Abstract

Objective:

Involving family members in a patient’s treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD) leads to more positive outcomes, but evidence-based family-involved treatments have not been adopted widely in AUD treatment programs. Study aims: (1) modify an empirically-supported 12-session AUD treatment, Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy (ABCT) to make it shorter and appropriate for any concerned family member, (2) conduct a small clinical trial to obtain feasibility data and effect-size estimates of treatment efficacy.

Method:

ABCT content was adapted to 3-sessions following input from clinicians, patients, and family members. Patient and family member dyads were recruited from an inpatient treatment program and randomized to the new treatment, Brief Family-Involved Treatment (B-FIT), or treatment-as-usual (TAU). Drinking was assessed using the Form-90; family support and family functioning were assessed using the Family Environment Scale Conflict and Cohesion subscales and the FACES-IV Communication scale. Dyads (n = 35) were assessed at baseline and 4-month follow-up.

Results:

On average, dyads received one of three B-FIT sessions with 6 dyads receiving no sessions due to scheduling conflicts or patient discharge. At follow-up, there was a large to medium effect size estimate favoring B-FIT for proportion drinking days (patient report, n = 22; Hedges’ g = 1.01; patient or family report, n = 28; Hedges’ g = .48). Results for family support or family functioning measures favored TAU.

Conclusions:

Implementation of brief family-involved treatment in inpatient AUD treatment was challenging, but preliminary data suggest the potential value of B-FIT in impacting drinking outcomes.

Keywords: family, alcohol use disorder, treatment, brief intervention

In 2020 there were an estimated 40.3 million Americans ages 12 and older with a substance use disorder (SUD), and of those individuals, 21.9 million had an alcohol use disorder (AUD) while 11.9 million had an illicit drug use disorder (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2022). Of those individuals with an SUD in 2020, only 21 percent received any treatment for it. Clearly, methods to improve engagement in treatment and treatment outcomes are sorely needed.

The central role that the family and others concerned about the individual with an AUD play in treatment engagement and outcomes is well documented. Evidence-based substance use treatments that involve a concerned significant other (CSO) have been shown to not only improve substance use treatment outcomes, but to also improve psychological and physical health outcomes for the CSO (Ariss & Fairbairn, 2020; Hogue et al., 2021). There are three broad types of evidence-based treatment approaches that involve CSOs. One approach is directed at family members to aid in their coping and to mitigate their own stress (Copello et al., 2009). A second approach involves interventions directed at family members that teach them communication skills and strategies to facilitate engagement in treatment for their treatment-resistant loved ones (Meyers et al., 1998; Thomas & Santa, 2007). The third approach is joint interventions to actively engage a CSO in treatment of the individual with the AUD or SUD (e.g., McCrady & Epstein, 2009a; 2009b; O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006). Despite significant evidence that family involvement leads to more positive treatment outcomes than individual treatment (McCrady et al. 2009c; O’Farrell et al., 2016; Powers et al., 2008), and the desire of family members to help their loved ones (McCrady et al., 2019), family-involved interventions remain significantly underutilized.

Several studies and reviews have delineated reasons for the poor utilization of evidence-based family-involved treatments. One reason is that researchers have typically focused on conducting efficacy trials that test treatments under controlled conditions with select populations but have not conducted studies focused on the dissemination of these treatments (McCrady et al., 2019). Relatedly, clinicians may disagree with the models underlying evidence-based approaches, and believe that findings from controlled trials have limited applicability to their ongoing clinical work (Houck et al., 2016, Schonbrun et al., 2012). In addition, there are reasons specific to the interventions themselves. One barrier to the widespread utilization of family-involved treatment is that these evidence-based interventions are lengthy and complex for clinicians to learn and deliver (Haug et al., 2008; McCrady et al., 2011; Schonbrun et al., 2012). Many clinicians lack appropriate training in couples or family-involved interventions and perceive them as too complex for routine use (e.g., Haug et al., 2008; McCrady et al., 2012; Schonbrun et al., 2012). There is also evidence that patients may be reluctant to have their families involved in their treatment or that family members may have concerns about feeling blamed for the patient’s substance use problems or responsible for the patient’s treatment (McCrady et al., 2011). In addition, there are pragmatic concerns such as scheduling and potential institutional barriers such as difficulties with third-party reimbursement for family treatment sessions (McCrady et al., 2019; Schonbrun et al., 2012).

In an attempt to improve efforts to disseminate empirically-supported family treatments for alcohol use, this research group adapted McCrady and Epstein’s (2009a) empirically-supported Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy (ABCT) to focus on the core active ingredients of the treatment and develop a brief-family involved model that could easily be integrated into ongoing alcohol treatment. The present study is the result of a treatment development grant (R34 AA023304) designed to develop the brief family-involved treatment and supporting research materials, and to conduct a preliminary test of the potential effectiveness of the treatment. Here we report the results of a randomized-controlled trial of this model, Brief Family-Involved Treatment (B-FIT), a three-session treatment whose focus is to (a) enhance family support for change efforts in the patient, (b) teach strategies to enhance positive reciprocity between the patient and family member, and (c) teach constructive communication skills to the patient and family member.

The aims of this study were to: (a) modify an empirically-supported couple treatment for AUD to make it brief, appropriate for any concerned family member, and appropriate for use as part of an ongoing alcohol treatment program, and (b) conduct a small-scale clinical trial to obtain preliminary feasibility data and effect-size estimates of efficacy of the adapted treatment, B-FIT, on drinking and family functioning outcomes.

