Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to elucidate the impact of upadacitinib, a Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)-specific inhibitor, on experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) and explore its underlying mechanisms.

Methods

We utilized single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (scATAC-seq) to investigate the JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 12 patients with Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) disease and cervical draining lymph node (CDLN) cells of EAU. After treating EAU with upadacitinib, we analyzed immune cell gene expression and cell–cell communication by integrating scRNA data. Additionally, we applied flow cytometry and western blot to analyze the CDLN cells.

Results

The JAK/STAT pathway was found to be upregulated in patients with VKH disease and EAU. Upadacitinib effectively alleviated EAU symptoms, reduced JAK1 protein expression, and suppressed pathogenic CD4 T cell (CD4TC) proliferation and pathogenicity while promoting Treg proliferation. The inhibition of pathogenic CD4TCs by upadacitinib was observed in both flow cytometry and scRNA data. Additionally, upadacitinib was found to rescue the interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15)+ CD4TCs and CD8 T and B cell ratios and reduce expression of inflammatory-related genes. Upadacitinib demonstrated the ability to inhibit abnormally activated cell–cell communication, particularly the CXCR4-mediated migration pathway, which has been implicated in EAU pathogenesis. CXCR4 inhibitors showed promising therapeutic effects in EAU.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the JAK1-mediated signaling pathway is significantly upregulated in uveitis, and upadacitinib exhibits therapeutic efficacy against EAU. Furthermore, targeting the CXCR4-mediated migration pathway could be a promising therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: upadacitinib, JAK1, scRNA, scATAC, uveitis

In autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, immune dysregulation and imbalanced cytokine secretion are central to their pathogenesis. Specifically, disequilibrium of immune homeostasis within the eye can result in autoimmune uveitis (AU), a disorder characterized by autoimmunity, including Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) disease. In the developed world, AU is the primary cause of severe visual impairment, accounting for 10% to 15% of all cases of blindness,1 and it affects young adults in contrast to other conventional ocular diseases such as age-related macular degeneration and cataract. Although AU may be localized to the eye, it can also manifest systemically with other autoimmune diseases. The most widely used animal model for AU, experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU), has greatly contributed to our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and potential therapies for this refractory and sight-threatening disease. However, the specific pathogenic mechanism of AU remains unclear, and further targeted therapies with minimal side effects are essential.

Monoclonal antibodies developed two decades ago have gained significant utility in blocking the actions of disease-causing cytokines. However, emerging agents known as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which can simultaneously target multiple pathogenic cytokines by impeding downstream JAK signal transducer and transcriptional activator (JAK/STAT) pathways, are now gaining increasing importance. Upadacitinib (UPA) is a selective and reversible JAK1 inhibitor approved for treating various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, atopic dermatitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn's disease.2–7 Meanwhile, prior investigations into the effects of UPA in individuals diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn's disease have yielded noteworthy findings regarding elevated rates of infection, including shingles, nonfatal stroke, pulmonary embolism, and thrombosis.8–10 These outcomes emphasize the importance of considering potential risks and side effects associated with UPA therapy. The therapeutic effects of UPA are thought to arise from its selective targeting of JAK1, which plays a pivotal role in the signal transduction of several proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-23, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ).11,12 Notwithstanding the notable progress in the application of JAK1 inhibitors in treating various diseases, the precise underlying mechanism of JAK1 inhibitor therapy in uveitis remains elusive. Furthermore, there exists a dearth of studies investigating the efficacy of the JAK1 inhibitor UPA in treating uveitis. Therefore, further research is necessary to elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms of JAK1 inhibition in uveitis, which will potentially enhance our understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease and facilitate the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Single-cell sequencing technology has gradually become a powerful tool for immunologists. Single-cell assays for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (scATAC-seq) have emerged as a novel approach to depict single-cell–specific epigenomic regulatory landscapes.13 This technology enables genome-wide identification of cell-type–specific cis-elements, mapping of disease-associated enhancer activity at a single-cell resolution. In our investigation, we performed an integrative analysis of scATAC-seq and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to assess the impact of UPA disposition on immune cells of VKH patients and EAU models. Our findings revealed upregulation of the JAK/STAT pathway in patients with VKH disease and EAU models, providing a comprehensive landscape of the immune cells influenced by UPA. Furthermore, UPA administration resulted in a reversal of the pathological changes observed in interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15)+ CD4 T cell (CD4TC), CD8TC, and B cell (BC) upregulation. ISG15 is known to be significant ubiquitin-like protein induced by IFN through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.14 We also identified CXCR4 as a mediator of abnormally elevated gene in the JAK1-mediated signaling pathway during EAU. This novel discovery highlights the potential of UPA as a promising therapeutic target for uveitis treatment and further extends our understanding of the immunomodulatory mechanisms of JAK1-mediated signaling pathway in uveitis.

Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6J mice 6 to 8 weeks old were procured from the Guangzhou Animal Experiment Center and were reared under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and institutional policies (Sun Yat-Sen University).

Human Projects

A total of 24 participants, including 12 healthy controls (HCs) and 12 patients with VKH disease, were recruited from the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (2019KYPJ114). Exclusion criteria included comorbidities such as cancer, immune dysfunction, hypertension, diabetes, and steroid use. Gender and age were matched between the HC and VKH disease groups. The diagnosis of VKH disease was performed in compliance with the diagnostic criteria established by the International Symposium on VKH Disease.15

Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis Model Establishment

We prepared an emulsion by adding Mycobacterium tuberculosis toxin (Difco Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to complete Freund's adjuvant (Difco Laboratories) to achieve a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL, which was then mixed with an equal volume of interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (1–20) (IRBP1–20; 2 mg/mL; GiL Biochem, Shanghai, China) PBS solution. Subsequently, 200 µL of the emulsion was subcutaneously injected into anesthetized mice for immunization. In addition, a 0.25-µg intraperitoneal injection of pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA, USA) was administered on the day of immunization and the following day. Fundus photography was employed to assess clinical scores on day 14 after immunization, with eyeballs taken from sacrificed mice to create pathological sections. Both clinical and pathology scores were graded using previously published evaluation criteria ranging from 0 to 4.16

Treatment of Mice and Cervical Draining Lymph Nodes

UPA (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, 0.1%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Following immunization, the UPA group was intraperitoneally administered UPA (5 mg/kg/day) from day 0 to day 14, and the EAU control group received an equal volume of PBS solution. The CXCR4 inhibitor MSX-122 (MedChemExpress) was given at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day, with other experimental conditions being identical to those of the UPA group. Cervical draining lymph node (CDLN) cells were incubated with IRBP1-20 (20 µg/mL) with or without MSX-122 (5 nM) for 72 hours, after which flow cytometry was used to obtain cell samples.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

On day 14, mice were euthanized, and their eyeballs were harvested, followed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours. The eyeballs were then embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

CDLN cells were isolated and subjected to staining with the following antibodies: anti-mouse CD4 (Biolegend, USA, cat no. 100434) for surface markers. For intracellular labeling, the cells were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 5 ng/mL), Brefeldin A (1000 ng/mL), and ionomycin (500 ng/mL) for 5 hours. The intracellular factors including IL-17A (Biolegend, USA, cat. no. 506930), IFN-γ (Biolegend, USA, cat. no. 505808), and Foxp3 (Invitrogen, USA, cat. no. 11-5773-82) were then stained after fixation and permeabilization. Flow cytometry was employed to analyze the cells, and FlowJo 10.6.2 software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA) was used for further data analysis.

