Abstract

Indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA) staining methods with Ehrlichia equi (MRK or BDS strains) and Western blot analyses containing a human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) agent (NCH-1 strain) were used to confirm probable human cases of infection in Connecticut during 1995 and 1996. Also included were other tests for Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), Babesia microti, and Borrelia burgdorferi. Thirty-three (8.8%) of 375 patients who had fever accompanied by marked leukopenia or thrombocytopenia were serologically confirmed as having HGE. Western blot analyses of a subset of positive sera confirmed the results of the IFA staining methods for 15 (78.9%) of 19 seropositive specimens obtained from different persons. There was frequent detection of antibodies to a 44-kDa protein of the HGE agent. Serologic testing also revealed possible cases of Lyme borreliosis (n = 142), babesiosis (n = 41), and HME (n = 21). Forty-seven (26.1%) of 180 patients had antibodies to two or more tick-borne agents. Therefore, when one of these diseases is clinically suspected or diagnosed, clinicians should consider the possibility of other current or past tick-borne infections.

Ticks are abundant in or near forested areas of southern New England. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE), a recently described tick-associated disease, occurs there and in the upper midwestern United States (29). Illnesses can be mild or severe. In patients with severe illness, there is usually marked thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevations in serum aminotransferase concentrations (4, 28). Although infections can sometimes be fatal (4, 28, 29), prompt clinical diagnosis and antibiotic therapy effectively reduce morbidity and mortality.

The etiologic agent of HGE (an unnamed organism) in the United States is very closely related, with at least 99.8% homology (5), to Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila, veterinary pathogens widely distributed in the United States and Europe. On the basis of 16S rRNA gene analyses (5, 6, 29), E. equi and E. phagocytophila are nearly identical (99.8% homology); these organisms and the HGE agent are considered to be members of the E. phagocytophila genogroup. The suspected tick vectors of the HGE agent are Ixodes scapularis in the eastern and upper midwestern United States and Ixodes pacificus in western states (29). Ixodes ricinus, a closely related tick species, transmits E. phagocytophila, the causative agent of tick-borne fever in cattle and sheep in Europe. Following the application of PCR methods, the DNA of the HGE agent has been detected in I. scapularis ticks in Connecticut (19), Massachusetts (27), Rhode Island (31), and Wisconsin (23). Moreover, clinical and serological findings indicate that HGE occurs in areas where these ticks and infections of human babesiosis and Lyme borreliosis have been reported (12, 17, 27, 28, 30). There is growing evidence of human exposure to multiple tick-borne pathogens in areas where I. scapularis ticks abound.

Indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA) staining methods are being used extensively to detect antibodies to the HGE agent. However, little is known about the accuracy of these procedures or the prevalence of infection with or without the presence of other tick-borne pathogens, such as Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Babesia microti. The present study was conducted to (i) analyze sera from persons who were strongly suspected by physicians as having HGE and to determine the prevalence of infection, (ii) compare the results of IFA staining methods with those of Western blot analysis for the detection of antibodies to E. equi and the HGE agent, respectively, and (iii) determine if sera positive for HGE antibodies also contain immunoglobulins to E. chaffeensis, B. burgdorferi, and B. microti.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum specimens.

As a part of a statewide surveillance program on emerging infectious diseases, physicians obtained 512 serum specimens from 375 persons who lived in or who had entered tick-infested areas of Connecticut and who had acute febrile illnesses with headache and myalgias. Accompanying clinical records indicated leukopenia or thrombocytopenia for all subjects. Therefore, all sera were from patients who were clinically suspected of having HGE. Sera were obtained 5 to 515 days after the onset of illness during 1995 and 1996. There were 254 samples from 117 persons available for determination of changes in antibody titers (i.e., seroconversions and reversions). Specimens were sent from the Connecticut Department of Health to the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station for analyses.

Serologic testing for HGE.