Method

Design

This was a Stage 1a/Stage 1b treatment development design (Rounsaville et al., 2001). In Stage 1a, a draft B-FIT treatment manual was created, and focus groups were used to solicit feedback on the manual and family-involved treatment more generally. The manual was revised based on the feedback, and used in a Stage 1b randomized trial to compare the efficacy of B-FIT to treatment as usual (TAU). The study was reviewed and approved by the University of New Mexico Institutional Review Board and approved by the State of New Mexico Department of Health board per the New Mexico “Review of Proposed Research on and Protection of Human Subjects” policy (Policy # ADM 02:132). The study is registered on Clinical Trials.gov (protocol NCT05545644) but was not pre-registered.

Setting

The study was conducted in a publically funded 40-bed inpatient SUD treatment program that served all of northern New Mexico and offered medical detoxification (5–7 days), residential social model rehabilitation (18–21 days), and was in the process of starting an intensive outpatient service while the study was on-going. The residential program (treatment as usual [TAU] for the study) included several hours per day of therapy groups, some individual counseling, on-site AA meetings, and recreational activities, but no family involvement in treatment. The facility had more than 1000 admissions per year, with most patients receiving detoxification only.

Participants

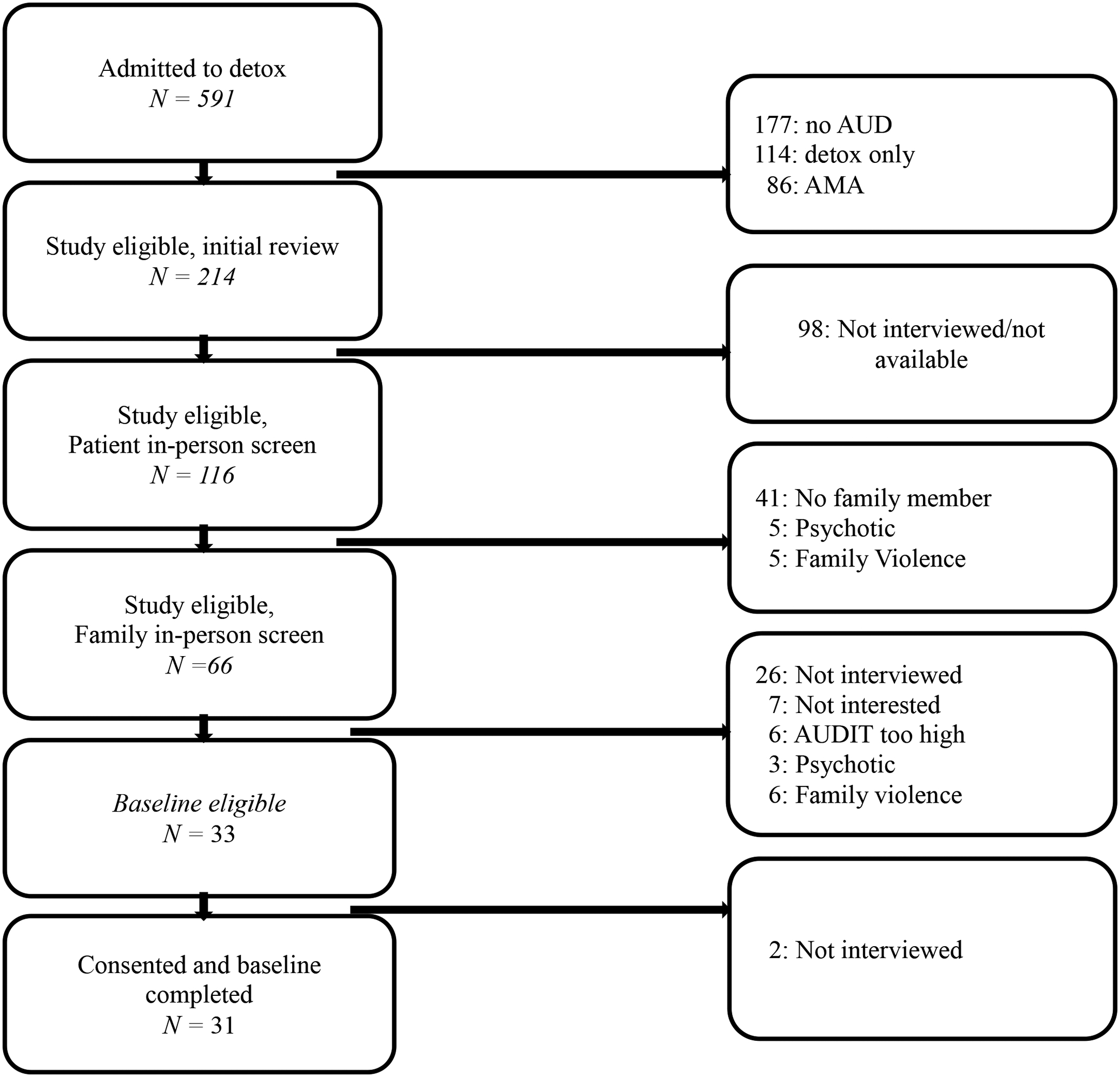

Thirty-five dyads (Identified Patients [IPs] and their CSO) consented to study participation and were randomly assigned to B-FIT (n = 18) or TAU (n = 17). Figure 1 shows the flow of potential study participants. IP inclusion criteria were: (a) having a family member the IP rated as important, very important or extremely important; (b) score of ≥ 8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993); (c) negative responses to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 2002) psychotic screener (no to all questions or if any positive symptoms occurred only in the context of substance use); and (d) negative responses to a two-question domestic violence screener (Feldhaus et al., 1997). CSO inclusion criteria were: (a) willing to participate in the study; (b) AUDIT ≤ 8; (c) negative responses to the SCID for DSM-IV psychotic screener; and (d) negative on a domestic violence screener. Although not an exclusion criterion, no CSO had evidence of another SUD based on responses to the DAST (range = 0–3; 25 reported a 0).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. Note that complete data before research staff attempted to conduct baseline interviews are not available.