Western Blotting

After obtaining the CDLN cells, protein samples were prepared according to the protein extraction kit instructions. Equal amounts of protein were separated via gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a membrane. Following blocking with 5% non-fat milk, JAK1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with the second antibody for 2 hours after washing. Blots were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) with a molecular imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Grayscale values were determined using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Single-cell suspensions from CDLN samples were converted into barcoded scRNA-seq libraries using the Chromium Single Cell 5′ library, Gel Bead, and Multiplex Kit, as well as the Chip Kit (10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA). The preparation of the scRNA libraries was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using the Chromium Single Cell 5′ v2 Reagent kit (cat. no. 120237; 10x Genomics). Quality checks were performed using FastQC software. The sequencing data were initially processed using Cell Ranger 5.0.0 software. For data integration and preliminary collation, we utilized the R package Seurat 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).17 In the quality control step, we excluded cells with fewer than 200 genes or more than 15% mitochondrial gene ratio. We implemented the Harmony R 1.0 package to mitigate batch effects across samples. Differential expression analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon test, as implemented in the “FindAllMarkers” function of the Seurat R package, for each cell type between different groups. Additionally, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two groups using the “FindMarkers” function in Seurat, with the following criteria: (1) log fold change > 0.25, (2) adjusted P < 0.05, and (3) >5% of cells in either test group.

Gene Functional Annotation

Following the identification of DEGs between two groups, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis using the Metascape webtool.18 Among the top 50 enriched GO terms, we selectively curated five to 20 EAU-related GO terms or pathways to showcase, using the ggplot2 R package.19 Individual cells were assessed for their gene expression of certain biological functions through scoring based on the mean normalized expression of relevant genes. We obtained genes associated with the JAK/STAT pathway from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway dataset.

Cell–Cell Communication

The analysis of cell–cell communication was conducted using the normalized expression matrices generated from Seurat and was further analyzed and visualized with the R package CellChat 1.5.0.20 To acquire the roster of established ligand–receptor pairs, we consulted CellChatDB, a literature-supported database that furnishes knowledge on interactions between ligands and receptors in both mice and humans. Our approach entailed the identification of overexpressed ligands or receptors in varied cell types, followed by the computation of communication probabilities by taking into account all ligand and receptor interactions linked to each signaling pathway.

Single-Cell ATAC-Seq

Following the established protocols for sample processing, library preparation, and instrument and sequencing settings on the 10x Genomics Chromium X platform, we conducted scATAC-seq data reads aligned to the GRCh38 (hg38) reference genome and quantification using the “cellranger count” function, followed by data aggregation using the “cellranger atac aggr” function. Quality control and subsequent analyses were performed using the R package Signac 1.8.0.21 In our scATAC-seq data analysis, we applied strict filtering criteria, which included excluding cells with fewer than 2000 unique fragments and an enrichment at transcription start sites below 2. Additionally, we removed cells that mapped to blacklist regions based on the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements project reference. To reduce any batch effects, we utilized the Harmony 1.0 R package. Next, we calculated gene activity scores for each cell using the “GeneActivity” function in Signac, and we used these scores to identify cell types. Finally, we employed the “FindMarkers” function in Signac to identify differentially accessible peaks between the different experimental groups.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA), employing either an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA. The results are reported as mean ± SD. P > 0.05 was not considered to be significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA data have been deposited at the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) with the project numbers PRJCA016731 and PRJCA004696.

Results

Identification of Cell Types and JAK-Mediated Inflammation During EAU and VKH

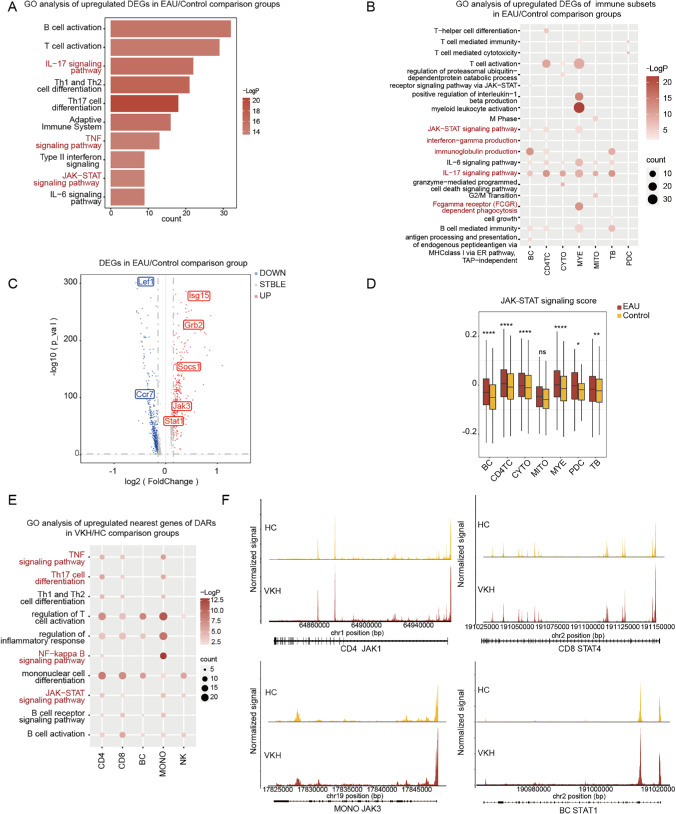

To clarify the specific role of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in AU, scRNA-seq was performed on CDLN cells of the control and EAU groups. Based on the marker genes for various cell types, we authenticated eight major immune cell lineages: BCs, CD4+ helper T cells (CD4TCs), cytotoxic cells (CYTOs), TBs (expressed as both T and BC markers), myeloid cells (MYEs), mitotic T cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs) (Supplementary Figs. S1A, S1B). We subdivided BCs, CD4TCs, CYTOs, and MYEs into detailed subsets ulteriorly (Supplementary Figs. S1C–S1J, Supplementary Table S1). We compared the transcriptional characteristics of DEGs between the control group and EAU. Through the application of GO and pathway analyses, we found that the upregulated DEGs in CDLN cells were commonly enriched in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and inflammation-related pathways, such as the IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways (Fig. 1A). Similarly, further enrichment analysis of the seven subpopulations also revealed a significant increase in the activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in the BC, CD4TC, and MYE subsets (Fig. 1B). Our study noticed the activation of multiple inflammatory pathways in various immune cell types, including Fc gamma receptor (FCGR)–dependent phagocytosis, IFN-γ production, and immunoglobulin production. Furthermore, our analysis of the DEGs using a volcano plot revealed upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway–related genes, such as Socs1, Jak3, and Stat1, in CDLN cells of EAU mice compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1C). We extended our analysis to the DEGs from the seven subpopulations and the subgroups of BC, CD4TC, and CD8TC. We observed a significant increase in the expression of JAK/STAT signaling pathway–related genes, such as the Socs and Jak families, including Socs7, Socs3, and Jak3, on BC subgroups and Jak3 and Socs3 on CD4TC and CD8TC subgroups (Supplementary Fig. S2). As such, we calculated JAK/STAT signaling scores to evaluate the degree of manifestation enhanced by EAU and found that the JAK/STAT signaling score of EAU significantly increased compared to that of the control group among the subpopulations (Fig. 1D). Our investigation provides the evidence of elevated JAK/STAT signaling pathway activation in EAU.

Figure 1.

