ABSTRACT

Multiple coronaviruses (CoVs) can cause respiratory diseases in humans. While prophylactic vaccines designed to prevent infection are available for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), incomplete vaccine efficacy, vaccine hesitancy, and the threat of other pathogenic CoVs for which vaccines do not exist have highlighted the need for effective antiviral therapies. While antiviral compounds targeting the viral polymerase and protease are already in clinical use, their sensitivity to potential resistance mutations as well as their breadth against the full range of human and preemergent CoVs remain incompletely defined. To begin to fill that gap in knowledge, we report here the development of an improved, noninfectious, cell-based fluorescent assay with high sensitivity and low background that reports on the activity of viral proteases, which are key drug targets. We demonstrate that the assay is compatible with not only the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein but also orthologues from a range of human and nonhuman CoVs as well as clinically reported SARS-CoV-2 drug-resistant Mpro variants. We then use this assay to define the breadth of activity of two clinically used protease inhibitors, nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir. Continued use of this assay will help define the strengths and limitations of current therapies and may also facilitate the development of next-generation protease inhibitors that are broadly active against both currently circulating and preemergent CoVs.

IMPORTANCE

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are important human pathogens with the ability to cause global pandemics. Working in concert with vaccines, antivirals specifically limit viral disease in people who are actively infected. Antiviral compounds that target CoV proteases are already in clinical use; their efficacy against variant proteases and preemergent zoonotic CoVs, however, remains incompletely defined. Here, we report an improved, noninfectious, and highly sensitive fluorescent method of defining the sensitivity of CoV proteases to small molecule inhibitors. We use this approach to assay the activity of current antiviral therapies against clinically reported SARS-CoV-2 protease mutants and a panel of highly diverse CoV proteases. Additionally, we show this system is adaptable to other structurally nonrelated viral proteases. In the future, this assay can be used to not only better define the strengths and limitations of current therapies but also help develop new, broadly acting inhibitors that more broadly target viral families.

KEYWORDS: FlipGFP, coronaviruses, antivirals, Zika virus, Epstein–Barr virus, CoV Mpro, CoV PLpro

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a genetically diverse group of zoonotic respiratory pathogens with pandemic and epidemic potential (1). In 2019, a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged and initiated the global COVID-19 pandemic that has led to over 600,000,000 infections and over 6,000,000 deaths worldwide (2). This marks the third time in the 21st century that a novel coronavirus has made the jump to humans (3, 4). While the deployment of prophylactic vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 is the primary public health measure to control infection rates, there remain susceptible populations due to either incomplete vaccine efficacy or an unwillingness or inability to be vaccinated. Additionally, vaccine- or infection-mediated immunity has already exerted strong selection pressures on the virus, leading to the emergence of strains that are less sensitive to preexisting adaptive immune responses (5 - 7). For these reasons, antiviral compounds that directly target virus replication are essential for limiting viral disease morbidity and mortality.

Antiviral therapeutics are designed to specifically inhibit some aspect of the virus lifecycle within an infected host cell. Currently, there are three antivirals approved under an emergency use authorization for the treatment of COVID-19 in the United States by the FDA: molnupiravir, remdesivir, and nirmatrelvir (marketed in combination with ritonavir as PAXLOVID). Molnupiravir and remdesivir are both RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors with clinical efficacy rates of 31% and 87% in lowering rates of hospitalization or death, and the most recently approved antiviral, nirmatrelvir, targets the 3CL protease (Mpro, also known as Nsp5, and 3CLpro) and has a clinical efficacy rate of 89% (8 - 10).

CoVs encode their own error-prone RdRp, naturally leading to high viral diversity, which provides a substrate for the emergence of resistance (11). Mutations associated with resistance have already been studied for both molnupiravir and remdesivir, and there are increasing studies beginning to investigate nirmatrelvir-driven mutations in vitro (12 - 23). However, due to their rapid emergence and limitations on the generation of replication-competent, drug-resistant viruses in laboratory research, our understanding of the effects of mutations that are selected for after drug treatment remains limited. In addition to an incomplete understanding of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro variant interactions with therapeutic inhibitors, we have even less knowledge of the potential sensitivity of preemergent coronaviruses in zoonotic reservoirs to our current inhibitors. While testing against epidemic and endemic non-SARS-CoV-2 human CoVs is standard, biosafety concerns and limitations on the technical ability to culture viruses from zoonotic reservoirs have limited these types of studies for other diverse CoVs.

One way to avoid the constraints that limit our ability to address both information needs described above is through the design of cell-based, noninfectious reporter assays. Indeed, a number of such assays have previously been reported, including by our group (24 - 39). The general design of these assays is the introduction of a viral gene into cells followed by monitoring a phenotypic readout, which allows one to safely evaluate drug-resistant mutations and assay viral protein activities from viruses that are difficult to isolate and/or culture. Fluorescent/bioluminescent reporter assays have been developed to identify inhibitors of discrete steps of the virus lifecycle such as attachment and membrane fusion (27, 31), RdRp activity (25, 37 - 39), and Mpro activity (24, 29, 30, 32 - 36). Of the reporter systems focused on Mpro activity, the utility of these assays is affected by background signal, which limits the overall dynamic range of the assay (24). Additionally, these assays have for the most part been used with only one (or at most a few) viral proteases, and thus, it has remained unclear if these types of assays, especially those that require cleavage of a single protease motif, would be broadly adaptable to proteases from highly diverse coronaviruses. Our goal therefore became to develop a fluorescent protease reporter assay with reduced background signal that would also be adaptable to a broad range of viral proteases.

Here, we detail the generation of a novel fluorescent reporter assay that accomplishes these goals. Expanding on our previous work (24), we engineered a variant FlipGFP (40) protein to contain a protein degradation domain (and an additional viral protease cleavage site) on one of the subunits to shorten its half-life. In the presence of a viral protease, not only is the GFP signal activated but the half-life of the protein is extended. We show that this improved assay has minimal background but not at the expense of reporter signal, leading to more than 100× greater dynamic range compared to earlier designs. We also show that this reporter design can be adapted to report on structurally diverse viral proteases such as the SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro), the Zika virus (ZIKV) protease NS2B-NS3, and the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) protease. Finally, we use this system to assess the drug sensitivity of clinically reported SARS-CoV-2 Mpro variants and identify the differential inhibitory activities of nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir against diverse, preemergent CoV proteases. In the future, this improved reporter assay can be used to not only test novel antivirals for their activities against diverse CoV proteases but may also serve as a tool for antiviral compound screening and optimization.

RESULTS

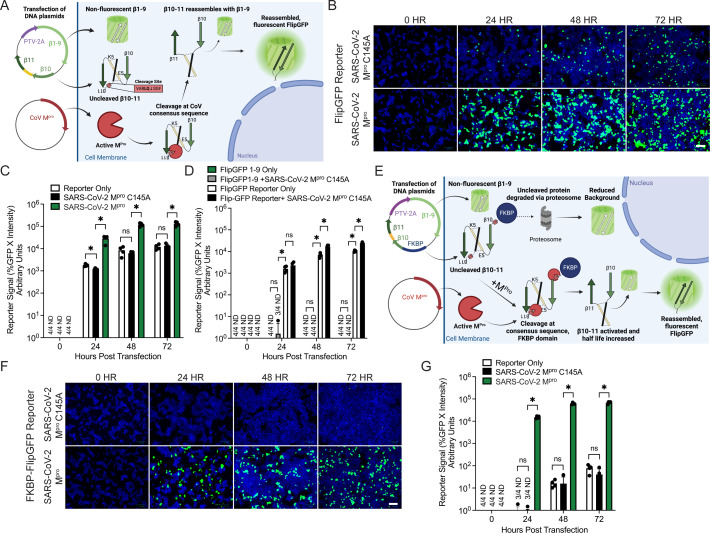

Previously, we reported the development of a “first-generation” cellular fluorescent reporter assay to assess SARS-CoV-2 Mpro activity (24). This system consisted of an expression plasmid encoding the FlipGFP protein co-transfected with a plasmid expressing the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protease into human HEK293T cells. The reporter plasmid made use of a 2A peptide to express part of the GFP protein (strands β1–9) separately from the rest (strands β10–11). β10–11, however, were expressed and held in an inactive conformation by virtue of a linker sequence that also contains a viral protease site. Upon viral protease-mediated linker cleavage, β10–11 of GFP reorient themselves, reassemble with the β1–9 strands, and a fluorescent signal is generated (Fig. 1A). While this reporter construct showed robust signal in the presence of the WT Mpro, parallel transfections of a C145A catalytically dead mutant showed noticeable background fluorescent signal, limiting the dynamic range of the assay (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig 1.