IFA staining methods and Western blot analysis were used to detect total or class-specific immunoglobulins to E. equi and the HGE agent, respectively. The former has been successfully used as a surrogate antigen for the laboratory diagnosis of HGE (4, 6, 30). The antigen-coated slides used in IFA assays were purchased from John Madigan of the University of California (Davis, Calif.) and contained horse neutrophils infected with E. equi (the MRK or BDS strain). Sera were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solutions (pH 7.2) and were tested for total antibodies with a 1:80 dilution of polyvalent fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-human immunoglobulin (Ig) (Organon Teknika Corp., Durham, N.C.). To detect class-specific antibodies, commercially prepared goat anti-human IgM (μ-chain-specific) and goat anti-human IgG (γ-chain-specific) reagents (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) were diluted in PBS solutions to 1:40 and 1:20, respectively. The reactivities of these conjugates were verified by testing a panel of control sera from persons who had Lyme borreliosis and in whom immunoblotting or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedures had confirmed the presence of IgM or IgG antibodies. Further details on IFA staining methods and sources of positive and negative control sera for HGE are reported elsewhere (17). Distinct fluorescence of inclusion bodies (morulae) in infected neutrophils was considered evidence of antibody presence in sera diluted to 1:80 or greater. There were no false-positive reactions when sera from healthy persons (i.e., negative controls) were tested at this dilution. Grading of fluorescence was done conservatively. Serial dilutions of all positive sera were retested to determine titration endpoints.

The procedures used in the Western blot analysis to detect total antibodies have been described previously (11). Briefly, HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia) cells were used to cultivate the NCH-1 strain of the HGE agent, originally isolated from a human in Nantucket, Mass. (27). Lysates (5 to 10 μg of total protein) of infected or uninfected (i.e., control) cells were dissolved in sample buffer (5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.8% bromophenol blue in 6.25 mM Tris buffer [pH 6.8]) before heating at 100°C for 10 min. Blocking solutions consisted of PBS with 5% nonfat dry milk. The commercially prepared conjugate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) used was a 1:1,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-labeled F(ab′)2 anti-human Ig. Human sera were diluted to 1:100 in PBS solution with 5% bovine serum albumin and were tested in parallel against both lysate preparations of proteins that had been transferred to nitrocellulose sheets. All strips were washed three times with PBS solutions containing 0.2% Tween at each of the required steps following incubation periods. Blots were developed for 5 min in nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Stratagene, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.), and the reaction was quenched in distilled water. Immunoblotting procedures included molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) and the positive and negative serum controls used in an earlier investigation (11).

Serologic testing for babesiosis and Lyme borreliosis.

An IFA staining procedure (17) was used to detect total antibodies to B. microti, while polyvalent and class-specific ELISAs were used to quantitate the concentrations of antibodies to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (strain 2591) in serum. Whole cells of this spirochete were coated onto polystyrene plates for a polyvalent ELISA used for the screening of sera. Purified preparations of the following recombinant antigens of B. burgdorferi were used to confirm polyvalent assay results and to detect IgM or IgG antibodies: outer surface protein (Osp) OspC, OspE, OspF, and p41-G (the 13-kDa central fragment of flagellin). When available, paired sera were analyzed to document seroconversions and reversions. Details on the production of antigens, sources of conjugates and control sera, and the sensitivities and specificities of these assays have been reported previously (14, 15, 17, 18).

Specificity tests.

Tests on the specificity of the IFA staining methods have been conducted with homologous and heterologous antigens and antisera of ehrlichiae, such as E. canis, E. chaffeensis, E. equi, and E. risticii (17, 19). Although there was no evidence of cross-reactivity between E. equi and E. chaffeensis in these tests and there are no reports of the DNA of the latter being detected in human or tick tissues in Connecticut, all sera were tested by IFA staining methods for E. chaffeensis antibodies as done before (17). Further analyses of human sera were needed to determine if the banding patterns associated with B. burgdorferi infections in immunoblots overlap with those characteristic of HGE. A peptide of E. equi and isolates of the HGE agent with a molecular mass of about 44 kDa appears to be a suitable indicator of HGE infection (6, 10, 11, 24, 29) because it is frequently reactive in Western blot analysis and has a high degree of specificity. Accordingly, five coded serum specimens from persons who had erythema migrans and IgM and IgG antibodies to whole B. burgdorferi cells (14) were screened by immunoblotting methods with lysates of the NCH-1 strain of the HGE agent. These patients had no history of leukopenia or thrombocytopenia, and their sera were negative by IFA staining methods for antibodies to E. equi. In addition, five serum specimens from syphilitic patients and five serum specimens from persons diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, which had been tested in another study (14), were included in the analyses to assess specificity.

