ABSTRACT

With increasing resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to antibodies, there is interest in developing entry inhibitors that target essential receptor-binding regions of the viral Spike protein and thereby present a high bar for viral resistance. Such inhibitors could be derivatives of the viral receptor, ACE2, or peptides engineered to interact specifically with the Spike receptor-binding pocket. We compared the efficacy of a series of both types of entry inhibitors, constructed as fusions to an antibody Fc domain. Such a design can increase protein stability and act to both neutralize free virus and recruit effector functions to clear infected cells. We tested the reagents against prototype variants of SARS-CoV-2, using both Spike pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus vectors and replication-competent viruses. These analyses revealed that an optimized ACE2 derivative could neutralize all variants we tested with high efficacy. In contrast, the Spike-binding peptides had varying activities against different variants, with resistance observed in the Spike proteins from Beta, Gamma, and Omicron (BA.1 and BA.5). The resistance mapped to mutations at Spike residues K417 and N501 and could be overcome for one of the peptides by linking two copies in tandem, effectively creating a tetrameric reagent in the Fc fusion. Finally, both the optimized ACE2 and tetrameric peptide inhibitors provided some protection to human ACE2 transgenic mice challenged with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, which typically causes death in this model within 7–9 days.

IMPORTANCE

The increasing resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to therapeutic antibodies has highlighted the need for new treatment options, especially in individuals who do not respond to vaccination. Receptor decoys that block viral entry are an attractive approach because of the presumed high bar to developing viral resistance. Here, we compare two entry inhibitors based on derivatives of the ACE2 receptor, or engineered peptides that bind to the receptor-binding pocket of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein. In each case, the inhibitors were fused to immunoglobulin Fc domains, which can further enhance therapeutic properties, and compared for activity against different SARS-CoV-2 variants. Potent inhibition against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants was demonstrated in vitro, and even relatively low single doses of optimized reagents provided some protection in a mouse model, confirming their potential as an alternative to antibody therapies.

KEYWORDS: SARS-CoV-2, entry inhibitor, ACE2, Spike

INTRODUCTION

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has spread globally since first identified in Wuhan, China in 2019 (1). By Fall 2022, more than 637 million cases and 6.62 million deaths had been reported (2). Contributing to this pandemic has been the emergence of distinct viral variants, of which the World Health Organization has designated several as variants of concern: Alpha (B.1.1.7, first detected in the UK in 2020), Beta (B.1.351, from South Africa in 2020), Gamma (P.1, from Brazil in 2021), Delta (B.1.617.2, from India in 2021), and Omicron BA.1 (B.1.1.539, from multiple countries in 2021). Omicron BA.1 has continued to produce new subvariants such as BA.2, BA.4, and BA.5, which have caused waves of infection since December 2021, with subvariant XBB.1.5 being dominant in the US in early 2023 (3).

To combat this public health emergency, vaccines, monoclonal antibody treatments, and antiviral drugs have been rapidly developed (4, 5). While vaccines have proven successful at preventing serious illness and death, they do not absolutely prevent infection. Early studies reported a diminished ability of vaccine-induced antibodies to neutralize Beta and Gamma variants (6, 7). Similarly, Omicron subvariants have proven effective in evading antibodies resulting from vaccination or prior infections (8, 9). More recently, bivalent vaccines containing both ancestral and BA.4/5 Spike sequences have shown improved humoral responses against Omicron subvariants including XBB.1.5 (9). At the same time, the extensive mutations present in the Omicron Spike protein have significantly reduced the effectiveness of monoclonal antibody therapies (9 - 12), underscoring the need to develop alternate, broadly acting vaccines and therapeutics with activity against both current and future viral variants (13).

SARS-CoV-2 enters cells following the interaction of its Spike protein with cell surface angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (1). Viral receptors can be repurposed as entry inhibitors, being expressed either as soluble receptor domains or further stabilized by fusion to other proteins such as immunoglobulin (Ig) Fc domains (14, 15). The underlying assumption is that a virus would not be able to evolve resistance to an inhibitor that mimics the interaction with its cellular receptor without a significant loss of fitness. Both soluble ACE2 and ACE2-Ig fusions have been reported as effective inhibitors of entry directed by the Spike proteins from SARS-CoV-1 (16 - 19) and SARS-CoV-2 (16, 17, 20 - 44). To prevent interference with the normal function of ACE2 in regulating blood pressure, these antiviral reagents often contain mutations in the protein’s catalytic domain (18). Studies have also identified additional mutations in ACE2 that enhance binding to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike, increasing neutralization in in vitro assays by 100- to 300-fold (20 - 28 - 40 - 43 - 43). Of note, binding-enhanced ACE2-Ig constructs have shown activity against different variants of concern, including Omicron (26, 30, 33, 35, 41 - 44). Finally, ACE2-Ig constructs have been reported to provide some protection following SARS-CoV-2 challenge of hamsters (20, 30, 36) and human ACE2 transgenic mice (22, 24, 30, 32, 34, 35, 41, 43, 44).

An alternative approach to inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 entry has been to use small Spike-binding peptides (SBPs), engineered to target the essential receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the protein (45 - 48). These SBPs can prevent infection at picomolar levels in vitro and are protective when given to mice as either the peptides alone (46), when fused to an Fc domain (46), or when trimerized to match the oligomeric form of the Spike protein (47).

In the present study, we compared the potency and breadth of activity of a binding-enhanced ACE2-Ig inhibitor and a series of constructs comprising SBPs fused to antibody Fc domains (SBP-Ig). We tested the reagents against pseudoviruses containing SARS-CoV-2 Spike proteins from both the early emerging D614G variant (49 - 51) and representatives of each of the major variants of concern. We found that while the enhanced ACE2-Ig derivative could block entry by all Spike proteins we tested with similar picomolar efficacy, the two SBP-Ig inhibitors were sensitive to the mutations acquired by the Beta, Gamma, and Omicron BA.1 variants. Interestingly, presentation of one of the small peptides as a tandem repeat was able to overcome this resistance, restoring broad activity to this class of reagents and agreeing with previous reports of the superior activity of multimeric peptide designs (47). Finally, single injections of both the modified ACE2-Ig construct and a tandem SBP-Ig reagent showed some protection in mice challenged with the Delta variant, with the multimerized SBP-Ig giving a higher survival rate.

RESULTS

Optimization of ACE2-Ig for neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein

To identify an optimal ACE2-Ig entry inhibitor, we first compared constructs comprising residues 1–740 of the ACE2 ectodomain fused to IgG1 Fc and a shorter version, truncated at residue 615, that excluded the ACE2 collectrin-like domain. In both cases, a catalytically dead ACE2 variant was used that does not cleave the angiotensin- (1 - 8) peptide (18). Previously, an ACE2-Ig construct comprising residues 18–740 was found to have superior neutralizing activity than a 18-615 version against pseudoviruses carrying the original SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan Spike protein (17). We also observed that our longer 1-740 version was superior to the 1-615 version in neutralization studies using pseudoviruses carrying the D614G Spike protein, which was an early dominant variant of SARS-CoV-2, with enhanced infectivity and spread (49 - 51) (Fig. S1).

