Abstract

Objective:

The aim is to study the trends of lymphosarcoma incidence in the regional context in Kazakhstan.

Methods:

The retrospective study was done using descriptive method of oncoepidemiology. The extensive, crude and age-specific incidence rates are determined according to the generally accepted methodology used in statistics. The data were used to calculate the average percentage change (APС) using the Joinpoint regression analysis to determine the trend over the study period.

Results:

3,987 new cases of lymphosarcoma were registered in the country (50.7% in men, 49.3% in women). During the studied years the average age of patients was 54.2±0.8 years. The highest incidence rates per 100,000 in the entire population were found in the age groups 65-69 years (10.4±0.6), 70-74 years (10.7±0.8), and 75-79 years (10.3±0.8). The highest tendency to increase in age-related incidence rates was at the age over 85 (APC=+8.26) and to decrease at the age under 30 (APC=−6.17). The average annual standardized incidence rate was 2.3 per 100,000, and in dynamics tended to increase (APC=+1.43). It was found that the downward trend was observed in five regions (Akmola, Atyrau, Karaganda, North and South Kazakhstan), and the most pronounced decline was in the Karaganda (APC=−3.61) and South Kazakhstan (APC=−2.93) regions. When compiling thematic maps, incidence rates were determined based on standardized indicators: low – up to 1.97, average – from 1.97 to 2.60, high – above 2.60 per 100,000 for both sexes.

Conclusion:

Trends in the incidence of lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan are growing and have geographical variability, and a high incidence is observed in the eastern and northern regions of the country. Sex differences have been established the incidence in men is higher than in female population, but the rate of increase in the incidence in women is more pronounced.

Key Words: Lymphosarcoma, incidence, trends, geographical variation, Kazakhstan

Introduction

Lymphosarcoma is the most common hematological malignant tumor worldwide, belongs to a diverse class of B- and T-cell proliferation. Lymphosarcoma covers more than 40 lymphoid malignancies of various molecular origin, differing in clinical picture and prognosis, which range from very indolent to very aggressive (Turner et al., 2010). According to the latest GLOBOCAN data, about 544,352 new cases of lymphosarcoma were diagnosed worldwide in 2020, accounting for 2.8% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide (Ferlay et al., 2022).

The incidence varies in countries with high and low human development index. The largest proportion of patients (about 82.2%) is registered in countries with a high (178,556 cases) and very high (268,797 cases) human development index (Ferlay et al., 2022).

The etiology and risk factors for the development of lymphosarcoma are gene rearrangement (Nachmias et al., 2019), chromosome translocation (Chiu and Blair, 2009), and viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (Muncunill et al., 2019), human immunodeficiency virus (Song et al., 2020; Hinkle et al., 2020), hepatitis B/C virus (Zhu et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020), helicobacter pylori (Smedby and Ponzoni, 2017) and human herpes virus (Cho et al., 2015) infection.

In most cases, patients with lymphosarcoma have persistent painless lymphadenopathy, and another part of patients also have constitutional symptoms, in particular profuse night sweats, persistent fever and unexplained weight loss (Ansell, 2015). The accuracy of lymphosarcoma diagnosis requires excision biopsy followed by examination by a pathologist and final classification based on morphology, immunophenotype, genetic and clinical features (McKay et al., 2016). Optimal management of patients depends on an accurate pathological diagnosis, the exact stage of the disease and the identification of adverse risk factors.

Early studies of the incidence of malignant neoplasms of blood and lymphoid tissue in the population of Kazakhstan revealed a high incidence of these pathologies (Igissinov et al., 2014; Bekmukhambetov et al., 2015; Mamyrbayev et al., 2016; Gabbsova and Dushpanova, 2019). It is estimated that 445 new cases of lymphosarcoma were diagnosed in Kazakhstan in 2020, which is 1.3% of cancer diagnoses (the twentieth most common cancer diagnosis) (Ferlay et al., 2022). Kazakhstan has not previously conducted studies studying the temporal trends and geographical distribution of the incidence of lymphosarcoma. Knowledge of the temporal and spatial coordinates of the disease is the basis for the development of hypotheses and conducting proper studies of its determinants.

Materials and Methods

Cancer registration and patient recruitment

The cancer registry of the population of Kazakhstan covers considering the administrative-territorial division. New cases of lymphosarcoma were extracted from the reporting forms of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan (form 7 and form 35) from 2010 to 2019 using the International Disease Code 10, code C82-85.

