Summary

Large GWAS indicated that genetic factors influence the response to SARS-CoV-2. However, sex, age, concomitant diseases, differences in ancestry, and uneven exposure to the virus impacted the interpretation of data. We aimed to perform a GWAS of COVID-19 outcome in a homogeneous population who experienced a high exposure to the virus and with a known infection status. We recruited inhabitants of Bergamo province—that in spring 2020 was the epicenter of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic in Europe—via an online questionnaire followed by personal interviews. Cases and controls were matched by age, sex and risk factors. We genotyped 1195 individuals and replicated the association at the 3p21.31 locus with severity, but with a stronger effect size that further increased in gravely ill patients. Transcriptome-wide association study highlighted eQTLs for LZTFL1 and CCR9. We also identified 17 loci not previously reported, suggestive for an association with either COVID-19 severity or susceptibility.

Subject areas: Respiratory medicine, Public health, Virology, Genomics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The Neanderthal haplotype is the major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19

-

•

The effect size of the locus further increases in most severe patients

-

•

The risk haplotype likely influences the expression of LZTFL1 and CCR9

Respiratory medicine; Public health; Virology; Genomics

Introduction

Italy was among the first countries outside of Asia to report cases of infections with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).1 In the province of Bergamo, the first official case was reported on 23 February, 2020 in Nembro, a small village with ∼11,000 inhabitants, which in March 2020 recorded an 850 percent increase in the number of deaths.2 Soon, Nembro, nearby towns, and the entire province, became known to the world as the pandemic’s epicenter. On 29 November, 2020, the New York Times wrote:2 “In mid-February 2020, the northern Italian province of Bergamo became one of the deadliest killing fields for the virus in the Western world […] Hospitals became makeshift morgues and produced parades of coffins and scenes of devastation that became a warning to officials in other Western countries of how the virus could rapidly overwhelm health systems and turn infirmaries into incubators”. Indeed, excess mortality for the whole province of Bergamo in March 2020 was 575%, compared to the previous five years (https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/03/tabella-provinciale-decessi-totali-29122022-2.xlsx). Serological screenings carried out across the province in the spring and summer of 2020 revealed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies in 25–38% of subjects, with a peak of 48% in Nembro and neighboring villages.3

The question of why the SARS-Cov-2 disaster overwhelmed the wealthy province of Bergamo, with its top-level hospitals, remains unanswered. Most likely, the outbreak was of such a size that any health system in Europe would have been overloaded.

COVID-19 outcomes were highly unpredictable and the inter-individual variation of clinical manifestations was high, as it remains in unvaccinated, unprimed individuals. Moreover, many people did not get sick, despite taking care, at home and without a face mask, of close relatives or roommates who were severely ill and who eventually died of COVID-19. Risk factors such as age, being male, various comorbidities like obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases or being immunocompromised4 were identified early during the pandemic,4 but we also saw young, healthy women grow critically ill, and conversely, elderly men with multiple diseases did not develop any symptoms despite significant exposure. The high variability observed in infection outcomes suggested the involvement of host genetics, as was shown by the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) involving two cohorts of patients with COVID-19 and respiratory failure.5

At the same time, research consortia were established worldwide to interrogate the genomes of thousands of people to identify genetic risk factors. The largest of these consortia, the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (HGI), has so far identified, through large-scale meta-analyses of GWAS, 23 loci associated with susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or with becoming gravely ill with COVID-19.6 They reported small to moderate effects, with odds ratios (OR) ranging from 0.9 to 2 for COVID-19 severity and from 0.7 to 1.2 for infection susceptibility, similarly to other studies.5,7,8,9,10,11,12

These data suggest that many genetic factors could play a role in the response to SARS-CoV-2. To make things more challenging, sex, age, concomitant diseases, differences in ancestry, and in people’s behavior, as well as uneven exposure to the virus among the studied populations, can strongly impact the interpretation of the genetic data. The noise has grown as the pandemic has evolved, since factors like vaccinations, boosters and prior infections, as well as the emergence of more and more mutated strains, impact how individuals react to the virus.

The aim of this study was to perform a case-control GWAS based on the known SARS-CoV-2 infection status of all participants, and reduced confounding factors. To this end, we designed the ORIGIN (NCT04799834) project, which involved the voluntary participation of the population in the province of Bergamo following the first wave of the pandemic. Recruited subjects were matched by age, sex and risk factors. The restricted geographical recruitment area minimized population stratification and differences in human behavior, including social, economic and cultural interactions, and in the environment, such as weather, temperature and pollution. Moreover, the exposure to the virus was high and rather homogeneous and the observation period antedates the emergence of the first SARS-CoV-2 variant (i.e., alpha) and the introduction of vaccines.

Results

Questionnaire

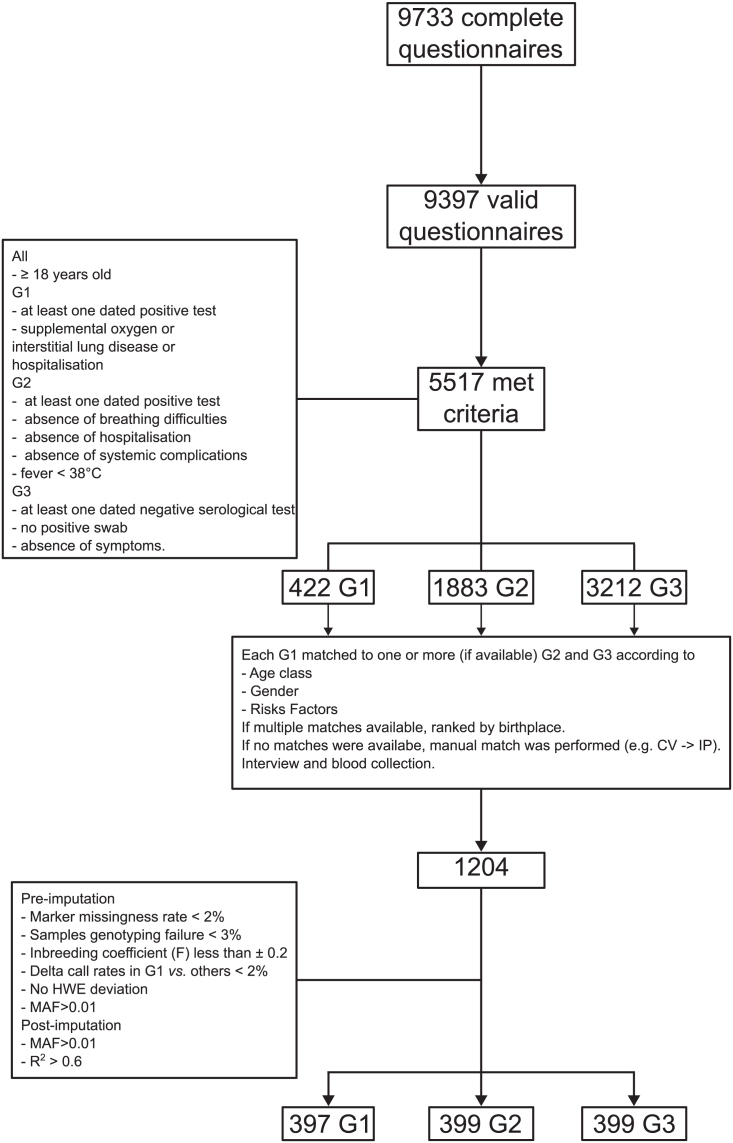

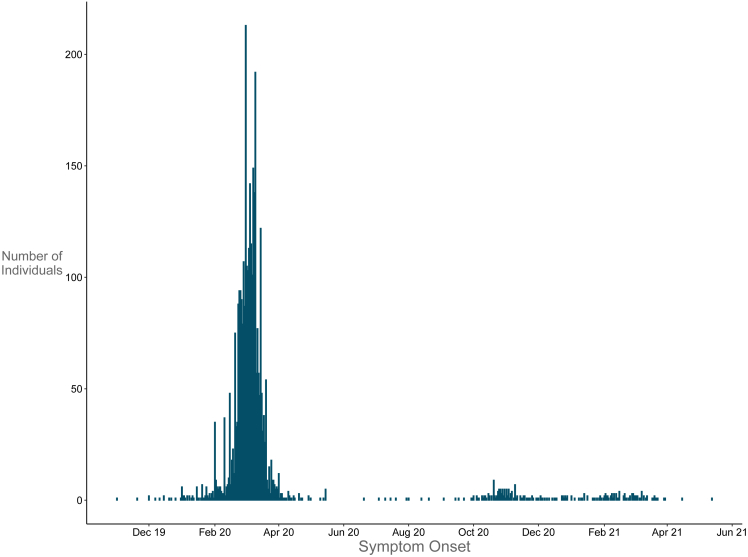

There were 9,733 completed questionnaires at the end of recruitment (Figure 1). After we removed duplicates and questionnaires without a valid birth date, there were 9,397 participants left. 63% of the respondent were female and the average age at completion was 53 years for males and 49 years for females. About 49% reported having had COVID-19-related symptoms. When we considered only the participants with at least one SARS-CoV-2-positive tests and COVID-19-related symptoms (n = 3413), in the vast majority of cases the onset of symptoms occurred earlier than May 2020 (n = 3161, 92%, Figure 2) and 11 participants declared that they had already experienced symptoms in November-December 2019.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and analysis work-flow

Figure 2.

Symptoms onset

Declared symptoms onset of the participants to the questionnaire who reported at least one SARS-Cov2 positive tests and COVID-19 related symptoms with the date of onset or of hospital admission (n = 3413).

Among all those who completed the questionnaire, 5517 were eligible to enroll in the study: 422 had developed severe COVID-19 and were assigned to G1, 1883 were infected with mild or no symptoms (G2) and 3212 did not get SARS-CoV-2 infection (G3) (Figure 1). All G1 cases were included and in order to minimize potential confounding factors, subjects in G2 and G3 were matched against subjects in G1. Details of criteria for group assignment and for matching are provided in STAR Methods section online.