RESULTS

There were antibodies to E. equi in 50 (9.8%) of 512 serum specimens tested by IFA staining methods. The titration endpoints ranged from 1:80 to 1:5,120 (Table 1). A comparison of geometric means revealed at least a threefold higher value for sera tested by an ELISA for Lyme borreliosis compared to those calculated for HGE, human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), and babesiosis by IFA staining methods.

TABLE 1.

Reactivities to E. equi, E. chaffeensis, B. microti, and B. burgdorferi for persons who had leukopenia or thrombocytopenia and whose sera were collected in Connecticut during 1995 and 1996

| Antigen tested | Polyvalent assay method | Total no. of serum specimens analyzeda | No. (%) of serum specimens positive | Antibody titer

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric mean | Range | ||||

| E. equi | IFA | 512 | 50 (9.8) | 307 | 80–5,120 |

| E. chaffeensis | IFA | 512 | 30 (5.9) | 180 | 80–2,560 |

| B. microti | IFA | 494 | 47 (9.5) | 212 | 80–5,120 |

| B. burgdorferi | ELISA | 512 | 184 (36) | 958 | 160–40,960 |

There were 375 patients in the study group. Multiple serum samples (n = 254) were available from 117 of these subjects for analyses by IFA staining methods and ELISAs.

Serologic results (Table 2) indicated more cases of Lyme borreliosis (n = 142) than babesiosis (n = 41), HGE (n = 33), or HME (n = 21). The age distribution for all 375 patients was 2 to 96 years, whereas the ages of persons confirmed to have HGE ranged from 16 to 81 years. The median ages for each group were 53 and 48 years, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of human infections on the basis of testing for total antibodies to multiple tick-borne pathogens

| Antigen(s)a | No. of probable cases of infection | % Seropositive patientsb |

|---|---|---|

| E. equi | 11 | 6.1 |

| E. chaf. | 7 | 3.9 |

| E. chaf., E. equi | 3 | 1.7 |

| E. chaf., E. equi, B. burg. | 5 | 2.8 |

| E. chaf., E. equi, B. mic. | 1 | 0.6 |

| E. chaf., B. burg., B. mic. | 2 | 1.1 |

| E. chaf., B. burg. | 2 | 1.1 |

| E. chaf., B. mic. | 1 | 0.6 |

| E. equi, B. mic. | 1 | 0.6 |

| E. equi, B. burg. | 10 | 5.6 |

| E. equi, B. burg., B. mic. | 2 | 1.1 |

| B. mic. | 14 | 7.8 |

| B. mic., B. burg. | 20 | 11.1 |

| B. burg. | 101 | 56.1 |

E. chaf., E. chaffeensis; B. burg., B. burgdorferi; B. mic., B. microti.

There were 180 persons who had antibodies to one or more tick-borne pathogens.

Forty-seven (26.1%) of 180 seropositive patients had antibodies to two or more tick-borne agents. Exposure to B. microti and B. burgdorferi (n = 20 persons) was most prevalent, followed by dual infections with E. equi and B. burgdorferi (n = 10). Nine persons produced antibodies to E. equi and E. chaffeensis alone or in combination with either B. burgdorferi or B. microti. Titers to the ehrlichiae were 2- to 64-fold higher than those to B. microti or B. burgdorferi in six subjects. There was no difference in titers for two persons who had antibodies to E. equi and E. chaffeensis. However, sera from another patient had E. chaffeensis-reactive antibodies at 8- to 16-fold higher concentrations (titers, 1:640 and 1:1,280) than to E. equi (titer, 1:80). There was evidence of single infections in 133 patients, but no persons had antibodies to all four pathogens. Those who had been exposed to multiple agents lived in towns located mainly in southern Connecticut, areas where I. scapularis ticks are most abundant.