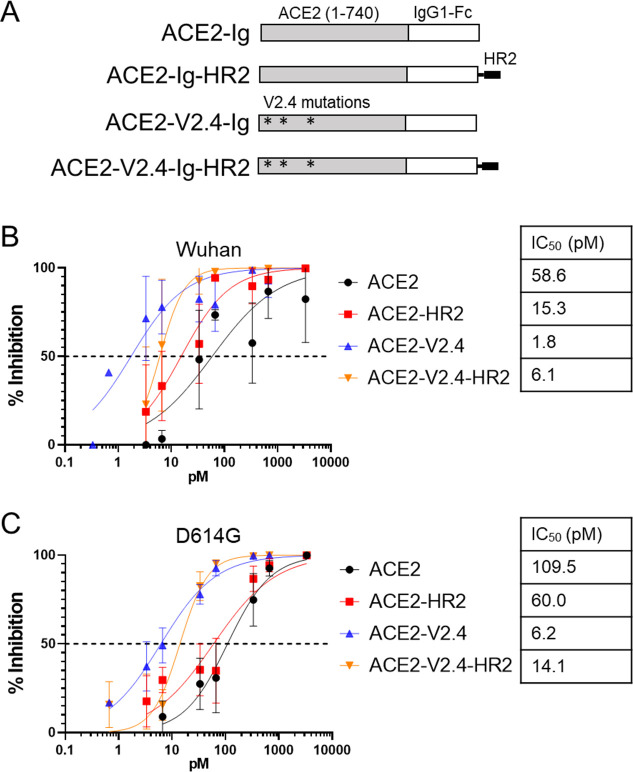

The potency of ACE2 receptor decoys can be increased by mutations that enhance binding to the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (20 - 28 - 40 - 43 - 44 - 44). We selected the V2.4 mutation group (T27Y, L79T, and N330Y), which was reported to enhance binding by 35-fold due to higher affinity and lower dissociation rates (28), and protected mice from an infectious challenge when delivered as either the soluble protein or fused to an Fc domain (28, 44). In addition, we attempted to further enhance the ACE2-Ig constructs by inclusion of a heptad repeat-2 (HR2) peptide fusion inhibitor (52) at the C-terminus of the Fc domain (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

ACE2-binding enhancing mutations, but not HR2, increase neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Spike. (A) Schematic of different ACE2-Ig constructs. (B) Neutralization of VSV vectors pseudotyped with the Wuhan variant Spike protein by indicated amounts of different ACE2-Ig constructs. Error bars are SEM from n = 3 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. (C) Neutralization assay for VSV pseudovirus containing the D614G Spike variant. Error bars are SEM from n = 4 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves are shown in Table S1.

To test these various entry inhibitors, we used a Spike pseudovirus system that we have previously optimized (53). Here, full-length SARS-CoV-2 Spike proteins are incorporated into replication-incompetent vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) vectors that express luciferase upon entry, and the vectors are used to transduce HeLa cells expressing ACE2 (53), which give reproducible titration results when infected with SARS-CoV-2 (54). Using this system, we compared the ability of the series of ACE2-Ig constructs to inhibit entry directed by pseudoviruses containing the Spike proteins from either the original Wuhan isolate or the D614G variant. We found that the V2.4 mutations significantly enhanced inhibition by 18- to 33-fold against the D614G and Wuhan pseudoviruses, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). (The P-values for data shown in all figures are presented in Table S1). In contrast, addition of the HR2 peptide resulted in only a small enhancement of inhibition by the non-modified ACE2-Ig construct against Wuhan pseudoviruses only, while actually causing a significant decrease in inhibition for the ACE2-V2.4-Ig construct against both Wuhan and D614G. As a result, we moved forward with ACE2-V2.4-Ig as an optimal design.

Spike-binding peptides fused to Fc domains are potent entry inhibitors

A series of computationally designed peptides have been described that bind to different regions of the surface of the Spike RBD surrounding the ACE2-binding site and which inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection of Vero E6 cells (45). From these, we selected peptides LCB1 and LCB3, which were especially potent and inhibited infection by the Wuhan variant at picomolar levels. We fused each peptide to an IgG1 Fc domain to create LCB1-Ig and LCB3-Ig fusion constructs which, for simplicity, we re-name here as Spike-binding peptide 1 (SBP1)-Ig and SBP2-Ig. A similar LCB1-Fc construct has previously been described (46), which protected human ACE2 transgenic mice from infection by the Wuhan strain of SARS-CoV-2, if given as an IP injection of 250 µg, either 1 day pre- or 1 day post-exposure.

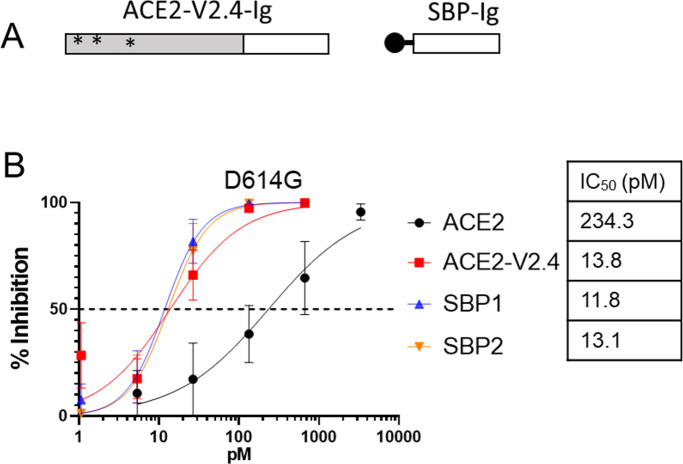

We compared the efficiency of each of the two SBP-Ig constructs against both the original and binding-enhanced ACE2-Ig constructs, using the D614G Spike pseudovirus neutralization assay. Here, we observed that both of the SBP-Ig constructs had similar potency as the enhanced ACE2-V2.4-Ig construct, with a 12–14 picomolar range (Fig. 2). As controls we included Fc fusions of domains that target the HIV-1 envelope protein, eCD4-Ig (14), and J3 (55) and confirmed that neither of these constructs bound to Spike expressing cells nor inhibited the D614G Spike VSV pseudoviruses in neutralization assays (Fig. S2).

Fig 2.

Spike-binding peptides attached to IgG1 Fc domain inhibit D614G pseudovirus. (A) Schematic of SBP-Ig and ACE2-V2.4-Ig constructs. (B) Neutralization assay for VSV pseudovirus containing the D614G Spike variant. Error bars are SEM from n = 4 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves are shown in Table S1.

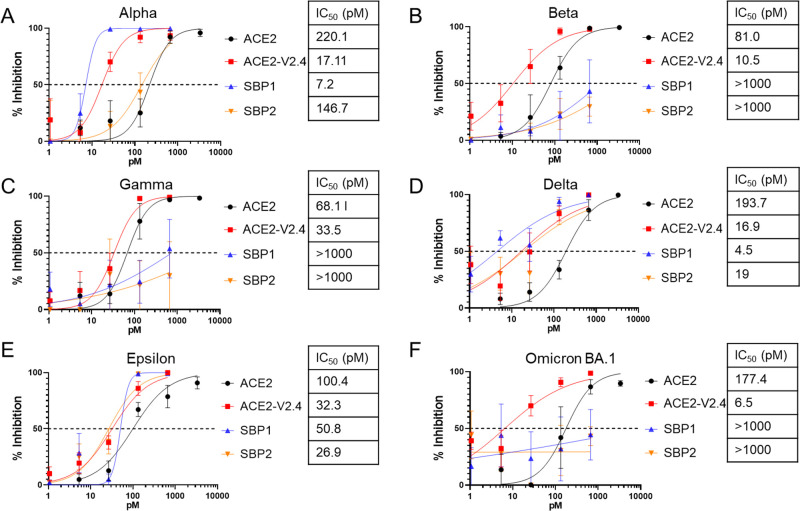

Neutralization of Spike proteins from major SARS-CoV-2 variants

We next compared the panel of ACE2-Ig- and SBP-Ig-based entry inhibitors against VSV pseudoviruses containing Spike proteins from six major SARS-CoV-2 variants: Alpha, Beta, Epsilon, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron BA.1 (Fig. 3). Plasmids were constructed to express Spike proteins containing the specific mutations reported by the CDC for each variant and used to make each specific Spike VSV pseudovirus stock. We found that ACE2-V2.4-Ig potently inhibited all six Spike variants, with an IC50 range of 6.5–33.5 pM and was always significantly more effective than the unmodified ACE2-Ig construct. In contrast, the two SBP-Ig constructs showed differences in their ability to neutralize different Spike variants. Although both inhibited the Alpha, Delta, and Epsilon Spikes, with SBP1-Ig being the most potent, neither SBP-Ig had activity against the Beta, Gamma, or Omicron BA.1 Spikes at the tested concentrations (Fig. 3). This is consistent with observations that RBDs containing mutations characteristic of the Beta, Gamma, and Omicron BA.1 Spikes (K417N, E484K, and N501Y) increased dissociation rates of the LCB1 peptide bound to the RBD by over 100-fold (47).

Fig 3.

Inhibition of entry mediated by different SARS-CoV-2 variants. Neutralization assays were performed with VSV pseudoviruses containing Spike proteins from the indicated SARS-CoV-2 variants: Alpha (A), Beta (B), Gamma (C), Delta (D), Epsilon (E), and Omicron BA.1 (F). In each case, pseudovirus entry was measured in the presence of the indicated inhibitors and doses. Error bars are SEM from n = 4 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves are shown in Table S1.