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of the sample. Contingent on the scale of measurement, t-tests and Chi square tests within dyad role indicated that IPs assigned to B-FIT and TAU did not differ significantly on any of the demographic variables in Table 1. However, there was a large effect size favoring TAU for CSO race; and a medium effect size for CSO employment favoring TAU. A majority of the IPs reporting they were white males in their early forties, single, had a high school diploma and were currently unemployed. Further examination of effect sizes with Hedges g or ETA suggested no additional notable differences between groups. The nature of the CSO-IP relationship was relatively balanced across the two groups. In B-FIT, CSOs consisted of six mothers, two fathers, two wives, three sisters, two brothers, two girlfriends, and one grandmother. In TAU, the CSOs included six mothers, two fathers, two wives, two sisters, one brother, two girlfriends, and two boyfriends. In general, CSOs were socially more stable than IPs and, with the exception of racial/ethnic status, where B-FIT CSOs were less likely than TAU CSOs to be white, were similar across the two treatment conditions. Specifically, a majority of the CSOs were female, lived with a spouse, and were in their mid-to-late fifties. On average, CSOs reported 2–3 years of post-secondary education.

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics

| IP | CSO | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-FIT (n = 18) | TAU (n = 17) | p | ETA/g1 | B-FIT (n = 18) | TAU (n = 17) | p | ETA/g1 | |

| Male | 14 (77.8%) | 13 (76.4%) | .99 | .02 | 4 (22.2%) | 5 (29.4%) | .92 | .08 |

| Age | 42.06 (10.14) | 44.65 (9.49) | .44 | .26 | 55.89 (14.10) | 59.47 (12.16) | .43 | .27 |

| White | 12 (66.7%) | 11 (64.7%) | .67 | .18 | 7 (38.9%) | 11 (64.7%) | .01 | .56 |

| Living w/spouse | 4 (22.2%) | 7 (41.1%) | .46 | .32 | 12 (66.7%) | 14 (82.4%) | .38 | .26 |

| Married | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.9%) | .69 | .26 | 9 (50.0%) | 6 (35.3%) | .72 | .22 |

| Employed | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.9%) | .72 | .24 | 6 (33.3%) | 11 (64.7%) | .09 | .44 |

| Mean annual income | $27,317 | $31,366 | .59 | .18 | $52,485 | $58,158 | .32 | .33 |

| Years education | 13.39 (194) | 12.71 (2.57) | .38 | .29 | 15.11 (3.27) | 14.11 (2.39) | .43 | .34 |

ETA is reported for categorical variables; Hedges g for continuous variables

Table 2 displays IP alcohol use and help-seeking at baseline. t-tests with bootstrapping and additional examination of 95% confidence intervals indicated that IPs assigned to B-FIT and TAU did not differ on any of the alcohol use measures or help-seeking activities prior to recruitment, although effect size estimates showed a medium effect size favoring B-FIT participants on PDA and AA attendance prior to treatment. In general, consented IPs were in the moderate-to-severe range for AUD (average AUDIT score > 15). IPs reported drinking about 14–17 standard drinks of alcohol per drinking occasion and had consumed alcohol about 65–80% of the available days in the 90-day retrospective baseline assessment. Regarding help-seeking, IPs reported some initial efforts to seek help through formal treatment and community-based AA, but such efforts were quite limited; only 8 of 35 (23%) reported any formal treatment days before recruitment and about 29% (10 of 35) reported having attended AA prior to study recruitment. Twenty-one (60%) IPs reported no help seeking at all in the 90-day period before recruitment.

Table 2.

IP Baseline Alcohol Use, Help-Seeking and Family Functioning by Group Assignment: Means (SD)

| B-FIT (n = 18) | 95% CI1 | TAU (n = 17) | p | g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDIT | 33.88 (5.12) | (−3.43 – 4.14) | 33.53 (5.69) | .85 | .06 |

| DAST | 3.76 (3.61) | (−2.04 – 2.99) | 3.29 (3.58) | .71 | .13 |

| Proportion Alcohol Abstinent Days | .35 (.33) | (−.06 - .38) | .19 (.31) | .16 | .49 |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 17.05 (6.43) | (−2.14 – 7.06) | 14.59 (6.94) | .28 | .36 |

| Proportion Heavy Drinking Days | .65 (.33) | (−.44 - −.05) | .79 (.34) | .22 | .43 |

| Proportion Alc. Treatment Days2 | .04 (.14) | (−.04 - .10) | .01 (.04) | .42 | .28 |

| Proportion AA Days | .10 (.18) | (−.04 - .17) | .03 (.12) | .24 | .64 |

| Commitment to Sobriety | 26.22 (8.00) | (−6.02 – 3.76) | 27.35 (6.01) | .64 | .16 |

| FES Conflict | 5.56 (1.25) | (−.82 – 1.58) | 5.18 (2.16) | .53 | .21 |

| FES Cohesion | 3.61 (1.29) | (−.40 – 1.27) | 3.18 (1.13) | .30 | .35 |

| Family Communication Scale | 34.89 (9.81) | (−6.35 – 5.66) | 35.24 (7.40) | .91 | .04 |

95% confidence intervals for the difference in the means being contrasted

Proportion Alc Treatment Days equals the number of days of residential and/or outpatient alcohol treatment days in the prior 90 days to baseline divided by 90. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test, AA = Alcoholics Anonymous, FES = Family Environment Scale.