Identification of cell types and JAK-mediated inflammation during EAU and VKH. (A) Representative GO terms and pathways enriched in upregulated DEGs of CDLN cells in the EAU and control comparison groups. (B) Representative GO terms and pathways enriched in upregulated DEGs of immune subsets in the EAU and control comparison groups. (C) Volcano plot illustrates the DEGs of CDLN cells in the EAU and control comparison groups; upregulated genes are shown in red and downregulated genes are shown in blue. (D) A box plot displays the JAK/STAT signaling scores in immune subsets between the EAU and control groups. (E) Representative GO terms and pathways enriched in upregulated nearest genes of differentially accessible chromatin regions (DARs) of immune subsets in the VKH and HC comparison groups. (F) Genome browser tracks showing single-cell chromatin accessibility in the JAK1, JAK3, STAT4, and STAT1 loci in CD4TCs, CD8TCs, monocytes, and BCs, respectively.

scATAC-seq has been appreciated as a cutting-edge approach to depict single-cell–specific epigenomic regulatory landscapes.22 Here, we developed scATAC-seq datasets to elucidate the landscape in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) derived from healthy controls (n = 12) and patients with VKH disease (n = 12). The human immunophenotypic blood cells were identified as five major immune cell lineages based on the corresponding marker genes with each cell type: natural killer cells, CD8TCs, monocytes, BCs, and CD4TCs (Supplementary Figs. S3, S4). Through our analysis of chromatin accessibility in the two groups, we have identified differentially accessible chromatin regions (DARs) and the nearest genes of DARs. Enrichment analysis indicated that the nearest genes of DARs across cell subpopulations were enriched in GO terms related to JAK/STAT, TNF, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and Th17 cell differentiation (Fig. 1E). Also of note, our analysis of gene-accessible chromatin regions related to the JAK/STAT signaling pathway revealed a significant increase in the locus of JAK1 in CD4, JAK3 in monocytes, STAT4 in CD8, and STAT1 in BCs among patients with VKH disease (Fig. 1F). Overall, these findings underscore the potential involvement of JAK/STAT signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of AU and highlight its potential as a therapeutic target for managing this condition.

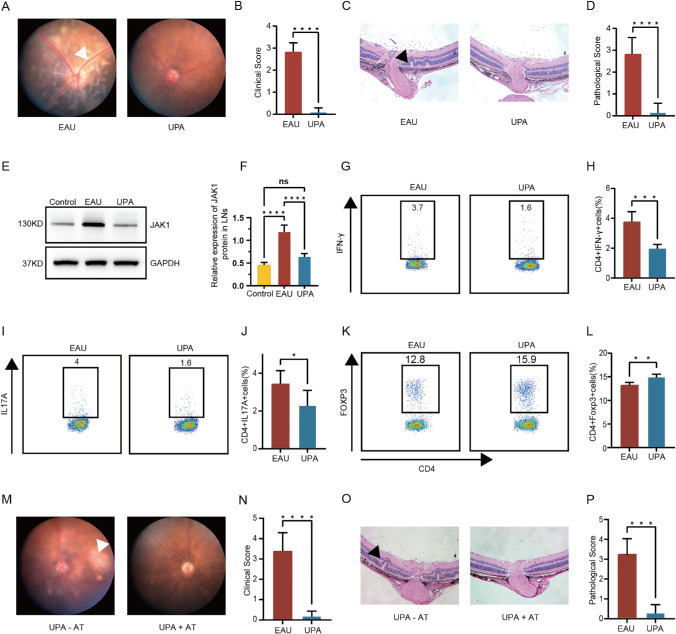

Inflammation Induced by EAU Rescued by UPA Clinically and Histologically

To assess the potential therapeutic efficacy of JAK/STAT signaling pathway inhibition for uveitis treatment, we conducted a preliminary trial using the JAK1-specific inhibitor UPA and the EAU model. We immunized C57BL/6J mice with IRBP1–20 to induce the EAU model and treated it with UPA intraperitoneally (5 mg/kg/day) from day 0 to day 14. The fundus photography and histopathological severity and were evaluated for the EAU and UPA-treated groups to calculate the clinical and pathological scores of their fundus inflammation, respectively. By comparing fundus photography between the two groups, it is apparent that, after UPA treatment, the uveitis that originally presented in the fundus of EAU mice, including extensive retinal edema, blood vessel leakage, and retinal choroid folding, had been noticeably ameliorated (Figs. 2A, 2B). Histopathological analysis indicated symptom alleviation in EAU mice, and the clinical and histopathological scores were accordingly prominently reduced (Figs. 2C, 2D). Additionally, we observed a decrease in the expression of JAK1 in EAU mice after UPA treatment, indicating that JAK1-mediated signaling pathways may be key players in EAU therapy (Figs. 2E, 2F, Supplementary Fig. S5A).

Figure 2.

Inflammation induced by EAU rescued by UPA clinically and histologically. (A, B) Day 14 fundus images following immunization in EAU mice and UPA-treated mice are presented as a representative example (A), with white arrows highlighting the presence of inflammatory exudation and linear lesions. Clinical scores of the two groups (n = 5/group) are compared using column charts (B) (C, D) Day 14 H&E-stained images following immunization in EAU mice and UPA-treated mice are presented as representative example (C), with black arrows highlighting retinal folding. Pathological scores of the two groups (n = 5/group) are compared using column charts (D). Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ****P < 0.0001. (E, F) Elevated protein levels of JAK1 were detected in CDLN cells of EAU compared with normal mice but they decreased in UPA-treated mice (n = 5/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA, ****P < 0.0001. (G–L) At day 14 following immunization, the percentages of CD4+ cells expressing IFN-γ (G, H), IL-17A (I, J), and Foxp3 (K, L) in the CDLN cells were evaluated in both EAU mice and those treated with UPA (n = 5/group). (M, N) Day 14 fundus images following injection of IRBP1–20-specific CD4+ T cells treated with or without UPA are presented as representative example (M), with white arrows highlighting the presence of inflammatory exudation and linear lesions. Clinical scores of the two groups (n = 5/group) are compared using column charts (N). (O, P) Day 14 H&E-stained images of the two groups are presented as representative example (O), with black arrows highlighting retinal folding. Pathological score of the two groups (n = 5/group) are compared using column charts (P). Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Because of the significance of CD4TCs during the development of AU, we leveraged flow cytometry to anatomize the effect of UPA therapy on CD4TCs from CDLN cells. Compared with UPA-untreated mice, the proportion of IFN-γ–producing CD4TCs (Th1 cells) and IL-17A–producing CD4TCs (Th17 cells) were decreased, whereas regulatory T cells (CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs) were increased after UPA therapy (Figs. 2G–2L, Supplementary Fig. S5B). To further verify the therapeutic effectiveness of UPA in EAU, adoptive transfer experiments were conducted. CD4TCs were isolated from EAU mice on day14 and cultured with IRBP1–20 for 72 hours in the presence or absence of UPA. Meanwhile, we transferred UPA-treated or UPA-untreated CD4TCs into mice and observed that the pathogenicity of CD4TCs was dampened by UPA treatment. Correspondingly, the clinical and histological scores decreased due to UPA therapy (Figs. 2M–2P).