Spike protein residues K417 and N501 contribute to SBP-Ig resistance

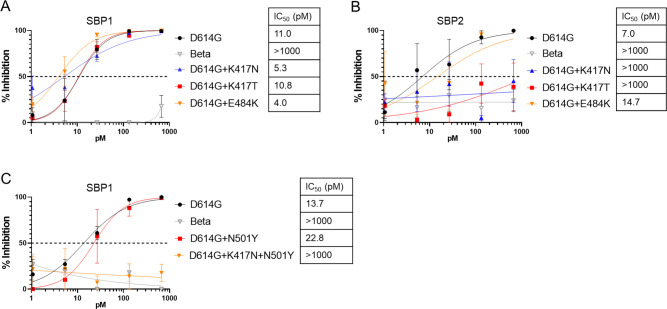

The lack of ability of the two SBP-Ig constructs to inhibit the Beta, Gamma, or Omicron BA.1 pseudoviruses at the concentrations tested corresponds with the ability of these variants to also resist neutralization by antibodies in vaccinated individuals (6 - 8). Sequence alignments of RBDs reveal mutations that are conserved within the resistant variants but are not present in the susceptible variants we tested, specifically residues 417, 484, and 501 (Fig. S3). These residues have also been implicated in monoclonal antibody escape (7). In addition, crystal structures of the two SBPs, complexed with the Wuhan Spike protein (45), show that residues K417, E484, and N501 are within the SBP-binding pocket (Fig. S4).

We, therefore, introduced mutations at these residues into the D614G variant and analyzed the effect on Spike pseudovirus neutralization by the SBP-Ig constructs. This revealed that the K417N or K417T substitutions alone were sufficient to confer resistance against SBP2-Ig. In contrast, resistance to SBP1-Ig required the double substitution of K417N and N501Y, with neither single mutation alone being sufficient (Fig. 4). This agrees with previous pseudovirus studies using a modified truncated LCB-1 peptide, which implicated both mutations K417N and N501Y in Spike resistance (56).

Fig 4.

Importance of K417N/T and N501Y mutations in SBP-Ig resistance. Neutralization assays for VSV pseudoviruses containing indicated Spike proteins. D614G was used as a positive (sensitive) control and Beta variant B.1.351 as a negative (resistant) control. Single point mutations K417N, K417T, or E484K were introduced into D614G Spike and tested for sensitivity to (A) SBP1-Ig and (B) SBP2-Ig. (C) Point mutations N501Y and K417N + N501Y were introduced into D614G Spike and tested against SBP1-Ig. Error bars are SEM from n = 3 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves are shown in Table S1.

Tandem repeats of SBP-1 overcome resistance by the Beta, Gamma, and Omicron BA.1 and BA.5 Spike proteins

Multiplexing SBPs as linked trimeric peptide chains, or by fusing the peptides to trimerization domains, was reported to enhance both Spike-binding affinity and avidity (47). In addition, some multimers overcame the resistance exhibited by Beta and Gamma variants against single copies of the peptides (47). We, therefore, examined the function of multiplexed SBPs in the context of the Fc fusion design, creating tandem duplications of the individual SBP1 and SBP2 reagents, as well as mixed combinations (Fig. 5A). Because Fc domains naturally dimerize, these constructs are expected to present tetramers of the peptides. In an initial test against the sensitive D614G and Delta variants, we observed minimal to no effects of adding a second peptide (Fig. 5B and C), indicating that these designs are well tolerated. For example, both SBP1-Ig and its duplicated version, SBP1-1-Ig, had similar IC50 values and remained the most potent constructs against these variants.

Fig 5.

Effects of tandem combinations of SBP1 and SBP2 on neutralization of Spike variants. (A) Schematic of various SBP-Ig constructs. (B–G) Neutralization assays were performed against VSV pseudoviruses containing the indicated Spike proteins and treated with the indicated entry inhibitors and doses. Error bars are SEM from n = 3 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves are shown in Table S1.

We next tested the tandem repeat constructs against the SBP-resistant variants Beta, Gamma, and the Omicron subvariants BA.1 and BA.5 (Fig. 5D to G). Here, we found that a duplication of SBP1, but not SBP2, could overcome the resistance in these Spike proteins. Moreover, SBP1-1-Ig was observed to be a significantly more potent construct than ACE2-V2.4-Ig, having activity in the range of 1.0–3.5 pM. Finally, for the mixed SBP1 and 2 combinations, we also observed significantly increased activity against the Beta and Gamma Spikes, with SBP1 at the N-terminus being the more potent design. These results demonstrate the ability of multiplexed peptide designs in the context of Fc fusions to enhance the potency of peptide-based inhibitors, suggesting a way to limit future evolution of viral resistance.

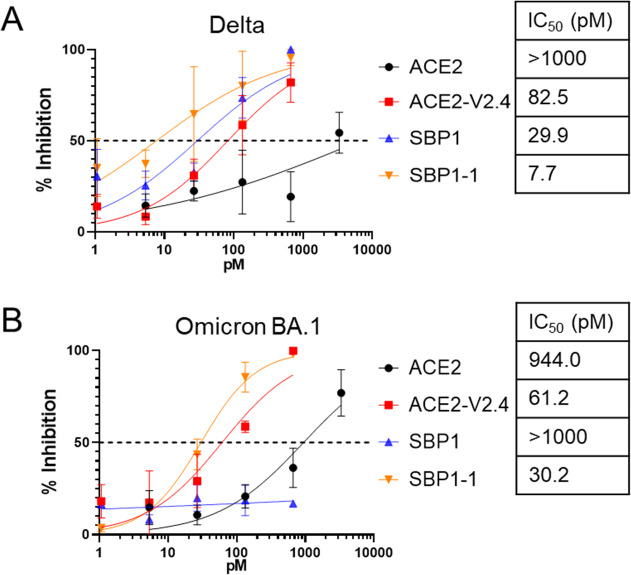

Effect of entry inhibitors on replication of Delta and Omicron BA.1 virus

We next assessed whether the pseudovirus assays were predictive of the activity of the entry inhibitors against replication-competent Delta or Omicron BA.1 virus. These variants were selected as examples of viruses that all (Delta), or only some (BA.1), of the inhibitors were active against. Using a virus-induced cell toxicity assay, we found good correlation with the pseudovirus assays: ACE2-V2.4-Ig and the tandem peptide duplication SBP1-1-Ig inhibited both variants, while the monomeric SBP1-Ig was not effective against Omicron BA.1 (Fig. 6). While the absolute IC50 values differed between the live virus and pseudovirus tests, likely due to the use of assays with different cell lines and readouts (infection vs toxicity), we observed similar trends between inhibitors in both systems. These results, therefore, confirm the usefulness of the pseudovirus system as a model to test SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors.

Fig 6.

Inhibition of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2. VeroE6-hACE2 cells were infected with 0.1 MOI of (A) Delta or (B) Omicron BA.1 SARS-CoV-2 virus, in the presence of various doses of the indicated inhibitors. After 2–3 days, cell viability was measured using an ATP luciferase assay to determine virus-induced cytotoxicity. Percent inhibition of virus replication was determined by comparing values normalized between infected and untreated control cells (0% inhibition value) and uninfected control cells (equivalent to 100% inhibition). Error bars are SEM from n = 3 independent experiments, and mean IC50 values are indicated. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves are shown in Table S1.

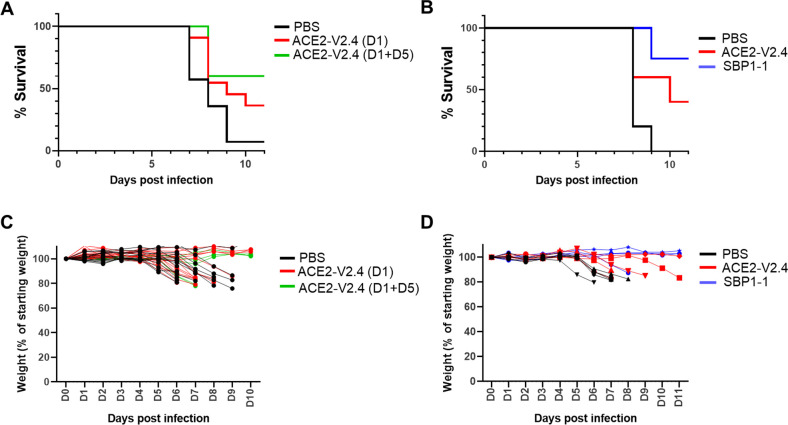

Evaluation of entry inhibitors in Delta variant challenge of ACE2 transgenic mice

The most potent and broad inhibitors we identified in our in vitro neutralization studies were ACE2-V2.4-Ig and SBP1-1-Ig. We, therefore, next compared their ability to protect human ACE2 transgenic mice (57) from the health consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. As a rigorous test, we selected to use the Delta variant since this causes rapid weight loss and death in infected animals. The Omicron BA.1 variant, which in 2022 was the major variant in circulation, was found to be much less pathogenic in this model (data not shown), in agreement with other reports (58).