Study cohort: Population stratification and clinical characteristics

The characteristics of the 1195 subjects (G1, n = 397, G2 = 399 and G3 = 399) who were finally selected for the ORIGIN study and whose samples passed the QC are reported in Table 1, and Figures S1–S3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the ORIGIN samples that passed the genotyping quality checks

| Group | G1 | G2 | G3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 397 | 399 | 399 | ||

| Male | 281 | 274 | 282 | Χ22 = 0.54,p = 0.76 | |

| Age (years, mean ± sd) | 60.94 (11.35) | 60.36 (11.15) | 58.86 (11.11) | F2,1192 = 3.7, p = 0.025 | |

| Age class | 18–39 | 16 | 16 | 16 | Χ210 = 7.73,p = 0.65 |

| 40–49 | 40 | 51 | 40 | ||

| 50–59 | 132 | 144 | 136 | ||

| 60–69 | 119 | 122 | 116 | ||

| 70–79 | 75 | 57 | 78 | ||

| 80–99 | 15 | 9 | 13 | ||

| Risk factors | CV | 63 | 38 | 56 | Χ28 = 20.38,p = 0.009 |

| DB | 39 | 22 | 23 | ||

| IP | 106 | 132 | 101 | ||

| none | 140 | 159 | 166 | ||

| SOV | 49 | 48 | 53 | ||

| CV + IP | 169 | 170 | 157 | Χ26 = 9.76,p = 0.14a | |

| N risk factors | 0 | 140 | 159 | 166 | Χ26 = 19.12,p = 0.004 |

| 1 | 146 | 160 | 157 | ||

| 2 | 78 | 68 | 59 | ||

| 3 | 27 | 12 | 15 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Contact with symptomatic individuals or Sars-Cov2+ | yes | 230 | 254 | 199 | Χ22 = 20.38,p = 3.7e-5 |

| no | 133 | 144 | 200 | ||

| missing | 34 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Smoking | yes | 11 | 42 | 64 | Χ22 = 3.32,p = 0.19b |

| no | 246 | 270 | 246 | ||

| past | 131 | 87 | 89 | ||

| missing | 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Birthplace | Bergamo | 309 | 349 | 336 | Χ26 = 21.43,p = 0.002 |

| Lombardy | 34 | 22 | 25 | ||

| Italy | 42 | 22 | 37 | ||

| other | 12 | 6 | 1 |

The last column contains the chi-squared test (Χ2n, with n degree of freedom) and the ANOVA F-test (Fn1,n2, with n1 numerator and n2 denominator degree of freedom respectively) with their respective p values. CV, cardiovascular; DB, diabetes; IP, Hypertension; SOV, overweight.

CV and IP merged.

past and current smokers merged.

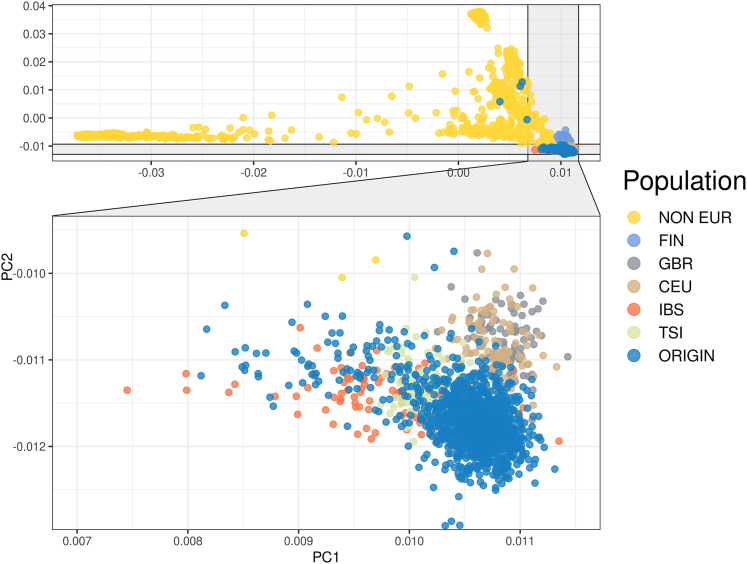

More than 75% of the participants were born in the province of Bergamo (Figure S1). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that all but four individuals clustered among other European populations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Population stratification

Principal Component Analysis of the merged callset of the ORIGIN cohort and the 1000 genome populations. ORIGIN, ORIGIN cohort. CEU, Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry. GBR, British in England and Scotland. FIN, Finnish in Finland. IBS, Iberian populations in Spain. TSI, Toscani in Italy. NON EUR, other, non-European, 1000 genomes populations. The 4 ORIGIN non-European participants are all from South America.

As per matching criteria, the three groups were homogeneous for sex, age distribution, and for concomitant diseases (Figures S2 and S3; Table 1) although the G1 group contained more individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases compared to G2 (Table 1).

The proportion of past and current smokers ranged from 32% in G2 to 38% in G3 (Table 1) and did not differ between groups, contrary to previous studies, which had indicated that smoking could positively or negatively impact SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19.13

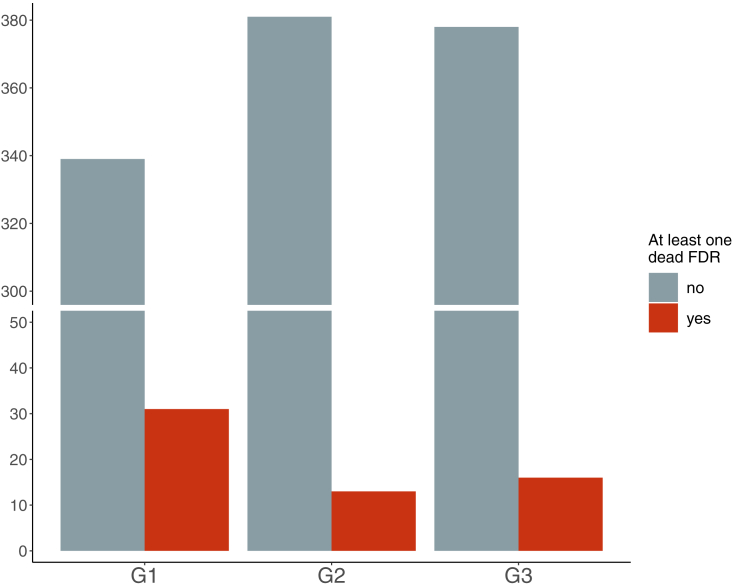

On average, G1 and G2 had more positive/symptomatic contacts than G3 (Table 1). G1 patients reported more frequently that they had first-degree relatives (parents and full-sibs, p = 0.009) who had died of COVID-19 than did participants in G2 and G3 (Figure 4). This result supports the hypothesis that there is a genetic contribution to COVID-19 severity.

Figure 4.

Dead first-degree relatives

Number of subjects reporting at least one first degree relative that died after SARS-Cov2 infection across the three group. FDR, first degree relative.

During SARS-Cov-2 infection all G1 cases had radiology-confirmed pneumonia and/or dyspnea (Table 2). Fever was present in almost all G1 participants and in only 38% of G2 patients. In line with this, cough, headache, myalgia and/or bone pain and gastrointestinal symptoms were observed more frequently in G1 than in G2 patients. Fever, dysgeusia, and parosmia were the most frequent symptoms in G2. One hundred and thirty-five G2 patients were asymptomatic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Symptoms and complications in G1 and G2 patients

| Symptoms | G1 | G2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 pneumonia | 388 | 0 | |

| Dyspnea | 338 | 4 | |

| Fever | 369 | 152 | Χ21 = 262,p < 2.2e-06 |

| Myalgia/bone pain | 259 | 95 | Χ21 = 136.64,p < 2.2e-06 |

| Cough | 254 | 88 | Χ21 = 141,p < 2.2e-06 |

| Dysgeusia | 190 | 125 | Χ21 = 22.05,p = 2.6e-06 |

| Parosmia | 164 | 124 | Χ21 = 8.58,p = 0.003 |

| Headache | 156 | 60 | Χ21 = 58,p < 2.2e-06 |

| Diarrhea | 122 | 38 | Χ21 = 54.41,p < 2.2e-06 |

| Runny nose | 101 | 57 | Χ21 = 14.87,p=0.0001 |

| Gastroenteritis/abdominal pain | 105 | 17 | Χ21 = 73.8,p < 2.2e-06 |

| Throat pain | 63 | 32 | Χ21 = 10.92,p=0.0009 |

| Conjunctivitis | 54 | 32 | Χ21 = 5.87,p=0.015 |

| Complications | G1 | G2 | |

| Fatigue | 347 | 137 | |

| Exertional dyspnea | 150 | 1 | |

| CNS-general | 68 | 4 | |

| CNS-cognitive | 68 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-arrhythmias | 37 | 1 | |

| CNS-psychiatric | 31 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-blood pressure | 24 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 23 | 0 | |

| Respiratory-ARDS | 22 | 0 | |

| Thromboembolism-other | 20 | 0 | |

| Kidney-ARI | 19 | 0 | |

| Skin-alopecia | 18 | 0 | |

| PNs-sensory | 18 | 0 | |

| Respiratory-pneumothorax | 16 | 0 | |

| PNs-motor | 8 | 0 | |

| Skin-erythema | 8 | 0 | |

| Endocrine-thyroid | 5 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-pericarditis | 5 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-arrest | 3 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-AMI | 3 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-phlebitis | 3 | 0 | |

| Endocrin-new T2DM | 2 | 0 | |

| Skin-psoriasis | 1 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular-heart failure | 1 | 0 | |

| Kidney-NS | 1 | 0 |

The last column contains the chi-squared test (Χ2n, with n degree of freedom); the statistical tests were performed on the variables that were not directly used for the case-control matching procedure. CNS, central nervous system (CNS) related symptoms; Cardiovascular, cardiovascular disorders; Respiratory, respiratory system disorders; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; Thromboembolism-other, non-pulmonary thromboembolic events; Kidney, renal disorders; ARI, acute renal insufficiency; Skin, skin disorders; PNs, peripheral neuropathy predominantly sensory or motor; Endocrine, endocrine disorders; Thyroid; thyroid dysfunction; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; new T2DM, new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus; NS, nephrotic syndrome.

In G1, there were several acute complications that affected the respiratory system but also other systems, most commonly the central and peripheral nervous system, and the cardiovascular system (Table 2).

GWAS results

Severity

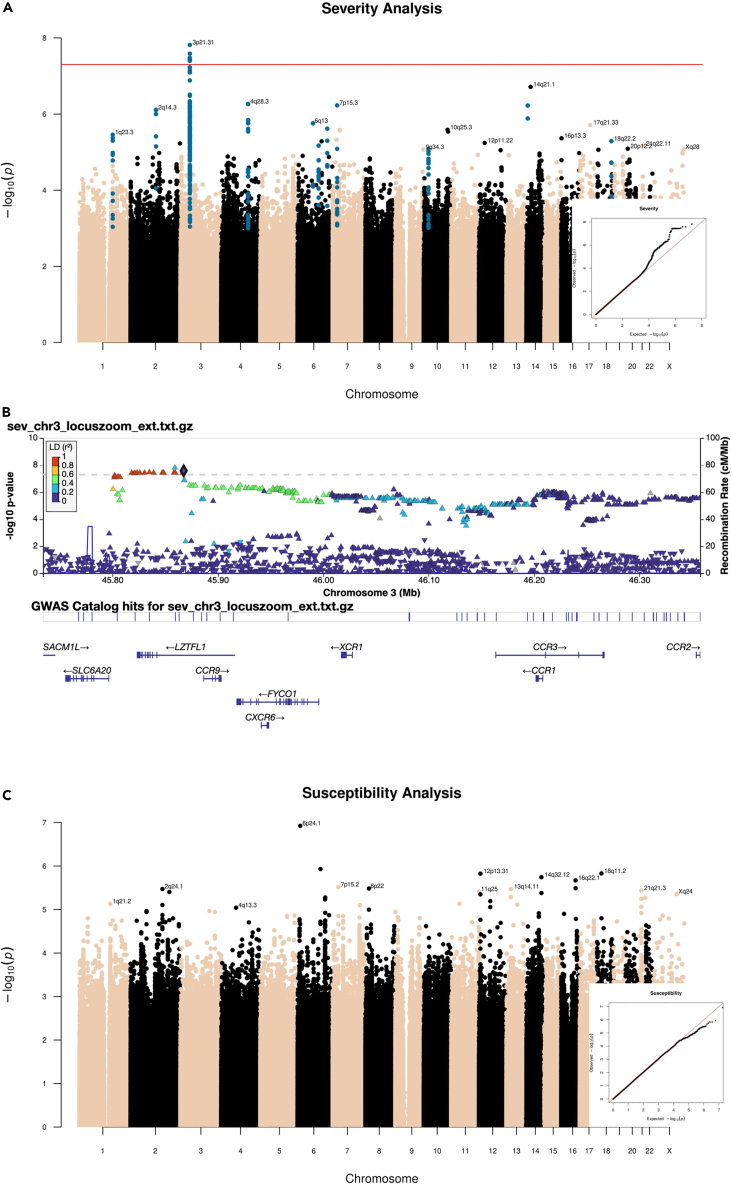

In the severity analysis we included 397 cases (G1) and 798 controls (G2+G3). Only one peak, at locus 3p21.31, was genome-wide significant (Figure 5A, P < 5x10−8). The quantile-quantile (QQ) plot is shown in Figure 5A – the genomic inflation factor was 1.018. A secondary GWAS restricted to G1 vs. G2 confirmed the association of this locus with disease severity (Table S1).