Summary measures of CSO baseline functioning and impressions of family functioning are presented in Table 3. As shown, t-tests with bootstrapping and additional examination of 95% confidence intervals indicated the absence of mean differences on any of the seven CSO measures. On average, CSOs reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, et al., 1988) scores in the minimal distress range (0–13 indicates minimal depressive symptomatology); likewise, mean Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI, Beck, Epstein, et al.,, 1988) scores fell within the minimal range (0–7 indicates mild anxiety). Mean standardized scores on the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 2009) Conflict scale were at about the 61st percentile and were at about the 28th percentile on the Cohesion scale. Finally, CSO reported alcohol (AUDIT) and illicit drug use (DAST) indicated non-problematic or nonhazardous use of substances.

Table 3.

CSO Baseline Functioning at Baseline by Group Assignment: Means (SD)

| B-FIT | 95% CI1 | TAU | p | g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDIT2 | 1.53 (1.87) | (−1.83 – 1.00) | 1.94 (2.16) | .56 | .20 |

| DAST | .31 (.79) | (−.40 – .53) | .25 (.45) | .79 | .09 |

| BDI | 7.00 (5.11) | (−3.22 – 6.63) | 5.29 (8.83) | .49 | .23 |

| BAI | 3.47 (3.87) | (−5.12 – 3.12) | 4.47 (7.37) | .62 | .02 |

| FES-Conflict | 5.28 (1.27) | (−1.12 - .73) | 5.47 (1.55) | .68 | .13 |

| FES-Cohesion | 3.56 (.92) | (−.59 - .64) | 3.53 (.87) | .93 | .03 |

| Family Communication Scale | 35.56 (8.09) | (−4.29 – 7.76) | 33.82 (9.42) | .56 | .02 |

95% confidence intervals for the difference in the means being contrasted

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, FES = Family Environment Scale.

Measures

Screening:

IPs and CSOs were screened for study eligibility by program clinical staff using the AUDIT (Saunders et al., 1993) to assess for alcohol problems, the SCID for DSM-IV Psychotic Screener (First et al., 2002) to screen out individuals who were actively psychotic, and a two-question screener for intimate partner violence (IPV, Feldhaus et al., 1997) to assess past year harm from IPV or fear of IPV if they participated in joint treatment sessions.

IP baseline:

Demographic and locator information were assessed using standardized measures developed at the Center on Alcohol, Substance Use, and Addictions (CASAA) that assessed New Mexico-relevant and general IP characteristics. Drinking (past 3 months) was assessed using the Form-90 (Miller et al., 1995; Tonigan et al., 1997) and alcohol use consequences (lifetime) were assessed with the Drinking Inventory of Consequences (DrINC, Miller et al., 1995). Proportion abstinent days (PrDA), derived from the Form-90, was the primary outcome variable. Proportion days heavy drinking (PrDH) and drinks per drinking day (DPDD) were secondary drinking outcome variables. The Commitment to Sobriety Scale (Kelly & Greene, 2014) assessed IP motivation to change. Family relationships were assessed with the Perceived Social Support – Family scale (PSS-Fa; Procidano & Heller, 1983), the Conflict and Cohesion scales from the FES (Moos & Moos, 2009), and the FACES-IV Family Communication Scale (Olson, 2011).

CSO baseline:

Demographic data were assessed using the same CASAA measure. CSO depression and anxiety were assessed using the BDI (Beck, Steer, et al., 1988) and BAI (Beck, Epstein, et al., 1988). CSOs also completed the Conflict and Cohesion scales from the FES (Moos & Moos, 2009), and the FACES-IV Family Communication Scale (Olson, 2011).

Follow-up:

IP:

At the 4-month follow-up IPs were interviewed using the Form-90, follow-up version, and completed follow-up versions of the DrINC, Commitment to Sobriety Scale, PSS– Family, Conflict and Cohesion scales of the FES, and the FACES-IV Family Communication Scale.

CSO:

At the 4-month follow-up CSOs completed the BDI, BAI, Conflict and Cohesion scales of the FES, and FACES-IV Family Communication Scale. Part-way through the study we obtained IRB permission to add the family follow-up version of the Form-90 interview to obtain CSO reports of IP drinking.

Procedures

Development of treatment materials.

Based on initial clinician feedback, our aim was to develop a 3-session treatment manual that could be used flexibly in an SUD treatment program. Based on the literature and prior work, the authors (BSM, BF, BE) identified three major elements of family-involved treatment – family support for change, positive reciprocity, and enhanced communication skills. These elements were extracted from the ABCT therapist guide and client workbook (McCrady & Epstein, 2009a, 2009b) and from the work of O’Farrell and Fals-Stewart (2006) and modified to be applicable to any family member rather than just intimate partners. We then conducted focus groups with 15 clinicians, patients, and family members (see McCrady et al., 2019 for details) to solicit input on the content of the treatment manual, identified specific suggestions and major themes through qualitative analyses, and modified the treatment manual based on this feedback to include more psychoeducation about AUDs, information relevant to the impact of AUD on children, and more shared activities geared to lower-income households. We then developed a parallel workbook of handouts and worksheets for IPs and CSOs.

Final treatment manual.

Session 1 provided a rationale for CSO involvement, psychoeducation about the etiology of AUD and other SUDs and the process of change, a rationale for increasing positive relationship interactions, and helped the IP and CSO identify specific ways to be supportive to each other. Session 2 included a review of supportive behaviors and shared positive activities from Session 1, introduced effective communication skills, had the dyad practice one communication skill during the session, and then helped the dyad develop a recovery contract (e.g., O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006). Session 3 reviewed the use of skills from Sessions 1 and 2, continued communication skills training, and concluded with a discussion of how to continue to use the skills introduced in the three treatment sessions.

Clinician training and supervision.

Five clinicians (four master’s level licensed alcohol and drug abuse counselors; one doctoral level psychologist) at the treatment program were trained on the B-FIT treatment manual in one two-hour training session. Two of the authors (BSM, BF) met with the clinicians each week to review cases and issues related to the implementation of the B-FIT study protocol. Sample audiotapes of B-FIT sessions were reviewed by the authors.

