Abstract

Context:

A central premise of the literature on healthcare quality is that improving the quality of care will lead to improvements in health outcomes. A systematic review was conducted to better inform quality improvement efforts in the area of family planning. The objective of this systematic review is to update a previous review focused on the quality of family planning services, namely, the impact of quality improvement efforts and client perspectives about what constitutes quality family planning services. In addition, this review includes new literature examining provider perspectives.

Evidence acquisition:

Multiple databases from January 1985 through January 2015 were searched within the peer-reviewed literature that described the quality of family planning services. The retrieval and inclusion criteria included full-length articles published in English, which described studies occurring in a clinic-based setting to include family planning services.

Evidence synthesis:

Search strategies identified 16,145 articles, 16 of which met the inclusion criteria. No new intervention studies addressing the impact of quality improvement efforts on family planning outcomes were identified. Sixteen articles provided information relevant to client or provider perspectives about what constitutes quality family planning services. Clients and providers mostly identified the need for services that were accessible, client-centered, and equitable. Themes related to effectiveness, efficiency, and safety were mentioned less frequently.

Conclusions:

Family planning services that account for both patient and provider perspectives may be more effective. Further research is needed to examine the impact of improved quality on provider practices, client behavior, and health outcomes.

Context

The U.S. faces numerous reproductive health challenges—half of all pregnancies are unintended, more than 700,000 teens give birth each year, and many poorly spaced births contribute to poor infant health outcomes such as preterm birth.1,2 Quality is a critical component in the provision of all clinical services, including family planning. The definition of healthcare quality can vary but generally refers to the degree to which services are provided in an appropriate manner and achieve the desired outcomes.3-5 A central premise of the literature on quality is that improving the quality of health care will lead to improvements in health outcomes.

IOM has dedicated more than a decade to better understanding how healthcare quality can be improved, beginning with the reports To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System6 and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.3 In 2001, IOM identified six dimensions of healthcare quality that have been critical in guiding understanding in the area (Table 1).3

Table 1.

IOM’s Six Dimensions of Healthcare Quality3

| Dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Accessible | The timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes. |

| Client-centered | Care is respectful of, and responsive to, individual client preferences, needs, and values, and client values guide all clinical decisions. |

| Effective | Services are based on scientific knowledge and provided to all who could benefit, and are not provided to those not likely to benefit. |

| Efficient | Waste is avoided, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy. |

| Equitable | Care does not vary in quality because of the personal characteristics of clients such as age, gender, ethnicity, residence, insurance status, and SES. |

| Safe | Avoids injury to clients from the care that is intended to help them. |

Although there is a body of research demonstrating the impact of quality improvement efforts in other health areas,7,8 little evidence is available to confirm the association between quality improvements and health outcomes in the family planning setting. Becker et al.9 examined this question through a systematic review of 29 studies published between 1985 and 2005 related to family planning service quality in the U.S. Results showed that several facility characteristics were correlated with higher quality ratings, including private facility or provider, female provider, and non-physician provider. Those studies also reported several client factors associated with poorer quality ratings, including unmarried, less than a college education, racial/ethnic minorities, Spanish speaker, and male gender. Twelve studies identified by Becker and colleagues examined the relationship between quality and some reproductive health outcomes. These studies tended to report positive associations between service quality and contraceptive use as well as satisfaction with contraceptive method; however, a few studies found limited (e.g., effects disappearing by 12 months) or no effects. Finally, eight studies in the review examined client preferences regarding the quality of family planning services they receive. Becker et al. concluded that the most important aspects reported through these studies were personalized attention, time spent with provider, continuity of care (e.g., seeing the same provider), and receiving technically appropriate and affordable care. Other identified factors, though considered less important, were related to convenience of services such as wait times and weekend hours.

As indicated by Becker and colleagues,9 much of what is known about quality in the provision of family planning services focuses on the association with reproductive health outcomes. Less is known about what clients and providers perceive as quality family planning services, and the extent to which these perceptions are consistent with the dimensions of healthcare quality as defined by IOM.3 This systematic review updates the previous review of Becker et al.9 and also includes a focus on provider perspectives of family planning quality, which was not a primary focus of the previous review. Updated systematic review findings in the area are critical to informing what constitutes quality family planning services as well as quality improvement strategies in this area. The findings of this review were used to help further inform the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) and CDC in their efforts to develop the clinical recommendations, “Providing Quality Family Planning Services.”10