Figure 5.

GWAS results

(A) Manhattan plot and q-q plot (right bottom) of the Severity analysis of the ORIGIN cohort. The horizontal red line is drawn at the genome-wide significance threshold (P=5e-08).

(B) Locus plot of the significant peak on chromosome 3 in the ORIGIN Severity analysis. Markers are colored according to their linkage disequilibrium (LD, r2) with the lead variant. Bottom, gene annotations for the region.

(C) Manhattan plot and QQ plots with results of GWAS susceptibility analysis. The QQ plot shows a slight deflection (genomic inflation factor = 1.012.

The top markers, all in high linkage disequilibrium, included the core haplotype that has been inherited from Neanderthals and was described by Zeberg and Paabo14 (Table S1).

Several genes map to this region (Figure 5B), including CCR9, CXCR6 and XCR1, which encode chemokine receptors.

The conditional analysis showed that only one single signal was present at locus 3p21.31 in the ORIGIN cohort (Figure S4). The lead variant falls in an intronic region of LZTFL1, which encodes a protein that has been shown to suppress lung tumorigenesis by maintaining the differentiation of lung epithelial cells and to regulate ciliogenesis in airway epithelium.15

This locus contains by far the strongest association with COVID-19 severity and respiratory failure across published GWAS.6,10 The lead variant falls within the top 20 markers from the B2 severity analysis (hospitalized COVID-19 patients vs. general population, Table S2) of the COVID-19-HGI6 and has an estimated OR (2.36) that is larger in magnitude than in the B2 analysis of COVID-19-HGI (1.51, Table S1).

As we expected genetic susceptibility to play a stronger role in younger individuals, we performed a logistic regression on disease severity to test the interaction between age and the lead variant. In G1, the prevalence of the risk C allele was slightly higher in younger than in older patients (Figure S5). However, the interaction between the lead variant and age was not significant (p = 0.3). The prevalence of the risk allele did not differ between sexes (Figure S6).

Susceptibility

In the susceptibility analysis, which included 796 cases overall (G1+G2) and 399 controls (G3), none of the markers reached genome-wide significance (Figure 5C).

Comparison with COVID-19-HGI results

The recent update of the COVID-19-HGI6 reported 23 genome-wide significant loci associated with either disease severity (B2, COVID-19 hospitalized vs. population, n = 16) or infection susceptibility (C2, SARS-CoV-2 reported infection vs. population, n = 7). For each of the COVID-19-HGI lead variants, the corresponding ORIGIN allele frequencies were extracted to calculate the naive (i.e., simple allelic test) post-hoc power. The only variant with a reasonably acceptable power was rs35508621, which belongs to the 3p21.31 locus (Table S2). This was in line with our expectation of having the power to detect moderate to high effect sizes (i.e., OR≥2) for moderate to high-frequency alleles.

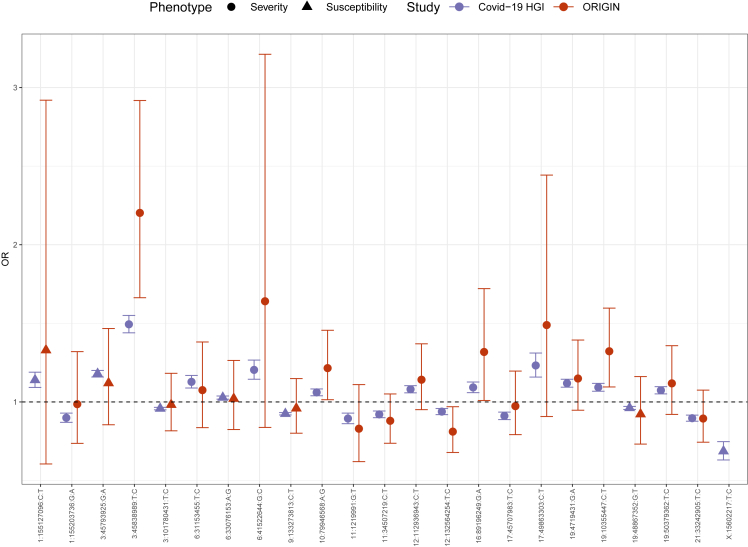

Figure 6 shows the estimated ORs with the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the 23 published lead variants, for the ORIGIN and the COVID-19-HGI datasets. The effect sizes of the ORIGIN studies are generally comparable or even larger in magnitude than those of the COVID-19-HGI (Figures 6 and S7), however the CIs are much larger. Notably, the estimated OR of the 3p21.31 locus was higher at 95% CIs in the ORIGIN cohort. The allele frequencies (AF) of the lead variants of the risk haplotype in the G2 and G3 groups were comparable to those of gnomAD non-Finnish Europeans (NFE),16 suggesting that this finding is not attributable to enrichment of the risk haplotype in Bergamo.

Figure 6.

Comparison with COVID-19-HGI lead variants

Lead variants for severity (circles) and susceptibility (triangles) reported by COVID-19-HGI. Each point represents the odds ratio (with 95% confidence intervals) from the COVID -19 HGI (purple) or the ORIGIN (dark red) studies, respectively. The last marker (X:15602217:T:C) was not present in the final ORIGIN dataset.

Other suggestive loci

We identified 17 loci that reached a suggestive P < 1x10−5 (ten in the severity analysis and seven in the susceptibility analysis, Table 3), which have not been previously reported, to the best of our knowledge.

Table 3.

Other loci

| cytoBand | Gene | Function | ORIGIN analysis | ORIGIN OR | ORIGIN p value | ORIGIN AF case | ORIGIN AF ctrl | N p < 1e-5 | Clumped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1q23.3 | NOS1AP | intronic | Severity | 1.734 | 3.49E-06 | 0.220 | 0.143 | 3 | 11 |

| 2q14.3 | LINC01826; LOC107985820 | intergenic | Severity | 12.768 | 7.79E-07 | 0.024 | 0.003 | 7 | 7 |

| 2q24.1 | KCNJ3 | intronic | Susceptibility | 0.671 | 3.38E-06 | 0.486 | 0.586 | 2 | 27 |

| 4q28.3 | LINC02479; SNHG27 | intergenic | Severity | 0.555 | 5.44E-07 | 0.766 | 0.841 | 14 | 126 |

| 6q13 | LOC101928516; COL12A1 | intergenic | Severity | 11.305 | 1.75E-06 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 4 | 5 |

| 6q16.3 | GRIK2; NONE | intergenic | Severity | 6.276 | 6.74E-06 | 0.026 | 0.006 | 4 | 39 |

| 6q24.2 | UTRN | intronic | Severity | 2.643 | 2.41E-06 | 0.079 | 0.034 | 2 | 6 |

| 7p15.3 | DNAH11 | intronic | Severity | 2.781 | 5.90E-07 | 0.088 | 0.038 | 2 | 20 |

| 10p12.2 | MSRB2; PTF1A | intergenic | Severity | 0.462 | 8.48E-06 | 0.042 | 0.091 | 3 | 66 |

| 12p13.31 | PEX5; ACSM4 | intergenic | Susceptibility | 0.500 | 1.50E-06 | 0.074 | 0.138 | 3 | 37 |

| 12q13.2 | MUCL1; TESPA1 | intergenic | Susceptibility | 0.268 | 6.42E-06 | 0.014 | 0.043 | 2 | 4 |

| 13q14.11 | LINC00548; LINC00598 | intergenic | Susceptibility | 1.558 | 3.40E-06 | 0.356 | 0.263 | 2 | 8 |

| 14q12 | STXBP6; NOVA1 | intergenic | Severity | 7.363 | 5.97E-07 | 0.029 | 0.005 | 2 | 1 |

| 14q32.12 | RIN3 | intronic | Susceptibility | 0.331 | 1.81E-06 | 0.024 | 0.064 | 2 | 1 |

| 16q22.1 | TERF2; CYB5B | intergenic | Susceptibility | 0.256 | 2.14E-06 | 0.011 | 0.044 | 2 | 2 |

| 18q22.2 | RTTN; SOCS6 | intergenic | Severity | 2.779 | 5.13E-06 | 0.068 | 0.031 | 3 | 10 |

| 21q21.3 | APP; CYYR1-AS1 | intergenic | Susceptibility | 0.621 | 3.67E-06 | 0.204 | 0.288 | 6 | 78 |

Loci for which at least two markers reached a p value<1x10−5.