Generation and validation of a FKBP-FlipGFP reporter assay to report on CoV Mpro activity. (A) Diagram of the initial FlipGFP CoV reporter system with CoV-specific cleavage site: VARLQ↓SGF (24). (B) Images of 293T cells with visible fluorescence at 0, 24, 48, or 72 h post-transfection of the FlipGFP reporter with either a catalytically dead SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A mutant (top) or WT SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (bottom). Green, cleaved FlipGFP; blue, nuclei; scale bar = 100 µm. (C) Quantification of reporter signal in 293Ts from panel B. Reporter signal was calculated as the percentage of cells that were GFP+ multiplied by the average intensity of fluorescent signal. ND, value not detected. (D) Quantification of reporter signal in 293Ts either 0, 24, 48, or 72 h post-transfection of the FlipGFP reporter (containing β1–11) either alone or with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A, or a plasmid expressing FlipGFP β1–9 either alone or with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A. (E) Diagram of the FKBP-FlipGFP reporter assay. (F) Images of 293T cells 0, 24, 48, or 72 h post-transfection with the FKBP-FlipGFP reporter and either a catalytically dead SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A mutant (top) or WT SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (bottom). (G) Quantification of reporter signal in 293Ts from panel F. For all panels, data are shown as means with SDs from independent biological replicates of 4. P values were calculated using multiple Mann–Whitney U tests (*, P < 0.05; ns, not significant).

To identify the source of background fluorescence in our FlipGFP reporter, we transfected a plasmid expressing FlipGFP β1–9, or a plasmid expressing our full reporter, either alone or with the catalytically dead SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A mutant. At all timepoints (24–72 h) post-transfection we observed significant background fluorescent signal only in the cells transfected with the full reporter (Fig. 1D). The signal was undetectable at all timepoints in cells transfected with a plasmid-expressing FlipGFP β1–9 alone or with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A, indicating that either undesired partial cleavage or GFP activation by uncleaved FlipGFP β10–11, was occurring. To address and minimize this background fluorescence, we decided to incorporate a protein destabilization domain into the FlipGFP β10–11 component of our reporter.

Previously, it has been reported that fusing a L106P mutant of the human FKBP12 protein is a viable method for targeting the fusion protein for proteosome-mediated degradation (41 - 44). We reasoned that by “tagging” β10–11 with FKBP but separating them with an additional CoV cleavage site, viral protease cleavage could activate and stabilize GFP signal at the same time (Fig. 1E). To test our hypothesis, we transfected an FKBP-FlipGFP reporter into cells either alone, with the WT SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, or with the C145A mutant. As anticipated, at all timepoints, we observed significantly reduced background signal (Fig. 1F and G). Importantly, this reduced background did not come at a significant expense of reporter signal. While we didn’t formally measure differences in half-life of the cleaved vs. noncleaved FKBP-FlipGFP reporter, compared to the first generation of this assay, we observed a more than 100× increase in signal dynamic range with the improved FKBP-FlipGFP assay.

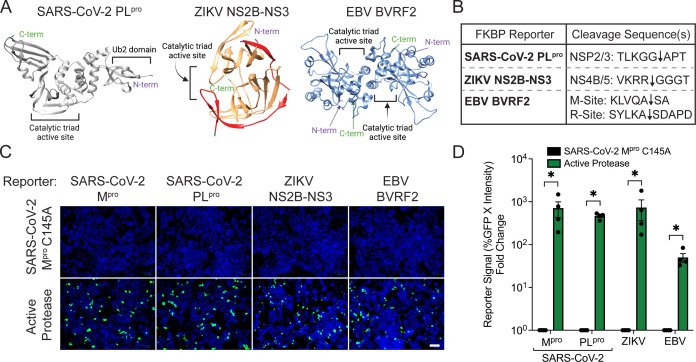

Viral proteases are utilized by a variety of viral families to aid in replication, making them highly attractive therapeutic targets (45 - 47). We therefore wanted to investigate next if our improved reporter system could be adapted to unrelated viral proteases. We first selected another SARS-CoV-2 viral protease, the papain-like protease, PLpro. PLpro is a cysteine protease consisting of a N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain separated from a catalytic core domain (Fig. 2A, left) (33, 46, 48). PLpro is not only responsible for cleaving the viral polyprotein to create the Nsp1, Nsp2, and Nsp3 proteins, but it also has noted deubiquitinating and deISG15ylating properties, making it a unique innate immune antagonist (33, 46, 49). We also selected the NS2B-NS3 proteins from the flavivirus, Zika. NS2B-NS3 is a chymotrypsin-like serine protease and cofactor complex consisting of a histidine-aspartic acid-serine catalytic domain (Fig. 2A, middle) (50 - 53). The ZIKV NS2B-NS3 is essential for viral replication, as it is responsible for all cleavages of the viral polyprotein to yield 10 viral proteins (51). Finally, we selected BVRF2 from the gammaherpesvirus, EBV, which is a serine homodimer protease consisting of a serine-histidine-histidine catalytic triad (Fig. 2A, right) (54). BVRF2 is essential for maturation of the viral capsid and generation of fully infectious virions and is conserved across other herpesviruses (54, 55). We reasoned that testing our reporter assay with these divergent proteases would not only represent a robust test of the system but also directly generate assays for other attractive viral drug targets.

Fig 2.

Application of FKBP-FlipGFP reporter system to report on diverse viral proteases. (A) Cartoon representation of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (left, gray), ZIKV NS2B-NS3 (middle, NS3 in orange and NS2B in red), and the EBV BVRF2 dimer (right, light blue). The N-terminal and C-terminal ends of each protease are shown in purple or green, respectively. Catalytic active sites are indicated in black. (B) Representation of the viral cleavage site(s) inserted into each respective FKBP-FlipGFP reporter. Black arrows represent where cleavage occurs. (C) Images of 293T cells 32 h post-transfection of the respective reporter of each virus with either the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A mutant or the active protease of each virus. Green, cleaved FKBP-FlipGFP; blue, nuclei; scale bar = 100 µm. (D) Quantification of 293T cells from panel C. For each reporter, the reporter signal fold change relative to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A was calculated. For all panels, data are shown as means with SEMs from independent biological replicates of 4. P values were calculated using multiple Mann–Whitney U tests (*, P < 0.05; ns, not significant).

To test if our FKBP-FlipGFP system could be used to report on the activity of these diverse viral proteases, we engineered reporter systems tailored to each virus using one or two cleavage sequences corresponding to each protease (56 - 58) (Fig. 2B). When co-transfected into cells with either an expression plasmid encoding the appropriate protease or the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145A as a transfection control to assess background signal, we found that all viral reporters showed visible fluorescent signal (Fig. 2C). Quantification of reporter signal showed significant increases in fluorescent signal compared to background for all viral reporters (Fig. 2D). While the ZIKV reporter showed the highest fold-change increase of ~700 compared to the background, SARS-CoV-2 PLpro and EBV both showed strong fold-change increases of ~450 and ~50, respectively. These experiments indicate that the FKBP-FlipGFP system is not only useful as a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro assay but can also report on protease activity across structurally diverse viral proteases.