Evidence Acquisition

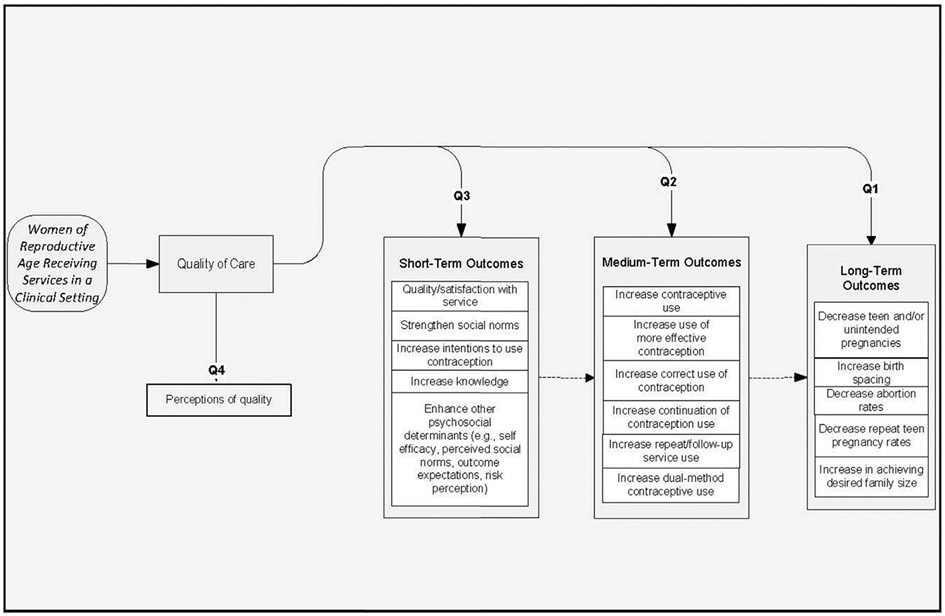

This review followed a similar methodology as the other reviews in this series, which is detailed elsewhere.11 Briefly, the review of the evidence was a multistep process that began with the development of four key questions (Table 2) and an analytic framework (Figure 1) to show the relationships between the key questions. The first three questions focused on the relationship between quality family planning services and short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes. The last key question focused on client and provider perspectives regarding what constitutes quality family planning services. Search strategies were developed that included the identification of search terms (Appendix A), which were applied to several electronic databases (Appendix B).

Table 2.

Key Questions

| Key question no. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Is there a relationship between providing quality family planning service and improved long-term outcomes? |

| 2 | Is there a relationship between providing quality family planning service and improved medium-term outcomes? |

| 3 | Is there a relationship between providing quality family planning service and improved short-term outcomes? |

| 4 | What are client and provider perspectives regarding what constitutes quality family planning services? |

Figure 1.

Analytic framework for the systematic review on family planning service quality.

Selection of Studies

Searches to inform OPA and CDC recommendations were conducted in 2011 and included articles published from January 1985 through February 2011. An updated search was conducted in January 2015 to identify any additional studies published since the initial searches were conducted (findings from the updated search are presented at the end of the evidence synthesis section). Retrieval and inclusion criteria were developed a priori and applied to the search results. Retrieval criteria were used to initially screen titles and abstracts of articles for relevance. If an article was found to be relevant, the full-text article was retrieved and inclusion criteria were applied. The retrieval and inclusion criteria used in the development of this systematic review were as follows: published between January 1, 1985, and February 28, 2011; published in the English language; all articles were full-length; article must describe a study that occurred in a clinic-based setting where family planning services were provided; article must address at least one key question; and if the same study is reported in multiple publications, the most complete publication will be the primary reference.

Compared to the previous review conducted by Becker and colleagues,9 no new studies addressing the first three key questions were identified. However, several new studies describing patient and provider perspectives on quality family planning services were identified, which served as the focus of the remainder of this review. We summarized findings by categorizing client and provider preferences according to the six dimensions of quality that were defined by IOM.3 Owing to the descriptive nature of the included studies, no attempts were made to combine the results of the studies quantitatively (i.e., meta-analysis).

Evidence Synthesis

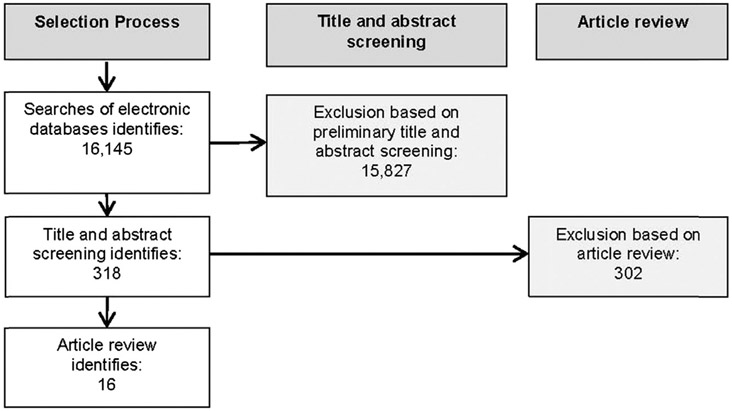

The evolution of the evidence base is presented in Figure 2. Sixteen articles were identified providing information related to client or provider perspectives regarding what constitutes quality family planning services and were included in this review.12-27 Of the 16 articles, six articles22-27 were included in the previous review conducted by Becker et al.9 (two additional studies28,29 included in Becker and colleagues9 were not able to be retrieved and thus are not reported here) and ten12-21 were new.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the systematic review process for perceptions of family planning service quality.

Table 3 presents a brief description of the main characteristics of the included studies, including the study design, study population, and data collection methods. Of the 16 studies, data were collected from both clients (k=14)12-17,20-27 and providers (k=4),18-21 with two studies20,21 including both clients and providers. In general, studies focused on client and provider self-perceptions of what constitutes quality family planning services; however, in some cases, providers reported basing their behaviors or practices on what they believe are their clients’ perceptions of quality family planning services. Six studies used primarily qualitative methods and ten used quantitative methods. A wide range of client ethnicities was presented in the studies. The few studies13,18,22,24,25 that provided socioeconomic information showed an emphasis on low-income participants. The sex of participants was almost exclusively focused on female clients and providers. Several studies15,17,18,20-22 included adolescents and presented findings by age group, but most12-14,16,19,23-26 did not.

Table 3.