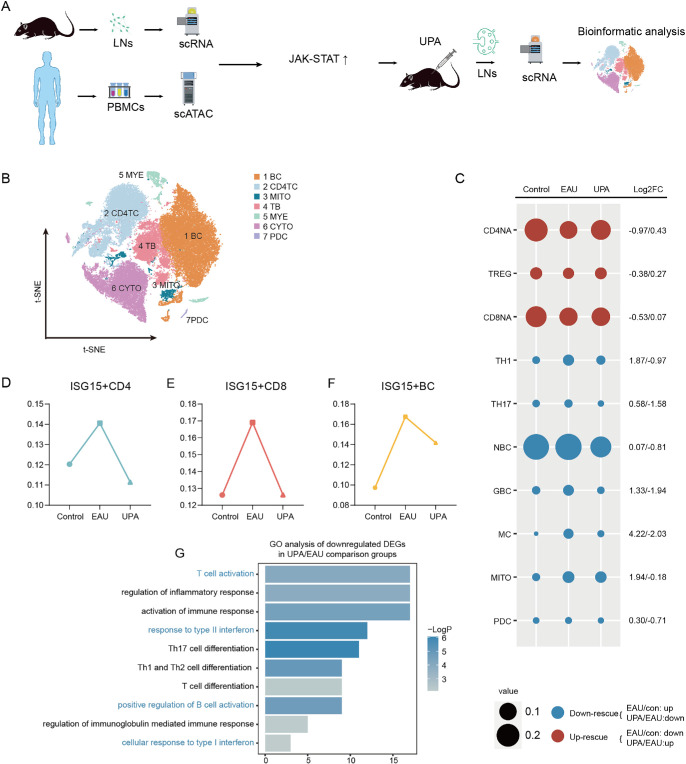

Reconstitution by UPA of Immunocyte Configuration During EAU

To investigate the therapeutic mechanism of UPA in the treatment of EAU, we performed scRNA-seq on CDLN cells obtained from the UPA group. The overall design process of our experiment is illustrated in Figure 3A. Following quality control measures, we obtained a total of 63,369 high-quality cells for further analysis, including 26,022 cells from the control group, 26,972 cells from the EAU group, and 10,375 cells from the UPA group. We integrated all of the cells from the three groups and classified the cells into seven distinct types of immune cells according to the subsets mentioned above (Fig. 3B). We then further subdivided these into subgroups based on specific cellular markers (Supplementary Fig. S5C–S5G). By comparing the composition of these subgroups among the control, EAU, and UPA groups, we identified changes in cell type proportions during EAU and after UPA therapy. Specifically, the proportions of naïve CD4+ T cells (CD4NAs), naïve CD8+ T cells (CD8NAs), and Tregs decreased during EAU, whereas the proportions of Th1, Th17, germinal B cells (GBCs), and monocytes increased (Fig. 3C). In contrast, following treatment with UPA, we observed a rescue in the disordered cell proportions (Fig. 3C), indicating a potential therapeutic effect of UPA in restoring immune system homeostasis. We also found that the cell proportions of the three ISG15+ subgroups (ISG15+ CD4TCs, CD8TCs, and BCs) increased in EAU and decreased following UPA treatment (Figs. 3D–3F), indicating involvement of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in the therapeutic effects of UPA. Furthermore, we performed GO and pathway analyses of downregulated DEGs after UPA treatment and found that they were associated with response to type II interferon, cellular response to type I interferon, T cell activation, and positive regulation of B cell activation (Fig. 3G).

Figure 3.

The reconstitution by UPA of immunocytes configuration during EAU. (A) Experimental design for this study. (B) The t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) clustering of CDLN cells. (C) The cell ratios of different cell types were comparatively analyzed across the three groups, and the log2 fold change values of the relative changes in cell ratios are indicated on the right. (D–F) Line charts depict the proportions of ISG15+ CD4TCs (D), ISG15+ CD8TCs (E), and ISG15+ BCs (F) across three distinct groups derived from scRNA-seq data. (G) Representative GO terms and pathways enriched in downregulated DEGs of CDLN cells in the UPA and EAU comparison groups. P value was derived by a hypergeometric test.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that the elevated JAK1-mediated signaling pathway is altered by UPA treatment, resulting in changes in the proportions of various cell subpopulations and suggesting the potential therapeutic mechanisms for AU.

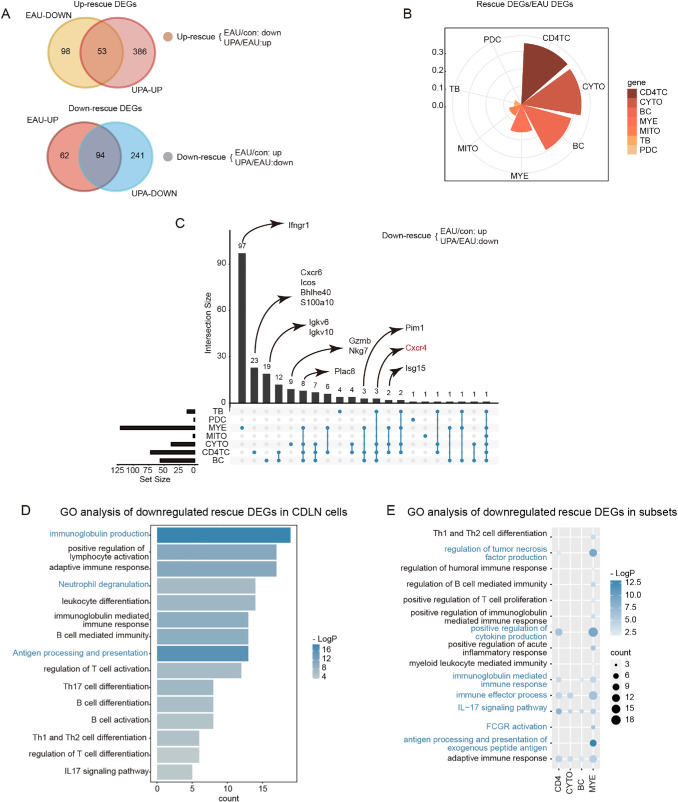

EAU-Associated Gene Expression Alteration in LN Rescued by UPA

Next, we aimed to identify the DEGs among the three groups and investigate the transcriptional alterations induced by EAU and UPA. Our findings revealed that UPA had a significant remodeling effect on the immune environment of EAU mice, as demonstrated by the upregulation of 53 out of 151 downregulated DEGs induced by EAU and the downregulation of 94 out of 156 upregulated DEGs induced by EAU (Fig. 4A). We further referred to these DEGs as “rescue DEGs” and calculated the ratio of rescue DEGs to EAU DEGs as a rescue ratio (RR) to clearly depict the impact of UPA on EAU. The RR was attributed to three major cell types: CD4 cells, CYTOs, and BCs (Fig. 4B). With UpSet plots,23 we demonstrated specific rescue genes among these cell types to further ascertain the potential immunotherapy mechanism of UPA on EAU (Fig. 4C). Our analysis revealed distinct gene expression patterns across different immune cell clusters. Notably, Ifngr1, a Jak-related gene, was found to be expressed exclusively in MYE clusters, whereas Igkv, an antibody-related gene, was found to be expressed exclusively in BCs. Furthermore, inflammation-related genes, such as Cxcr6, Icos, Bhlhe40, and S100a10, were specifically expressed in TCs. Finally, genes related to cytotoxicity, such as Gzmb and Nkg7, were observed to be expressed exclusively in the CYTO clusters (Fig. 4C). Additionally, we observed some genes that showed expression across multiple cell types. Isg15 was found to be a down-rescue gene in both CD4 cells and CYTOs, whereas Cxcr4 was down-rescued in all three BC, CD4, and CYTO cell types. These genes have been associated with the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases.24,25 Consistent with previous research, we identified several genes that could potentially serve as therapeutic targets for EAU, such as Pim1, which could be inhibited to reduce the proportion of Th17 cells and increase the proportion of Tregs.26

Figure 4.