Population denominators

Population denominators for calculation of incidence rates were provided by the Bureau of National Statistics. At the same time, data on the number of populations of the republic, taking into account the studied regions, are used, all data are presented on the official website (Bureau of National Statistics, 2022).

Statistical analysis

The main method used in the study of incidence was a retrospective study using descriptive and analytical methods of oncoepidemiology. ASRs were calculated for eighteen different age groups (0-4, 5-9, …, 80-84, and 85+) using the world standard population proposed by WHO (Ahmad et al., 2001) with recommendations from the National Cancer Institute (2013).

The extensive, crude rate (CR), age-standardized rate (ASR) and age-specific incidence rates (ASIR) are determined according to the generally accepted methodology used in sanitary statistics. The annual averages (M, P), mean error (m), Student criterion, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. We were not smoothing the main calculation formulas in this paper, since they are detailed in the methodological recommendations and textbooks on medical and biological statistics (Merkov and Polyakov, 1974; Glanz, 1999; dos Santos Silva, 1999). The incidence trend was studied for 10 years, while the incidence trend was determined by the least squares method and using the Joinpoint program (https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/). The data were used to calculate the average percentage change (APС) using the Joinpoint regression analysis. When compiling thematic maps, crude rates and ASRs were used for 10 years (2010-2019). The method of compiling a thematic map proposed in 1974 by S.I. Igissinov (Igissinov, 1974) was used, based on the determination of the standard deviation (σ) from the average (x).

Viewing and processing of the received materials was carried out using the Microsoft 365 software package (Excel, Word, PowerPoint), in addition, online statistical calculators were used (https://medstatistic.ru/calculators/averagestudent.html), where Student criterion was calculated when comparing the average values.

Ethics approval

The study included an analysis of publicly available administrative data and did not involve contacts with individuals. The Local Ethics Commission of the Central Asian Institute for Medical Research approved this study.

Results

In 2010-2019, 3,987 new cases of lymphosarcoma were registered in the country, of which 2,023 cases (50.7%) among men and 1,964 cases (49.3%) among women. The distribution of age groups by the number of new cases of lymphosarcoma showed that the groups aged 50 to 69 years were the most numerous – 1,914 (48.0%) (Table 1). The proportion of new cases of lymphosarcoma among the male population by age group (50-69 years – 48.7%) was similar to the distribution among both sexes, but among the female population a significant proportion of cases occur in the age group 55-74 years (47.6%).

Table 1.

Number and Age-Specific Incidence Rate of Lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

| Age | All | Male | Female | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Incidence | Number (%) | Incidence | Number (%) | Incidence | |||||||

| per 100,000 | APC | R2 | per 100,000 | APC | R2 | per 100,000 | APC | R2 | ||||

| < 30 | 473 (11.9) | 0.5±0.0 | −6.17 | 0.5980 | 281 (13.9) | 0.6±0.1 | −6.91 | 0.5497 | 192 (9.8) | 0.4±0.0 | −4.96 | 0.2862 |

| 30-34 | 152 (3.8) | 1.1±0.1 | −1.95 | 0.0510 | 71 (3.5) | 1.0±0.1 | −2.86 | 0.1495 | 81 (4.1) | 1.2±0.1 | −1.23 | 9.00E-05 |

| 35-39 | 189 (4.7) | 1.5±0.2 | +1.76 | 0.0391 | 98 (4.8) | 1.6±0.2 | −2.58 | 0.0294 | 91 (4.6) | 1.5±0.2 | +6.61 | 0.2569 |

| 40-44 | 236 (5.9) | 2.1±0.1 | +4.42 | 0.3892 | 136 (6.7) | 2.5±0.2 | +4.27 | 0.2704 | 100 (5.1) | 1.7±0.2 | +4.38 | 0.1029 |

| 45-49 | 254 (6.4) | 2.4±0.1 | −0.19 | 0.0015 | 137 (6.8) | 2.7±0.2 | −1.87 | 0.0535 | 117 (6.0) | 2.1±0.2 | +2.24 | 0.0880 |

| 50-54 | 422 (10.6) | 4.1±0.2 | +2.20 | 0.2273 | 229 (11.3) | 4.8±0.2 | +0.74 | 0.0219 | 193 (9.8) | 3.6±0.3 | +3.98 | 0.2443 |

| 55-59 | 515 (12.9) | 6.0±0.2 | −0.11 | 0.0056 | 257 (12.7) | 6.7±0.3 | −2.14 | 0.2076 | 258 (13.1) | 5.4±0.3 | +1.76 | 0.0723 |