Among these, the markers at locus 2q14.3 might be worth further investigation. There were seven markers that exhibited a P < 1x10−5 in the severity analysis (lead variant rs138614720 with p = 7.79x10−7, Table 3). These variants fall in a region upstream of CNTNAP5, whose expression was upregulated in whole blood of COVID-19 patients vs. healthy controls.17 CNTNAP5 encodes the contactin-associated protein family member 5 that may play a role in the correct development and functioning of the nervous system and be involved in cell adhesion and intercellular communication. It is well expressed in the central nervous system but also in other organs, and in blood lymphocytes. A suggestive association with COVID-19 mortality has been reported for variants that are intronic and downstream to CNTNAP5.18

Post-GWAS analyses

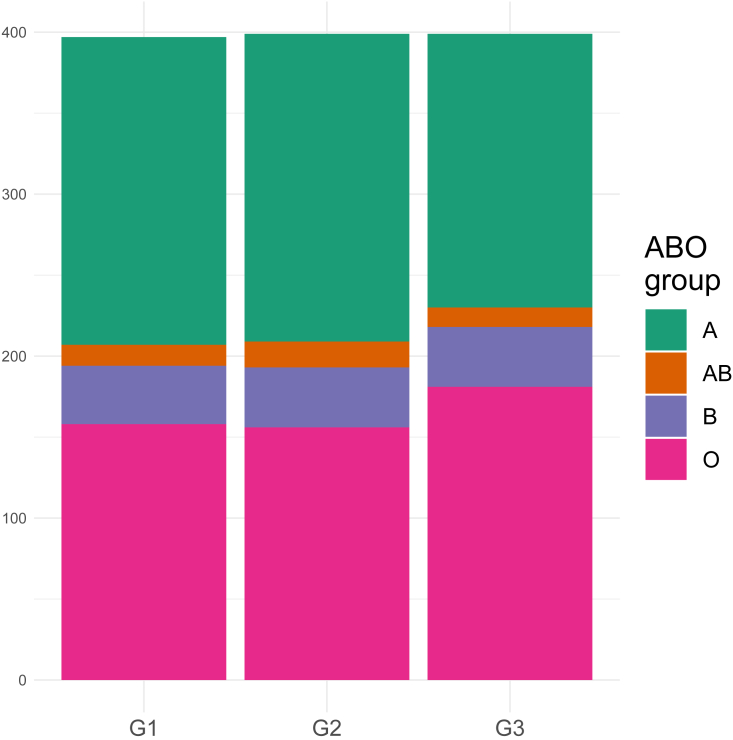

ABO blood group

Previous studies revealed a significant association of the ABO locus with COVID-19 susceptibility.5,11,18 The blood group in the ORIGIN cohort was typed by using three variants, as described by Ellinghaus et al.5 In line with previous studies, we observed an increased frequency of blood group O in uninfected G3 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The distribution of the ABO blood groups among groups

HLA

A few HLA alleles have been associated with either susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection or with COVID-19 severity.19

None of the 120 HLA-tested alleles was significant after correction for multiple tests in the ORIGIN cohort (Tables 4 and 5). The most relevant was DQB1∗03:01 with a nominal P of 0.004 in the severity analysis (Table 4).

Table 5.

The first top 20 HLA alleles of the susceptibility analysis

| Allele | MissingRate | OR | SE | p value | AF case | AF ctrl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C∗12:03 | 0.01506 | 1.454 | 1.16 | 0.0128 | 0.1093 | 0.07644 |

| B∗49:01 | 0.1431 | 0.477 | 1.35 | 0.0136 | 0.01633 | 0.03133 |

| DQB1∗03:02 | 0.06276 | 0.609 | 1.25 | 0.0249 | 0.0358 | 0.05388 |

| DRB1∗04:01 | 0.18159 | 0.488 | 1.38 | 0.027 | 0.01319 | 0.02632 |

| C∗16:02 | 0.01506 | 0.393 | 1.55 | 0.0318 | 0.00691 | 0.01629 |

| B∗18:01 | 0.1431 | 1.415 | 1.18 | 0.0358 | 0.08354 | 0.0614 |

| DPB1∗05:01 | 0.1364 | 2.392 | 1.52 | 0.0375 | 0.01382 | 0.00501 |

| DPB1∗14:01 | 0.1364 | 2.016 | 1.44 | 0.053 | 0.01696 | 0.00752 |

| DRB5∗99:01 | 0.00753 | 0.758 | 1.16 | 0.0595 | 0.88756 | 0.91103 |

| B∗35:02 | 0.1431 | 0.557 | 1.39 | 0.0737 | 0.01445 | 0.02506 |

| A∗31:01 | 0.03347 | 0.612 | 1.33 | 0.0839 | 0.02198 | 0.03258 |

| DRB5∗02:02 | 0.00753 | 1.449 | 1.24 | 0.0896 | 0.04774 | 0.03383 |

| DRB1∗04:04 | 0.18159 | 0.458 | 1.59 | 0.0902 | 0.00691 | 0.01378 |

| DRB1∗16:01 | 0.18159 | 1.402 | 1.24 | 0.1108 | 0.04962 | 0.03634 |

| DRB4∗01:03 | 0.041 | 0.811 | 1.15 | 0.1232 | 0.11432 | 0.13409 |

| C∗05:01 | 0.01506 | 0.746 | 1.21 | 0.1239 | 0.04899 | 0.06516 |

| DRB4∗99:01 | 0.041 | 1.175 | 1.12 | 0.1579 | 0.81847 | 0.79323 |

| DPB1∗19:01 | 0.1364 | 0.534 | 1.56 | 0.1597 | 0.00754 | 0.01378 |

| C∗16:01 | 0.01506 | 0.703 | 1.29 | 0.1633 | 0.02827 | 0.04261 |

| B∗35:03 | 0.1431 | 1.471 | 1.32 | 0.1634 | 0.02952 | 0.02005 |

Table 6.

Odds ratios and clinical severity

| SNP | vcf | G1 AF | ctrl AF | OR | G1-ICU AF | ICU ctrl AF | ICU OR | G1-INT AF | INT ctrl AF | INT OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs76374459 | 3:45859142:G:C | 0.141 | 0.067 | 2.355 | 0.176 | 0.083 | 2.907 | 0.182 | 0.086 | 3.078 |

| rs35652899 | 3:45867022:C:G | 0.156 | 0.078 | 2.220 | 0.190 | 0.095 | 2.644 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.510 |

| rs35044562 | 3:45867532:A:G | 0.156 | 0.078 | 2.220 | 0.190 | 0.095 | 2.644 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.510 |

| rs11385942 | 3:45834967:G:GA | 0.156 | 0.078 | 2.204 | 0.186 | 0.096 | 2.515 | 0.189 | 0.099 | 2.530 |

| rs17713054 | 3:45818159:G:A | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs10490770 | 3:45823240:T:C | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs35624553 | 3:45825948:A:G | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs67959919 | 3:45830416:G:A | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs35508621 | 3:45838989:T:C | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs34288077 | 3:45847198:A:G | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs35081325 | 3:45848429:A:T | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs35731912 | 3:45848457:C:T | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs34326463 | 3:45858159:A:G | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs73064425 | 3:45859597:C:T | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs13081482 | 3:45866624:A:T | 0.155 | 0.078 | 2.203 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.532 | 0.189 | 0.098 | 2.543 |

| rs13078854 | 3:45820440:G:A | 0.154 | 0.078 | 2.198 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.568 | 0.189 | 0.097 | 2.580 |

| rs71325088 | 3:45821460:T:C | 0.154 | 0.078 | 2.198 | 0.186 | 0.095 | 2.568 | 0.189 | 0.097 | 2.580 |

Markers significant at p < 2.5e-8 in the ORIGIN severity analysis compared to the analysis of intensive care unit (ICU) patients and to those who required mechanical ventilation (INT). G1-ICU, G1 in intensive care units; ICU ctrl, all but G1-ICU; G1-INT, G1 that required mechanical ventilation; G1-INT, all but G1-INT; OR, odds ratio.

Correlation of the 3p21.31 locus with clinical severity in COVID-19 patients

One hundred and five out of 397 G1 patients were admitted to intensive care units (G1-ICU) and 74 were intubated (G1-INT). The AF of the lead variant of the severity analysis increased, moving from the whole G1 to the G1-ICU subgroup and finally to the G1-INT subgroup. The OR vs. the controls (G2+G3 for G1; G2+G3+G1 no ICU for G1-ICU; and G2+G3+G1 no INT for G1-INT) also increased to a maximum of 3 in G1-INT cases (Table 6), confirming the association of this locus with COVID-19 severity.

Table 4.

The first top 20 HLA alleles of the severity analysis

| Allele | MissingRate | OR | SE | p value | AF case | AF ctrl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DQB1∗03:01 | 0.06276 | 0.751 | 1.11 | 0.00444 | 0.2796 | 0.34148 |

| B∗49:01 | 0.1431 | 0.478 | 1.35 | 0.01441 | 0.01259 | 0.02569 |

| DQA1∗05:01 | 0.08117 | 0.784 | 1.11 | 0.01512 | 0.3199 | 0.36717 |

| DQB1∗05:03 | 0.06276 | 1.562 | 1.22 | 0.02334 | 0.07053 | 0.04762 |

| DPB1∗05:01 | 0.1364 | 2.683 | 1.55 | 0.02446 | 0.01637 | 0.00815 |

| A∗11:01 | 0.03347 | 1.513 | 1.21 | 0.02759 | 0.07683 | 0.05702 |

| DQA1∗01:01 | 0.08117 | 1.313 | 1.13 | 0.02919 | 0.17506 | 0.14411 |

| DRB5∗02:02 | 0.00753 | 1.615 | 1.25 | 0.03222 | 0.05416 | 0.03759 |

| A∗25:01 | 0.03347 | 1.758 | 1.32 | 0.0412 | 0.03652 | 0.02506 |

| DRB1∗14:01 | 0.18159 | 1.567 | 1.25 | 0.0455 | 0.05542 | 0.03446 |

| DPB1∗09:01 | 0.1364 | 2.171 | 1.51 | 0.06189 | 0.01763 | 0.00815 |

| C∗16:02 | 0.01506 | 0.453 | 1.57 | 0.07743 | 0.00504 | 0.01253 |

| B∗50:01 | 0.1431 | 0.635 | 1.32 | 0.10277 | 0.01889 | 0.02882 |

| B∗55:01 | 0.1431 | 0.523 | 1.49 | 0.10309 | 0.00756 | 0.01629 |

| C∗16:01 | 0.01506 | 0.674 | 1.3 | 0.13266 | 0.02267 | 0.03822 |

| DRB3∗99:01 | 0.02343 | 1.148 | 1.1 | 0.13407 | 0.51133 | 0.48058 |

| DQB1∗05:02 | 0.06276 | 1.359 | 1.23 | 0.13655 | 0.05793 | 0.04637 |

| DPB1∗11:01 | 0.1364 | 1.705 | 1.44 | 0.14701 | 0.02015 | 0.0119 |

| A∗29:02 | 0.03347 | 0.678 | 1.31 | 0.15376 | 0.01889 | 0.03133 |

| DQA1∗04:01 | 0.08117 | 1.412 | 1.27 | 0.15506 | 0.0403 | 0.03258 |

Transcriptome-wide association study analysis (TWAS)

After correction for multiple comparisons, CCR9 (whole blood eQTL) and LZTFL1 (whole blood and lung sQTL: splicing eQTL) were significantly associated with disease severity in the TWAS (Table 7). For both genes, the GTEx v8 MASHR models contained a single marker (rs13081482 for CCR9 and rs35624553 for LZTFL1) that belonged to the association peak at 3p21.31. Both markers were associated with an increase in the expression of their target gene or target exon-exon junction. These genes, together with other neighbor genes, have been reported in similar analyses.9,10

Table 7.

