History

A 14-year-old girl with a history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and myopia presented emergently at Boston Children’s Hospital with a 5-month history of intermittent headache, palpitations, tachycardia, and diaphoresis. Five weeks prior to presentation, she had a brief flulike illness, with shaking chills, muscle aches, malaise, and fatigue. Birth and family history, as well as the remaining review of systems were noncontributory.

Examination

On presentation, the patient was normotensive. However, prior to transfer to the floor for evaluation of her symptoms, she experienced a hypertensive crisis, with blood pressure reaching 192/144 mm Hg. She was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further workup and blood pressure management, with good response to hydralazine and nifedipine. While in the ICU, an ophthalmologic consultation was requested to evaluate for hypertensive retinopathy.

On examination, her best-corrected visual acuity in each eye was 20/40. Her pupils were equally round and reactive to light, with no relative afferent pupillary defect. Visual fields were full to confrontation, and color vision by Ishihara plates was normal. Extraocular motility was full, and she was orthophoric. The Amsler grid was abnormal, with the patient describing “a big curve” centrally bilaterally. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment was unremarkable. Dilated funduscopic examination revealed clear media but edematous and hyperemic optic discs, with retinal hemorrhages and cotton wool spots along the arcades bilaterally. Hard exudates with macular star configuration were noted in both eyes. The findings were consistent with grade IV hypertensive retinopathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fundus photographs at presentation of the right eye (A) and left eye (B) of a 14-year-old girl showing hard exudates in a macular star configuration (thin arrows) and cotton wool spots (thick arrows) with intraretinal hemorrhages and optic disc edema.

Ancillary Testing

The episode of hypertensive crisis, in conjunction with her symptoms, was concerning for a catecholamine-secreting tumor. Work-up was significant for a strongly positive 24-hour urine catecholamine test. Despite having a normal renal ultrasound, abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a left adrenal mass measuring 2.5× 3.1× 3.9 cm (Figure 2A–B). MRI of the chest was unremarkable. Subsequently, she underwent an I-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan showing an area of radiotracer uptake much larger than expected for a normal adrenal gland (Figure 2C). Both findings were consistent with a left-sided adrenal pheochromocytoma.

Figure 2.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging showing the adrenal mass (A, B) and the I-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine scan revealing increased radiotracer uptake (C).

Treatment

A presumptive diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was made, and the patient underwent a laparoscopic left adrenalectomy. Preoperative blood pressure was optimized with doxazosin and atenolol. Intraoperatively, a left adrenal mass adherent to the left renal vein was identified and removed without complications. The lesion was sent to pathology for histological and immunochemical examination.

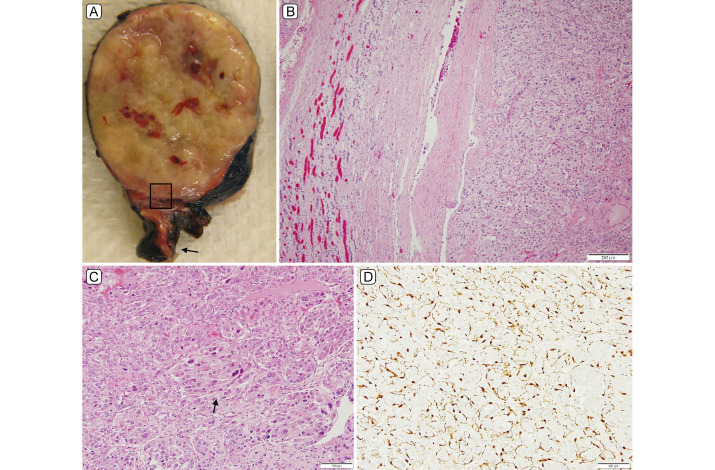

Pathologic examination of the left adrenal mass revealed a 4 cm encapsulated pheochromocytoma without capsular invasion and negative resection margins (Figure 3). A number of atypical histological features were present, including vascular invasion, atypical mitoses, necrosis, large nest size, spindling, and marked nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemistry showed tumor cell positivity for succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunits A and B, indicating retained SDH complex expression. S100 immunostain highlighted sustentacular cells in the periphery of tumor nests imparting a classic zellballen pattern (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

A, Left adrenal mass gross pathology, encapsulated homogenous yellow and focally hemorrhagic mass with attached background adrenal (A, arrow). B, Area corresponding to inset in 3A with adjacent adrenal gland on left, capsule center, and pheochromocytoma on right displaying large polygonal cells containing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm displaying the typical nested tumoral architecture (hematoxylin-eosin [H&E] stain, original magnification ×100). C, Atypical features (arrow), including expanded nests, spindling and cytonuclear atypia (H&E stain, original magnification ×200). D, S100 immunostain highlighting nuclei and cytoplasm of sustentacular cells at the periphery of tumor nests (original magnification ×200).

Five months postoperatively, she was normotensive, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye, color vision was full, and there was complete resolution of the original funduscopic findings (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fundus photographs of the right eye (A) and left eye (B) 5 months following tumor resection.

Differential Diagnosis

A large number of pediatric hypertension cases are attributable to secondary causes. The most common causes in children include renal parenchymal or vascular disease and aortic coarctation. Less commonly, endocrine disorders, including primary hyperaldosteronism and thyroid disorders can cause hypertension in children. Pheochromocytomas are an even less frequent cause.1 The differential diagnosis can be narrowed by the patient’s signs and symptoms, physical examination, and ancillary testing, including laboratory examinations and imaging. As in our case, definitive diagnosis is often established by the histological and immunochemical examination of the excised lesion.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Pheochromocytoma is a rare but potentially lethal endocrine cause of secondary hypertension, requiring prompt diagnosis and adequate management. Hypertension secondary to pheochromocytoma in children is more commonly sustained than paroxysmal.2 This is in contrast to our patient, whose blood pressure was normal before experiencing a hypertensive crisis. A hypertensive crisis is defined as blood pressure equal to or higher than 180/110 mm Hg with or without end-organ damage.3 In paroxysmal cases, the diagnosis can be particularly challenging. High clinical suspicion and careful review of symptoms is warranted for early detection of pheochromocytomas.