| 60-64 | 534 (13.4) | 8.1±0.5 | +2.91 | 0.2632 | 267 (13.2) | 9.6±0.7 | +0.59 | 0.0240 | 267 (13.6) | 7.0±0.7 | +4.24 | 0.2333 |

| 65-69 | 443 (11.1) | 10.4±0.6 | +2.08 | 0.1792 | 232 (11.5) | 13.9±1.0 | −1.17 | 0.0020 | 211 (10.7) | 8.0±0.7 | +5.82 | 0.5021 |

| 70-74 | 343 (8.6) | 10.7±0.8 | +1.67 | 0.0375 | 144 (7.1) | 12.3±1.4 | +1.37 | 0.0027 | 199 (10.1) | 9.8±0.6 | +2.28 | 0.1016 |

| 75-79 | 268 (6.7) | 10.3±0.8 | +5.03 | 0.5223 | 118 (5.8) | 13.8±1.2 | +6.01 | 0.4481 | 150 (7.6) | 8.5±0.9 | +3.97 | 0.2935 |

| 80-84 | 116 (2.9) | 8.3±1.1 | +7.87 | 0.4306 | 40 (2.0) | 9.6±1.0 | +3.97 | 0.1459 | 76 (3.9) | 7.8±1.5 | +8.65 | 0.3149 |

| 85+ | 42 (1.1) | 5.3±1.1 | +8.26 | 0.1516 | 13 (0.6) | 6.7±1.8 | −6.07 | 0.0640 | 29 (1.5) | 4.8±1.1 | +10.0 | 0.4142 |

| CR | 3987 (100.0) | 2.3±0.1 | +1.92 | 0.5068 | 2023 (100.0) | 2.4±0.1 | +0.19 | 0.0029 | 1964 (100.0) | 2.2±0.1 | +4.07 | 0.7235 |

| ASR | − | 2.3±0.1 | +1.43 | 0.3311 | − | 2.8±0.1 | −0.34 | 0.0196 | − | 2.0±0.1 | +3.37 | 0.6241 |

| Average Age | − | 54.2±0.8 | +1.11 | 0.7216 | − | 52.5±0.8 | +1.18 | 0.6540 | − | 55.9±0.8 | +0.92 | 0.5947 |

APC, average percentage change. R2, the value of the approximation confidence; CR, crude rate; ASR, age−standardized rate

The average age of patients with lymphosarcoma had an upward trend from 51.3±1.1 years (95%CI=49.1-53.5) in 2010 to 56.5±0.8 years (95%CI=55.0-58.0) in 2019, and the average age of patients was 54.2±0.8 years (95%CI=52.6-55.7) (APC=+1.11) (Table 1). The average age of female patients is 3 years older than the average age of male patients; the differences are statistically significant (p=0.003).

The highest incidence rates per 100,000 in the entire population were found in the age groups 65-69 years (10.4±0.6), 70-74 years (10.7±0.8), and 75-79 years (10.3±0.8) (Figure 1). At the same time, the highest incidence rates per 100,000 population among females were in 70-74 years, and among males in 65-69 years.

Figure 1.

ASIR of Lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

The incidence of lymphosarcoma tended to decrease in four age groups: under 30 years (APC=−6.17), 30-34 years (APC=−1.95), 45-49 years (APC=−0.19) and 55-59 years (APC=−0.11). In other age groups, the incidence of lymphosarcoma increased, with the most pronounced APC observed in the age groups of 75-79 years (APC=+5.03), 80-84 years (APC=+7.87), 85+ years (APC=+8.26) (Table 1). Age-specific incidence rates in female patients had a downward trend only in the age groups under 30 years (APC=−4.96) and 30-34 years (APC=−1.23). While ASIR in male patients had a downward trend in 7 age groups out of thirteen (and the biggest decline was at the age of under 30 years and over 85 years) (Table 1).

ASIR per 100,000 had regional characteristics: almost all regions have a predominantly bimodal increase in incidence (Figures 2A and 2B). During the study period, there are no cases of lymphosarcoma in the age groups of 80-84 years and 85+ years in Atyrau and Kyzylorda regions, and in the Aktobe region in 80-84 years. A unimodal increase in morbidity was found in such regions as Almaty (70-74 years) and Pavlodar (75-79 years), as well as in the city of Astana (65-69 years) (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2A.