Description of Study Design, Study Populations, and Data Collection

| Citation | Study design | Population | Data collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Becker et al. (1997)14 Funding source: The University of Texas at Austin |

Qualitative, in-depth interview |

Target population: Women with physical disabilities between the ages of 18 and 50 who could communicate in English Recruitment: Purposive sample of women through authors’ contacts (n=8), and by notices posted at local disability services (n=2) Sample: Ten women were interviewed Characteristics: Participants ranged from 28 to 47 years Physical disabilities: multiple sclerosis (n=2); cerebral palsy (n=2); paralysis resulting from spinal cord injury (n=2); arthritis (n=1); degenerative disk disorder (n=1); muscular dystrophy (n=1); cerebral palsy, arthritis, and fibromyalgia (n=1) All had some college education, were Caucasian, and worked or attended school Single (n=6); separated or divorced (n=3); married (n=1) |

Semi-structured interview guides were used by the 3 investigators; interviews were taped, transcribed, and analyzed using NUD*IST software. |

| Becker and Tsui (2008)13 Funding source: No information was provided |

Survey, by telephone |

Target population: Low-income women at risk of unintended pregnancy Recruitment: Used data from a nationally representative sample collected in 1995. Participants were selected from four sampling frames created from telephone exchanges in low-income areas (i.e., areas where at least 25% of households had an income below $15,000). Black and Latina women were oversampled. Sample: Eligible=2,054; enrolled=1,852 Characteristics: Race/ethnicity: white (n=454); black (n=451); and Latina (n=947) |

|

| Becker et al. (2009)12 Funding source: No information was provided |

Qualitative, in-depth interview |

Target population: Female clients of Title X-funded family planning services Recruitment: Two female interviewers visited two clinics on different days of the week at different hours, and approached as many women as possible who were seeking care or accompanying others to the clinic. Eligibility criteria were black, white, Latina, or a combination; aged 18 to 35 years; and report at least two visits to a health provider for family planning services in the previous 10 years. Sample: 40 were interviewed Characteristics: Race/ethnicity: English-speaking Latina (n=8); Spanish-speaking Latina (n=12); black (n=9); white (n=8); mixed (n=3) Age: 18–24 (n=20); 25–29 (n=9); 30–36 (n=10) Parity: 0 (n=20); 1 (n=7); 2 (n=7); ≥3 (n=6) Education: <high school (n=13); high school graduate (n=11); ≥college (n=16) Married (n=10); immigrant (n=17) |

Interviews were conducted at the clinics in private rooms; most immediately after the woman’s appointment. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were audiotaped if woman consented. $10 gift card as compensation. Taped interviews were transcribed, then coded by the investigator based on research questions. |

| Bender (1999)15 Funding source: University of Iceland, Klasi Ltd, Thorarensen Lyf Ltd. |

Survey (by mail) |

Target population: Adolescents and young adults Recruitment: Stratified random sample of 2,500 individuals aged 17 to 20 years from the Iceland Census in 1996; stratified by sex (80% female, 20% male) Sample: n=1,703 (68% response rate) Characteristics: Age: mean = 18.4 Gender: female (83.9%) Residence: Reykjavik area (58.9%) |

The survey was conducted by mail. A pamphlet about EC or a package of 10 condoms was provided as an incentive. Two attempts were made to contact non-respondents. |

| Chambers et al. (2002)20 Funding source: UK Department of Health, as part of a Health Action Zone Innovations project |

Qualitative |

Target population: Adolescents and young adults using reproductive health services, and providers of those services Recruitment: A database was composed of all providers of sexual health services to young people in the community, and then all providers were invited to a workshop; two mailed surveys were sent to all providers after the workshop. Young people were recruited by youth workers via word of mouth and flyers and then invited to a workshop; two mailed surveys were sent to all youth after the workshop Sample: 48 of 66 providers participated in the workshop; 66 and 56 of all providers responded to the first and second surveys, respectively. Fifty-five youth participated in the workshop; 18 and 14 of all youth responded to the first and second surveys, respectively Characteristics: Providers: male (26%) Youth: male (35%); age (12–20 years); attended school (n=38); unemployed (n=6) |

The workshop comprised brief plenary presentations followed by small group discussions. Surveys were based on the Delphi technique to identify areas of agreement. |

| Chetkovich et al. (1999)22 Funding source: No information was provided |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) |

Target population: Adolescents, young adults, and adults in need of family planning services Recruitment: Adult participants were recent AFDC recipients residing in three California counties. Adolescent/young adult participants were recruited through the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program in the three counties Sample: 12 adult and 7 adolescent groups of 4–10 participants were conducted (n=81 adults and 54 adolescent/young adults) Characteristics: Adult: 21–43 years; varying race/ethnicity, including African American (n=3 groups); English-speaking Latina (n=4 groups); Spanish-speaking Latina (n=3 group); white non-Latina (n=3 groups) Adolescent/young adult: 15–22 years who were pregnant and/or parenting; varying race/ethnicity, including African American (n=3 groups); English-speaking Latina (n=1 groups); Spanish-speaking Latina (n=1 group); white non-Latina (n=2 groups) |

Focus group guides were developed and used by facilitators. |

| Dixon-Woods et al. (2001)16 Funding source: Medisearch |

Qualitative (individual interviews) |

Target population: Women who receive reproductive health services Recruitment: Women who had been screened for chlamydia in one of two clinics in an urban area were approached and asked to participate in the study Sample: 37 participants Characteristics: Ages: 15–53 years Occupation: students (n=12); clerical/secretarial (n=4); homemakers (n=3); sales assistants (n=3); teachers (n=2); and other Race/ethnicity: black (n=3); white (n=34) |

Female clients were approached by an interviewer after she had been seen for services at the clinic. Interviews were carried out on-site, were tape recorded, and transcribed. |

| Fiddes et al. (2003)21 Funding source: No information was provided |

Survey (clinic based) |

Target population: Female clients of family planning clinics and providers of family planning services Recruitment: Women attending general family planning clinics in an urban area of Scotland, and surrounding areas. Providers were recruited among those attending a 1-day family planning update seminar Sample: 687 of 1,000 women participated; 88 of 98 providers participated Characteristics: Female clients: Age: <20 years (8%); 21–40 years (50%); >41 years (42%) Previous pregnancy: 44% Providers: Female: 89% Qualified: <10 years (19%); 11–25 years (64%); >26 years (18%) Specialty: general practice (58%); family planning (19%); both (13%) |