We first evaluated ACE2-V2.4-Ig. Mice were inoculated intranasally with 1 × 103 PFU of the Delta variant, followed by a single intraperitoneal injection of 10 µg of ACE2-V2.4-Ig 1 day later. In some mice, a second dose was also given at day 5. Mice were observed daily and euthanized if showing significant health deterioration, including losing more than 20% of body weight. This is a low dosing regimen compared to previous publications using ACE2-V2.4 or ACE2-microbodies in mice (28, 32). It was selected to be a challenging regimen, providing incomplete protection, that could allow us to make comparisons about the efficacy of the different inhibitors. For the single dose group, we observed partial protection, with 38% of mice surviving compared to only 5% in the control group (Fig. 7A). The group receiving a second dose showed a higher survival rate of 60%.

Fig 7.

Protection of transgenic human ACE2 mice from SARS-CoV-2 Delta. Mice were infected intranasally with 103 PFU of Delta variant and monitored daily for weight. Mice were euthanized if more than 20% body weight was lost, or health deteriorated. (A) Mice were injected IP with 10 µg ACE2-V2.4-Ig, at either 1 day (n = 16) or 1 plus 5 days (n = 5) post-infection, or were injected with PBS controls (n = 14). (B) Mice were injected IP at 12 h post-infection with 20 µg ACE2-V2.4-Ig (n = 5) or the molar equivalent for SBP1-1-Ig (7.9 µg) (n = 4), or a PBS control (n = 5). (C and D) Weights of individual mice over time from experiments (A and B).

We then compared ACE2-V2.4-Ig to the tandem repeat construct SPB1-1-Ig, which had the most potent activity against all of the variants tested in vitro, including Delta (Fig. 5C and 6). For this experiment, mice were given either a single dose of 20 µg of ACE2-V2.4-Ig or the molar equivalent dose of SBP1-1-Ig (7.9 µg), 12 h post-infection. In this regimen, ACE2-V2.4-Ig allowed 40% of the mice to survive, while SBP1-1-Ig was even more effective, with 75% of the mice surviving after this single dose (Fig. 7B). In all cases, changes in the weight of individual animals showed the same pattern as the survival plots (Fig. 7C and D).

DISCUSSION

There is an urgent need for both therapeutic and preventative treatments for COVID-19, to protect against both current and future variants of SARS-CoV-2 that could evolve. This need is illustrated especially by recent members of the Omicron lineage, which demonstrate resistance to current monoclonal therapies (9 - 12). Toward that goal, entry inhibitors based on, or mimicking, how the ACE2 receptor is recognized by the viral Spike protein are expected to provide a large barrier to viral resistance. Indeed, ACE2-Ig has already been shown to be more resistant to the mutations found in Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Epsilon variants when compared to monoclonal antibodies (59).

In this study, we directly compared two alternative approaches to entry inhibitors. We used a modified ACE2 domain comprising residues 1–740 and mutations (V2.4) that enhance binding to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (28), and two potent engineered small Spike-binding peptides (45). We displayed each inhibitor as a fusion to the IgG1 Fc domain, in a strategy that creates bivalency and is hypothesized to both enhance protein stability and support antibody effector functions that could also clear infected cells. Using a neutralization assay based on Spike VSV pseudoviruses, we found that each of these inhibitors was active at low picomolar concentrations.

ACE2-V2.4-Ig proved to be the most broadly inhibitory molecule we tested, neutralizing all of our panel of SARS-CoV-2 Spike variants with similar efficacy (6.5–33 pM). In contrast, the two SBP-Ig constructs exhibited a narrower range, being susceptible to mutations found in the Spike proteins from Beta, Gamma, and Omicron BA.1, and specifically K417N and N501Y. However, this resistance could be overcome by using tandem combinations of two Spike-binding peptides, where at least the N-terminus peptide was SBP1.

Notably, the most effective antibody therapies are reported to have IC50 values in the range of 6–7 pM against Spike pseudoviruses (12). We found that ACE2-V2.4-Ig was effective in a similar range (6.5–33 pM) and against all major variants. A recent report suggests that the RBD domain of XBB.1.5, a current dominant variant, has much stronger ACE2-binding affinity than previous variants (60), suggesting that ACE2-V2.4-Ig would remain effective against this new variant as well. Similarly, we found that the multiplexed SBP1-1-Ig construct was even more potent, neutralizing various tested pseudoviruses in the range of 1.0–3.5 pM, and being effective against the Omicron BA.5 variant (3.5pM), for which no current antibodies work. This shows that both inhibitor designs hold promise as potent and broad virus neutralizing reagents.

We also compared the abilities of ACE2-V2.4-Ig and SBP1-1-Ig to protect human ACE2 transgenic mice against challenge with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. In this model, we found Delta to be aggressive, causing severe weight loss or death in untreated animals by 7–9 days. To evaluate each construct, we used lower doses than typically given in similar studies but still found that ACE2-V2.4-Ig protected about 40% of mice from death following a single IP dose of 10–20 μg, given 1 day post-infection. For SBP1-1-Ig, 75% of mice were protected following a single IP dose of 7.9 µg (the molar equivalent of 20 µg of ACE2-V2.4-Ig), also given 1 day post-infection.

Our mouse challenge studies agree with and extend previous studies using ACE2 derivatives, although we achieved protection using much lower doses. For example, a study using an alternate ACE2-Ig, containing different binding enhancing mutations (MDR504 hACE2-Fc), was given to Ad5-ACE2 transduced mice at a dose of 360 µg, 4 h before challenge with the original Wuhan virus, then followed for 3 days before necropsy, or for 7 days to monitor survival (22). The authors saw a decrease in viral load and complete survival through the 7 days of the study, although this was a short timeframe to measure survival since even untreated animals had almost 50% survival at that point. Another study gave mice daily injections of ACE2-V2.4-Ig, at a dose of 10–15 mg/kg per day (roughly 200–300 μg/day) for up to 14 days post-infection. This study reported 50% survival for mice infected with the Wuhan variant when the series of injections were started 12–24 h post-infection and 50% survival for mice infected with the Gamma (P.1) variant when ACE2-V2.4-Ig was started 12 h post-infection (44). In contrast, our data indicate that mice can be protected to a similar extent against the Delta variant using a 20–30-fold lower dose of ACE2-V2.4-Ig and only one or two injections.

Several studies have also examined the ability of the LCB1 and LCB3 peptides, and derivatives, to protect mice from SARS-CoV-2 challenges. Using LCB1-Fc, which is equivalent to our SBP1-Ig, 100% of ACE2 transgenic mice survived challenge by the Wuhan virus, if 250 µg of LCB1-Fc was given as IP injections 1 day pre- or 1 day post-exposure (46). These doses are 25-fold higher than the dose we used here to study the effects of the tandem SBP1-1-Ig construct.

Our studies revealed the significant increase in potency and breadth achieved by linking two copies of the SBPs in the context of an Fc fusion, with SBP1-1-Ig being the most potent design we analyzed. Similarly, multimeric SBP constructs based on homotrimeric versions of another peptide, AHB2, proved to be highly effective in mice when given intranasally as a 50 µg dose, 1 day pre-infection with either Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variants, or 1 day post-infection with Beta or Delta (47). Using this regimen, mice showed reduced weight loss and lower tissue viral loads by 6–7 days post-infection, although the mice were not monitored long enough to look at effects on survival. In comparison, our SBP1-1-Ig construct protected 75% of animals from death over 11 days following only a single dose of 7.9 µg, given IP at 12 h post-infection with the Delta variant. One caveat to our study is that we did not measure viral loads in tissues of the animals, which would have provided additional information about the treatment.