EAU-associated gene expression alteration in lymph nodes rescued by UPA. (A) Venn diagrams illustrate the number of DEGs for EAU, UPA, and rescue conditions. The intersecting regions indicate the number of upregulated rescue DEGs (top) and downregulated rescue DEGs (bottom). (B) Rose diagram displays the proportion of rescue DEGs compared to EAU DEGs. (C) UpSetR plots visualize the downregulated rescue DEGs across different cell types, with key genes labeled at the top. UpSet plots are an alternative to Venn diagrams used to deal with more than three sets. (D) Representative GO terms and pathways enriched in downregulated rescue DEGs in CDLN cells. P value was derived by a hypergeometric test. (E) Representative GO terms and pathways enriched in downregulated rescue DEGs in immune subsets. P value was derived by a hypergeometric test.

Then, we took down-rescue DEGs in CDLN cells to conduct GO enrichment analysis and found that the activation and differentiation of TCs and BCs were decreased, and targeted genes were mainly enriched in pathways associated with immunoglobulin production, antigen processing and presentation, and neutrophil degranulation (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, we conducted GO analysis leveraging immunocytes from the four major cell types, and the downregulated rescue DEGs in CD4 cells were enriched in signaling pathways related to the regulation of tumor necrosis factor production and positive regulation of cytokine production (Fig. 4E). The downregulated rescue DEGs in CYTOs were enriched in immune effector processes, and the immunoglobulin-mediated immune response signaling pathway was enriched in BC (Fig. 4E). The pathways associated with FCGR activation and antigen processing and presentation of exogenous peptide antigen were enriched in MYE (Fig. 4E). These findings suggest that UPA has a powerful capacity to reverse immune disorders caused by EAU and can serve as a potential immunotherapeutic agent for this condition.

Cell Type–Specific Gene Expression Impacted by EAU and UPA

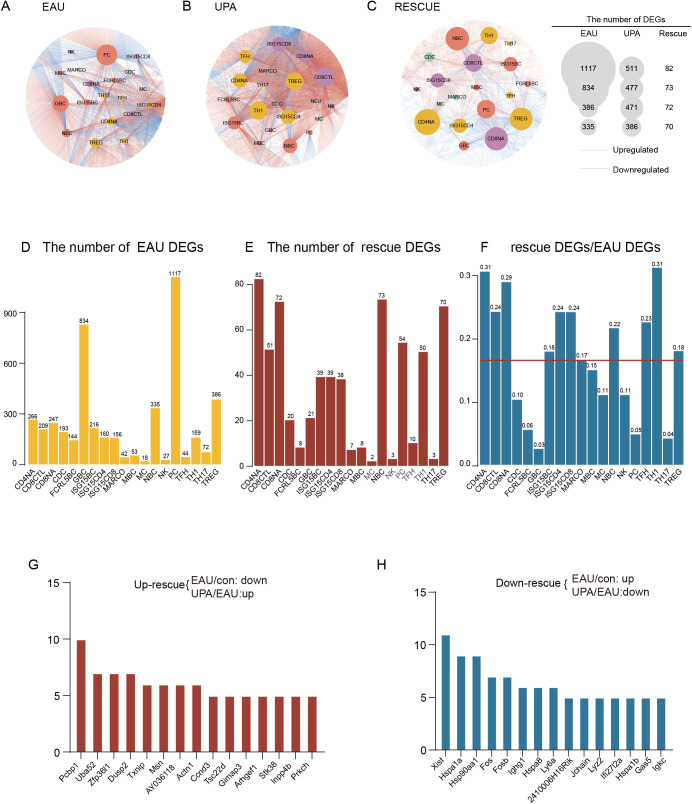

Our findings suggest that, although UPA has a significant overall rescue effect on immunocytes in EAU, it is essential to further investigate the cell type–specific expression of DEGs. To achieve this, we classified the DEGs into subgroups defined in each cell type and constructed gene regulatory networks across 18 types of immunocytes by cytoscape27 (Fig. 5A). In the figure, the sizes of the circles for different subpopulations indicate that EAU and UPA have varying gene regulatory effects on specific cell subpopulations. Notably, plasma B cells (PCs) and GBCs were the two subgroups most significantly affected by gene expression during EAU, highlighting the critical role of autoantibody generation in the development of autoimmune diseases (Fig. 5A). The gene expression level of Tregs was also prominently affected, which fully indicated the important role of Tregs in the pathogenesis of EAU (Figs. 5A, 5D). Moreover, UPA affected TC and BC subsets (Fig. 5B). CD4NA, Treg, and Th1 cells were the top three affected TC subsets based on their large DEG quantities (Fig. 5B). The gene expression patterns of naïve CD4, CD8, BC, Treg, and ISG15+ cells were significantly affected by UPA, further supporting the previous observations (Fig. 5C). In order to elucidate the effect of EAU and UPA treatment on mice more intuitively, we quantitatively ranked the DEGs of different cell types. From the number of rescue DEGs and RR, we observed that the subpopulations of TCs and BCs were both impacted by UPA therapy. To be specific, our investigation revealed that UPA has a robust rescuing effect on naive cells (CD4NA, CD8NA, naive BC [NBC]), Th1 cells, Tregs, and Isg15+ cells. (Figs. 5E, 5F).

Figure 5.

The cell type–specific gene expression impacted by EAU and UPA. (A–C) Network plots depict the EAU (A), UPA (B), and rescue (C) DEGs in various cell types. Plots were generated using Cytoscape software. The internal node color corresponds to the cell type, and the gray edges represent the DEGs. The lines connecting the nodes indicate the attribution of DEGs to their respective cell types. (D–F) Bar plots display the count of rescue DEGs and EAU DEGs, as well as the rescue and EAU DEGs in each subtypes. The red line represents the average proportion of rescue DEGs and EAU DEGs. (G–H) Bar plots demonstrate the frequency of upregulated (G) and downregulated (H) rescue DEGs.

Then, we examined the impact of UPA treatment on gene expression in immunocytes affected by EAU. Specifically, we ranked the frequency of rescue DEGs in immunocytes as up- and downregulated in order to observe the specificity of gene expression affected by EAU and UPA treatment (Figs. 5G, 5H). Our analysis revealed that PCBP1, a multifunctional RNA-binding protein expressed in most human cells,28 was the most impacted upregulated rescue DEG (Fig. 5G). Previous studies have identified PCBP1 as a potential tumor suppressor gene and a regulator of genes involved in the immune response pathway, including the alternative splicing of immune response–related genes in TCs, ultimately participating in the molecular mechanism of rheumatoid arthritis.29 Our findings suggest that UPA may have an immunoregulatory effect on EAU by impacting the expression of PCBP1. Furthermore, we observed that the activator protein-1 (AP-1) family, the heat shock protein (HSP) family, and ISG15–related genes were upregulated during EAU but downmodulated by UPA therapy in more than five cell types, indicating that UPA treatment may have a broader impact on immune-related gene expression. These results provide insight into the potential mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of UPA in the treatment of ocular inflammation.