Before returning to our initial goal of understanding how Mpro variation affected susceptibility to chemical inhibitors, we first needed to confirm that our FKBP-FlipGFP system would appropriately report on inhibition of viral protease activity by known drugs such as nirmatrelvir. We therefore transfected cells with an optimized amount of viral reporter and protease constructs and treated them with a range of concentrations of nirmatrelvir as well as 2 µM CP-100536, a P-glycoprotein efflux inhibitor, to limit cellular drug efflux (13, 59 - 61). While no significant impact on cell viability was observed, fluorescent signal was reduced in a dose-dependent manner with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) in the ~400 nM range (Fig. 3A). This is generally consistent with (but on the higher end of) the reported IC50 of this drug, which varies from the low nM to low μM range depending on cell type and experimental conditions used (13, 15, 62 - 66).

Fig 3.

Activity of drug-resistant Mpro mutations can be investigated using the FKBP-FlipGFP CoV reporter. (A) Normalized quantification of reporter signal in 293T cells 24 h post-transfection with the reporter and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, with 2 µM P-glycoprotein inhibitor, and indicated doses of nirmatrelvir. The average total cell count is shown in black at each concentration of drug. (B) Selected Mpro single- or double-point mutations from positions reported in Pfizer’s fact sheet for healthcare providers from the EPIC-HR clinical trial to be cloned into expression plasmids (67). (C) Cartoon representation of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (gray) in complex with nirmatrelvir (red), with positions of amino acid mutations described in panel B shown in stick form (cyan). The C-terminal and N-terminal ends of each protease are shown in orange or blue, respectively. (D) Images of 293T cells 24 h post-transfection of reporter and indicated SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Green, cleaved FKBP-FlipGFP; blue, nuclei; scale bar = 100 µM. (E) Normalized quantification of reporter signal in 293T cells 24 h post-transfection with the reporter and indicated SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, with 2 µM P-glycoprotein inhibitor, and either DMSO-vehicle or 2.5 µM nirmatrelvir. All samples normalized to DMSO-vehicle. (F) Normalized quantification of reporter signal in 293Ts treated with 2 µM P-glycoprotein inhibitor and varying concentrations of nirmatrelvir and transfected with reporter and the indicated SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (WT, green; W207L, orange; S144A, purple; E166V + L50F, blue). The average total cell count is shown on the right axis at each concentration of drug. For all panels, data are shown as means with SEMs from independent biological replicates of 4. P values were calculated using multiple Mann–Whitney U tests (*, P < 0.05; ns, not significant).

We were next interested in using our assay to understand the effects of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro mutations that arise in patients receiving PAXLOVID. To begin to investigate these mutants, we first cloned a panel of mutant SARS-CoV-2 Mpro genes that were reported in the PAXLOVID EPIC-HR clinical study (Fig. 3B) (67). These mutations are found across the three domains of Mpro, with multiple clustering around the active site of the enzyme in domain II (Fig. 3C). We next co-transfected our SARS-CoV-2 reporter and the individual mutant proteases into cells. By 24 h post-transfection, all mutant Mpro proteins induced at least some fluorescent signal compared to our negative control, with some inducing more fluorescence than others (Fig. 3D). Notably, the L30F, G109E, C145F, and A266P Mpro proteins induced very little fluorescence, likely indicating either reduced protease activity or shortened protein half-life.

To test the drug sensitivity of these mutant Mpro proteins, each mutant Mpro expression plasmid with appreciable signal was co-transfected into cells with the FKBP-FlipGFP reporter and treated with a fixed concentration of nirmatrelvir. While WT SARS-CoV-2 was inhibited to the expected degree, every other mutant Mpro (with the exception of T196A) displayed reduced sensitivity to the drug (Fig. 3E). M82I, D153H, H172Y, A260D, D263E, and V297A all displayed reduced, but still significant inhibition by the drug, while other mutations such as A7S, S144A, E166V + L50F, and W207L remained largely uninhibited. We next decided to perform additional characterization of three of these strongly resistant mutant Mpros: S144A, E166V + L50F, and W207L. While S144A and E166V + L50F have been investigated by other groups, the W207L mutation has been less well characterized (14 - 19 - 22 - 67 - 68). We treated reporter containing cells expressing each of these mutant proteases with varying concentrations of nirmatrelvir. While WT SARS-CoV-2 was again inhibited in the several hundred nM range as expected, the W207L mutation had an IC50 = 4.41 µM, the S144A had an IC50 = 12.42 µM, and the E166V + L50F mutation had an IC50 = 49.14 µM (Fig. 3F). These IC50 trends are consistent with other studies that have reported S144A as ~20 fold and E166V + L50F ~100 fold more resistant to nirmatrelvir than WT (14, 15, 17, 18, 22, 67, 68). These data together suggest that our FKBP-FlipGFP Mpro reporter offers a safe and rapid way to interrogate the drug sensitivity of mutant Mpro proteins.

In addition to drug-resistant mutants, zoonotic CoVs also pose a threat to global health as their emergence (potentially novel recombinants from co-infections) can lead to viral epidemics and pandemics (69 - 73). Because culturing these viruses is frequently difficult, we also wanted to assess the ability of our FKBP-FlipGFP system to report on a wide breadth of diverse Mpro proteins from human and nonhuman CoVs. We therefore selected a panel of CoV Mpro proteases from well-annotated strains representing the four genera of CoVs: beta-, alpha-, gamma-, and deltacoronaviruses (Fig. 4A). Analysis of their Mpro sequences revealed varying sequence homology from the closest relative of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, at ~97% sequence homology, to the lowest sequence homology of Bulbul coronavirus HKU11 and porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) at ~49%. Because our reporter relies on sequence-dependent cleavage of the reporter protein, we performed alignments of the native Nsp4/5 and Nsp5/6 cleavage junctions to understand if it was likely that all these proteases would be able to activate the same reporter. Consistent with previous literature, cleavage site motifs were generally highly conserved (74 - 76) and similar to our reporter sequence (Fig. 4B). To experimentally test their respective reporter cleavage abilities, we co-transfected our reporter into cells with each CoV Mpro expression plasmid individually. As expected, fluorescent reporter signal was observed, and quantification of reporter signal showed that each CoV Mpro effectively activated our reporter system, albeit to varying degrees, likely due to differences in catalysis efficiency across enzymes (Fig. 4C and D).

Fig 4.

Inhibition profile of diverse CoV Mpro proteases by nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir can be assessed using the FKBP-FlipGFP reporter. (A) Phylogenetic tree of eighteen beta-, alpha-, delta-, and gammacoronavirus Mpro sequences. Bootstrap values are listed at each node, and percentage of amino acid similarity is shown to the right of the virus strain name along with cartoon of the predominant host species. (B) Alignment showing sequence identity (black) and similarity (gray) of CoV Mpro cleavage sites with logo plots below showing consensus at each site (Nsp4/5 left, Nsp5/6 right). The logo plot of both Nsp4/5 and Nsp5/6 sites combined (far right) compared to the reporter sequence with highly conserved residues boxed in red. (C) Images of visible fluorescent reporter signal in 293Ts 24 h post-transfection with reporter and the indicated CoV Mpro. Green, cleaved FKBP-FlipGFP; blue, nuclei; scale bar = 100 µm. (D) Quantification of reporter signal in 293T cells shown in panel C. (E) Normalized reporter signal in 293T cells treated with 2 µM P-glycoprotein inhibitor and 10 µM nirmatrelvir, 24 h post-transfection with reporter and the indicated CoV Mpro. Values normalized to DMSO-vehicle. (F) Normalized reporter signal in 293T cells treated with 2 µM P-glycoprotein inhibitor and 10 µM ensitrelvir, 24 h post-transfection with reporter and the indicated CoV Mpro. Values normalized to DMSO-vehicle. (G to I) Normalized reporter signal in 293T cells 24 h post-transfection with reporter and the indicated CoV Mpro, treated with varying concentrations of nirmatrelvir (solid line) or ensitrelvir (dashed line). (G) Transfection of reporter with WT SARS-CoV-2 (green) or HKU9 (blue) Mpro. (H) Transfection of reporter with WT SARS-CoV-2 (green) or HKU8 (purple) Mpro. (I) Transfection of reporter with WT SARS-CoV-2 (green) or HKU19 (orange) Mpro. For all panels, data are shown as means with SEMs from independent biological replicates of 4. P values were calculated using multiple Mann–Whitney U tests (*, P < 0.05; ns, not significant).