Despite the potential promise of these broad and potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2, several safety concerns will need to be addressed. An important consideration for the ACE2 derivatives is the use of a molecule involved in blood pressure regulation. Although recombinant ACE2 is already being evaluated in clinical trials as a treatment for both acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID , some of these concerns may be further lessened by the inclusion of the mutations that inactivate the protein’s catalytic activity (18), in the ACE2-V2.4 design. In addition, the presence of an Fc domain in all of our constructs brings potential advantages, such as extending the half-life of the molecules, allowing dimeric presentations of inhibitors, and the possibility of clearing infected cells through antibody-mediated mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), although this would need to be experimentally demonstrated. However, it is also conceivable that enhancement of such immune activities could have unintended consequences in severely ill individuals, in which case we note that Fc mutations that abrogate ADCC activity still retain the ability to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and in mice (22).

Development of resistance of the virus to these entry inhibitors is also a concern. In particular, it is possible that ACE2-based inhibitors could be thwarted by the use of an alternate receptor such as CD147, although the mechanisms involved in these alternate pathways are still unclear (61). Some evidence suggests that CD147 interacts with the Spike protein at a similar domain as ACE2 (62) and so may also be susceptible to ACE2-based inhibitors. However, further investigations are needed to have a better understanding of the role of alternate receptors and the effects of ACE2-derived inhibitors on their actions. Encouragingly, preliminary studies have failed to observe resistance mutations arising against the enhanced ACE2-V2.4-Ig (20, 33), although similar studies will also need to be done for the SBP1-1-Ig design.

Another important consideration for any therapy will be the mode of delivery. In addition to infusion, as is commonly done for antibody therapies, these inhibitors also have the potential to be delivered using a nebulized inhalation strategy. Such an approach could be both simpler to administer and have the advantage of delivering inhibitors from the nasal cavity to the lungs. The small trimeric SBP peptides described by Hunt et.al. (47) were compatible with nebulization in mice, and ACE2-V2.4-IgG1 was also recently delivered through inhalation in mice (41).

In summary, we have shown that ACE2-V2.4-Ig is a broad inhibitor of all current variants of SARS-CoV-2 and would likely be a good candidate as an alternative therapy to antibodies in the future as the virus continues to mutate. Multiplexed SBP constructs, such as SBP1-1-Ig, also hold promise as effective therapies since the multiplexed design overcame current circulating mutations that led to resistance against the monomers. However, the pattern of evolution of SARS-CoV-2 warrants that all such therapeutics will need to be monitored for effectiveness as new viral variants arise.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and cell lines

ACE2-Ig comprises the extracellular domain of human ACE2 (amino acids 1–740), which was amplified by PCR from human cDNA using primers forward (5′-CAGTGTGGTGGAATTCACCATGTCAAGCTCTTCCTGGCT-3′) and reverse (5′-CACAAGATTTGGGCTCGGAAACAGGGGGCTGGTTAG-3′) and cloned into plasmid pVAX-IGHG1ΔCH1 by In-Fusion cloning (Takara Bio, San Jose, CA, USA). This plasmid contains an Fc domain comprising Kabat numbers 226–478 of human IgG1. The V2.4 mutations (T27Y, L79T, and N330Y) (28) were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis to create ACE2-v2.4-Ig. For SBP1-Ig and SBP2-Ig, gBlocks (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA, USA) comprising the sequences of LCB1 and LCB3, respectively (45), were similarly inserted into pVAX with a (G4S)3 linker separating the peptide and IgG1 Fc domain. For SBP-Ig tandem repeat constructs, additional copies of peptide sequences were inserted, separated by (G4S)3 linkers. Control Fc fusions were eCD4-Ig (14) and a fusion with the J3 nanobody (55).

An expression plasmid for the Spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 isolate (GenBank accession no. MN908947.3) in a pcDNA3.3 backbone was provided by James Voss (The Scripps Research Institute). Different variants of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike proteins were synthesized by PCR mutagenesis (variant D614G) or synthesized as gBlocks and cloned into the same expression plasmid. The variants contained specific Spike mutations as reported by the CDC variants tracker (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-classifications.html): Alpha-B.1.1.7, Beta-B1.351, Gamma-P.1, Delta-B.1.617.2, Epsilon-Cal20.C, Omicron-B.1.537 (BA.1), or Omicron-BA.5.

293T cells were obtained from ATCC. HeLa-ACE2 cells (54) were generously provided by James Voss. All cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bio, West Sacramento, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). VeroE6 cells overexpressing ACE2 (VeroE6-hACE2) were obtained from Dr. Jae Jung and maintained in DMEM high glucose, supplemented with 10% FBS, 2.5 µg/mL puromycin.

Virus stocks

SARS-CoV-2 stocks were obtained from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Delta isolate (B.1.617.2) USA/PH-C658/2021, NR-55611 and Omicron BA.1 isolate (B.1.1.529) USA/HP-20874/2021, NR-56461. Virus was propagated on Vero E6-ACE2 cells as described (63) and stored at −80°C.

Production of entry inhibitors

Entry inhibitors or control constructs were generated by calcium phosphate transient transfection of 293T cells, using 7 µg/well plasmid DNA in 6-well plates. After 4 h, media was changed, and supernatants collected after a further 48 h incubation at 37°C. Inhibitors were also purchased as custom protein preparations (ProMab Biotechnologies, Inc., Richmond, CA). Inhibitor concentrations were determined by IgG ELISA. Briefly, goat anti-human IgG-Fc (SoutherDeatil added that was ommitted in original manuscriptn Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) was coated onto 96-well plates overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) then blocked with 5% milk for 4 h at 4°C. Serial dilutions of inhibitor supernatants were added and incubated at 4°C overnight, with recombinant human IgG1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) used as a standard. Plates were washed three times with PBST, mouse-anti-human IgG Fc-HRP (Southern Biotech) was diluted 1:2,000 in blocking buffer and added, and plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Plates were washed three times with PBST and SigmaFAST OPD (Sigma) added. Plates were read with a Mithras LB940 plate reader (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wilbad, Germany) to calculate sample concentration.

SARS-CoV-2 Spike VSV pseudoviruses and neutralization assays

Replication-deficient VSVΔG vectors (64), containing an expression cassette for firefly luciferase and pseudotyped with various SARS-CoV-2 Spike proteins, were generated by transfection of 293T cells, followed by concentration by ultracentrifugation or tangential flow filtration, as previously described (53). The Spike pseudovirus stocks were titered by serial dilution on HeLA-ACE2 cells, with luciferase activity measured on a Mithras LB940 plate reader, as described (53), and calculated as relative light units (RLU).

For neutralization assays, 1 × 104 HeLa-ACE2 cells/well were plated in 96-well half-area white plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and cultured overnight at 37°C. Spike pseudovirus stocks, calculated to produce approximately 100,000 RLU, were incubated alone or with different concentrations of inhibitors or control constructs for 1 h at 37°C before being added to the cells, in triplicate. The following day, media was removed and replaced with 50 µL DMEM without phenol red and 25 µL of Britelite plus (Perkin Elmer, Richmond, CA, USA), and luciferase activity was measured following the manufacturer’s protocol. Plates were read and RLU calculated using a Mithras LB940 plate reader. Best fit variable slope curves and IC50 calculations were calculated using PRISM software. P-values comparing the IC50 between different inhibitor curves were also calculated with PRISM.

Spike-binding assay

293T cells in 6-well plates were transiently transfected with 3 µg/well of D614G Spike plasmid DNA using calcium phosphate transfection. After 4 h, media was changed, and 48 h later, untransfected or Spike transfected cells were scraped and pipetted to mechanically break into single cells. Cells were then incubated with 1 µM of indicated inhibitor or control Fc constructs at 4°C for 30 min, washed 3× with cold PBS, and then incubated with anti-human IgG conjugated to PE (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) diluted 1:400 in PBS for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed again and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and binding of Fc constructs was determined by flow cytometry on a FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences). To measure Spike expression, cells were separately immunostained with anti-Spike S1 antibody at 1:100 dilution in PBS (Prosci, Fort Collins, CO, USA), followed by goat anti-rabbit alexafluor 647 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted 1:400 in PBS. Spike expression was measured by flow cytometry.

