Dear Editor,

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been a worldwide health emergency since January 2020. Vaccinations are currently the most essential strategies for controlling and preventing the pandemic.[1] Various cutaneous adverse effects have been reported in COVID-19-vaccinated patients. COVID-19 vaccinations can cause a cytokine pathway imbalance, which can lead to autoimmunity and autoinflammation.[2]

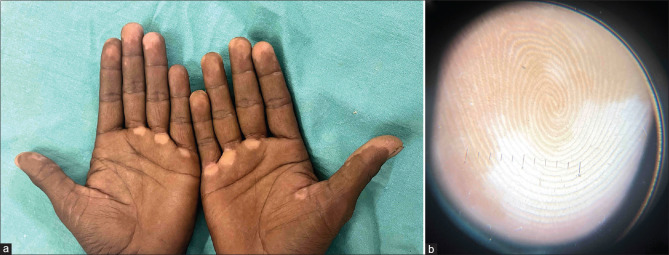

A 41-year-old man presented with a history of new-onset light-colored lesions on the fingertips of bilateral hands and palms, which developed 10 days after receiving the first dose of COVID-19 vaccination (COVAXIN), and the lesions progressed in number and size after receiving the second dose. There was a history of vitiligo in the mother. There was no history of frequent exposures to sanitizers or chemical and physical agents at the workplace or in the environment. His medical history for thyroid disease, autoimmune diseases, and pernicious anemia was unremarkable. No history of any topical or systemic treatment was found. General and systemic examinations were unremarkable. On examination, there were well-demarcated depigmented macules over palms, fingertips, and nail folds [Figures 1a]. Dermoscopy revealed white structureless areas with a glow and the absence of pigment network [Figure 1b]. Based on clinical and dermoscopic findings, a clinical diagnosis of vitiligo was made. The patient was screened for other autoimmune conditions: complete blood count, thyroglobulin, transglutaminase, and thyroid-stimulating hormone, which were within normal ranges. In the absence of any additional risk factors, COVID-19 vaccination was identified as the most likely cause of vitiliginous skin changes. The patient was prescribed a potent topical corticosteroid. The patient is currently under follow-up with no appearance of new lesions.

Figure 1.

(a): Well-demarcated depigmented macules over palms and fingertips on bilateral hands. (b): Dermoscopy revealed white structureless areas with a glow and the absence of pigment network (Heine NC2, 10x)

Vaccinations are generally safe with a low incidence of severe adverse reactions. Cutaneous reactions seen after COVID-19 vaccines are chilblain-like lesions, pityriasis rosea-like eruptions, local injection site reactions, morbilliform eruptions, urticaria, and erythromelalgia. These adverse effects are usually mild and self-limited.[3]

As far as we know, only six cases of vitiligo associated with COVID-19 vaccination are reported in the literature and this is the first due to COVAXIN. Multiple case reports imply a temporal relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and the development of vitiligo-like lesions, according to the literature [Table 1].[1,2,4,5,6,7] The first occurred 1 week after the dose of Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine in a man without a family history of vitiligo who was suffering from ulcerative colitis in 2021.[4] All the case reports suggested that the vitiligo lesions appeared within 1–3 weeks post-vaccination, which was consistent with our case [Table 1].

Table 1.

| Author, year | Age, sex | COVID-19 vaccine | Onset of vitiligo lesions | Sites of lesions | Predisposing factors (personal and family history of autoimmune disorders) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aktas et al.[4] 2021 | 58, male | Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine | One week after the first dose | Face | Patient had a history of ulcerative colitis |

| Kaminetsky et al.[5] 2021 | 61, female | Moderna (mRNA-1273) vaccine | Several days after the first dose, and macules progressed after three days after the second dose | Anterior neck; generalized after the second dose | No predisposing factors |

| Ciccarese et al.[6] 2021 | 33, female | Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine | One week after the first dose | Trunk, neck, and back | Father had vitiligo |

| Uğurer et al.[2] 2022 | 47, male | Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine | One week after the first dose | Bilateral axilla, forearm | History of ankylosing spondylitis |

| Militello et al.[7] 2022 | 67, female | Moderna vaccine | Two weeks after the first dose | Bilateral dorsal hands | No predisposing factors |

| Bukhari et al.[1] 2022 | 13, female | Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine | Three weeks after the first dose | Extremities and trunk | Father and paternal uncle had vitiligo |