Not described. |

| Gilliam and Hernandez (2007)18 Funding source: No information was provided |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) |

Target population: Providers of reproductive health services to low-income African American adolescents Recruitment: All health care providers (physicians, nurses, medical assistants, social workers) and office staff at two community health centers who self-described as working with African American teens Sample: Four focus group discussions, composed of 27 individuals Characteristics: Health care providers (n=18) Age: 23–60 years, mean 44 years Race/ethnicity: black (56%); white (7%); Hispanic (11%); Asian (26%) Number of adolescents seen per week: <5 (4%); 5–10 (15%); 10–20 (19%); 20–30 (19%); >30 (44%) |

A focus group guide was used, sessions were audio-taped and transcribed, coding was based on research questions with modifications as new themes emerged. |

| Harvey, Beckman, Murray (1989)23 Funding source: Center for Population Research, National Institutes of Health |

Survey (telephone) |

Target population: Sexually active fecund women aged 15 to 44, who reported they had seen/talked to a provider about birth control in the last 3 years Recruitment: Women were randomly selected from a national listing of women who sent in to the manufacturer of the contraceptive sponge for a rebate on their purchase of sponges Sample: 1,057 women (67% of eligible) Characteristics: Age: mean = 29.1 years Race/ethnicity: white (93%); black (5.5%); Hispanic (1.5%) Education: graduated from college (43%) Employed outside the household: 72% Marital status: currently married (61.6%); never married (25.7%); widowed; separated or divorced (12.7%) |

A 35-minute telephone interview was conducted by trained interviewers. |

| Khan and Kirkman (2000)17 Funding source: No information was provided |

Survey (clinic based) |

Target population: Women having an internal (vaginal) examination conducted by a female doctor or nurse Recruitment: Female clients attending five community-based family planning clinics Sample: n=132 questionnaires returned, but 126 had the main questions completed Characteristics: Age: ≤20 years (20%); 21–40 years (73%); >40 years (7%) Race/ethnicity: white British (n=66); Asian (n=24); Afro-Caribbean (n=18); Irish (n=6); other (n=12) |

The questionnaire was completed over a 3-week period in five family planning clinics. It was completed by the clients prior to consultation and examination. |

| Landry, Wei, Frost (2008)19 Funding source: NICHD, National Institutes of Health |

Survey (mail, Internet, fax) |

Target population: Private and public providers of contraceptive care Recruitment: A four-page questionnaire was mailed to a nationally representative samples of private physicians (with ACOG and AAFP membership) and public clinics (health departments, Planned Parenthood clinics, community/migrant health centers, hospitals, other clinics). A second mailing and up to four telephone calls were made Sample: Eligible private providers=1,085, final sample=928 Eligible public provider=1,208 clinics, final sample=49%–73% response rate Characteristics: No other details were provided |

The person who performs most, or a large portion of the contraceptive counseling and education was instructed to complete the survey. |

| Severy and McKillip (1990)24 Funding source: U.S. Office of Population Affairs |

Survey (clinic-based) |

Target population: Women seeking family planning services Recruitment: All low-income female clients of 30 family planning clinics in north central Florida were invited to participate, on randomly selected days. $5 incentive to participate. Sample: n=665 Characteristics: Poverty: ≤100% FPL (80%); 101%–150% FPL (20%) Race/ethnicity: black (41%) |

Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire, which took 15–20 minutes. |

| Silverman et al. (1987)25 Funding source: The James Irvine Foundation, The Joyce Foundation, The Florence and John Schumann Foundation |

Survey: by telephone to women at risk of unintended pregnancy; by mail to providers of family planning services |

Target population: Low-income women aged 18 to 35 years at risk of unintended pregnancy Recruitment: Eligible women in four locations (economically depressed city in the northeast, one section of a large city in the midwest, and two cities on the west coast with substantial Hispanic populations). The mail survey of providers was sent to all family planning clinics and private obstetrician/gynecologist in each of the four communities. Sample: n=760 women (73% response rate). N=353 providers (60% response rate for clinics, <25% response rate for private physicians) Characteristics: Women: the interviews were “almost evenly divided between white, black and Hispanic women” |

No information was provided. |

| Sonenstein, Ku, Schulte (1995)26 Funding source: The Kaiser Family Foundation |

Survey (by telephone) |

Target population: Women aged 21 to 40 Recruitment: The data was collected in 1993 as a follow-up to the 1991 National Survey of Women. The follow-up rate of those interviewed in 1991 was 65%. Sample: n=1,093 |

No information was provided. |

| Sugerman et al. (2000)27 Funding source: RWJ Foundation, MCHB/HRSA |

Survey (clinic-based) |

Target population: Female patients aged 12 to 49 at an urban family planning clinic Recruitment: Purposive sample of family planning clients, stratified by age; excluded clients presenting for prenatal care or abortions Sample: eligible=861; refused=63; enrolled=798; included in sample=780 Characteristics: Age: 13–19 years (n=356); 20–49 years (n=424) Ethnicity (n=757): white, not Latina, 52.3%; white, Latina, 25.3%; African-American,6.3%; Asian/Pacific Islander, 5.5%; other, 10.6% Married: 9.5% Full-time student: 37.5% Employed full-time: 26.9% |

Self-administered anonymous questionnaire that took approximately 20–30 minutes to complete. Subjects completed the questionnaires while waiting to be seen by clinic providers; $5 compensation. Spanish versions were available and used by 4% of participants. |

AAFP, American Academy of Family Physicians; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AFDC, Aid to Families With Dependent Children; EC, emergency contraception; FPL, Federal Poverty Level; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; MCHB, Maternal and Child Health Bureau; NICHD, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; RWJ, Robert Wood Johnson.