SARS-CoV-2 cytopathic effect assays and evaluation of inhibitors

Work with replication-competent virus was carried out in The Hastings Foundation and The Wright Foundation Laboratories BSL3 facility at USC. Briefly, 1 × 104 VeroE6-hACE2 cells/well in DMEM-10 were seeded in a black walled 96-well plate and incubated overnight. Virus (Delta or Omicron BA.1) at 0.1 MOI in 100 µL volume of DMEM-10 was incubated with the indicated amount of inhibitor for 1 h at 37°C, then added to the cells and incubated for another 1 h. The virus/inhibitor mixture was removed and replaced with 100 µL fresh media, and plates incubated for 2 or 3 days, until visual confirmation of cytopathic effects in infected/untreated control wells. Cell toxicity was quantified using the Promega Viral Tox Glo (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) which measures ATP using a luciferase readout, per the manufacturer’s instructions, with luciferase levels read on a Molecular Devices FilterMax F5 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Percentage inhibition was calculated by using the values from infected but untreated control samples as corresponding to 0% inhibition, and the values from uninfected control cells as corresponding to 100% inhibition using the formula: (sample value − virus-infected control value)/(Uninfected control value − virus-infected control value) × 100.

Mouse infections and treatment with inhibitors

This work was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, protocol 21337. Heterozygous K18-hACE2 C57BL/6 J mice (57) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA; cat. no. 034860) and transferred and housed within ABSL3 containment upon receipt. Female mice 9–10 weeks old were challenged through intranasal inoculation with 1 × 103 PFU SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant (clinical isolate USA/PHC658/2021, NR-55611) in 30 µL PBS, by intranasal injection. Control mice received PBS alone. Mice were additionally treated with inhibitors at indicated times and doses, by intraperitoneal injection. Mice were monitored and weighed daily and euthanized due to declining health, including but not limited to 20% wt loss or failure of objective reflex tests. All animal care and experiments were performed according to the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Southern California.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant to P.M.C. from a gift by the W.M. Keck Foundation to support COVID-19 research at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. Work with SARS-CoV-2 was performed in the Biosafety Level 3 Facility within The Hastings Foundation and The Wright Foundation Laboratories at the Keck School of Medicine and supported by a grant from the COVID-19 Keck Research Fund.

Contributor Information

Paula M. Cannon, Email: pcannon@usc.edu.

Mark T. Heise, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00684-23.

Supplemental figures S1 to S4 and Table S1.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si H-R, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang C-L, Chen H-D, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang R-D, Liu M-Q, Chen Y, Shen X-R, Wang X, Zheng X-S, Zhao K, Chen Q-J, Deng F, Liu L-L, Yan B, Zhan F-X, Wang Y-Y, Xiao G-F, Shi Z-L. 2020. Addendum: a pneumonia outbreak associated with a new Coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 588:E6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. Baltimore MD. [Google Scholar]

- 3. CDC COVID data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions.