Antibodies to B. burgdorferi were present along with those to E. equi or B. microti, or both. Forty serum specimens from this group were selected to be tested by a polyvalent ELISA for reactivity to OspC, OspE, and OspF of B. burgdorferi. Twenty-eight samples (70%) reacted positively to one or more of these highly specific recombinant antigens. Seropositivity was nearly twofold higher than the seropositivities recorded for 15 of 37 serum samples (40.5% positivity) selected from a group of 138 specimens that had antibodies only to whole B. burgdorferi cells. Seropositivities for antibodies to OspC (40.5 to 70% positivity) greatly exceeded seropositivities for antibodies to OspF (2.7 to 17.5% positivity) for both test groups. Titration endpoints ranged from 1:160 to 1:40,960 and from 1:160 to 1:5,120 for serum samples seropositive for antibodies to OspC and OspF, respectively. There were no positive reactions for antibodies to OspE in either group of sera.

In analyses of paired sera, 38 seroconversions and 14 reversions were recorded. Fourfold or greater rises in titration endpoints were noted for 19 patients with Lyme borreliosis. Fewer seroconversions were recorded for patients with HGE (n = 12) and babesiosis (n = 7). Changes in antibody titers occurred in 5 to 53 days for patients with HGE infections, 5 to 161 days for patients with Lyme borreliosis, and 33 to 56 days for patients with babesiosis. Reversions in serologic reactivity occurred in 21 to 271 days for four HGE patients, whereas serologic reactivity occurred in 4 to 131 days for five patients with Lyme borreliosis and 18 to 148 days for four patients with babesiosis. The greatest rise in total antibody titers (negative to 1:20,480) occurred in two patients with Lyme borreliosis in 15 and 19 days, while the greatest decline in antibody titer (1:1,280 to negative) was recorded for a patient with B. burgdorferi infection in 75 days. Records on antibiotic treatment relative to the times that blood samples were collected were incomplete or unavailable.

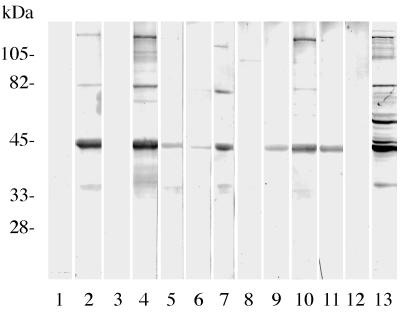

Western blot analyses were conducted to assess the accuracy of IFA staining methods for the detection of HGE infections. Of the 19 serum specimens from 19 patients confirmed as having HGE by IFA staining procedures, 15 (78.9%) serum specimens had antibodies that reacted with the 44-kDa protein of the HGE agent in immunoblots (Fig. 1). Two additional positive control serum samples were reactive in both assays. There was no reactivity to uninfected HL-60 cells (negative controls). Furthermore, immunoblots revealed no antibodies to the HGE agent in 30 (96.8%) of 31 serum samples found to be negative by IFA staining methods. This group included sera from persons who had rheumatoid arthritis, syphilis, or Lyme borreliosis. A serum sample from a patient who had Lyme borreliosis was negative by IFA staining methods with the BDS strain of E. equi but was positive by immunoblotting (44-kDa band only) with the NCH-1 strain of the HGE agent. When retested by IFA staining methods with the NCH-1 strain, the results were negative, suggesting that the differences are due to experimental techniques rather than antigenic variation. A sufficient amount of serum was available for further testing of one of the four samples found to be positive by IFA staining with the BDS strain and negative by immunoblotting with the NCH-1 strain (Fig. 1, lane 8). When the latter strain was included in tests performed by IFA staining methods, the sample was positive for antibodies at a titer of 1:160, again indicating differences due to methodologies.

FIG. 1.

Representative immunoblots of individual human serum specimens, obtained in Connecticut during 1995 and 1996, showing variations in total antibody responses to lysates of the NCH-1 strain of the HGE organism. Molecular masses are indicated in kilodaltons. Lanes 2, 4 to 7, and 9 to 11, reactivities of seropositive specimens. Protein antigen with a molecular mass of about 44 kDa was frequently reactive. The sample in lane 8 shows a single weak band at about 100 kDa, but the sample was recorded as negative. The human serum samples in lanes 1, 3, and 12 show no reactivity. Lane 13, a positive control for HGE.