Procedures for data collection.

All research data were collected by trained interviewers.

Screening.

At daily morning rounds clinical program staff reviewed information about newly admitted patients for potential study eligibility. Clinical program staff documented the results of screening of all admissions to the facility from 1/1/2018 through 9/8/2018 (Figure 2), but did not continue detailed tracking after that date even though the study continued. During the time that clinical program staff tracked all facility admissions, patients ineligible for the study included approximately 30% of admitted patients had no AUD, 20% had been admitted for detoxification only, and 14.5% left against medical advice (McCrady et al., 2019). After patients completed a full biopsychosocial intake assessment (within 72 hours of admission) clinical program staff approached them to discuss potential study involvement and conduct the initial screening. They were able to approach approximately 55% of these patients – others were not available or program staff did not have time to conduct the initial screening.

Figure 2.

Patient flow at the treatment facility, 1/1/2018 – 9/8/2018. Program staff discontinued tracking after 9/8/2018 but continued to recruit study participants.

Recruitment.

Eligible patients signed medical releases of information for clinical program staff to contact their CSO and the B-FIT research staff. Clinical program staff then contacted and screened the CSO. If the CSO also was eligible and willing to participate, the B-FIT research team was notified and baseline interviews were scheduled.

Informed consent, baseline collection, and randomization.

Baseline interviews and self-report data were collected by B-FIT research staff in separate appointments with the IP and CSO. At the end of the CSO baseline, dyads were randomized to the B-FIT intervention or TAU, using urn randomization to counter-balance the conditions on sex, severity of AUD (based on AUDIT score), and type of CSO (partner, parent, other). IPs were compensated $50 for completing the baseline; CSOs were compensated $30.

Follow-up and tracking procedures.

IPs and CSOs were followed up four months after their baseline interview. Multiple attempts (median = 11; range 1–41 attempts) were made to reach each participant through calls, texts, emails, letters, and contact with locators if IPs were lost to follow-up. IPs and CSOs were each compensated $40 for completing the research follow-up.

Clinician feedback.

At the conclusion of the clinical trial, the five program clinicians met with the clinical supervisors (BSM, BF) to obtain unstructured feedback and suggestions for B-FIT. This feedback was summarized in narrative fashion around four topics: general feedback, barriers to implementation, suggested changes to the B-FIT treatment manual and workbook, and implementation of B-FIT in a clinical rather than research setting.

Data Analysis Plan

For descriptive purposes, where appropriate, we have computed 95% confidence intervals of the difference of the mean, and Hedges g effect sizes adjusted for small sample bias. For categorical measures, ETAs are reported.

Lost to follow-up analyses.

2 × 2 Chi Squares (grouped by follow-up status, interviewed versus lost) tested for differential attrition by group for IPs and CSOs. Two logistic regressions with follow-up status as the criterion (interviewed versus lost) were then conducted to assess if baseline severity of IPs or CSOs (irrespective of group assignment) predicted study attrition. Additional logistic regressions were run with CSO follow-up status as the criterion (interviewed versus lost) with CSO baseline BDI and BAI scores and IP drinking severity as predictors.

Patient/family member agreement.

This set of analyses had two objectives: (1) to assess the concordance between IP and CSO reports of IP alcohol use, and (2) to assess whether CSO report of IP drinking could be substituted for missing IP drinking data at 4 months. To this end, bivariate correlations were computed between IP and CSO reports on drinking variables. Twenty-two of the CSOs provided sufficient data to compute IP proportion abstinent days at the four month interview, and 16 of these CSOs could be paired with IP report of drinking provided at 4 months.

Main outcomes analyses.

To assess outcomes, IP measures of self-reported drinking and consequences as well as family functioning and CSO measures of self-reported depression and anxiety along with reports of family functioning and IP drinking were examined using planned and unprotected general linear models (GLMs) with baseline values of the 4-month dependent variable entered as covariates. Hedges’ g effect sizes that adjust for small sample size were computed to provide a measure of magnitude of effect. To aid interpretation of Hedges g, we report the standard error of the obtained effect size.

De-identified study data are available upon request to the first author.

Results

Control Analyses

Examination of differential attrition.

Twenty-two (62.9%) of the IPs were interviewed at the 4 month follow-up (7 lost in B-FIT and 6 lost in TAU) while 27 (77.1%) of the CSOs were contacted and interviewed at 4 months (3 lost in B-FIT and 5 lost in TAU). Chi Squares (grouped by follow-up status, interviewed versus lost at 4 months) indicated that there was no significant differential attrition by group for either the IPs (x2 (1) = .05, p < .83) or CSOs (x2 (1) = .81, p < .37). To further examine possible differential attrition we calculated ETAs, which were .02 for IP attrition and .15 for CSO attrition, further supporting that there were not differences between groups in attrition from follow-up. Logistic regressions with follow-up status as the criterion (interviewed versus lost) were then conducted to assess whether baseline severity of IPs or CSOs (irrespective of group assignment) predicted study attrition. For the IPs (n = 22), baseline severity was defined with three predictors – proportion alcohol abstinent days, drinks per drinking day, and proportion heavy drinking days - and for CSOs the baseline predictors were scores on the BDI and BAI. Neither logistic regression was significant, suggesting that baseline IP alcohol severity and CSO functioning severity were unrelated to study attrition at 4 month follow-up: IP: χ2(3) = .13, p < .99; CSO: χ2 (2) = 1.31, p < .52. Finally, we examined the association between frequency of B-FIT session attendance and 4 month follow-up status, to determine if not attending B-FIT sessions extended to predicting non-compliance with the 4-month interview. There was no evidence that not attending B-FIT sessions predicted non-compliance with the research protocol; 4 of the 6 IPs with no B-FIT sessions were interviewed at 4 months and, 5 of the 6 CSOs reporting no B-FIT sessions were interviewed at 4 months.