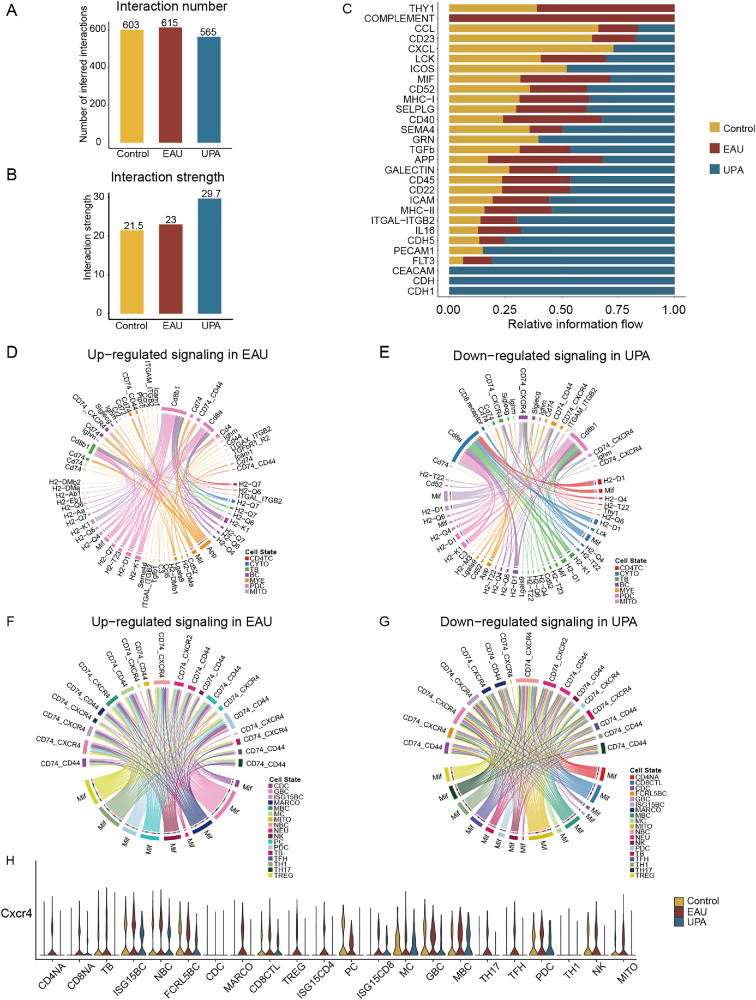

Anomalous Intercellular Communication in EAU Attenuated by UPA

To investigate how cell–cell communication in EAU is altered by UPA therapy, we compared the total number of interactions and interaction strength of the inferred cell–cell communication networks from the control, EAU, and UPA groups leveraging CellChat.20 The number of cell–cell communications among the three groups was compared by bar graphs; the EAU group had the highest number, but, after UPA treatment, the frequency in the EAU group decreased significantly (Fig. 6A). Moreover, we observed that the differential number of interactions for the TB, PDC, and mitotic TC subsets from the UPA group decreased prominently (Supplementary Figs. S6A, S6B). Notably, the intensity of intercellular communication increased after the UPA treatment (Fig. 6B). This might be due to the enhanced communication of some cell types, such as BC, CD4, and MYE cells, which accelerated the restoration of the immune system equilibrium (Supplementary Figs. S6C, S6D). We furtherly compared the outgoing and incoming interaction strength in two-dimensional space and found that the cell subpopulations of BCs, CD4 cells, and MYE cells also became the main sources and targets after UPA therapy, indicating its potential role in the recovery from disease processes (Supplementary Fig. S6E).

Figure 6.

Anomalous intercellular communication in EAU attenuated by UPA. (A) Number of inferred interactions among the three groups. (B) Interaction strength among the three groups. (C) The relative information flow of signaling pathway among the control, EAU, and UPA groups. (D) Chord diagrams display the upregulated signaling ligand–receptor pairs of CDLN cells in the EAU and control comparison groups. (E) Chord diagrams display the downregulated signaling ligand–receptor pairs of CDLN cells in the UPA and EAU comparison groups. (F) Chord diagrams display the upregulated signaling ligand–receptor pairs of immune subsets in the EAU and control comparison groups. (G) Chord diagrams display the downregulated signaling ligand–receptor pairs of immune subsets in the UPA and EAU comparison groups. (H) A violin plot is presented to display CXCR4 in immune subsets among the three groups.

To identify and visualize the EAU-specific signaling pathways before and after UPA treatment, we contrasted the sum of communication probability among all pairs of cell groups (the control group with the EAU group and the EAU group with the UPA group) to rank the significant signaling pathways based on the differences in the overall information flow. We discovered that those signaling pathways that were enriched in the EAU group were associated with Thy-1, complement, and migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Meanwhile, the ICOS (Inducible T Cell Costimulator)- and GRN (Granulin Precursor)-related signaling pathways were recovered after UPA treatment (Fig. 6C).

Next, we considered the ligand–receptor pairs that appeared only in the EAU group and not in the control or UPA groups as erased pairs, and functional and pathway enrichment analyses on the erased pairs were performed to further examine the effects of UPA. Functionally, the affected interaction ligand–receptor pairs were highly related to positive regulation of immune response, inflammatory response, and regulation of humoral immune response (Supplementary Figs. S6F, S6G). Furthermore, to explore the changes in immune cells preferably, we established the cell–cell communication networks, and we found that the signaling pathways enriched in MIF, CD74, and CXCR4, were increased by EAU but decreased after UPA disposition (Figs. 6D, 6E). The MIF inhibitor had been identified to reduce the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, an animal model of multiple sclerosis.30 When we analyzed the specific pathway expression during immune cell subsets, we found the identical high expression trend of the CXCR4-mediated migration pathway across the broader and more detailed cell subsets (Figs. 6F–6H). These findings suggest that UPA therapy may play a crucial role in the recovery of EAU by regulating intercellular communication networks primarily through a CXCR4-mediated migration pathway, and CXCR4 may be a potential therapeutic target of AU.

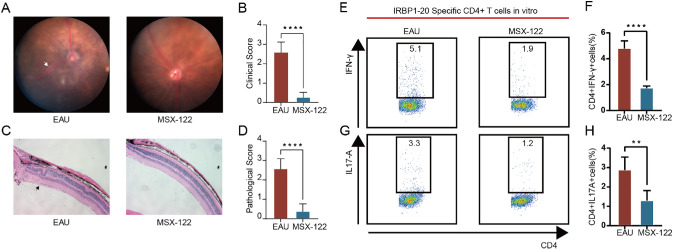

Key Role of CXCR4 in Therapy During EAU

In our investigation of cell–cell communication, we identified the CXCR4-mediated migration pathway as playing a significant role in the pathogenesis of EAU. Notably, CXCR4 has also been implicated in tumor immunology.31 Given the abnormal upregulation of Cxcr4 during EAU (Fig. 4C), we conducted a series of experiments to elucidate its specific role in disease progression. First, we administered the CXCR4 antagonist MSX-122 intraperitoneally to EAU mice. Following treatment with this inhibitor, we observed a marked reduction in EAU symptoms as demonstrated by fundus examination and histopathological analysis (Figs. 7A–7D). To further verify the efficacy of CXCR4 inhibition in EAU, we conducted in vitro experiments using CD4TCs isolated from EAU mice and cultured them with IRBP1–20 in the presence or absence of MSX-122 for 72 hours. Flow cytometry of IRBP1–20-specific CD4TCs demonstrated that MSX-122 treatment reduced the expression of IFN-γ and IL-17A compared to the EAU group (Figs. 7E–7H). These findings suggest that CXCR4 exacerbates EAU via regulation of CD4TC subsets and may represent a potential specific target for the treatment of EAU.

Figure 7.