We next wanted to define the “inhibitory profile” of nirmatrelvir against our broad Mpro panel. As expected, nirmatrelvir strongly inhibited reporter signal with WT SARS-CoV-2, and our negative control catalytically dead C145A mutant did not induce reporter signal with or without drug (Fig. 4E). The selected SARS-CoV-2 PAXLOVID-resistant mutants that we included—S144A, E166V + L50F, and W207L—all exhibited varying levels of inhibition consistent with our previous experiments. Notably, the rest of the betacoronaviruses showed a general trend of resistance to nirmatrelvir that was gradually reduced as they became less related to SARS-CoV-2. These findings are generally consistent with other reports (62, 77). The alphacoronaviruses displayed varying susceptibility to nirmatrelvir inhibition, with bat CoV CDPHE15 displaying the highest inhibition and others such as bat CoV CHB25 and human CoVs 2293 and NL63 displaying ~15–30% inhibition of reporter signal, which again is consistent with other reports (65, 77). Notably, rat CoV Lucheng19 and bat CoVs HKU8 and HKU33 displayed no inhibition of reporter signal. The deltacoronaviruses and gammacoronaviruses also displayed varying levels of inhibition, with night heron CoV HKU19 and beluga whale CoV SW1 displaying ~75% inhibition, bulbul CoV HKU11 displaying ~25% inhibition, and PDCOV and avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) displaying no inhibition. As an additional control, we included transfection of our ZIKV reporter and protease with nirmatrelvir, which showed no inhibition.

As a comparison, we wanted to define the inhibitory profile of another SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor, ensitrelvir (also known as S-217622), which has also shown clinical efficacy (13, 59, 78). Similar to nirmatrelvir, WT SARS-CoV-2 was strongly inhibited, and the negative control SARS-CoV-2 C145A showed no activity with or without drug (Fig. 4F). Interestingly, while the W207L mutant showed only slightly less inhibition compared to nirmatrelvir, the S144A and E166V + L50F mutants showed significant differences. The S144A mutant showed almost no inhibition of reporter signal when treated with ensitrelvir, compared to ~75% inhibition with nirmatrelvir. More notably, the E166V + L50F, which was completely resistant to inhibition by nirmatrelvir, was efficiently inhibited by ensitrelvir. Most of the betacoronaviruses showed varying levels of inhibition of reporter signal, not necessarily following the same correlation of inhibition and sequence homology as observed with nirmatrelvir. These data generally agreed with a recent study, with the exception of OC43 and 229E, for which we observed no appreciable inhibition (79). Remarkably, HKU9, which was strongly inhibited by nirmatrelvir, displayed no significant inhibition by ensitrelvir. The alphacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses did not display any significant inhibition of reporter signal by ensitrelvir, and the gammacoronaviruses only displayed slight inhibition of reporter signal with the SW1 Mpro. In some cases, activity with drug treatment was slightly increased, which may be explained by previous work showing that low amounts of protease inhibitors can influence protein dimerization in ways that can affect overall catalysis (80). As in the nirmatrelvir experiments, the ZIKV reporter and protease showed no inhibition of signal with ensitrelvir.

Finally, we wanted to perform a more in-depth analysis of the specific drug sensitivity of Mpros that had displayed differential susceptibility to nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir. To test this, we transfected our reporter and protease for the bat CoVs HKU9 and HKU8, and the avian CoV HKU19 into cells and treated with varying concentrations of either nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir (Fig. 4G to I). While cell viability remained mostly unimpacted at all concentrations for each CoV Mpro, reporter signal with SARS-CoV-2 was inhibited as expected for nirmatrelvir, and a similar IC50 was observed for ensitrelvir. HKU9 displayed strong reporter signal inhibition by nirmatrelvir with an IC50 = 1.70 µM, yet minimal inhibition by ensitrelvir with an IC50 = 137.6 µM. HKU8 displayed some inhibition at the highest concentrations of nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir, but minimal inhibition at all other concentrations. HKU19 was found to be moderately inhibited by nirmatrelvir with an IC50 = 3.41 µM, but only inhibited by ensitrelvir at the highest concentration of drug (100 µM). Together, these data demonstrate that the FKBP-FlipGFP assay can be used to understand the susceptibility of diverse CoVs to candidate inhibitors without the requirements for culturing the parent viruses.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to develop an improved fluorescent reporter assay to report on viral proteases and their inhibition by antivirals. We show that our FKBP-FlipGFP reporter system has minimal background signal and high dynamic range in reporter signal and can also be effectively used to report on the activity of numerous other viral proteases, such as SARS-Cov-2 PLpro, ZIKV NS2B-NS3, and EBV BVRF2. We confirmed our reporter system is a highly manipulatable, fast, and safe way to investigate the drug sensitivity of clinically relevant nirmatrelvir-resistant Mpro mutants without the need for live virus generation. Furthermore, we not only investigated the Mpro mutants’ specific drug sensitivity to nirmatrelvir but also tested their sensitivity to another antiviral, ensitrelvir. Lastly, we confirmed that our assay could be used to report on the activity of a diverse panel of human and nonhuman CoVs and each of their unique inhibition profiles by nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir. To our knowledge, for many of the CoVs in our panel, this is the first report investigating their susceptibility to nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir.

While our assay can report on CoV Mpro activity in living human cells (allowing simultaneous evaluation of drug permeability and toxicity), there are potential limitations compared to live viral assays that should be considered. Perhaps the most obvious is that during viral infection, a full complement of viral proteins is present, whereas here we only express the viral protease. Any interactions between the viral protease and other viral or host factors that could influence protease activity or drug accessibility is absent and would not be accounted for in our assay. Additionally, we are expressing a soluble protease that presumably diffuses across the cell and cleavage can occur anywhere, whereas during viral infection the viral replicative processes are occurring in highly structured replication complexes at the ER (81); thus, the subcellular microenvironment of cleavage as well as drug accessibility, again, may be different compared to our assay.

Another important consideration for interpreting our assay results is that the concentration of the plasmid-expressed protease in our system may be different (and likely higher) than those during viral infection, which may explain why our assay appears less sensitive for assessing drug inhibition compared to some live virus assays. Further, the relative expression and stability of different viral proteases is likely different, implying that sensitivity differences compared to infection may not be uniform across the assay. Indeed, we observed differences in “sensitivity patterns” with less observed inhibition of OC43 and 229E compared to SARS-like viruses after ensitrelvir treatment, but relatively more inhibition than expected with MERS-CoV compared to other human CoVs after nirmatrelvir treatment, based on previous reports (62, 79). Finally, it is important to note that we assess the activity of our diverse panel of CoV Mpros in one human cell type, which may not be optimal for each individual viral protease (especially the nonhuman CoV proteases). Thus, while the reporter assay has some clear advantages to live viral systems, it is important that experimental observations be considered hypothesis-generating and requiring further validation with orthogonal assays.

