Abstract

Emphysematous cystitis (EC) is a rare condition characterized by gas within the bladder wall or lumen. EC is most commonly seen in elderly women with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (DM). Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are most commonly implicated. We present a 68-year-old woman with poorly controlled DM who presented with altered mental state with growth of Candida glabrata in urine and blood cultures. CT abdomen and pelvis revealed air in the bladder lumen and the extraperitoneal space. Bladder rupture was suspected and bladder decompression was managed conservatively with a foley catheter.

1. Introduction

Emphysematous cystitis (EC) is a rare condition whose hallmark is the presence of gas within the bladder wall or lumen.1 It is considered a complication of urinary tract infections (UTI) and possesses similar risk factors to UTIs. These risk factors include a neurogenic bladder, diabetes mellitus (DM), recurrent UTIs, urinary outflow obstruction, indwelling catheters, and immune deficiency.1,2 DM is the greatest risk factor for EC, and the classic patient is an elderly female with poorly controlled DM. Historically, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae predominantly account for most infections in patients with EC, making up 60% and 10–20% of urine cultures respectively. The clinical manifestations of EC vary widely and can range from symptoms of a mild UTI to full septic shock and peritonitis.3,4 To the best of our knowledge, this case is the first documented case of Candida glabrata as the causative organism.

2. Case presentation

A 68-year-old female with poorly controlled DM presented to the ED with altered mental status for the duration of 4 days. Upon evaluation by emergency medical services, she was unresponsive with a blood sugar of 498 and promptly transported to our institution. She had a past medical history significant for type 2 DM, peripheral artery disease, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, mesenteric ischemia, gastroparesis, fibromyalgia, a stenting procedure, and vascular graft.

On initial evaluation in the emergency department, she was tachycardic with a heart rate of 169, hypotensive to 86/45, tachypneic to 46 with an oxygen saturation of 92%. Lab tests revealed the follow abnormalities: WBC of 19.4 thous/mm3, Na 129 Meq/dL, Cl 92 Meq/dL, creatinine 3.63mg/dL, Co2 10 Meq/L, CRP 40.2 mg/dL, ESR 70mm/hr, glucose 719 mg/dL, and lactic acid 3.6 mmol/L. Urinalysis revealed abnormally turbid urine with glucose >1000, WBCs 10–20, RBCs 5–10, 4+ bacteria, and TNTC of yeast. Urine and blood cultures from day of admission ultimately grew Candida glabrata and IV micafungin and cefepime were initiated.