Age-Specific Incidence Rate of Lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Figure 2B.

Age-Specific Incidence Rate of Lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Crude rates of lymphosarcoma incidence per 100,000 tended to increase from 1.9±0.1 (95%CI=1.7-2.1) (2010) to 2.5±0.1 (95%CI=2.3-2.7) in 2019, the average was 2.3±0.1 (95%CI=2.2-2.4) (APC=+1.92). The standardized incidence rate for the study period in the male population was 2.8±0.1 per 100,000 (APC=−0.34) (Figure 3A), and in the female population was 2.0±0.1 per 100,000 (APC=+3.37) (Figure 3B). Age – standardized incidence rate for both sex was 2.3±0.1 per 100,000 population (APC=+1.43) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3A.

Trend of Lymphosarcoma Incidence in the Male Population in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Figure 3B.

Trend of Lymphosarcoma Incidence in the Female Population in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Figure 3C.

Trend of Lymphosarcoma Incidence in Both Sex in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Based on the calculated average annual ASR lymphosarcoma indicators, the thematic maps were compiled. The incidence by region among the male and female population had some differences. At the same time, both men and women had the highest incidence rates in the central and eastern regions (Figure 4A and 4B). The levels of lymphosarcoma ASR for both sexes per 100,000 based on the following criteria were determined: low – up to 1.97, average – from 1.97 to 2.60, high – above 2.60. As a result, the following groups of regions were revealed (Figure 4C):

Figure 4.

Thematic Map of Lymphosarcoma Incidence (ASR) in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019. A, The geographical distribution of cancer incidence (average of 10 years) for male); B, The geographical distribution of cancer incidence (average of 10 years) for female); C, The geographical distribution of cancer incidence (average of 10 years) for both sex)

1. Regions with the lowest indicators (up to 1.97 per 100,000): Mangystau (1.26), Atyrau (1.36), Almaty (1.51), Kyzylorda (1.53), South Kazakhstan (1.87).

2. Regions with average indicators (from 1.97 to 2.60 per 100,000): Zhambyl (2.02), Aktobe (2.17), West Kazakhstan (2.34), Akmola (2.36).

3. Regions with high indicators (2.60 and above per 100,000): Pavlodar (2.72), East Kazakhstan (2.73), Almaty city (2.79), North Kazakhstan (2.85), Astana city (2.88), Karaganda (3.02), Kostanay (3.12).

According to the thematic map, the highest incidence rates of lymphosarcoma belong to the northern, eastern and central regions of the country. The southern regions belong to the regions with low indicators.