Serologic analyses for class-specific IgM and IgG antibodies to E. equi and B. burgdorferi revealed differences in seropositivity. We tested at least 24 specimens from individuals in each of three study groups in which persons had leukopenia (1.0 × 109 to 4.0 × 109/liter) or thrombocytopenia (9.0 × 109 to 148 × 109/liter), or both disorders (Table 3). In tests for E. equi antibodies, 3 (1.2%) of 250 serum samples from persons who had low leukocyte and platelet counts had IgM antibodies. Human IgG antibodies were detected in sera from each study group. The proportions ranged from 2.5 to 10.9%. In serologic analyses for Lyme borreliosis, relatively higher numbers of serum samples contained IgM antibodies; the values ranged from 67.6 to 82.1%. Similarly, the proportions of seropositive specimens with IgG antibodies were high (57.8 to 75%).

TABLE 3.

Numbers of human serum samples with IgM and IgG antibodies to E. equi and B. burgdorferi

| Study groupa |

E. equi

|

B. burgdorferi

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM

|

IgG

|

IgM

|

IgG

|

|||||

| Total no. of serum samples tested | No. (%) positive | Total no. of serum samples tested | No. (%) positive | Total no. of serum samples tested | No. (%) positive | Total no. of serum samples tested | No. (%) positive | |

| A | 80 | 0 | 80 | 2 (3) | 24 | 16 (67) | 24 | 18 (75) |

| B | 100 | 0 | 101 | 11 (11) | 39 | 32 (82) | 39 | 24 (62) |

| C | 250 | 3 (1) | 252 | 18 (7) | 71 | 48 (68) | 71 | 41 (58) |

Study groups: A, patients with leukopenia; B, patients with thrombocytopenia; and C, patients with leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Note that class-specific antibodies to E. equi and whole B. burgdorferi cells were detected by IFA staining methods and ELISAs, respectively. Persons were suspected of having granulocytic ehrlichiosis and not Lyme borreliosis.

In separate analyses, sera containing IgM or IgG antibodies to whole B. burgdorferi cells were retested by ELISAs containing recombinant antigens of this bacterium. Sera in each study group had class-specific antibodies to one or more Osps or p41-G (Table 4). The proportions of positive serum samples ranged from 46.7 to 67.7% when samples were screened for IgM antibodies to OspC. In analyses for IgG antibodies, seroreactivity to this recombinant antigen was likewise recorded in each of the three study groups; the proportions of positive sera ranged from 31.3 to 63.6%. There was evidence of IgM or IgG antibodies to OspE, OspF, and p41-G, but the rate of seropositivity was usually less than that noted for antibodies to OspC.

TABLE 4.

Reactivities of sera from persons suspected of having granulocytic ehrlichiosis to whole cells and recombinant antigens of B. burgdorferi in class-specific ELISAs

| Study groupa | No. of serum samples positive for the following antibodies to the indicated protein:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM

|

IgG

|

|||||||||

| Whole cell | OspC | OspE | OspF | p41-G | Whole cell | OspC | OspE | OspF | p41-G | |

| A | 15 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| B | 31 | 21 | 3 | 9 | 14 | 22 | 14 | 1 | 12 | 8 |