Studies identified several characteristics that were considered by family planning clients and providers to constitute quality family planning services. These characteristics were organized based on the six IOM dimensions of quality health care and are summarized in Table 4 and presented in more detail below.

Table 4.

Client and Provider Perspectives of Quality Family Planning Services

| Study | Accessible | Client-Centered | Effective | Efficient | Equitable | Safe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker, Klassen, et al. (2009)12 | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Becker and Tsui (2008)13 | C | C | ||||

| Becker, Stuifbergen, et al. (1997)14 | C | C | ||||

| Bender (1999)15 | C | C | C | |||

| Chambers et al. (2002)20 | C, P | C, P | ||||

| Chetkovich et al. (1999)22 | C | C | C | C | C | |

| Dixon-Woods et al. (2001)16 | C | C | ||||

| Fiddes et al. (2003)21 | C, P | |||||

| Gilliam and Hernandez (2007)18 | P | P | ||||

| Harvey (1989)23 | C | C | C | |||

| Khan and Kirkman (2000)17 | C | |||||

| Landry et al. (2008)19 | P | P | P | P | ||

| Severy (1990)24 | C | C | C | C | ||

| Silverman (1987)25 | C | C | ||||

| Sonenstein (1995)26 | C | |||||

| Sugerman et al. (2000)27 | C | C | ||||

| TOTAL | C=10 P=3 |

C=13 P=4 |

C=4 | C=3 P=1 |

C=4 P=1 |

C=2 |

C, client; P, provider.

Accessibility

Most studies identified clinic accessibility as an important aspect of quality family planning services from both the client and provider perspective.12,14-16,18-20,22-25,27 These included aspects such as convenient clinic hours and locations, walk-in service, free/low-cost services, and providers being reachable by phone.

For example, Landry et al.19 surveyed a nationally representative sample of physicians responsible for providing contraceptive care regarding practices for increasing access to care. The most commonly noted practice for increasing access involved providing telephone counseling to women, with >92% of providers reporting offering this service. Another important strategy involved offering evening or weekend hours, with 27% of obstetricians/gynecologists and up to 90% of Planned Parenthood providers noting this practice. Women interviewed by Becker and colleagues12 reported positive feedback about providers whose locations and hours were convenient and reported favorable feedback on clinics with walk-in service availability, free/low-cost family planning, ease of appointment scheduling, and providers who were reachable by phone. The importance of convenient locations and hours, ability to get an appointment quickly with short waiting times, and providing low-cost services was echoed by several other studies.15,16,20,22,24,25 According to Becker et al.,14 accessibility issues become even more pronounced for family planning clients with disabilities. Women in this study identified physically inaccessible tables and stirrups and inappropriate examining instruments as barriers to good reproductive health care.

In addition to general access to family planning services, ease of contraceptive access and contraceptive choice were frequently cited by clients and providers as important aspects of quality family planning services.12,15,18,19,22,23 Several studies18,22 noted the importance of providing free male condoms in increasing contraceptive access. Women disliked difficulties in obtaining contraception such as having to come back for several visits to get a method12 or having to ask for male condoms.18 Women also disliked being given an insufficient supply of their contraceptive method,12 having to return frequently for refills,12 or not being offered alternative methods of contraception.23 Landry and colleagues19 found wide-ranging beliefs among providers regarding whether expansion of contraceptive coverage to the uninsured is “very important” (obstetrician-gynecologists, 62%; family physicians, 63%; health department staff, 49%; and Planned Parenthood staff, 75%). Additionally, a greater proportion of Planned Parenthood and other public providers (48%–55%) thought that developing new and better contraceptive methods was “very important” compared with obstetrician–gynecologists (38%) and family physicians (33%).19

Client-Centered

Client-centered factors were the most common aspects of quality identified in this review. Most of these factors centered on stigma and embarrassment, confidentiality, tailoring services to meet specific needs, autonomy and confidence, the client–provider relationship, and comfort of the facilities.

The management of client comfort and ease during a clinic visit was one of the most commonly discussed characteristics of quality family planning identified by clients and providers.12-14,16,17,20,21 Women are often embarrassed during the family planning visit because it usually involves an intimate physical examination and discussion of sensitive topics, such as sexual history and behavior. Minorities, non-English speakers, and younger women may experience greater embarrassment, because of their unique profiles. Women interviewed in the Dixon-Woods et al. study16 felt it was important that the clinic staff alleviate their feelings of stigma and embarrassment, appear non-judgmental, and be able to deal with potentially embarrassing circumstances (e.g., sexually transmitted infections). Both health professionals and young people advocated for peer education for teenage family planning clients and suggested that providers be taught to be more sensitive and less judgmental in relating with teenage family planning clients.20

Several strategies have been examined for reducing stigma and embarrassment associated with family planning visits, including changing the sex of the healthcare provider and using chaperones during the examination. Overall, studies found that women prefer to have a female clinician conduct their examinations, particularly vaginal/pelvic examinations. Differences in this preference were found by ethnicity. Becker and Tsui13 found that both English- and Spanish-speaking Latinas were more likely than white, non-Latina clients to report a preference for a female clinician. This study also found that clinic quality ratings were reduced for clients not seen by a clinician of their preferred gender. Fiddes and colleagues21 found that 20% of female family planning clients would only accept a female doctor, 56% would prefer a female doctor, 1% would prefer a male doctor, and 24% had no preference.