As is apparent from historical and contemporary coronavirus epidemics and pandemics, coronaviruses are important respiratory viral pathogens. Understanding the activity of our current antivirals against mutant strains of already circulating strains of viruses, as well as possible preemergent CoVs, is vital to our preparation for the next pandemic. The continued use of reporter assays such as the one we describe here has the potential to help answer these questions and also support the development of novel antivirals with broad-spectrum activity against CoVs that may be used to prevent or limit another pandemic outbreak.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The original coronavirus Mpro FlipGFP reporter was described previously (24). The improved coronavirus Mpro FKBP-FlipGFP reporter and pLex-FlipGFP β1–9 template DNA sequences were generated via gBlock gene synthesis (IDT). Compared to the original reporter, three major changes were made: (1) an FKBP L106P fusion ORF was added to the N-terminus, (2) a second viral protease cleavage site to allow removal of the FKBP protein was added, and (3) a GSG linker was added before the original 2A site (Supplemental Data). Reporters for CoV PLpro, ZIKV NS2B-NS3, and EBV protease BVRF2 were generated containing their respective cleavage sequences but were otherwise identical to the CoV Mpro FKBP-FlipGFP reporter (Supplemental Data). All protease sequences were obtained through NCBI and cloned into pLex expression plasmids using codon-optimized gBlocks (IDT) (Accession numbers: SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, MT020880.1; SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, MN 985325.1; ZIKV NS2B3, KX087101.3; EBV BVRF2, NC_007605.1; SARS-CoV-1, KY417145.1; NL63, DQ445912; MERS-CoV, KU740200.1; OC43, NC_006213, 229E, AGW80947.1; HKU1, ON128612; CDPHE15, NC_022103; HKU8, NC_010438; HKU9, NC_009021; HKU11, NC_011547; HKU19, NC_016994; HKU33, MK720944; Lucheng-19, NC_032730; CHB25, MN611525; SW1, NC_010646; PDCOV, KX022605; IBV, NP_066134.1). The CoV Mpro ORFs were cloned as the matured polypeptide sequence with an artificial initiator, methionine. The genes for (or the active protease domains of) the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, EBV BVRF2, and soluble ZIKV NS2B3 were based on previous expression construct designs (49, 53, 82, 83). SARS-CoV-2 nirmatrelvir-resistant mutants were all constructed on the USA/WA-1/2020 background. For all clones, PCR products were inserted into the pLex-expression vector using the BamHI and either XhoI or NotI restriction sites and HiFi DNA assembly (New England BioLabs [NEB]). DNA was transformed into chemically competent NEB 5-alpha high-efficiency cells (NEB, Cat. C2987H), and purified plasmids were confirmed using Sanger sequencing.

Cell culture

293T cells were originally obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. The 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, GlutaMAX, and penicillin-streptomycin, and kept at a low passage number (<15).

Transfections

For transfection, plates were poly-L-lysine-treated and seeded with 293Ts. After 24 h, plasmid DNA was combined with Opti-MEM and LipofectamineT 3000 (Invitrogen, Cat. L3000001) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, before being added dropwise to cells. For transfections including drug, a P-glycoprotein inhibitor, CP-100356, was included at the final concentration of 2 µM to limit efflux of drug from the cells. CP-100356 was resuspended in DMSO, then diluted in medium, and added dropwise to the cells before the transfection mix. Then, drugs (nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir) were initially resuspended in DMSO to 10 mM, then diluted in medium. This drug/medium or DMSO-vehicle/medium mix was then added to cells after the addition of the transfection mix to bring the total medium to the intended drug concentration.

Compounds

Nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332) was purchased from MedChemExpress (Cat. HY-138687), Ensitrelvir (fumarate) (S-217622) was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Cat. 35844), and P-glycoprotein inhibitor CP-100356 monohydrochloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat. PZ0171). All drugs were resuspended in DMSO, aliquoted, and kept at −20°C.

Imaging and quantification

At the intended timepoint, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 10 min. Cells were then incubated in 1:10,000 Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies, Cat. H3570) in 1× phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C overnight. Images were then obtained using the ZOE fluorescent cell imager (Bio-Rad), and quantification was performed using the Cell Insight CX5 platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A compartmental analysis protocol was used on the Cell Insight CX5 to capture the total live cell count stained by Hoechst 3342, as well as the percentage of the well that was GFP positive and the mean intensity of GFP signal. The latter parameters were then multiplied and used to calculate the reporter signal. This calculation of reporter signal importantly takes into account both the number of cells that are GFP+ as well as their overall brightness, allowing for increased dynamic range.

Sequence and structural analyses

For phylogenetic analysis, coronavirus Mpro amino acid sequences were aligned using the Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation (MUSCLE). A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with IQ-Tree (v1.6.12) using automatic model selection and 10,000 ultra-fast bootstraps. Sequence similarity was calculated using the Sequence Manipulation Suite. Multisequence alignments for consensus sequence site alignments were performed using CLUSTALW with shading at 50% identity or similarity on the Boxshade v3.3 software. Sequence logo plots were made using WebLogo 3 software (84, 85). All protein visualization and figure image generation were performed with UCSF Chimera protein modeling software (PDBs: SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with nirmatrelvir, 8DZ2; SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, 7NFV; ZIKV NSB2-NS3, 7VXX; EBV viral protease, 1O6E) (86).

Statistical analysis and graphing

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software, and the statistical analysis used to compare groups is indicated in the figure legends. All experiments were performed in biological replicates of four independent experiments, and significance values were determined using Mann–Whitney U tests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Sam Skavicus and Katie Burke for their help with plasmid generation, and Dr. So Young Kim and the Functional Genomics Core Facility for assistance with high-content imaging.

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U19AI171292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. N.S.H. also holds an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. R.A.L. is partially supported by the training grant T32-CA009111. Duke University has filed for intellectual property protection of some of the work described in this study. Schematics were created using BioRender.com.

Contributor Information

Nicholas S. Heaton, Email: nicholas.heaton@duke.edu.

Stacey Schultz-Cherry, St Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, USA .

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00597-23.