The key role of CXCR4 in therapy during EAU. (A, B) Day 14 fundus images following immunization in EAU mice and MSX-122–treated mice are presented as representative example (A), with white arrows highlighting the presence of inflammatory exudation and linear lesions. Clinical score of the two groups (n = 5/group) are compared using column charts (B). (C, D) Day 14 H&E-stained images following immunization in EAU mice and MSX-122–-treated mice are presented as representative example (C), with black arrows highlighting retinal folding. Pathological score of the two groups (n = 5/group) are compared using column charts (D). (E–H) Lymphocytes from CDLN cells of EAU mice stimulated by IRBP1–20 with or without MSX-122 for 72 hours. Cells were measured by flow cytometry on the gate of CD4+ T cells. MSX-122 decreased the expression of IFN-γ (E, F) and IL-17A (G, H) (n = 5/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed that aberrant activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway may play a crucial role in the development and progression of uveitis and EAU. By utilizing scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq, we identified the immune cell landscapes and their alterations during disease progression. Our results reveal that treatment with UPA effectively mitigates the onset of EAU and induces changes in the composition of immune cell types and gene expression profiles of relevant immune cells in CDLN. These findings shed light on the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of UPA in terms of specific cell types and gene expression and expand on previous studies that focused on the inhibition of JAK1 protein alone. Additionally, we showed that UPA promotes restoration of the effector T cell (Teff)/Treg imbalance in uveitis while reducing the frequency of ISG15+ CD4TCs, CD8TCs, and BCs in EAU. Furthermore, our results indicate that UPA restores abnormal intercellular communication potentially through targeting CXCR4-mediated migration pathway. Collectively, our findings revealed the rescued characteristics of UPA against multiple immune cell types at both the genetic and cellular levels, providing valuable insights into its potent anti-inflammatory effects and suggesting promising therapeutic strategies for treating uveitis.

JAKs are a family of cytoplasmic non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases consisting of four members, JAK1 to JAK3 and TYK2. These kinases transmit cytokine signaling through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, a fast membrane-to-nucleus signaling module that regulates the transcription and expression of various critical mediators involved in immune responses, cancer development, and inflammatory diseases.32 The downstream effects of JAK/STAT signaling pathway activation are diverse and encompass hematopoiesis, immune fitness, tissue regeneration, inflammation, apoptosis, and adipogenesis.33 Recent investigations have demonstrated that age-associated BCs contribute to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis by inducing the activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs) through TNF-α–mediated ERK1/2 and JAK/STAT1 signaling pathways.34 Conversely, the blockade of ERK1/2 and JAK/STAT1 signaling pathways effectively hinders FLS activation.34

The importance of JAKs in regulating these cellular processes underscores their potential as therapeutic targets for various diseases, including immune-mediated disorders, cancer, and inflammatory conditions. Currently, investigations concerning the JAK/STAT signaling pathway are predominantly carried out using standard RNA-seq methods. However, studies focused on various immune cell types remain insufficiently thorough, and limited attention has been given to scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq. scATAC-seq analysis provides a powerful tool for studying gene regulation at the individual cell level, offering high resolution, efficiency, flexibility, accessibility, and the potential for obtaining novel biological insights, which could be combined with other single-cell omics techniques, such as scRNA-seq, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of gene regulation at the single-cell level. The examination of individual cells at this level of resolution presents a promising avenue for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities inherent in immune cell function and the underlying JAK/STAT signaling pathway mechanisms. Further investigations utilizing single-cell analysis techniques may yield crucial insights into the intricate workings of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and provide valuable contributions to the field of immunology. Our investigation utilizing scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq analysis revealed a heightened JAK/STAT signaling pathway activity in both animal models and patients with VKH disease. Specifically, in EAU, the JAK/STAT signaling pathway exhibited an elevated expression level across all types of immune cells, as well as an increase in the associated gene transcription level. In patients with VKH disease, we observed an elevation in JAK1 locus chromatin accessibility in CD4TCs and the STAT in CD8TCs and BCs. These findings provide further evidence of the critical role played by the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in immune cell function and suggest a potential target for therapeutic intervention in VKH.

UPA is a reversible and selective inhibitor of JAK1 that has been approved for the treatment of numerous autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn's disease.3,5 JAK1 has been shown to be a key factor in several inflammatory signaling pathways. Selective JAK1 inhibitors may be comparable to pan-JAK inhibitors in therapeutic efficacy, with fewer side effects associated with JAK2 or JAK3 blockade.35 The specificity of UPA toward JAK1 provides a targeted approach that allows for more effective management of autoimmune diseases with fewer adverse effects. Therefore, additional research is necessary to evaluate the therapeutic potential of UPA for uveitis management. To investigate the potential therapeutic effect of UPA on uveitis, we applied UPA to the EAU model and studied its underlying therapeutic mechanisms at the single-cell level. Our findings revealed that JAK1 protein expression was increased in the EAU, whereas UPA treatment was able to inhibit its expression. In vivo experiments demonstrated that UPA could alleviate the onset of EAU, possibly by restoring the balance between Teffs and Tregs. Our follow-up experiments confirmed the anti-inflammatory effect of UPA on immune cells during EAU, which prevented the onset of EAU. Furthermore, our results showed that UPA could regulate the composition of immune cells, particularly the balance between Teffs and Tregs, consistent with our flow cytometry results. Notably, we also observed that UPA could rescue the frequency of various immune cells, including CD4NAs, CD8NAs, NBCs, and Tregs, as well as the frequency of ISG15+ CD4 cells, CD8TCs, and BCs. ISG15 is a gene that promotes inflammation, and ISG15+ cells have been reported in various autoimmune diseases.36–38 For example, cell type–specific transcriptional signatures of the proinflammatory monocyte ISG15 were found in VKH syndrome.38 The high frequency of circulating ISG15+ CD8TCs at baseline predicts poor 1-year survival in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis.37 Regarding the rescued gene expression, we found that the rescue effect of UPA mainly focused on down-rescue, and the main responsive cells were CD4TCs, CYTOs, and BCs. Consistently, we also found ISG15 and PIM1 among the down-rescued genes. It has been suggested in previous studies that inhibition of PIM1, as a potential therapeutic target for uveitis, reduces the proportion of Th17 and increases the proportion of Tregs,26 which is consistent with our study. In exploring the effects of UPA on cell subtypes, we found that the gene delivery of UPA was also concentrated in Teffs and Tregs.