The presence of a chaperone during physical examinations (as part of a family planning visit) could either alleviate or intensify clients’ feelings of embarrassment. Fiddes et al.21 examined attitudes toward chaperones during pelvic examinations among both women and providers. Approximately two thirds of women reported they would not be embarrassed by the presence of a chaperone, whereas one third indicated they would be or might be embarrassed. Khan and Kirkman17 found that the preference of having a chaperone present is likely related to the sex of the provider, with 85% of women preferring not to have a chaperone present when having an internal examination done by a female provider. In general, providers seem less likely to prefer a chaperone during pelvic examinations, with one study21 reporting that only 10% of providers reported routinely using a chaperone. This preference is also likely related to the sex of the provider, with male providers comprising 78% of those who reported routine use of a chaperone.21

Women with physical or mental disabilities may experience considerably greater obstacles in using family planning services, often leading to increased stigma and embarrassment. Physical impairments (such as paralysis or cerebral palsy) may limit contraceptive options; for example, limited arm mobility may interfere with the use of oral contraceptives or diaphragms, and decreased pelvic sensation may mask potential problems with an intrauterine device.14 Women with disabilities also face barriers to care caused by the misunderstandings or unsupportive attitudes of providers. The women interviewed by Becker and colleagues14 sensed providers’ discomfort and nervousness about providing them family planning services.

The security of health information is a long-held tenet of medical care, which is also seen in the perspectives of family planning service clients.12,14,15,20,27 Becker et al.14 found that confidentiality of services was important to women, both while being seen by a provider and while in the waiting room. In one study,12 participants expressed appreciation for a clinic procedure in which clients received cards that described the purpose of their visit so they did not have to say it out loud while they were waiting.

Confidentiality was a particularly important issue for adolescents in these studies. Forty-nine percent of adolescents interviewed in the Bender study15 reported not wanting to risk meeting one’s parents (or anyone who knew their parents) while receiving services at a family planning clinic. Several of the teenagers interviewed by Chambers and colleagues20 were concerned with increasing privacy and highlighted strategies, such as the distribution of health messages in restrooms, youth clubs, teen magazines, and the Internet, as possible ways of communicating family planning information while still maintaining privacy, in addition to communicating such messages in a more direct manner (such as face to face).

Tailoring of services to the specific needs of populations, particularly adolescents, was an important characteristic in several studies.15,18,20,22 In the Chambers et al. study,20 young people emphasized the importance of family planning services being youth-centered, as a way to reduce the frequency of teenage pregnancy. Young people also suggested more creative ways of communicating sexual health and education messages than did professionals, referring to color and cartoons and information disseminated through TV, the Internet, magazines, posters, leaflets, and peers.20 Chetkovich and colleagues22 found similar results among both adults and teens regarding the need for health education materials to be relevant. Most adolescents (92%) in the Bender study15 wanted access to sexual and reproductive health services that were specialized for young people. Services most desired included information about contraceptive methods (86%), and 47% opposed a mandatory physical examination at their first visit.15 Gilliam and Hernandez18 reported that physicians identified establishing frequent, closely spaced appointments as an effective strategy for working with teens, particularly when teen clients chose short-acting contraceptive methods.

Becker and Tsui13 reported that blacks and English-speaking Latinas were significantly more likely than white, non-Latinas to prefer receiving services at general health centers, rather than at sites specifically tailored to family planning (OR=1.6 and OR=1.5, respectively). Study authors posit that this difference may reflect that minorities are more likely to have poorer health than whites, and thereby need the convenience of addressing multiple health needs at a single location.13

Another characteristic of quality family planning services reported by patients in the literature was the empowerment of clients in their own health management.12-14,16,21 Women in the Dixon-Woods et al. study16 emphasized their need to be kept well informed, with clear explanations from staff, particularly regarding medical procedures, treatments, and prognosis. Women wanted to feel free to ask questions of staff and were keen to have written information available. According to Becker and Tsui,13 black women had higher odds than whites of reporting ever having been pressured by a healthcare clinician to use a contraceptive method.

In a study by Becker and colleagues,12 women reported being happy with family planning care that they considered informational and educational. They appreciated being informed about various contraceptive methods, knowing the purpose of tests and the meaning of test results, and they desired providers and staff to keep them informed about procedural aspects such as expected wait times and the meaning of forms they were asked to sign. Similarly, women in this study disliked their care when they felt pressured to make decisions, when they felt their providers did not respect their autonomy, or when they were not provided with enough information.

In another study by Becker et al.,14 female family planning clients with disabilities reported feeling ignored and patronized, and were not given adequate explanations of their condition or of upcoming procedures. Some interviewees mentioned that providers did not discuss pregnancy prevention issues with them.14 Women gave positive ratings to providers with positive attitudes, who asked questions, were willing to learn, and respected client autonomy.14

Factors identified as important to the client–provider relationship included increased time with client, communication and relationship, and providing continuity in care. In several studies, clients considered family planning services that invested more time with them as higher quality.15,18,22,23 For example, 97% of the adolescents interviewed in the Bender study15 reported wanting more time for discussion with their healthcare providers. Providers also indicated that increased time with their clients was an important element of providing quality family planning services.18 Gilliam and Hernandez18 found that providers working with teens at family planning clinics placed a priority on spending time and conversing informally with patients. Another study found that 48%–49% of private providers considered changing reimbursement (e.g., billing codes) to allow for more counseling time as “very important.”19

The quality of patient–provider communication and relationship is naturally interwoven into the other aforementioned characteristics of family planning services; however, it is itself a distinct feature identified by clients and providers as important for the quality of family planning services.12,15,22-25 Women interviewed by Becker and colleagues12 reported being pleased with providers who were friendly, conveyed warmth and interest, made small talk, asked questions, and communicated with them during exams. Women also preferred providers who made it easy to talk about sexuality and contraception and did not scold, judge, or lecture them. Additionally, women considered providers as uncaring when they were rough in performing exams, when they seemed to be there “just for a job,” and when they ignored clients or seemed impatient in answering questions.12 According to Gilliam and Hernandez,18 communication tactics used by teen family planning clinics included acceptance of teen language and customs, speaking to teens in their own language, and awareness of body language.