The pathophysiology leading to vitiligo after COVID-19 vaccination remains unclear, but several hypotheses exist. Several studies suggest that vaccine components can trigger multiple autoimmune diseases in individuals who are genetically susceptible. Possible pathogenic mechanisms include molecular mimicry and bystander activation. Molecular mimicry occurs when a genetically susceptible individual is vaccinated by the agent that carries antigens that are immunologically similar to host antigens. This leads to the activation of T or B cells. There is a breakdown of tolerance to self-antigens, and an immune response is directed towards host antigens. Bystander activation occurs when viral agents induce the release of sequestered self-antigens or modify self-antigens that activate antigen-presenting cells, leading to the clonal expansion of self-reactive T and B cells.[1,6]

Vaccine components may trigger a strong innate immune response, resulting in nonspecific activation of cluster of differentiation (CD)4+ or CD8+ T cells, causing adverse drug reactions. Another possible mechanism is vaccine-induced stimulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) that secrete type 1 interferon (IFN-1).[1,8] IFN-1 production and pDC recruitment are an important step in vitiligo pathogenesis.[9,10] Through all these proposed mechanisms, the vaccine may stimulate the immune system to produce antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein and incidentally against melanocytes, which may become unintentional targets for antibodies and immune cells newly produced by the vaccine. These hypotheses may be plausible because vitiligo involves the destruction of melanocytes by autoreactive CD8+ T cells and successful vaccination also involves an extensive CD8+ T-cell response.[5]

Clinicians should be aware of these autoimmune cutaneous adverse reactions to vaccinations. Such adverse reactions are modest and manageable and possess a low risk compared with the deadly outcome of COVID-19 infection; thus, patients need to be encouraged to continue receiving vaccinations. In conclusion, this is the first case of vitiligo reported to develop after COVAXIN vaccination. We present this case to add to the mounting literature regarding COVID-19 vaccination, which may assist clinicians regarding the spectrum of possible cutaneous manifestations. This may also assist others to be vigilant of the association between COVID-19 vaccination and vitiligo. Thus, further and extensive case studies are needed to demonstrate a causal relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and vitiligo.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bukhari AE. New-onset of vitiligo in a child following COVID-19 vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:68–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uğurer E, Sivaz O, KıvançAltunay İ. Newly-developed vitiligo following COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1350–1. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, Lipoff JB, Moustafa D, Tyagi A, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: A registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aktas H, Ertuğrul G. Vitiligo in a COVID-19-vaccinated patient with ulcerative colitis: Coincidence? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:143–4. doi: 10.1111/ced.14842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminetsky J, Rudikoff D. New-onset vitiligo following mRNA-1273 (Moderna) COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04865. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciccarese G, Drago F, Boldrin S, Pattaro M, Parodi A. Sudden onset of vitiligo after COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15196. doi: 10.1111/dth.15196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Militello M, Ambur AB, Steffes W. Vitiligo possibly triggered by COVID-19 vaccination. Cureus. 2022;14:e20902. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdullah L, Awada B, Kurban M, Abbas O. Comment on ‘Vitiligo in a COVID-19-vaccinated patient with ulcerative colitis: Coincidence?’ Type I interferons as possible link between COVID-19 vaccine and vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:436–7. doi: 10.1111/ced.14932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertolotti A, Boniface K, Vergier B, Mossalayi D, Taieb A, Ezzedine K, et al. Type I interferon signature in the initiation of the immune response in vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:398–407. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertolani M, Rodighiero E, Del Giudice MB, Lotti T, Feliciani C, Satolli F. Vitiligo: What's old, what's new. Dermatol Rep. 2021;13:9142. doi: 10.4081/dr.2021.9142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]