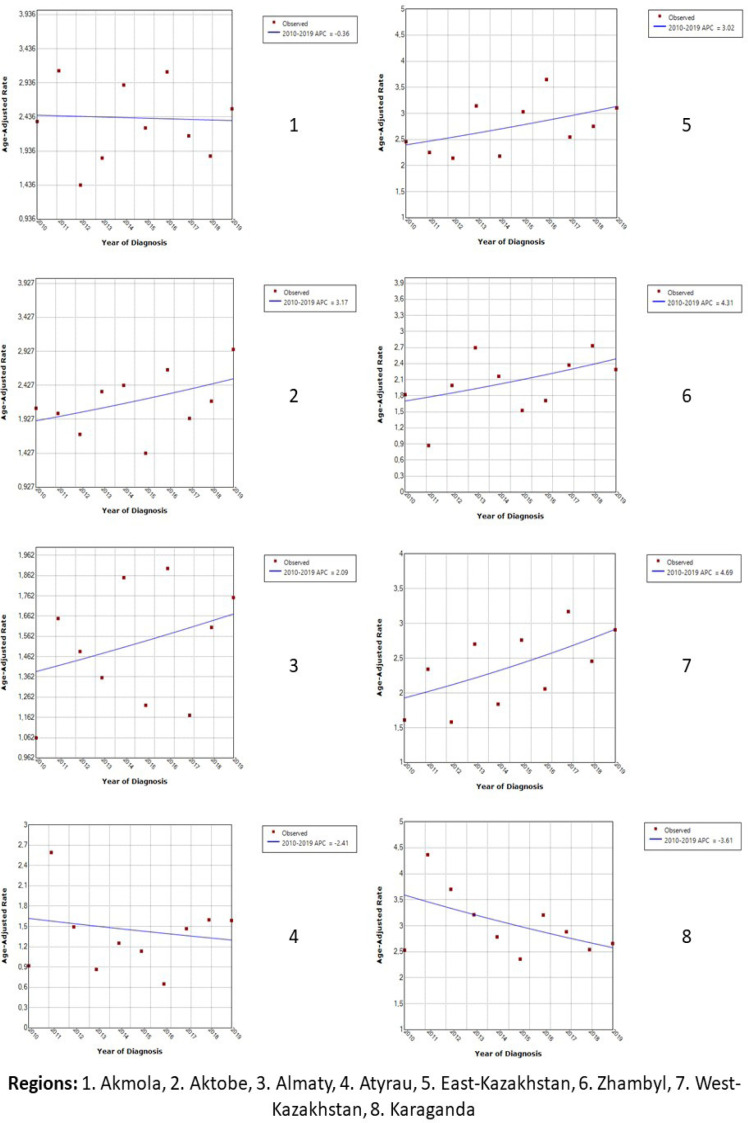

Analyzing the average annual growth of ASR, it was found that the downward trend was observed in five regions (Akmola, Atyrau, Karaganda, North and South Kazakhstan), and the most pronounced decline was in the Karaganda (APC=−3.61) and South Kazakhstan (APC=−2.93) regions (Figure 5A and 5B). In all other regions, the ASR tended to increase. The highest growth rate was found in the city of Astana (APC=+5.60), and the lowest in the Almaty region (APC=+2.09).

Figure 5A.

Trends of Age-Standardized Incidence Rates of Lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Figure 5B.

Trends of Age-Standardized Incidence Rates of Lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan, 2010-2019

Discussion

This study presents for the first time generalized data on all forms of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which were presented in a combined format in the range C82-85. Kazakhstan belongs to the regions with a low incidence of lymphosarcoma. The same incidence rates were found in countries such as Benin, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Bolivia and Bangladesh (Ferlay et al., 2022).

At the global level, the incidence of lymphosarcoma gradually increased from 4.75 per 100,000 people in 1990 to 6.18 per 100,000 in 2017 (Sun et al., 2022). The incidence of lymphosarcoma in Kazakhstan is also increasing, and the indicator for the study period increased by 32%. However, the incidence trend varied from region to region. It can be assumed that the observed heterogeneity of the incidence of lymphosarcoma in the regional aspect is due to the imperfection of cancer care and the availability of diagnostic tools, as well as the prevalence and distribution of underlying known and suspected risk factors.

The incidence of lymphosarcoma is steadily increasing with age. Since age is a strong negative factor in all subtypes of lymphosarcoma. According to a study by Thandra and others, the average age of registered patients with lymphosarcoma in the world is 67 years old and 57% of all patients are over 65 years old (Thandra et al., 2021). And in Kazakhstan, the average age of diagnosis was 54 years, while 67% of diagnoses were made to people over 50 years old. Despite the high growth rates in the older age groups, the degree of approximation was expressed only in the group of 75-79 years. It should be noted that in some regions (Atyrau, Kyzylorda and Aktobe), not a single case was registered in the age groups of 80 years and older, which is related to the issues of accounting and registration of cancer patients.

Worldwide, men have a cumulative lifetime risk of developing lymphosarcoma more than twice as high (Thandra et al., 2021). Accordingly, the incidence of lymphosarcoma in men was higher than in women. Moreover, in the world, the sex ratio varied from 1.1 to 1.8 depending on the region (Miranda-Filho et al., 2019). Such a ratio, namely about 1.4, was also revealed in our country. However, if we consider the trends of incidence in Kazakhstan, the incidence in men is decreasing, and in women, on the contrary, it is increasing.

Many factors unrelated to etiological ones, such as a change in classification, an increase in the accuracy of histological diagnostics, a wider use of immunohistochemical techniques, and possibly a change in the principles of morbidity registration, could have a certain impact on statistics, but they are insufficient to explain the situation as a whole.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are a common collective name of a clinically, morphologically, immunophenotypically and cytogenetically very diverse group of lymphomas, including all lymphomas except “Hodgkin’s lymphoma”, and this should be taken into account for a more detailed analysis and hypotheses about risk factors and the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships at the regional and national levels. Of scientific and practical interest is the epidemiological study of the links of the above differences with racial differences, ethnic characteristics and socio-economic status.

The advantage of this study is that it is the first in Kazakhstan, which is spatio-temporal assessment of the incidence of lymphosarcoma at the national and regional levels. At the same time, comprehensive population information on the main patterns of lymphosarcoma incidence is necessary not only to substantiate etiological hypotheses and plan future medical services, but also to monitor ongoing diagnostic and antitumor measures, which requires further targeted and in-depth research.

