoretic profile that is characteristic of O157:H7 (data not shown); hence, it is in the O157:H7 clonal group (9).

LPS analysis.

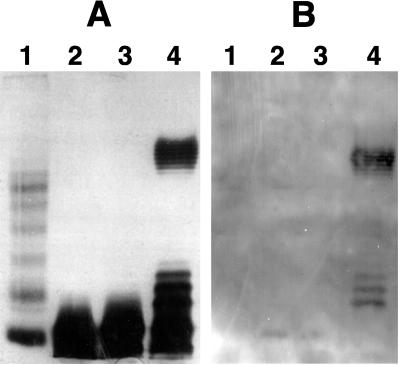

Strain MA6 is genetically like O157:H7 and carries the rfbE gene required for O157 antigen expression, yet it did not react with most anti-O157 sera. Hence, we examined the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of MA6 for the presence of the O side chain. The LPSs of MA6, TT12, and DH5α λpir (negative control) were isolated, fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and silver stained as described previously (14). All three isolates had low-molecular-weight LPS of the core region, but the high-molecular-weight ladder, characteristic of the O-polysaccharide side chain of smooth LPS (3), was present only in TT12 (Fig. 2A). DH5α λpir is a rough mutant of Escherichia coli, which has a LPS that is truncated at the core and therefore does not make the O side chain (11). The LPS profile of MA6 also lacks the O side chain and closely resembled that of DH5α λpir; hence, it appears that MA6 is also a rough strain. Rough mutants of E. coli (O-rough:K1:H7) that produce Stx1 have been isolated from patients with traveler’s diarrhea, but those strains were distinct phenotypically from O157:H7 and did not carry other EHEC virulence factors (16).

FIG. 2.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (A) and Western blot (B) of bacterial LPS. Lanes: 1, prestained Kaleidoscope molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.); 2, DH5α λpir; 3, MA6; 4, TT12. Blot was probed with anti-O157 serum from the Escherichia coli Reference Center, Pennsylvania State University.

To confirm the absence of the O157 antigen, a companion gel was Western blotted onto a polyvinylidine fluoride membrane (Schleicher & Schuell Inc., Keene, N.H.) (14) and probed with a 1:500 dilution of anti-O157 rabbit serum (Escherichia coli Reference Center, Pennsylvania State University). Antigen-antibody binding was detected by using a 1:1,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) and a precipitable substrate as reported previously (7). The results show that the high-molecular-weight O side chain of TT12 (O157:H7) reacted with the anti-O157 serum but so did some components in the core (Fig. 2B), which suggests that the anti-O157 serum had traces of antibodies to the LPS core. Neither DH5α λpir nor MA6 showed an antibody-reactive O side chain, but minor components in the core also reacted weakly with the serum. Since this anti-O157 serum was used by the reference center for serotyping, it is probable that the agglutination they observed with MA6 was due to these traces of antibodies to core LPS in the serum. A duplicate blot was probed with a cocktail of 4 of the 14 antisera (O124, O158, O57, and O87) from the reference center that had agglutinated with MA6. These antibodies also reacted weakly with the core LPS of MA6 and DH5α λpir (data not shown), which confirms that their reactivity with MA6 is also due to antibodies to the core LPS.

The absence of an O side chain in strain MA6 would account for the lack of its serological reactivity with most anti-O157 kits, but the positive reaction seen with some of the kits cannot be explained. Perhaps those kits that are positive with MA6 contain antibodies directed to other O157:H7-specific epitopes in addition to anti-O157 or, like the serum we used, contained traces of antibodies to the LPS core. Another possibility, at least with latex agglutination assays, may be the use of a heavy inoculum. False-positive latex agglutination reactions can occur if a sweep of growth is used for analysis instead of a single colony as recommended by the manufacturer (15). Regardless, this study shows the importance of evaluating commercial kits before using them routinely for screening for O157:H7 strains, as the specificity of some sera may not have been fully characterized.

In conclusion, we have identified a rough strain of E. coli O157:H7 that does not produce O side chain. MA6 has O157:H7-like phenotypes and virulence factors as well as the rfbE gene for O157 expression and is genetically O157:H7, but the absence of the O157 antigen would make this strain undetectable or unidentifiable with most serological assays used in the analysis of clinical or food samples for E. coli O157:H7.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Fratamico for providing eaeA and EHEC plasmid PCR primers, M. Davis and E. Sowers for serotyping, S. Cianci for graphics, and T. Whittam for clonal analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bilge S S, Vary J C, Jr, Dowell S F, Tarr P I. Role of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 O side chain in adherence and analysis of an rfb locus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4795–4801. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4795-4801.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cebula T A, Payne W L, Feng P. Simultaneous identification of strains of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and their Shiga-like toxin type by mismatch amplification mutation assay-multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:248–250. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.248-250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodds K L, Perry M B, McDonald I J. Electrophoretic and immunochemical study of the lipopolysaccharides produced by chemostat-grown Escherichia coli O157. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:2679–2687. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-9-2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng P. Identification of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 by DNA probe specific for an allele of uidA gene. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:151–154. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng P. Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7: novel vehicles of infection and emergence of phenotypic variants. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:47–52. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.950202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng P. Impact of molecular biology on the detection of foodborne pathogens. Mol Biotechnol. 1997;7:267–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02740817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng P, Fields P I, Swaminathan B, Whittam T S. Characterization of nonmotile variants of Escherichia coli O157 and other serotypes by using an antiflagellin monoclonal antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2856–2859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2856-2859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng P, Lampel K A. Genetic analysis of uidA expression in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. Microbiology. 1994;140:2101–2107. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng P, Lampel K A, Karch H, Whittam T S. Phenotypic and genotypic changes in the emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1750–1753. doi: 10.1086/517438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fratamico P M, Sackitey S K, Weidmann M, Deng M Y. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2188–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2188-2191.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahan M J, Slauch J M, Mekalanos J J. Selection of bacterial virulence genes that are specifically induced in host tissue. Science. 1993;259:686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.8430319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park C H, Hixon D L, Morrison W L, Cook C B. Rapid diagnosis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 directly from fecal specimens using immunofluorescence stain. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:91–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radu S, Mutalib S A, Rusul G, Ahmad Z, Morigaki T, Asai N, Kim Y B, Okuda J, Nishibuchi M. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the beef marketed in Malaysia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1153–1156. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1153-1156.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandlin R C, Lampel K A, Keasler S P, Goldberg M B, Stolzer A L, Maurelli A T. Avirulence of rough mutant of Shigella flexneri: requirement of O antigen for correct unipolar localization of IcsA in the bacterial outer membrane. Infect Immun. 1995;63:229–237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.229-237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sowers E G, Wells J G, Strockbine N A. Evaluation of commercial latex reagents for identification of O157 and H7 antigens of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1286–1289. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1286-1289.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vila J, Vargas M, Ruiz J, Gallardo F, Jimenez de Anta M T, Gascon J. Isolation of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O-rough:K1-H7 from two patients with traveler’s diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2279–2282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2279-2282.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittam T S, Wolfe M L, Wachsmuth I K, Orskov F, Orskov I, Wilson R A. Clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis and infantile diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1619–1629. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1619-1629.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]