TWAS on severity

| gene id/junction | effect | se | Z score | p value | gene | rsid | varID | ref_allele | eff_allele | tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENSG00000173585.15 | 1.212 | 0.215 | 5.636 | 2.17E-08 | CCR9 | rs13081482 | chr3_45866624_A_T_b38 | A | T | WB eqtl |

| ENSG00000164849.9 | −0.197 | 0.054 | −3.677 | 2.46E-04 | GPR146 | rs113575110 | chr7_1044758_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB eqtl |

| GPR146 | rs4513886 | chr7_1125064_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000204308.7 | 0.680 | 0.191 | 3.551 | 3.99E-04 | RNF5 | rs2269423 | chr6_32177930_A_C_b38 | A | C | WB eqtl |

| RNF5 | rs9267812 | chr6_32160617_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB eqtl | |||||

| RNF5 | rs36022314 | chr6_32177911_TA_T_b38 | TA | T | WB eqtl | |||||

| RNF5 | rs204996 | chr6_32182106_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000171163.15 | 7.140 | 2.019 | 3.536 | 4.21E-04 | ZNF692 | rs12138374 | chr1_248859244_G_T_b38 | G | T | WB eqtl |

| ENSG00000167447.12 | −0.635 | 0.183 | −3.475 | 5.29E-04 | SMG8 | rs493740 | chr17_59199202_G_C_b38 | G | C | WB eqtl |

| SMG8 | rs11655197 | chr17_59209673_G_T_b38 | G | T | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000126858.16 | 0.508 | 0.148 | 3.437 | 6.08E-04 | RHOT1 | rs41291034 | chr17_32084077_G_GC_b38 | G | GC | WB eqtl |

| RHOT1 | rs13342625 | chr17_32142404_C_A_b38 | C | A | WB eqtl | |||||

| RHOT1 | rs376459993 | chr17_32142595_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000188152.12 | 0.290 | 0.085 | 3.396 | 7.07E-04 | NUTM2G | rs148692584 | chr9_96893723_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB eqtl |

| NUTM2G | rs539288237 | chr9_96930253_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000010310.8 | −0.445 | 0.131 | −3.384 | 7.38E-04 | GIPR | rs2302382 | chr19_45669311_C_A_b38 | C | A | WB eqtl |

| GIPR | rs9749225 | chr19_45672187_T_A_b38 | T | A | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000237541.3 | −0.125 | 0.037 | −3.373 | 7.68E-04 | HLA-DQA2 | rs113458306 | chr6_32555506_A_G_b38 | A | G | WB eqtl |

| HLA-DQA2 | rs9271375 | chr6_32619290_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB eqtl | |||||

| HLA-DQA2 | rs9272358 | chr6_32636761_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB eqtl | |||||

| HLA-DQA2 | rs17206350 | chr6_32707290_T_C_b38 | T | C | WB eqtl | |||||

| ENSG00000204852.15 | −0.773 | 0.234 | −3.296 | 1.01E-03 | TCTN1 | rs12813324 | chr12_110588815_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB eqtl |

| intron_3_45826332_45827356 | 189.243 | 33.577 | 5.636 | 2.17E-08 | LZTFL1 | rs35624553 | chr3_45825948_A_G_b38 | A | G | WB sqtl |

| intron_8_27290178_27294080 | −0.462 | 0.118 | −3.931 | 8.95E-05 | TRIM35 | rs12386854 | chr8_27290422_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB sqtl |

| intron_7_1044658_1045337 | 1.205 | 0.316 | 3.818 | 1.42E-04 | GPR146 | chr7_1044291_G_T_b38 | chr7_1044291_G_T_b38 | G | T | WB sqtl |

| intron_7_1044658_1057492 | 1.240 | 0.328 | 3.777 | 1.66E-04 | GPR146 | rs1881123 | chr7_1045070_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB sqtl |

| intron_1_19357563_19378540 | −0.259 | 0.072 | −3.591 | 3.43E-04 | CAPZB | rs6683394 | chr1_19355675_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB sqtl |

| intron_7_1155584_1157656 | 0.155 | 0.044 | 3.546 | 4.06E-04 | ZFAND2A | rs1133116 | chr7_1155579_A_C_b38 | A | C | WB sqtl |

| intron_13_43085838_43107178 | −24690.584 | 6984.490 | −3.535 | 4.23E-04 | DNAJC15 | rs60311912 | chr13_43085908_C_CATT_b38 | C | CATT | WB sqtl |

| intron_7_1153131_1155453 | −1.067 | 0.309 | −3.450 | 5.80E-04 | ZFAND2A | rs1133122 | chr7_1152936_C_A_b38 | C | A | WB sqtl |

| rs6970867 | chr7_1152655_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB sqtl | ||||||

| intron_7_1153224_1155453 | −0.551 | 0.160 | −3.449 | 5.81E-04 | ZFAND2A | rs1133122 | chr7_1152936_C_A_b38 | C | A | WB sqtl |

| intron_17_2362270_2362838 | 0.103 | 0.030 | 3.445 | 5.92E-04 | SGSM2 | rs2429906 | chr17_2361819_C_A_b38 | C | A | WB sqtl |

| rs8067779 | chr17_2362619_G_A_b38 | G | A | WB sqtl | ||||||

| rs2002863 | chr17_2366475_C_T_b38 | C | T | WB sqtl | ||||||

| intron_3_45826332_45827356 | 97.973 | 17.383 | 5.636 | 2.17E-08 | LZTFL1 | rs35624553 | chr3_45825948_A_G_b38 | A | G | Lung sqtl |

| intron_17_2363134_2363465 | 0.176 | 0.044 | 4.023 | 6.11E-05 | SGSM2 | rs2003969 | chr17_2363415_T_C_b38 | T | C | Lung sqtl |

| intron_8_27290178_27294080 | −0.263 | 0.067 | −3.931 | 8.95E-05 | TRIM35 | rs12386854 | chr8_27290422_G_A_b38 | G | A | Lung sqtl |

| intron_8_27289280_27290156 | −0.336 | 0.086 | −3.931 | 8.95E-05 | TRIM35 | rs12386854 | chr8_27290422_G_A_b38 | G | A | Lung sqtl |

| intron_19_10353646_10354042 | −0.386 | 0.100 | −3.858 | 1.21E-04 | TYK2 | rs12720358 | chr19_10353864_C_T_b38 | C | T | Lung sqtl |

| rs280497 | chr19_10354011_A_G_b38 | A | G | Lung sqtl | ||||||

| intron_3_45919065_45919413 | −0.053 | 0.014 | −3.832 | 1.34E-04 | FYCO1 | rs6800954 | chr3_45923467_C_T_b38 | C | T | Lung sqtl |

| rs1994492 | chr3_45919154_T_C_b38 | T | C | Lung sqtl | ||||||

| rs7652331 | chr3_45921260_T_C_b38 | T | C | Lung sqtl | ||||||

| intron_7_1055483_1056104 | −0.088 | 0.023 | −3.796 | 1.55E-04 | GPR146 | rs78861357 | chr7_1055782_C_T_b38 | C | T | Lung sqtl |

| intron_7_1056829_1057492 | 0.252 | 0.066 | 3.796 | 1.55E-04 | GPR146 | rs80031817 | chr7_1057157_T_C_b38 | T | C | Lung sqtl |

| intron_7_1055483_1057492 | 0.219 | 0.058 | 3.796 | 1.55E-04 | GPR146 | rs78861357 | chr7_1055782_C_T_b38 | C | T | Lung sqtl |

| intron_7_1056779_1057492 | 0.224 | 0.059 | 3.796 | 1.55E-04 | GPR146 | rs78143408 | chr7_1057210_G_A_b38 | G | A | Lung sqtl |

Results of TWAS for whole blood and Lung QTLs for Severity in the ORIGIN cohort. There were no genes significant after multiple correction for lungs eQTL (not reported). Only the first gene/junction was significant after multiple correction in all analyses. WB, whole blood; eqtl, expression quantitative trait locis; sqtl, splice quantitative trait loci.

Discussion

We report, with an original matched case-control design, the genetic association of the 3p21.31 locus with severe COVID-19. In the previous large international studies,20 patients who had experienced severe COVID-19 were recruited by several centers, and genetic information about controls was mostly obtained from pre-existing cohorts, including individuals with different ancestries and with unknown SARS-CoV-2 infection status.

The high variability in COVID-19 phenotype likely depends on the interplay between host genetics and non-genetic factors (including age, sex, social, cultural and demographic features, SARS-CoV-2 variants and the environmental exposure to the virus), which might complicate the interpretation of GWAS.

The uniqueness of the ORIGIN approach consists of the following: (1) All participants at the time of enrollment lived in the province of Bergamo, which comprises a relatively small area (2.723 km2, with around 1,100,000 inhabitants) in Lombardy, which was the epicenter of the pandemic in Italy and Europe early in 2020. (2) Over 75% were born in the province of Bergamo and PCA showed that population stratification was not a concern for the analysis. (3) Over 90% of the infections in the ORIGIN cohort occurred during the first wave, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants and before the endorsement of life-saving treatment with steroids and anti-inflammatory drugs,21 and largely in advance of the vaccination era. (4) Cases and controls were matched for the main factors that were reported early on to affect COVID-19 outcomes, including age, sex and concomitant diseases.22,23 Participants were recruited using an online questionnaire, and we collected detailed clinical data and directly verified all self-reported information through personal interviews.

The above features make ORIGIN a cohort with low ancestry heterogeneity that underwent high environmental exposure to the same SARS-CoV-2 variant, and with limited confounding effects from therapeutic and prophylactic treatments and from secondary concomitant conditions that could have impacted COVID-19 severity analysis. Finally, we knew, with a fair degree of certainty, the infection and clinical history of all participants at the time of enrollment.

Compared to the COVID-19 Host Genetic Initiative (HGI), a project that brought together over 100 cohorts from dozens of countries,6 we observed a stronger effect size at the 3p21.31 locus, which further increased in the most severe patients.

Our GWAS could not replicate other loci associated with COVID-19 severity6,24,25 although the effect sizes correlated with those reported by other studies. Nevertheless, our results highlight the impact of the 3p21.31 locus on COVID-19 severity, compared to that of the other loci.

The lead variant at this locus lies in an intron of LZTFL1 and is in linkage with markers spanning a cluster of inflammatory genes that encode chemokine receptors, including CCR9, CXCR6, and XCR1.

LZTFL1 encodes the leucine zipper transcription factor-like protein 1 (LZTFL1) that regulates ciliogenesis and ciliary function,26 and inhibits the signals that lead to epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT).15 LZTFL1 is highly expressed in pulmonary epithelial cells as well as in ciliated human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) and its expression correlates with HBEC differentiation.15 Our TWAS showed that variants at this locus may influence LZTFL1 splicing in the lung and in blood, and is in line with previous studies, which identified LZTFL1 as the target of the risk allele at the 3p21.31 locus. Fink-Baldauf et al.27 hypothesized that patients who carry the risk haplotype have inefficient SARS-CoV-2 clearance due to reduced expression of LZTFL1, which leads to fewer airway ciliated cells. On the other hand, Downes DJ et al.28 hypothesized that a gain-of-function effect of the risk haplotype increases the levels of LZTFL1, which may slow EMT-driven tissue repair following viral infection. Thus, the available results do not clarify whether the causal relation between the risk haplotype and COVID-19 severity is mediated by LZTFL1 expression.