Author Contribution Statement

FB, ZhT: Collection and preparation of data, primary processing of the material and their verification; FB, AS: Statistical processing and analysis of the material, writing the text of the article (material and methods, results); RR, FB, TD: Writing the text of the article (introduction, discussion); NI, ZB: Concept, design and control of the research, approval of the final version of the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the contribution of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Republic of Kazakhstan to the current research by providing the data. This study was not funded, it was performed within the framework of the Farkhat Bayembayev’s dissertation, the topic of the dissertation was approved at the University Council of Astana Medical University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad OE, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. Age standardization of rates: a new who standard, 2001. GPE Discussion Paper Series: No.31 EIP/GPE/EBD. World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell SM. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1152–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekmukhambetov Y, Mamyrbayev A, Jarkenov T, Makenova A, Imangazina Z. Malignant Neoplasm Prevalence in the Aktobe Region of Kazakhstan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:8149–53. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.18.8149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from official website of the: https://stat.gov.kz, authors. Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2022.

- Chiu BC, Blair A. Pesticides, chromosomal aberrations, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Agromed. 2009;14:250–5. doi: 10.1080/10599240902773140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SF, Wu WH, Yang YH, et al. Longitudinal risk of herpes zoster in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma receiving chemotherapy: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14008. doi: 10.1038/srep14008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbsova ST, Dushpanova AТ. Epidemiology of lymphomas in Kazakhstan Distinctive features of the epidemiology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Vestnik KazNMU. 2019;2:332–6. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz S (Russian), authors . Biomedical statistics. Moscow: Practice; 1998. p. 459 . [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle C, Makar G, Brody J, et al. HIV-associated “Double-Hit” lymphoma of the tonsil: a first reported case. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:1129–33. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01135-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igissinov N, Kulmirzayeva D, Moore MA, et al. Epidemiological assessment of leukemia in Kazakhstan, 2003- 2012. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6969–72. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.16.6969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igissinov SI. Preparation and application method of cartograms in oncology. Healthcare Kazakhstan. 1974;2:69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Lee Y, Park B, et al. Hepatitis virus B and C infections are associated with an increased risk of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma: a nested case‐control study using a national sample cohort. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1214–20. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamyrbayev A, Dyussembayeva N, Ibrayeva L, et al. Features of Malignancy Prevalence among Children in the Aral Sea Region. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:5217–21. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2016.17.12.5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay P, Fielding P, Gallop-Evans E, et al. Guidelines for the investigation and management of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:32–43. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkov AM, Polyakov LY. Health Statistics. Leningrad: Medicine; 1974. p. 384. (Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Filho A, Piñeros M, Znaor A, et al. Global patterns and trends in the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30:489–99. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muncunill J, Baptista MJ, Hernandez-Rodriguez A, et al. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus load as an early biomarker and prognostic factor of human immunodeficiency virus-related lymphomas. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:834–43. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias B, Sandler V, Slyusarevsky E, et al. Evaluation of cerebrospinal clonal gene rearrangement in newly diagnosed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol. 2019;98:2561–7. doi: 10.1007/s00277-019-03798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Recommendations on the use of the World Standard (WHO 2000-2025) (cited 2022 Nov 03) 2013. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/world.who.html.

- Online Statistical Calculator. https://medstatistic.ru/calculators/averagestudent.html .

- Smedby KE, Ponzoni M. The aetiology of B-cell lymphoid malignancies with a focus on chronic inflammation and infections. J Intern Med. 2017;282:360–70. doi: 10.1111/joim.12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Bassig B, Bender N, et al. Associations of viral seroreactivity with AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2020;36:381–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2019.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Xue L, Guo Y, et al. Global, regional and national burden of non-Hodgkin lymphoma from 1990 to 2017: estimates from global burden of disease study in 2017. Ann Med. 2022;54:633–45. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2039957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, et al. Epidemiology of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Med Sci (Basel) 2021;9:5. doi: 10.3390/medsci9010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JJ, Morton LM, Linet MS, et al. InterLymph hierarchical classification of lymphoid neoplasms for epidemiologic research based on the WHO classification (2008): update and future directions. Blood. 2010;116:e90–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jing L, Li X. Hepatitis C virus infection is a risk factor for non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98:e14755. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]