As one of the most severe forms of ocular trauma, open-globe injury (OGI) causes significant vision loss. Timely and meticulous repair of these injuries can improve patient outcomes. This video-based educational curriculum is intended to serve as an efficient yet comprehensive reference for OGI repair. We hope that these video-based articles help surgeons and trainees from around the world find answers to specific surgical questions in OGI management. The curriculum has been divided into six separate review articles, each authored by a different set of authors, to facilitate a systematic and practical approach to the subject of wound types and repair techniques. The fifth article highlights special considerations in the management of full-thickness scleral wounds during OGI repair.

Curriculum Editors

Surgical Exploration and Careful Peritomy

Scleral wounds are often difficult to visualize without reflection of the overlying conjunctiva, Tenon’s capsule, clot, and occasionally intraocular contents such as uvea or vitreous.1,2 If the scleral wound is not adequately exposed at the onset of surgery or if the site of rupture is unknown, a 360° peritomy should be performed to provide good surgical exposure. The peritomy is usually made at the limbus and should be initiated tangentially to but never directly over the area of suspected injury. Initial radial relaxing incisions are made at the 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock positions followed by blunt dissection with blunt Wescott scissors extending posteriorly. Careful dissection of each of the four oblique quadrants should be performed to locate any scleral wound, which can be signaled by hemorrhage or uveal prolapse from the posterior sclera. It is very important to dissect down to bare sclera and avoid dissection in the plane between the conjunctiva and Tenon’s capsule. A gush of serosanguinous fluid or blood may signal the presence of a rupture in that quadrant (Video 1, Appendix 1).

Video 1.

Peritomy creation and posterior exploration in open-globe injuries. [LINK TO VIDEO]

Proper wound exposure is essential for good repair, and although a single scleral wound is most common, multiple wounds may be present at any given time. Sometimes, it can be helpful to isolate the extraocular muscles to allow better access to the injury during repair.

(EKC, YL, TB, GWA)

Cardinal Suture

Proper placement of a cardinal (first) suture ensures proper wound alignment.3 For scleral wounds, the cardinal suture ensures that the globe returns to its proper spherical shape, while in corneal wounds, it helps prevent astigmatism and malalignment.4 Thus, proper placement of the cardinal suture is important for good long-term structural and visual outcomes (Video 2, Appendix 2).

Video 2.

Cardinal suture placement at the limbus in open globe injuries. [LINK TO VIDEO]

If a wound extends from the cornea to the sclera, the limbus is an easily identifiable landmark, which can be used to align wound edges. The first step is to extensively clear the limbal wound of adherent episcleral tissue. Next, a cardinal suture (9-0 nylon) should be placed at the limbus to align the wound and create a circular limbus without gaps prior to proceeding with corneal or scleral repair.5 For wounds oriented in a zigzag manner, initial sutures should be placed at wound angles in a ship-to-shore fashion (see Video-based surgical curriculum for open-globe injury repair, III: surgical repair) to correctly align the wound.

(EKC, YL)

The “50% Rule” versus Close-As-You-Go

Various techniques may be necessary to achieve proper closure of scleral wounds depending on the orientation and length of each wound. All scleral wounds should be closed with interrupted nylon sutures, and the wound should first be carefully cleaned of Tenon’s capsule and clot in order to visualize the extent of the wound and identify the scleral wound edge. If there is no significant uveal prolapse or if the wound is small, the entire wound can be exposed with the goal of identifying the halfway point. Then, the first suture may be placed halfway along the length of the wound, with subsequent sutures bisecting the remaining length until the wound is fully closed. This technique is known as the “50% rule”1 and allows for even spacing between sutures and good alignment to achieve a watertight seal6 (Video 3, Appendix 3).

Video 3.

“50% rule” versus “close-as-you-go” techniques for scleral wound closure. [LINK TO VIDEO]

Radial wounds, wounds with significant uveal prolapse, poor exposure, or far posterior extension past the equator, as well as large gaping scleral wounds should also be cleaned with a goal of gaining adequate surgical exposure5; however, these wounds are sutured not according to the 50% rule but rather progressively, from the anterior to posterior ends, in a “close-as-you-go” method. This prevents tissue extrusion from the wound when the eye is manipulated during suturing. It also helps to reposit intraocular contents sequentially, especially when there is significant extrusion.

Notably, surgical repair of scleral wounds that extend very far posteriorly may not require complete repair. When scleral wounds extend far past the equator of the globe, it can be difficult to adequately visualize and access the most posterior portions of the wound without significant manipulation of the globe, which may increase the risk of expulsion of intraocular contents. Wounds with far-posterior scleral wounds have also been shown to have worse clinical outcomes.7 Many surgeons therefore opt to repair all accessible portions of the scleral wound and allow the most posterior portions to close by secondary intention, although there is some controversy among experts on this point.