We also found that the risk haplotype contains eQTLs for increased whole blood expression of CCR9, consistently with other studies.9,29,30 CCR9 encodes the C–C chemokine receptor type 9, which plays a key role in regulating T lymphocyte recruitment and promoting inflammation during infections.31 Yao et al.32 found that 6 variants that belong to the risk haplotype overlap with a T cell specific enhancer. They hypothesized that variants in this region could affect the expression of CCR9 and mediate the severity of COVID-19.

Further investigations are required to clarify whether, how and to what degree the COVID-19 severity allele impacts on the levels and/or function of the products of LZTFL1, CCR9 and of the other genes mapping at this locus.

Associations of the ABO locus that determines blood group with COVID-19 have been reported in several studies. However, the results are conflicting regarding whether the ABO locus influences COVID-19 severity, susceptibility to infection, or both.33 We found that the O group was slightly more prevalent in the uninfected G3 group compared to G1 and G2 groups. This would support the hypothesis that the O allele has a protective effect against infection.

We also identified 17 loci suggestive for an association with either COVID-19 severity or susceptibility to infection, which have been not previously reported, to the best of our knowledge. Among them, the one at 2q14.3 is of interest. Here, 7 variants reached a p value suggestive of an association with severity. These variants fall upstream of the CNTNAP5 that encodes the contactin-associated protein family member 5, which is involved in cell adhesion and intercellular communication. CNTNAP5 expression was upregulated in whole blood of COVID19 patients vs. healthy controls.17 Additionally, a suggestive association with COVID-19 mortality has been reported for other variants that are intronic and downstream to CNTNAP5.18 Altogether, the present and published data suggest that variants in the CNTNAP5 locus may have an impact on the risk of developing severe COVID-19.

Conclusions

In summary, the ORIGIN study further highlights the impact of the risk allele at the 3p21.31 locus in COVID-19 severity, which effect size further increased in gravely ill patients, and pinpointed the LZTFL1 and CCR9 as the focus of further research to gain insights into causes of morbidity. We also identified 17 loci not previously reported, suggestive for an association with either COVID-19 severity or susceptibility.

The outbreak in Lombardy was unpredicted and of such a size that it led to a rapid overflow of all health care facilities. It is likely that the virus was circulating in January, or even earlier (Figure 2; 34). In this regard, it is noteworthy that 11 persons who completed the ORIGIN questionnaire stated that they had already experienced COVID-19-related symptoms in November-December of 2019.

Limitations of the study

This study was based on subjects from the restricted area of Bergamo province who underwent an extremely high degree of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 during a short and well-defined period of time, and who volunteered to participate in the study. The design imposed some limitations that should be considered. Due to the voluntary nature of participation, the cohort lacks the extreme phenotype of patients who died of COVID-19. In addition, the study was underpowered to confirm associations with published loci that have a rather low effect size.

Consortia

ORIGIN ORGANIZATION: G. Remuzzi, MD. M. Noris, PhD; N Rubis RN; M. Breno, PhD; S. Gamba, RN; E. Daina MD; A. Benigni, PhD. P. Boccardo, BiolSciD; S. Peracchi, J. Piffari. D. Martinetti, Eng; S. Carminati, Eng.W. Calini; O. Diadei ChemD; G. Gherardi, RN; S. Orisio PhD; N. Rubis RN; A. Villa BiotechD; D. Villa ResNatD. E. Bresin, MD; D.I. Cadè, RN; A. Cannata, Lab Tech; F. Carrara, BiolSciD; P. Carrara, RN; D. Cugini, BiolSciD; D. Curtò, MD; A.A. Diffidenti, RN; S. Ferrari, Lab Tech; S. Gamba, RN; T. Gamba, MD; S. Gioia, RN; C. Guarinoni, RN; A. Imeraj MD; V. Lecchi, RN; A. Parvanova, MD, PhD, DSc; S. Prandini, RN; M. Rigoldi MD; N. Stucchi, M. Montefusco, Lab Tech. M. Alberti, Lab Tech; R. Donadelli, BiolSciD; L. Liguori, BiolSciD; C. Mele, PhD; S. Orisio, PhD; R. Piras, PhD; E. Valoti, PhD. M. Breno, PhD; M. Noris PhD. D. Abbatantuono; L. Generali; B. Greco; G. Masserdotti; E. Lubrina; A. Schieppati MD; Press: AdnKronos, Alto Adige, Araberara, Avvenire, Bergamonews, Bergamo TV, Corriere della Sera Bergamo, D – La Repubblica, Gente, Il Farmacista Online, Il Giornale, Il Giorno, Il Popolo Cattolico, L’Eco di Bergamo, Panorama della Sanità, Prima Bergamo, Quotidiano Sanità, Rai 3 – Presa Diretta, Rai 3 – Quante Storie, Terra nuova, TG1 Medicina, TGR Leonardo, Vita.it.L. Arioli; R. Gervasoni; M. Minali; B. Remonti; S. Yakimchuk.

Administrations: Bergamo (G. Gori, Mayor; C. Sanchez, Capo di Gabinetto and the staff of Oggi Come Stai); Albino (F. Terzi, Mayor); A. Costantini, Director Servizi Sociosanitari Val Seriana (Albino); Alzano Lombardo (C. Bertocchi, Mayor); Aviatico, Casnigo, Cene (E. Moreni, Mayor), Cazzano S. Andrea (S. Spampatti, Mayor), Clusone, Colzate, Cortenuova, Fiorano al Serio, Gandino, Gazzaniga (A. Merici, Deputy Mayor); Ghisalba, Gorle, Leffe, Nembro (C. Cancelli, Mayor); Pedrengo, Peia, Pradalunga, Ranica (M. Vergani, Mayor); Romano di Lombardia (S. Nicoli, Mayor); San Giovanni Bianco, Scanzorosciate, Selvino, Seriate, Torre de Busi, Vertova, Villa di Serio, Zogno.

Educational Institutes: B. Belotti (Bergamo); G. Camozzi (Bergamo); E. De Amicis (Bergamo); E. Donadoni (Bergamo); G. Galli (Bergamo); Imiberg (Bergamo); IPIA C. Pesenti (Bergamo); ISIS G Natta (Bergamo); ITIS Paleocopa (Bergamo); V. Muzio (Bergamo); Santa Lucia (Bergamo); Scuola Materna Suor M.M.A. Pesenti (Alzano Lombardo); E. Talpino (Nembro).

Diocese and Priests: Mons. A. Bellini; Mons. F. Beschi; Bishop (Bergamo); Mons. G Carzaniga; Don M. Cella; Don D. Bravo Chaplain (Hospital Pesenti Fenaroli, Alzano L); Don I. Chiodi, Director (Oratorio San F Neri, Nembro); Don G. Merlini, Parish Priest (Leffe); Parish Priest (Alzano Lombardo); Parish Priest (Gandino); Parish Priest (Gavarno-Nembro); Parish Priest (Bergamo); Don F. Tomaselli; the Priests of Valgandino. Medical doctors: ATS (Bergamo); M.C. Aparicio; E. Bombana, MD Infectious Disease Specialist (ASST-Bergamo Est, Bergamo); F. Carrara Dentist (Alzano Lombardo); F. Di Marco, MD Unit of Pulmonary Medicine, F. Locati, MD General Manager; L. Lorini, MD Intensive Care Unit (ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo), L. Mosconi MD Family doctor (Gandino); R. Munda MD Family doctor (Nembro); M. Pandini, MD Family doctor, G.N. Valerio MD Family doctor, B. Pazzano MD Pediatrician (Nembro); MD Family doctor (Cene), Centro Medico Valseriana (Vertova). Pharmacies: Farmacia Agostini (Fiorano al Serio); Farmacia Ambrogina (Gorle); Farmacia E. Carrara (Casnigo); Farmacia Dr. Castelli (Selvino); Farmacia Centrale (Albino); Farmacia Centrale Pesenti; Farmacia Farmacia dr. Corbelletta (Torre Boldone); Farmacia De Gasperis; Farmacia Farma Salute (Gandino); Farmacia M. Gallerani (Villa di Serio); Farmacia S. Gandossi; Farmacia Giacherio (Ranica); Farmacia Le Torrette; Farmacia Mandelli (Bergamo); Farmacia Nuova Fortini (Seriate); Farmacia Pancheri (Leffe); Farmacia F. Pagnoncelli (Scanzorosciate); Farmacia Rotelli (Cene); Farmacia Rebba (Nembro); Farmacia San Rocco (Vertova); Farmacia M. Strauch (Pradalunga); Farmacia V. Trussardi (Colzate); Farmacia Vall`Alta di Albino P. Dragoni, Farmacia G. Venturini; Farmacia Verzeri; Farmacia Villa di Serio; Farmacia Villaggio Sposi S. Giassi; Farmacia Via Camozzi D. Visigalli (Bergamo).

Associations and Foundations: ACLI (Nembro); Amici della Biblioteca (Nembro); ASD David (Nembro); ASD Atletica Saletti (Nembro); Associazione Nazionale Alpini Gruppo (Nembro); AS Volleymania (Nembro); AVIS provinciale (Bergamo); Centro Italiano Femminile (Nembro); Club Alpino Italiano (Nembro); Distretto delle 5 Terre della Val Gandino (Gandino); Federfarma (Bergamo); Federmanager (Bergamo); Fondazione A.R.M.R. Aiuti Per La Ricerca Sulle Malattie Rare (Bergamo); Gherim (Nembro); Lions Club (Bergamo); Paese Vivo (Nembro); Peia’s Friends (Peia); Redazione di Il Nembro (Nembro); Rotary Club (Bergamo); Progetto Rocco (Bergamo); Seriana Basket (Nembro); Sindacato CGIL (Nembro); Sindacato CISL-FNP (Nembro).

Volunteers: A. Barcella; T. Bergamelli (Nembro); E. Corbani (Bergamo); S. Daminelli (Urgnano); D. Fornoni (Nembro); G. Gherardi; I. Lenzi (Nembro); I giovani dell’Oratorio (Nembro); C. Maffioletti (Pedrengo); D. Melacini and the researchers of Centro Anna Maria Astori Science and Technology Park Kilometro Rosso (Bergamo); M. Morigi; S. Morotti (Nembro); A. Noris (Nembro); M. Passera; L. Perico, A. Pezzotta, A. Piccinelli, A. Russino (Nembro); P. Pulieri and the researchers of Clinical Research Center for Rare Diseases Aldo e Cele Daccò, Ranica, Bergamo; F. Perani (Casnigo); M. Perego (Urgnano); N. Persico and Church service volunteers (Nembro); The shopkeepers (Nembro); V. Trovesi (Library, Nembro); and many others.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Individual level genotype, typed and imputed markers | This study | EGAS00001007310 |

| Variant call sets of the 1000 Genomes project mapped on GRCh38 | Lowy-Gallego et al. | http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/data_collections/1000_genomes_project/release/20190312_biallelic_SNV_and_INDEL/ |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| PLINK 1.9 | Chang et al.47 | https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/ |

| SAIGE | Zhou et al.23,39 | https://github.com/weizhouUMICH/SAIGE |

| MetaXcan | Barbeira et al.41,42 | https://github.com/hakyimlab/MetaXcan |

| GTEx v8 MASHR models | Barbeira et al.41,42 | https://zenodo.org/record/3518299/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Marina Noris (marina.noris@marionegri.it).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and study participant details

Participants

This study reports the results of a matched case-control GWAS conducted on 1195 participants. The recruitment and matching procedure are described in the Method details section. The demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Azienda Socio-Sanitaria Territoriale Papa Giovanni XXIII, and all participants signed the written informed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Method details

Questionnaires data collection

In order to recruit potential candidates for the study, an online, public questionnaire was developed using the Google Forms platform. The questionnaire consisted of various types of questions (multiple choice, open answer, radio button) and was accessible 24 hours a day through a dedicated website.(https://origin.marionegri.it).