Intercellular communication is a crucial modality through which immune cells cooperate synergistically to maintain tissue homeostasis and function. It is widely acknowledged that successful immune surveillance and response necessitate not only the involvement of individual immune cells but also the coordinated actions of an intricate network of cell–cell interactions. Moreover, perturbations in intercellular communication have been linked to various pathological conditions, underlining the importance of this process in maintaining immune system integrity. As such, we characterized communication by ligand–receptor interactions across all cell types in a microenvironment using scRNA-seq to identify and compare the ligand–receptor interactions present in the EAU model. The results of our study suggest that UPA may serve as a significant factor in intercellular communication, particularly in the context of CD4TCs and CYTOs. Additionally, our investigation revealed notable discrepancies in the activation of diverse pathways among the three distinct groups examined. Notably, we observed the activation of a complementary signaling pathway that is specific to EAU, which presents an intriguing avenue for future research. It has long been shown that patients with idiopathic uveitis have elevated serum levels of C3d complement and the circulating immune complex contains complement components.39 The suppression of complement activation by recombinant Crry inhibits experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis.40 These findings reveal that intercellular communication mediated by CXCR4 holds a crucial position in the development of EAU. The study highlights that UPA can act as a significant inhibitor of the CXCR4-mediated migration pathway, in both large and smaller subgroups. The significance of CXCR4 in other autoimmune diseases has been previously acknowledged. For example, the widespread expression of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CX3CR1 in lupus nephritis suggests that they may play a central role in cell transport.41 In the context of early rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis, studies have demonstrated that CCL5+CXCR4 and GZMA+CD8A possess the highest specificity and sensitivity, respectively.42 Our research accentuates the potential application of CXCR4 inhibitors in the treatment of autoimmune disorders and demonstrates that utilization of the CXCR4 inhibitor MSX-122 is a promising strategy to mitigate the progression of EAU. Specifically, we observed a significant reduction in the severity of EAU symptoms along with decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-17A. Our findings suggest that MSX-122 may represent a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of uveitis, highlighting its potential in modulating the immune response in ocular inflammation. However, the present study has several limitations. First, the absence of reports on cases treated with UPA hinders comprehensive evaluation of its effectiveness. Moreover, the lack of available scATAC-seq data during the post-treatment lull period for patients with VKH syndrome poses a gap in our understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, our study presents novel findings regarding the therapeutic effects of UPA on EAU. Our findings revealed upregulation of the JAK1-mediated signaling pathway in both VKH patients and EAU, providing a comprehensive landscape of the immune cells impacted by UPA treatment. Our investigation identified ISG15+ CD4TCs, CD8TCs, and BCs as potentially pathogenic factors involved in the development of uveitis and demonstrated that UPA administration can reduce the frequency of these cells and related gene transcription. Furthermore, our analysis indicates an abnormal elevation in CXCR4-mediated migration pathway in EAU, which may serve as a promising therapeutic target. The present study expands our knowledge of the JAK1-mediated signaling pathway in VKH patients and the pathogenesis of EAU, as well as the immunomodulatory mechanisms of UPA in uveitis. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of uveitis and pave the way for the development of effective therapeutic strategies for this debilitating disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Outstanding Youth Science Fund Project of China (82122016) and Municipal School (Hospital) Jointly Fund Project of Guang Zhou (2023A03J0176).

Disclosure: Z. Huang, None; Q. Jiang, None; J. Chen, None; X. Liu, None; C. Gu, None; T. Tao, None; J. Lv, None; Zhaohuai Li, None; Zuohong Li, None; and W. Su, None

References

- 1. Gritz DC, Wong IG.. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111: 491–500; discussion 500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F, et al.. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018; 391: 2503–2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al.. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384: 1227–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al.. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021; 157: 1047–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boneschansker L, Ananthakrishnan AN. Comparative effectiveness of upadacitinib and tofacitinib in inducing remission in ulcerative colitis: real-world data. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023; 21: 2427–2429.e2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loftus EV Jr, Panés J, Lacerda AP, et al.. Upadacitinib Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023; 388: 1966–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Heijde D, Song IH, Pangan AL, et al.. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019; 394: 2108–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, et al.. Efficacy of upadacitinib in a randomized trial of patients with active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158: 2139–2149.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Loftus EV Jr, et al.. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in a randomized trial of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158: 2123–2138.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rubbert-Roth A, Enejosa J, Pangan AL, et al.. Trial of upadacitinib or abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383: 1511–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fensome A, Ambler CM, Arnold E, et al.. Dual inhibition of TYK2 and JAK1 for the treatment of autoimmune diseases: discovery of ((S)-2,2-difluorocyclopropyl)((1R,5S)-3-(2-((1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-3,8-diazabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-8-yl)methanone (PF-06700841). J Med Chem. 2018; 61: 8597–8612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pietschke K, Holstein J, Meier K, et al.. The inflammation in cutaneous lichen planus is dominated by IFN-γ and IL-21-A basis for therapeutic JAK1 inhibition. Exp Dermatol. 2021; 30: 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, et al.. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell. 2019; 177: 1888–1902.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perng YC, Lenschow DJ.. ISG15 in antiviral immunity and beyond. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018; 16: 423–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, et al.. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001; 131: 647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agarwal RK, Caspi RR.. Rodent models of experimental autoimmune uveitis. Methods Mol Med. 2004; 102: 395–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, et al.. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021; 184: 3573–3587.e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al.. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019; 10: 1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valero-Mora PM. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. J Stat Softw. 2010; 35: 1–3.21603108 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, et al.. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021; 12: 1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stuart T, Srivastava A, Madad S, Lareau CA, Satija R.. Single-cell chromatin state analysis with Signac. Nat Methods. 2021; 18: 1333–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ranzoni AM, Tangherloni A, Berest I, et al.. Integrative single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analysis of human developmental hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2021; 28: 472–487.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N.. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics. 2017; 33: 2938–2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jung YY, Um JY, Sethi G, Ahn KS.. Potential application of leelamine as a novel regulator of chemokine-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23: 9848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Malik MNH, Waqas SF, Zeitvogel J, et al.. Congenital deficiency reveals critical role of ISG15 in skin homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2022; 132: e141573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li H, Xie L, Zhu L, et al.. Multicellular immune dynamics implicate PIM1 as a potential therapeutic target for uveitis. Nat Commun. 2022; 13: 5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al.. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003; 13: 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang S, Luo K, Jiang L, Zhang XD, Lv YH, Li RF.. PCBP1 regulates the transcription and alternative splicing of metastasis-related genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2021; 11: 23356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cao X, Li P, Song X, et al.. PCBP1 is associated with rheumatoid arthritis by affecting RNA products of genes involved in immune response in Th1 cells. Sci Rep. 2022; 12: 8398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kithcart AP, Cox GM, Sielecki T, et al.. A small-molecule inhibitor of macrophage migration inhibitory factor for the treatment of inflammatory disease. FASEB J. 2010; 24: 4459–4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Daniel SK, Seo YD, Pillarisetty VG.. The CXCL12-CXCR4/CXCR7 axis as a mechanism of immune resistance in gastrointestinal malignancies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020; 65: 176–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu X, Li J, Fu M, Zhao X, Wang W.. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021; 6: 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Owen KL, Brockwell NK, Parker BS. JAK-STAT signaling: a double-edged sword of immune regulation and cancer progression. Cancers (Basel). 2019; 11: 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qin Y, Cai ML, Jin HZ, et al.. Age-associated B cells contribute to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis by inducing activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes via TNF-α-mediated ERK1/2 and JAK-STAT1 pathways. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022; 81: 1504–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spinelli FR, Colbert RA, Gadina M.. JAK1: number one in the family; number one in inflammation? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021; 60: ii3–ii10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shen M, Duan C, Xie C, et al.. Identification of key interferon-stimulated genes for indicating the condition of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2022; 13: 962393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ye Y, Chen Z, Jiang S, et al.. Single-cell profiling reveals distinct adaptive immune hallmarks in MDA5+ dermatomyositis with therapeutic implications. Nat Commun. 2022; 13: 6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hu Y, Hu Y, Xiao Y, et al.. Genetic landscape and autoimmunity of monocytes in developing Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020; 117: 25712–25721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vergani S, Di Mauro E, Davies ET, Spinelli D, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D.. Complement activation in uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986; 70: 60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Manickam B, Jha P, Hepburn NJ, et al.. Suppression of complement activation by recombinant Crry inhibits experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis (EAAU). Mol Immunol. 2010; 48: 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arazi A, Rao DA, Berthier CC, et al.. The immune cell landscape in kidneys of patients with lupus nephritis. Nat Immunol. 2019; 20: 902–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou S, Lu H, Xiong M.. Identifying immune cell infiltration and effective diagnostic biomarkers in rheumatoid arthritis by bioinformatics analysis. Front Immunol. 2021; 12: 726747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA data have been deposited at the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) with the project numbers PRJCA016731 and PRJCA004696.