- 4. Hogan MJ, Pardi N. 2022. mRNA vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Annu Rev Med 73:17–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042420-112725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang Y-C, Lu R-M, Su S-C, Chiang P-Y, Ko S-H, Ke F-Y, Liang K-H, Hsieh T-Y, Wu H-C. 2022. Monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 therapy and SARS-CoV-2 detection. J Biomed Sci 29:1. doi: 10.1186/s12929-021-00784-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoffmann M, Arora P, Groß R, Seidel A, Hörnich BF, Hahn AS, Krüger N, Graichen L, Hofmann-Winkler H, Kempf A, Winkler MS, Schulz S, Jäck H-M, Jahrsdörfer B, Schrezenmeier H, Müller M, Kleger A, Münch J, Pöhlmann S. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and P.1 escape from neutralizing antibodies. Cell 184:2384–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou D, Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Liu C, Mentzer AJ, Ginn HM, Zhao Y, Duyvesteyn HME, Tuekprakhon A, Nutalai R, Wang B, Paesen GC, Lopez-Camacho C, Slon-Campos J, Hallis B, Coombes N, Bewley K, Charlton S, Walter TS, Skelly D, Lumley SF, Dold C, Levin R, Dong T, Pollard AJ, Knight JC, Crook D, Lambe T, Clutterbuck E, Bibi S, Flaxman A, Bittaye M, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Gilbert S, James W, Carroll MW, Klenerman P, Barnes E, Dunachie SJ, Fry EE, Mongkolsapaya J, Ren J, Stuart DI, Screaton GR. 2021. Evidence of escape of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.351 from natural and vaccine-induced sera. Cell 184:2348–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yao L, Zhu KL, Jiang XL, Wang XJ, Zhan BD, Gao HX, Geng XY, Duan LJ, Dai EH, Ma MJ. 2022. Omicron subvariants escape antibodies elicited by vaccination and BA.2.2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis 22:1116–1117. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00410-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uraki R, Ito M, Kiso M, Yamayoshi S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Furusawa Y, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Imai M, Koga M, Yamamoto S, Adachi E, Saito M, Tsutsumi T, Otani A, Kikuchi T, Yotsuyanagi H, Halfmann PJ, Pekosz A, Kawaoka Y. 2023. Antiviral and bivalent vaccine efficacy against an Omicron XBB.1.5 isolate. Lancet Infect Dis 23:402–403. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00070-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tada T, Zhou H, Dcosta BM, Samanovic MI, Chivukula V, Herati RS, Hubbard SR, Mulligan MJ, Landau NR. 2022. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant to neutralization by vaccine-elicited and therapeutic antibodies. eBioMedicine 78:103944. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arora P, Kempf A, Nehlmeier I, Schulz SR, Jäck H-M, Pöhlmann S, Hoffmann M. 2023. Omicron sublineage BQ.1.1 resistance to monoclonal antibodies. Lancet Infect Dis 23:22–23. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00733-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cao Y, Wang J, Jian F, Xiao T, Song W, Yisimayi A, Huang W, Li Q, Wang P, An R, Wang J, Wang Y, Niu X, Yang S, Liang H, Sun H, Li T, Yu Y, Cui Q, Liu S, Yang X, Du S, Zhang Z, Hao X, Shao F, Jin R, Wang X, Xiao J, Wang Y, Xie XS. 2022. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 602:657–663. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04385-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chitsike L, Duerksen-Hughes P. 2021. Keep out! SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors: their role and utility as COVID-19 therapeutics. Virol J 18:154. doi: 10.1186/s12985-021-01624-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gardner MR, Kattenhorn LM, Kondur HR, von Schaewen M, Dorfman T, Chiang JJ, Haworth KG, Decker JM, Alpert MD, Bailey CC, Neale ES Jr, Fellinger CH, Joshi VR, Fuchs SP, Martinez-Navio JM, Quinlan BD, Yao AY, Mouquet H, Gorman J, Zhang B, Poignard P, Nussenzweig MC, Burton DR, Kwong PD, Piatak M Jr, Lifson JD, Gao G, Desrosiers RC, Evans DT, Hahn BH, Ploss A, Cannon PM, Seaman MS, Farzan M. 2015. AAV-expressed eCD4-Ig provides durable protection from multiple SHIV challenges. Nature 519:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature14264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fellinger CH, Gardner MR, Weber JA, Alfant B, Zhou AS, Farzan M. 2019. eCD4-Ig limits HIV-1 escape more effectively than CD4-Ig or a broadly neutralizing antibody. J Virol 93:e00443-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00443-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lei C, Qian K, Li T, Zhang S, Fu W, Ding M, Hu S. 2020. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat Commun 11:2070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16048-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li Y, Wang H, Tang X, Fang S, Ma D, Du C, Wang Y, Pan H, Yao W, Zhang R, Zou X, Zheng J, Xu L, Farzan M, Zhong G, Gallagher T. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 and three related Coronaviruses utilize multiple ACE2 orthologs and are potently blocked by an improved ACE2-Ig. J Virol 94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01283-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moore MJ, Dorfman T, Li W, Wong SK, Li Y, Kuhn JH, Coderre J, Vasilieva N, Han Z, Greenough TC, Farzan M, Choe H. 2004. Retroviruses pseudotyped with the severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus spike protein efficiently infect cells expressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J Virol 78:10628–10635. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10628-10635.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hofmann H, Geier M, Marzi A, Krumbiegel M, Peipp M, Fey GH, Gramberg T, Pöhlmann S. 2004. Susceptibility to SARS Coronavirus S protein-driven infection correlates with expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 And infection can be blocked by soluble receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 319:1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higuchi Y, Suzuki T, Arimori T, Ikemura N, Mihara E, Kirita Y, Ohgitani E, Mazda O, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Sakai Y, Itoh Y, Sugihara F, Matsuura Y, Matoba S, Okamoto T, Takagi J, Hoshino A. 2021. Engineered ACE2 receptor therapy overcomes mutational escape of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24013-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glasgow A, Glasgow J, Limonta D, Solomon P, Lui I, Zhang Y, Nix MA, Rettko NJ, Zha S, Yamin R, Kao K, Rosenberg OS, Ravetch JV, Wiita AP, Leung KK, Lim SA, Zhou XX, Hobman TC, Kortemme T, Wells JA. 2020. Engineered ACE2 receptor traps potently neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:28046–28055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016093117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwanaga N, Cooper L, Rong L, Maness NJ, Beddingfield B, Qin Z, Crabtree J, Tripp RA, Yang H, Blair R, Jangra S, García-Sastre A, Schotsaert M, Chandra S, Robinson JE, Srivastava A, Rabito F, Qin X, Kolls JK. 2022. ACE2-IgG1 Fusions with improved in vitro and in vivo activity against SARS-CoV-2. iScience 25:103670. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Z, Zeng E, Zhang L, Wang W, Jin Y, Sun J, Huang S, Yin W, Dai J, Zhuang Z, Chen Z, Sun J, Zhu A, Li F, Cao W, Li X, Shi Y, Gan M, Zhang S, Wei P, Huang J, Zhong N, Zhong G, Zhao J, Wang Y, Shao W, Zhao J. 2021. Potent prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of recombinant human Ace2-FC against SARS-Cov-2 infection in vivo. Cell Discov 7:65. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00302-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Y, Sun L, Ullah I, Beaudoin-Bussières G, Anand SP, Hederman AP, Tolbert WD, Sherburn R, Nguyen DN, Marchitto L, Ding S, Wu D, Luo Y, Gottumukkala S, Moran S, Kumar P, Piszczek G, Mothes W, Ackerman ME, Finzi A, Uchil PD, Gonzalez FJ, Pazgier M. 2022. Engineered ACE2-Fc counters murine lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection through direct neutralization and Fc-effector activities. Sci Adv 8:eabn4188. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abn4188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang KY, Lin MS, Kuo TC, Chen CL, Lin CC, Chou YC, Chao TL, Pang YH, Kao HC, Huang RS, Lin S, Chang SY, Yang PC. 2021. Humanized COVID‐19 decoy antibody effectively blocks viral entry and prevents SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. EMBO Mol Med 13:e12828. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Svilenov HL, Sacherl J, Reiter A, Wolff LS, Cheng CC, Stern M, Grass V, Feuerherd M, Wachs FP, Simonavicius N, Pippig S, Wolschin F, Keppler OT, Buchner J, Brockmeyer C, Protzer U. 2021. Picomolar inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern by an engineered ACE2-IgG4-Fc fusion protein. Antiviral Res 196:105197. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jing W, Procko E. 2021. ACE2-based decoy receptors for SARS Coronavirus 2. Proteins 89:1065–1078. doi: 10.1002/prot.26140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan KK, Dorosky D, Sharma P, Abbasi SA, Dye JM, Kranz DM, Herbert AS, Procko E. 2020. Engineering human ACE2 to optimize binding to the spike protein of SARS Coronavirus 2. Science 369:1261–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, Hagelkrüys A, Wimmer RA, Stahl M, Leopoldi A, Garreta E, Hurtado Del Pozo C, Prosper F, Romero JP, Wirnsberger G, Zhang H, Slutsky AS, Conder R, Montserrat N, Mirazimi A, Penninger JM. 2020. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell 181:905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ikemura N, Taminishi S, Inaba T, Arimori T, Motooka D, Katoh K, Kirita Y, Higuchi Y, Li S, Suzuki T, Itoh Y, Ozaki Y, Nakamura S, Matoba S, Standley DM, Okamoto T, Takagi J, Hoshino A. 2022. An engineered ACE2 decoy neutralizes the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant and confers protection against infection in vivo. Sci Transl Med 14:eabn7737. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn7737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zoufaly A, Poglitsch M, Aberle JH, Hoepler W, Seitz T, Traugott M, Grieb A, Pawelka E, Laferl H, Wenisch C, Neuhold S, Haider D, Stiasny K, Bergthaler A, Puchhammer-Stoeckl E, Mirazimi A, Montserrat N, Zhang H, Slutsky AS, Penninger JM. 2020. Human recombinant soluble ACE2 in severe COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med 8:1154–1158. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30418-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tada T, Fan C, Chen JS, Kaur R, Stapleford KA, Gristick H, Dcosta BM, Wilen CB, Nimigean CM, Landau NR. 2020. An ACE2 microbody containing a single immunoglobulin Fc domain is a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep 33:108528. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zekri L, Ruetalo N, Christie M, Walker C, Manz T, Rammensee H-G, Salih HR, Schindler M, Jung G. 2023. Novel ACE2 fusion protein with adapting activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants in vitro. Front Immunol 14:1112505. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1112505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lu M, Yao W, Li Y, Ma D, Zhang Z, Wang H, Tang X, Wang Y, Li C, Cheng D, Lin H, Yin Y, Zhao J, Zhong G. 2023. Broadly effective ACE2 decoy proteins protect mice from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.22.529625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35. Tada T, Dcosta BM, Zhou H, Landau NR. 2023. Prophylaxis and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection by an ACE2 receptor decoy in a preclinical animal model. iScience 26:106092. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Torchia JA, Tavares AH, Carstensen LS, Chen DY, Huang J, Xiao T, Mukherjee S, Reeves PM, Tu H, Sluder AE, Chen B, Kotton DN, Bowen RA, Saeed M, Poznansky MC, Freeman GJ. 2022. Optimized ACE2 decoys neutralize antibody-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants through functional receptor mimicry and treat infection in vivo. Sci Adv 8:eabq6527. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abq6527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsai T-I, Khalili JS, Gilchrist M, Waight AB, Cohen D, Zhuo S, Zhang Y, Ding M, Zhu H, Mak AN-S, Zhu Y, Goulet DR. 2022. ACE2-Fc fusion protein overcomes viral escape by potently neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Antiviral Res 199:105271. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leach A, Ilca FT, Akbar Z, Ferrari M, Bentley EM, Mattiuzzo G, Onuoha S, Miller A, Ali H, Rabbitts TH. 2021. A tetrameric ACE2 protein broadly neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 spike variants of concern with elevated potency. Antiviral Res 194:105147. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ferrari M, Mekkaoui L, Ilca FT, Akbar Z, Bughda R, Lamb K, Ward K, Parekh F, Karattil R, Allen C, Wu P, Baldan V, Mattiuzzo G, Bentley EM, Takeuchi Y, Sillibourne J, Datta P, Kinna A, Pule M, Onuoha SC, Gallagher T. 2021. Characterization of a novel ACE2-based therapeutic with enhanced rather than reduced activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants. J Virol 95. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00685-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanaka S, Nelson G, Olson CA, Buzko O, Higashide W, Shin A, Gonzalez M, Taft J, Patel R, Buta S, Richardson A, Bogunovic D, Spilman P, Niazi K, Rabizadeh S, Soon-Shiong P. 2021. An ACE2 triple decoy that neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 shows enhanced affinity for virus variants. Sci Rep 11:12740. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91809-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang L, Narayanan KK, Cooper L, Chan KK, Skeeters SS, Devlin CA, Aguhob A, Shirley K, Rong L, Rehman J, Malik AB, Procko E. 2022. An ACE2 decoy can be administered by inhalation and potently targets Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. EMBO Mol Med 14:e16109. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202216109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cohen-Dvashi H, Weinstein J, Katz M, Eilon-Ashkenazy M, Mor Y, Shimon A, Achdout H, Tamir H, Israely T, Strobelt R, Shemesh M, Stoler-Barak L, Shulman Z, Paran N, Fleishman SJ, Diskin R. 2022. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoadhesin remains effective against Omicron and other emerging variants of concern. iScience 25:105193. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sims JJ, Greig JA, Michalson KT, Lian S, Martino RA, Meggersee R, Turner KB, Nambiar K, Dyer C, Hinderer C, Horiuchi M, Yan H, Huang X, Chen SJ, Wilson JM. 2021. Intranasal gene therapy to prevent infection by SARS-CoV-2 variants. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009544. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang L, Dutta S, Xiong S, Chan M, Chan KK, Fan TM, Bailey KL, Lindeblad M, Cooper LM, Rong L, Gugliuzza AF, Shukla D, Procko E, Rehman J, Malik AB. 2022. Engineered ACE2 decoy mitigates lung injury and death induced by SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Chem Biol 18:342–351. doi: 10.1038/s41589-021-00965-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cao L, Goreshnik I, Coventry B, Case JB, Miller L, Kozodoy L, Chen RE, Carter L, Walls AC, Park YJ, Strauch EM, Stewart L, Diamond MS, Veesler D, Baker D. 2020. De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors. Science 370:426–431. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Case JB, Chen RE, Cao L, Ying B, Winkler ES, Johnson M, Goreshnik I, Pham MN, Shrihari S, Kafai NM, Bailey AL, Xie X, Shi PY, Ravichandran R, Carter L, Stewart L, Baker D, Diamond MS. 2021. Ultrapotent miniproteins targeting the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain protect against infection and disease. Cell Host Microbe 29:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hunt AC, Case JB, Park Y-J, Cao L, Wu K, Walls AC, Liu Z, Bowen JE, Yeh H-W, Saini S, Helms L, Zhao YT, Hsiang T-Y, Starr TN, Goreshnik I, Kozodoy L, Carter L, Ravichandran R, Green LB, Matochko WL, Thomson CA, Vögeli B, Krüger A, VanBlargan LA, Chen RE, Ying B, Bailey AL, Kafai NM, Boyken SE, Ljubetič A, Edman N, Ueda G, Chow CM, Johnson M, Addetia A, Navarro M-J, Panpradist N, Gale M, Freedman BS, Bloom JD, Ruohola-Baker H, Whelan SPJ, Stewart L, Diamond MS, Veesler D, Jewett MC, Baker D. 2022. Multivalent designed proteins neutralize SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and confer protection against infection in mice. Sci Transl Med 14:eabn1252. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Khatri B, Pramanick I, Malladi SK, Rajmani RS, Kumar S, Ghosh P, Sengupta N, Rahisuddin R, Kumar N, Kumaran S, Ringe RP, Varadarajan R, Dutta S, Chatterjee J. 2022. A dimeric proteomimetic prevents SARS-CoV-2 infection by dimerizing the spike protein. Nat Chem Biol 18:1046–1055. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01060-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang L, Jackson CB, Mou H, Ojha A, Peng H, Quinlan BD, Rangarajan ES, Pan A, Vanderheiden A, Suthar MS, Li W, Izard T, Rader C, Farzan M, Choe H. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat Commun 11:6013. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ozono S, Zhang Y, Ode H, Sano K, Tan TS, Imai K, Miyoshi K, Kishigami S, Ueno T, Iwatani Y, Suzuki T, Tokunaga K. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike mutation increases entry efficiency with enhanced ACE2-binding affinity. Nat Commun 12:848. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21118-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zehender G, Lai A, Bergna A, Meroni L, Riva A, Balotta C, Tarkowski M, Gabrieli A, Bernacchia D, Rusconi S, Rizzardini G, Antinori S, Galli M. 2020. Genomic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. J Med Virol 92:1637–1640. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhu Y, Yu D, Yan H, Chong H, He Y, Pfeiffer JK. 2020. Design of potent membrane fusion inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2, an emerging Coronavirus with high fusogenic activity. J Virol 94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen HY, Huang C, Tian L, Huang X, Zhang C, Llewellyn GN, Rogers GL, Andresen K, O’Gorman MRG, Chen YW, Cannon PM. 2021. Cytoplasmic tail truncation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enhances titer of pseudotyped vectors but masks the effect of the D614G mutation. J Virol 95:e0096621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00966-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rogers TF, Zhao F, Huang D, Beutler N, Burns A, He W, Limbo O, Smith C, Song G, Woehl J, Yang L, Abbott RK, Callaghan S, Garcia E, Hurtado J, Parren M, Peng L, Ramirez S, Ricketts J, Ricciardi MJ, Rawlings SA, Wu NC, Yuan M, Smith DM, Nemazee D, Teijaro JR, Voss JE, Wilson IA, Andrabi R, Briney B, Landais E, Sok D, Jardine JG, Burton DR. 2020. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science 369:956–963. doi: 10.1126/science.abc7520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCoy LE, Quigley AF, Strokappe NM, Bulmer-Thomas B, Seaman MS, Mortier D, Rutten L, Chander N, Edwards CJ, Ketteler R, Davis D, Verrips T, Weiss RA. 2012. Potent and broad neutralization of HIV-1 by a llama antibody elicited by immunization. J Exp Med 209:1091–1103. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weißenborn L, Richel E, Hüseman H, Welzer J, Beck S, Schäfer S, Sticht H, Überla K, Eichler J. 2022. Smaller, stronger, more stable: peptide variants of a SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing miniprotein. Int J Mol Sci 23:6309. doi: 10.3390/ijms23116309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McCray PB, Pewe L, Wohlford-Lenane C, Hickey M, Manzel L, Shi L, Netland J, Jia HP, Halabi C, Sigmund CD, Meyerholz DK, Kirby P, Look DC, Perlman S. 2007. Lethal infection of K18-hACE2 mice infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus. J Virol 81:813–821. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02012-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Natekar JP, Pathak H, Stone S, Kumari P, Sharma S, Auroni TT, Arora K, Rothan HA, Kumar M. 2022. Differential pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in human ACE2-expressing mice. Viruses 14:1139. doi: 10.3390/v14061139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hastie KM, Li H, Bedinger D, Schendel SL, Dennison SM, Li K, Rayaprolu V, Yu X, Mann C, Zandonatti M, Diaz Avalos R, Zyla D, Buck T, Hui S, Shaffer K, Hariharan C, Yin J, Olmedillas E, Enriquez A, Parekh D, Abraha M, Feeney E, Horn GQ, CoVIC-DB team1, Aldon Y, Ali H, Aracic S, Cobb RR, Federman RS, Fernandez JM, Glanville J, Green R, Grigoryan G, Lujan Hernandez AG, Ho DD, Huang K-YA, Ingraham J, Jiang W, Kellam P, Kim C, Kim M, Kim HM, Kong C, Krebs SJ, Lan F, Lang G, Lee S, Leung CL, Liu J, Lu Y, MacCamy A, McGuire AT, Palser AL, Rabbitts TH, Rikhtegaran Tehrani Z, Sajadi MM, Sanders RW, Sato AK, Schweizer L, Seo J, Shen B, Snitselaar JL, Stamatatos L, Tan Y, Tomic MT, van Gils MJ, Youssef S, Yu J, Yuan TZ, Zhang Q, Peters B, Tomaras GD, Germann T, Saphire EO. 2021. Defining variant-resistant epitopes targeted by SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: a global consortium study. Science 374:472–478. doi: 10.1126/science.abh2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yue C, Song W, Wang L, Jian F, Chen X, Gao F, Shen Z, Wang Y, Wang X, Cao Y. 2023. ACE2 binding and antibody evasion in enhanced transmissibility of XBB.1.5. Lancet Infect Dis 23:278–280. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00010-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lim S, Zhang M, Chang TL. 2022. ACE2-independent alternative receptors for SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 14:2535. doi: 10.3390/v14112535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Helal MA, Shouman S, Abdelwaly A, Elmehrath AO, Essawy M, Sayed SM, Saleh AH, El-Badri N. 2022. Molecular basis of the potential interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to CD147 in COVID-19 associated-lymphopenia. J Biomol Struct Dyn 40:1109–1119. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1822208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shin WJ, Ha DP, Machida K, Lee AS. 2022. The stress-inducible ER chaperone GRP78/BiP is upregulated during SARS-CoV-2 infection and acts as a pro-viral protein. Nat Commun 13:6551. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34065-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Whitt MA. 2010. Generation of VSV pseudotypes using recombinant DeltaG-VSV for studies on virus entry, identification of entry inhibitors, and immune responses to vaccines. J Virol Methods 169:365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figures S1 to S4 and Table S1.