Although a less commonly cited aspect of quality family planning identified by patients and providers, some studies reported the desire of clients to keep the same providers throughout their care.12,22 For example, women interviewed by Becker et al.12 preferred to see the same provider across visits, and disliked it when they were unable to do this. Both Spanish- and English-speaking Latinas were more likely than white, non-Latinas to consider clinician continuity at family planning visits important.13

The appearance, arrangement, and decor of family planning clinics can communicate non-verbal messages that foster or detract from client comfort and confidence. Becker and colleagues12 found that women reported feeling comfortable if the health facility was warm, welcoming, and clean. One woman in this study, who received care through the obstetrics and gynecology department of her HMO, felt uncomfortable because the environment was highly focused on mothers. Eighty-eight percent of the adolescents interviewed in the Bender study15 reported wanting a more comfortable environment, and 44%–54% of respondents suggested having youth-appropriate educational material on display at family planning clinics.

Effective

A few studies noted effectiveness in care as an important aspect of family planning quality. Four studies12,22-24 that discussed this aspect were from the client’s perspective and focused primarily on the competency and training of their providers. For example, in the study by Harvey et al.,23 one of the most frequently reported reasons for being satisfied with the healthcare provider relationship was feeling that their provider was knowledgeable and competent. Becker and colleagues12 also noted the importance of technical quality of care through their interviews, which found that their feelings during examinations, whether their problem was solved, and whether their follow-ups or referrals matched expectations, were particularly important to some women’s perceptions of quality care.

Efficient

Four studies12,19,22,26 reported factors related to efficiency of services as important aspects of family planning service quality. These focused on factors such as shorter wait times, appointment reminders, offering test results by phone, and combining reproductive and general health services. In the Becker et al. study,12 women appreciated several organizational features, including short waiting times, appointment reminders, quick test results by phone, and being told whom to contact if they had questions or concerns following their appointments. Similarly, women disliked long waits, receiving conflicting information from different staff members, logistic problems that interfered with their care (e.g., appointments were not written down), and questions or tests that were unnecessarily repeated during visits.12 Sonenstein and colleagues26 noted that the majority of women in their study would prefer to receive care in a place where they can also receive general health care, with a similar finding reported by Chetkovich et al.22

Equitable

Several articles discussed the importance of providing equitable services, particularly as related to factors such as language, disability, and age.12-15,19,24 Becker and colleagues12 found that it was particularly important to Spanish-speaking Latinas that the care and information they received was language appropriate. Similar needs for bilingual staff and the need to be able to treat individuals from different backgrounds were noted in other studies.19,24 Another article14 noted many disparities in care among women with disabilities, including inaccessible equipment and facilities, limited contraceptive options, and lack of knowledge about disabilities on the part of providers. Finally, Bender15 acknowledged the importance of equal access to services as highly valued among adolescents.

Safe

Two studies12,22 reported safety as an important aspect of quality family planning services, both of which focused on the safety of contraception from the client’s perspective. Becker et al.12 noted that women often mentioned screening for contraindications to contraception as an important aspect of quality. Similarly, Chetkovich and colleagues22 found that some women they interviewed felt their providers did not take their concerns about side effects seriously.

Additional Studies

To further support the findings presented here, a targeted search was conducted in PubMed for the periods March 2011 through January 2015 to identify research that may have been published since this review was completed. One additional study was identified, in which Pilgrim and colleagues30 examined women’s (N=748) perceptions of service quality and satisfaction during their first visit at a Title X family planning clinic. They identified client-centeredness (e.g., clinicians were respectful, listened, and provided thoughtful explanations) as a significant factor in determining a client’s perceptions of service quality and satisfaction. Other important factors included experiences with the facility environment such as waiting room times and interactions with staff.

Conclusions

This systematic review of the literature sought to update the synthesis of findings from research examining the quality of family planning services and the impact of improved service quality on reproductive health outcomes. Findings from this systematic review were presented to an expert technical panel in May 2011 at a meeting convened by the OPA and CDC. Along with feedback from other experts, the information was used to develop recommendations included in the 2014 “Providing Quality Family Planning Services.”10

No new intervention studies were identified, confirming that there is very little recent research examining whether efforts to improve the quality of family planning services lead to improved short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes. However, several new studies describing client and provider perspectives on what constituted “quality” care were identified. This paper extends earlier research by considering these new studies within the framework of quality care that was defined by IOM, and had six dimensions of quality care—accessible, client-centered, effective, efficient, equitable, and safe.3

Key findings from the descriptive research studies were that clients and providers were most likely to identify issues around accessibility, client-centeredness, and, to a lesser extent, equitability when discussing the quality of family planning services. Important themes were that clients’ autonomy in decision making should be respected, clients should be offered a wide range of contraceptive options, efforts should be taken to reduce stigma and embarrassment, family planning services should be confidential, and a positive interactive style between client and provider was valued. Findings also demonstrate differences in the experience of family planning services based on factors such as race, age, and disability. This suggests that tailoring services to address specific characteristics and needs of clients is an important component of providing quality family planning services.