Fig. S1 to S4.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kozlakidis Z. 2022. Evidence for recombination as an evolutionary mechanism in coronaviruses: Is SARS-CoV-2 an exception?. Front Public Health 10:859900. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.859900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. 2020. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, Munster VJ. 2016. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chafekar A, Fielding BC. 2018. MERS-CoV: understanding the latest human coronavirus threat. Viruses 10:93. doi: 10.3390/v10020093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iketani S, Liu L, Guo Y, Liu L, Chan J-W, Huang Y, Wang M, Luo Y, Yu J, Chu H, Chik K-H, Yuen T-T, Yin MT, Sobieszczyk ME, Huang Y, Yuen K-Y, Wang HH, Sheng Z, Ho DD. 2022. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 604:553–556. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04594-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Q, Guo Y, Iketani S, Nair MS, Li Z, Mohri H, Wang M, Yu J, Bowen AD, Chang JY, Shah JG, Nguyen N, Chen Z, Meyers K, Yin MT, Sobieszczyk ME, Sheng Z, Huang Y, Liu L, Ho DD. 2022. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 608:603–608. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05053-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, Iketani S, Luo Y, Guo Y, Wang M, Yu J, Zhang B, Kwong PD, Graham BS, Mascola JR, Chang JY, Yin MT, Sobieszczyk M, Kyratsous CA, Shapiro L, Sheng Z, Huang Y, Ho DD. 2021. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 593:130–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, Abreu P, Bao W, Wisemandle W, Baniecki M, Hendrick VM, Damle B, Simón-Campos A, Pypstra R, Rusnak JM, Investigators E-H . 2022. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 386:1397–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, Kovalchuk E, Gonzalez A, Delos Reyes V, Martín-Quirós A, Caraco Y, Williams-Diaz A, Brown ML, Du J, Pedley A, Assaid C, Strizki J, Grobler JA, Shamsuddin HH, Tipping R, Wan H, Paschke A, Butterton JR, Johnson MG, De Anda C, MOVe-OUT Study Group . 2022. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of COVID-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 386:509–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, Tomashek KM, Wolfe CR, Ghazaryan V, Marconi VC, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Hsieh L, Kline S, Tapson V, Iovine NM, Jain MK, Sweeney DA, El Sahly HM, Branche AR, Regalado Pineda J, Lye DC, Sandkovsky U, Luetkemeyer AF, Cohen SH, Finberg RW, Jackson PEH, Taiwo B, Paules CI, Arguinchona H, Erdmann N, Ahuja N, Frank M, Oh M-D, Kim E-S, Tan SY, Mularski RA, Nielsen H, Ponce PO, Taylor BS, Larson L, Rouphael NG, Saklawi Y, Cantos VD, Ko ER, Engemann JJ, Amin AN, Watanabe M, Billings J, Elie M-C, Davey RT, Burgess TH, Ferreira J, Green M, Makowski M, Cardoso A, de Bono S, Bonnett T, Proschan M, Deye GA, Dempsey W, Nayak SU, Dodd LE, Beigel JH, ACTT-2 Study Group Members . 2020. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 - final report. N Engl J Med 383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Banerjee A, Mossman K, Grandvaux N. 2021. Molecular determinants of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Trends Microbiol 29:871–873. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alteri C, Fox V, Scutari R, Burastero GJ, Volpi S, Faltoni M, Fini V, Granaglia A, Esperti S, Gallerani A, Costabile V, Fontana B, Franceschini E, Meschiari M, Campana A, Bernardi S, Villani A, Bernaschi P, Russo C, Guaraldi G, Mussini C, Perno CF. 2022. A proof-of-concept study on the genomic evolution of Sars-CoV-2 in molnupiravir-treated, paxlovid-treated and drug-naïve patients. Commun Biol 5:1376. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-04322-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuroda T, Nobori H, Fukao K, Baba K, Matsumoto K, Yoshida S, Tanaka Y, Watari R, Oka R, Kasai Y, Inoue K, Kawashima S, Shimba A, Hayasaki-Kajiwara Y, Tanimura M, Zhang Q, Tachibana Y, Kato T, Shishido T. 2023. Efficacy comparison of 3CL protease inhibitors ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and in vivo. J Antimicrob Chemother 78:946–952. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkad027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iketani S, Mohri H, Culbertson B, Hong SJ, Duan Y, Luck MI, Annavajhala MK, Guo Y, Sheng Z, Uhlemann A-C, Goff SP, Sabo Y, Yang H, Chavez A, Ho DD. 2023. Multiple pathways for SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature 613:558–564. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05514-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou Y, Gammeltoft KA, Ryberg LA, Pham LV, Tjørnelund HD, Binderup A, Duarte Hernandez CR, Fernandez-Antunez C, Offersgaard A, Fahnøe U, Peters GHJ, Ramirez S, Bukh J, Gottwein JM. 2022. Nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants with high fitness in an infectious cell culture system. Sci Adv 8:eadd7197. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.add7197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jochmans D, Liu C, Donckers K, Stoycheva A, Boland S, Stevens SK, De Vita C, Vanmechelen B, Maes P, Trüeb B, Ebert N, Thiel V, De Jonghe S, Vangeel L, Bardiot D, Jekle A, Blatt LM, Beigelman L, Symons JA, Raboisson P, Chaltin P, Marchand A, Neyts J, Deval J, Vandyck K. 2023. The substitutions L50F, E166A, and L167F in SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro are selected by a protease inhibitor in vitro and confer resistance to nirmatrelvir. mBio 14:e0281522. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02815-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu Y, Lewandowski EM, Tan H, Zhang X, Morgan RT, Zhang X, Jacobs LMC, Butler SG, Gongora MV, Choy J, Deng X, Chen Y, Wang J. 2022. Naturally occurring mutations of SARS-CoV-2 main protease confer drug resistance to nirmatrelvir. bioRxiv:2022.06.28.497978. doi: 10.1101/2022.06.28.497978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Iketani S, Hong SJ, Sheng J, Bahari F, Culbertson B, Atanaki FF, Aditham AK, Kratz AF, Luck MI, Tian R, Goff SP, Montazeri H, Sabo Y, Ho DD, Chavez A. 2022. Functional map of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease reveals tolerant and immutable sites. Cell Host Microbe 30:1354–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moghadasi SA, Heilmann E, Khalil AM, Nnabuife C, Kearns FL, Ye C, Moraes SN, Costacurta F, Esler MA, Aihara H, von Laer D, Martinez-Sobrido L, Palzkill T, Amaro RE, Harris RS. 2022. Transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants with resistance to clinical protease inhibitors. bioRxiv:2022.08.07.503099. doi: 10.1101/2022.08.07.503099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. Sacco MD, Hu Y, Gongora MV, Meilleur F, Kemp MT, Zhang X, Wang J, Chen Y. 2022. The P132H mutation in the main protease of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 decreases thermal stability without compromising catalysis or small-molecule drug inhibition. Cell Res 32:498–500. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00640-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heilmann E, Costacurta F, Moghadasi SA, Ye C, Pavan M, Bassani D, Volland A, Ascher C, Weiss AKH, Bante D, Harris RS, Moro S, Rupp B, Martinez-Sobrido L, von Laer D. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 3Clpro mutations selected in a VSV-based system confer resistance to nirmatrelvir, ensitrelvir, and GC376. Sci Transl Med 15:eabq7360. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq7360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moghadasi SA, Biswas RG, Harki DA, Harris RS. 2023. Rapid resistance profiling of SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitors. bioRxiv:2023.02.25.530000. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.25.530000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noske GD, de Souza Silva E, de Godoy MO, Dolci I, Fernandes RS, Guido RVC, Sjö P, Oliva G, Godoy AS. 2023. Structural basis of nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir activity against naturally occurring polymorphisms of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J Biol Chem 299:103004. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.103004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Froggatt HM, Heaton BE, Heaton NS. 2020. Development of a fluorescence-based, high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 3Clpro reporter assay. J Virol 94:e01265-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Min JS, Kim G-W, Kwon S, Jin Y-H. 2020. A cell-based reporter assay for screening inhibitors of MERS coronavirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity. J Clin Med 9:2399. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ju X, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang J, Gong M, Ren W, Li S, Zhong J, Zhang L, Zhang QC, Zhang R, Ding Q, Lee B. 2021. A novel cell culture system modeling the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009439. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Classen N, Ulrich D, Hofemeier A, Hennies MT, Hafezi W, Pettke A, Romberg M-L, Lorentzen EU, Hensel A, Kühn JE. 2022. Broadly applicable, virus-free dual reporter assay to identify compounds interfering with membrane fusion: performance for HSV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 14:1354. doi: 10.3390/v14071354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Resnick SJ, Iketani S, Hong SJ, Zask A, Liu H, Kim S, Melore S, Lin F-Y, Nair MS, Huang Y, Lee S, Tay NES, Rovis T, Yang HW, Xing L, Stockwell BR, Ho DD, Chavez A. 2021. Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3CL proteases protect cells from protease-mediated cytotoxicity. J Virol 95:e0237420. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02374-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Brien A, Chen DY, Hackbart M, Close BJ, O’Brien TE, Saeed M, Baker SC. 2021. Detecting SARS-CoV-2 3Clpro expression and activity using a polyclonal antiserum and a luciferase-based biosensor. Virology 556:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kilianski A, Mielech AM, Deng X, Baker SC. 2013. Assessing activity and inhibition of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like and 3C-like proteases using luciferase-based biosensors. J Virol 87:11955–11962. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02105-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang J, Xiao Y, Lidsky PV, Wu CT, Bonser LR, Peng S, Garcia-Knight MA, Tassetto M, Chung CI, Li X, Nakayama T, Lee IT, Nayak JV, Ghias K, Hargett KL, Shoichet BK, Erle DJ, Jackson PK, Andino R, Shu X. 2023. Fluorogenic reporter enables identification of compounds that inhibit SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol 8:121–134. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01288-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li X, Lidsky PV, Xiao Y, Wu CT, Garcia-Knight M, Yang J, Nakayama T, Nayak JV, Jackson PK, Andino R, Shu X. 2021. Ethacridine inhibits SARS-CoV-2 by Inactivating viral particles. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009898. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Narayanan A, Narwal M, Majowicz SA, Varricchio C, Toner SA, Ballatore C, Brancale A, Murakami KS, Jose J. 2022. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors targeting Mpro and PLpro using in-cell-protease assay. Commun Biol 5:169. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03090-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu M, Zhou J, Cheng Y, Jin Z, Clark AE, He T, Yim W, Li Y, Chang Y-C, Wu Z, Fajtová P, O’Donoghue AJ, Carlin AF, Todd MD, Jokerst JV. 2022. A self-immolative fluorescent probe for selective detection of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Anal Chem 94:11728–11733. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c02381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dey-Rao R, Smith GR, Timilsina U, Falls Z, Samudrala R, Stavrou S, Melendy T. 2021. A fluorescence-based, gain-of-signal, live cell system to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibition. Antiviral Res 195:105183. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moghadasi SA, Esler MA, Otsuka Y, Becker JT, Moraes SN, Anderson CB, Chamakuri S, Belica C, Wick C, Harki DA, Young DW, Scampavia L, Spicer TP, Shi K, Aihara H, Brown WL, Harris RS. 2022. Gain-of-signal assays for probing inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro/3CLpro in living cells. mBio 13:e0078422. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00784-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uppal T, Tuffo K, Khaiboullina S, Reganti S, Pandori M, Verma SC. 2022. Screening of SARS-CoV-2 antivirals through a cell-based RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) reporter assay. Cell Insight 1:100046. doi: 10.1016/j.cellin.2022.100046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Min JS, Kwon S, Jin Y-H. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 RdRp inhibitors selected from a cell-based SARS-CoV-2 RdRp activity assay system. Biomedicines 9:996. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9080996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao J, Guo S, Yi D, Li Q, Ma L, Zhang Y, Wang J, Li X, Guo F, Lin R, Liang C, Liu Z, Cen S. 2021. A cell-based assay to discover inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral Res 190:105078. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang Q, Schepis A, Huang H, Yang J, Ma W, Torra J, Zhang S-Q, Yang L, Wu H, Nonell S, Dong Z, Kornberg TB, Coughlin SR, Shu X. 2019. Designing a green fluorogenic protease reporter by flipping a beta strand of GFP for imaging apoptosis in animals. J Am Chem Soc 141:4526–4530. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Armstrong CM, Goldberg DE. 2007. An FKBP destabilization domain modulates protein levels in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Methods 4:1007–1009. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. An W, Jackson RE, Hunter P, Gögel S, van Diepen M, Liu K, Meyer MP, Eickholt BJ. 2015. Engineering FKBP-based destabilizing domains to build sophisticated protein regulation systems. PLoS One 10:e0145783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Banaszynski LA, Chen L-C, Maynard-Smith LA, Ooi AGL, Wandless TJ. 2006. A rapid, reversible, and tunable method to regulate protein function in living cells using synthetic small molecules. Cell 126:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chu BW, Banaszynski LA, Chen L, Wandless TJ. 2008. Recent progress with FKBP-derived destabilizing domains. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 18:5941–5944. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zephyr J, Kurt Yilmaz N, Schiffer CA. 2021. Viral proteases: structure, mechanism and inhibition. Enzymes 50:301–333. doi: 10.1016/bs.enz.2021.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arya R, Kumari S, Pandey B, Mistry H, Bihani SC, Das A, Prashar V, Gupta GD, Panicker L, Kumar M. 2021. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J Mol Biol 433:166725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ullrich S, Nitsche C. 2020. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 30:127377. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cannalire R, Cerchia C, Beccari AR, Di Leva FS, Summa V. 2022. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteases and polymerase for COVID-19 treatment: state of the art and future opportunities. J Med Chem 65:2716–2746. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shin D, Mukherjee R, Grewe D, Bojkova D, Baek K, Bhattacharya A, Schulz L, Widera M, Mehdipour AR, Tascher G, Geurink PP, Wilhelm A, van der Heden van Noort GJ, Ovaa H, Müller S, Knobeloch K-P, Rajalingam K, Schulman BA, Cinatl J, Hummer G, Ciesek S, Dikic I. 2020. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature 587:657–662. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2601-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Coluccia A, Puxeddu M, Nalli M, Wei CK, Wu YH, Mastrangelo E, Elamin T, Tarantino D, Bugert JJ, Schreiner B, Nolte J, Schwarze F, La Regina G, Lee JC, Silvestri R. 2020. Discovery of Zika virus NS2B/NS3 inhibitors that prevent mice from life-threatening infection and brain damage. ACS Med Chem Lett 11:1869–1874. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hilgenfeld R, Lei J, Zhang L. 2018. The structure of the zika virus protease, NS2B/NS3(Pro). Adv Exp Med Biol 1062:131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li Q, Kang C. 2021. Structure and dynamics of zika virus protease and its insights into inhibitor design. Biomedicines 9:1044. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9081044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Phoo WW, Li Y, Zhang Z, Lee MY, Loh YR, Tan YB, Ng EY, Lescar J, Kang C, Luo D. 2016. Structure of the NS2B-NS3 protease from zika virus after self-cleavage. Nat Commun 7:13410. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Buisson M, Hernandez J-F, Lascoux D, Schoehn G, Forest E, Arlaud G, Seigneurin J-M, Ruigrok RWH, Burmeister WP. 2002. The crystal structure of the Epstein-Barr virus protease shows rearrangement of the processed C terminus. J Mol Biol 324:89–103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01040-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Donaghy G, Jupp R. 1995. Characterization of the Epstein-Barr virus proteinase and comparison with the human cytomegalovirus proteinase. J Virol 69:1265–1270. doi: 10.1128/JVI.69.2.1265-1270.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shiryaev SA, Farhy C, Pinto A, Huang CT, Simonetti N, Elong Ngono A, Dewing A, Shresta S, Pinkerton AB, Cieplak P, Strongin AY, Terskikh AV. 2017. Characterization of the zika virus two-component NS2B-NS3 protease and structure-assisted identification of allosteric small-molecule antagonists. Antiviral Res 143:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gerber PP, Duncan LM, Greenwood EJ, Marelli S, Naamati A, Teixeira-Silva A, Crozier TW, Gabaev I, Zhan JR, Mulroney TE, Horner EC, Doffinger R, Willis AE, Thaventhiran JE, Protasio AV, Matheson NJ, Suthar M. 2022. A protease-activatable luminescent biosensor and reporter cell line for authentic SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010265. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Buisson M, Valette E, Hernandez JF, Baudin F, Ebel C, Morand P, Seigneurin JM, Arlaud GJ, Ruigrok RW. 2001. Functional determinants of the Epstein-Barr virus protease. J Mol Biol 311:217–228. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sasaki M, Tabata K, Kishimoto M, Itakura Y, Kobayashi H, Ariizumi T, Uemura K, Toba S, Kusakabe S, Maruyama Y, Iida S, Nakajima N, Suzuki T, Yoshida S, Nobori H, Sanaki T, Kato T, Shishido T, Hall WW, Orba Y, Sato A, Sawa H. 2023. S-217622, a SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor, decreases viral load and ameliorates COVID-19 severity in hamsters. Sci Transl Med 15:eabq4064. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq4064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Boras B, Jones RM, Anson BJ, Arenson D, Aschenbrenner L, Bakowski MA, Beutler N, Binder J, Chen E, Eng H, Hammond H, Hammond J, Haupt RE, Hoffman R, Kadar EP, Kania R, Kimoto E, Kirkpatrick MG, Lanyon L, Lendy EK, Lillis JR, Logue J, Luthra SA, Ma C, Mason SW, McGrath ME, Noell S, Obach RS, O’ Brien MN, O’Connor R, Ogilvie K, Owen D, Pettersson M, Reese MR, Rogers TF, Rosales R, Rossulek MI, Sathish JG, Shirai N, Steppan C, Ticehurst M, Updyke LW, Weston S, Zhu Y, White KM, García-Sastre A, Wang J, Chatterjee AK, Mesecar AD, Frieman MB, Anderson AS, Allerton C. 2021. Preclinical characterization of an intravenous coronavirus 3CL protease inhibitor for the potential treatment of COVID19. Nat Commun 12:6055. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26239-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. He X, Quan S, Xu M, Rodriguez S, Goh SL, Wei J, Fridman A, Koeplinger KA, Carroll SS, Grobler JA, Espeseth AS, Olsen DB, Hazuda DJ, Wang D. 2021. Generation of SARS-CoV-2 reporter replicon for high-throughput antiviral screening and testing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118:e2025866118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2025866118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Owen DR, Allerton CMN, Anderson AS, Aschenbrenner L, Avery M, Berritt S, Boras B, Cardin RD, Carlo A, Coffman KJ, Dantonio A, Di L, Eng H, Ferre R, Gajiwala KS, Gibson SA, Greasley SE, Hurst BL, Kadar EP, Kalgutkar AS, Lee JC, Lee J, Liu W, Mason SW, Noell S, Novak JJ, Obach RS, Ogilvie K, Patel NC, Pettersson M, Rai DK, Reese MR, Sammons MF, Sathish JG, Singh RSP, Steppan CM, Stewart AE, Tuttle JB, Updyke L, Verhoest PR, Wei L, Yang Q, Zhu Y. 2021. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science 374:1586–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rosales R, McGovern BL, Rodriguez ML, Rai DK, Cardin RD, Anderson AS, Sordillo EM, van Bakel H, Simon V, García-Sastre A, White KM, PSP study group . 2022. Nirmatrelvir, molnupiravir, and remdesivir maintain potent in vitro activity against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Microbiology. doi: 10.1101/2022.01.17.476685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fiaschi L, Dragoni F, Schiaroli E, Bergna A, Rossetti B, Giammarino F, Biba C, Gidari A, Lai A, Nencioni C, Francisci D, Zazzi M, Vicenti I. 2022. Efficacy of licensed monoclonal antibodies and antiviral agents against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages BA.1 and BA.2. Viruses 14:1374. doi: 10.3390/v14071374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li J, Wang Y, Solanki K, Atre R, Lavrijsen M, Pan Q, Baig MS, Li P. 2023. Nirmatrelvir exerts distinct antiviral potency against different human coronaviruses. Antiviral Research 211:105555. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li P, Wang Y, Lavrijsen M, Lamers MM, de Vries AC, Rottier RJ, Bruno MJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Haagmans BL, Pan Q. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res 32:322–324. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00618-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Administration UFaD . 2023. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: emergency use authorization for paxlovid. Administration Ufad. https://www.fda.gov/media/155050/download. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Padhi AK, Tripathi T. 2022. Hotspot residues and resistance mutations in the nirmatrelvir-binding site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: design, identification, and correlation with globally circulating viral genomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 629:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cockrell AS, Beall A, Yount B, Baric R. 2017. Efficient reverse genetic systems for rapid genetic manipulation of emergent and preemergent infectious coronaviruses. Methods Mol Biol 1602:59–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6964-7_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Corman VM, Muth D, Niemeyer D, Drosten C. 2018. Hosts and sources of endemic human coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res 100:163–188. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dhama K, Patel SK, Sharun K, Pathak M, Tiwari R, Yatoo MI, Malik YS, Sah R, Rabaan AA, Panwar PK, Singh KP, Michalak I, Chaicumpa W, Martinez-Pulgarin DF, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 jumping the species barrier: zoonotic lessons from SARS, MERS and recent advances to combat this pandemic virus. Travel Med Infect Dis 37:101830. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Brown AJ, Won JJ, Graham RL, Dinnon KH 3rd, Sims AC, Feng JY, Cihlar T, Denison MR, Baric RS, Sheahan TP. 2019. Broad spectrum antiviral remdesivir inhibits human endemic and zoonotic deltacoronaviruses with a highly divergent RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral Res 169:104541. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.104541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, Robertson DL, Crits-Christoph A, Wertheim JO, Anthony SJ, Barclay WS, Boni MF, Doherty PC, Farrar J, Geoghegan JL, Jiang X, Leibowitz JL, Neil SJD, Skern T, Weiss SR, Worobey M, Andersen KG, Garry RF, Rambaut A. 2021. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: a critical review. Cell 184:4848–4856. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen H, Zhu Z, Qiu Y, Ge X, Zheng H, Peng Y. 2022. Prediction of coronavirus 3C-like protease cleavage sites using machine-learning algorithms. Virol Sin 37:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chuck C-P, Chow H-F, Wan DC-C, Wong K-B. 2011. Profiling of substrate specificities of 3C-like proteases from group 1, 2a, 2b, and 3 coronaviruses. PLoS One 6:e27228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hegyi A, Ziebuhr J. 2002. Conservation of substrate specificities among coronavirus main proteases. J Gen Virol 83:595–599. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Weil T, Lawrenz J, Seidel A, Münch J, Müller JA. 2022. Immunodetection assays for the quantification of seasonal common cold coronaviruses OC43, NL63, or 229E infection confirm nirmatrelvir as broad coronavirus inhibitor. Antiviral Res 203:105343. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mukae H, Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, Doi Y, Imamura T, Sonoyama T, Fukuhara T, Ichihashi G, Sanaki T, Baba K, Takeda Y, Tsuge Y, Uehara T. 2022. A randomized phase 2/3 study of ensitrelvir, a novel oral SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitor, in Japanese patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: results of the phase 2A part. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66. doi: 10.1128/aac.00697-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Unoh Y, Uehara S, Nakahara K, Nobori H, Yamatsu Y, Yamamoto S, Maruyama Y, Taoda Y, Kasamatsu K, Suto T, Kouki K, Nakahashi A, Kawashima S, Sanaki T, Toba S, Uemura K, Mizutare T, Ando S, Sasaki M, Orba Y, Sawa H, Sato A, Sato T, Kato T, Tachibana Y. 2022. Discovery of S-217622, a Noncovalent oral SARS-Cov-2 3Cl protease inhibitor clinical candidate for treating COVID-19. J Med Chem 65:6499–6512. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tomar S, Johnston ML, St John SE, Osswald HL, Nyalapatla PR, Paul LN, Ghosh AK, Denison MR, Mesecar AD. 2015. Ligand-induced dimerization of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus nsp5 protease (3Clpro): implications for nsp5 regulation and the development of antivirals. J Biol Chem 290:19403–19422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.651463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Malone B, Urakova N, Snijder EJ, Campbell EA. 2022. Structures and functions of coronavirus replication-transcription complexes and their relevance for SARS-CoV-2 drug design. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23:21–39. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00432-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Osipiuk J, Azizi SA, Dvorkin S, Endres M, Jedrzejczak R, Jones KA, Kang S, Kathayat RS, Kim Y, Lisnyak VG, Maki SL, Nicolaescu V, Taylor CA, Tesar C, Zhang YA, Zhou Z, Randall G, Michalska K, Snyder SA, Dickinson BC, Joachimiak A. 2021. Structure of papain-like protease from SARS-CoV-2 and its complexes with non-covalent inhibitors. Nat Commun 12:743. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21060-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hulce KR, Jaishankar P, Lee GM, Bohn MF, Connelly EJ, Wucherer K, Ongpipattanakul C, Volk RF, Chuo SW, Arkin MR, Renslo AR, Craik CS. 2022. Inhibiting a dynamic viral protease by targeting a non-catalytic cysteine. Cell Chem Biol 29:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schneider TD, Stephens RM. 1990. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucl Acids Res 18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S4.