| C | 44 | 29 | 6 | 11 | 27 | 36 | 17 | 0 | 18 | 9 |

| Total | 90 | 57 | 9 | 22 | 49 | 74 | 36 | 1 | 34 | 19 |

See footnote a of Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Serologic analyses provided evidence of HGE and HME in Connecticut. However, when considering that all persons had marked leukopenia or thrombocytopenia, the prevalence of human ehrlichiosis was relatively low. The putative tick vector of the HGE agent, I. scapularis, is found throughout most of Connecticut. By using PCR procedures, 50% of the 118 female I. scapularis ticks from southern Connecticut analyzed carried the DNA of the HGE agent (19). An infection rate of 53% was recorded for female I. scapularis ticks in Westchester County, N.Y. (25), but lower rates (10 to 15%) were reported for Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin (23, 27, 31). Similar DNA analyses revealed no evidence of E. chaffeensis in Connecticut ticks (19). On the basis of the relatively low number of serologically confirmed HGE cases, it appears that the tick transmission rate for this pathogen is low in Connecticut. We also suspect that most persons in the present study probably had other disorders unrelated to tick bites and note that patients who have Lyme borreliosis rarely present with leukopenia or thrombocytopenia. Nonetheless, our results on granulocytic ehrlichiosis agree with those reported earlier, which documented this disease in humans and horses in Connecticut (8, 9, 13).

Although physicians suspected HGE, there was serologic evidence of HME, Lyme borreliosis, and babesiosis in some patients. It is possible that E. chaffeensis infects persons in the northeastern United States, but well-documented cases with supportive results from culture or PCR analyses are lacking there. This disease occurs more frequently in the southern United States, where the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is abundant (28, 29). As observed before (17, 22), some serum samples contained antibodies to E. equi and E. chaffeensis. In our experience (17), there was little or no cross-reactivity between these organisms or with B. microti and B. burgdorferi. Furthermore, sera from 133 (73.9%) of 180 seropositive patients in the present study contained antibodies to a single organism, and sera from persons who had syphilis, rheumatoid arthritis, or babesiosis did not cross-react in tests for HGE. We recognize that persons who had antibodies to E. chaffeensis could have been infected in other states. Future studies should focus on the isolation and identification of ehrlichiae from ticks and wild mammals to determine if E. chaffeensis occurs in New England and if there are other unknown pathogens that might share antigens with the HGE agent and E. chaffeensis. Illnesses in patients who had antibodies to B. burgdorferi and B. microti were probably undiagnosed in many instances. Also, subclinical forms of Lyme borreliosis and babesiosis have been reported (7, 12, 26). It is unclear if persons who had antibodies to these unrelated pathogens had concurrent infections or if they had been exposed to different organisms over extended periods of time. More precise case history information, including isolation data, is needed to verify multiple, active tick-borne infections (21).

Culturing of blood and other tissues from field-collected animals has demonstrated simultaneous infections with B. burgdorferi and B. microti in white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) in areas of Connecticut and Rhode Island where I. scapularis abounds (1, 2). Human beings have been infected with B. microti in inland areas of Connecticut (2). In addition, analyses of sera from humans (17, 20) and white-footed mice (16) revealed coexisting antibodies to multiple agents, including the HGE organism. Simultaneous human Lyme borreliosis and granulocytic ehrlichiosis infections have been demonstrated by culture methods in Westchester County, N.Y. (21). Therefore, if one of these diseases is suspected or diagnosed in humans, serologic testing and the use of adjunct laboratory procedures (i.e., examination of stained leukocytes or erythrocytes, culture for the detection of pathogens, or testing for the DNA of the agents) are warranted. Concurrent infections with different pathogens may complicate illnesses, and consequently, the clinical presentation (signs and symptoms) may be unusual for some patients. Finally, knowledge of simultaneous babesiosis and Lyme borreliosis is important for treatment because different antibiotics are required (28, 29).

Class-specific analyses detected IgM and IgG antibodies to E. equi and B. burgdorferi. However, far fewer patients with suspected HGE infections than patients with Lyme borreliosis were seropositive for IgM antibody. As a part of our study of HGE, physicians were required to submit clinical data that indicated whether the patients had leukopenia and/or thrombocytopenia. Consequently, most of the blood samples were collected later in the course of the disease when IgG antibodies were more likely to be present. The detection of IgM antibodies to B. burgdorferi most likely indicates early stages of infection. Documentation of seroconversions for HGE and Lyme borreliosis was especially important because the clinical picture was often unclear for many patients.