Every day, at 6 p.m., data collected over the previous 24 hours were extracted in a compressed CSV format and transferred to an internal Mysql database using automated PHP scripts, with incremental logic. Each new questionnaire was assigned a unique internal ID. The data were backed up daily and removed from Google Forms for security reasons.

The consistency of the data received (by cross-checking the date of birth of parents and children, for example) was verified using PHP scripts developed to manage special characters, prevent the unwanted importing of malicious code and build an outline of the familial relationships between participants.

Additionally, physical copies of the questionnaire were provided to local community centres and to elderly people, thanks to volunteers.

Case-control matching and data collection

Participants were assigned to one of three study groups: severe cases (G1), infected with mild or no symptoms (G2) and non-infected (G3).

Criteria for G1 were all of the following: being 18 or older, having at least one dated positive serologic test or a dated positive swab, having received supplemental oxygen, either at home or in a hospital. Additionally, 31 subjects who did not report the use of oxygen but reported interstitial lung disease or hospitalisation were assigned to G1.

Criteria for G2 were all of the following: being 18 or older, having at least one dated, positive serologic test or one dated positive swab, absence of breathing difficulties, absence of hospitalisation, absence of systemic complications and fever < 38°C.

Criteria for G3 were: being 18 or older, having at least one dated negative serological and no positive swab, and the absence of symptoms (Figure S1).

All G1 cases were included and in order to minimise potential confounding factors, subjects in G2 and G3 were matched against subjects in G1.

Each individual who answered the questionnaire was stratified according to sex, age class and pre-existing risk factors. For each G1 member, one or two (depending on availability) members of G2 and G3, in the same strata, were chosen as a match. Additionally, birthplace was used to rank the preferred match if multiple matches per individual were available.

The following age classes were used: 18-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, and 80-99. Subjects with more than one pre-existing risk factors were classified according to the following rule:

Cardiovascular (CV) > Diabetes (DB) > Hypertension (IP) > Overweight (SOV) > None (none). Birthplaces were grouped into four categories: Bergamo (born in the province of Bergamo), Lombardy (born in the region of Lombardy, but not in the province of Bergamo), Italy (born in Italy, but not in the region of Lombardy) and other (not born in Italy).

Matched participants were discarded if their relatives (i.e., from avuncular to first degree) were among those already chosen and the matching procedure was repeated. Relatives were revealed by an informatics procedure and by building a pedigree to calculate the kinship matrix. If a match was not available, the ‘closest’ match was chosen manually; for example, a few G1 subjects with CV as risk factor were manually matched to IP subjects in the other groups. The matched subjects were contacted by phone and asked to participate in the study. Those who accepted were interviewed by clinicians at the Centro Daccò to verify the correctness of the questionnaires, to collect additional clinical information, and to provide informed consent to participate in the study. EDTA blood samples were collected from all consenting subjects (Figure S1).

Following the interviews with the selected participants, the Web Interactive System for eCRF (WISE) was used to collect and store the data.

WISE is a validated platform developed in-house by the Mario Negri Institute based on the LAMP (Linux-Apache-MySQL-PHP) platform. WISE is used to collect and manage data from clinical studies through e-CRF (electronic case report forms) that constitute the front-end part of the system, with direct interaction with the system users. The system is provided with standard templates that can be customised to fulfil clinical study protocol requirements.

Quantification and statistical analysis

QC and imputation

In total, 1204 samples were genotyped on the Axiom™ Human Genotyping SARS-CoV-2 array (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which contains over 820,000 markers, at the Applied Biosystems Microarray Research Services Laboratory (MRSL, Santa Clara, CA USA).

Samples were genotyped in two batches. One sample failed to produce a scan, while two samples failed QC metrics. After genotyping, there was one sex mismatch (the sample was removed) and 18 samples with unknown probe-intensity-inferred sex. The sex of these samples was double checked with plink --check-sex and their manifest sex was confirmed.

A post-genotyping quality check was carried out separately with plink for the two batches; the following filters were applied: marker missingness rate > 2%, sample genotyping failure rate > 3%, inbreeding coefficient (F) less than +-0.2 and difference in call rates between cases (G1) and controls (the others) greater than 2%. After this first round of QC, the two batches were merged and a second QC was applied with the following filters:

marker missingness rate > 2%, difference in call rates between cases and controls greater than 2%, markers deviating from the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) with a p-value<10-6 in controls and markers with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01.

The TOPMed Imputation Server35,36,37 was used for imputation. Data were prepared according to the suggested pipeline (https://www.well.ox.ac.uk/∼wrayner/tools/). After imputation, variants with a MAF>0.01 and a R2 > 0.6 were retained.

Ancestry and population stratification

Variant call sets of the 1000 Genomes project mapped on GRCh3838 were downloaded and used to create a merged dataset with the ORIGIN samples. Briefly, a list of autosomal LD-pruned markers (obtained with plink using --indeppairwise 50 5 0.2 --chr 1-22) was obtained from the final, quality-checked, merged dataset. Principal component analysis was carried out on the joint callset using plink with options --geno 0.1 --maf 0.05.

Association analysis

After QC and imputation, the final dataset contained 1195 samples and 8,910,189 variants. The selection workflow is shown in Figure S1.

Genome-wide association analysis was performed with SAIGE39 (v1.1.5). The first 10 principal components and age were included as covariates in the model. Two distinct analyses were conducted: Severity (G1 vs. G2 and G3) and Susceptibility (G1 and G2 vs. G3). HLA imputation was done at MRSL using the Axiom HLA Analysis software, which in turn makes use of HLA∗IMP:02.40 Alleles imputed at 4 digits resolution were analysed with SAIGE in the same way as the array markers. Alleles with a posterior probability of less than 0.7 were set to missing, and only alleles with an AF greater than 0.01 and an overall missing rate no higher than 20% (i.e., setting --maxMissing=0.2 in SAIGE) were analysed.

Post-GWAS analyses

Variants were LD-clumped with plink. P1 was set to 1×10-5, P2 to 0.001, clump distance to 1500 Kb and r2 to 0.1. Suggestive loci were defined as those with at least two clumped variants at P<1×10-5.

Conditional analysis of the genome-wide significant peaks was run with SAIGE by including the lead variant of the locus as covariate.

Analyses of the lead variants were carried out by running a logistic regression on disease severity, including the variables of interest and the first 10 PCs as covariates.

Transcriptome-wide association analysis (TWAS) was performed with the metaXcan41 suite using the GTEx v8 MASHR42 models. Individual predicted gene level expression was obtained by running PrediXcan on eQTL and sQTL for lung and whole blood. Association analysis on severity was carried out with PrediXcanAssociation by including age and the first 10 PCs as covariates.

Software

Sample matching and pedigree analysis were carried out with R43 and Julia44 custom scripts. Pedigrees and kinship coefficients were obtained by using the networkR45 and kinship246 R packages. Genotype QC and pre- and post-imputation data processing were carried out using plink1.9,47 bcftools48 and R. Genome-wide association analysis was performed with SAIGE and post-GWAS analyses and graphs were done in R.49,50,51

Additional resources

This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT04799834.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to Kerstin Mierke for editing the manuscript, to Manuela Passera for secretary assistance, and to all those who voluntary contributed to the diffusion and recruitment of ORIGIN participants and to all members of the ORIGIN study organization (see Appendix).

This study would not have been possible without the generous contribution of: Regione Lombardia, ATS Bergamo, Fondazione Cav. Lav. Carlo Pesenti, QuattroR SGR S.p.A., Brembo S.p.A., MEI S.r.l., SMILAB S.r.l., Milano Serravalle - Milano Tangenziali S.p.A., Fondazione Aiuti per la Ricerca sulle Malattie Rare (A.R.M.R.), 3BMeteo S.r.l., GF-ELTI S.r.l., Bluserena S.p.A., Martinelli Ginetto S.p.A., L’Unione per il Sociale Onlus, Parrocchia SS Trinità di Grumello del Monte, Consiglio Notarile Bergamo, Panini S.p.A., C.E. Compagnia Generale Elettronica S.r.l., Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, Barabino Immobiliare S.r.l., Brembomatic Pedrali S.r.l., Milfer S.p.A., ICIS S.p.A., Confartigianato Imprese Bergamo, Studio Marconi ’65, Rotary Club Varese, the creators, partners and participants of La Riffa di Sergio&Giuseppe and Friends.

Author contributions

M.B., M.N., C.M., L.L., N.R., D.M., and G.R. designed the study. M.B., N.R., A.P., D.M., S.G., L.L., C.M., R.P., S.O., E.V., M.A., O.D., E.B., M.R., S.P., N.S., F.C., and E.D. acquired the data. M.B., M.N., and A.P., analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. M.B., M.N., A.P., A.B., and G.R. critically revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: August 16, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107629.

Supplemental information

The top 50 markers of the locus 3p21.31 in the ORIGIN severity analysis (the lead variant is in bold). Case: G1; ctrl: G2+G3; G2 AF: G2 allele frequency; G1 vs. G p-value: p-value of the severity analysis with only G2 controls, HGI B2 p-value and HGI B2 OR refer to the p-value and to the OR of the COVID-19-HGI respectively. GnomAD NFE AF, contains the allele frequency of the marker in the non-Finnish European population of the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD); gnomAD maxAF contains the highest population specific AF of gnomAD, max AF pop contains the name of the population: AMI, Amish, SAS, South Asian, AFR, African/African American.

Lead variants were classified as associated to either disease severity or infection susceptibility in COVID-19 HGI. The power was calculated for a two-sided test for the difference in two proportions. The last row contains a variant that is rare in European population (MAF = 0.0024). In the table, pwr and Hmisc refer to two different analytic methods to estimate power, and 1e5 and 5e8 means an alpha of 1 × 10−5 and 5 × 10−8 respectively.