Relationship between IP and CSO reports of follow-up drinking.

Twenty-two CSOs provided sufficient data to compute IP proportion abstinent days at the 4-month interview, and 16 of these CSOs could be paired with IP report of drinking provided at 4 months. The correlation was positive and significant, r = .62, p < .01. Noteworthy, this correlation increased to r = .74, p < .002, with the removal of one paired IP-CSO case that had grossly discrepant reports of IP drinking. We concluded that we could be relatively confident of IP self-reported drinking and that CSO report of IP drinking could be substituted for missing IP 4-month drinking data (6 paired cases where this could be applied).

Treatment Utilization

Among dyads randomized to B-FIT, 6 received no B-FIT treatment sessions, 8 received one session, 1 received two sessions, and 3 completed all three sessions, for a mean of 1.05 sessions attended.

Outcomes

Table 4 shows the results of the planned and unprotected GLMs with baseline values of the 4-month dependent variable entered as covariates for all outcome variables.

Table 4.

Four-Month Study Drinking and Family Functioning Outcomes: Means (SE) and Effect Sizes1 (g)

| IP Outcomes | B-FIT (n = 11)2 | TAU (n = 11)2 | Wald | Hedges g | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion Abstinent Days | .85 (.05) | .65 (.11) | 2.47, p = .12 | 1.01 | .55 |

| Proportion Abstinent Days with CSO reports added2 | .78 (.06) | .64 (.10) | 1.50, p = .22 | .48 | .48 |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 12.04 (3.65) | 6.56 (2.49) | 1.46, p = .23 | .60 | .48 |

| Proportion Heavy Drk Days | .13 (.05) | .36 (.12) | 2.98, p = .08 | 1.22 | .54 |

| DrInC Total Consequences | 18.82 (4.76) | 12.71 (4.52) | .89, p = .37 | .37 | .45 |

| CSS3 | 25.10 (1.51) | 24.90 (1.44) | .01, p = .92 | .01 | .41 |

| FES-Conflict | 5.45 (.47) | 5.64 (.35) | .10, p = .76 | .04 | .42 |

| FES-Cohesion | 2.91 (.37) | 3.45 (.37) | 1.07, p = .30 | .44 | .63 |

| Family Comm. Scale | 32.20 (3.44) | 38.18 (1.99) | 2.27, p = .13 | .93 | .52 |

| PSS-Family Scale | 26.08 (4.02) | 31.46 (5.06) | .66, p = .41 | .27 | .44 |

| CSO Outcomes | B-FIT (n = 14) | TAU (n = 12) | Wald | Hedges g | SE |

| Depression (BDI) | 7.21 (1.71) | 5.15 (1.24) | .88, p = .35 | .33 | .46 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | 5.79 (1.63) | 4.67 (1.91) | .20, p = .66 | .08 | .42 |

| FES-Conflict | 4.86 (.58) | 5.67 (.48) | 1.17, p = .28 | .44 | .47 |

| FES-Cohesion | 3.43 (.39) | 3.75 (.24) | .50, p = .48 | .19 | .44 |

| Family Comm. Scale | 33.86 (2.43) | 36.08 (2.88) | .35, p = .56 | .13 | .43 |

4-month means adjusted for baseline values of the measure.

N = 14 with CSO reports; B-FIT = 14; TAU = 14.

CSS = Commitment to Sobriety Scale; Family Comm. Scale = Family Communication Scale; FES = Family Environment Scale; PSS = Perceived Social Support

IP drinking outcomes.

Primary 4-month outcomes for IPs included measures of self-reported drinking and consequences as well as family functioning. Hedges’ g effect sizes that adjust for small sample size were computed to provide a measure of magnitude of effect. All unprotected between-group GLM tests were non-significant. Large effect sizes were observed for proportion abstinent days and proportion heavy drinking days, both of which favored the B-FIT group. The effect size for drinks per drinking day was in the medium range, with results favoring TAU. Together, the results suggested less frequent drinking, but heavier drinking on drinking days by B-FIT participants. CSOs provided follow-up data necessary to compute 4-month IP proportion abstinent days and 6 of these CSO reports were substituted for missing IP report to provide additional statistical power in a post hoc GLM test. The general pattern of findings remained the same, with 28 cases (22 IP and 6 CSO reports of IP drinking) in this post hoc analyses, Wald = 1.30, p < .25, g = .48, although the relative magnitude of B-FIT benefit was reduced. When taking the standard error into account in examining the magnitude of the effect size for PDA based on IP report we still observe at least a medium effect size favoring the B-FIT intervention. The findings with CSO data added follow a direction similar to the results of analyses using only IP data, but are substantially smaller in magnitude.

IP family functioning outcomes.

Unprotected between-group GLM tests of the three family variables were non-significant, but there was a medium to large effect size favoring TAU on the Family Communication Scale.

CSO outcomes.

Among the CSOs, outcomes included self-report of depression and anxiety as well as reports of family functioning. All unprotected between-group GLM tests were non-significant and no effect size estimates were in the medium-to-large range.

Program Clinician Feedback

General feedback.

Program clinicians noted the high level of conflict and resentment in families, and observed that patients often were reluctant to ask family members to participate in treatment. They noted that a family member typically brought the IP to the treatment facility and suggested that, in the future, program staff could approach family members then about participation. They also noted that dyads who participated in the program “loved it,” and saw the sessions as “opening up possibilities” for them.

Barriers to implementation.