Results of Western blot analyses compared favorably with those obtained by IFA staining methods. We attribute the low number of discrepant results to differences in assay sensitivities. We also recognize, however, that serologic results may occasionally vary with the strain of antigen used in the tests. Antigenic diversity occurs among different strains of the HGE agent (3, 33). Nonetheless, the visualization of key banding patterns for proteins with molecular masses of about 40 to 44 kDa was very helpful in our serological confirmation of HGE. Previous investigators have reported on the significance of the 44-kDa immunodominant protein as a highly specific serologic indicator (6, 11, 24, 29) and on other less frequently identified HGE antigens of 40, 65, 80, and greater than 100 kDa (11). As in the laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis, Western blot analyses can be used to confirm less specific prescreening tests for antibodies to the HGE agent (24). However, additional work is needed to identify other specific proteins and to produce the appropriate monoclonal antibodies so that immunoblotting results for HGE infections can be further validated and standardized.

As in studies of Lyme borreliosis (18), the production of purified, recombinant fusion proteins of the HGE agent might improve the sensitivities and specificities of ELISAs and Western blotting. Our inclusion of highly specific OspC, p41-G, and OspF antigens in ELISAs for Lyme borreliosis was particularly useful in confirming the results of a polyvalent ELISA, which contained whole-cell antigen of B. burgdorferi. The 44-kDa major outer membrane protein of the HGE agent has recently been cloned and expressed (10, 32). Preliminary test results for a limited number of sera indicate high degrees of sensitivity and specificity in a dot blot immunoassay and Western blot analysis, but further evaluations are needed, however, with a larger panel of serum specimens to assess assay performance. Standardization of highly sensitive and specific class-specific ELISAs for HGE would be easier than standardization of IFA staining methods, and with automation, class-specific ELISAs would be more cost-effective than Western blot analyses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tia Blevins, Bonnie Hamid, Manchuan Chen, and Hong Tao for assistance with the preparation of antigens and performance of the analyses and are grateful to James Meek of Yale University and to James L. Hadler, Matthew L. Cartter, and Elizabeth Hilborn of the Connecticut State Health Department for initiating and coordinating an emerging infectious disease program.