Although mentioned less frequently, clients and providers also noted the importance of the following dimensions of care: effectiveness, efficiency, and safety. Important themes were that providers should be knowledgeable and competent, services should be well organized and administered, and providers should be respectful and attentive to women’s concerns about contraceptive method side effects. The fact that there were relatively fewer mentions of effectiveness, efficiency, and safety of care may be due to the fact that assessments of safety and effectiveness requires clinical skills and training that many clients do not have and that providers assume is a given. In addition, most studies either asked participants broad, open-ended questions or more-targeted questions on aspects of family planning quality not directly related to effectiveness, efficiency, and safety. To more fully understand these client and provider perceptions in family planning services, additional research is needed focused specifically on these aspects.

Other avenues for future research involve further examination of disconnects between what clients and providers identify as aspects of quality in family planning services. Although this systematic review examined both client and provider perspectives, relatively few studies (k=4) were identified that focused on providers, and of these, only two articles20,21 directly compared the perspectives of providers with those of clients. Both studies found differences between clients and providers, particularly in the types of services that should be provided to enhance client-centered care.

Finally, additional research is needed examining the connection between perceptions and actual behavior. Often, individuals may state that they believe something is important, particularly when it deals with access to healthcare services; however, when those additional services are provided, they may go underutilized. Future studies should be conducted to explore strategies for increasing utilization of services and improvements in health outcomes based on the perceptions of family planning quality identified in this review.

In sum, this review of the existing literature on quality in the delivery of family planning services highlights the need to develop performance measures that reflect the expressed preferences of clients and providers and are consistent with IOM’s dimensions of quality care, to use the performance measures in the care setting so that care can be improved, and to conduct intervention research and evaluation so that the impact of quality improvement practices on short-, medium-, and long-term health outcomes can be confirmed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was received from CDC under contract number 2009-N-11195.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC or the Office of Population Affairs.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Appendix

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.017.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the united states: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485. 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, Henshaw SK. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60(7):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Your Guide to Choosing Quality Health Care. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.USDHHS. Consensus Statment on Quality in the Public Health System. 2008. www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/quality/quality/phqf-consensus-statement.html.

- 6.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259. 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flodgren G, Pomey MP, Taber SA, Eccles MP. Effectiveness of external inspection of compliance with standards in improving healthcare organisation behaviour, healthcare professional behaviour or patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD008992. 10.1002/14651858.CD008992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker D, Koenig MA, Kim YM, Cardona K, Sonenstein FL. The quality of family planning services in the United States: findings from a literature review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39(4):206–215. 10.1363/3920607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR–04):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tregear SJ, Gavin LE, Williams JR. Systematic review evidence methodology: providing quality family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S23–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker D, Klassen AC, Koenig MA, et al. Women's perspectives on family planning service quality: an exploration of differences by race, ethnicity and language. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41(3):158–165. 10.1363/4115809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker D, Tsui AO. Reproductive health service preferences and perceptions of quality among low-income women: racial, ethnic and language group differences. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(4): 202–211. 10.1363/4020208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker H, Stuifbergen A, Tinkle M. Reproductive health care experiences of women with physical disabilities: a qualitative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78(12):S26–S33. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bender SS. Attitudes of icelandic young people toward sexual and reproductive health services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31(6):294–301. 10.2307/2991540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon-Woods M, Stokes T, Young B, et al. Choosing and using services for sexual health: a qualitative study of women's views. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77(5):335–339. 10.1136/sti.77.5.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan NS, Kirkman R. Intimate examinations: use of chaperones in community-based family planning clinics. BJOG. 2000;107(1):130–132. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilliam ML, Hernandez M. Providing contraceptive care to low-income, African American teens: the experience of urban community health centers. J Community Health. 2007;32(4):231–244. 10.1007/s10900-007-9045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landry DJ, Wei J, Frost JJ. Public and private providers' involvement in improving their patients' contraceptive use. Contraception. 2008;78(1):42–51. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers R, Boath E, Chambers S. Young people's and professionals' views about ways to reduce teenage pregnancy rates: to agree or not agree. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28(2):85–90. 10.1783/147118902101196009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiddes P, Scott A, Fletcher J, Glasier A. Attitudes towards pelvic examination and chaperones: a questionnaire survey of patients and providers. Contraception. 2003;67(4):313–317. 10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chetkovich C, Mauldon J, Brindis C, Guendelman S. Informed policy making for the prevention of unwanted pregnancy. Understanding low-income women's experiences with family planning. Eval Rev. 1999;23(5):527–552. 10.1177/0193841X9902300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey SM, Beckman LJ, Murray J. Health care provider and contraceptive care setting: the relationship to contraceptive behavior. Contraception. 1989;40(6):715–729. 10.1016/0010-7824(89)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Severy LJ, McKillop K. Low-income women's perceptions of family planning service alternatives. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(4):150–157, 168. 10.2307/2135605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverman J, Torres A, Forrest JD. Barriers to contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1987;19(3):94–97, 101–102. 10.2307/2135174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonenstein FL, Ku L, Schulte MM. Reproductive health care delivery. Patterns in a changing market. West J Med. 1995;163(3 suppl):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugerman S, Halfon N, Fink A, et al. Family planning clinic patients: their usual health care providers, insurance status, and implications for managed care. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(1):25–33. 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amey AL. Medicaid Managed Care and Family Planning Services: An Analysis of Recipient Utilization and Choice of Type of Provider. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonenstein FL, Porter L, Livingston G. Missed Opportunities: Family Planning in the District of Columbia. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilgrim NA, Cardona KM, Pinder E, Sonenstein FL. Clients' perceptions of service quality and satisfaction at their initial Title X family planning visit. Health Commun. 2014;29(5):505–515. 10.1080/10410236.2013.777328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.