Program clinicians noted that delays in reaching family members and in scheduling baseline assessments with both members of the dyad resulted in little time to deliver the B-FIT treatment sessions within the 3-week treatment program. They noted that it was difficult for dyads to implement homework in the inpatient setting. They also indicated that scheduling B-FIT sessions during the work week was difficult to coordinate clinicians and family member schedules. They suggested the potential value of telehealth rather than face-to-face sessions, and making evening and weekend sessions available as well.

Suggested changes to the B-FIT treatment manual.

Program clinicians were particularly positive about the recovery contracts and communication material. They suggested bullet-pointed rather than narrative instructions in the therapist manual to make it easier for them to follow the material. They also suggested including an introductory session that allowed for more general communication between the IP and CSO.

Implementation of B-FIT in a clinical setting.

Program clinicians suggested that B-FIT would be better suited to an ambulatory treatment setting where sessions could be scheduled more flexibly based on patient need rather than being fit into a short inpatient treatment program.

Discussion

The overall aim of this R34-supported research was to develop and test the efficacy of a brief, family-involved treatment for AUD appropriate for any concerned family member that could be integrated into an ongoing alcohol treatment program, that would be easy to implement, and that would enhance treatment outcomes. Results suggested that an inpatient setting is probably not optimal for the B-FIT intervention. The complexity of implementing a randomized clinical trial requiring multiple layers of consents and assessments before providing the intervention limited the ability to deliver the face-to-face intervention within the timeframe of the inpatient treatment program, resulting in six dyads receiving no B-FIT sessions at all, and an average of only one session received across dyads. In addition, scheduling conjoint sessions within the constraints of clinician schedules (who worked days) and CSO schedules (many of whom were not available during clinician day time working hours) created an additional barrier to implementation. Overall, results provide some limited evidence for the positive impact of this very brief intervention on drinking outcomes, with large effect sizes favoring B-FIT for frequency of drinking and heavy drinking among IPs. However, there was no comparable effect on family functioning outcomes, with measures of conflict, cohesion, and communication all showing moderate to large effects sizes favoring TAU over B-FIT.

The overall aims of the R34 were achieved in part. We were successful in developing the treatment, treatment materials, and clinician training materials. The treatment was easy to train and acceptable to clinicians and staff. Thus, the B-FIT protocol overcame many of the barriers of other family-involved treatments and was flexible in being applicable to a wide variety of family members. In addition, clinicians and family members who engaged with the treatment expressed enthusiasm for the intervention. The drinking outcome data from the clinical trial were promising, but impacts on family functioning were minimal or seemed to favor TAU. We are at a loss to explain the family functioning results, but it is possible that the B-FIT sessions highlighted conflicts in dyads without sufficient time to address these conflicts in the treatment. It also is possible that the willingness of family members to participate in the study led to a more positive view of the relationship in TAU, without raising new or conflictual issues that might have been raised in the B-FIT sessions. Better strategies for engaging family members and making the treatment more accessible should be incorporated into further tests of B-FIT.

Previous research on family engagement in inpatient settings has suggested that patients undergoing detoxification for opioid dependence (Schonbrun et al., 2016) and families of patients in AUD treatment (McCrady et al., 2019) express enthusiasm for family involvement. However, one previous pilot study to engage families of patients undergoing detoxification from alcohol (O’Farrell et al., 2008) faced similar challenges in engaging families in the intervention – among 897 patients admitted to the detoxification program during the study, less than 25% (201) lived with a family member. Of those, close to 25% lived too far away, 16% did not meet other study criteria, and close to 40% “were not randomized for a variety of other reasons (e.g., weekends or holidays when staff were unavailable, staff errors in identifying potential study patients)” (O’Farrell et al., p. 364), leaving 46 patients who were randomized (about 5% of the total patient population). Results also were similar to the present study with trends toward greater probability of continuing treatment beyond detoxification and less alcohol consumption.

Overall, the present study had notable strengths as well as limitations. The B-FIT intervention draws on principles and content from well-established, empirically supported, family-involved treatments and received a very positive response from front-line clinicians although we do not have ratings of treatment satisfaction from study participants. The study was conducted in a real-world clinical setting, and engaged an ethnically diverse population. One study limitation may be that, for ethical reasons, dyads with severe domestic violence were screened out. Thus, the sample was not fully representative of individuals with AUD who have a concerned family member, but we believe that any study involving family members in any type of conjoint therapy should screen out such dyads. Prior research with couple therapy for AUD has found that, despite screening out severe domestic violence, more than 60% of couples report some level of domestic violence (Drapkin et al., 2005). In addition, the small sample size and incomplete delivery of the B-FIT intervention made it difficult to detect possible positive or negative impacts of the treatment. It is also possible that there were iatrogenic study effects for TAU participants who did not receive the B-FIT intervention. It also is possible that the very limited exposure to B-FIT for dyads randomized to the family intervention to might have raised IP hopes for improved family communication, but not provided sufficient treatment to effect change.

Combined with the feedback from clinicians who implemented B-FIT, and the results of previous research (e.g., McCrady et al., 2019; O’Farrell et al., 2008; Schonbrun et al., 2016) the results of the present study suggest a strong interest among clinicians, family members, and patients in involving families in brief AUD or SUD treatment, but the “formula” to do so still needs refinement and development. Several future refinements might enhance the generalizability of these interventions. First, a more flexible model for delivery of the treatment, including availability of a telehealth-based format and flexible hours for scheduling appointments should make the treatment more accessible. The B-FIT study was implemented before the COVID-19 pandemic, and strong evidence for the value of telehealth for couples has been reported during the pandemic (Flanagan et al., 2021). A second way to enhance flexibility in implementation would be to test B-FIT in an ambulatory setting (e.g., intensive outpatient or standard outpatient treatment) that has less constraints on the time frame to provide the intervention. Third, programs could find more natural ways to “capture” family members – either when they are bringing a patient to treatment for the first time, or at other natural times they might be in contact with the treatment program (e.g., driving the patient to IOP visits). Finally, B-FIT clinicians provided valuable feedback on ways to modify the treatment manual content and formatting to make it even easier to implement and more responsive to what they perceived as IP and CSO needs. With these modifications, a full-scale effectiveness clinical trial would be warranted.