(EKC, YL)

Muscle Involvement

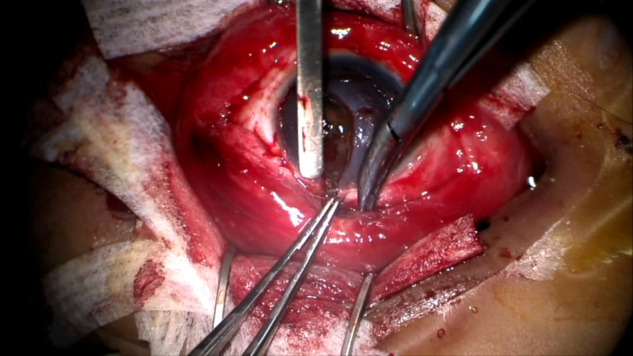

It may be difficult to delineate the full extent of a scleral wound if it extends posterior to the insertion of a rectus muscle. Exploring the extent to which a wound travels behind an extraocular muscle can be accomplished using Gass muscle hooks to isolate and lift the muscle from the sclera while rotating the eye gently.8 Additionally, 2-0 silk can be slung around the extraocular muscle and then manipulate the globe. However, excessive manipulation of the globe in an attempt to avoid muscle damage during wound repair may increase intraocular pressure and cause expulsion of intraocular contents. Thus, temporary detachment of extraocular muscles may provide improved exposure and access to the scleral injury and decrease the risk of iatrogenic injury to the muscle during wound repair (Video 4, Appendix 4). Proper technique of suturing and disinsertion of extraocular muscles is discussed in a previous article of this review series (see Video-based surgical curriculum for open-globe injury repair, III: surgical repair).

Video 4.

Scleral wound repair beneath an extraocular muscle. [LINK TO VIDEO]

Transected or avulsed muscles should be reattached to preserve extraocular muscle function. Disinserted muscle can sometimes be found behind its normal insertion site, because it is held in place by check ligaments and the intermuscular septum. Complete transections of extraocular muscles are more difficult to repair, because the muscle may retract into the posterior orbit, possibly requiring an orbitotomy to retrieve. On the other hand, partial transections of muscles may easily be repaired by reattaching the two ends of the muscle with nonabsorbable sutures. If a muscle is severely damaged, at least 5-6 weeks should be allowed to monitor potential return of function.9

(EKC, YL, TB)

Key Learning Points

If a scleral wound is suspected, a 360° peritomy should be performed to identify the location of the wound and to obtain good surgical exposure for repair.

During blunt dissection into each oblique quadrant, a gush of serosanguinous or bloody fluid may signal the presence of a rupture.

Proper cardinal suture placement can ensure optimal structural and visual outcomes after open-globe injury.

For corneoscleral wounds, place the initial suture at the limbus to align the rest of the wound.

For jagged wounds, place sutures at wound angles to properly align the wound.

Circumferential wounds should be closed by bisecting the wound with interrupted sutures, allowing for proper wound alignment and even spacing between sutures.

Radial wounds and large wounds with risk of uveal prolapse should be closed in a close-as you-go approach to prevent tissue extrusion when manipulating the eye for posterior visualization.

Temporary detachment of a rectus muscle overlying a posterior scleral wound provides better exposure and access to the wound, as well as decreases the risk of iatrogenic injury to the muscle during wound repair.

Detaching the extraocular muscle when a laceration extends deep to the muscle reduces the risk of expulsion of intraocular contents from increased IOP due to excessive globe manipulation.

Partially transected muscles may be repaired with direct apposition of the edges, whereas muscles that are completely transected may be lost in the posterior orbit.

Contributor Information

curriculum editors:

References

- 1.Sullivan P. The Open Globe—Surgical Techniques for the Closure of Ocular Wounds (ebook) Eyelearning Ltd; 2013. Scleral wounds; pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chronopoulos A, Ong JM, Thumann G, Schutz JS. Occult globe rupture: diagnostic and treatment challenge. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63:694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macsai MS, Fontes BM. Trauma suturing techniques. In: Macsai MS, editor. Ophthalmic Microsurgical Suturing Techniques. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao R, Miller JB, Grob S. Limbus to limbus corneal laceration from nail gun injury. In: Grob S, Kloek C, editors. Management of Open Globe Injuries. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. pp. 103–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn F, Pelayes D. Management of the ruptured eye. Eur Ophth Rev. 2009;3:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamill M. Corneal and scleral trauma. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15:185–94. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleicher ID, Tainsh LT, Gaier ED, Armstrong GW. Outcomes of zone 3 open globe injuries by wound extent: subcategorization of zone 3 injuries segregates visual and anatomic outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2023;130:379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Zyl T, Grob S. Zone III rupture requiring muscle take-down after hockey stick injury. In: Grob S, Kloek C, editors. Management of Open Globe Injuries. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. pp. 175–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Monte MA. Management of direct extraocular muscle trauma. Amer Orthoptic J. 2004;54:1. [Google Scholar]