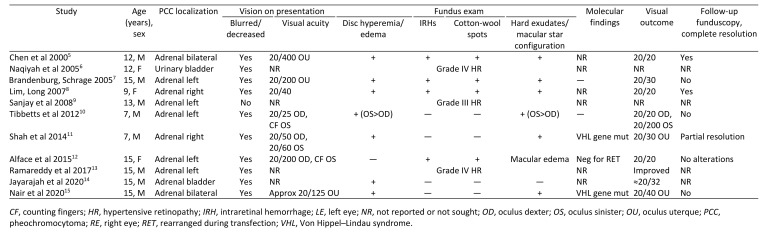

The significant rise in blood pressure can lead to malignant hypertension. Malignant hypertension is defined as severe hypertension, usually higher than 180/110 mm Hg accompanied by end-organ damage, including the heart, brain, kidneys and eyes.4 After reviewing the relevant literature, there have only been 11 reported cases of hypertensive retinopathy secondary to pheochromocytoma in children (Table 1).5–15 Blurry vision was among the most common presenting symptom (10/11 cases), and 8 of 11 cases were evaluated by ophthalmology before further diagnostic workup. Although our patient did not report blurry vision on presentation, the visual acuity was decreased and dilated funduscopic examination revealed grade IV hypertensive retinopathy. This highlights the recommendation for retinal examination in children with hypertension, as stated with grade C evidence by Rabi et al.16 In adults, a thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed when blood pressure is higher than 180/110 mm Hg.17

Table 1.

Reported cases of pheochromocytoma and hypertensive retinopathy in children

Malignant hypertension in children can lead to permanent vision loss, as noted by a case series of four patients.18 This is predominantly due to optic neuropathy or macular atrophy. Browning et al reported that children with decreased visual acuity at presentation, in the context of secondary hypertension, had a worse visual outcome. In our literature review, 4 reported cases of hypertensive retinopathy secondary to pheochromocytoma led to decreased visual acuity with residual lesions on funduscopy. In 3 of those, the visual acuity at presentation was poor, and all patients had grade IV hypertensive retinopathy.

Although most pheochromocytoma cases are sporadic, almost 40% are associated with germline mutations.19 The mutated genes are responsible for syndromes such as Von Hippel Lindau (VHL), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2).20 Two reported cases were due to VHL gene mutations, with one leading to pulmonary metastases and the other to bilateral pheochromocytomas. Therefore, the comorbidities associated with these syndromes make further testing of the utmost importance when a genetic cause is suspected.

In conclusion, pheochromocytoma is a rare but potentially lethal cause of hypertensive emergency in children. It can lead to hypertensive retinopathy with visual loss, which can be permanent if hypertension is not treated in an adequate and timely fashion. Impaired visual acuity at presentation has been associated with worse visual outcomes in secondary hypertension18; thus, consultation for a comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation is recommended when hypertensive crisis or malignant hypertension is identified.17.21 Children with hypertensive retinopathy may have more difficulty describing visual changes compared with adults. As a result, retinal examination has been recommended (grade C evidence) for children with hypertension for evaluation of end-organ damage.16 In rare cases, the ophthalmologist may be the first healthcare worker to detect end-organ damage secondary to malignant hypertension. In these cases, the patient should be promptly referred for further work-up to determine the underlying cause and management of hypertension.

References

- 1.Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Messerli FH. Secondary arterial hypertension: when, who, and how to screen? Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1245–54. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:295–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131:1949–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen TY, Liang CD, Shieh CS, et al. Reversible hypertensive retinopathy in a child with bilateral pheochromocytoma after tumor resection. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000;99:945–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naqiyah I, Rohaizak M, Meah FA, et al. Phaeochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. Singapore Med J. 2005;46:344–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandenburg VM, Schrage N. Hypertensive retinopathy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:187. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0325-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.I-Linn ZL, Long QB. An unusual cause of acute bilateral optic disk swelling with macular star in a 9-year-old girl. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2007;44:245–7. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20070701-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanjay KM, Partha PC. The posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:953–5. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tibbetts MD, Wise R, Forbes B, et al. Hypertensive retinopathy in a child caused by pheochromocytoma: Identification after a failed school vision screening. J AAPOS. 2012;16:97–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah V, Zlotcavitch L, Herro AM, et al. Bilateral papillopathy as a presenting sign of pheochromocytoma associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:623–8. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S60725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alface MM, Moniz P, Jesus S, Fonseca C. Pheochromocytoma: clinical review based on a rare case in adolescence. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211184. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramareddy R, Alladi A. Adrenal mass: unusual presentation and outcome. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38:256–60. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_33_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayarajah U, Herath KB, Fernando MH, Goonewardena S. Phaeochromocytoma of the urinary bladder presenting with malignant hypertension and hypertensive retinopathy. Asian J Urol. 2020;7:70–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair A, Vijayaraghavan A, Alexander P, et al. More than it meets the eye! Vision loss as a presenting symptom of von Hippel–Lindau disease. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2020;15:314. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_24_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabi DM, McBrien KA, Sapir-Pichhadze R, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2020 comprehensive guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:596–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peixoto AJ. Acute severe hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1843–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1901117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browning AC, Mengher LS, Gregson RM, Amoaku WM. Visual outcome of malignant hypertension in young people. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:401–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.5.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: From genetics to personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:101–11. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumann HPH, Young WF, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1806651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–57. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]