Data and code availability

-

•

Imputed vcfs have been deposited at EGA and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession number is listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Perico N., Fagiuoli S., Di Marco F., Laghi A., Cosentini R., Rizzi M., Gianatti A., Rambaldi A., Ruggenenti P., La Vecchia C., et al. Bergamo and Covid-19: How the Dark Can Turn to Light. Front. Med. 2021;8:609440. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.609440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz J. The Lost Days that Made Bergamo a Coronavirus Tragedy. N. Y. Times. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meduri G. Terminati Screening Sierologici Nella Bassa Valle Seriana. 2020. https://www.lombardianotizie.online/sierologici-valle-seriana/

- 4.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., Bacon S., Bates C., Morton C.E., Curtis H.J., Mehrkar A., Evans D., Inglesby P., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group. Ellinghaus D., Degenhardt F., Bujanda L., Buti M., Albillos A., Fernández J., Fernández J., Prati D., Baselli G., et al. Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid-19 with Respiratory Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1522–1534. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. Pathak G.A., Karjalainen J., Stevens C., Neale B.M., Daly M., Ganna A., Andrews S.J., Kanai M., Cordioli M., et al. A first update on mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature. 2022;608:E1–E10. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04826-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts G.H.L., Park D.S., Coignet M.V., McCurdy S.R., Knight S.C., Partha R., Rhead B., Zhang M., Berkowitz N., Team A.S., et al. AncestryDNA COVID-19 Host Genetic Study Identifies Three Novel Loci. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.06.20205864. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degenhardt F., Ellinghaus D., Juzenas S., Lerga-Jaso J., Wendorff M., Maya-Miles D., Uellendahl-Werth F., ElAbd H., Rühlemann M.C., Arora J., et al. Detailed stratified GWAS analysis for severe COVID-19 in four European populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022;31:3945–3966. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddac158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kousathanas A., Pairo-Castineira E., Rawlik K., Stuckey A., Odhams C.A., Walker S., Russell C.D., Malinauskas T., Wu Y., Millar J., et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals host factors underlying critical Covid-19. Nature. 2022;607:97–103. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04576-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pairo-Castineira E., Clohisey S., Klaric L., Bretherick A.D., Rawlik K., Pasko D., Walker S., Parkinson N., Fourman M.H., Russell C.D., et al. Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in COVID-19. Nature. 2021;591:92–98. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shelton J.F., Shastri A.J., Ye C., Weldon C.H., Filshtein-Sonmez T., Coker D., Symons A., Esparza-Gordillo J., 23andMe COVID-19 Team. Aslibekyan S., Auton A. Trans-ancestry analysis reveals genetic and nongenetic associations with COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. Nat. Genet. 2021;53:801–808. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pairo-Castineira E., Rawlik K., Bretherick A.D., Qi T., Wu Y., Nassiri I., McConkey G.A., Zechner M., Klaric L., Griffiths F., et al. GWAS and meta-analysis identifies 49 genetic variants underlying critical COVID-19. Nature. 2023;617:764–768. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benowitz N.L., Goniewicz M.L., Halpern-Felsher B., Krishnan-Sarin S., Ling P.M., O’Connor R.J., Pentz M.A., Robertson R.M., Bhatnagar A. Tobacco product use and the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19: current understanding and recommendations for future research. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022;10:900–915. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(22)00182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeberg H., Pääbo S. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. Nature. 2020;587:610–612. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei Q., Chen Z.-H., Wang L., Zhang T., Duan L., Behrens C., Wistuba I.I., Minna J.D., Gao B., Luo J.-H., Liu Z.P. LZTFL1 suppresses lung tumorigenesis by maintaining differentiation of lung epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:2655–2663. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen S., Francioli L.C., Goodrich J.K., Collins R.L., Kanai M., Wang Q., Alföldi J., Watts N.A., Vittal C., Gauthier L.D., et al. A genome-wide mutational constraint map quantified from variation in 76,156 human genomes. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.03.20.485034. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alqutami F., Senok A., Hachim M. COVID-19 Transcriptomic Atlas: A Comprehensive Analysis of COVID-19 Related Transcriptomics Datasets. Front. Genet. 2021;12:755222. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.755222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thibord F., Chan M.V., Chen M.-H., Johnson A.D. A year of COVID-19 GWAS results from the GRASP portal reveals potential genetic risk factors. HGG Adv. 2022;3:100095. doi: 10.1016/j.xhgg.2022.100095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Augusto D.G., Hollenbach J.A. HLA variation and antigen presentation in COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2022;76:102178. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2022.102178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira L.C., Gomes C.E.M., Rodrigues-Neto J.F., Jeronimo S.M.B. Genome-wide association studies of COVID-19: Connecting the dots. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022;106:105379. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatterjee K., Wu C.-P., Bhardwaj A., Siuba M. Steroids in COVID-19: An overview. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings M.J., Baldwin M.R., Abrams D., Jacobson S.D., Meyer B.J., Balough E.M., Aaron J.G., Claassen J., Rabbani L.E., Hastie J., et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreakos E., Abel L., Vinh D.C., Kaja E., Drolet B.A., Zhang Q., O’Farrelly C., Novelli G., Rodríguez-Gallego C., Haerynck F., et al. A global effort to dissect the human genetic basis of resistance to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022;23:159–164. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01030-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brest P., Mograbi B., Hofman P., Milano G. Using Genetics To Dissect SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Trends Genet. 2021;37:203–204. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seo S., Zhang Q., Bugge K., Breslow D.K., Searby C.C., Nachury M.V., Sheffield V.C. A Novel Protein LZTFL1 Regulates Ciliary Trafficking of the BBSome and Smoothened. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink-Baldauf I.M., Stuart W.D., Brewington J.J., Guo M., Maeda Y. CRISPRi links COVID-19 GWAS loci to LZTFL1 and RAVER1. EBioMedicine. 2022;75:103806. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downes D.J., Cross A.R., Hua P., Roberts N., Schwessinger R., Cutler A.J., Munis A.M., Brown J., Mielczarek O., de Andrea C.E., et al. Identification of LZTFL1 as a candidate effector gene at a COVID-19 risk locus. Nat. Genet. 2021;53:1606–1615. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00955-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeberg H. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is associated with protection against HIV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116435119. e2116435119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai Y., Wang J., Jeong H.-H., Chen W., Jia P., Zhao Z. Association of CXCR6 with COVID-19 severity: delineating the host genetic factors in transcriptomic regulation. Hum. Genet. 2021;140:1313–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X., Sun M., Yang Z., Lu C., Wang Q., Wang H., Deng C., Liu Y., Yang Y. The Roles of CCR9/CCL25 in Inflammation and Inflammation-Associated Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:686548. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.686548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao Y., Ye F., Li K., Xu P., Tan W., Feng Q., Rao S. Genome and epigenome editing identify CCR9 and SLC6A20 as target genes at the 3p21.31 locus associated with severe COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2021;6:85. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00519-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts G.H.L., Partha R., Rhead B., Knight S.C., Park D.S., Coignet M.V., Zhang M., Berkowitz N., Turrisini D.A., Gaddis M., et al. Expanded COVID-19 phenotype definitions reveal distinct patterns of genetic association and protective effects. Nat. Genet. 2022;54:374–381. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polver M., Previdi F., Mazzoleni M., Zucchi A. A SIAT3HE model of the COVID-19 pandemic in Bergamo, Italy. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2021;54:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2021.10.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuchsberger C., Abecasis G.R., Hinds D.A. minimac2: faster genotype imputation. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:782–784. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taliun D., Harris D.N., Kessler M.D., Carlson J., Szpiech Z.A., Torres R., Taliun S.A.G., Corvelo A., Gogarten S.M., Kang H.M., et al. Sequencing of 53,831 diverse genomes from the NHLBI TOPMed Program. Nature. 2021;590:290–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S., Forer L., Schönherr S., Sidore C., Locke A.E., Kwong A., Vrieze S.I., Chew E.Y., Levy S., McGue M., et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1284–1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowy-Gallego E., Fairley S., Zheng-Bradley X., Ruffier M., Clarke L., Flicek P., 1000 Genomes Project Consortium Variant calling on the GRCh38 assembly with the data from phase three of the 1000 Genomes Project. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:50. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15126.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou W., Nielsen J.B., Fritsche L.G., Dey R., Gabrielsen M.E., Wolford B.N., LeFaive J., VandeHaar P., Gagliano S.A., Gifford A., et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1335–1341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dilthey A., Leslie S., Moutsianas L., Shen J., Cox C., Nelson M.R., McVean G. Multi-Population Classical HLA Type Imputation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1002877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barbeira A.N., Dickinson S.P., Bonazzola R., Zheng J., Wheeler H.E., Torres J.M., Torstenson E.S., Shah K.P., Garcia T., Edwards T.L., et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1825. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03621-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbeira A.N., Bonazzola R., Gamazon E.R., Liang Y., Park Y., Kim-Hellmuth S., Wang G., Jiang Z., Zhou D., Hormozdiari F., et al. Exploiting the GTEx resources to decipher the mechanisms at GWAS loci. Genome Biol. 2021;22:49. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. https://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bezanson J., Edelman A., Karpinski S., Shah V.B. Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing. SIAM Rev. 2017;59:65–98. doi: 10.1137/141000671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekstrøm C.T. networkR: Network Analysis and Visualization. R package version 0.1.2; 2019. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=networkR [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinnwell J., Therneau T. kinship2: Pedigree Functions. R package version 1.8.5; 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=kinship2 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier L.C., Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M., Lee J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience. 2015;4:7–16. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Danecek P., Bonfield J.K., Liddle J., Marshall J., Ohan V., Pollard M.O., Whitwham A., Keane T., McCarthy S.A., Davies R.M., Li H. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D Turner S. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. J. Open Source Softw. 2018;3:731. doi: 10.21105/joss.00731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu S., Chen M., Feng T., Zhan L., Zhou L., Yu G. Use ggbreak to Effectively Utilize Plotting Space to Deal With Large Datasets and Outliers. Front. Genet. 2021;12:774846. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.774846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dowle M., Srinivasan A. data.table: Extension of `data.frame`. R package version 1.14.2; 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=data.table [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The top 50 markers of the locus 3p21.31 in the ORIGIN severity analysis (the lead variant is in bold). Case: G1; ctrl: G2+G3; G2 AF: G2 allele frequency; G1 vs. G p-value: p-value of the severity analysis with only G2 controls, HGI B2 p-value and HGI B2 OR refer to the p-value and to the OR of the COVID-19-HGI respectively. GnomAD NFE AF, contains the allele frequency of the marker in the non-Finnish European population of the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD); gnomAD maxAF contains the highest population specific AF of gnomAD, max AF pop contains the name of the population: AMI, Amish, SAS, South Asian, AFR, African/African American.

Lead variants were classified as associated to either disease severity or infection susceptibility in COVID-19 HGI. The power was calculated for a two-sided test for the difference in two proportions. The last row contains a variant that is rare in European population (MAF = 0.0024). In the table, pwr and Hmisc refer to two different analytic methods to estimate power, and 1e5 and 5e8 means an alpha of 1 × 10−5 and 5 × 10−8 respectively.

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Imputed vcfs have been deposited at EGA and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession number is listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.