Public Health Significance:

Family-involved treatments for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) hold considerable promise to improve treatment engagement, compliance, and outcomes. However, these treatments are time-intensive and difficult to learn and to integrate with on-going clinical treatment. This paper reports the development and initial testing a brief, 3-session, family-involved treatment that can be incorporated into on-going AUD treatment. The promising findings suggest that the treatment may increase the efficiency and effectiveness of AUD treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant AA R34-023304 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors are grateful to the staff at the Turquoise Lodge Hospital for their support in the conduct of the research and to the families who participated in the study.

Footnotes

De-identified study data are available upon request to the first author.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05545644

References

- Ariss T, & Fairbairn CE (2020). The effect of significant other involvement in treatment for substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88, 526–540. 10.1037/ccp0000495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Garbin MG (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8(1), 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2022). Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Copello A, Templeton L, Oxford J, Velleman R, Patel A, Moore L MacLeod J, & Godfrey C (2009). The relative efficacy of two levels of primary care intervention for family members affected by the addiction problem of a close relative: A randomized trial. Addiction, 104, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demographics interview (n.d.). Albuquerque, NM: Center on Alcohol, Substance use, And Addictions (CASAA), University of New Mexico. http://casaa.unm.edu/inst.html [Google Scholar]

- Drapkin ML, McCrady BS, Swingle J, Epstein EE, & Cook SM (2005). Exploring bidirectional couple violence in a clinical sample of female alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, & Abbott JT (1997). Accuracy of 3 Brief Screening Questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA, 277(17), 1357–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (2002). Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P), New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JC, Hogan JN, Sellers, Melkonian AJ, Jarnecke AM, Brown DG, Brower JL, Kirby CM, Mummert K, Santa Ana EJ, Lozano BE, Bottonari K, & McCrady BS (2021, June). Preliminary feasibility and acceptability of Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy delivered via home-based telehealth. Poster presented for presentation at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism (virtual). [Google Scholar]

- Haug NA, Shopshire M, Tajima B, Gruber V, & Guydish J (2008). Adoption of evidence-based practices among substance abuse treatment providers. Journal of Drug Education, 38, 181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Schumm JA, MacClean A, & Bobek M (2021). Couple and family therapy for substance use disorders: Evidence base update 2010–2019. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48, 178–203. 10.1111/jmft.12546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck JM, Forcehimes AA, Davis MM, & Bogenschutz MP (2016). Qualitative and quantitative feedback following workshop training in evidence-based practices: A dissemination study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 47, 413–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, & Greene MC (2014). Beyond motivation: Initial validation of the Commitment to Sobriety Scale. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46, 257–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L, Barber JP, Siqueland L, Johnson S, Najavits LM, Frank A, & Daley D (1996). The Revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAa-II). Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 5, 260–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Miller WR, Hill DE, & Tonigan JS (1998). Community reinforcement and family training (CRAFT): Engaging unmotivated drug users in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse, 10, 291–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, & Epstein EE (2009a). Overcoming alcohol problems: A couples-focused program. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, & Epstein EE (2009b). Overcoming alcohol problems: Workbook for couples. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Jensen N, & Hildebrandt T (2009c). A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Tonigan JS, Fink BC, Chávez R, Martinez A, Fokas K, Wilson A, Epstein EE, & Rouge S (2019, June). Barriers to involving families in alcohol treatment in a publically funded facility. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Wilson A, Fink BC, Borders A, Munoz R, & Fokas K (2019). A consumer’s eye view of family-involved alcohol treatment. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 37, 43–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS & Longabaugh R (1995). The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 4. DHHS Publication No. 95–3911. Rockville MD: NIAAA. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R, & Moos B (2009). Family Environment Scale Manual and Sampler Set: Development, Applications and Research (Fourth Edition). Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ & Fals-Stewart W (2006) Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse. NY: Guilford Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy M, Alter J, & Fals-Stewart W (2008). Brief family treatment intervention to promote continuing care among alcohol-dependent patients in inpatient detoxification: A randomized pilot study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34, 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Schumm JA, Murphy MM, & Muchowski PM (2017). A randomized clinical trial of behavioral couples therapy versus individually-based treatment for drug-abusing women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(4), 309–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D (2011). FACES IV and the circumplex model: Validation study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 3, 64–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Vedel E, & Emmelkamp PMG (2008). Behavioral couples therapy (BCT) for alcohol and drug use disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 952–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, & Heller K (1983). Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8(2), 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Screening Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonbrun YC, Anderson BJ, Johnson JE, & Stein MD (2016). Feasibility of a supportive other intervention for opiate-dependent patients entering inpatient detoxification. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 48(3), 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonbrun YC, Stuart GL, Wetle T, Glynn TR, Titelius EN, & Strong D (2012). Mental health experts’ perspectives on barriers to dissemination of couples treatment for alcohol use disorders. Psychological Services, 9(1), 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982). The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors, 7, 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, & Santa CA (1982). Unilateral family therapy for alcohol abuse: A working conception. American Journal of Family Therapy, 10, 49–58. DOI: 10.1080/01926188208250088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, Santa CA, Bronson D & Oyserman D (1987) Unilateral family therapy with the spouses of alcoholics, Journal of Social Service Research, 10, 145–162, DOI: 10.1300/J079v10n02_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, & Brown JM (1997). The reliability of Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58, 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]