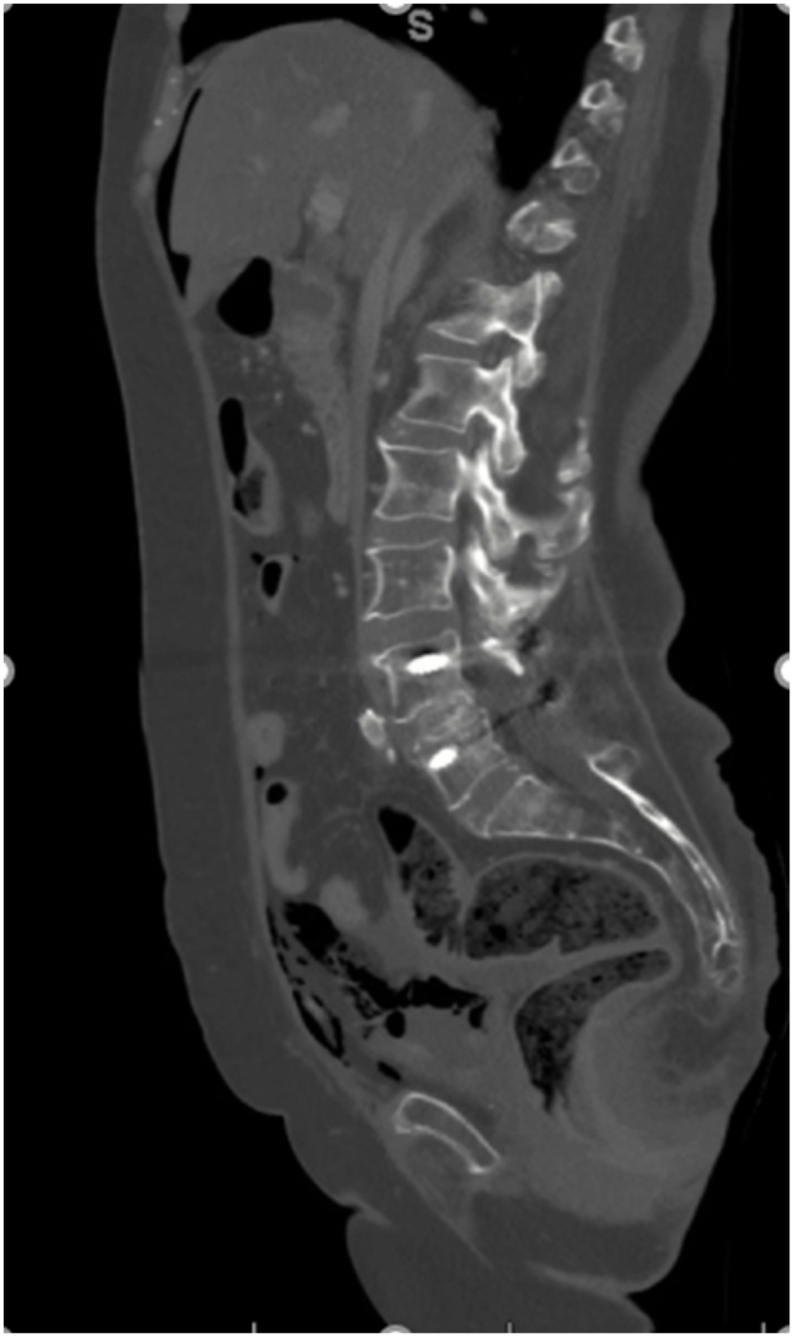

Upon admission, DKA protocol was implemented. Due to the absence of ketones in the patient's urine, she was ultimately found to have hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. A CT abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2.) revealed a large amount of free air in the extraperitoneal space which raised concerns of an extraperitoneal bladder perforation. Given her clinical instability, surgical intervention was deferred, and her suspected bladder perforation was managed conservatively with foley catheter placement to decompress the bladder. Patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and intubated the following day. The patient was extubated five days later and transferred to the hospitalist service. The following day, she developed hypoxia, tachypnea, and hypertension. Her ABG showed her Pa. O2 in the 40's, and she was subsequently reintubated. Heparin was initiated as she was suspected of having a pulmonary embolus. She developed a fever and was intermittently tachycardic during her stay, and she required a tracheostomy and pressure support. After a 22 day stay, her goals of care were discussed with her family who decided to transition to comfort care. She passed later the same day due to multiorgan and respiratory failure and cardiac arrest.

Fig. 1.

CT abdomen/pelvis sagittal view demonstrating free air in extraperitoneal space.

Fig. 2.

CT abdomen/pelvis axial view demonstrating visible air overlying the liver.

3. Discussion

The typical patient that presents with EC is an elderly diabetic woman.2 The prevalence of DM in patients with EC is 62.2% compared to 8.6% in people over 20 years old in the general population. The symptoms of EC vary widely and are non-specific with abdominal pain found in 80% of patients and gross hematuria in 60%.1 Pneumaturia is a specific symptom that is seen in 70% of patients with recent instrumentation, but it proves to be a rare patient complaint. The mechanism behind the development of EC is not well understood, but it is thought that the high concentration of glucose plays a role in the development of pneumaturia.2 When glucose concentrations are high, as in patients with DM, the available carbohydrates allow for pathogens to produce carbon dioxide through fermentation. Impaired tissue perfusion combined with high glucose and gas producing pathogens allows for the development of EC.4 Although EC mainly affects patients with DM, it can also be found in those without DM as well. The mechanism behind EC in non-diabetics is thought to be the result of tissue proteins and urinary albumin being used as substrates in addition to poor tissue perfusion.2,4 EC can also be due to colovesicular fistula (CVF) which presents with pneumaturia 70–90% of the time.5 CVF occurs due to high intraluminal pressure creating outpouchings in weak areas of the mucosa/submucosa of the sigmoid colon most commonly secondary to diverticulitis.

Radiographic imaging is required to confirm the diagnosis.1,3 Plain abdominal radiographic imaging is commonly used but computed tomography is the most sensitive tool for establishing a diagnosis of EC. In cases of EC, radiographic studies demonstrate “curvilinear areas of increased radiolucency” along the bladder wall.1 The bladder wall may also demonstrate a “beaded necklace appearance.” This is due to an irregular thickening of the mucosal surface. In 90% of cases, non-surgical interventions such as antibiotics, glycemic control, addressing any underlying disorders, and bladder drainage are successful in treating EC.1,4 In 10% of cases, surgical intervention is needed. Surgical interventions may include debridement and partial or total cystectomy.4 Additionally, the mortslity rate for patients with EC has been estimated to be around 7%.1

4. Conclusion

EC is a rare but serious complication of a UTI most commonly affecting diabetic patients that presents with pneumaturia and non-specific physical complaints. Its clinical presentation ranges widely from an asymptomatic case found incidentally, to septic shock and a perforated bladder as seen in our case. Clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion as EC can lead to sepsis and death if not detected early in its course.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT author statement

Viktoriya Sapkalova: conceptualization, investigation, resources, writing – original draft, Samantha Zhan-Moodie: writing – review and editing, project administration, Michael Oberle: conceptualization, supervision, Martha K. Terris: conceptualization, supervision.

Section headings

Inflammation and infection, oddities.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Viktoriya Sapkalova, Email: vsapkalova@augusta.edu.

Samantha Zhan-Moodie, Email: SZHANMOODIE@augusta.edu.

References

- 1.Amano M., Shimizu T. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of the literature. Intern Med. 2014;53(2):79–82. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eken A., Alma E. Emphysematous cystitis: the role of CT imaging and appropriate treatment. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(11-12):E754–E756. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronald A., Ludwig E. Urinary tract infections in adults with diabetes. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17(4):287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukendi A.M. Emphysematous cystitis: a case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8(9):1686–1688. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeras K., Qasawa R.N., Akbar H., et al. StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan. Colovesicular Fistula. [Updated 2021 Aug 9]. in: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL)https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518990/ Available from: [Google Scholar]