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention including the Emerging Infections Program (grants CCU 111188-02, CCU-106581, and HR8/CCH113382-01), the National Institutes of Health (grants PO-1-AI-30548 and AI-49988), the Mathers Foundation, the Arthritis Foundation, and the American Heart Association; federal funds allocated from the Hatch Act; and funds from the State of Connecticut (Charles Goodyear Award). Erol Fikrig is a Pew Scholar, and Richard A. Flavell is an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Jacob W. IJdo is a Daland Fellow of the American Philosophical Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson J F, Johnson R C, Magnarelli L A, Hyde F W, Myers J E. Peromyscus leucopus and Microtus pennsylvanicus simultaneously infected with Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:135–137. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.1.135-137.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J F, Mintz E D, Gadbaw J J, Magnarelli L A. Babesia microti, human babesiosis, and Borrelia burgdorferi in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2779–2783. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2779-2783.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asanovich K M, Bakken J S, Madigan J F, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Wormser G P, Dumler J S. Antigenic diversity of granulocytic Ehrlichia isolates from humans in Wisconsin and New York and a horse in California. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1029–1034. doi: 10.1086/516529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Wilson-Nordskog C, Tilden R L, Asanovich K, Dumler J S. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 1996;275:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S-M, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Walker D H. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.589-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumler J S, Asanovich K M, Bakken J S, Richter P, Kimsey R, Madigan J E. Serologic cross-reactions among Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia phagocytophila, and human granulocytic ehrlichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1098–1103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1098-1103.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanrahan J P, Benach J L, Coleman J L, Bosler E M, Morse D L, Cameron D J, Edelman R, Kaslow R A. Incidence and cumulative frequency of endemic Lyme disease in a community. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:489–496. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardalo C J, Quagliarello V, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Connecticut: report of a fatal case. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:910–914. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heimer R, Van Andel A, Wormser G P, Wilson M L. Propagation of granulocytic Ehrlichia spp. from human and equine sources in HL-60 cells induced to differentiate into functional granulocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:923–927. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.923-927.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IJdo, J. W., W. Sun, Y. Zhang, L. A. Magnarelli, and E. Fikrig. Cloning of the gene encoding the 44-kilodalton antigen of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and characterization of the humoral response. Infect. Immun. 66:3264–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.IJdo J W, Zhang Y, Hodzic E, Magnarelli L A, Wilson M L, Telford III S R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. The early humoral response in human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:687–692. doi: 10.1086/514091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause P J, Telford III S R, Ryan R, Hurta A B, Kwasnik I, Luger S, Niederman J, Gerber M, Spielman A. Geographical and temporal distribution of babesial infection in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.1-4.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madigan J E, Barlough J E, Dumler J S. Equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Connecticut caused by an agent resembling the human granulocytic ehrlichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:434–435. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.434-435.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnarelli L A, Anderson J F. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for the detection of class-specific immunoglobulins to Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:818–825. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnarelli L A, Anderson J F, Johnson R C. Cross-reactivity in serological tests for Lyme disease and other spirochetal infections. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:183–188. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnarelli L A, Anderson J F, Stafford III K C, Dumler J S. Antibodies to multiple tick-borne pathogens of babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme borreliosis in white-footed mice. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33:466–473. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-33.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnarelli L A, Dumler J S, Anderson J F, Johnson R C, Fikrig E. Coexistence of antibodies to tick-borne pathogens of babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme borreliosis in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3054–3057. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3054-3057.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E, Padula S J, Anderson J F, Flavell R A. Use of recombinant antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi in serologic tests for diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:237–240. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.237-240.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnarelli L A, Stafford III K C, Mather T N, Yeh M-T, Horn K D, Dumler J S. Hemocytic rickettsia-like organisms in ticks: serologic reactivity with antisera to ehrlichiae and detection of DNA of agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2710–2714. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2710-2714.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Hofkes J M. Immunoserologic evidence of coinfection with B. burgdorferi, B. microti, and human granulocytic Ehrlichia species in residents of Wisconsin and Minnesota. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:44–48. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.724-727.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadelman R B, Horowitz H W, Hsieh T-C, Wu J M, Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Schwartz I, Nowakowski J, Varde S, Wormser G P. Simultaneous human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and Lyme borreliosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:27–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707033370105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson W L, Comer J A, Sumner J W, Gingrich-Baker C, Coughlin R T, Magnarelli L A, Olson J G, Childs J E. An indirect immunofluorescence assay using a cell culture-derived antigen for detection of antibodies to the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1510–1516. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1510-1516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pancholi P, Kolbert C P, Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Telford III S R, Persing D H. Ixodes dammini as a potential vector of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1007–1012. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravyn M D, Goodman J L, Kodner C B, Westad D K, Coleman L A, Engstrom S M, Nelson C M, Johnson R C. Immunodiagnosis of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by using culture-derived human isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1480–1488. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1480-1488.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz I, Fish D, Daniels T J. Prevalence of the rickettsial agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in ticks from a hyperendemic focus of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:49–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707033370111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steere A C, Taylor E, Wilson M L, Levine J F, Spielman A. Longitudinal assessment of the clinical and epidemiological features of Lyme disease in a defined population. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:295–300. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telford S R, III, Dawson J E, Katavolos P, Warner C K, Kolbert C P, Persing D H. Perpetuation of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a deer tick-rodent cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6209–6214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker D H, Barbour A G, Oliver J H, Lane R S, Dumler J S, Dennis D T, Persing D H, Azad A F, McSweegan E. Emerging bacterial zoonotic and vector-borne diseases: ecological and epidemiological factors. JAMA. 1996;275:463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker D H, Dumler J S. Emergence of the ehrlichioses as human health problems. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:18–29. doi: 10.3201/eid0201.960102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong S J, Brady G S, Dumler J S. Serological responses to Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and Borrelia burgdorferi in patients from New York State. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2198–2205. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2198-2205.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh M-T, Mather T N, Coughlin R T, Gingrich-Baker C, Sumner J W, Massung R F. Serologic and molecular detection of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Rhode Island. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:944–947. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.944-947.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, Hechemy K. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1666–1673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1666-1673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhi N, Rikihisa Y, Kim H Y, Wormser G P, Horowitz H W. Comparison of major antigenic proteins of six strains of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent by Western immunoblot analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2606–2611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2606-2611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]